A Man at His F*#king Best

A conversation with editor David Granger (Esquire, GQ, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH THE SUPPORT OF ISSUES MAGAZINE SHOP

We’re 18 episodes into this podcast, and, while several interesting themes have surfaced, one of the more unexpected threads is this: Nearly all magazine-inclined men dream of one day working at Esquire. Some women, too.

Turns out that’s also true for today’s guest, which is a good thing because that’s exactly what David Granger did.

“But all this time I’d been thinking about Esquire, longing for Esquire. It'd been my first magazine as a man, and I'd kept a very close eye on it.”

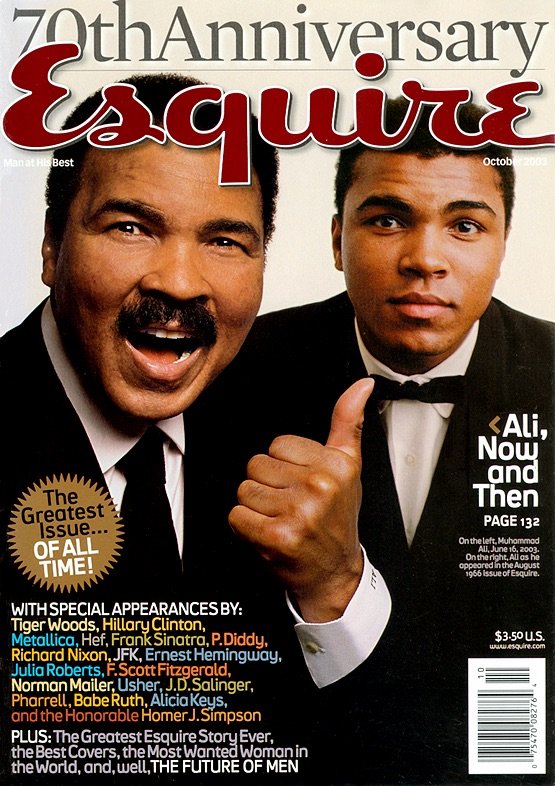

Unless you’re old enough to remember the days of Harold Hayes and George Lois, for all intents and purposes, David Granger IS Esquire. And in his nearly 20 years atop the masthead, the magazine won an astounding 17 ASME National Magazine Awards. It’s been a finalist 72 times. And, in 2020, Granger became a card-carrying member of the ASME Editors Hall of Fame.

When he arrived at Hearst, he took over a magazine that was running on the fumes of past glory. But he couldn’t completely ignore history. Here, he pays homage to his fellow Tennessean, who ran Esquire when Granger first discovered it in college.

“What Phillip Moffitt did was this magical thing that very few magazine editors actually succeed at, which is to show their readers how to make their lives better. And while he's doing that, while he is providing tangible benefit, he also coaxes his readers to stay around for just amazing pieces of storytelling—or amazing photo displays or whatever it is—all the stuff that you do because it's ambitious and because it's art.”

