One Eye on the World

A conversation with editor and founder Tyler Brûlé (Monocle, Wallpaper*, Konfekt, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT COMMERCIAL TYPE

“When life itself seems lunatic, who knows where madness lies? Perhaps to be too practical is madness. To surrender dreams, this may be madness. To seek treasure where there is only trash. Too much sanity may be madness. And maddest of all, to see life as it is, not as it should be!”

— Don Quixote de la Mancha

Monocle, the brainchild of the expat Canadian magazine maker, Tyler Brûlé, was born in early 2007, a relatively awful year for the magazine business, not to mention the entire world. In that year alone, more than 100 print magazines folded—or, as Wikipedia terms it, were “dis-established”—among them: Life (yet again), Premiere, Red Herring, House & Garden, Jane, Child, and Business 2.0. Months later, the global economy was hit by the Great Recession.

But Brûlé was coming out from under a rather lengthy non-compete agreement with Time Inc., after selling his previous startup, Wallpaper*, to the American media giant, and he was desperate to get back to the newsroom.

Given the times, and the stream of fading print publications, one could judge Brûlé’s resolve as “madness,” as Don Quixote cried in the opening clip. Digital was all the rage, the iPad was knocking on the door, and the radiation of the frenzied dotcom meltdown was still slowly killing legacy media.

“Madness”? Not if you know Tyler Brûlé.

In his world, “life as it should be” is rich—a morning espresso in a bustling cafe with a crisp newspaper written and edited in the romance language of your choice, sorting out weekends skiing the Alps or lounging on the Med while riding the night train to Vienna.

And then there’s the print—not only the magazine itself, printed on “upwards of nine different paper stocks, crammed with extremely niche articles about carbon-neutral airlines in Costa Rica and sleek Afghan restaurants in Dubai,” but also special edition newspapers, coffee table books, and Monocle-approved travel guides.

(Someone forgot to tell Brûlé and his brilliant team of collaborators that print is dead).

In a media culture traditionally obsessed with scale at any cost, Monocle’s modest 100,000 circulation belies a thriving multi-media juggernaut that confidently ignores the lure of social media. “We’re in a very fortunate position that we’re an independent publisher,” says Brûlé, “and we don’t have the commercial pressures of a big parent. And those commercial pressures can be two-fold: One is cost savings, but the other pressures are to go and chase after every new trend.”

In fact, Brûlé thinks of Monocle as a family business.

“We don’t set out to be pioneers, but also we’re a family company, and we can choose to do things quickly if we want to.”

That same culture has manufactured the pressure to establish one’s entrepreneurial cred. You’re not the editor, you’re the founding editor, the founding creative director, the founding director. But when asked about how he thinks of and refers to himself, Brûlé answers simply:

“If I think about ‘What do I do?’ I’m a journalist. I’m out to be a witness. I’m out to absorb, I’m out to interpret, and I’m out to communicate.

A print-centric media phenomenon, created as a family business, led by a journalist. Surprising? Not for someone who’s been building a life—as it should be.

Here’s our editor-at-large George Gendron with Tyler Brûlé.

Monocle’s premiere issue, March 2007

“Print is absolutely at the core of what we do and we’re unapologetic about that. ”

George Gendron: I have what might sound like a kind of juvenile question I want to begin with, but I know a lot of people would love to ask it if they were here in my place. How cool is it to be Tyler Brûlé?

Tyler Brûlé: I think it was cooler—and maybe that was when I was in my I still think I’m in my publishing prime—but maybe it was cooler, like we all were, when we were in our late twenties, early thirties, or something like that. But it’s still okay. It’s all right.

George Gendron: What do you mean in your “publishing prime”? You guys seem to be kind of peak performing for some time now, it seems to me.

Tyler Brûlé: I feel I still am in my publishing prime, a different phase of it. But no, listen, [it’s] all good. All good. Just not sure how “cool” it is, maybe. I’ve been living with it for a while. Yeah, maybe that’s it. We can come back to that.

George Gendron: Where are you right now, geographically? You travel 250 days a year, so where are you now?

Tyler Brûlé: Right now I am standing in the middle of our—we call it our “lounge space” at our headquarters in Zurich on Dufourstrasse 90. We have a wonderful setup for doing all kinds of audio, but also all kinds of events as well. And Dufourstrasse 90 is where you’ll find a beautiful little kiosk and a great cafe and bar space, and a little Monocle retail area, and a Trunk Clothiers (the menswear retailer owned by Brûlé’s life partner, Mats Klingberg) shop.

And on the top floor of this building you’ll find the headquarters for all of our global operations, our holding company, which owns a vast chunk—the majority share—of Monocle and our agency business. So this is, let’s call it home. You’re speaking to me from what has become our home base for the last five years now.

George Gendron: That raises an interesting question. If I didn’t know that you were headquartered in Zurich and somebody said to me where do you think Monocle is headquartered? I would’ve said London, Berlin, I don’t know, maybe Tokyo. But Zurich? I don’t know Zurich well, but I know Geneva and I have to say, I find those cities boring.

Tyler Brûlé: Oh, well, I guess you haven’t been to Zurich for a while. And maybe this goes back to your earlier question about “coolness” and all of those things. I sort of liken Zurich to Berlin for people over 40. It has all of the things that you want in terms of entertainment and evening delights and weekend fun times, et cetera.

But unlike Berlin, it has an airport that will connect you around the world. Maybe it doesn’t have the cyclist anger that they have in Berlin. It’s a happier city. There’s a better disposition here, so please return. And it’s also a city which is home to one of the world’s oldest newspapers, which still continues to innovate and buy up interesting things. So, as a media city as well, it’s a very interesting one.

George Gendron: That’s interesting. I think for some people, maybe many, that might come as counterintuitive. It always struck me as I think of Zurich and I think it’s one of the more expensive places to live, period.

Tyler Brûlé: It is, but I would say there’s a value for money that comes with it. There’s, I would say, a certain intellectual liberalism. There’s something going on here in media where the newspapers print things which would be unprintable on your side of the Atlantic, where there’s a proper, healthy debate that doesn’t get shut down.

We’re talking about journalism and we’re talking about print on this program, and there’s a real vibrancy here. And I find that exciting. We’ve got two newspaper groups down the street from us. I mean, one is really at the end of Dufourstrasse, which is the NZZ, which of course, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, which is one of the oldest newspapers in the world.

You have the headquarters for Ringier Publishing. They do the tabloid Blick as well, and not far away you have another major Swiss media group as well. And for a tiny country, albeit a very rich country—and this is obviously one of the richest cities in the world—it should not surprise that there’s quite a bit of innovation going on.

But of course, in Switzerland it all happens in a rather hushed, quiet way as well.

Monocle launched its annual Quality of Life Conference in Lisbon, Portugal in 2015.

George Gendron: Yeah, that’s a good point. Let me switch gears here. You and Monocle have attracted more than your share—you could argue more than your fair share—of snark and much more glowing coverage of the magazine itself. But I wonder, maybe this is just my point of view and so correct me if I’m wrong, but I wonder whether, even now, journalists in particular really understand and appreciate the sheer originality of your media model. It’s really the first 21st century sustainable print-plus model of its kind. And people don’t talk about that much.

Tyler Brûlé: Yeah, maybe because people don’t talk about print that much anymore. Aside from where it’s being discussed, maybe in podcast forms like this. But maybe it’s also just the nature, of course, where the media conversation has shifted.