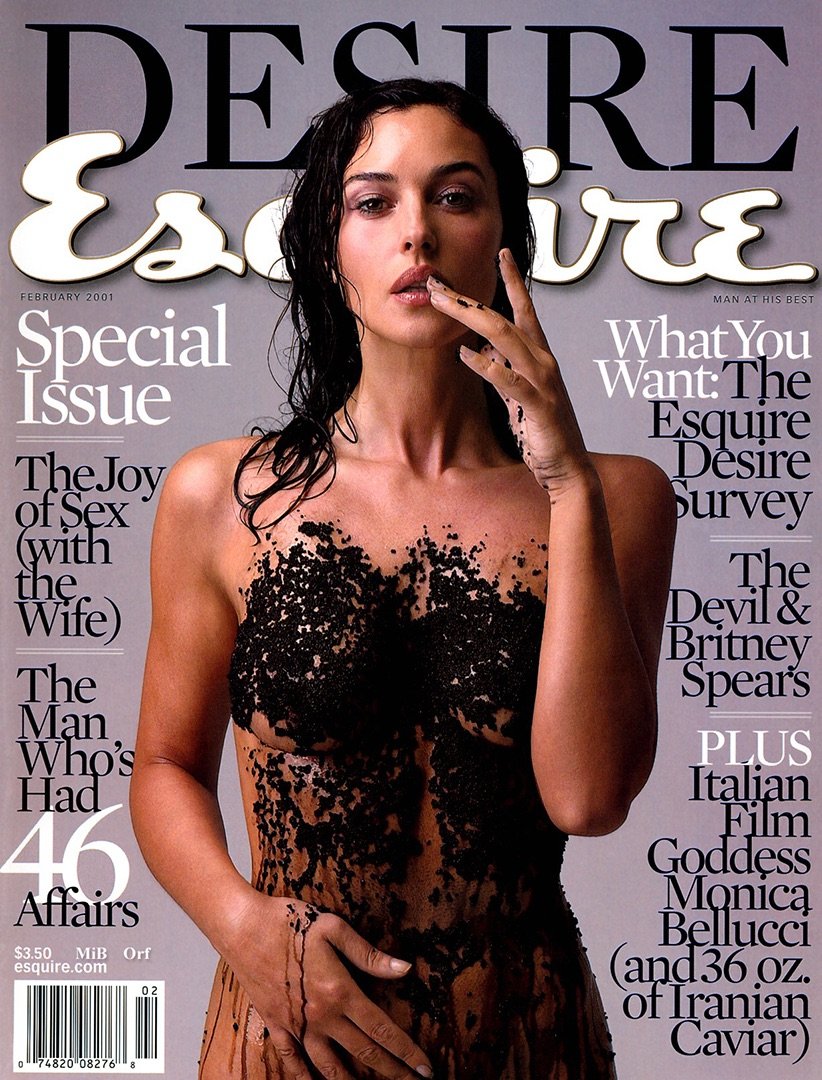

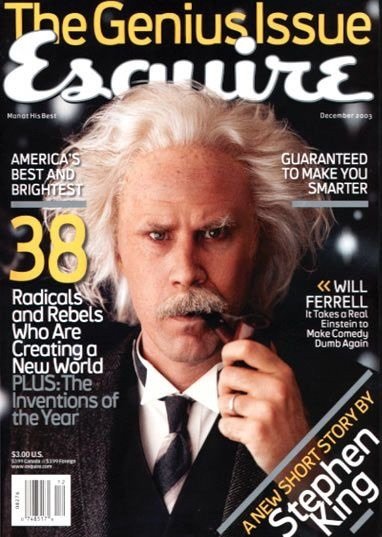

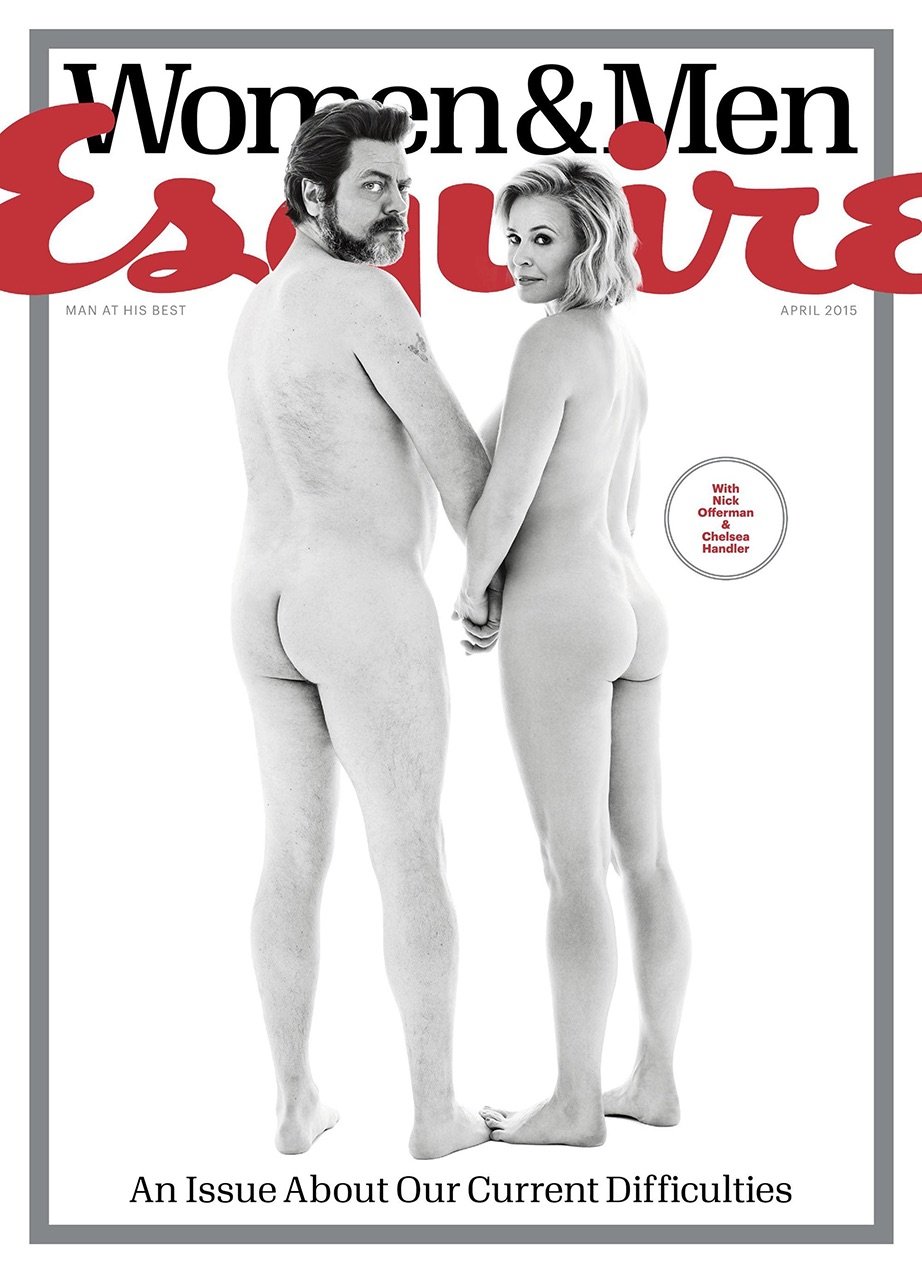

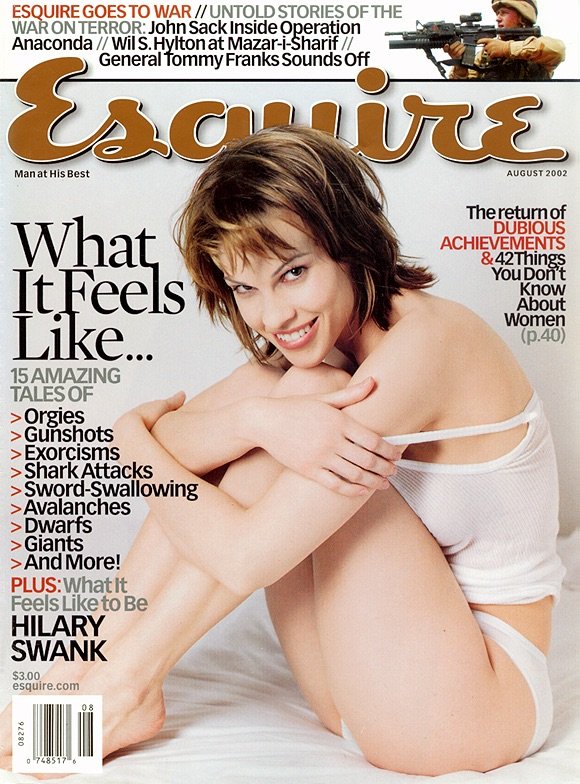

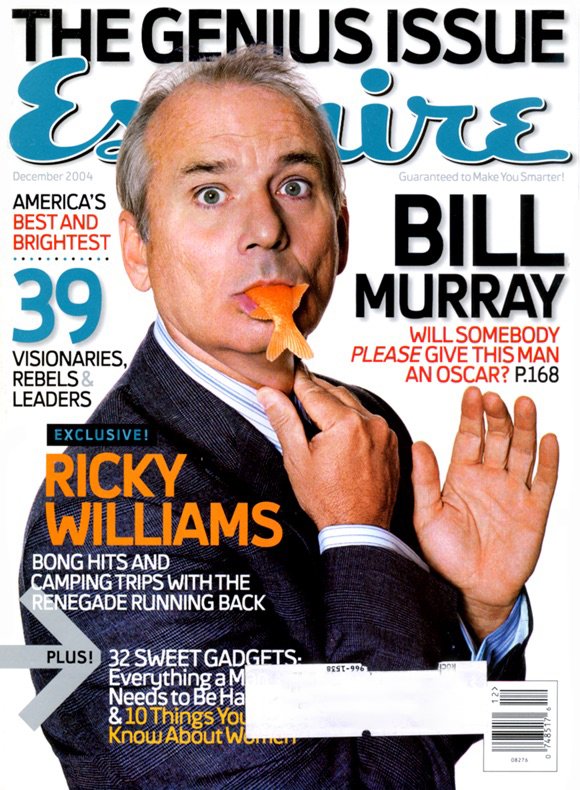

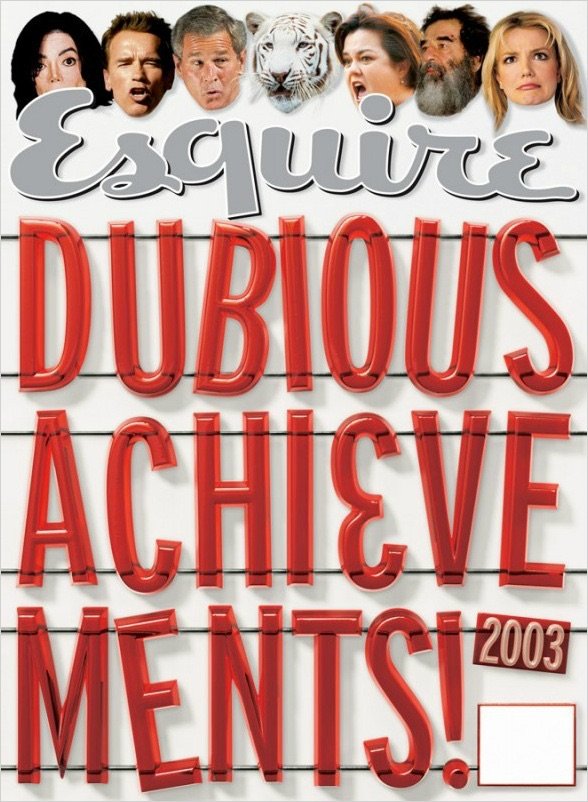

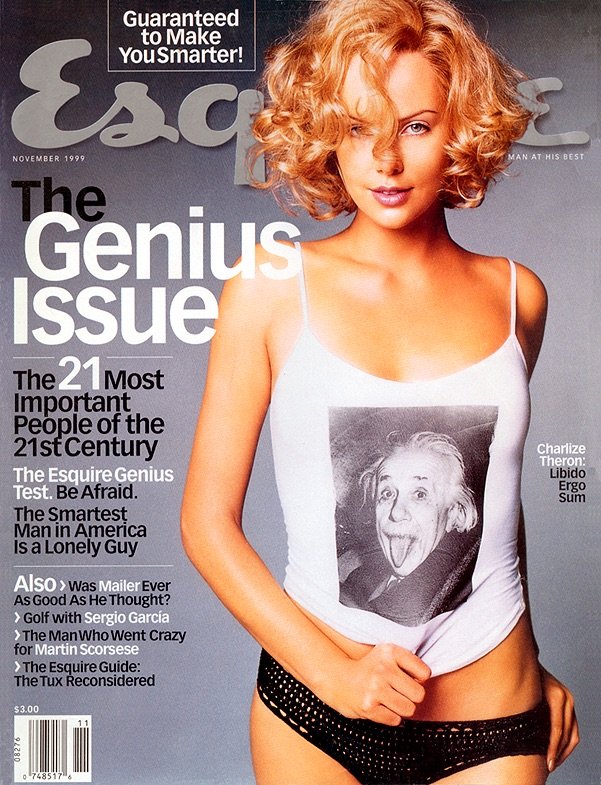

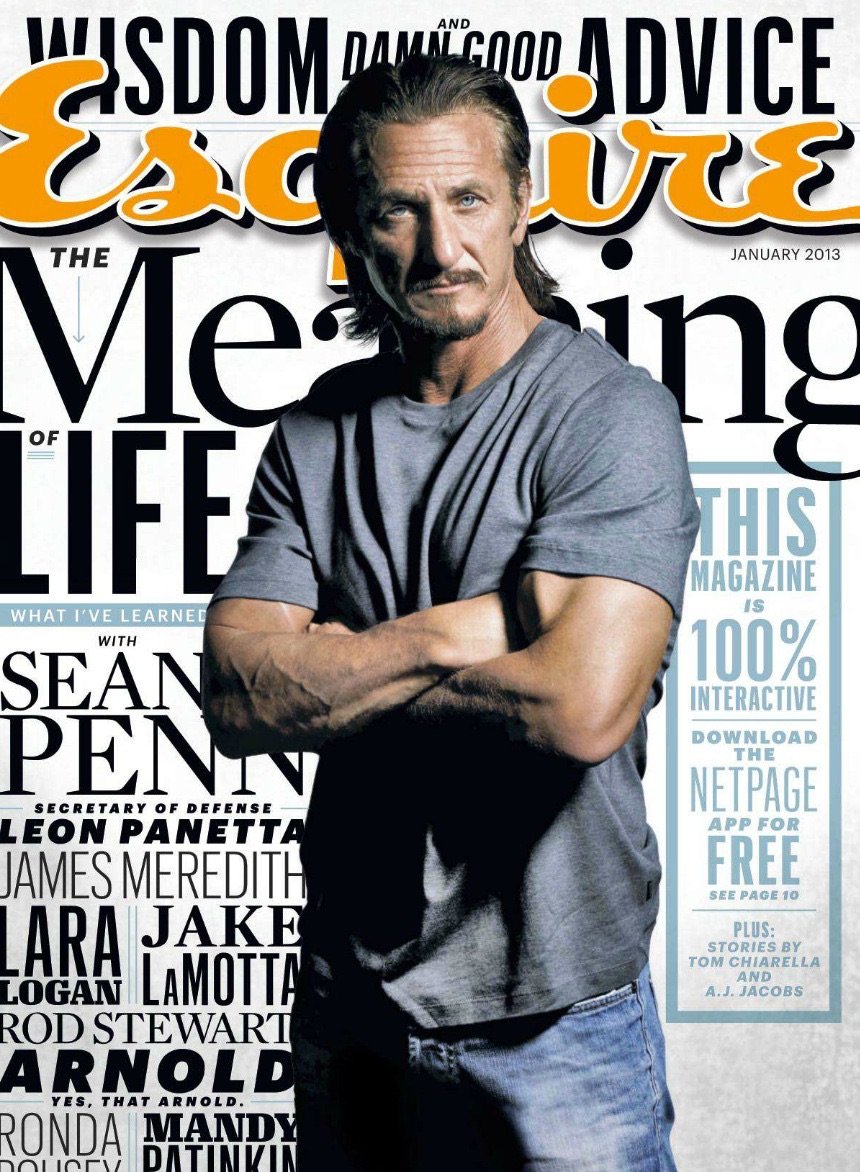

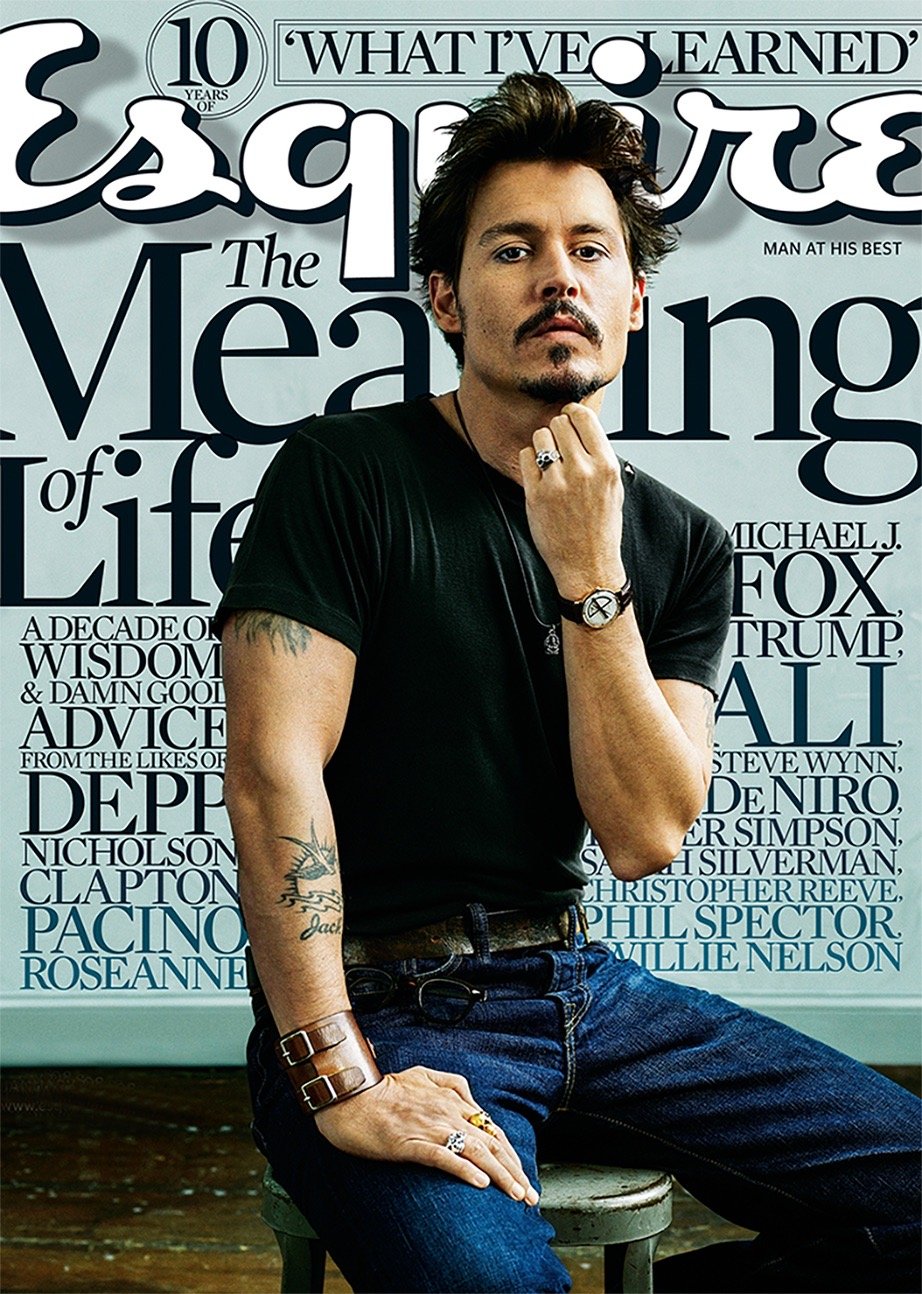

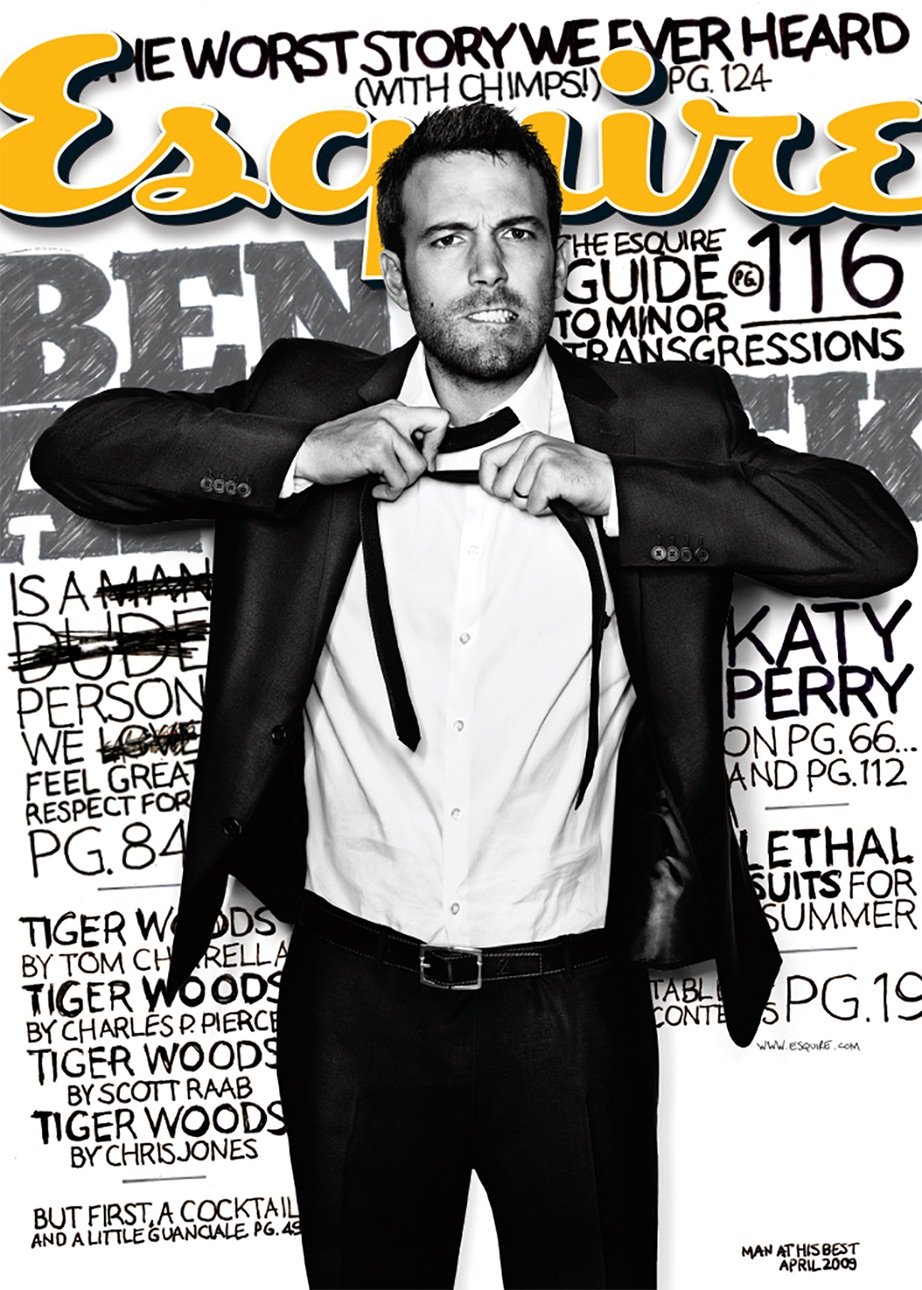

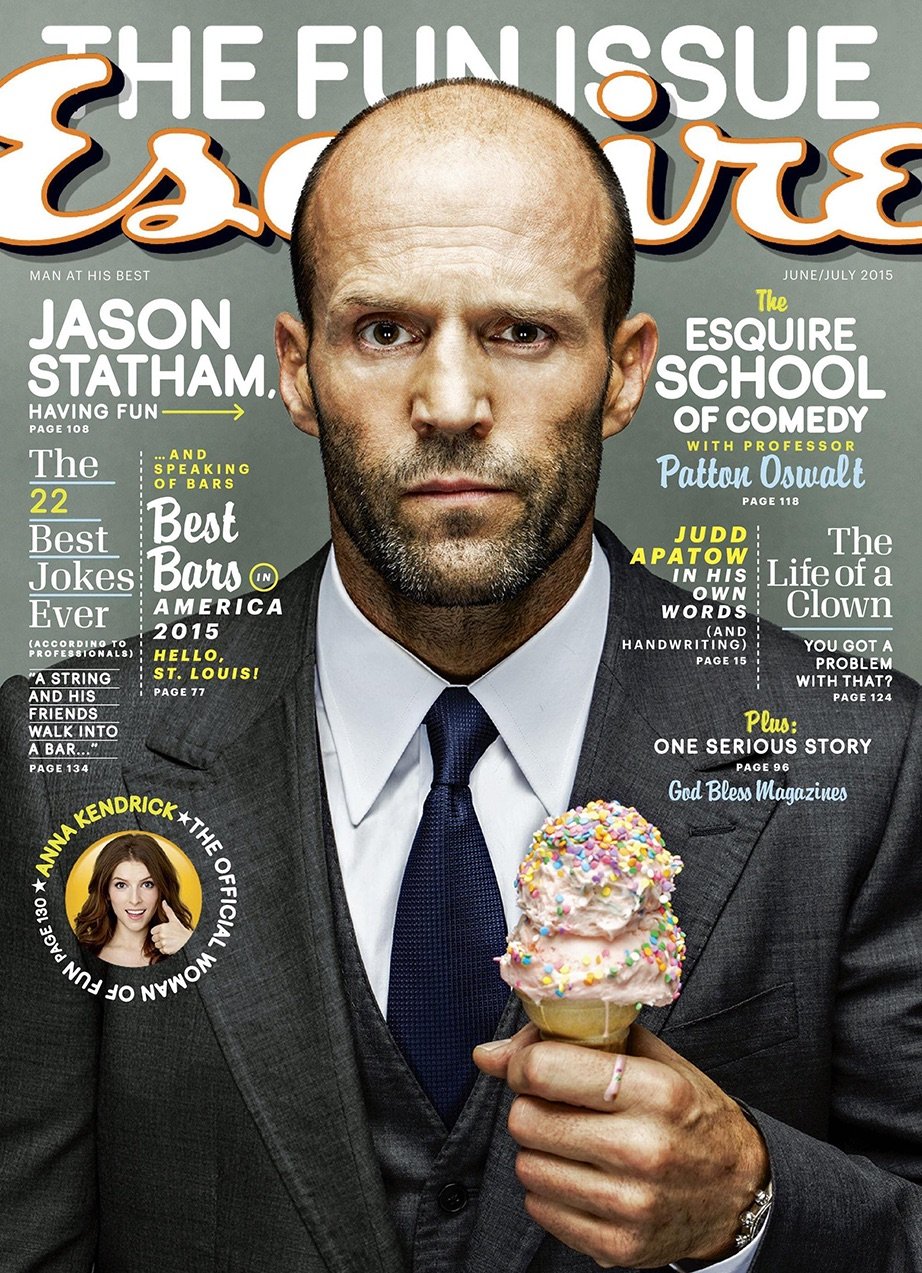

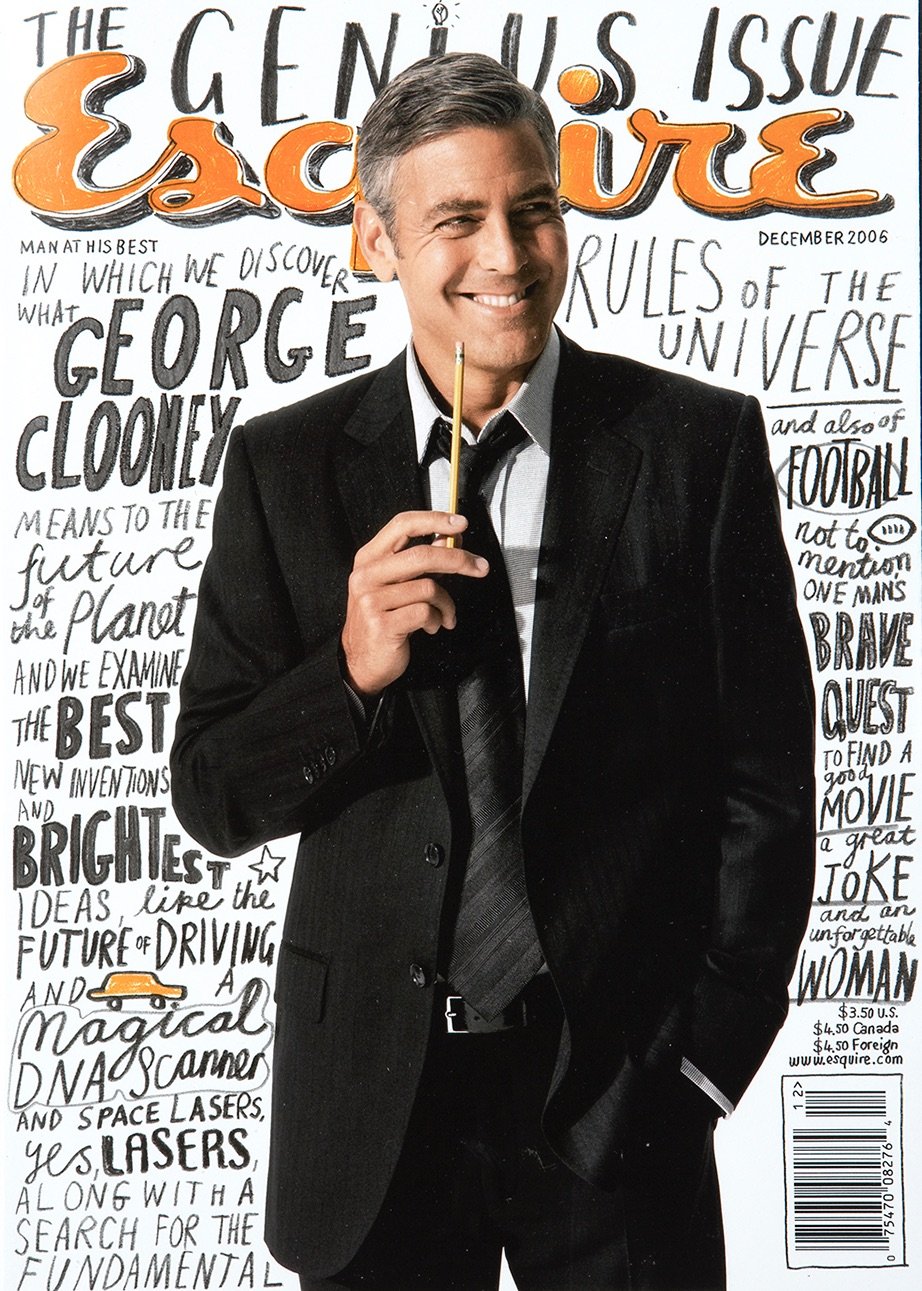

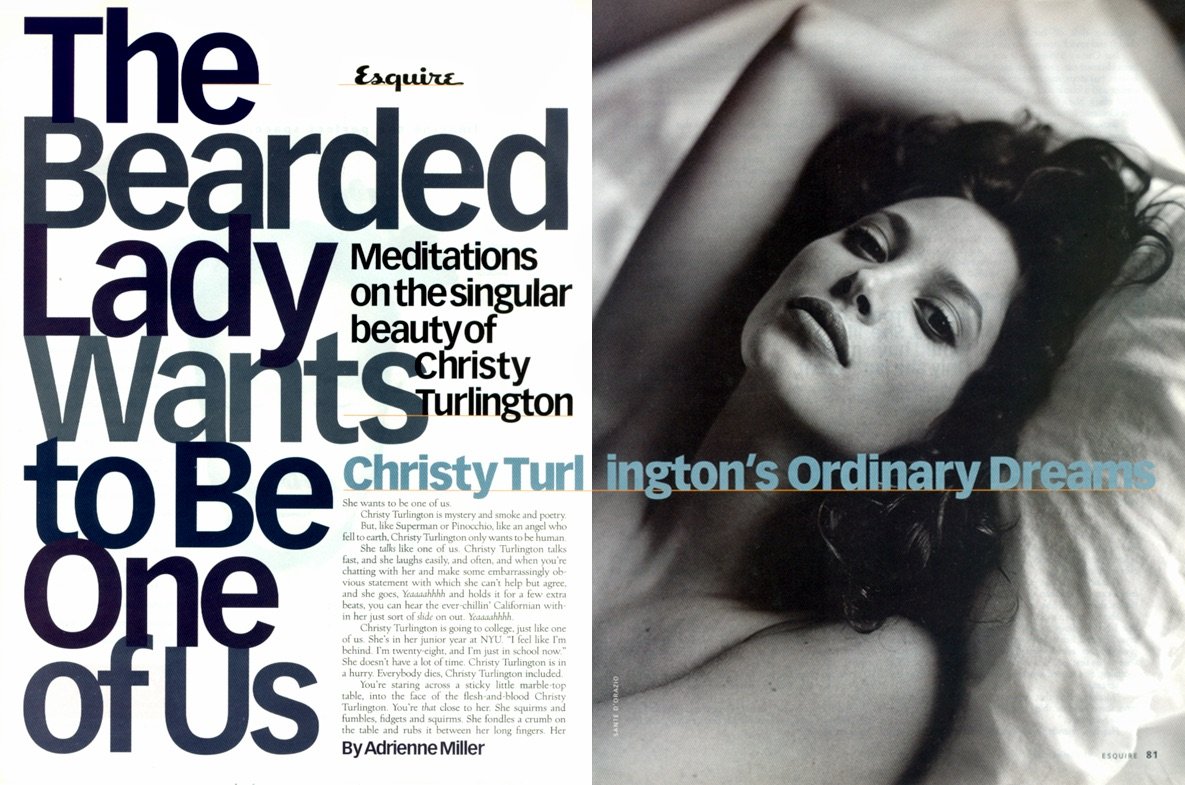

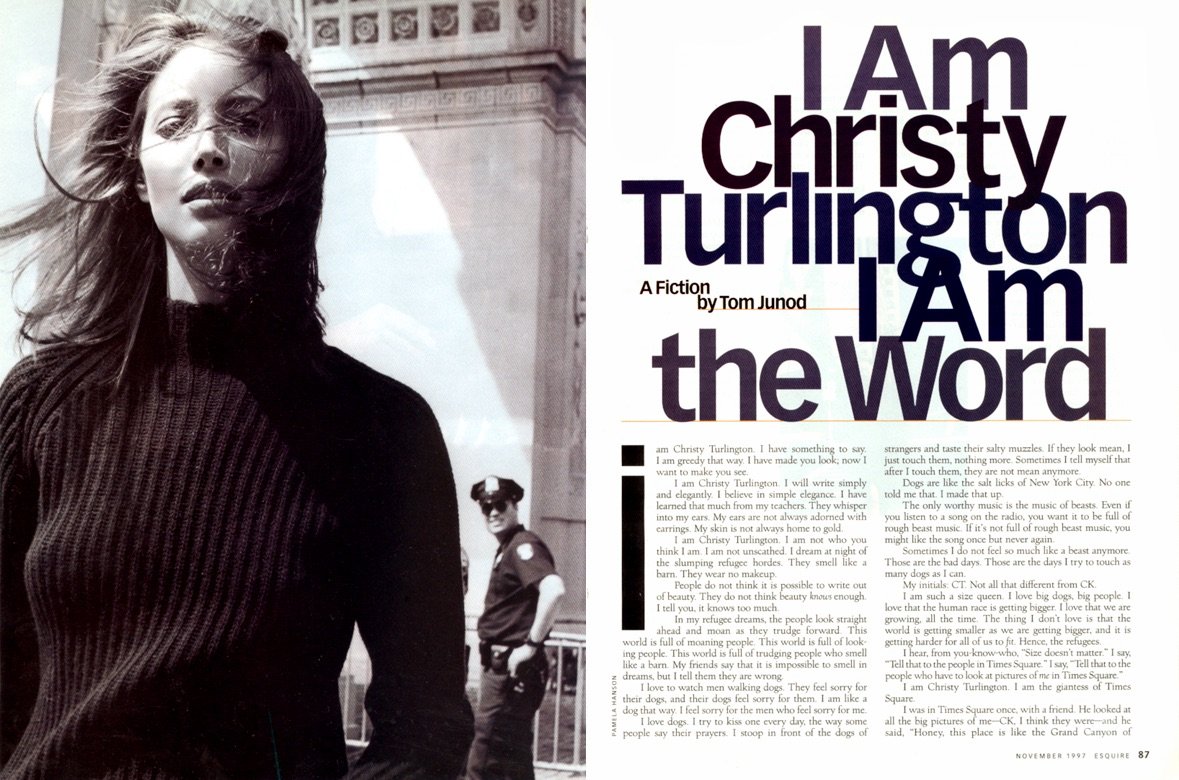

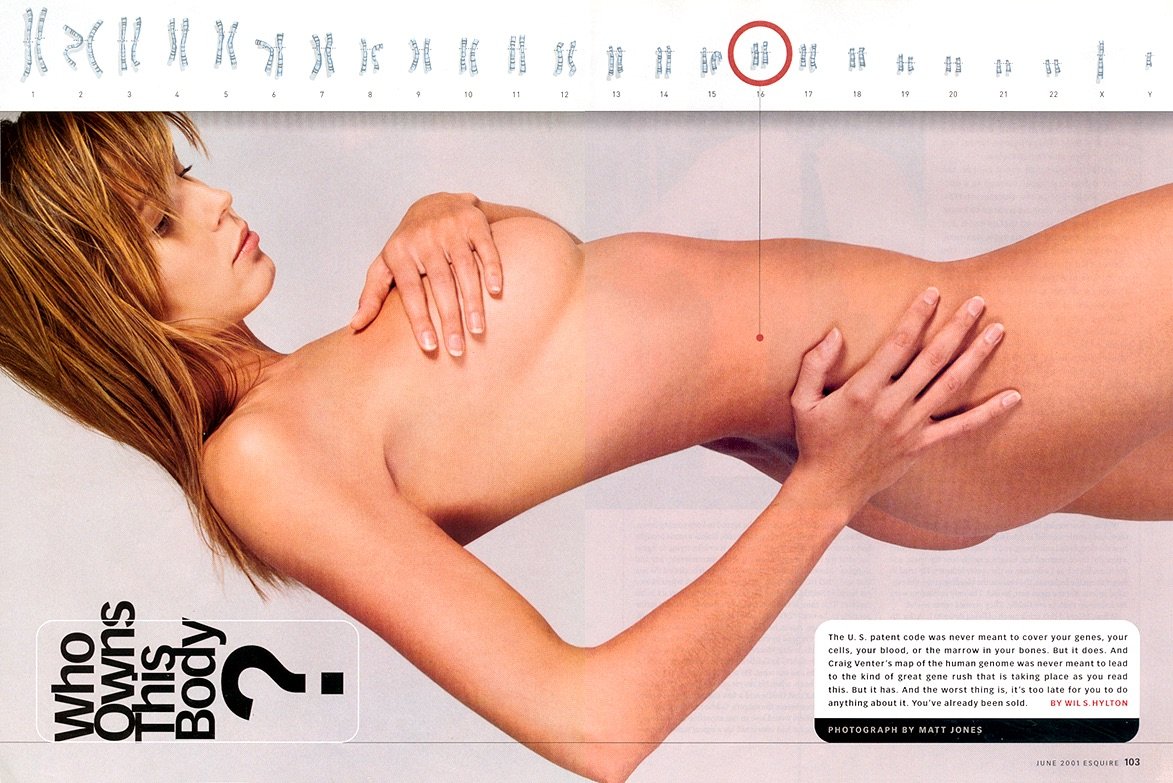

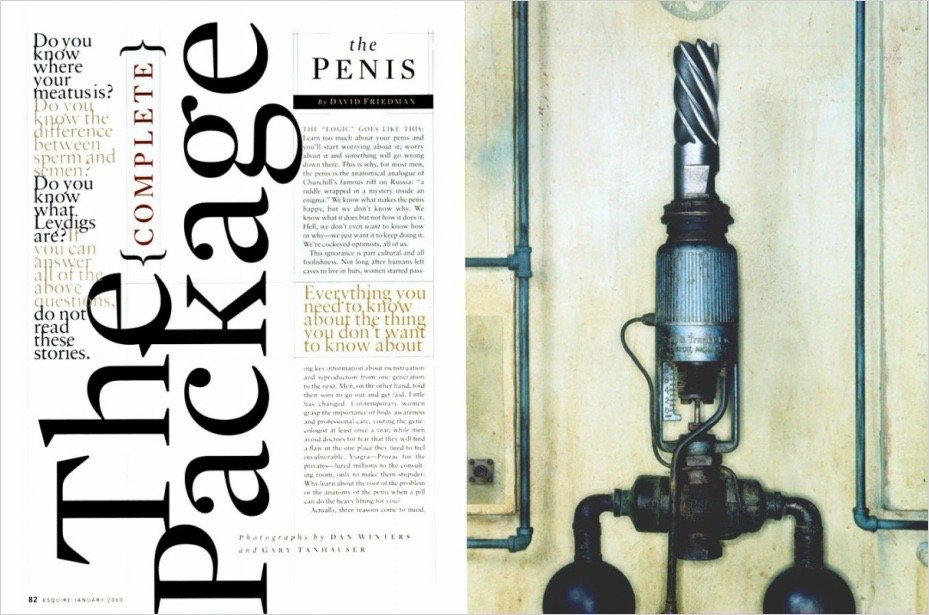

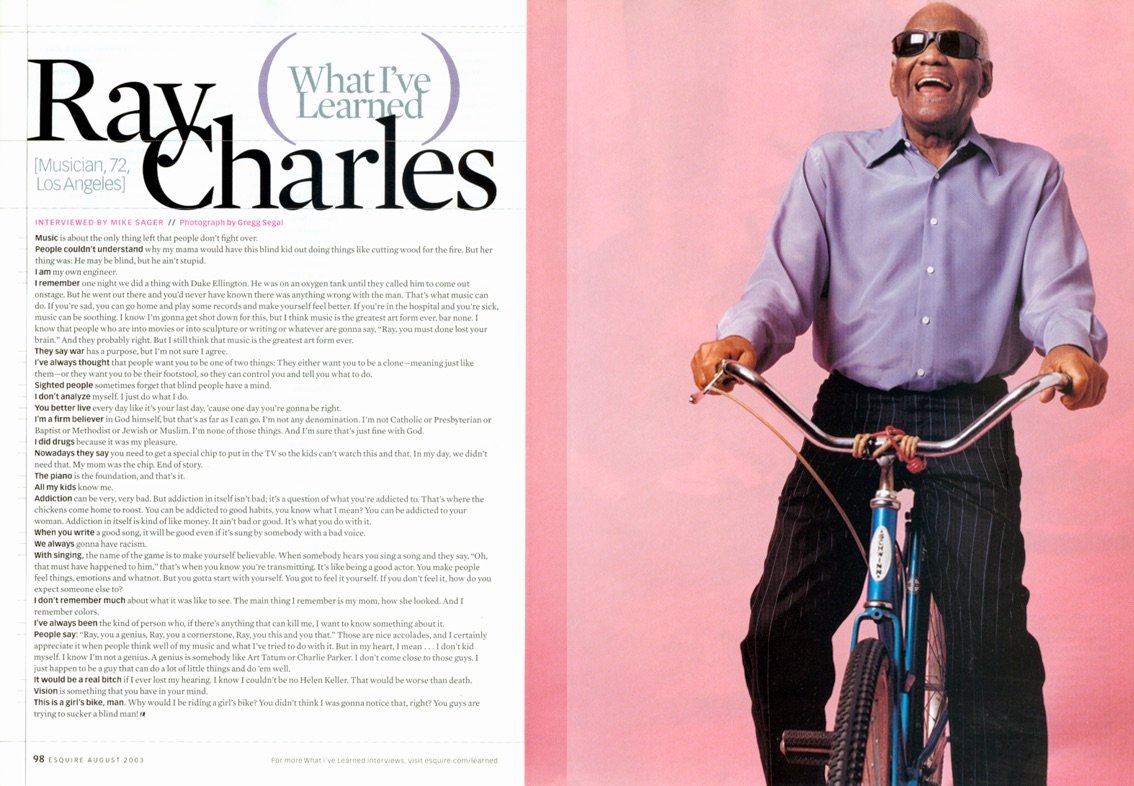

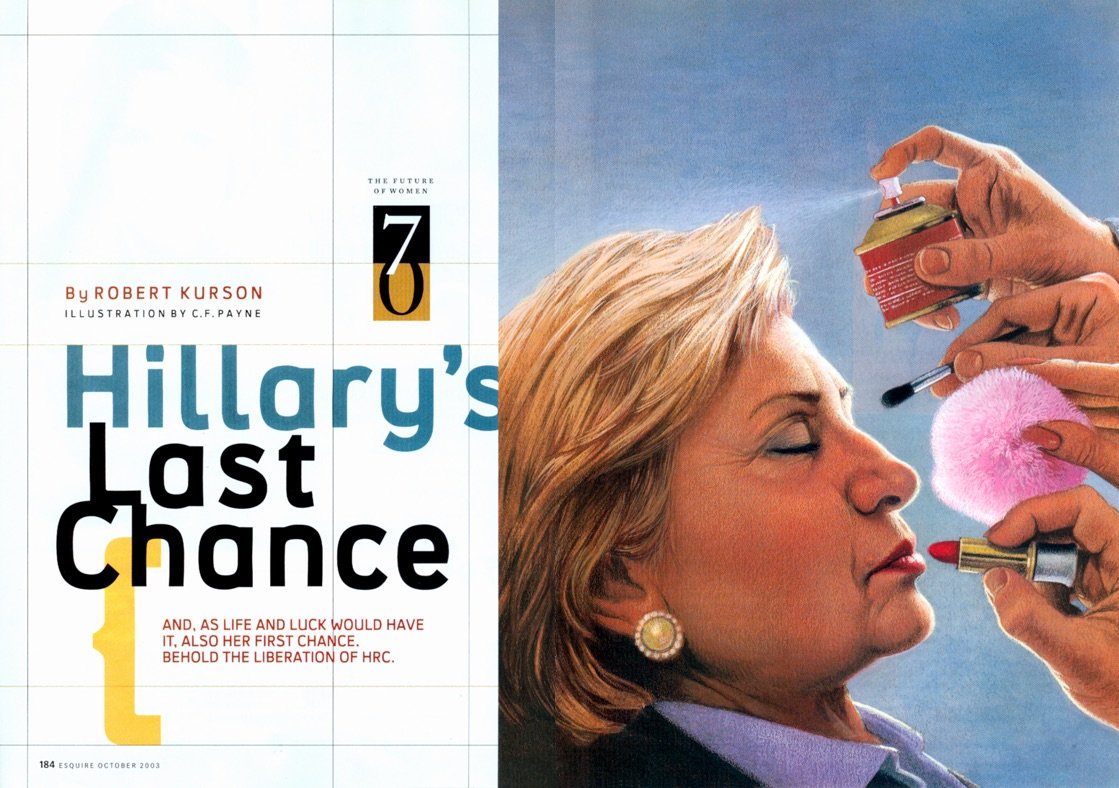

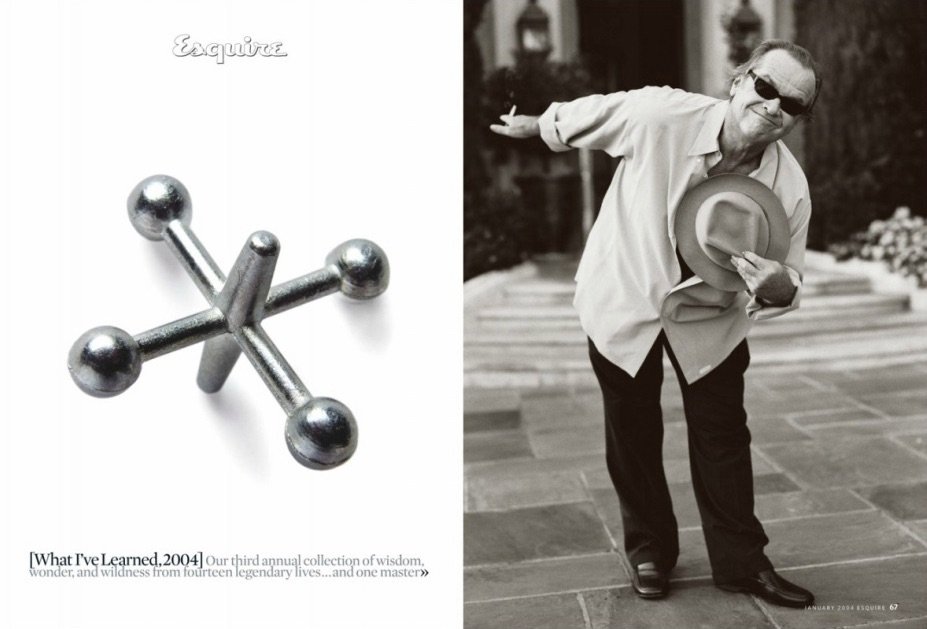

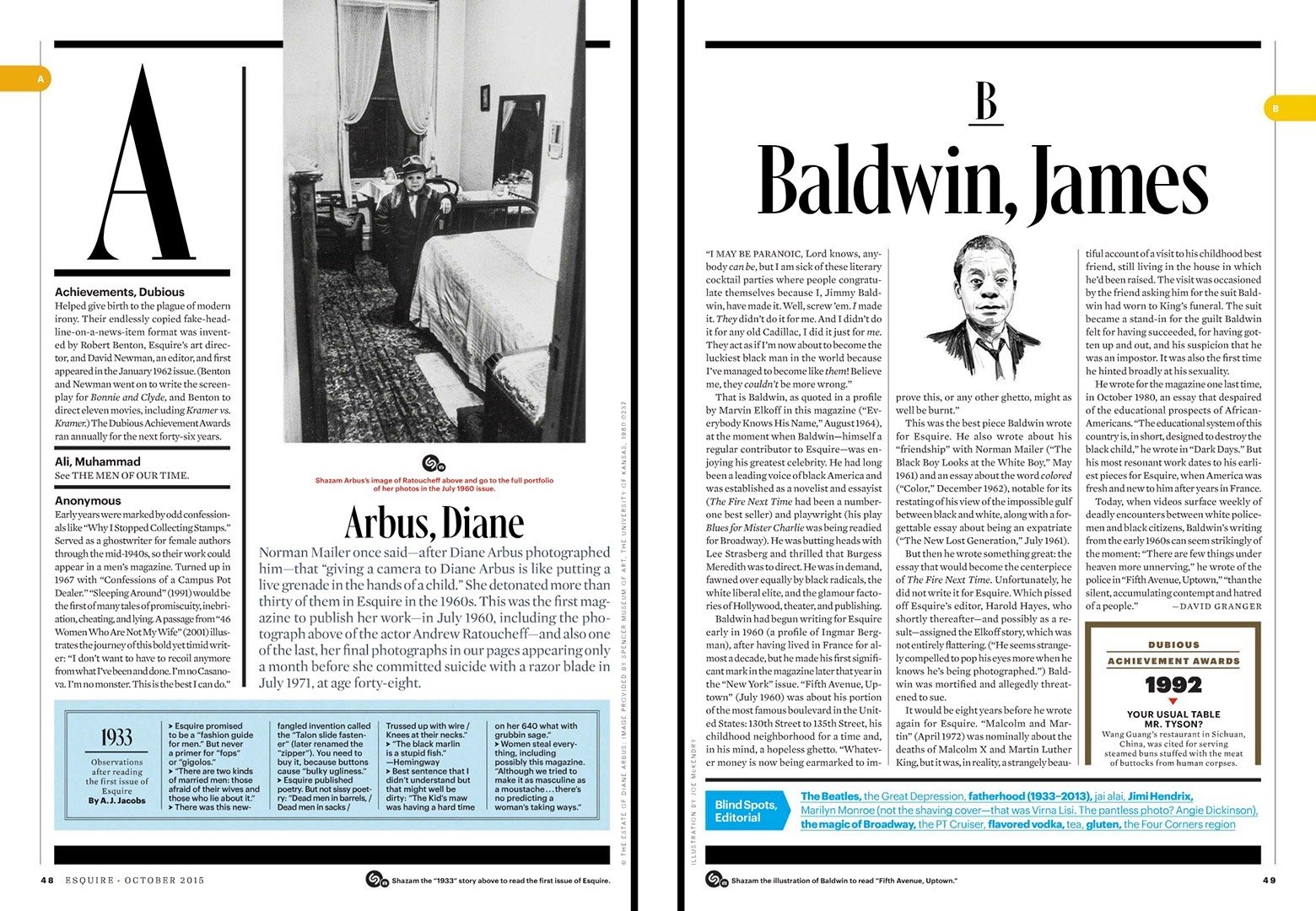

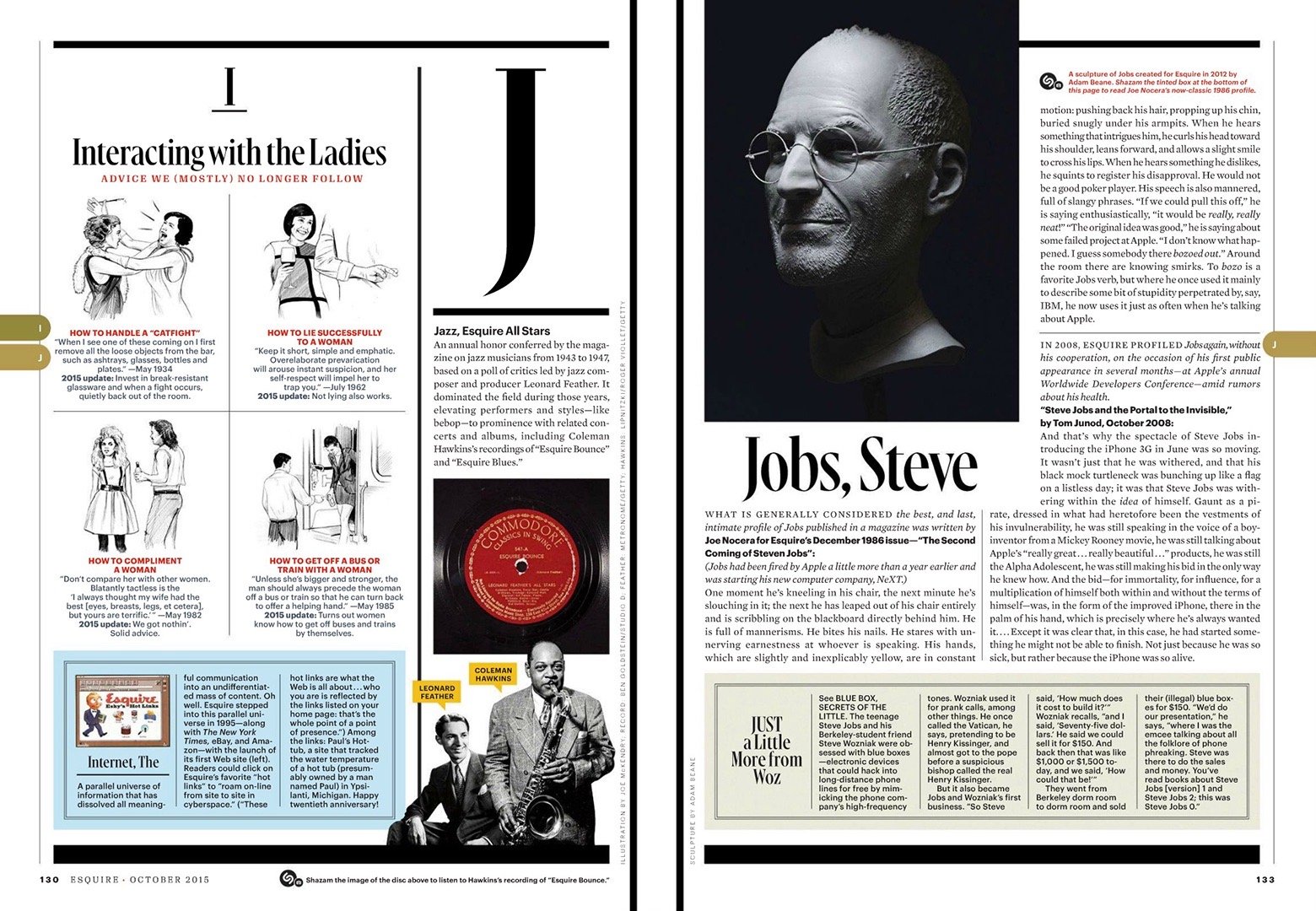

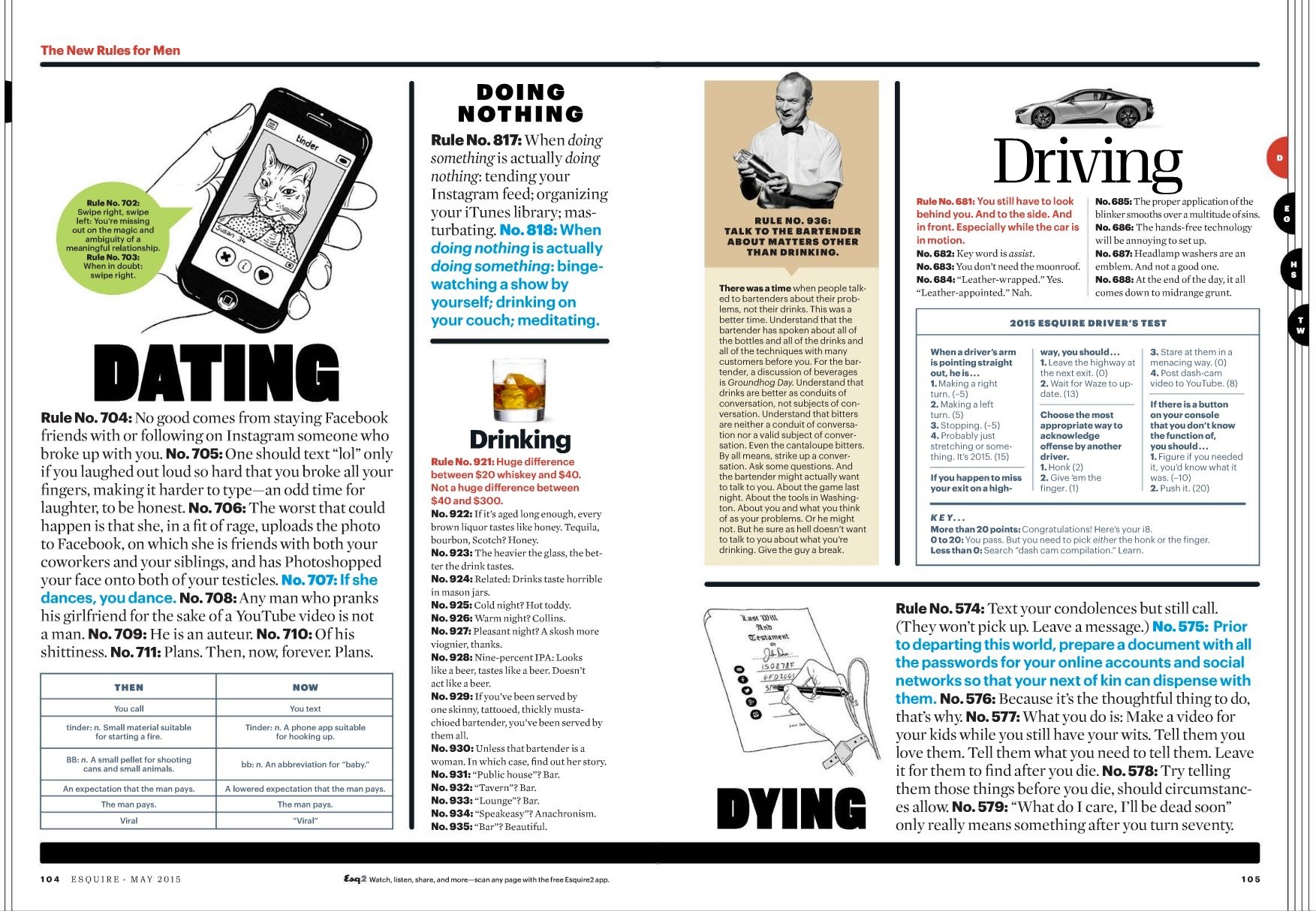

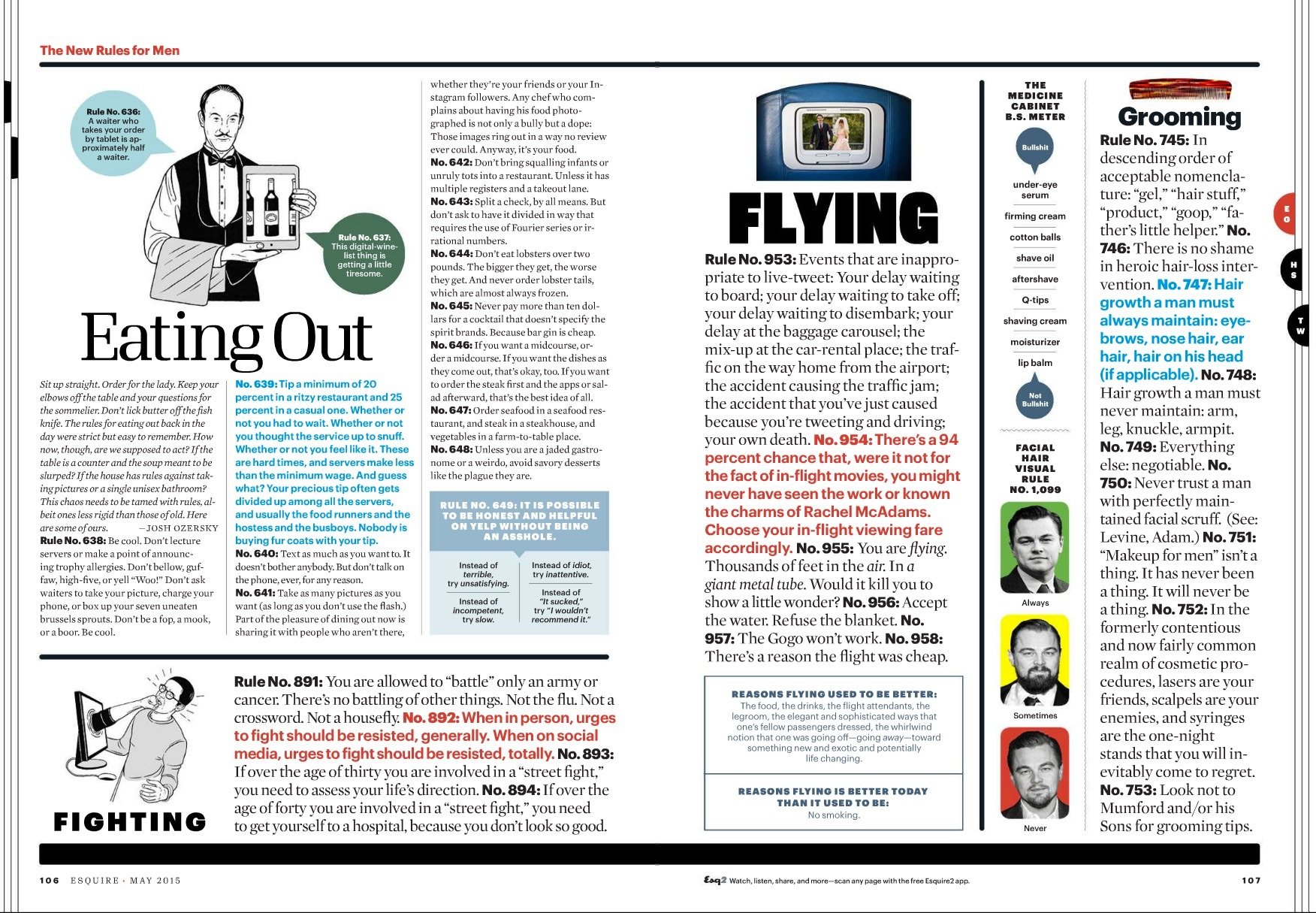

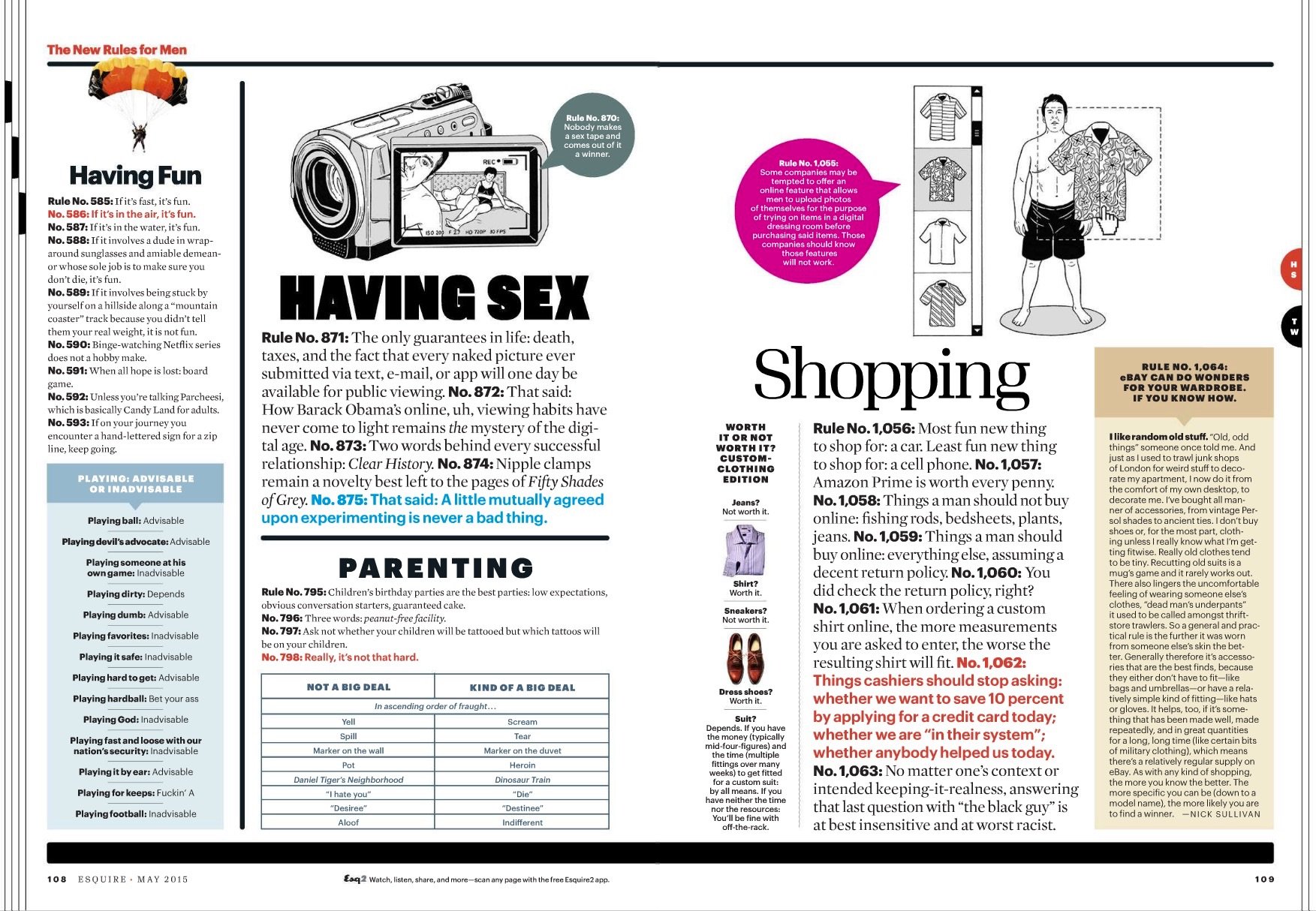

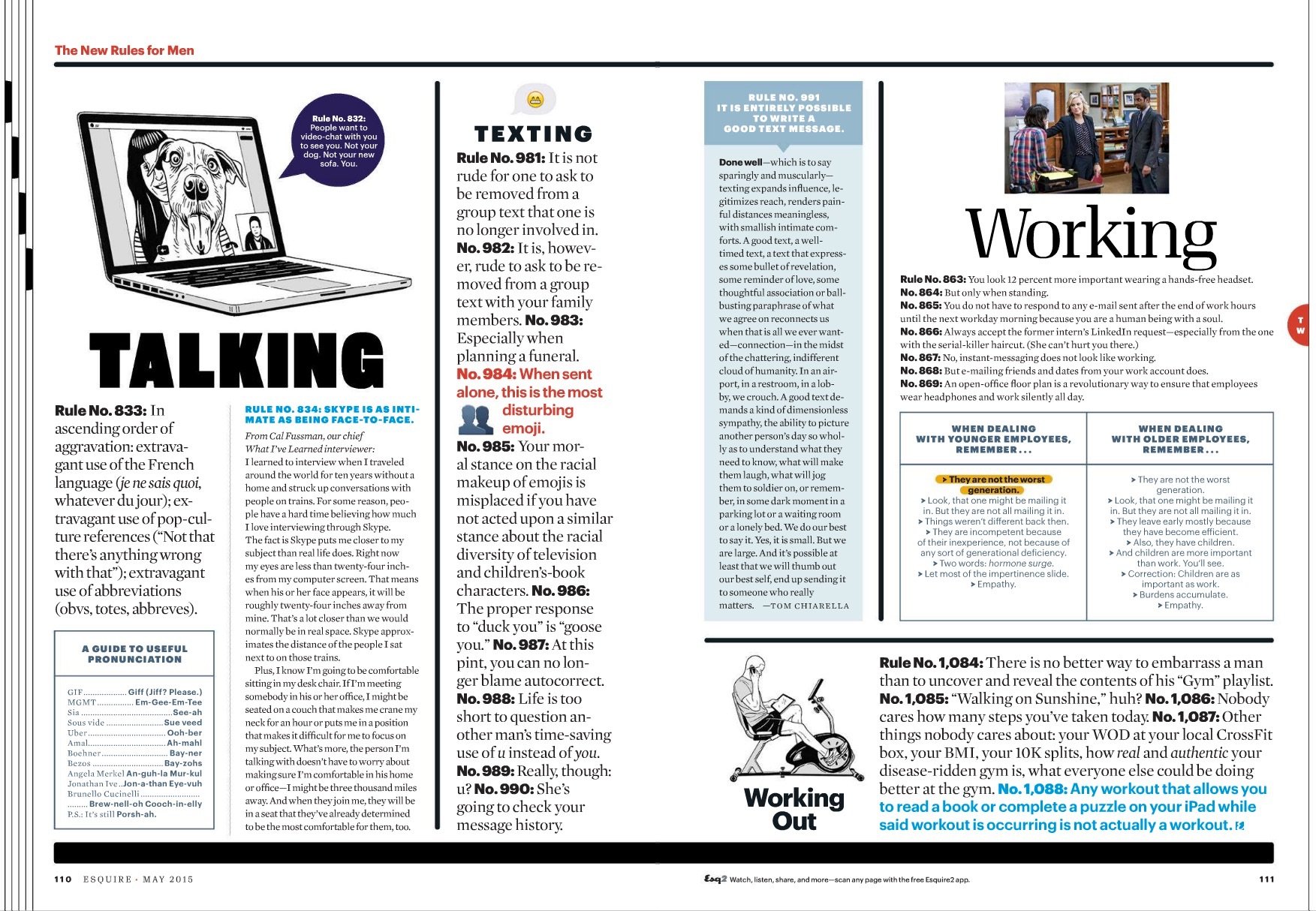

Upon taking over at Esquire, Granger’s instinct was to innovate—almost compulsively. Over the years, he’s introduced some of print’s most ambitious (and imitated) packaging conceits: What I’ve Learned, Funny Joke from a Beautiful Woman, The Genius Issue, What It Feels Like, and Drug of the Month, as well as radical innovations like an augmented reality issue, and the first print magazine with a digital cover.

Over and over, those who’ve worked with Granger stress his sense of loyalty. Ask any of his colleagues and you’ll hear a similar response: “David Granger is one of the finest editors America has ever produced. He also happens to be an exceptionally decent human being.”

At his star-studded going-away party after being let go by Hearst in 2016, Granger closed the evening with a toast that said it all: “This job made my life, as much as any job can make anybody’s life. It had almost nothing to do with me. It had everything to do with what you guys did under my watch. I’ve done exactly what I wanted to do—the only thing I’ve ever wanted to do—for the last 19 years. I’m the luckiest man in the world.”

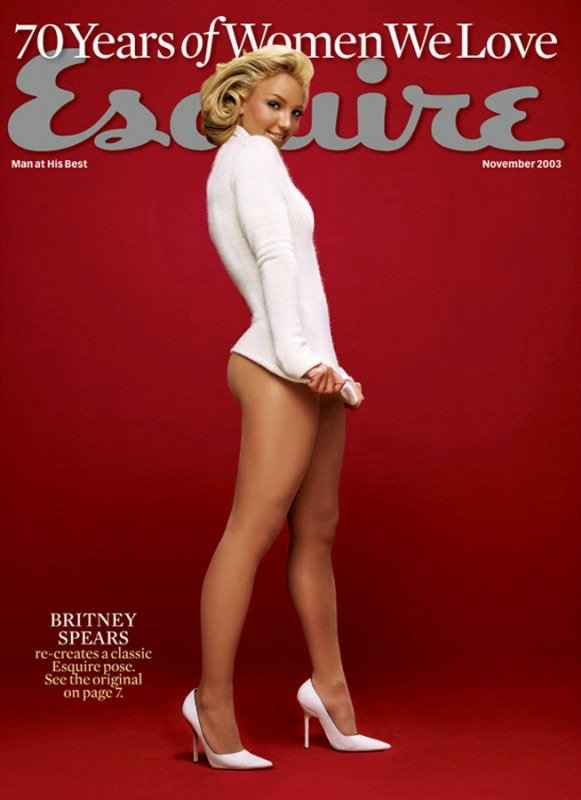

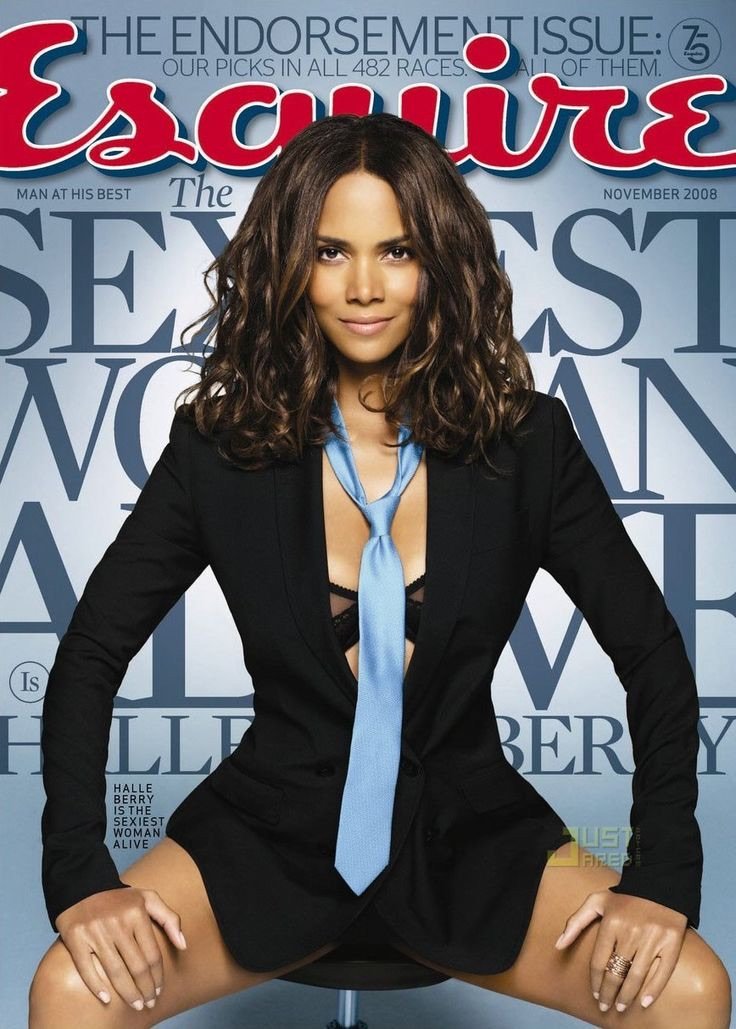

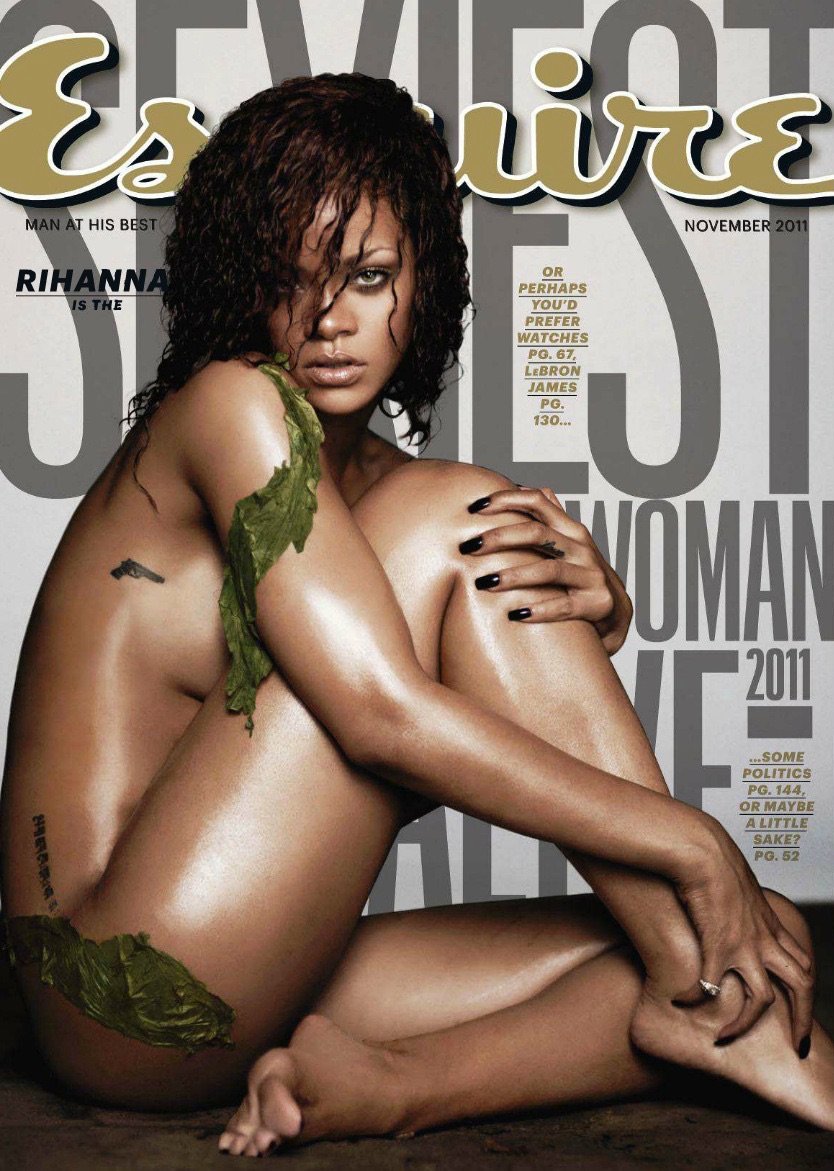

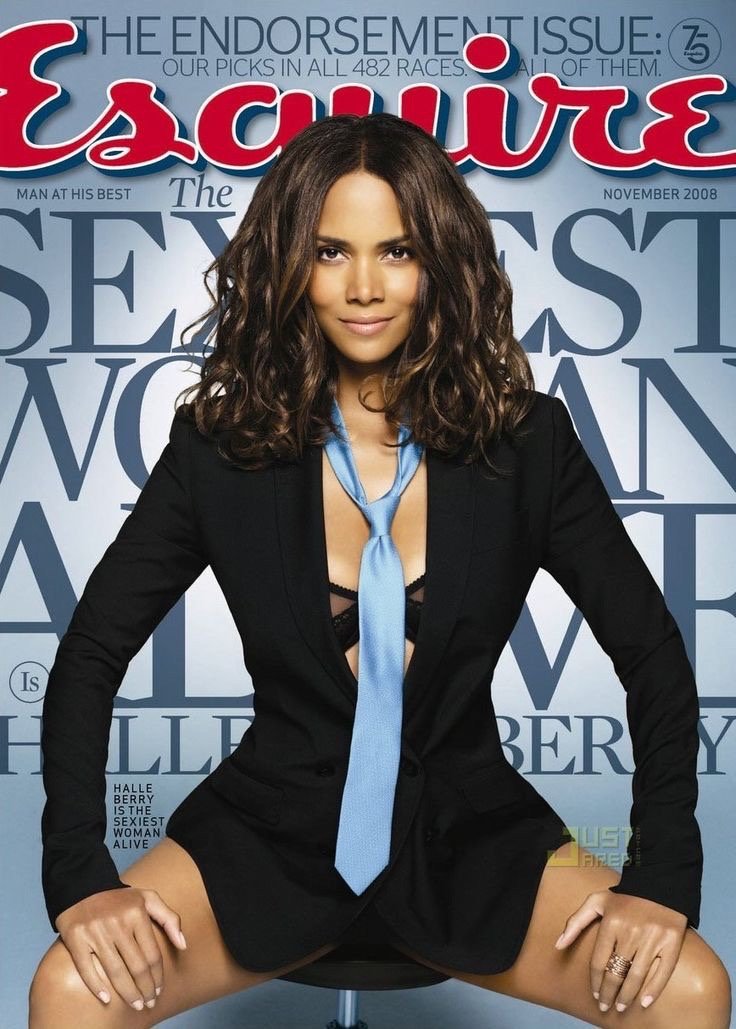

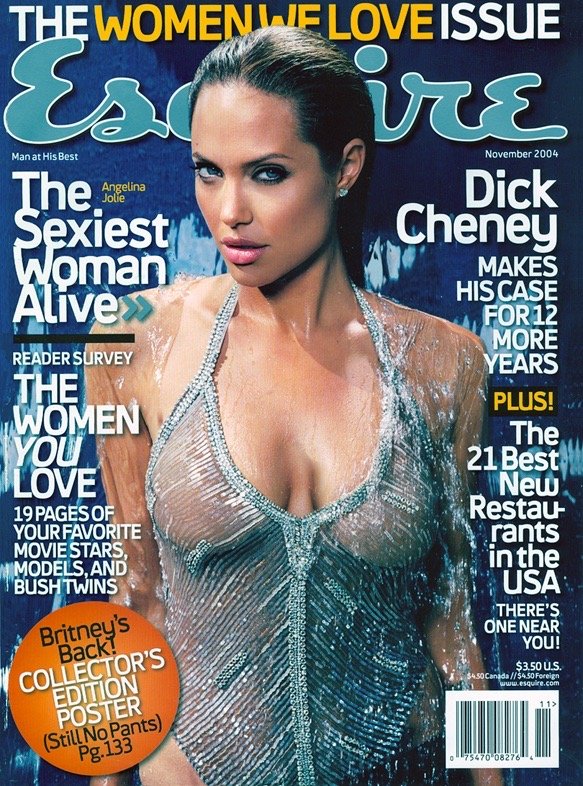

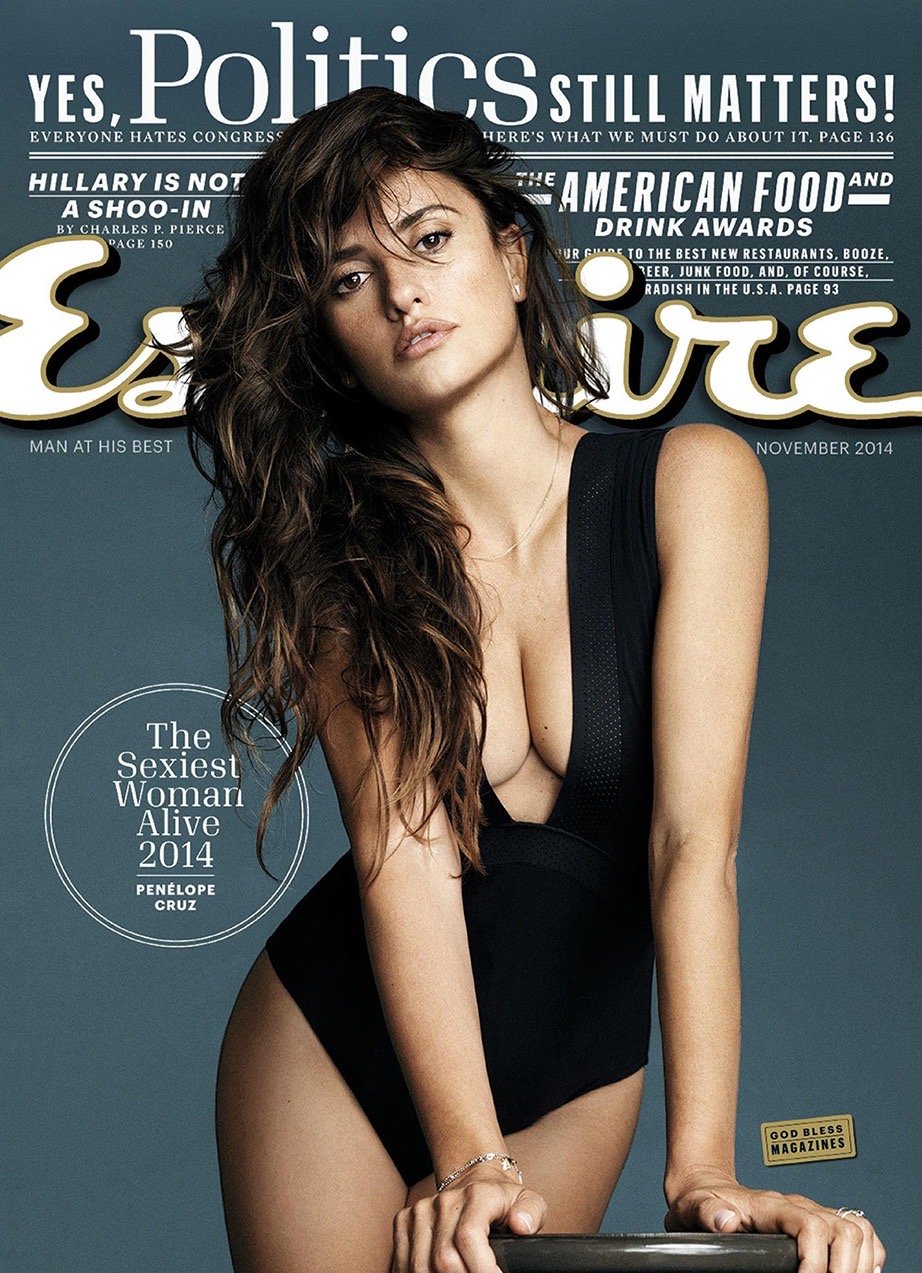

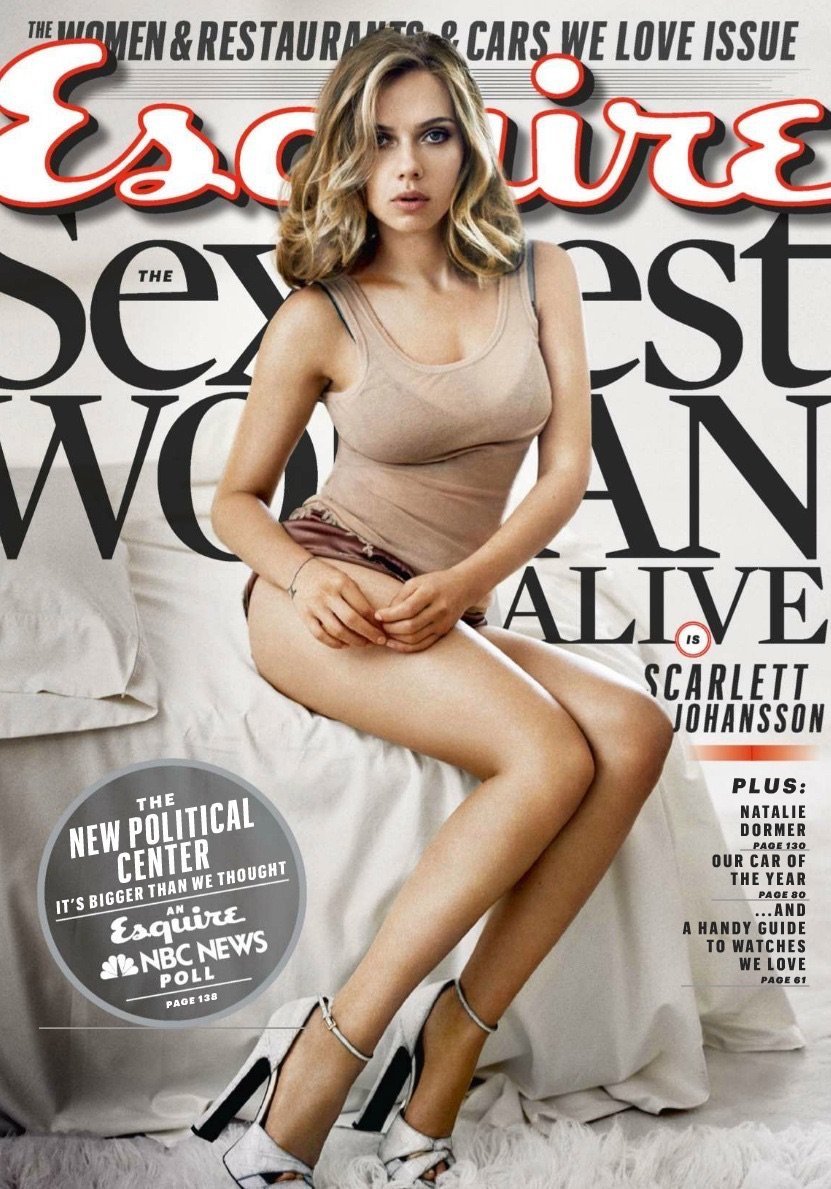

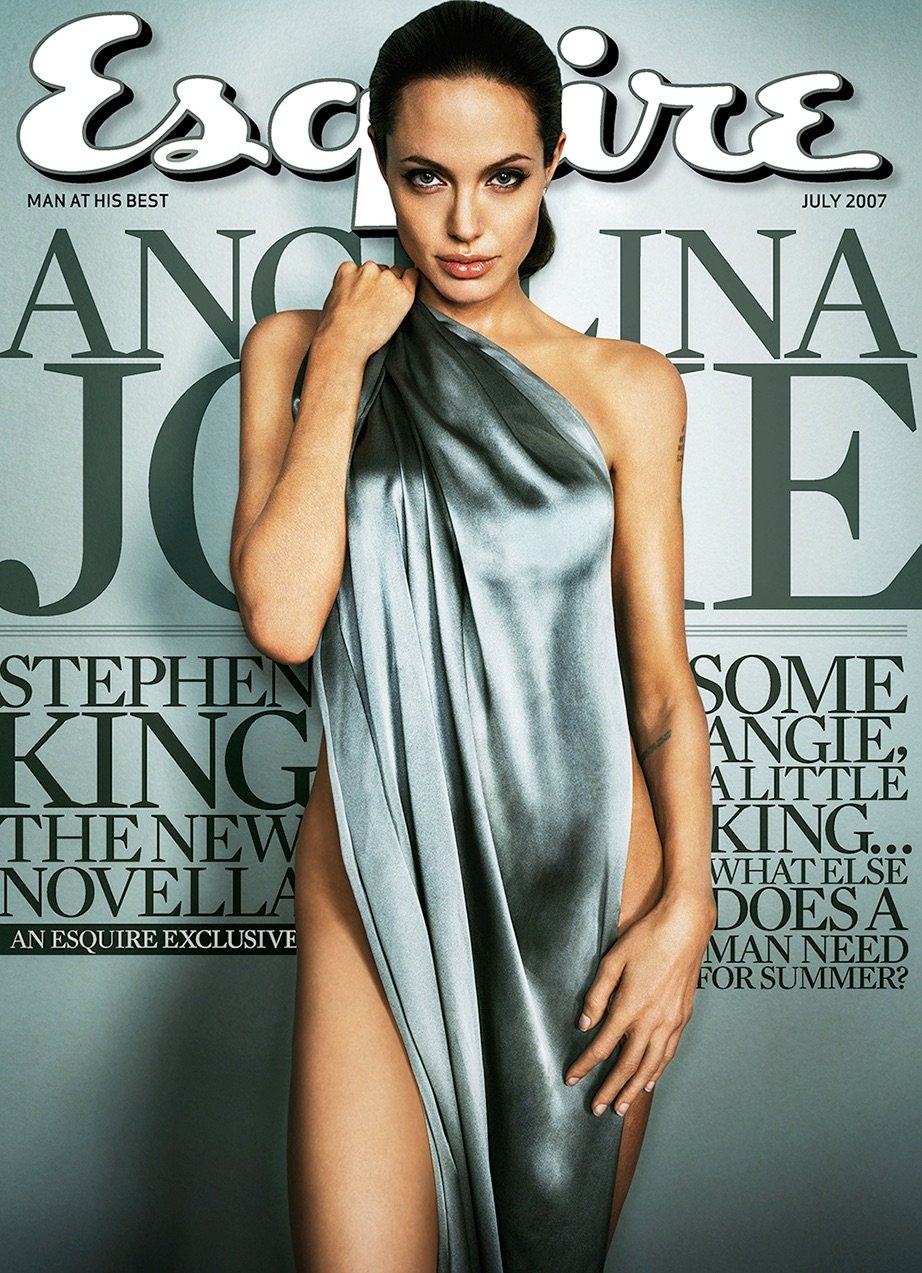

We talked to Granger about retiring some of Esquire‘s aging classics (Dubious Achievements, Sexiest Woman Alive), his surprising and life-changing Martha Stewart Moment, and what really went wrong with the magazine business.

Sean Plottner: So, David, let’s start with how you got your big break early in your career.

David Granger: Which big break are you speaking of?

Sean Plottner: Well, that would be the legendary magazine, the title that helped launch the careers of numerous publishing grades. From David Granger to Roger Black to Kermit the Frog.

David Granger: Uh … you’re speaking of Muppet Magazine?

Sean Plottner: Muppet Magazine. Tell us your Muppet story.

David Granger: Well, I went to the Radcliffe Publishing Course in the summer of 1982. Got out of that, moved to New York. Was homeless for six or seven weeks. Eventually I managed to hit the big time when I got a job for, I believe, $10 an hour writing chapters in a gardening book.

So I wrote chapters. They provided me with all the research. I wrote chapters on bonsai and pruning and perennials and annuals and stuff like that. And that was my big break in publishing. But shortly after that, I somehow managed to get an interview with Katie Dobbs, who was the editor-in-chief and the only editorial employee of the startup magazine, Muppet Magazine, the quarterly magazine, the quarterly humor magazine for children aged eight-to-12.

And I was Katie’s assistant and I was not a particularly good assistant because I wanted to do absolutely everything else. I sat in on writer’s meetings. I worked in the design department. I did absolutely everything but answer Katie’s phone. And after 18 months, she let me know one day that. She thought it would be better for me if in the next two weeks I found my next opportunity.

“I didn’t know exactly what Esquire was, but I knew it was important. And I started reading it.”

Sean Plottner: Oh my! She didn’t bring in the Cookie Monster to do that?

David Granger: No. No, though I did get to play Rowlf the Dog, though. Not in video or audio. I just wrote in his voice as our book reviewer.

Sean Plottner: Ah. Book reviews. I did see that Kermit was on the masthead and I believe he had a column in most ...

David Granger: Kermit, I think, was the boss, and I think he wrote the editor’s letter most months. That was quite a while ago and it was, as you say, quite the launching pad.

Sean Plottner: Yes, indeed. Well, let’s back up even more now and see if you can tell us a little bit about growing up. Where’d you grow up and what’d your parents do?

David Granger: I grew up around the United States. My dad was a social worker. He and my mom were both native Californians. And my mom’s still alive, my dad’s not. And we lived in various places in California when I was little, but I mostly remember San Diego, where we lived until I was 11 years old. My dad had successfully gotten a couple of master’s degrees, one in social work, one in public administration, and then decided he needed a PhD.

So we moved to Wellesley, Massachusetts, where he got a PhD at Brandeis. We lived there for three years and moved to Lexington, Kentucky, where he had his first big academic job as associate dean of the graduate school of social work. And then after two years there, we moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, where I finished my high school career, went to my senior year in high school there, and then went to the University of Tennessee, basically because it was the only place that had to take me.

So my mom was a very effective housewife, but once her kids were all gone, she started. The first of what became three different organizations, and this started in the, I guess the early eighties, the first one at the University of Tennessee called Human Animal Bond in Tennessee (HABIT), where she trained humans and their pets to work with professional therapists in nursing homes and stuff. But then at the Patricia Neal Trauma Center at University Tennessee in the early days of trying to understand what autism was. All sorts of mental health issues.

And she had a volunteer network of like 275 people in Tennessee then recreated that when they moved to Colorado. So she didn’t work when I was growing up, but worked for 45 years in animal-assisted therapy after that.

Granger got his first big break at Muppet Magazine.

Sean Plottner: What kind of early awareness did you have of magazines or media in general?

David Granger: I think I had the average awareness growing up in the sixties and seventies of things like, Reader’s Digest. “Humor in Uniform” was one of my favorite pages in any magazine.

And then probably starting with Highlights and all that kind of stuff. The first magazine I remember subscribing to was Sports Illustrated. But I didn’t really think much about magazines until I was in college when these two boys [Chris Whittle and Phillip Moffitt] from the University of Tennessee, who were about 10 years ahead of me, they graduated and they started this publishing company in Knoxville called 13-30, I believe it was at the time. Whittle Communications? What was it?

Sean Plottner: It was 13-30. Patrick and I are very familiar with it.

David Granger: But then didn’t it become Whittle Communications after that or something? Anyway, they bought this thing called Esquire. And I was a junior in college. I didn’t know exactly what Esquire was, but I knew it was important. And I started reading it.

And as a young man who had never been to New York, but knew that one day he was going to go to New York and live in New York, it became sort of my guidebook to how to become the kind of person who would leave Tennessee or somewhere else, move to New York and be a successful something, preferably employee of Esquire.

What Phillip Moffitt did was—he did this magical thing that very few magazine editors actually succeed at, which is to show their readers how to make their lives better. And while he’s doing that, while he is providing tangible benefit, he also coaxes his readers to stay around for just amazing pieces of storytelling or amazing photo displays or whatever it is. All the stuff that you do because it’s ambitious and because it’s art.

But if that’s all you do, then you’re Harper’s and your circulation is a hundred thousand. So I mean, Phil had a magic—I think his era was my first era of Esquire and, looking back on it, having worked at Esquire for a while, I think it was one of the better eras of Esquire.

Sean Plottner: As a matter of fact, Patrick and I were both working for 13-30 at that time.

David Granger: In the eighties?

“What Phillip Moffitt did was—he did this magical thing that very few magazine editors actually succeed at, which is to show their readers how to make their lives better.”

Sean Plottner: Yeah. I was an intern in ’83 and went to work there after I graduated. And, you know, Patrick and I started … we were talking about this a couple weeks ago. We started our own little—it was mostly Patrick’s idea—we had a monthly paper, The Knoxville Paper. This was ’85. And, we put out a few issues, had a little bit of success, certainly got our hands dirty and Whittle and Moffitt one day called us up to their executive suite, as it were, in Knoxville, and claimed they wanted to meet us. And we thought, “Hey, someday we’re going to be the publishers of Esquire.” So who knows? If things had turned out differently, you could have ended up working for us.

David Granger: I’m sure that would’ve been better than working for Hearst.

Sean Plottner: So at the University of Tennessee, what did you major in?

David Granger: I majored in two things: English and History.

Sean Plottner: And did you practice or get involved in journalism in any way at that time?

David Granger: I never did. I didn’t take a single journalism course. I left the University of Tennessee and went to graduate school at the University of Virginia. Eventually I got a master’s in English. But I never studied journalism. Why do you ask?

Sean Plottner: And what was your thinking in terms of any kind of so-called career path at that time? Did you have ambitions to do something specific?

David Granger: I went to University of Virginia, sort of thinking that maybe I’d teach. And yeah, my father had been an academic, it seemed kind of natural. And I was quickly disabused of that notion. When I got to UVA, I was deeply intimidated by my professors and stuff, and I was so intimidated that I went before classes started and I read as many of the papers that they’d written as I could, their academic papers and stuff.

And almost as soon as I started reading those things, it was like, “Wow, this is not something I want to do.” You know? I mean, they seemed small. And I think that’s when I first started thinking about what I could do that seemed significant. Or artistic. But that had a broader reach than what your typical professor could have.

And I had a roommate my second year—I think his name was Paul Birdsall—and he had a subscription to Esquire and I’d read it when I was in high school and your boys bought it, but then it was coming into our house every month and I got to see what it was. And it was at that point that I started seriously thinking that one day, you know, maybe magazines were something I could do.

It wasn’t sexy, but Granger credits his time at Adweek and Mediaweek with teaching how to edit a magazine.

Sean Plottner: And you had a hankering to get to New York City at some point?

David Granger: Yeah, I’d never been there. It seemed like the place I had to go. So the first time I came up was to visit a friend of mine I’d known from the University of Tennessee.

That was a short visit. He lived out on Long Island and we only got into the city one night and it was like really early eighties. And these guys out on Long Island were scared shitless of the city. It was a rough place. And I remember they took the wrong bridge and we ended up in Harlem and these guys were shaking in their boots and like, “Are we going to make it there?” We were trying to go have dinner in Little Italy, and they were worried we weren’t going to make it downtown! I don’t think it was that dangerous, but they did. That was my first exposure.

Sean Plottner: And Muppet Magazine was in New York, right?

David Granger: Yeah, yeah. No, I did the polishing course at Radcliffe and that was, like, an eight-week course or something, and then came down here where I thought I was going to live with this friend of mine on Long Island and commute into the city and find a job. But his mom misunderstood. He was living with his parents and his mom misunderstood when he’d asked if I could stay with him. And after, like, three days, she said, “I didn’t mean he could stay forever.”

Sean Plottner: Okay, so after you got the pink slip at Muppet Magazine, tell us where you went. Give us a quick summary of what happened after that.

David Granger: There’s no quick summary. But, luckily, our design director was a woman named Gail Sagerstrom and she had worked for Inside Sports. I don’t know if you remember that, but it was a publication backed by The Washington Post. It was a monthly magazine and it had just amazing ambitions in terms of storytelling. It was run by John A. Walsh, who had run all sorts of things. He’d been managing editor at Rolling Stone and helped create the Style section of The Washington Post, and later went on to basically run ESPN.

He created the modern Sports Center and was their creative genius for over 20 years. She said, “Oh you have to call my friend John Walsh”— she’d been his design director at Inside Sports. [So I] called him. Long story short, after several months he hired me to be his research assistant on a history—he’d been fired from his previous job and he was unemployed and had no money—and he got this gig doing a book that was a history of the Heisman Trophy.

So he hired me to be his research assistant and he promised me $1,800 if I would work with him until he completed this thing. I ended up writing about 60% of the book, and then John got stiffed on his fee from the book packager who had hired him, so he had to stiff me on his fee because he had two little kids and an apartment he couldn’t afford. And basically just promised me that he was going to be my “guardian angel.”

And my next three jobs—though all of them were relatively short-lived—came through John’s support or connections or whatever. After I worked with him, I went to work for Family Weekly magazine, which was kind of the poor man’s/poor woman’s Parade. It was the Sunday supplement for C and D counties.

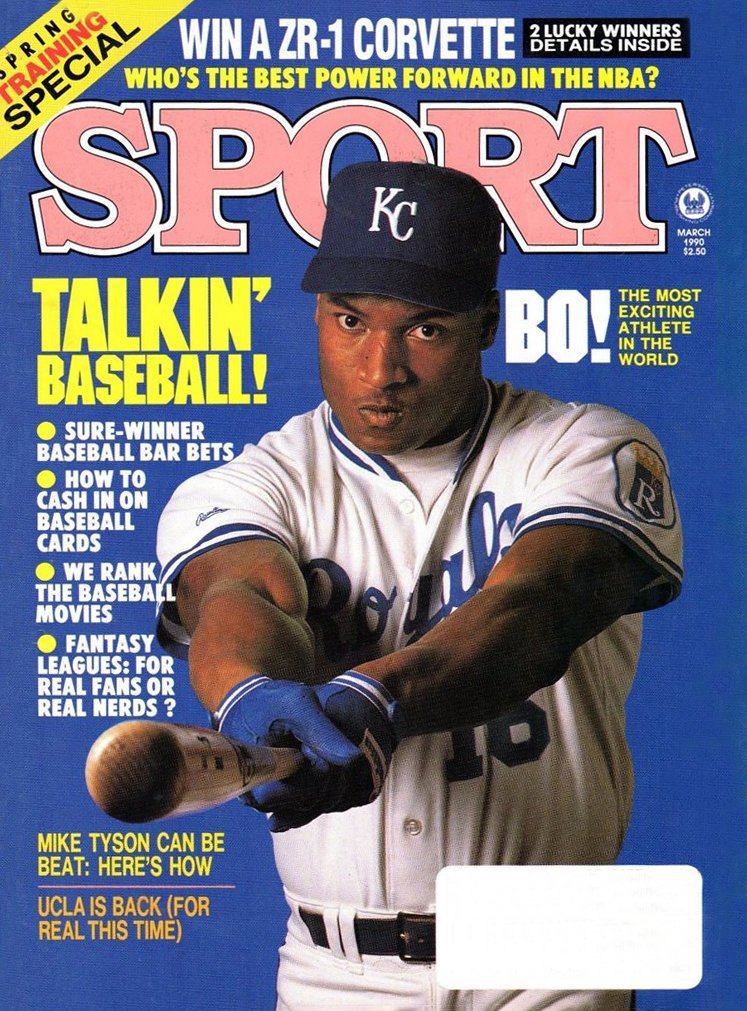

Then that went out of business, and I freelanced unsuccessfully for a little while. Very luckily, I got a job at Sport magazine, which was fantastic. It was like the lunatics were running that asylum. It was a great magazine, but the editor-in-chief was the same age I was—which was not even 30, I don’t think.

The oldest guy was Peter Griffin, who I think was 32—he later became my deputy editor at Esquire—and I had lasted there for 18 months and got lured away by this sports business magazine called Sports. Inc. It was the eighties, business was hot, sports was hot. “Let’s do a weekly sports business, trade magazine!” Which was an amazing education because you’re working with really mostly untalented people, though there were some exceptions, like Richard Sandomir, who’s still at the Times, but you’ve got to put out a magazine every week.

And I was in charge of all the writing or a lot of it, and it was stressful. You learn to rewrite really fast. I mean, you asked me about journalism school—I think I learned more in those 18 months of working on a trade magazine than ever before. You’d get a pile of shit that was supposed to be copy and you had about 12 minutes to turn it into an 800-word story.

It was a fantastic learning experience, and you learned what a story was. So that was good. And that folded right about the time Melanie and I had twins. So I had another very stressful period of freelancing, and then, I think it was through John’s intercession, I got an interview at The National Sports Daily, which you’re also familiar with.

History repeats itself

Sean Plottner: Very, yes.

David Granger: Which was an amazing enterprise to create a newspaper from scratch? A national newspaper from scratch? Who does that? And turned out to be as insane as it seemed. But [we had] almost unlimited resources, though not for people like you and me. For all the famous columnists and writers that they hired and the editors that they lured away from all of America’s great papers, it had unlimited resources.

We were more like peons, you and I. But it was a great gig, and a great, great learning experience. I got to work with Rob Fleder on all the feature stories, and then had some side gigs as well. So that lasted 18 months before that was blown up.

Sean Plottner: Let’s go back to Walsh just briefly. What a “guardian angel” to have! I had one meeting with him back in the day when I was at Disney. He was at ESPN, and what an intimidating presence in the room he was to me.

David Granger: Can I briefly tell you the story of my first meeting with John?

Sean Plottner: Go right ahead. One’s first encounter has got to be quite memorable.

David Granger: So as Gail suggested, I called John and he picked up the phone. And I explain who I am and that Gail told me to call. And he says, “Call me in a month.” And how many young people are going to do that? Actually call back in a month? But I put it in my calendar. A month later I called him and it turned out the day I first called him, he had just found out that Group W Broadcasting was not going to finance his attempt to create a competitor to ESPN. He’d been working on that for months. And so I happened to call him at a bad time.

So I call him a month later and he says, “Okay, meet me for drinks on Friday, five o’clock, The Oak Room bar at The Plaza.”

I go, “Well, how will I recognize you?”

He goes, “I’ll be in a brown sports car.”

I’m like, “What?”

So I go to The Oak Room. I get a table near a window so I can look out on Park Avenue South for a brown sports car to drive up. I’m there for half an hour nursing a beer because you know, I was unemployed. I think I had $11 to get me through the weekend. And I’m nursing a beer. Nursing. Nursing. I hear the bartender scream out, “David Granger? Is there a David Granger in the house?” I raise my hand. This albino walks over to the table, and he says, “Let’s get away from this window.”

So we go back into a darkened corner of the bar. There’s a candle on the table and he immediately blows out the candle, and he starts talking. He starts asking me questions about myself, but he won’t look at me. You know, I’m thinking, “This guy hates me!” Turns out, albinos, most of them, light really irritates their eyes.

He listens to me for a while and he says, “Okay, I might have something for you.” Meanwhile, I’m still nursing my beer. He’s had 1, 2, 3, 4 vodkas and I’m stressing. I have $11! This is before I ever qualified for a credit card. I didn’t have an ATM card. I just had $11. And he calls for the check. I said, “No, no, I, I’ll get this.” Because, you know, that’s what you’re supposed to do when somebody’s doing you a favor.

And he goes, “How much do you make?”

And I said, “Before I got fired, I was making $11,000.”

And he goes, “Nobody who makes $11,000 is buying me a drink.”

I was like, “Thank you, Lord. Thank you, Jesus.”

And that was my first encounter with John A. Walsh. The great John A. Walsh.

“Cathie [Black] says to everybody, ‘You guys can go. David, would you stay for a minute?’ And they pick up the Fred Rogers cover and they go, ‘What the fuck are you doing?‘”

Sean Plottner: So then you go from the sports weekly—an insane situation—to a daily. That was very exciting, as one who was part of it, and a little insane, too. What’d you do there? What’d you do at The National?

David Granger: Well, Rob Fleder and I—Rob was my boss—were tasked with creating and publishing a magazine-style feature-length story every day that The National published, which I believe was five days a week.

Sean Plottner: Yes indeed.

David Granger: Or was it six? I can’t remember.

Sean Plottner: I think it started at six and we went to five.

David Granger: Yeah, went to five. So anyway, we were supposed to do five, 5,000-word feature stories every week. And we had a staff of four—four writers and me and Rob. And then of course, Frank DeFord said, “And you can use any of the writers out in the newsroom. They’re all going to want to work for you.”

I think Ed Hinton was the only one who really wanted to work for us. So then Rob put a calendar on the wall—it was the next 12 months—and he just said, “Okay, those are the spaces we have to fill in with stories.” And it was hard. It was daunting. And we had no real freelance budget.

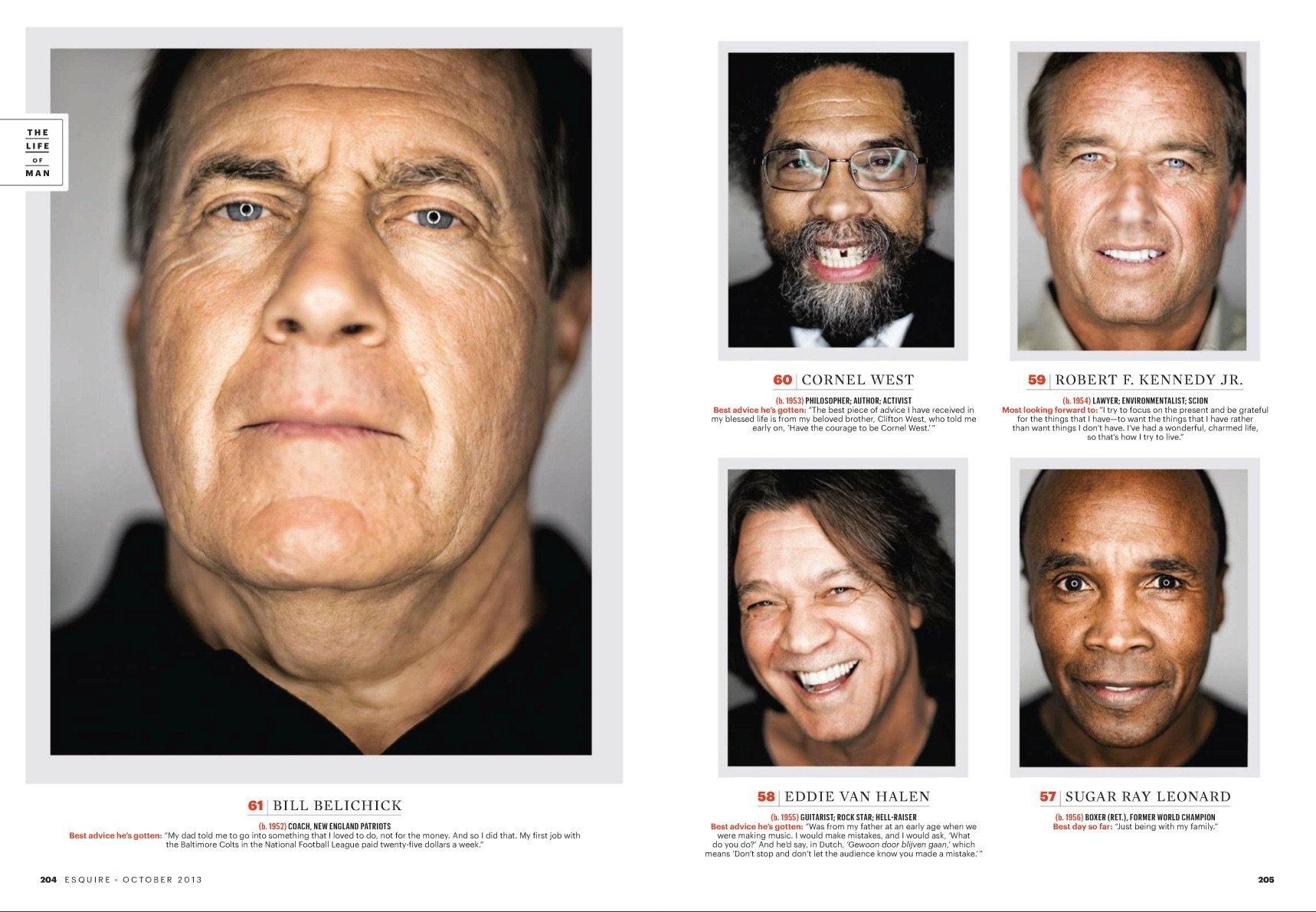

It was, use our four guys—well three guys and a woman: Johnette Howard, Charlie Pierce, Peter Richmond, and Ian Thompson—and just get them on the road. And in the 18 months that we were in business. Charlie did, if I remember right, I think 49 5,000-word feature stories. And that included travel and research writing.

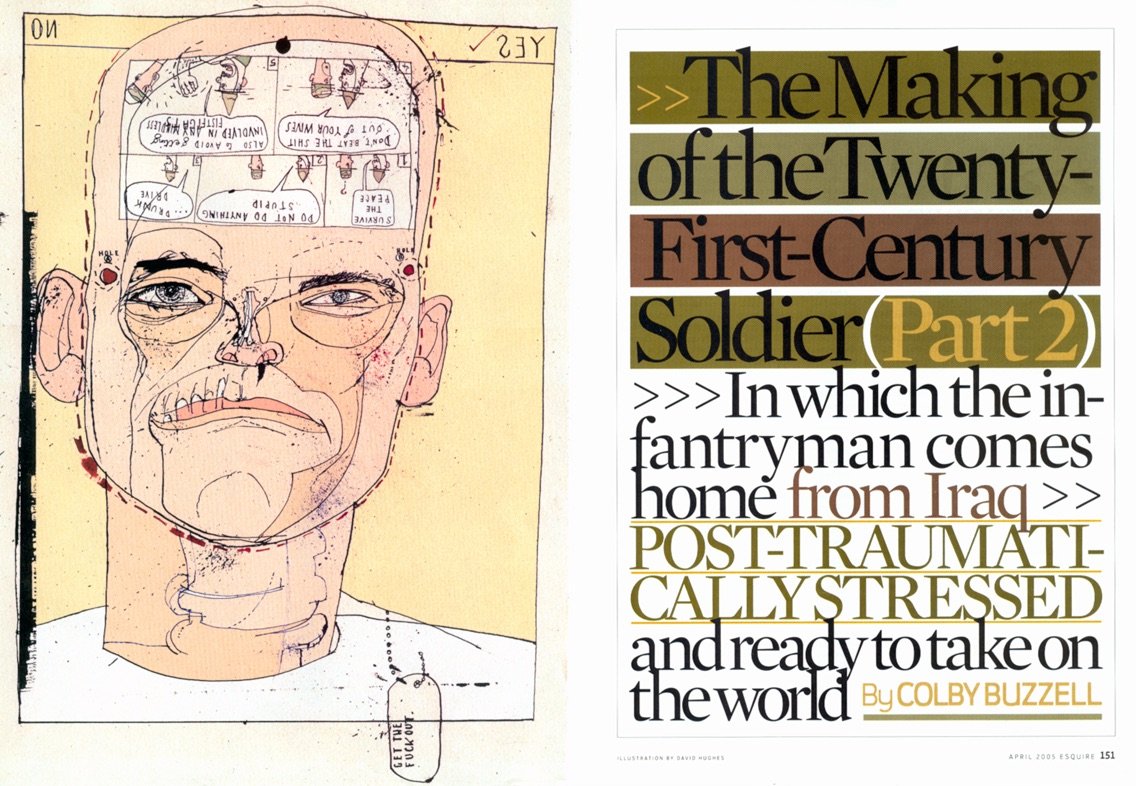

Peter Richmond was just behind him with like 47 or 48, and the other two did an equal number. And then we just begged among the writers on staff to fill in the holes. And it was a lot of work, but it was fantastic. And what an education! You got to work with amazing writers on ambitious stories.

And Rob had been a longtime editor at Sports Illustrated, a features editor, great editor. I’d learned so much from him. And it was great. And the most exciting part of that was that we were like the little magazine corner of The National.

But The National was a newspaper. And it was run by newspaper guys. And, especially guys like Van McKenzie, did not understand why Frank was wasting those four-to-six pages every week on feature stories by the guys in the magazine part of it. And they were constantly trying to take, not only my territory and the paper away from us, but at one point Rob was on vacation, and Van informed me that they were taking Rob’s office away from him. And I had to call him on vacation and tell him.

And I don’t know if you remember Rob, but a great, great man. A little tightly wound.

The first and last issues of The National Sports Daily

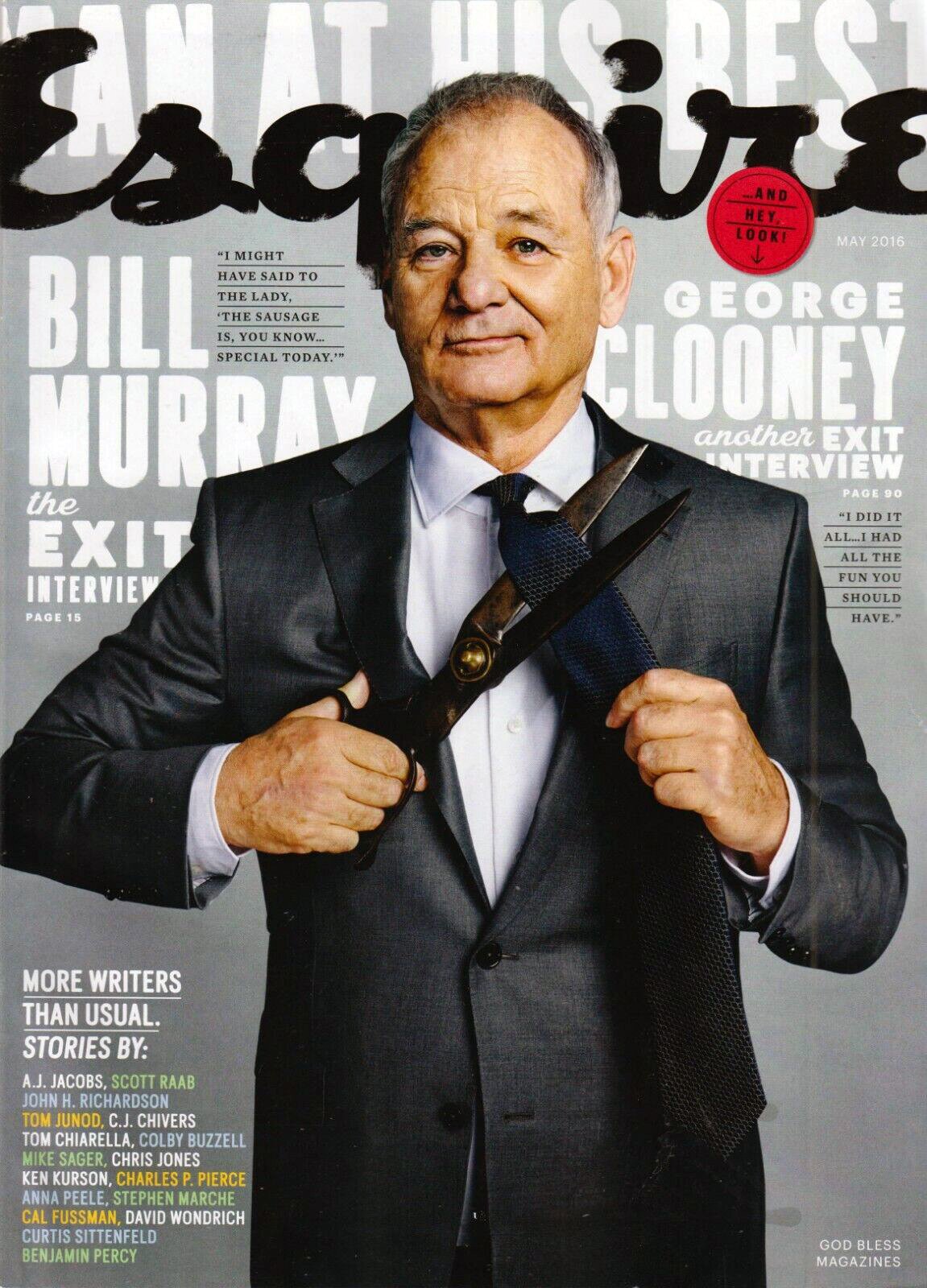

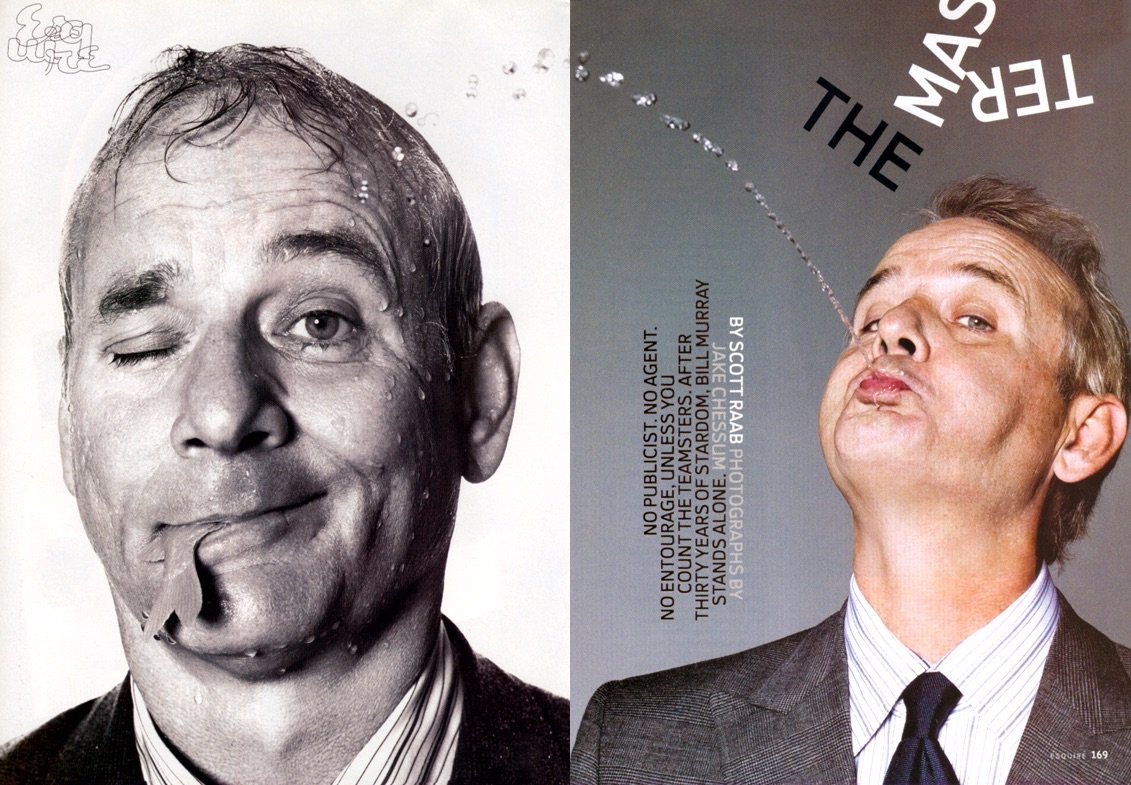

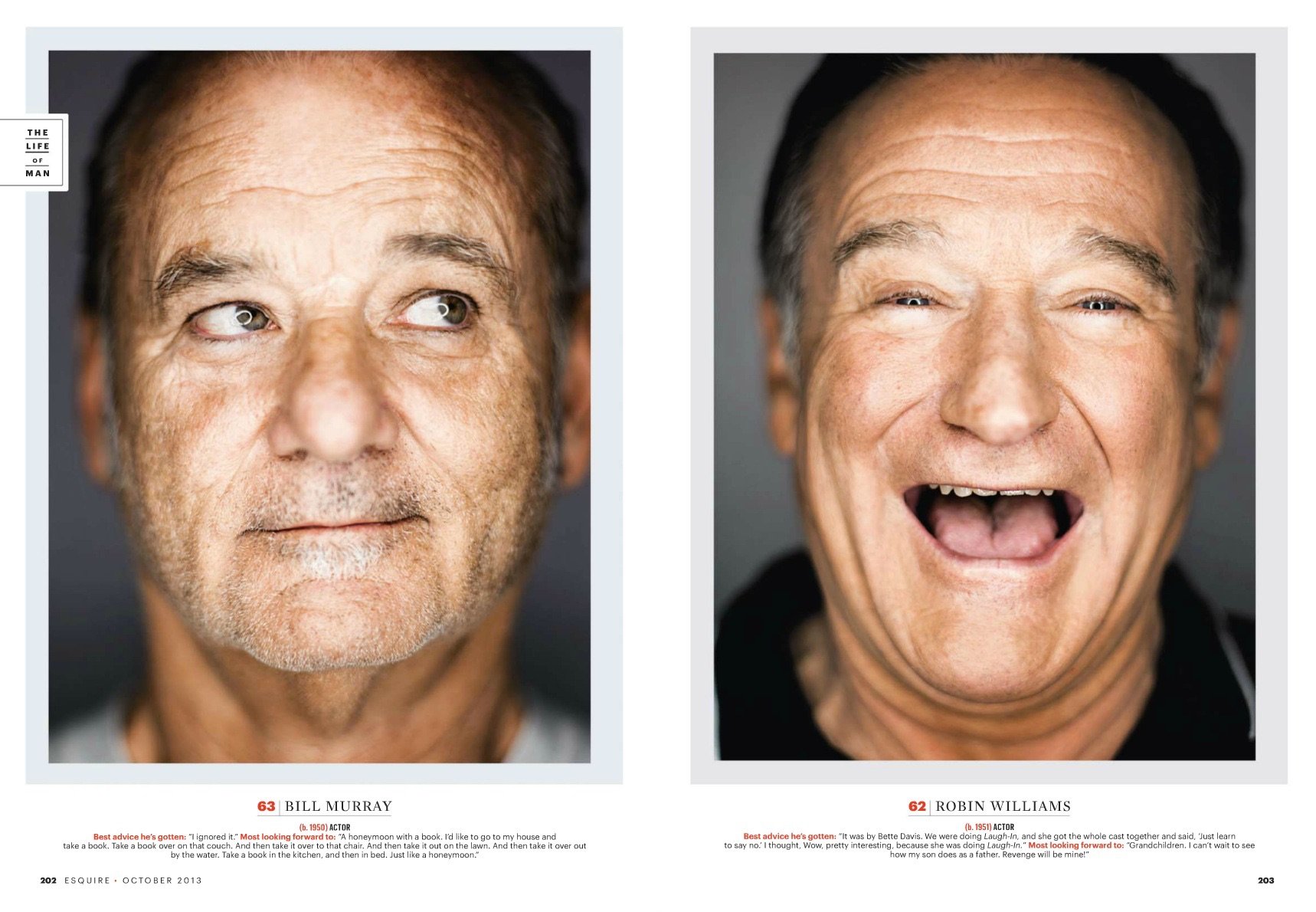

Sean Plottner: Yeah, just a bit. Sure. Well, those stories were—that section that made it just much more than a daily paper, I thought, really balanced out the publication and gave some depth to what was otherwise, a publication full of news and all kinds of small entry points and columns. Lots of voices. And enabled the paper to do some interesting cover stories. Were you involved with the Bill Murray story?

David Granger: Not directly. That was Peter Richmond’s idea. He was on our staff and I think Rob must have edited it. I did not have any involvement in it, but I just remember when Peter went to Chicago and attended a game or something with Bill. But I didn’t edit that story. Why do you ask?

Sean Plottner: The reason I ask is because I know you ended up working with Murray at Esquire and he appeared in those pages on occasion, and I’ll never forget—there were so many memorable days and events in that short-lived National—but the day Bill Murray came to the office and just started cracking on everybody, walking around. It was like—he had no handler, no leash. He just showed up in the newsroom and went wild. Were you there that day?

David Granger: I was not there that day. I heard about it. I got to be friendly with Bill during my time at Esquire and he’s never had a handler. Bill just walks through the world. You know, he told me the last time I had a significant sit down with him he just said, “I don’t worry. I just, things will be okay.” And that’s the way he walks through the world.

Sean Plottner: Speaking of worry, I recall lots of pronouncements that The National was about to go under and. Then after The Wall Street Journal finally did a story that said it looked like we’re in pretty good shape, we went under just a few months after. How did you react to that? That kind of came out of the blue for all of us, I think.

David Granger: Yeah. My main concern was what I was going to do. Like I said, when I lost one job, it was when my wife and I just had twin daughters. And when I lost The National job, we had just bought our first house in Westchester and moved my family up there.

So it was a little daunting. And Melanie, who was a librarian at NYU had firm plans to leave that job. So we were faced with the prospect of no income. But these things always work out. A little stress, you know, but I was in mourning for losing The National because it was a great gig and I worked with great people. But at that point it was just, “I’ve got to find work.” And my friend Craig Reiss had just been named the editor of Adweek, and Mediaweek, and Brandweek, and he asked me to come be his number two and essentially run all the features in those magazines. And I did that.

And the first day I was in the office, I remember looking out to this newsroom and realizing that, once again, I was at a trade magazine where there was very little talent and I had to put out not one, but three magazines a week. And I thought my chest was going to explode. But blessedly, on the second day I was there, I got a phone call from a guy at Condé Nast named Art Cooper, the editor of GQ, who said, “Everybody tells me I need to hire you.”

“I learned more working on a trade magazine than ever before. You’d get a pile of shit that was supposed to be copy and you had about 12 minutes to turn it into an 800-word story. It was a fantastic learning experience. [I] learned what a story was.”

Sean Plottner: Wow, that’s a great call to get out of the blue. Had you ever met him?

David Granger: Never met him. And it was again, John A. Walsh, Frank DeFord, and the guy whose job he was sort of trying to fill, Eliot Kaplan— all of them had said, “You’ve got to talk to David Granger.” Because, I guess, at The National I’d shown that I could do some feature stuff and all that. So I think that was day two at Adweek. And it took me over a month to convince Art that I was, I actually was the right guy to hire.

And then he offered me $15,000 less than I was making, just as a test to see how much I wanted to work for GQ. And eventually I bailed on my friend Craig and joined the glossy magazine world.

Sean Plottner: And not without first helping a few refugees from The National come aboard over at Adweek-Mediaweek, like yours truly. And, uh, let’s give a shout out to Scott Robson. I haven’t even heard that name in many, many years, but, and I do think that between the time you called me and I got there, you were out of there.

David Granger: Yeah, as I said, it was my second day when I got the call from Art and I think I was gone in just about a month from that day. So I’m sorry to abandon you.

Sean Plottner: Well, it worked out fine. And, okay, so at GQ, I believe you were executive editor” Art’s number two?

David Granger: No, no, no. I was never number two. The title was, like, assistant managing editor. There was Art, and then there was Marty Beiser, who was, like, whatever the number two was, and then Lisa Hintelmann, and then a few assistant managing editors, two or three assistant managing editors, and I was one of those. I wasn’t the top guy. Late in my time there, I think Art sort of saw me as his protégé. But I never had the official title of protégé.

Granger’s early Esquire work

Sean Plottner: Okay, so then let’s get to Esquire. You apparently wrote a letter to Cathie Black.

David Granger: Yeah, I’d been at GQ for five-plus years. I mean, a great opportunity. I got to work with all these amazing writers that I brought into the magazine, but I was eager to try to run my own show and I kept auditioning for editor-in-chief jobs.

Internally I was considered for the Details job, which went to Michael Caruso. I auditioned for a couple of those, including the top job at Civilization, the magazine of the Library of Congress. And my advice to them was they should stop using both the words “library” and “congress” if they were going to have a successful magazine. I don’t think I was offered that job.

But all this time I’d been thinking about Esquire, longing for Esquire. It’d been my first magazine as a man, and I’d kept a very close eye on it. And it was dying when I was at GQ. I mean, GQ was kicking its ass, especially in terms of fashion advertising.

Men’s Health had come on the scene and was kicking its ass in terms of a lot of the lifestyle stuff and active living stuff. It was dying. And it was also badly run. It was not a good magazine. It was very New York-centric. It looked down its nose at its readers. And I read this story on the front page of the business section of The New York Times, about the then-editor of Esquire, and the first sentence was, “Ed Kosner is going to miss this office.”

And it was basically prophesying the departure of Ed and maybe the demise of Esquire. And I’d been watching and longing for Esquire, but that kind of kickstarted me. And I started writing this letter to Cathie Black, who’d just recently become the new president of Hearst Magazines, explaining that I knew three things that none of the previous three editors of Esquire had been aware of. And that those three things were a formula for Esquire’s success.

And so I wrote this letter and just agonized over it. And I was so freaked out about how to get it to her. I didn’t want to give it to the messenger service at Condé Nast, because you know, who knows what happens to it. So I walked it over to the address on the masthead of Esquire. And I just assumed that’s where Hearst was. Of course, they were in a separate building, so I left it with the guys at the desk down there, and only later realized it was the wrong building. Went back and grabbed it from them and took it over to the main tower and left it with someone who eventually got her to Cathie.

And then a couple days later, I started calling her. I just started calling her number and her secretary would say that she’d get back to me. She never did. I’d call again, I’d call again, I’d call again. Finally, at some point she picked up and I said, “Oh, hey, it’s uh, David Granger, I’m an editor at GQ. I wrote you a letter about Esquire. I was just wondering if you’d be interested in talking with me?”

And there was this pause, this long pause. And then she said, “Not really.”

“Nobody who makes $11,000 is buying me a drink.”

Sean Plottner: Oh! Roasted!

David Granger: And then she went on to say that she was very supportive of all their editors and there are no plans for any changes and blah, blah, blah. So I was devastated because I was on the verge of turning 40 and I figured either the magazine was going to go out of business or somebody else would get it. And by the time that person failed, I’d be too old to get the magazine. I had all those thoughts.

But there was no way for me to make another approach. And, like, a year later, this guy started calling my office. Ed Kosner got fired and some guy named Michael Wolf kept calling my office. He wasn’t the media guy. He was a consultant who worked for Booz Allen Hamilton, and I didn’t know who he was, so I kept telling my assistant to take a message.

He called like five times. Then it was 5:30. My assistant was gone, and the phone rings. I pick it up and he says, “Oh, it’s Michael Wolf.”

And I said, “Oh, I’m so sorry I didn’t get back to you. How can I help you?”

He said, “I was just wondering if you wanted to have lunch with Cathie Black tomorrow.”

I was like, “I’m really sorry I didn’t get back to you!”

And the next day I had lunch with Cathie. And it was one of the most intimidating lunches I’ve ever had. It was in the corporate dining room at Hearst, and there was a guy with a thing in his ear and I thought he was, like, security or something. Turns out he was just the guy who ran the dining room. I was intimidated! And we go in and we sit at William Randolph Hearst’s boardroom table on the corner, with waiters and all this kind of stuff. And it was fantastic conversation, like an hour and a half. Really intense.

But at the end of it she said, “Well, do you have any thoughts?”

And I said, “Yeah, I’m just glad I wrote you that letter.”

And it was clear to me she had no idea what I was talking about.

Sean Plottner: Wow. Those three things didn’t matter. Whatever they were.

David Granger: I don’t remember what they were, but they found the letter later and it became part of their PR that I had had the gumption to write this letter.

Sean Plottner: Yep. Yep. It’s a rags-to-riches story. So you get to Esquire, you’ve got the job. Pretty exciting I would imagine.

David Granger: Yeah, it was my life, man. I was 40 years old.

Sean Plottner: Well, and you saw a magazine that was broken and needed to be fixed. You had a plan, you fixed it. What did you learn quickly that maybe you hadn’t been told about that job? What were the big surprises, if any?

David Granger: Before I got into that job, I knew exactly what I needed to do. Cathie had asked me to write up a plan and part of that plan was I had to write and annotate my first three tables of contents. I had to explain my cover strategy and what my first three covers would be.

All this kind of stuff I knew exactly what to do. But you get in there and you start having meetings with circulation people and ad salespeople, and they all know exactly what you’re supposed to do. And it’s not anything like what your idea was. You know? It’s like they know because all these things have been tried over and over again for 60, 70, a hundred years.

They know exactly what doesn’t work. They just have no freaking idea what does work. But the thing that any young editor is going to be faced with is that everybody second guesses you. You have two issues when they go, “Oh, that’s interesting. And that’s interesting.” And then on the third issue, it’s pure second guessing. Every meeting is called to tell you what you’re doing wrong.

And that’s the thing you don’t understand. You think you’re going to get a long runway. And you get to execute. And really for the first couple issues, the cupboards were bare, man. There was not a single story! We were supposed to be putting out the fashion issue. There hadn’t been a single fashion portfolio shot. There was not a cover planned. And we had, like, four weeks to get that issue closed. We had to beg, borrow, and steal.

So any thought you have that you’re going to plan anything is—and then of course, I fired everybody the first day I got there. And so I had like four people helping me try to put out a magazine in four weeks.

And so it’s just pure panic. And then you’re getting second-guessed every day of your life. So it takes a while and you have to be under the threat of being fired, before you just decide, “I’m going to do what I’m proud of because I’m going to get fired anyway.”

But, luckily, I made a couple of good hires. I hired Peter Griffin, who is the smartest man alive, the best editor I’ve ever worked with, and he agreed to come on on a temporary basis. And then I hired writers, basically all of whom moved over from GQ to Esquire. So I had a core group of people that I could bounce stuff off of. And then Lisa Hintelmann came over from GQ and I finally got Helene Rubinstein, who was at another Condé Nast magazine, to come over.

And we assembled a little core of a support group and things started to happen. But it was like three years before anything good really happened. And I’ve got to tell you, I guess there was a little bit of patience, but that patience ran out by the time of my second budget meeting. My first budget meeting—I got the job in June and the budget season always starts in September. So a year from that first September, I’d done 15 issues and we’d done a couple questionable covers. But the cover that was on the budget book was my Mr. Rogers cover. It was like Fred Rogers. This was a long time ago. And it was shot by Dan Winters. So it was an eccentric photo. And it was Mr. Rogers. I mean, it was Mr. Rogers.

It was the Heroes Issue. And it was a really good issue. But we got into that budget meeting, and we go through it, and everything’s fine. And Cathie says to my publisher and everybody else, “Valerie, you guys can go. David, would you stay for a minute?” And she and her number two, Mark Miller, are sitting there and they pick up the Fred Rogers cover and they go, “What the fuck are you doing?”

Sean Plottner: Wow. Welcome to the neighborhood.

David Granger: Yeah. And that was when I realized that I was not long for Esquire magazine, but I managed at that point to kind of nut up and do the things that I really wanted to, and the things that I thought Esquire should be doing. And I got a little more time and things really started to turn around. It took two years, but things started to turn around.

“We decided to make Esquire the laboratory for trying to figure out what a magazine was capable of beyond what magazines had traditionally been capable of.”

Sean Plottner: That’s interesting about having such a detailed plan, knowing what you wanted to do. It reminds me of the old [Mike Tyson quote], “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the face.”

David Granger: That’s exactly right.

Sean Plottner: Yeah. And that’s very interesting that you had to create your own table of contents. That’s an intriguing exercise.

David Granger: That was an amazing weekend. She gave me that assignment on the Friday of Memorial Day and told me that she wanted it on Tuesday. And it wasn’t just like the TOC, it was, like, marketing plans for Esquire. It was staffing plans. It was an intense weekend. But luckily I’d been up for the Details job, I’d been up for the Civilization job, a couple others, and I had all these plans I’d written up for those people.

So I scavenged those and then I called all my writers, took them into my confidence and begged them for ideas. It was an intense weekend. But it’s helpful to have a plan, even though pretty soon that plan’s no longer of any use.

Sean Plottner: Yeah. The punch in the face. You mentioned Helene Rubinstein—I haven’t been shadowing you your entire career, but Helene hired me when I made my big move from Knoxville to New York. She hired me in 1989 at US Magazine.

David Granger: Wow.

Sean Plottner: I became a music editor and worked there for a year or so before I went over to The National. So, interesting how different paths have crossed. What was your favorite part of the job as editor of Esquire?

David Granger: There are a lot of things to love. I loved having access to most people that I wanted to talk to. I loved working with writers. I loved having a full-time staff of, like, 40 people, and then another 10 or 15 people who were regular contract people who came to me every day with stuff I should be reading, or stuff I should listen to, or ideas for what we should do in the magazine.

People were incredibly passionate about working in Esquire, but ultimately, I think starting in 2006, I love the fact that we just decided to make Esquire the laboratory for trying to figure out what a magazine was capable of beyond what magazines had traditionally been capable of.

And that was 2006. And that was just as everybody was saying that the internet was going to destroy all forms of print. And we just had to prove that that wasn’t true. And so we used things like the internet to drive more people to the magazine. We played with all sorts of insane technical innovations like the first magazine cover on which words and images moved.

Esquire’s 75th anniversary issue featured a groundbreaking “e-Ink” cover

“We just started playing with the physical properties of the magazine—paper and ink and words and images—and just seeing what we could do.”

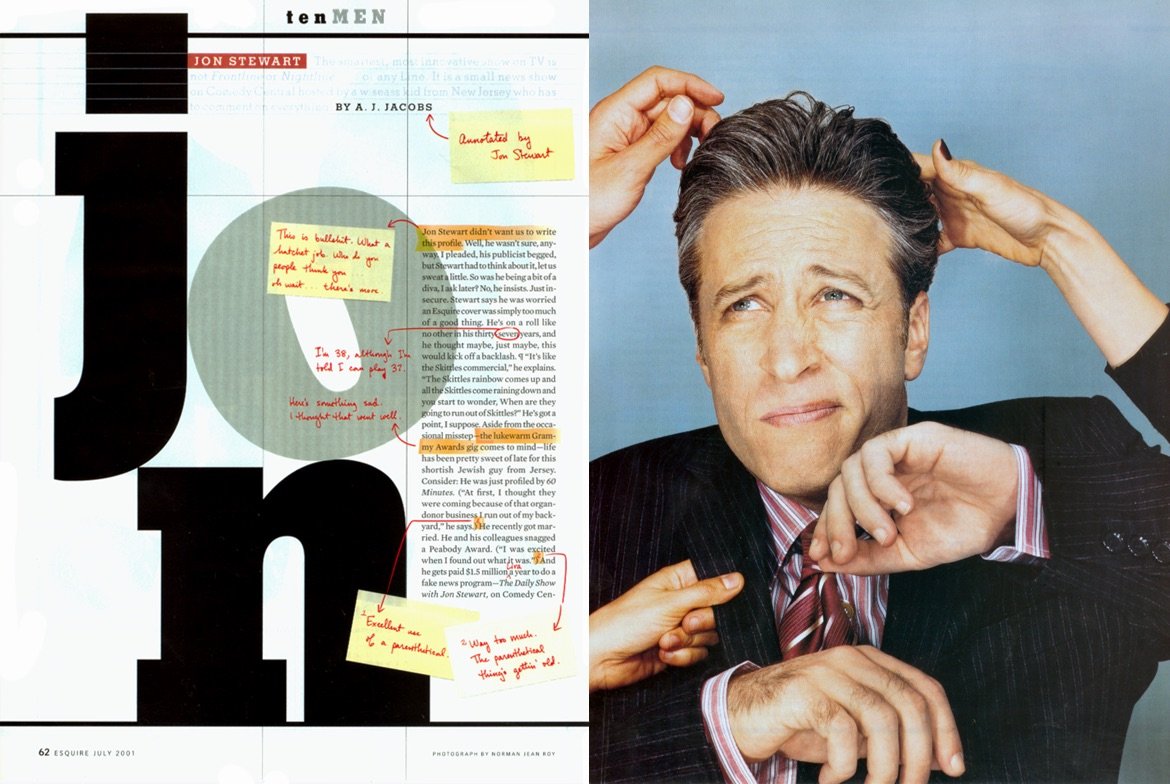

And that was in 2008. We did the first augmented reality issue of a magazine. But even more than that, we just played with what a magazine was capable of inside. We used every bit of the magazine, like nobody since Mad magazine used the margins. So we started using the margins. We published an entire short story in the bottom margin of the magazine one time.

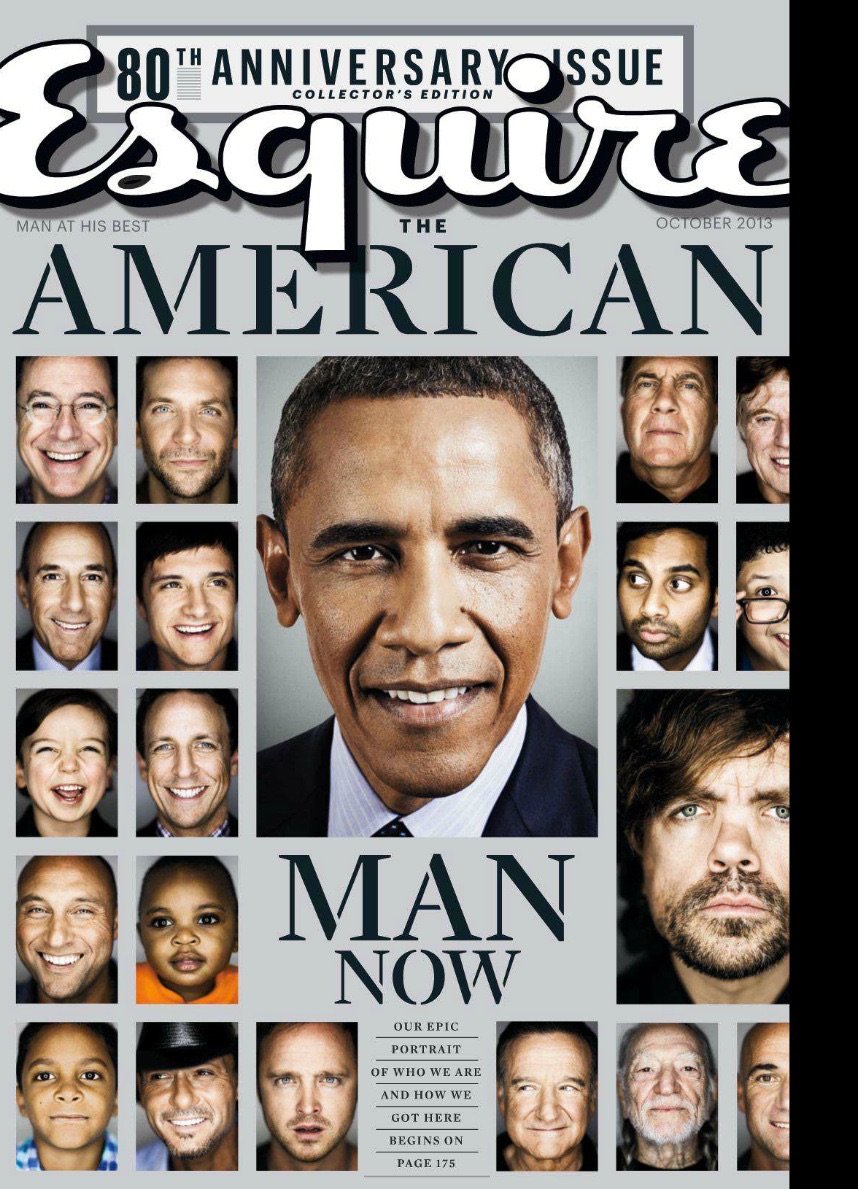

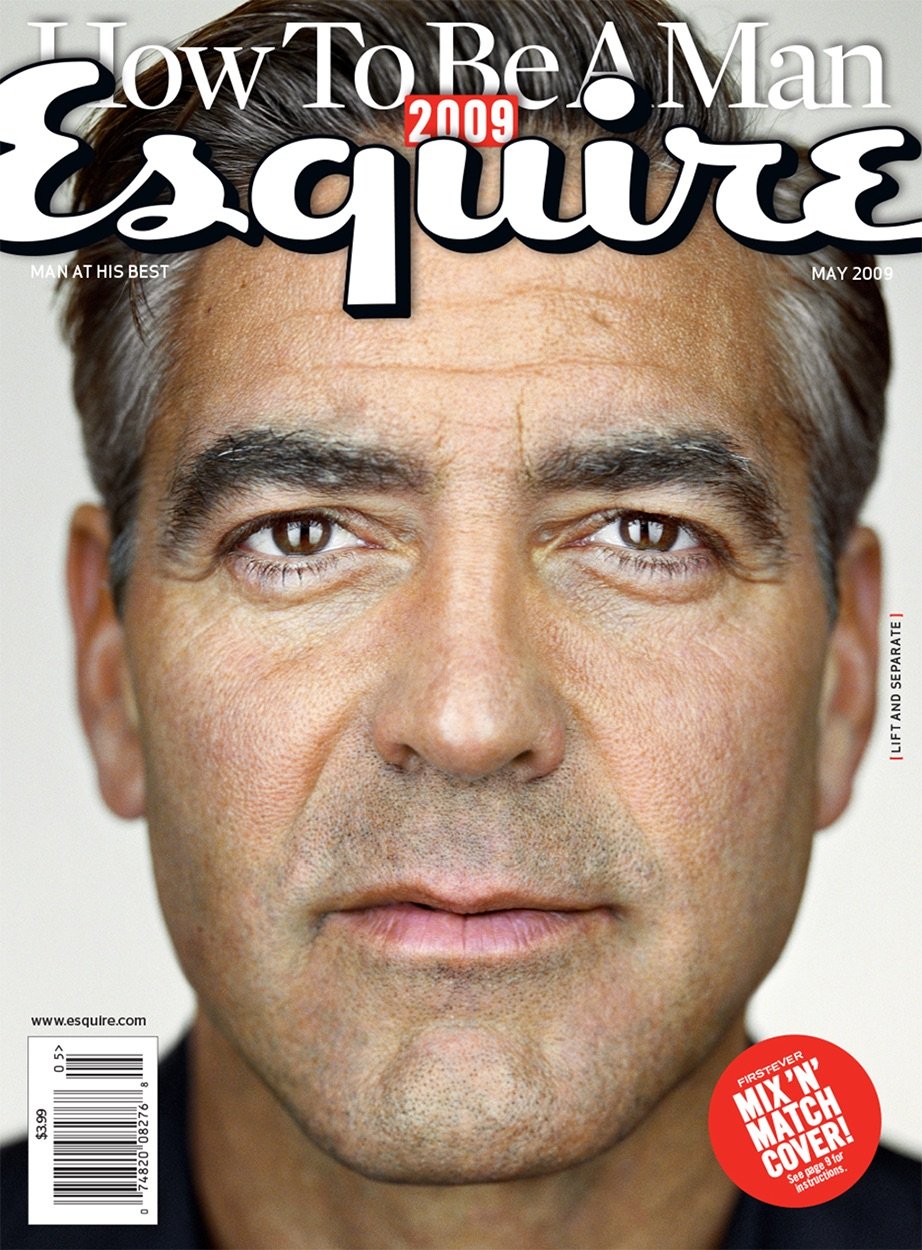

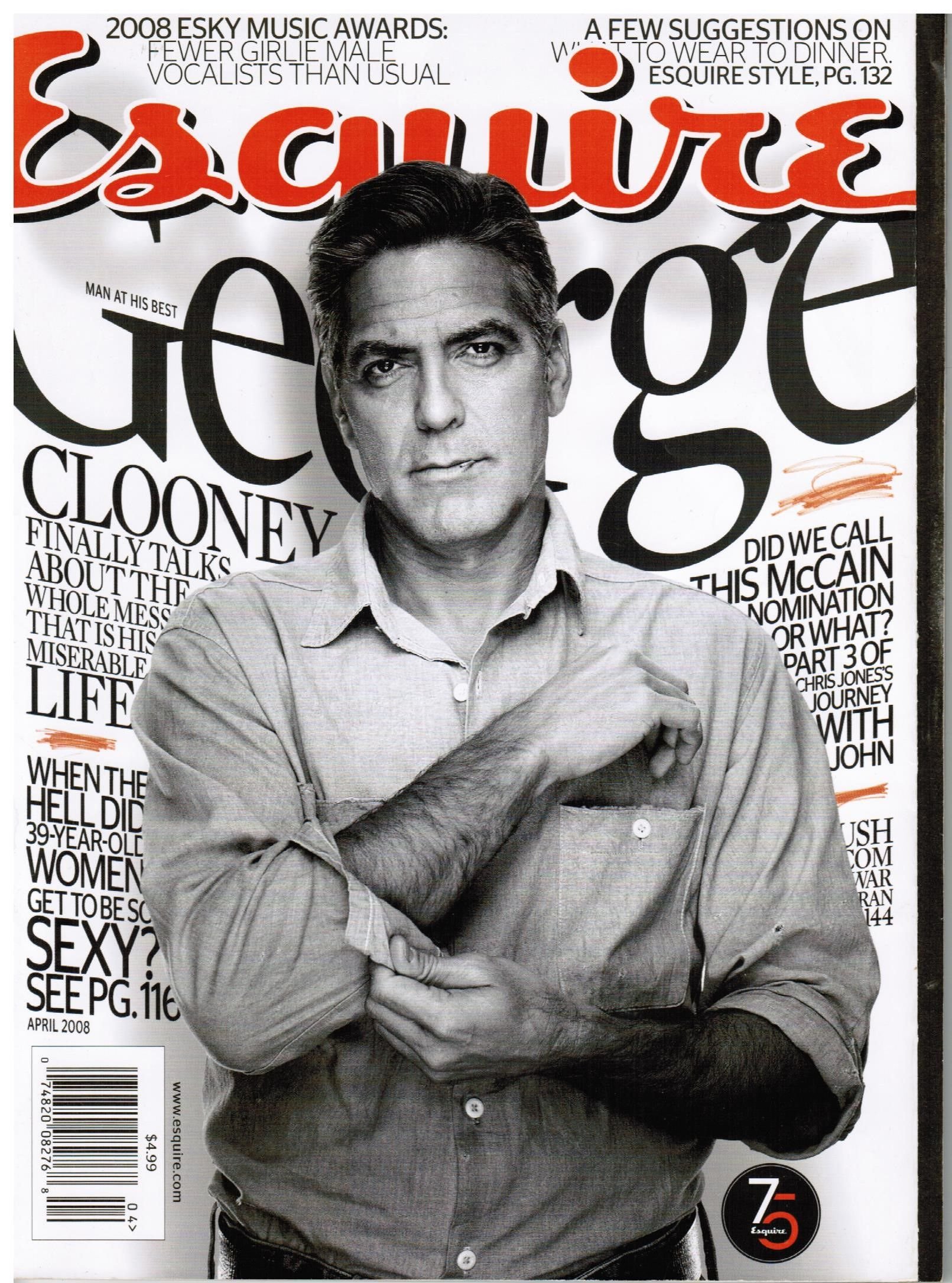

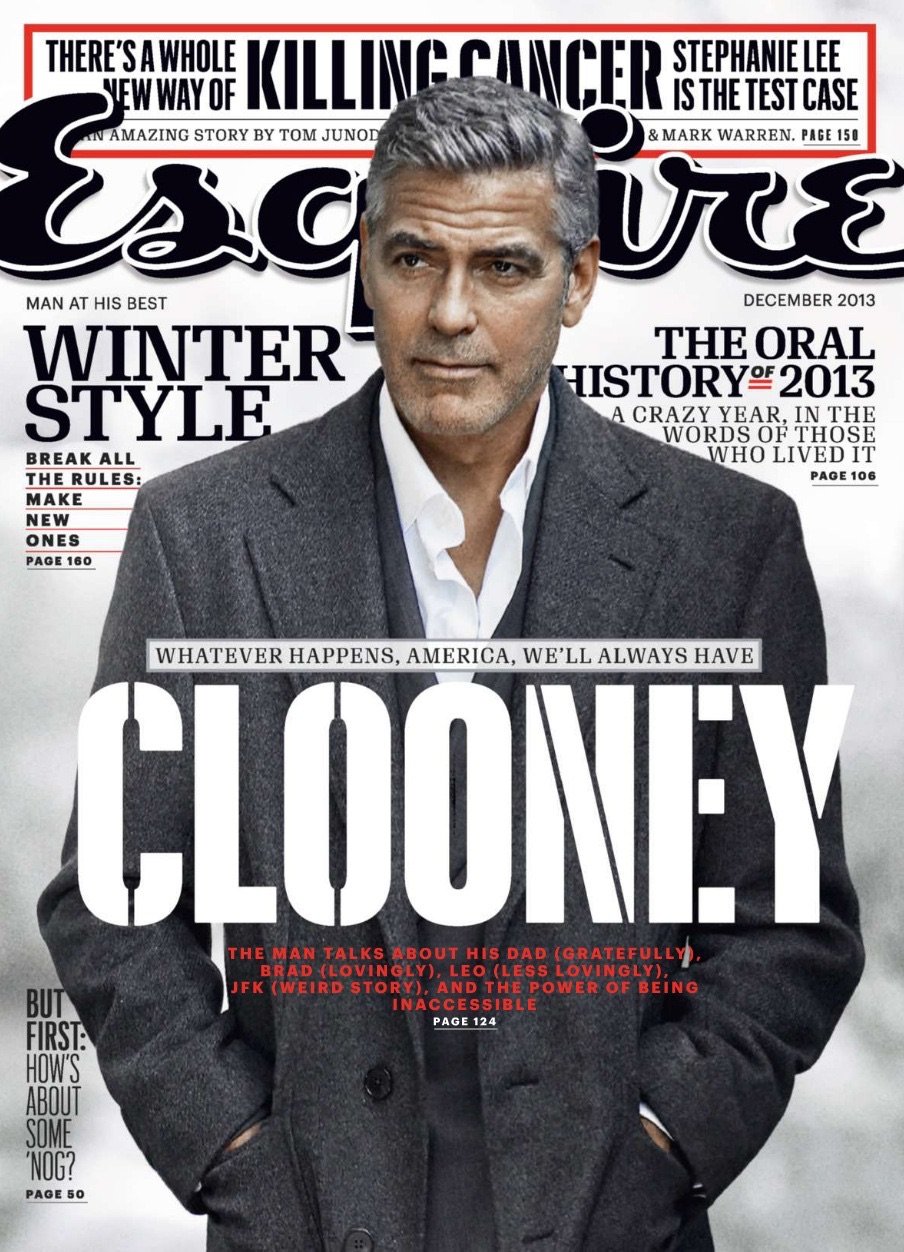

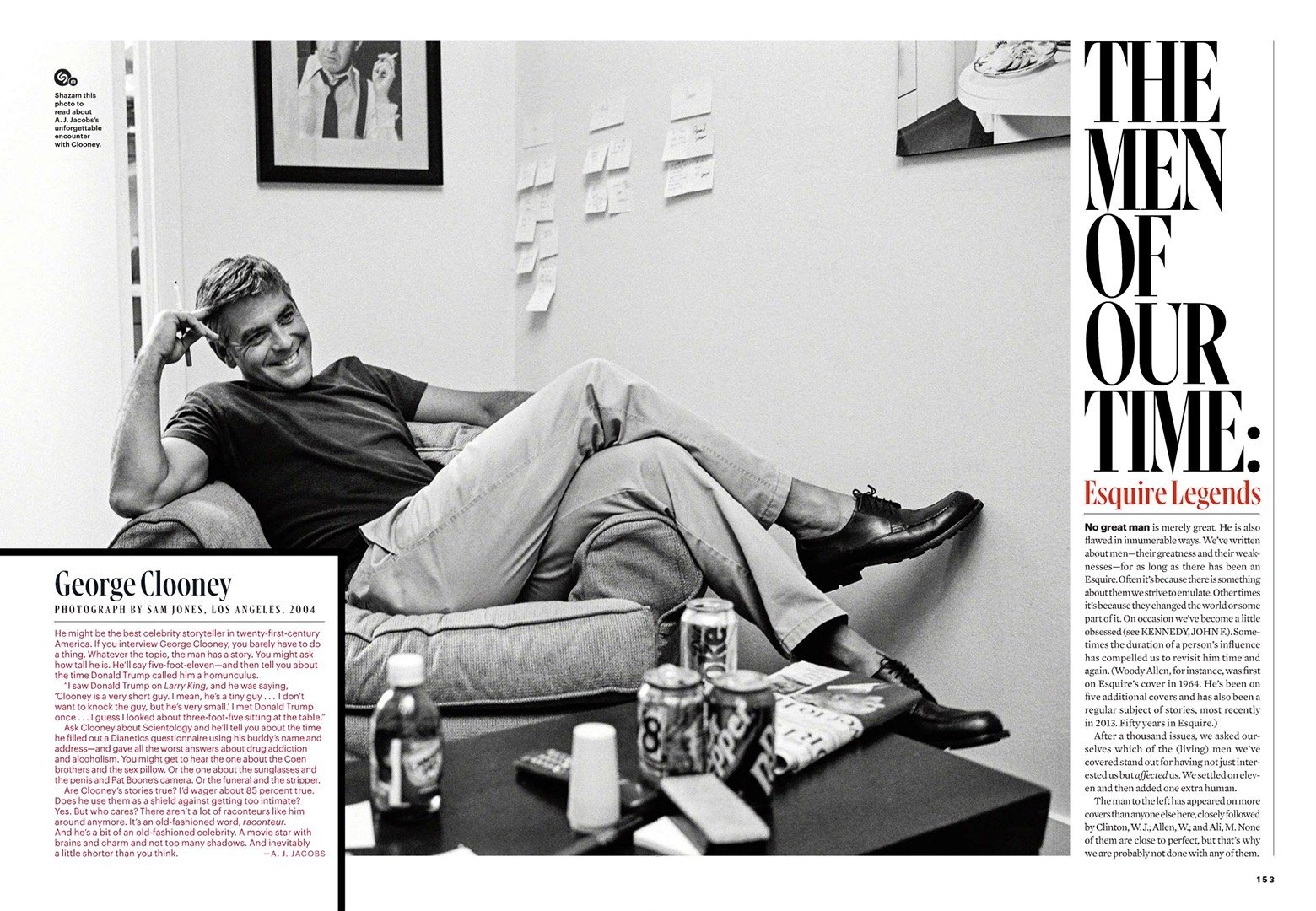

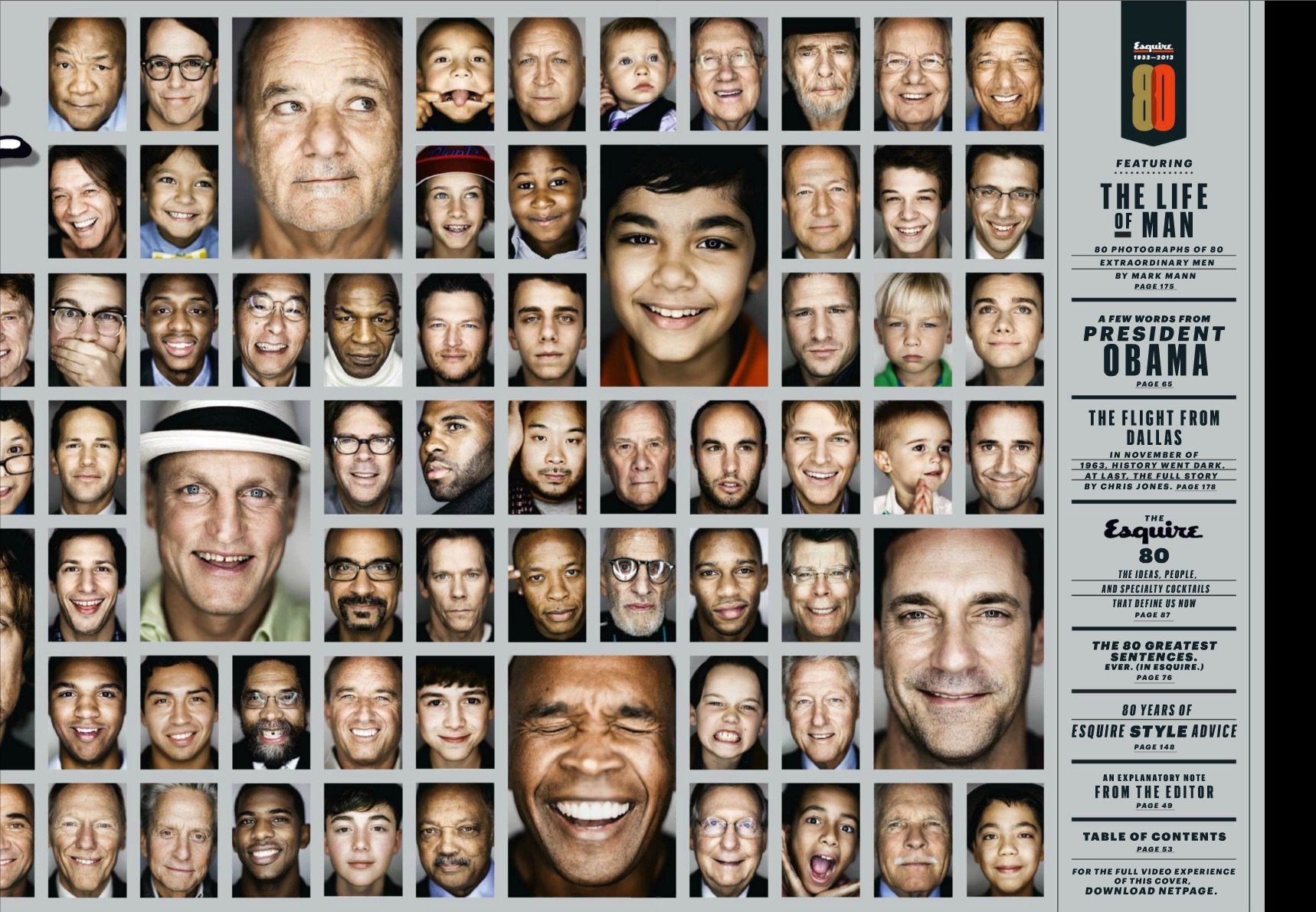

We just started playing with the physical properties of the magazine—paper and ink and words and images—and just seeing what we could do. We once did three covers on this issue about the State of the American man, and we had images, up close facial images, of Justin Timberlake, George Clooney, and Barack Obama, all shot by Martin Schoeller. And we perforated the three of them so you could just tear them apart and create 27 different faces of what the American man looked like. I mean, it was simple stuff, but nobody did it.

And we just had a billion freaking ideas. We created our own apps to turn magazine content, not web content, into something that could be shared on Twitter or emailed or texted or whatever. It was amazing the amount of video we did, especially when we had the iPad app and the iPad was going to be the “salvation of magazines.”

We did movie trailers for every issue—of a print magazine! We just had so much fun. And I think the ability to just play with possibility was the best thing about my job—and the people who helped me with it: Peter Griffin, David Curcurito, my design director, Rich Dorment, and all the young editors, Ryan [D’Agostino] and Ross [McCammon] and Tyler Cabot, and everybody.

It was just a laboratory man. It was fun.

This 2009 cover was the world’s first “augmented reality” issue. Below, an introduction to Esquire’s new iPad app.

Sean Plottner: Yeah, that’s a wonderful way of putting it: Playing with possibilities. You certainly did, it was fun, innovative. I remember your iPad app—if it was even called that when it first came out—was extremely innovative for its time. The digital cover. Very interesting and fun stuff.

How hands-on were you with copy? Writing headlines? Captions? Did you have people doing all that and you’re signing off on it? What was your role with that?

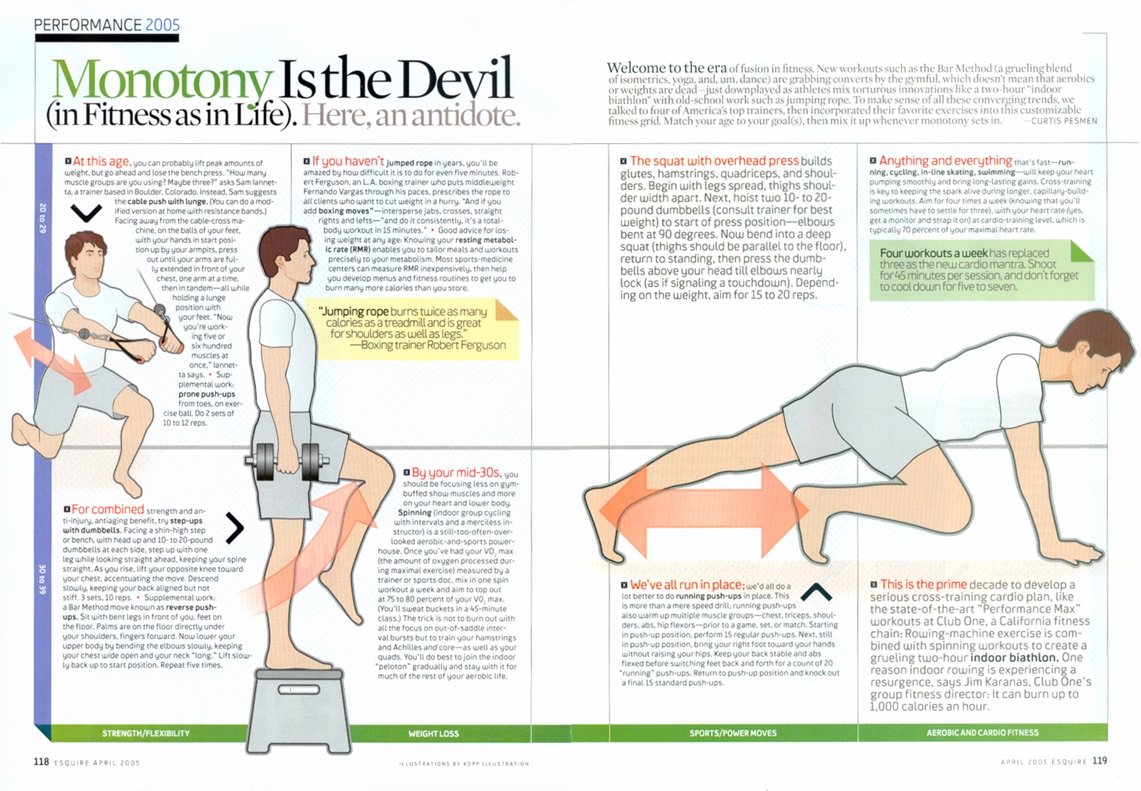

David Granger: It depends on what kind of copy. I was very hands-on with the little stuff because the little stuff is the most important stuff.

Of course, headlines and subheads are incredibly important because that determines, in a lot of cases, whether people are going to read anything. But, like, captions, and all the little tiny items that are in the front of the book, and all the marginalia we started doing. That’s the stuff that everybody’s going to read because it’s short, it’s easy.

And there was a guy who ran Entertainment Weekly named Jim Seymore—back in the nineties, I guess—and it was one of the great magazines because he demanded such excellence from all the little stuff. I remember admiring that so much. The big stuff, it’s hard in its own way, but it’s the little things that people are going to remember or they’re going to enjoy and it establishes not just a voice, but a whole environment of entertainment. You want a magazine to be an enjoyable entertainment experience and it’s those little things that do that.

When it came to feature stories, Peter Griffin and I—Peter had worked at Time Inc., and you know that was editing by committee at Time Inc. A story would go through three layers, at least, of editors before it hit the page.

And Peter and I wanted our editors to be responsible for their own stories. Their writers had to see them as the ultimate arbiters of it. That’s what we wanted. We backstopped them. Peter did an amazing job helping people with their edits on things. And I read and approved everything. And sometimes I was hands on.

By the end I was only editing one or two writers full-time. But I read everything and, if necessary, I would try to help. But yeah, I was pretty hands-on on everything. Especially anything that was display. Like working on covers? Best day of the month. Me and Curcurito and Griffin would sit in Curc’s office, order lunch, and sometimes that day would stretch into three or four days.

But those were the funnest days ever. Especially because covers always suck. They suck and they suck and they suck, until they don’t. You know? At some point they stop sucking.

“We just loaded it up. The type became the point of the cover. It was like, ‘This is a magazine of ideas and words. Let’s show that on the cover.’”

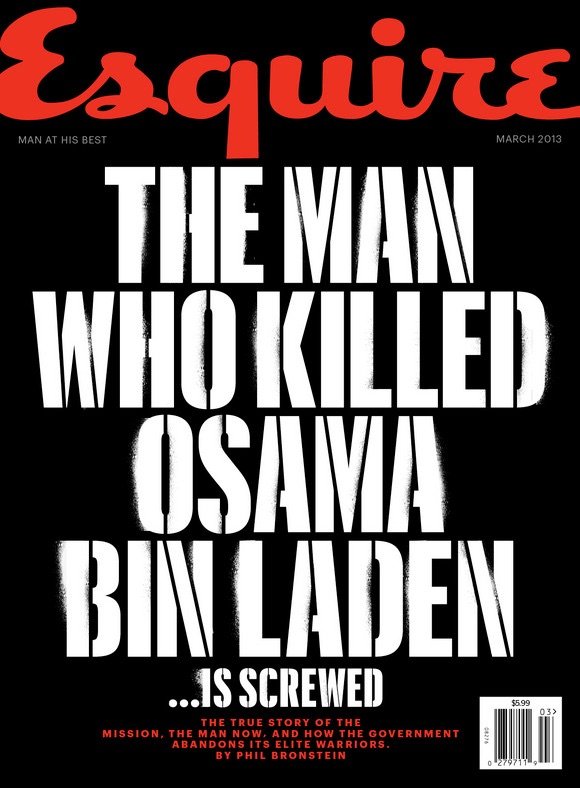

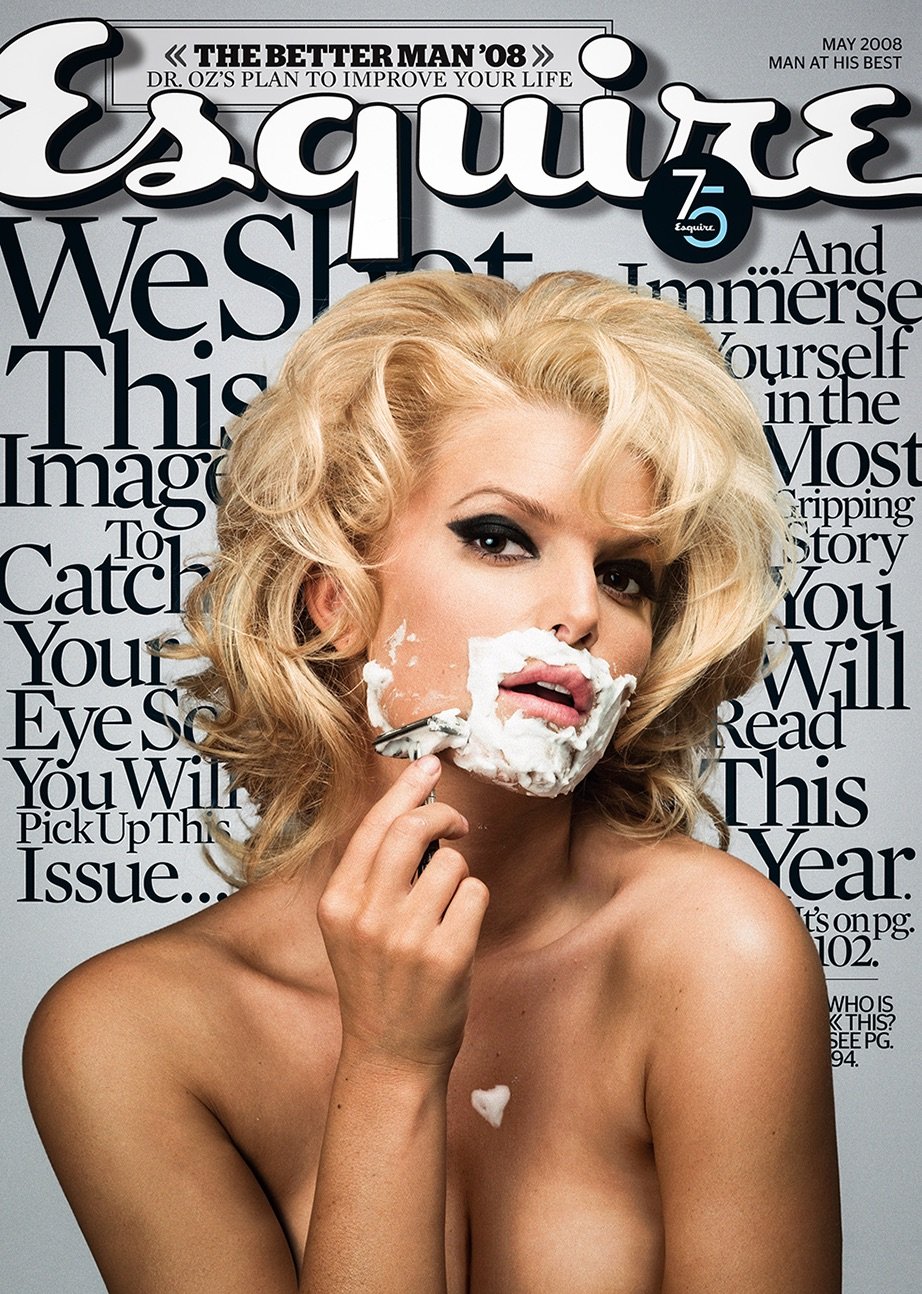

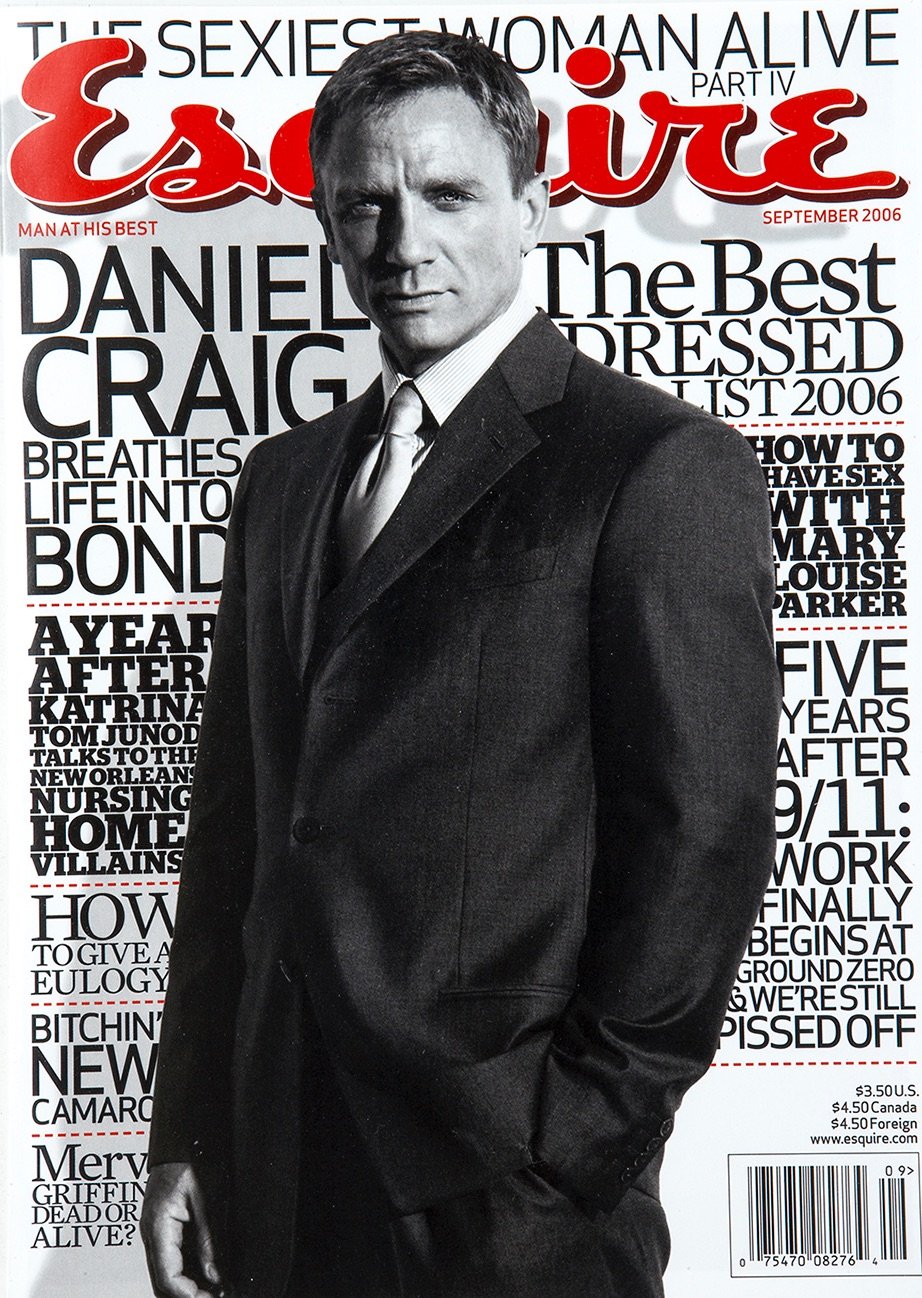

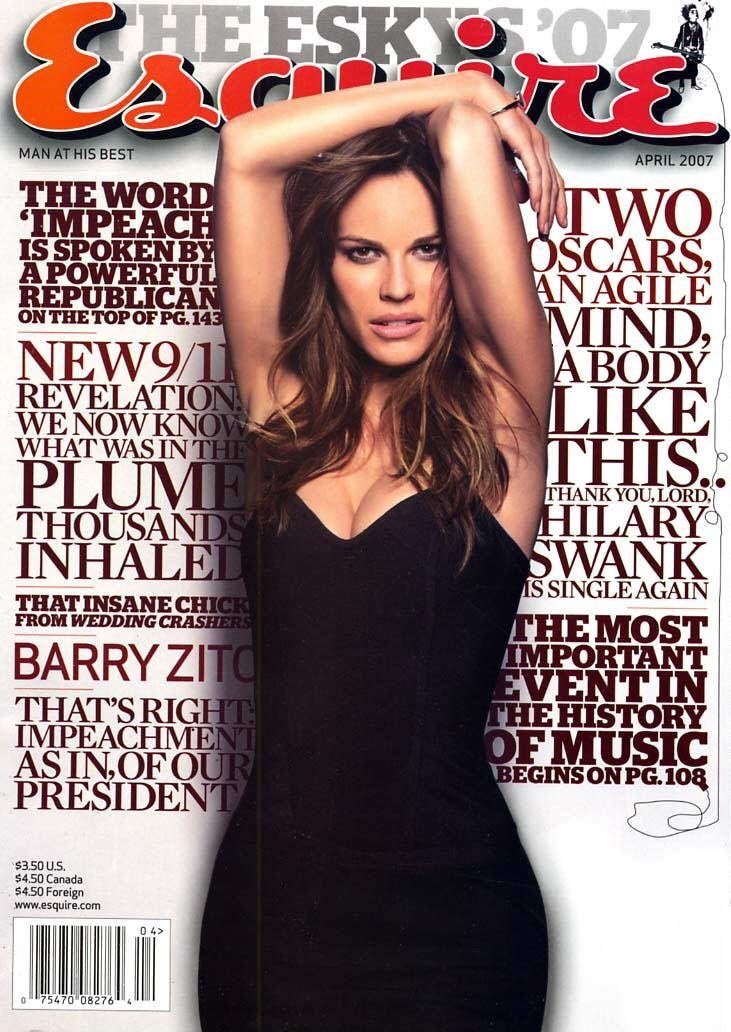

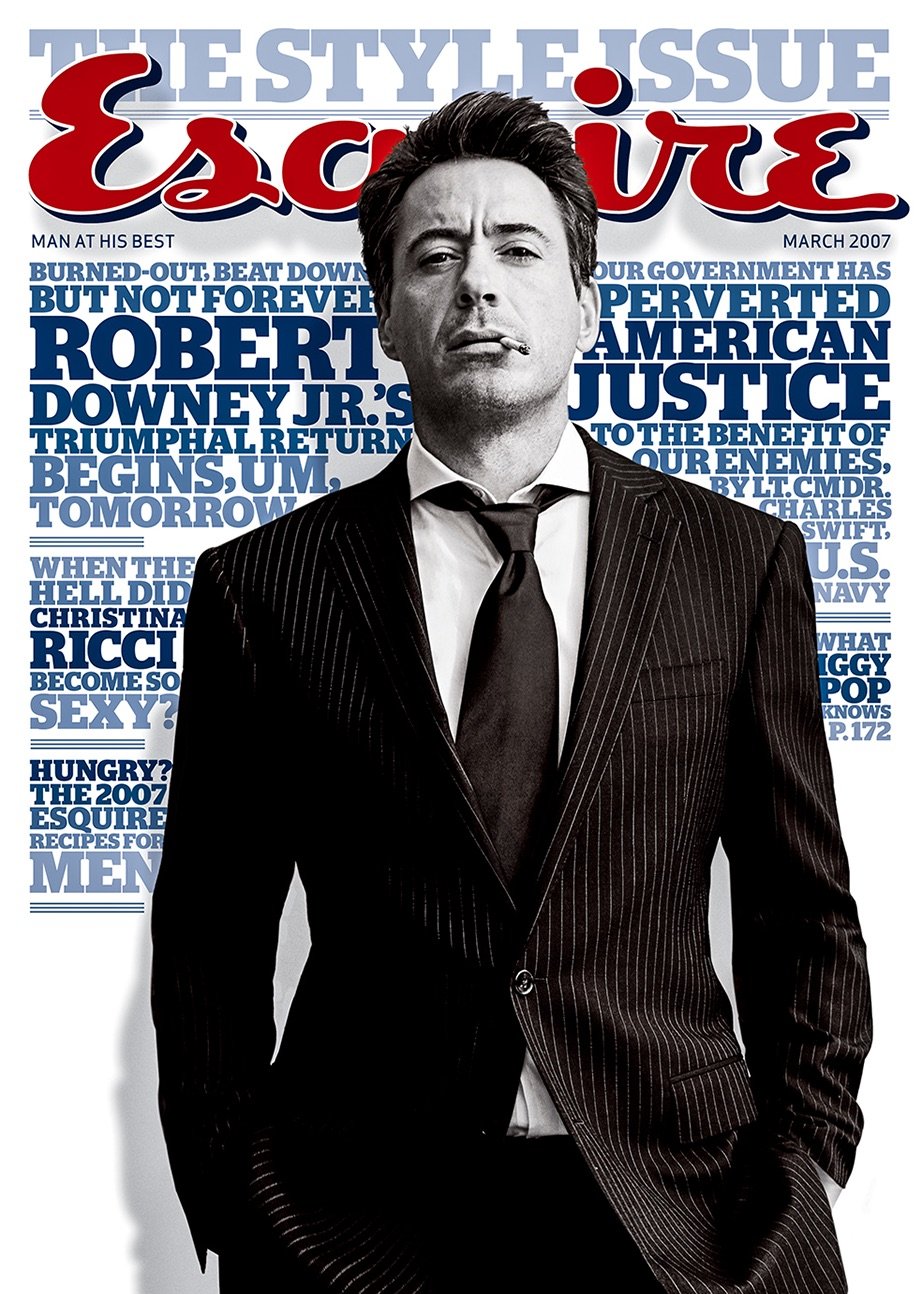

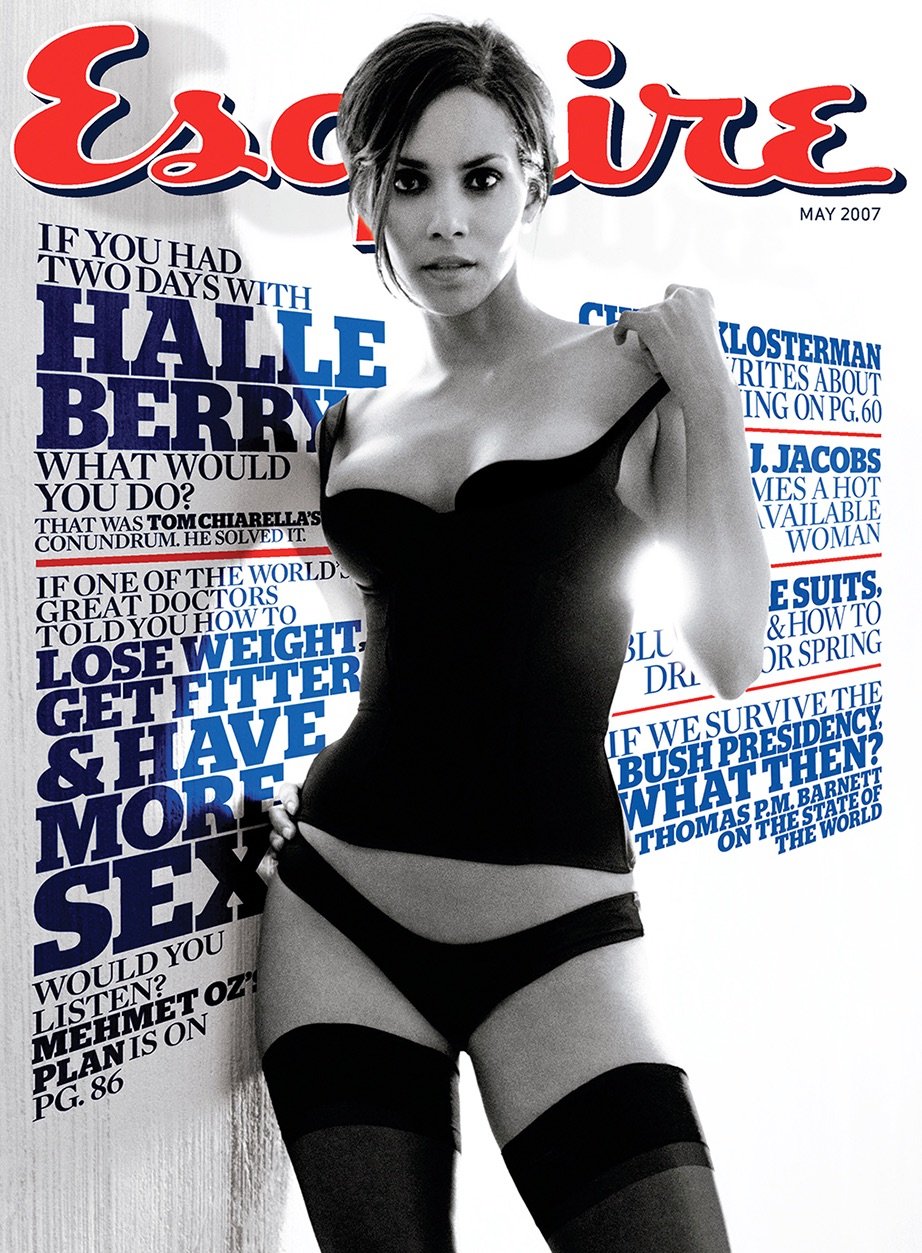

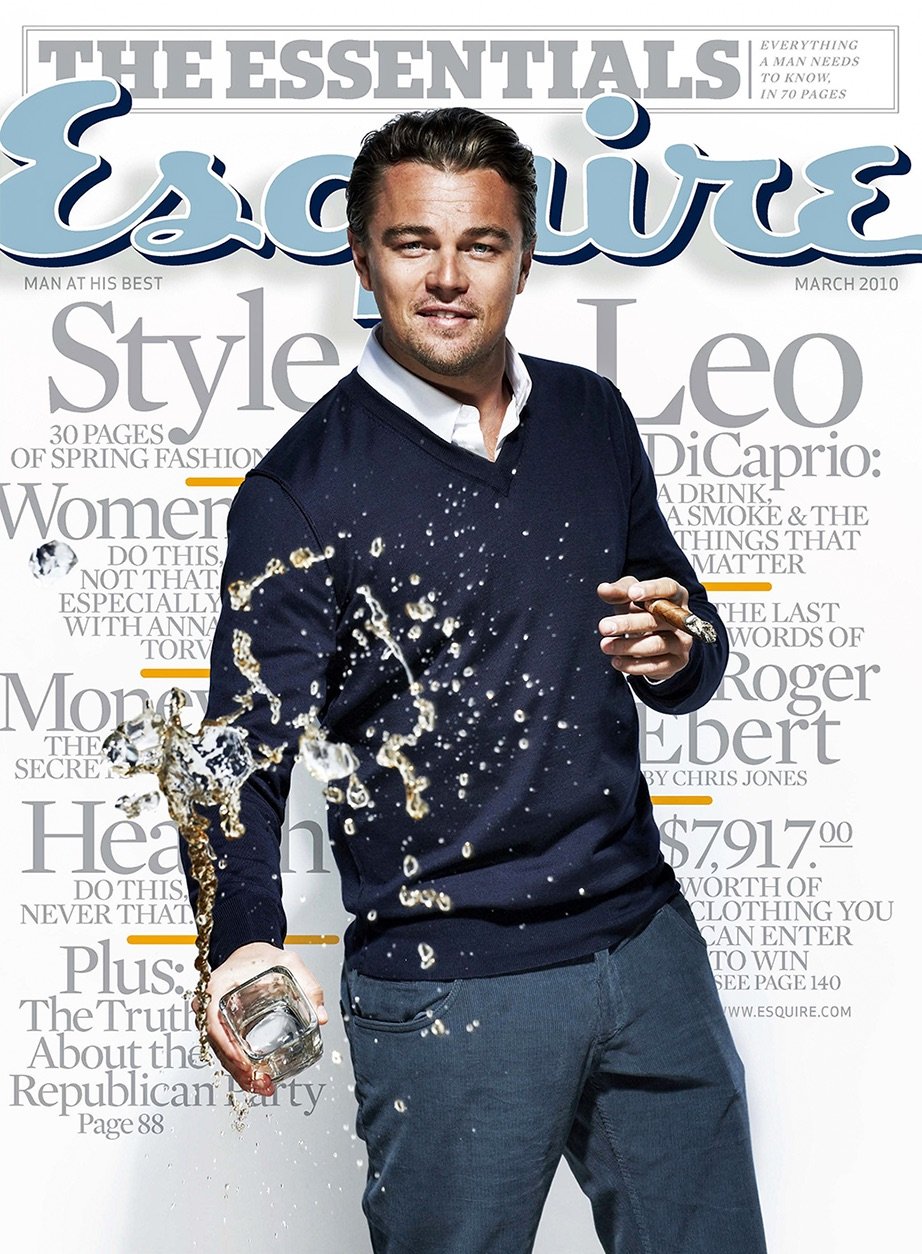

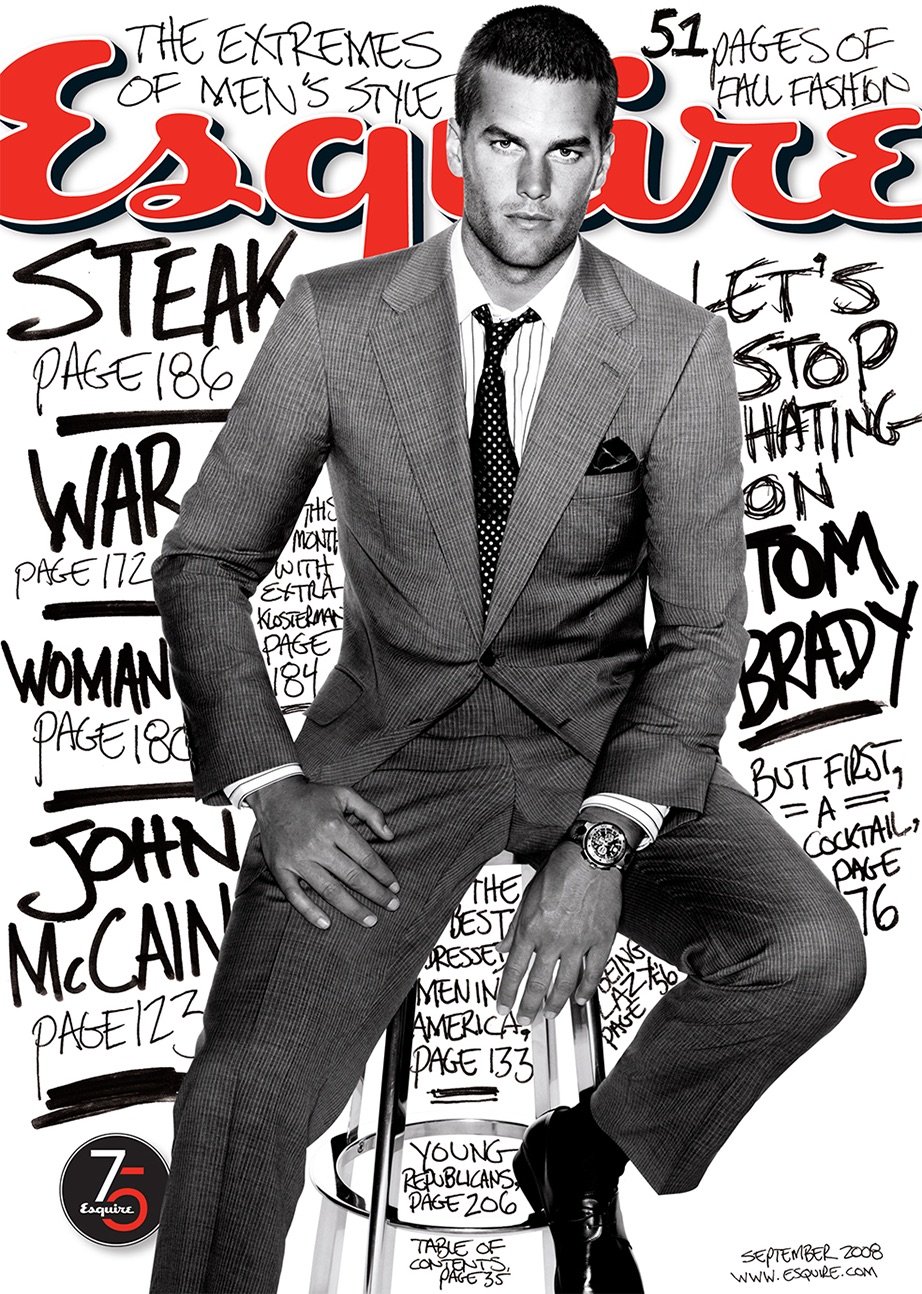

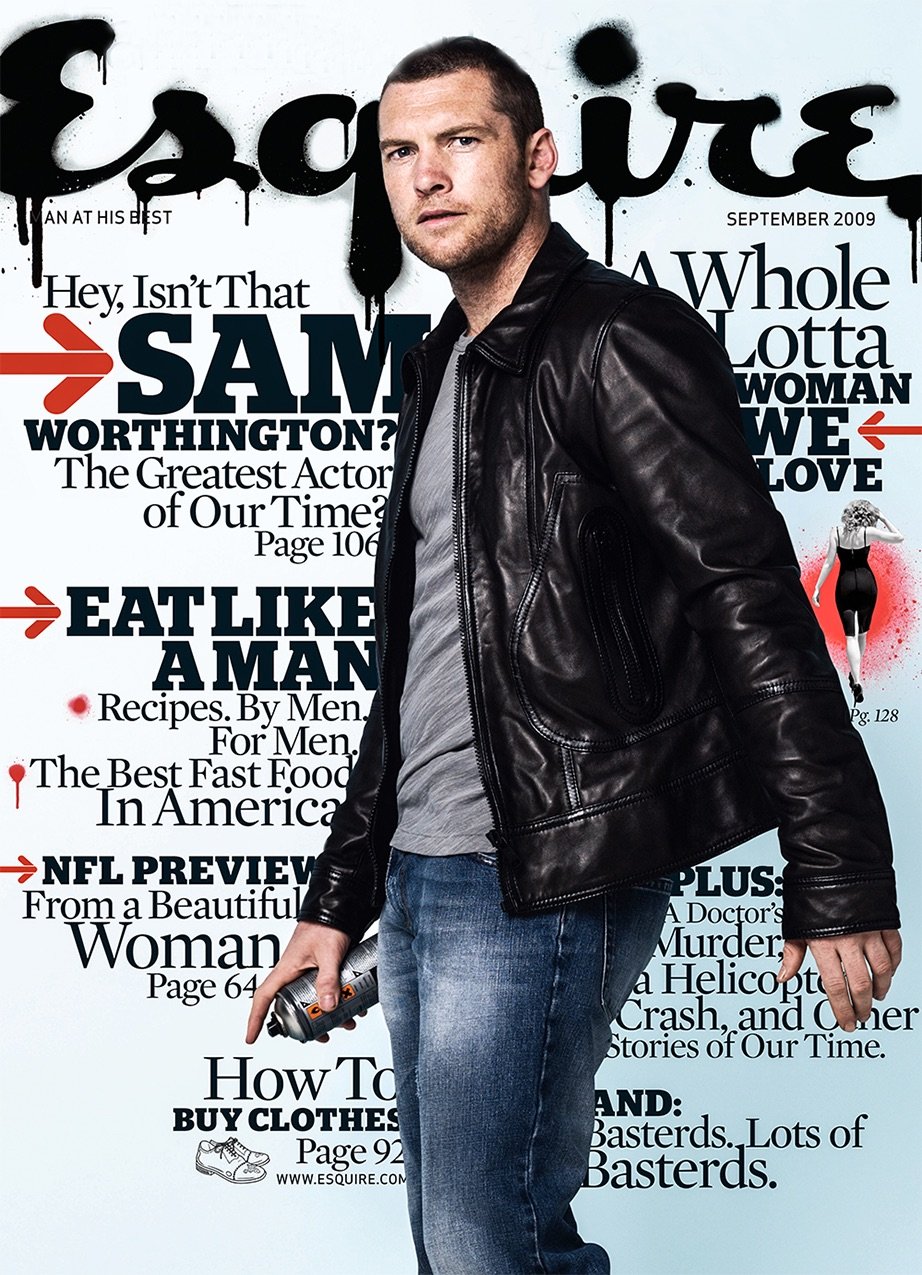

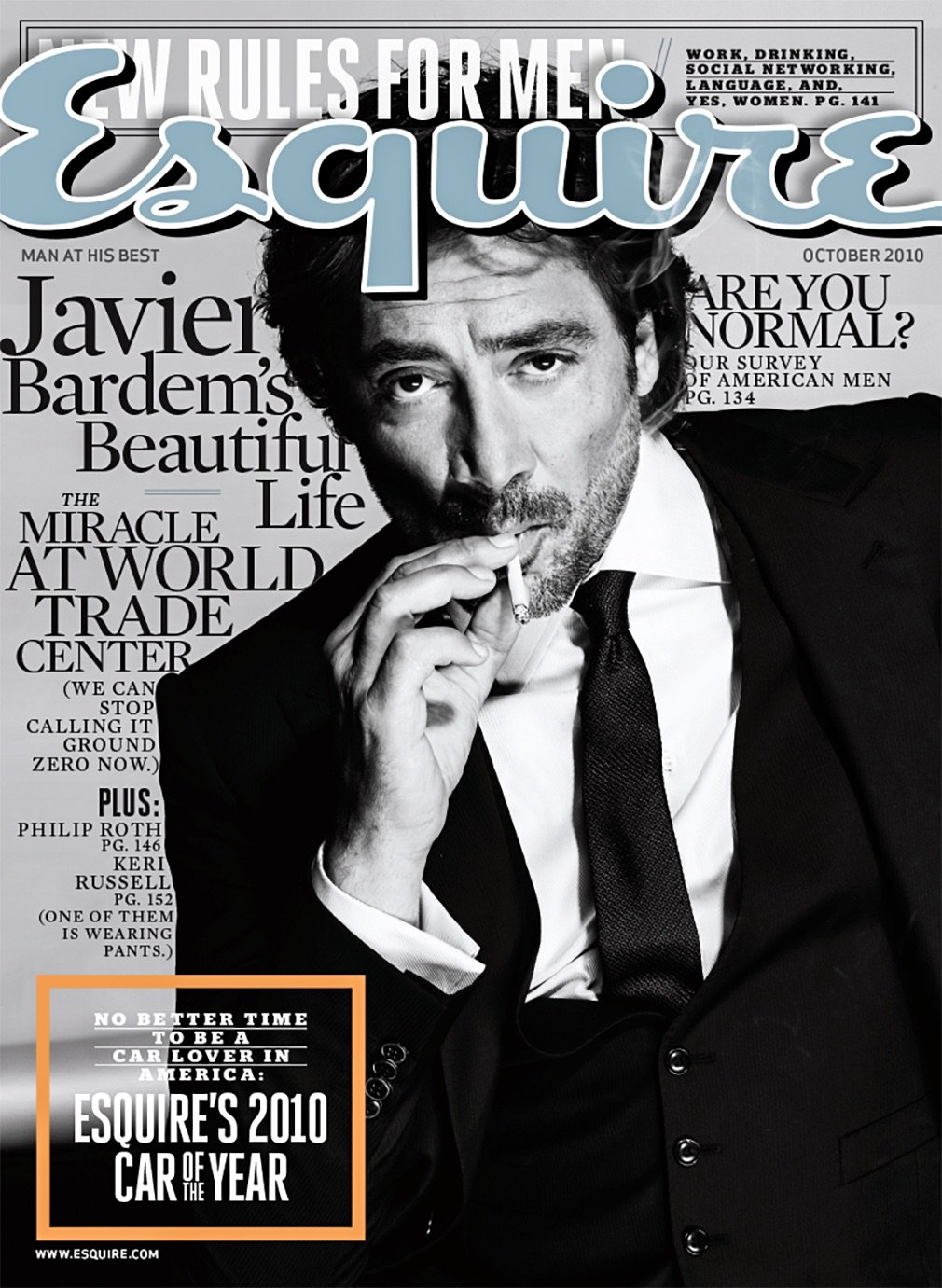

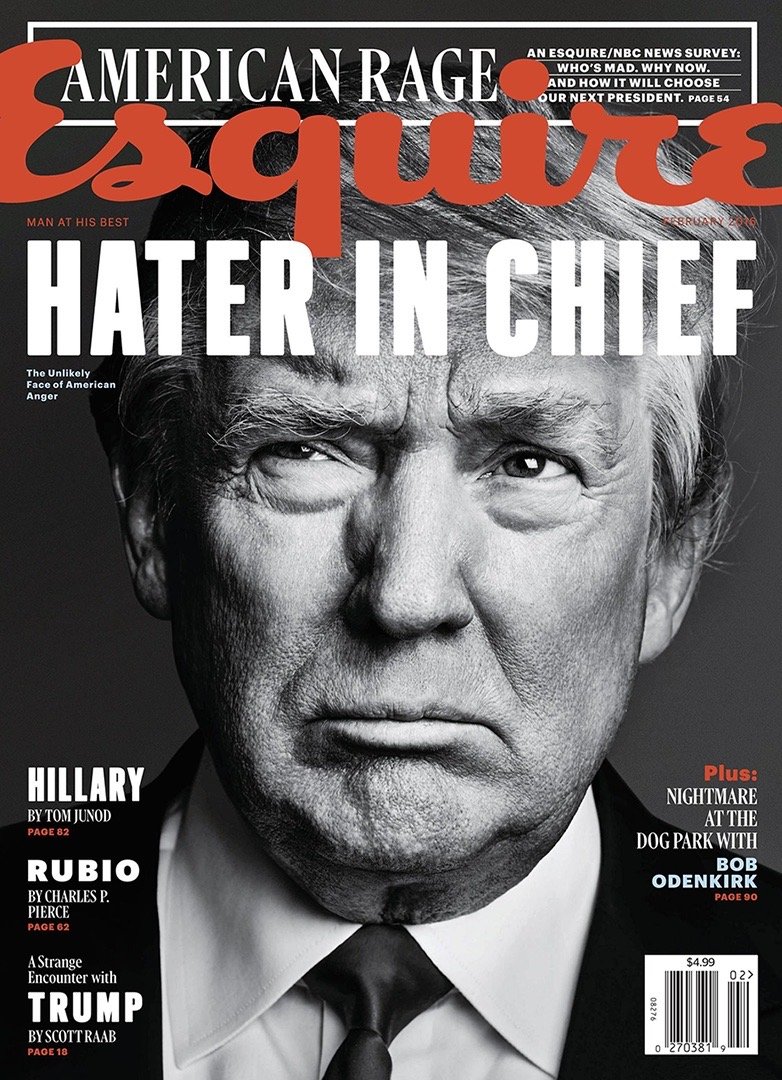

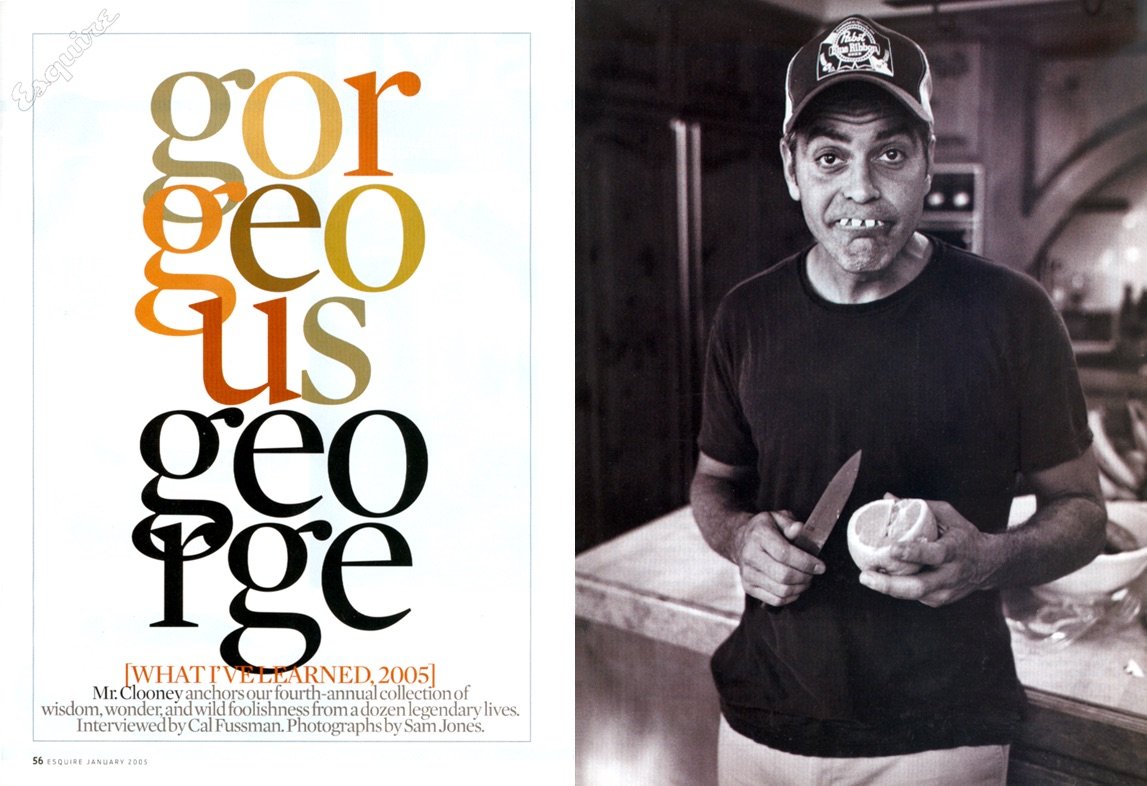

Sean Plottner: Tell us about how you guys came up with those crazy type covers. I think that was starting around 2006. The wall of type.

David Granger: Yeah, that was right around that time. It was like 2006. So we had this guy, Daniel Craig, who was going to be on our September cover. And it was a big chance—that was before he’d become Bond. The reason we’re putting him on the cover was because he was going to be in his first Bond movie. And the word out of England was: “This guy sucks.”

So we do a photo shoot with him and the photos are miserable. The guy has one facial expression: these pursed lips. And I’m thinking, “This is a failure!” But on the other hand, I looked back at the cover before it, and it was just one of those “magazine” covers. John McCain was on the cover, and it had a number on it, and it had some traditional magazine cover lines.

And I was so sick of that. And I knew Daniel Craig was going to fail because he was going to be the worst Bond ever, and he had this pursed-lip look on his face, right? And so I went into Curcurito’s office and I was like, “You’re going to have to save this.”

And he goes, “What do I do?”

And I go, “Look, I want you to create something that looks like the Vietnam War Memorial behind Daniel Craig. I’ll give you all the words. You just create this wall type and I want it to look like the Vietnam War memorial.”

And he goes, “Okay, okay. Give me the lines.”

And I wrote all these sentences. They weren’t sentence fragments, like most cover lines are. They were full, complete sentences like, It’s been five years since 9/11 and nothing’s happened. And we’re still pissed off. Lines like that. You know, like full sentences. And I gave all these lines to Curc. And it’s a lot of words. And about an hour later comes into my office and he goes, “I don’t understand.”

And I go, “Come on man, like the Vietnam War Memorial.” And I stand up in front of the wall. And I’m like, “Just words all over.”

He goes, “I’ve never seen the Vietnam War Memorial.”

And so we started calling up pictures of Maya Lin’s masterpiece. And he was like, “Oh.”

And so he started doing that. And then he varied the sizes of the types and the emphasis. And we created this wall of type behind Daniel Craig, and it did amazingly well.

And for the rest of the time we were there, with certain exceptions, we just loaded it up. The type became the point of the cover. It was like, This is a magazine of ideas and words. Let’s show that on the cover! We have this famous person, but let’s show what we’re about in the words that are adorning and overwhelming the cover.

And then we did stuff like, we blew out the Esquire logo so that it couldn’t be contained by the cover, because Esquire’s a bigger idea than can be contained in any magazine cover—or magazine! It was like, you just start messing with it.

You were asking about—or maybe I was just blathering on about—little stuff and attention to details and stuff like that. I hated when a page only did one thing. I mean in feature stories it’s okay, but like a front of the book page? I hated when it only did one thing. It’s like an essay or something. A column. And I always wanted there to be like three or four things that were interesting on that page.

And so there was this guy, a young editor, and when I’d get particularly frustrated with a page, because it was interesting enough, I’d take it over to Nate [Hopper]. And I’d go, “Nate, would you just fuck this page up for me?” And he would. And they got really interesting.

Sean Plottner: Those covers were so memorable. I personally love them and thought they really stood out. And it’s interesting to go on the Esquire archive and look at how they’ve evolved with the different fonts and the hand drawn…

David Granger: It was like trial and error. It was experimentation. And some of them weren’t very good, but we were trying to be loud. We had this consultant guy, Steve Blacker, and the only thing any circulation consultant never said to me that stuck was Steve going, “Look, don’t just think about the newsstand…” You know, because I was saying, “Well, you know, maybe we should do newsstand covers and then do subscriber covers, so we don’t have as many cover lines.”

And he’d go, “No, no, no, no, no. It’s not just about the newsstand. It’s about the ‘homestand.’ Think about when a magazine comes into your house. It’s competing with everything that’s on TV. It’s competing with games, and every other diversion. You’ve got to draw their attention.”

And I, that made sense to me. And so we made our covers as loud as they could be.

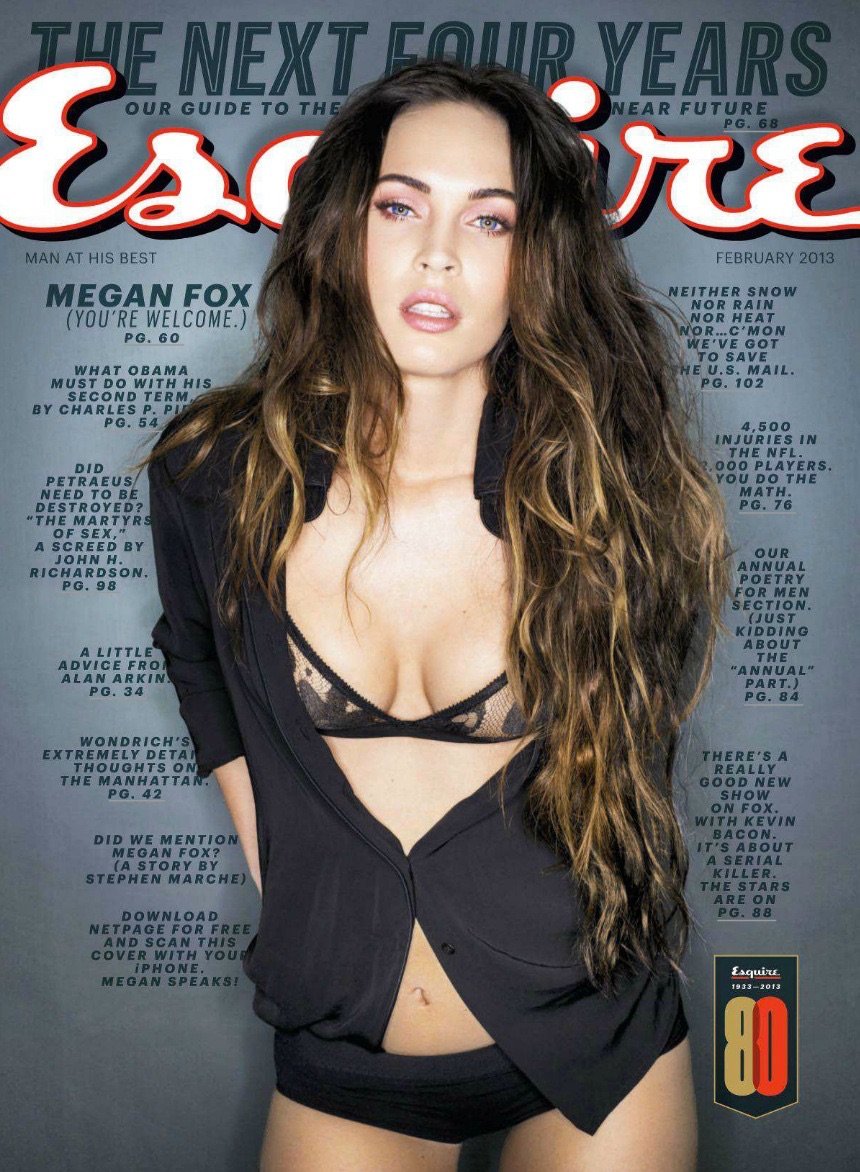

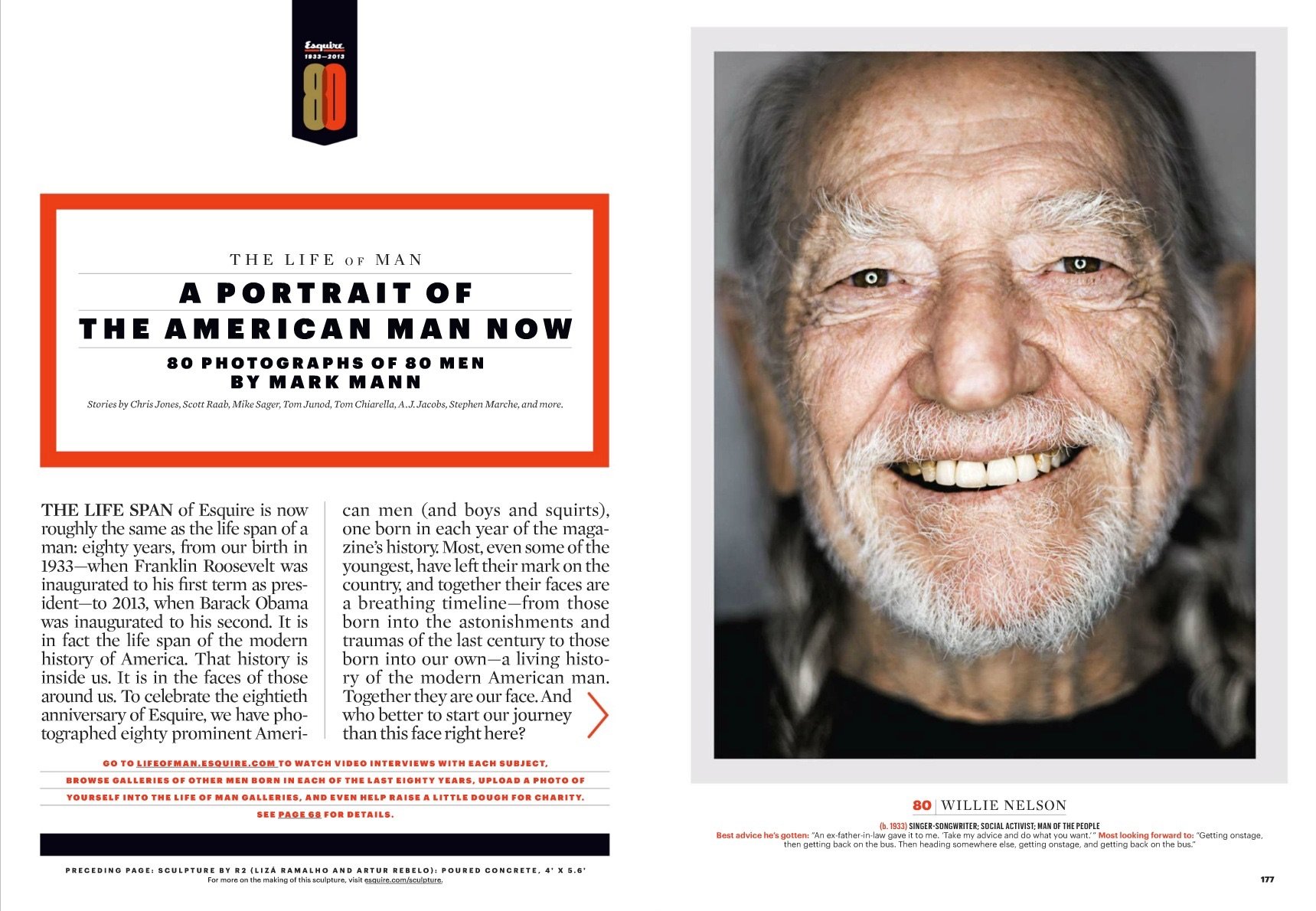

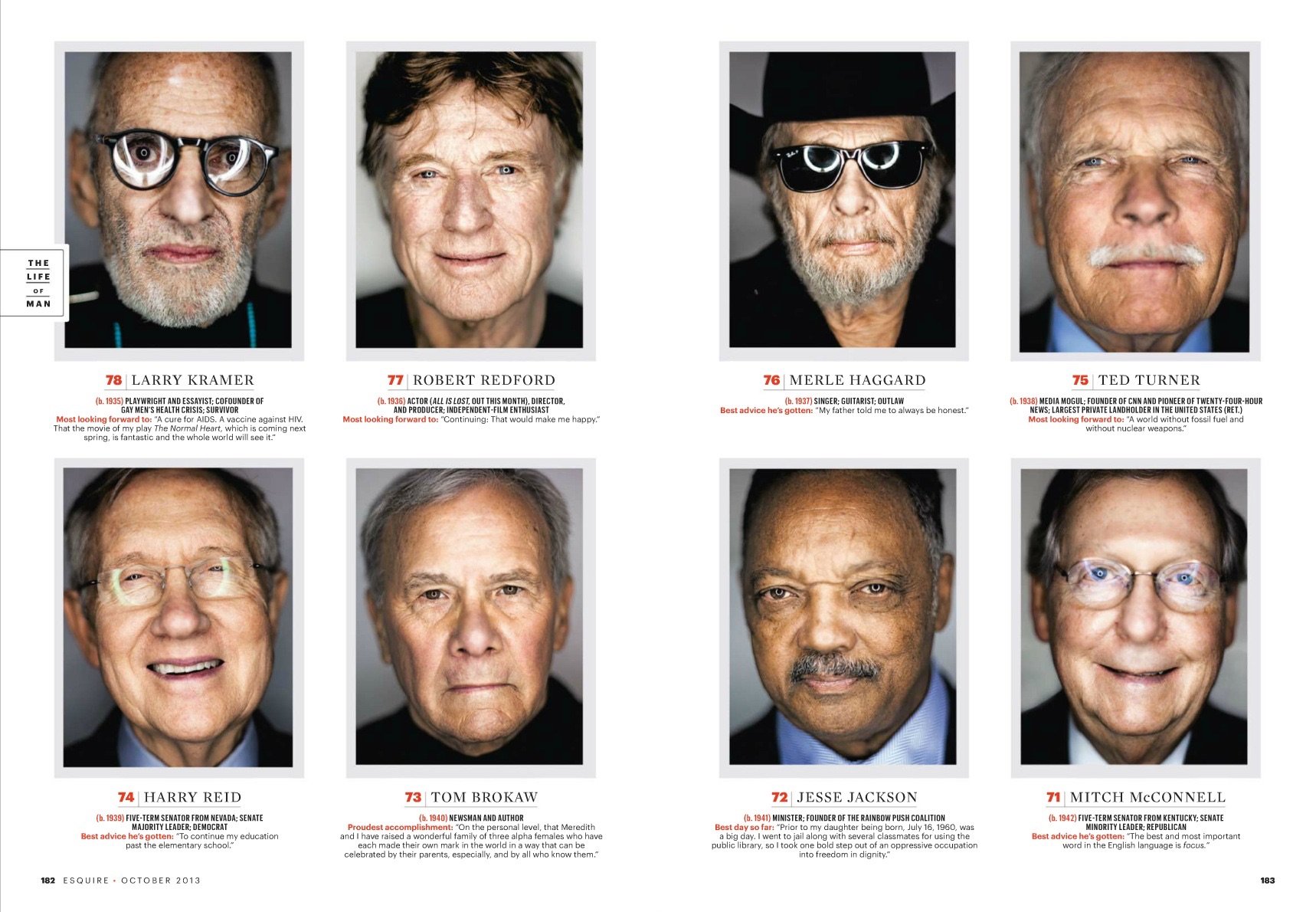

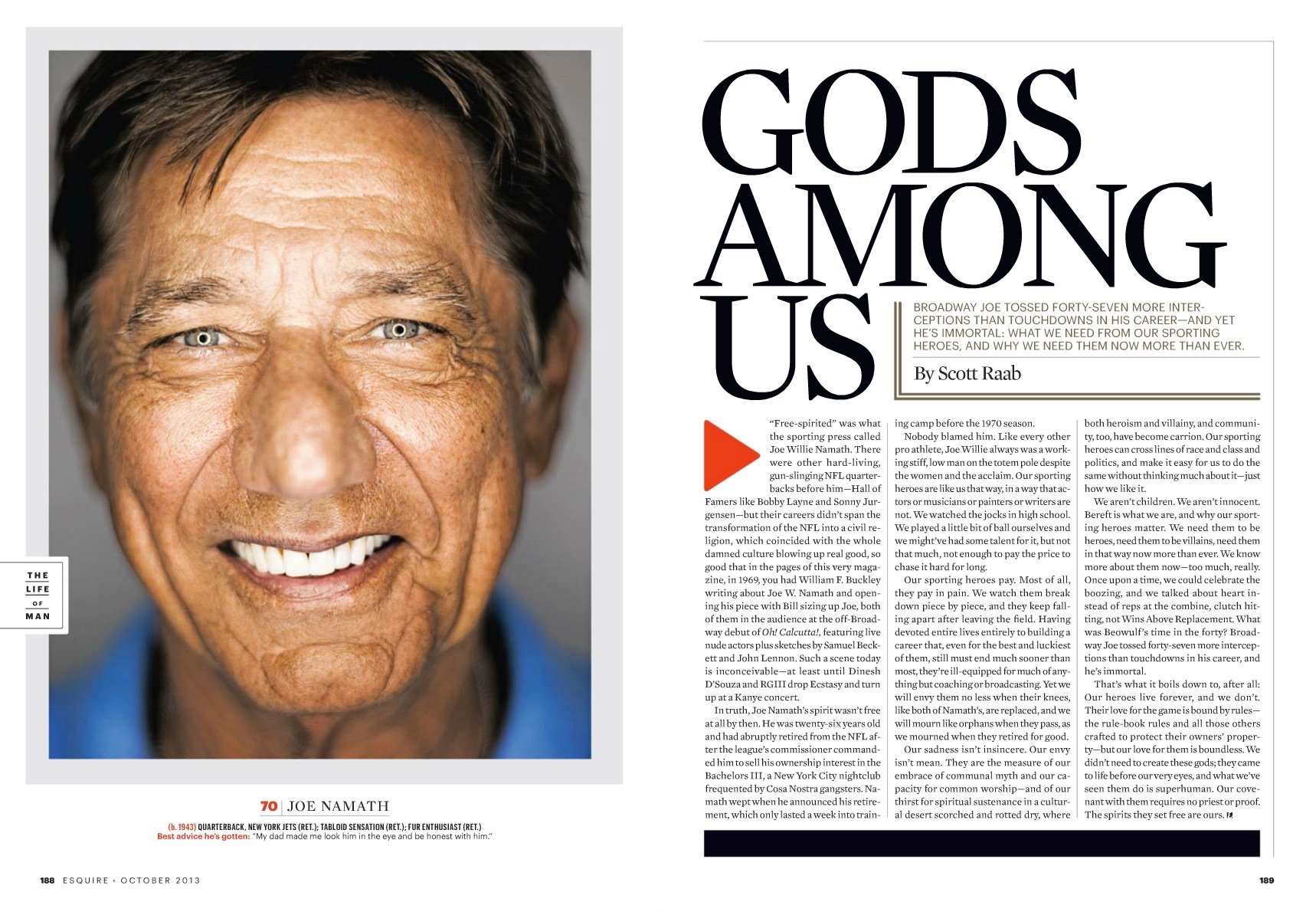

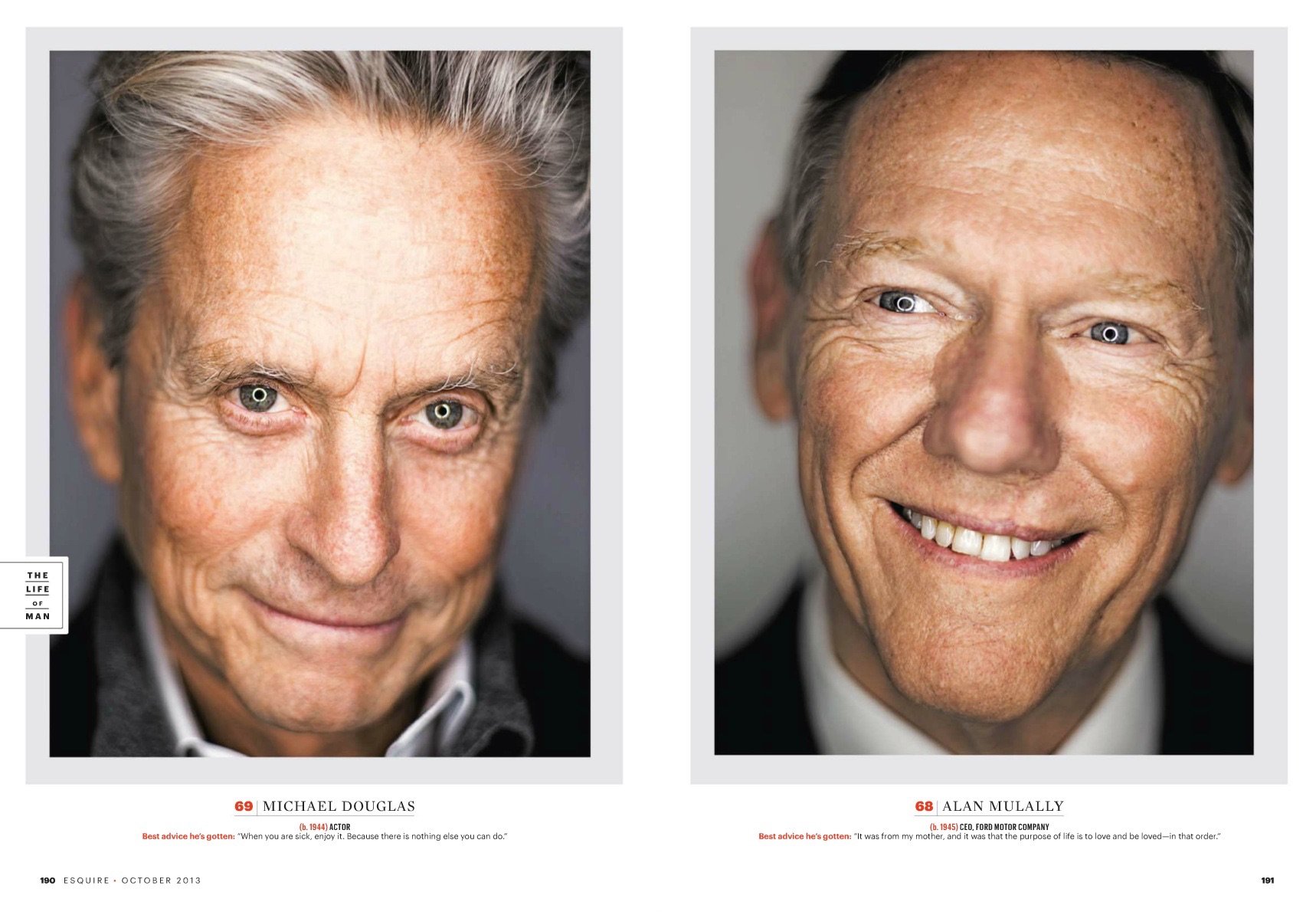

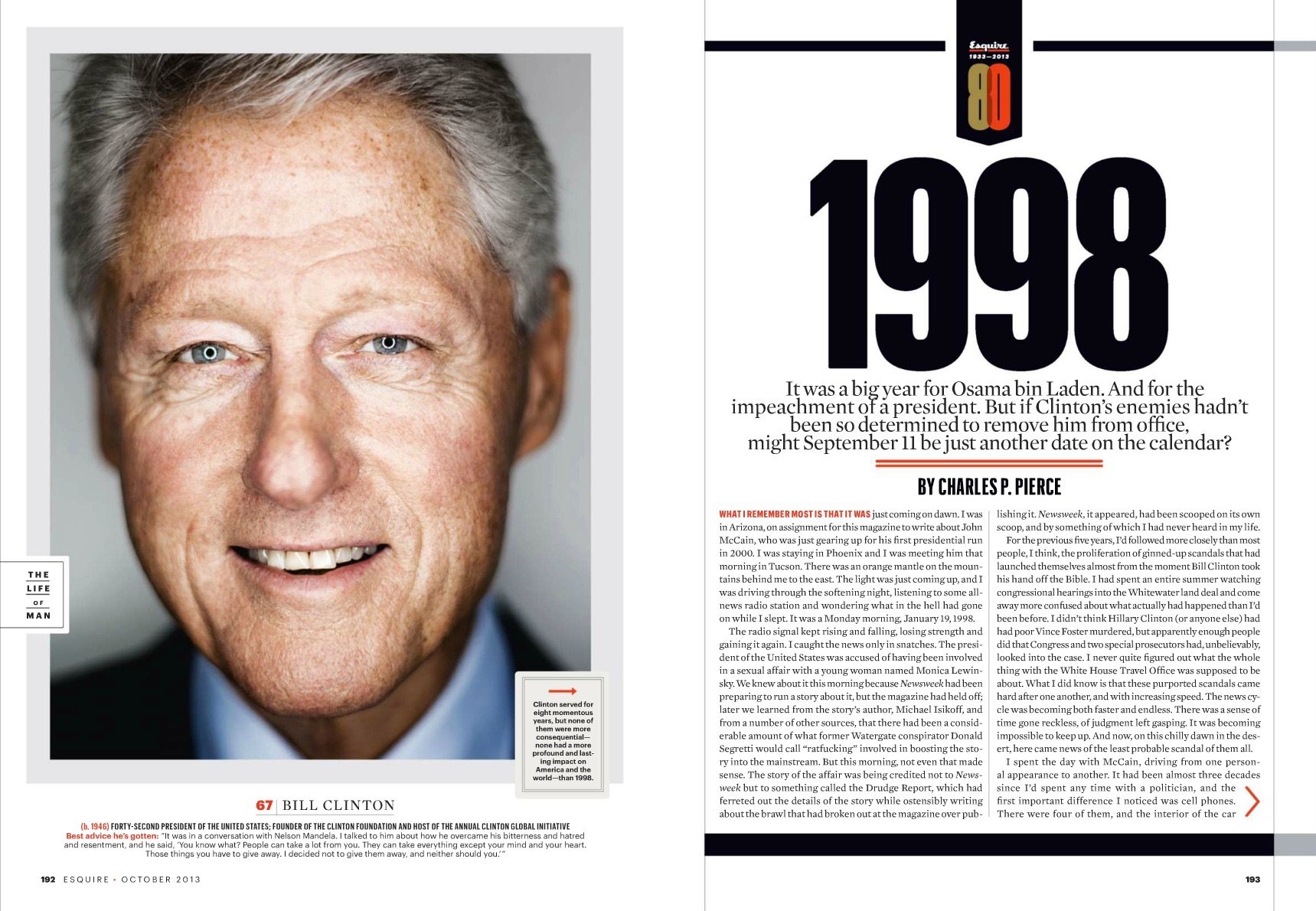

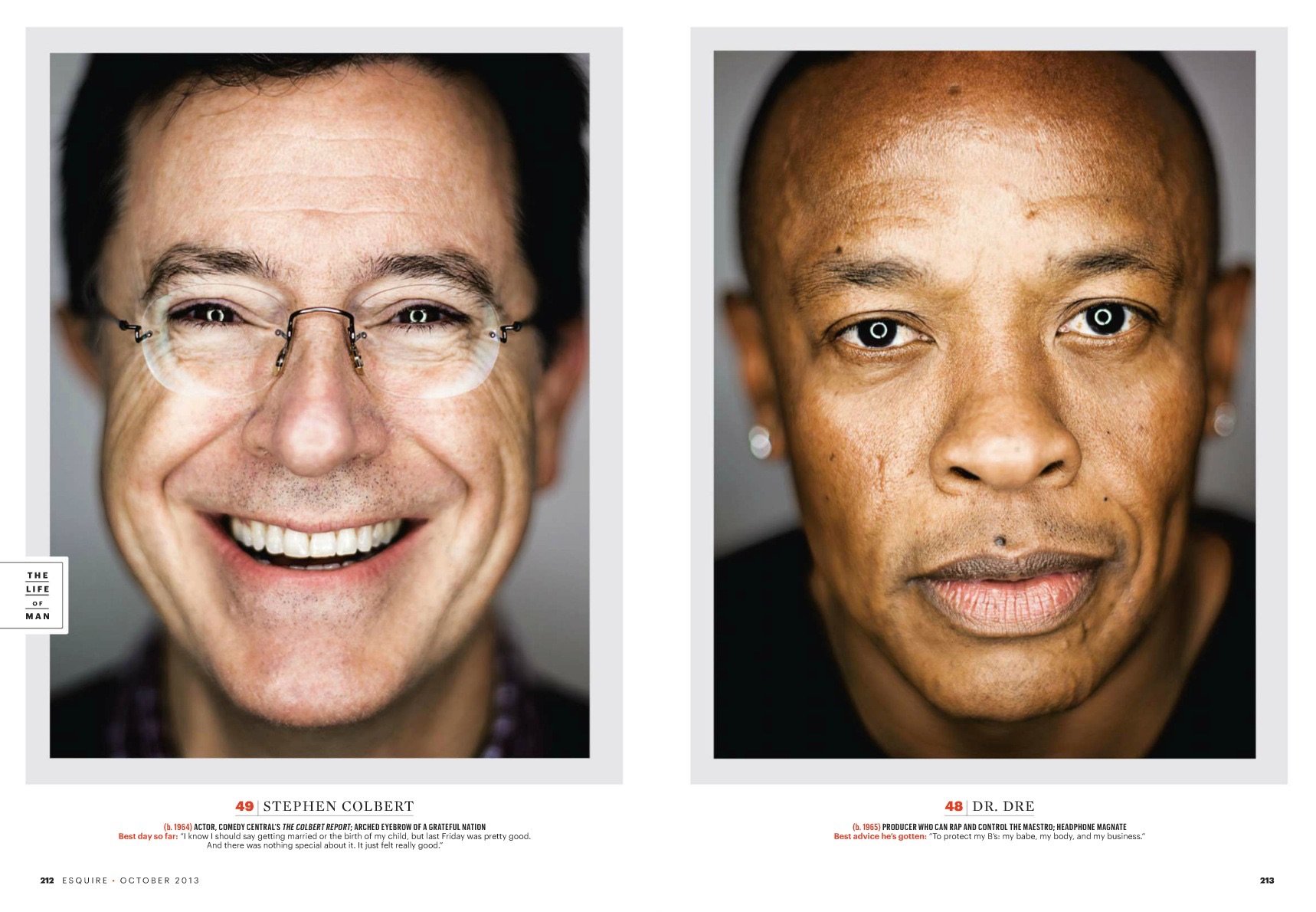

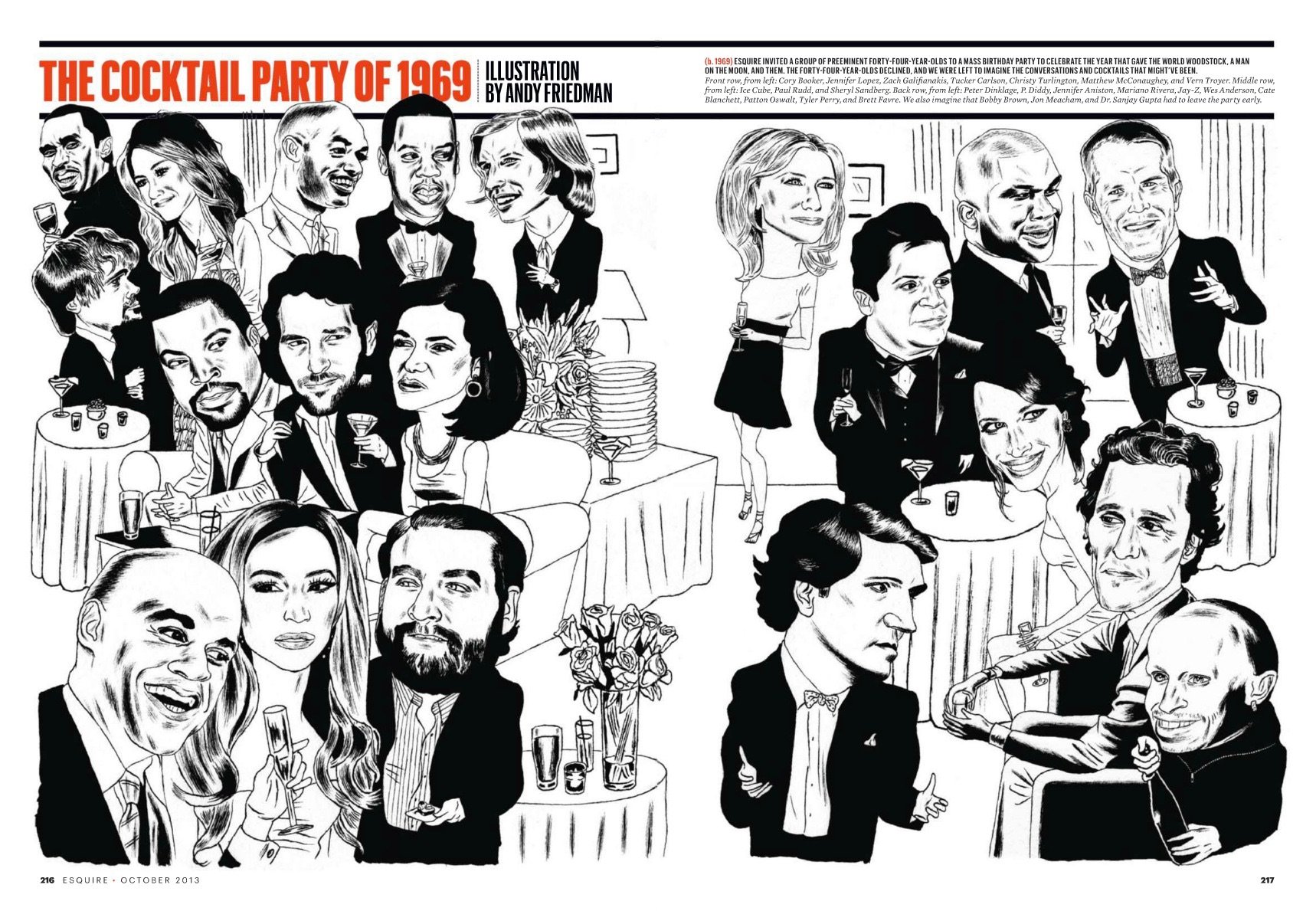

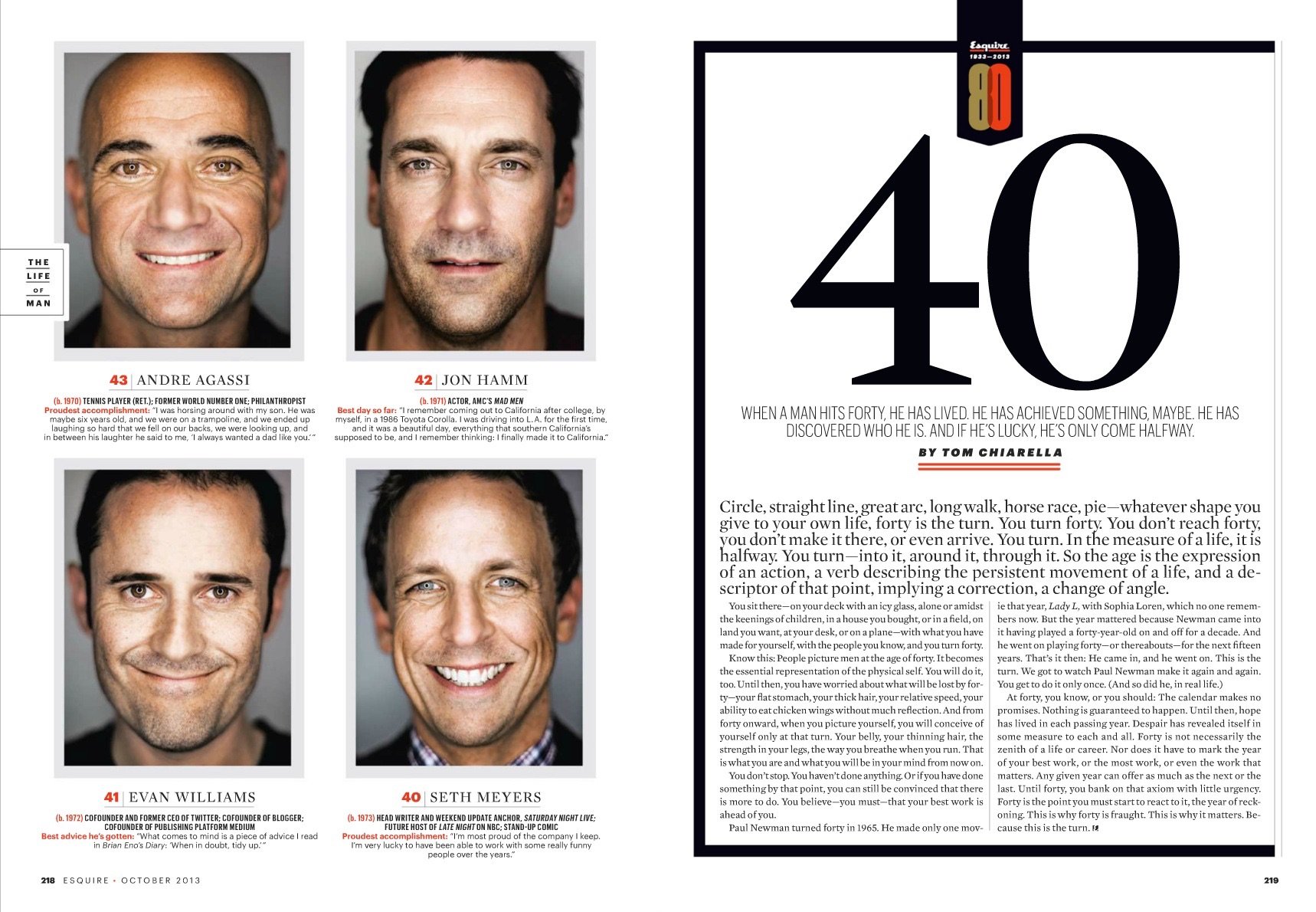

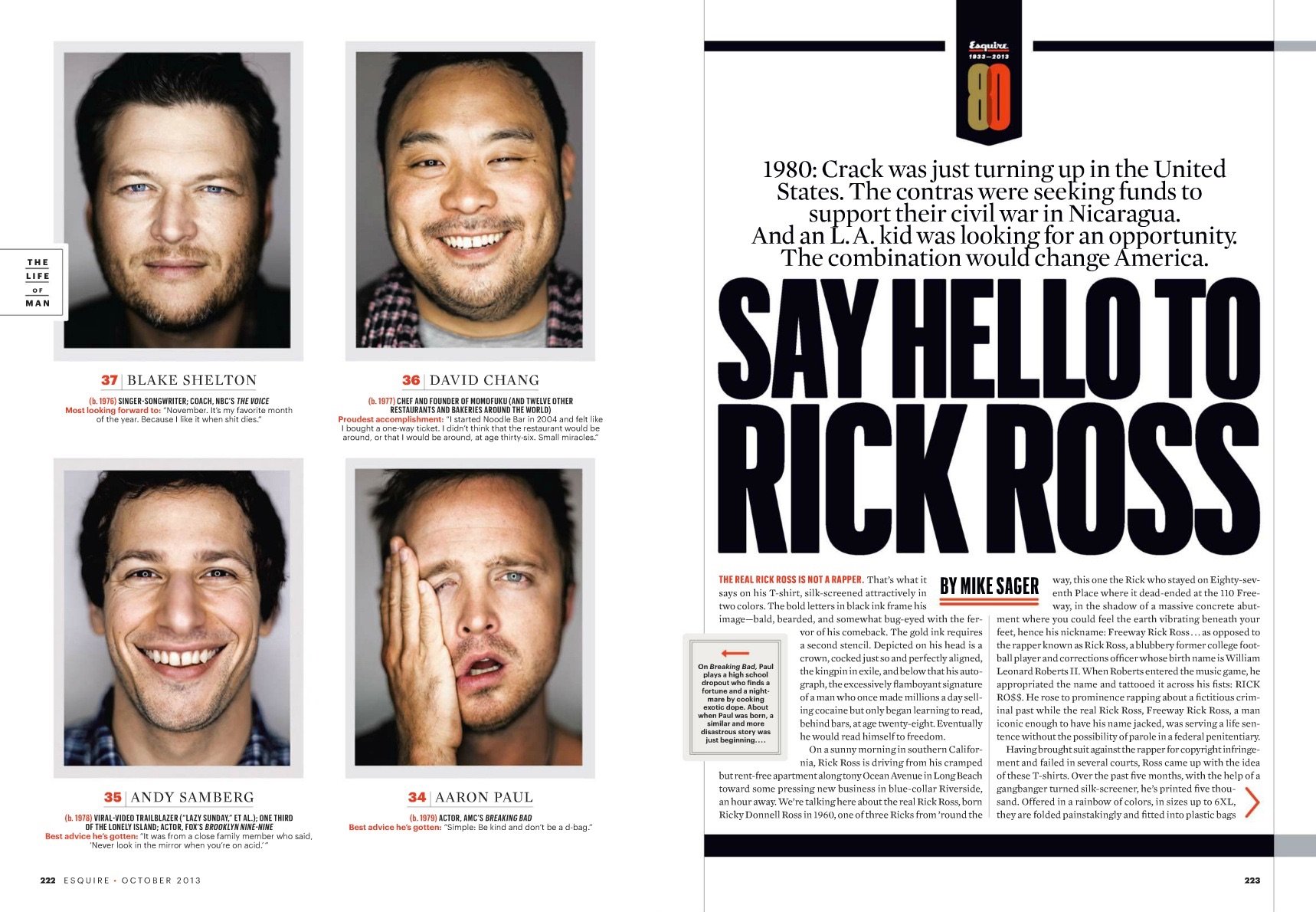

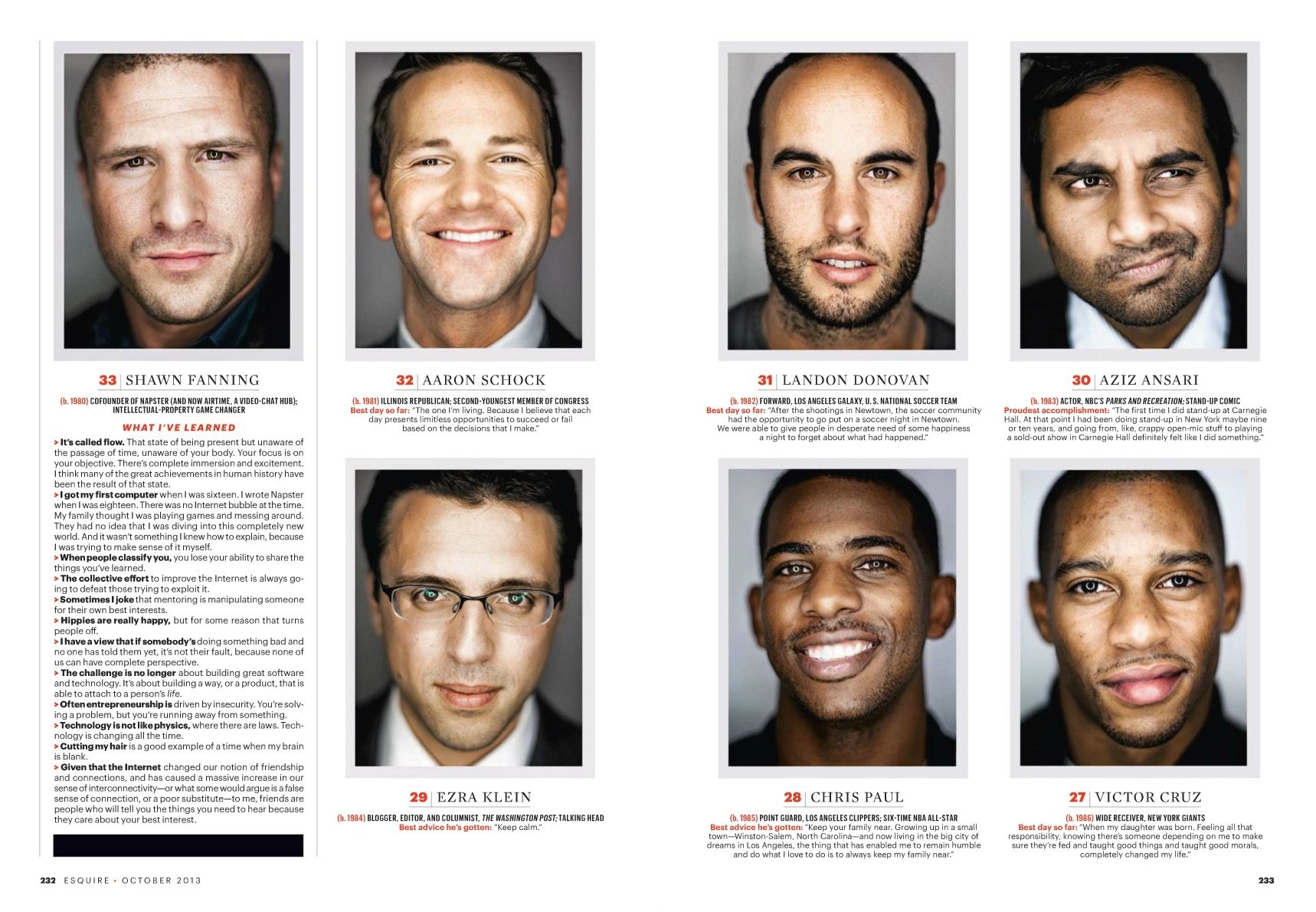

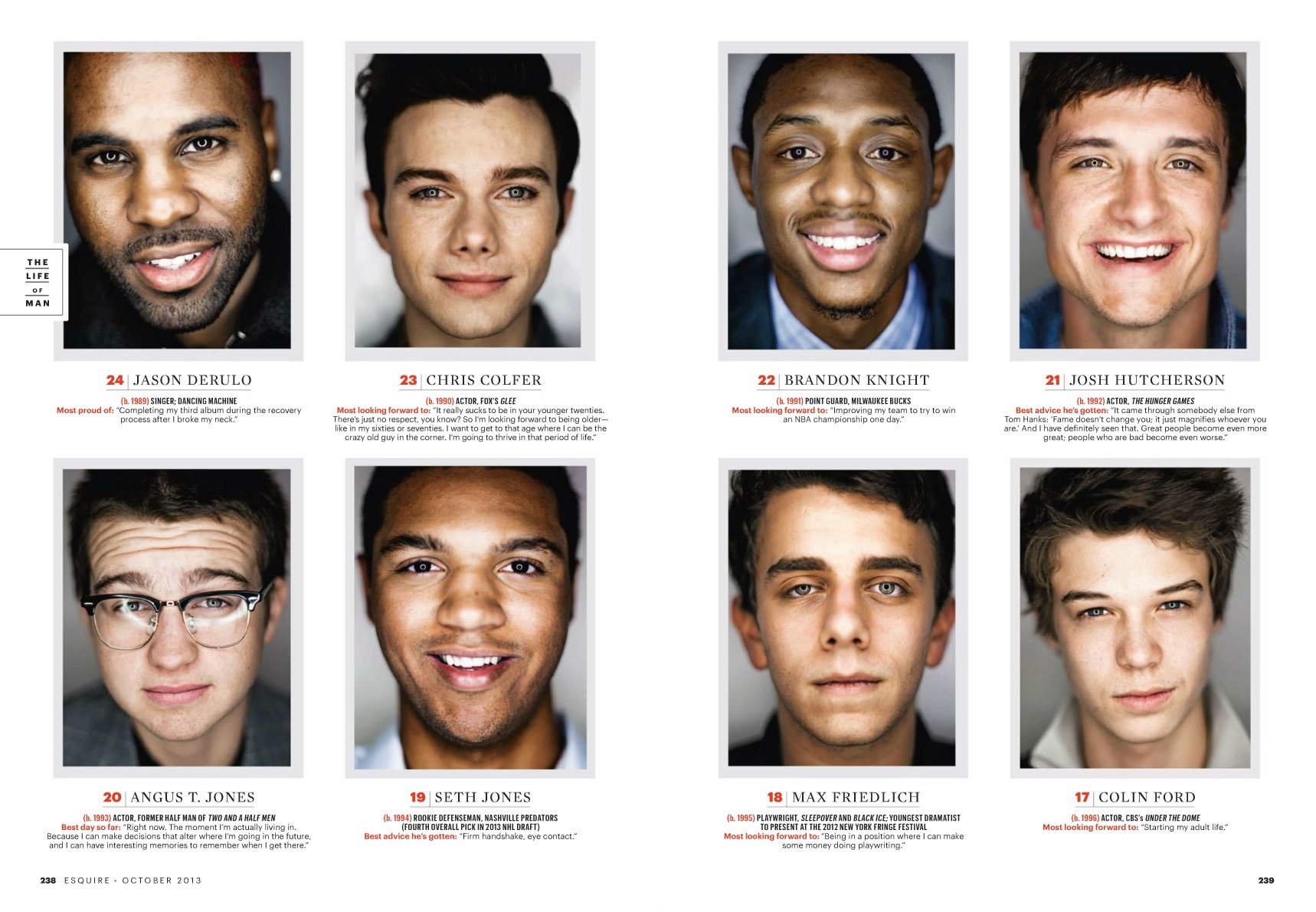

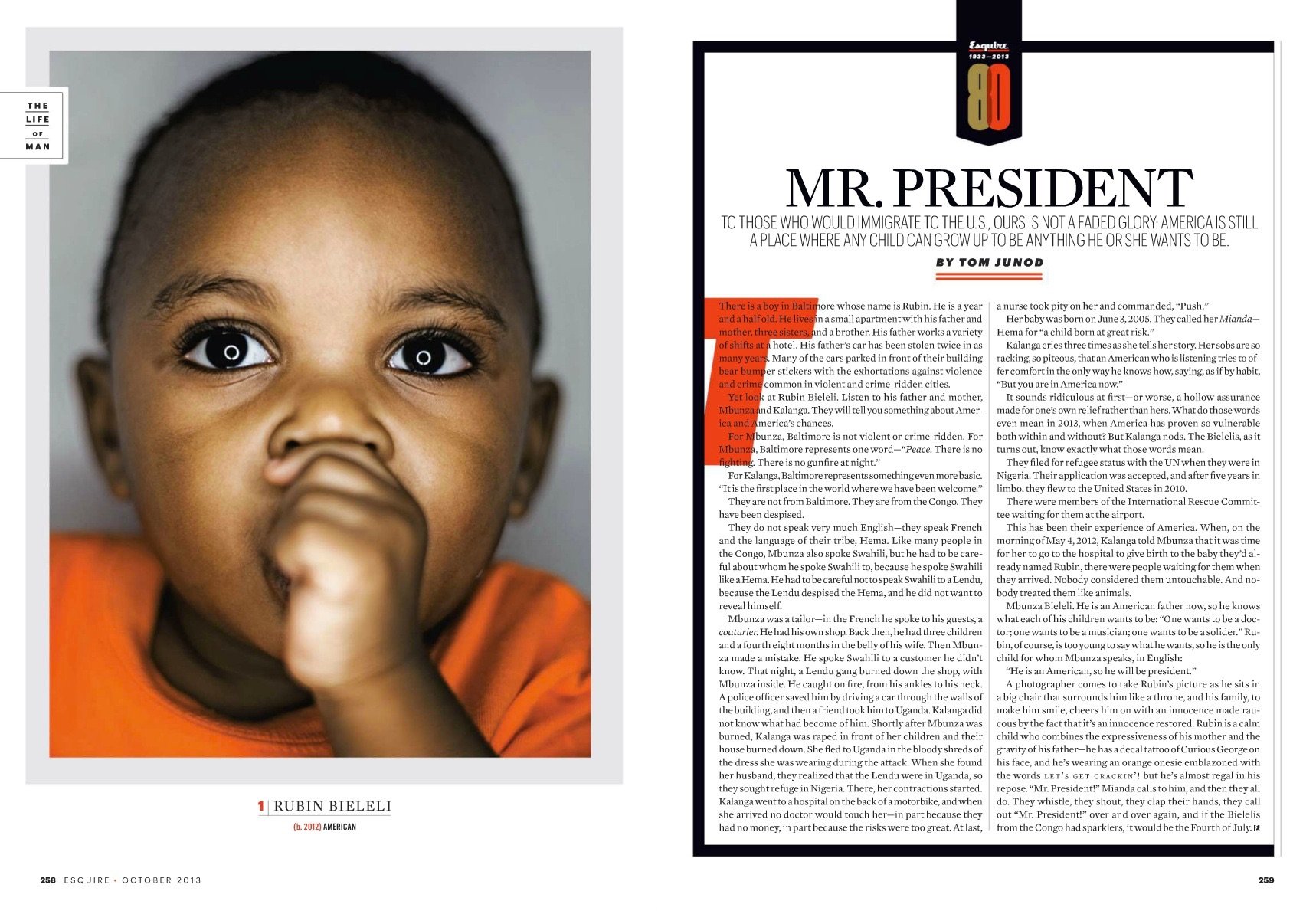

A 2013 special 80th anniversary issue themed “The State of the American Man,” featured a man (or boy) at every age between newborn and 80 (Willie Nelson).

Sean Plottner: Let’s just change the pace a little bit, and I’m going to …

David Granger: … We’re going to play a slow song?

Sean Plottner: Yeah. We’re going to slow dance to a little Bread. Actually, we’re going to pick it up a little bit. I’ll say something and then you just tell us the first thing that comes to mind and you can elaborate.

David Granger: That was fraught baby. That was fraught. It was one of those things that people associated with Esquire. They hadn’t read it since, like, 1968, and we tried to revive it and make it relevant, but this was like when John Stewart was coming on the air and there was political satire every night. And so Esquire had done this annual issue where they did fake headlines and then the stories that went with it, and the real news stories that occasioned those fake headlines.

And it was funny in its day. And we tried so hard to make it relevant and failed every time, including, like, Dave Eggers edited it in the one year that he worked at Esquire. We hired Jay Lovinger, who’s a legend from Time Inc.—but mostly from John A. Walsh—to come in one year. And we tried everything. It just didn’t work. So we killed it. And we killed it right after 9/11. It just just didn’t seem like it was in sync with the times anymore. And I got a bunch of nasty letters from people who, as I said, hadn’t read it since 1968.

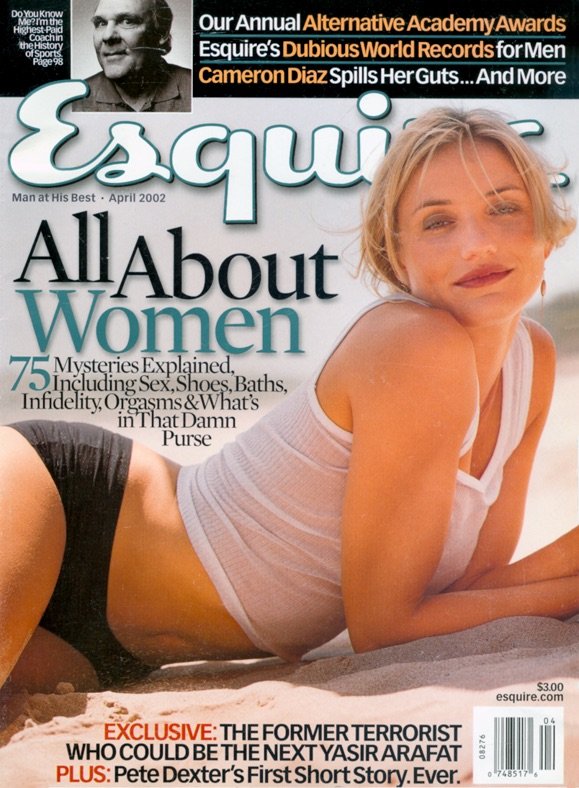

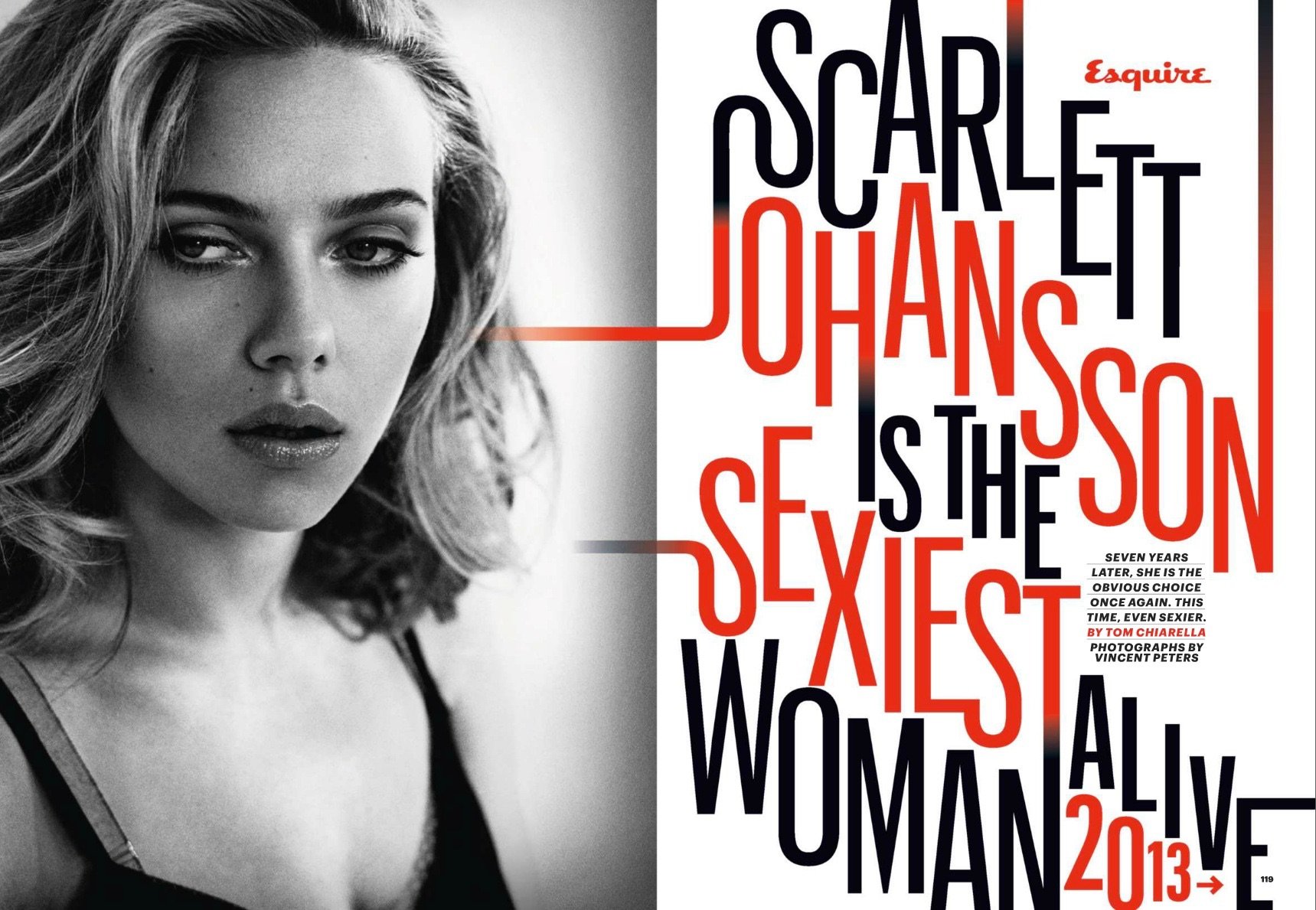

Sean Plottner: Eggers had done it once. I’m going to have to look that one up. “Sexiest Woman Alive.”

David Granger: Scarlett Johansson.

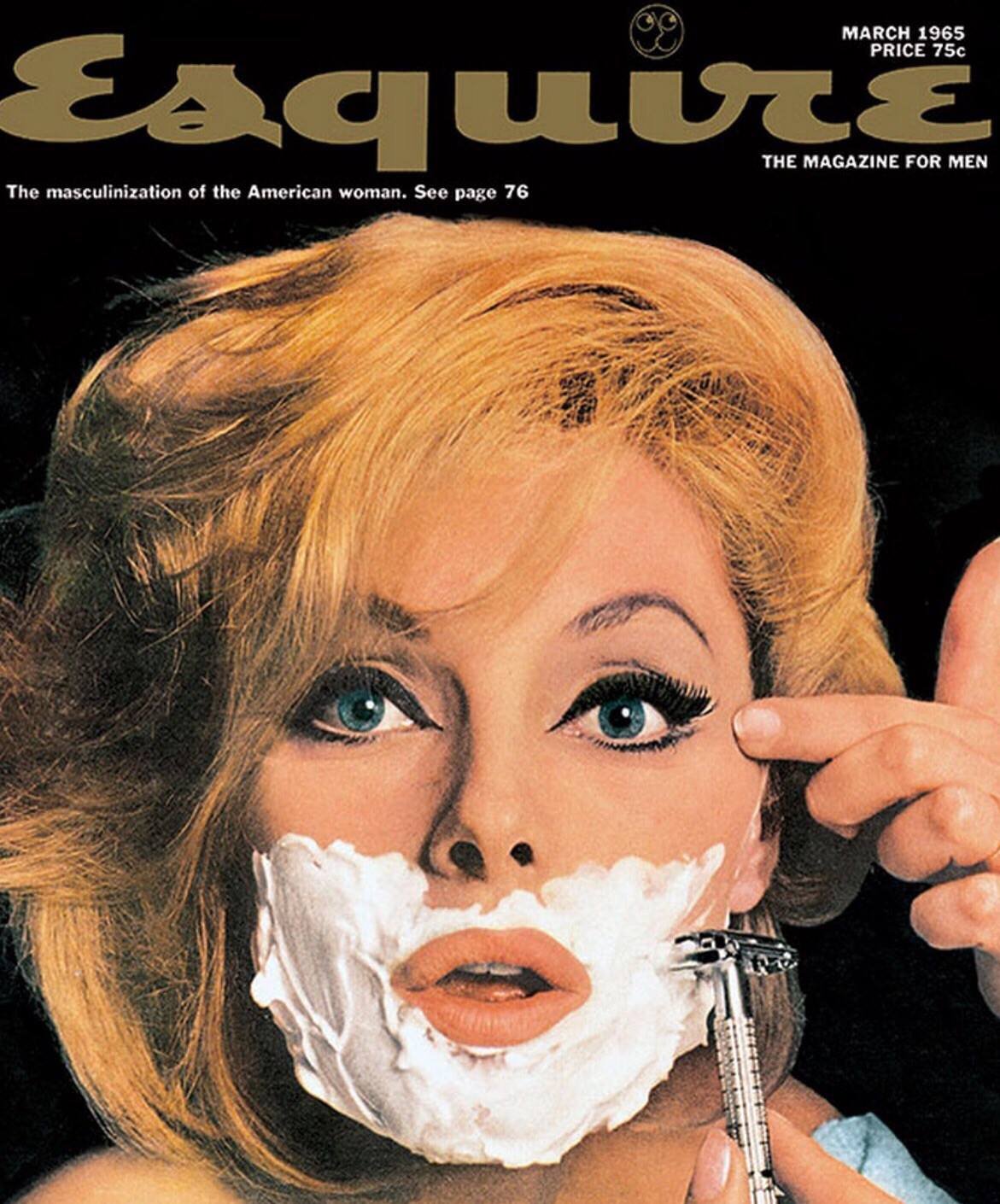

When we put women on the cover, we always wanted to give the impression that the women enjoyed the experience, and give our readers that, rather than doing the thing that men’s magazines—that it’s hard not to do, which is objectify. And so one year we did, over six months, we gave visual clues to who the Sexiest Woman Alive that year was.

You couldn’t see who it was, but it was like in one, she was in her trailer home and on the floor in front of the open refrigerator, and the place was just a mess. All of them were shot in this trailer home in Appalachia somewhere. And in one, she was, like, shaving her legs in the sink. And it just looked like the most down-on-her-luck human being in the world. And it was Scarlett, who played all these roles for us and spent, like, three days shooting this thing just to do this long, slow reveal of who the Sexiest Woman Alive was. It was tons of fun.

Sean Plottner: “Lad mags.”

David Granger: Yeah. When I got to Esquire, that was when the “Lad Mag” thing was happening. I can’t even remember the names of them anymore. Ugh. God.

Sean Plottner: FHM. Maxim.

David Granger: Maxim. Maxim. Maxim. Maxim. Maxim. And that was one of the things that, when I talked about second-guessing earlier—all the circulation people, all the ad sales people—that was the thing that they most second-guessed me about. It was like, “Maxim’s successful. FHM’s successful. Why aren’t you guys more like Maxim?” You know?

Sean Plottner: Yeah. They’re putting Mr. Rogers on the cover. Sure.

David Granger: Yeah. I was at a cocktail party, speaking of Mr. Rogers, with Jann Wenner once, and I was complaining to him about newsstand sales and he was commiserating with me until he looked at me and he said, “Wait a second. You’re the guy who put Mr. Rogers on the cover, aren’t you?” He stopped commiserating with me right then.

Sean Plottner: Were the Lad mags competition for Esquire?

David Granger: Yes. They were competition for readers and competition for advertisers. And I think one of the reasons that Maxim succeeded was because men’s magazines had stopped giving men advice. And even though the advice in Maxim was mostly bad advice, it was advice.

And so I think men’s magazines had abdicated their role of offering guidance and that was one of the things that I worked really hard with my staff to try to do. We had this “Martha Stewart Moment” once when I was driving to tennis with a friend of mine and it was in my first couple years at Esquire and he goes, “How come there’s not a Martha Stewart for men?”

And that day I went to the library and I found the last three years of Martha, and I read it. The next morning I had an emergency meeting, I had the staff come in and I was like, “You guys need to read Martha Stewart.”

And they’re like, “What?”

And I was like, “No, no, you’ve got to read it. This magazine’s amazing because this is what Martha’s message is to her readers: I love you. I love your life. And if you follow my advice, your life is going to be better.”

And I was like, “We’ve got to do some of that!”

It was one of those moments where I was like, “Okay, it’s getting a little clearer what I’m supposed to be doing here.”

Sean Plottner: Frank DeFord. The editor at The National.

David Granger: Okay, two things. First, one of the three greatest sports writers of all time. And one of the great writers of all time. Second, way too nice a guy to be the editor-in-chief of a daily national newspaper. Frank was such a nice man.

You know, you got the nice letters from him, in purple ink, and all that kind stuff. He was just a great man. But that led him to say ‘yes’ to everybody. Even when there were pitch battles at The National—especially the ones I saw between the news side and the magazine side—Frank just said ‘yes’ to everybody. So, I love the guy. Just too nice a guy to be an effective editor-in-chief.

“The big stuff is hard in its own way, but it’s the little things that people are going to remember—or they’re going to enjoy—and it establishes not just a voice, but a whole environment of entertainment.”

Sean Plottner: Art Cooper, editor at GQ.

David Granger: Okay, here’s how lunch was with Art: Every once in a while, like two times a year, I’d get invited to lunch with Art. You had to be at the Four Seasons at 12:30 sharp. The second you sat down, vodka martinis, ice cold, are on the table. Art’s got an agenda for every lunch. He had an agenda. He’d usually write it out. He planned his day around lunch. He’d sit there in the morning planning what he was going to be talking about at lunch.

So vodka martinis with the first course, a bottle of Chalone chardonnay with the second course, a bottle of some red that was “Julian [Niccolini]’s choice.” As soon as you finish, Art’s like, “We’re heading to the bar,” because, after a while, they wouldn’t let him smoke at the tables anymore. You could still smoke at the bar. Light up a cigarette, have a sambuca.

And, at, like, three o’clock you’d get back to the office and just hammered. No choice but to put your head down and go to sleep for an hour.

Sean Plottner: Okay. How about art directors, in general?

David Granger: It’s difficult to generalize about art directors. I think it’s rare when there’s a perfect meshing of editor-in-chief and art director, and they’re equally important to the success of the magazine.

Many art directors have their own ideas about, especially magazine design, that may or may not be the best thing for the success of that magazine. But when an editor and an art director work beautifully together, as I did last 11 years at Esquire with David Curcurito, it’s freaking magic.

You’re just like dependent on each other. You make each other so much better. [That was] the greatest creative collaboration of my life. And that’s the potential of the editor/design director relationship.

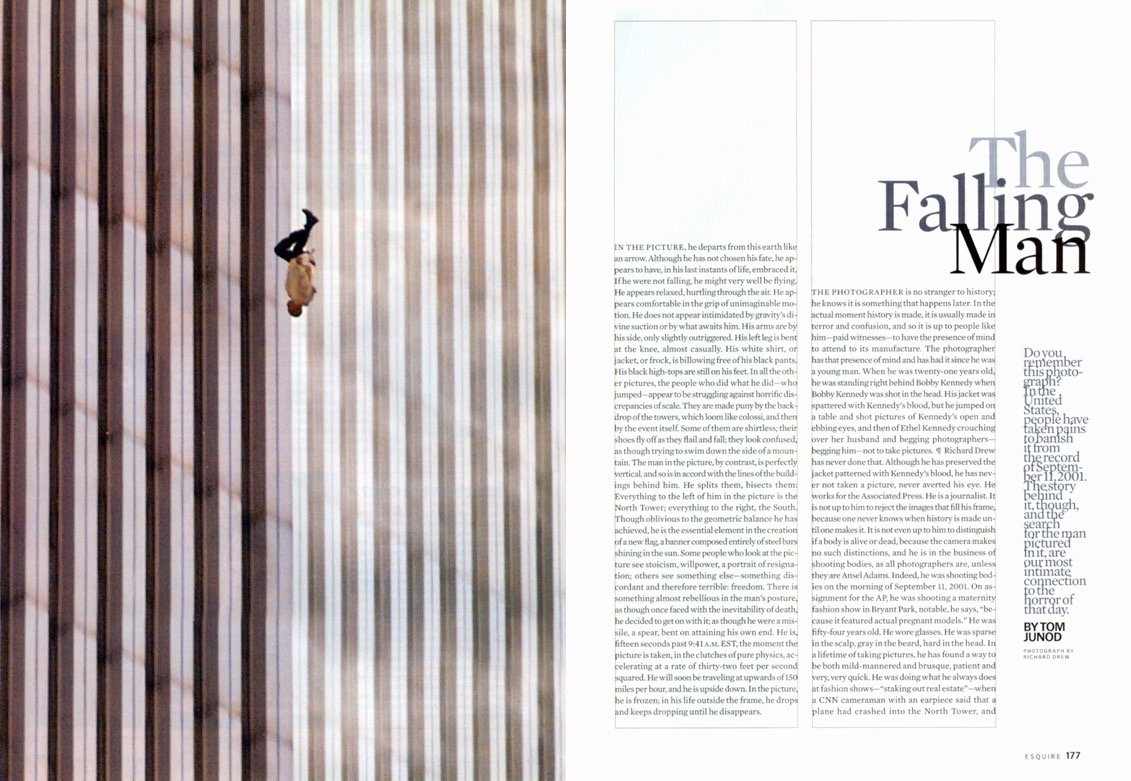

Sean Plottner: Great. A couple more. A quote of yours: “The spread is one of the great, maybe lost, art forms of all time.” The spread. The magazine spread.

David Granger: Yeah. I believe that there are many things that the internet just can’t do—like almost everything. But the design possibilities and the expressive possibilities of a two-page spread in a magazine are just limitless. You can do anything on two pages of a magazine.

I mean, you just, you take all the things that a magazine is made of, paper, ink, photos, words, ideas, design, and you just let them go crazy on two pages of a magazine and almost anything is possible. And there’s never been anything like that in any other medium.

Books don’t do it. There’s nothing like it on the internet, no matter how much they try to be interesting design-wise. Everything scrolls, but there’s never that work of art that’s also part of a living medium. There’s an urgency to magazines. They’re timely. And you create a timely work of art on two pages. Nothing else can do that.

Sean Plottner: There isn’t. Viewing a spread, the gaze of the eye is so different than looking at something online. The creation of a spread is so different than anything you would create online. The anticipation, or expectation, of turning a page—you don’t get that online. And I think there’s a real psychology that makes it interesting. And your notion of, like, front of the book stuff, making sure a page does more than one thing. Jeez, a spread, like you said, can do so many things.

Okay. The phrase “content creation.”

David Granger: Well, “content” is a word that I try not to use. I think it’s the dirtiest word in the English language, especially starting in the mid-aughts of this century.

It’s just like, “Content.” It’s like the great leveler. It’s like anything that fills up the space is of equal value. That’s what the word “content” means. It’s like, “We’re going to get some content and put it on this website.” What the fuck? You have, like, you have articles. You have photos. You have great pieces of writing. It’s not “content.” It’s something that somebody slaves over.

But that’s the mindset. It turns out that the medium is the message, right? If you create something that’s designed to be read quickly, whether it’s on a webpage, or social media, or whatever, it’s going to suck more than something that is designed to move somebody and make them rethink the foundations of their life.

And a magazine has the potential to create a work of art, a timely work of art, that’ll have a profound effect on somebody.

Sean Plottner: Okay. Awards. You’ve got a few.

David Granger: Yeah. They’re nice. They make you feel good. I have this Polaroid of myself sitting in an abandoned folding chair on Eighth Avenue holding one of those National Magazine Award statues.

That’s one of my favorite photos. We had 17. They were on display in the Esquire offices, and on my last day there I stole one just so I could have one. So I guess they mean something to me.

Sean Plottner: How many of those Ellies can you fit into one briefcase?

David Granger: I just took one. I don’t know. I don’t even remember what I took it out in. But you can’t plan to win awards. You just try to do really good things and then every once in a while it happens.

Sean Plottner: Okay. The slogan “Man at His Best.”

David Granger: Yeah. So for a long time, Esquire, its slogan was “The Magazine for Men” for most of its life, like, up into the late seventies. And then when your boys, Whittle and Moffitt, took it over, they changed it to Man at His Best. And there was a reason for that.

As I said before, Phil Moffitt, he had a mission in Esquire and he was well ahead of his time in that he was really into yoga back in the seventies and eighties, and he believed in the possibility of personal improvement and that was one of his main goals for the magazine.

Kind of like my Martha Stewart moment, he wanted to help people improve their lives and he changed the slogan of the magazine to Man at His Best. And when I got to Esquire, I think they’d gone back to The Magazine for Men, and I know that they’d scrapped Man at His Best. And as soon as I could, I changed it back to Man at His Best in homage to Moffitt, but also because I wanted it to express part of our intention for the magazine.

Sean Plottner: I guess I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask at least one fashion question, and I’m not one to delve into fashion, but you know, I think you’ve got some experience with it. What’s the best men’s fashion tip you learned while you were at Esquire?

David Granger: That’s a hard one because, when I was at GQ, Tom Junod wrote this piece called “My Father’s Fashion Tips.” His father thought he was Sinatra and he had very strict rules about fashion. And the piece was built around five of his father’s fashion tips. And the one that stands out to me the most is Always wear white to the face. It just shows off your face. Your face is your greatest asset.

Always wear white to the face. It’s like, “Put a spotlight on your face.” But almost equally relevant and true is another of Lou Junod’s fashion tips is, The turtleneck is the most flattering thing a man can wear. This is true.

I mean, in Esquire I learned a lot of the details, I learned a lot of the history, but I started being aware of what I wore when I was working at Sport magazine, I saw a picture of myself sitting in the dugout with Dave Parker, the great Reds slugger, and I was wearing, like, some shitty blue pants and a shitty checked short sleeve. And I realized, “Man, no wonder athletes hate sports writers!” You know? And from that moment on, I decided that I was going to dress at least as well as the people I planned to meet that day.

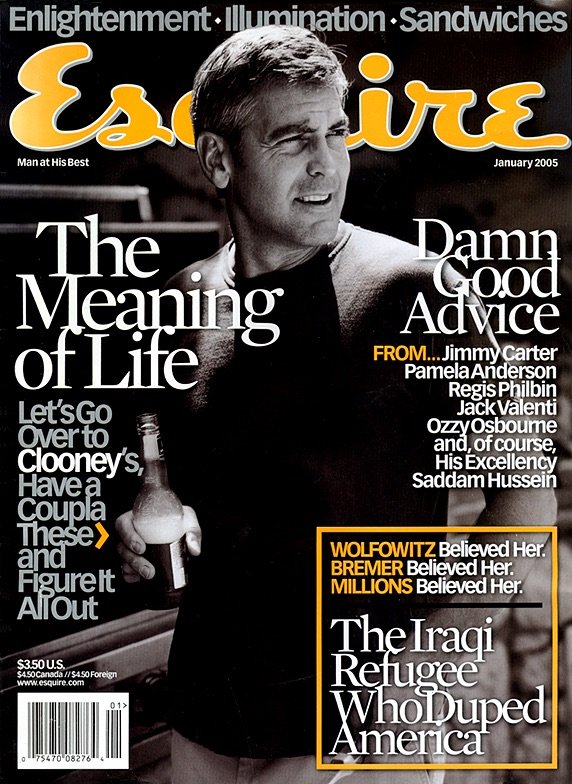

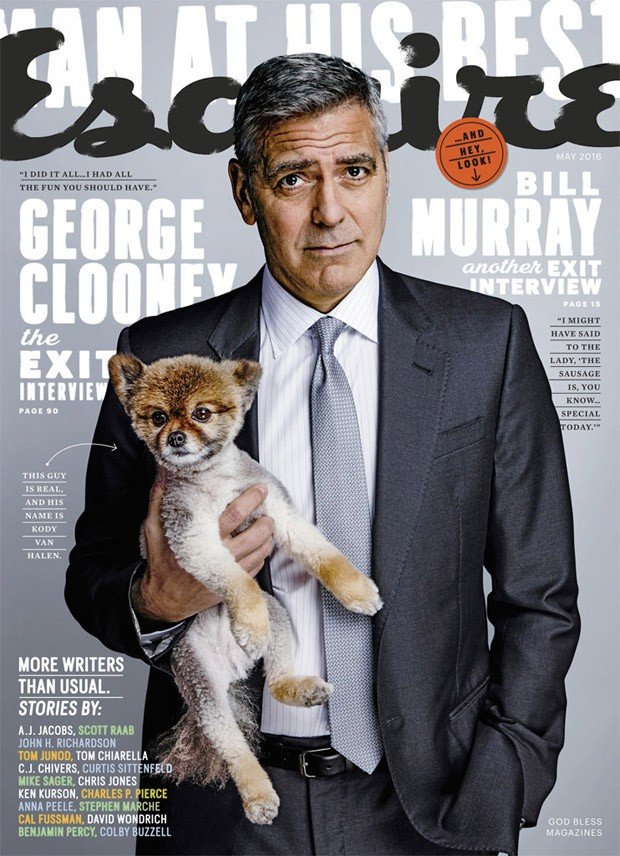

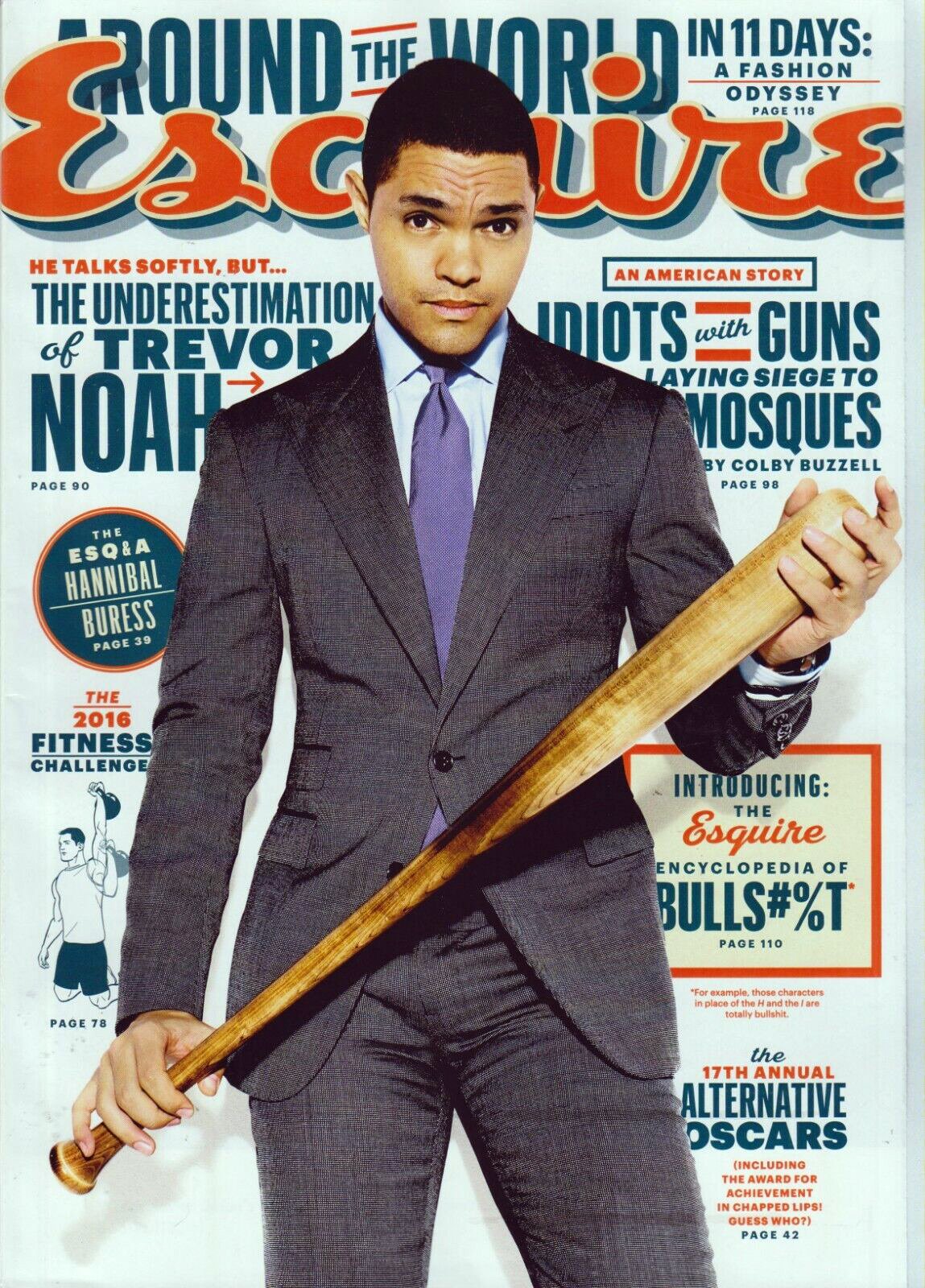

Clooney on the cover? That doesn’t suck. The superstar actor appeared on eight of Granger’s issues.

“Covers always suck. They suck and they suck and they suck until they don’t. At some point they stop sucking.”

Sean Plottner: Well, I’ve got to tell you, I’m very glad you didn’t show up today with a tie and a jacket on. Okay, thank you. Let’s move into really my final section here, the section of Today and the Future. What’s wrong with the magazine business today?

David Granger: What’s wrong is that everybody lost faith in the vitality and vibrancy and validity of the medium. And that started with the magazine companies. You know, when everybody went running toward the inevitable payday that was the aggregation of content and gathering a huge audience and believing that advertising would flow if you just presented a large audience to the world. Everybody ran in that direction.

Hearst, Condé Nast, Time, Inc. They all abandoned their print products and started investing in digital because, of course, digital was the future. Even though there were already players who were going to kick their asses, who were dominating that space. It’s like, if you can’t win the game, play another game. And they abandoned the game that they were good at.

And so that filters down to everybody. When the business side is shaky, editors and writers are less likely to take chances, editorially, right? Because you do something that gives a fence to an advertiser or to readers, and you’re putting the viability of the business at risk. So that’s a big thing.

But then the rise of social media and the fact that everybody has a platform that has the potential to spread worldwide in an instant also makes editors and writers a little scared. It takes a lot to stand up to the mob when somebody decides that something one of your writers has written is offensive in one way or another, or racist, or sexist, or whatever.

And the ability to stand up to that sort of invisible mob is hard. And it causes a lot of people to play really safe. There are a lot of pressures on magazine editors and writers to play safe. It’s the same in most media. It takes a lot more courage to stand up for what you believe in, in the highest forms of expression now than it did when I was an editor-in-chief.

Sean Plottner: Well, you know, we’re on a podcast called Print is Dead. (Long Live Print!), and sometimes my thinking is, you know, “Geez, the magazine business is long gone.” But there are still some great magazines out there that are, first-and-foremost, print magazines. New York magazine is still excellent. The New Yorker. I think the new Sports Illustrated works. The Atlantic. On and on. They’re still there. They still come in my mailbox. Is there ever a chance we’re going to see more magazines? Or a revitalization of the industry?

David Granger: It’s hard for print to be as vital as it was because there’s not a robust advertising base. And for better or worse, mostly better a long time ago, and worse more recently, advertising was 85-90% of magazine’s revenues.

So advertising goes away and you don’t have the pages, you just don’t have the resources to do what could be done in the nineties and the early two thousands into the 20-teens. And, it’s just, it’s hard.

I love it when I see little magazines popping up. I got to help this magazine—Racquet, which is this high quality tennis magazine—I got to help them get started, and I’m amazed that they’ve been able to sustain it. But they sustain it not through the traditional magazine metrics of advertising and circulation. They mostly sustain it through doing events for advertising partners or for folks with a lot of dough.

And so that’s a little different. And it’s also a reason not to give offense. When you’re being sustained by your sponsors, it’s a little harder to do anything that’s really risky. There’s always going to be great magazines.

Every year I judge the City and Regional Magazine (CRMA) contest and there’s always really good, really surprising stuff. And a few years ago I went to one of their conventions, and there are just as many city regional magazines, I think, as there were 15 years ago!

I know a surprising number of writers, surprising to me because I’m ignorant, that the authors I’m working with, like, at least two or three of them right now are doing pieces for alumni magazines. And there’s a vibrancy there. And you guys actually pay enough money that writers want to spend some time doing that. Which is often hard to do with commercial magazines to make a living.

So yeah, there’s always going to be room for magazines to thrive. They’re just not as big a force as they once were. And it’ll be very hard to make them that.

Legendary comic artist Chris Ware’s version of “What I’ve Learned”

“The design possibilities and the expressive possibilities of a two-page spread in a magazine are just limitless. You can do anything on two pages of a magazine.”

Sean Plottner: That’s very interesting what you say about alumni magazines. As a longtime alumni magazine editor, it is a different animal than the consumer magazine world. And I think that the talent that’s available to those of us running alumni magazines is greater now because there’s less consumer magazines for these people to go and work at. And we do have some money. And I think things have gotten better.

What is really great in the research that we put out to our readers is they’re not saying, “We don’t want print. We want to read it online.” They want their print magazine. And it’s almost a luxury these days. And again, that’s conflated with a lot of emotions about their school and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. But the love of the print magazine—it’s there. And it’s cool to see.

David Granger: Yeah, it is there. But I remember doing focus groups and it’s there to a level. And I remember watching readers go, “Man, I love Esquire.” And they would know particular writers, and they would remember specific pieces, and they would talk about the things they love in every issue. And then at the end of the thing, the guy would say, “So are you going to resubscribe?”

And he’d go, “Uh, I don’t know.”

When it comes to going into your pocket for $15 or whatever it is, that’s not that much money, but there’s some weird disconnect there.

But you’re right about people’s love for print. I see that in the book business. All the growth in books over the last 10 years—it’s exploded in the last two and a half—is in hardcover sales! Audio books are growing slowly, eBooks have completely flattened out. Together they’re only like 12% of the book market. And hard covers are where all the growth is. And there’s something that people like about that.

Sean Plottner: Yeah. Well, I understand that. I love having a book in my hands, and eBooks aren’t the same. Tell us what you are doing now, speaking of “long live print.”

David Granger: Yeah. I work in the book biz. I’m a literary agent. I’ve been doing that for six years, and it’s been good. It’s been good. The thing that struck me after getting tossed out of the magazine business, was when I started having meetings with book people, there was, especially at the executive levels, there was, like, a genuine optimism and I hadn’t felt that in the executive levels of the Hearst Corporation for a long time, with regard to magazines.

And so it was refreshing that top editors and top executives could see that they were in a growing business. It’s not a huge business, but it was a big business. And growing. And so there’s optimism and there’s willingness to make investments. They’re running scared in certain ways too, but it’s a business where its leaders know there’s an upside and that was refreshing for me as somebody who wants to catalyze creativity.

Granger’s last few issues at Esquire

Sean Plottner: Can you share a project you worked on or are working on now?

David Granger: Yeah. I could bore you to tears for, like, several minutes.

Sean Plottner: What’s the most exciting project you’ve worked on since you left magazines?

David Granger: Can I give you two? Okay. The first one, that was probably the most fun, and it made me feel like I was part of the cultural conversation, was we got chosen to represent this guy, Andrew McCabe, who was the deputy director of the FBI.

And then Trump savaged him and his wife and fired him. And I got chosen to help represent him. And as soon as we got the gig and won the beauty contest, I flew to DC and spent two days with Andy in his living room and just interviewed him and started writing the proposal, and then we ended up turning it over to a writing team.

But we did the book fast, we got it out in a timely manner, and it hit number one on The New York Times bestseller list, which is tons of fun.

The thing that I’m most excited about right now is that three of my writers have written a novel that is the funniest, most intentionally offense-giving piece of writing I’ve read in a very long time.

It comes out November 8th. I don’t know what else is happening on November 8th. There may be, like, some election going on or something. But I think the event of the day is that The Lemon—it’s called The Lemon by S.E. Boyd—is publishing on November 8th. And it takes shots at everybody who deserves to have shots taken at it.

It’s set in the world of high-end cuisine, but goes quickly into the cynical world of big-time media and the fame industry, the celebrity industry, and it’s just, it’s hilarious. You zip right through it and it’s fantastic and it’s made, like, “Fifteen Books You Have to Read This Fall” lists, and gotten amazing advanced reviews.

I just hope when it comes out, the reviews are as fantastic as they’ve been so far. But anyway, it was great working with three authors and creating a pseudonymous new author, and creating a book that I think is going to be very successful: The Lemon by S.E. Boyd.

Two of Granger’s latest book projects

Sean Plottner: Got it. You sound very engaged and into what you’re still doing.

David Granger: It’s fun, man.

Sean Plottner: Okay, we at Print is Dead. (Long Live Print!) have learned that when Steve Jobs died, he left a gazillion dollars that he wanted David Granger to use to create a magazine. Apparently you were on his radar screen, we have no idea. Maybe it was that digital cover you did. Anyways…

David Granger: No. He blackballed us from ever getting advertising. We were blackballed for 12 years, during Apple’s biggest growth spurt, from ever getting a page of Apple advertising.

Sean Plottner: He never gave Esquire credit for the fact that he knew turtleneck was the best way to go every day? Okay, so you got oodles of money to do a print magazine. What would you do?

David Granger: That's such a hard question. There was a time that I really wanted to do a magazine called Magasin.

Sean Plottner: Terrific title.

David Granger: It harkens back to the French word for department store, which I believe is magasin. And it’s just, like, it’s got a little bit of everything. But, kind of the best of everything.

And if it was stipulated that this money was to go to creating a magazine, I think I would create Magasin. And I know who I’d want to be my business partner in it, but I would need so much help at the digital and social aspects of making a print magazine successful that I’d be a little daunted. I have to find just the right person.

But yeah, I think I would create Magasin.

For more on David Granger, visit his website.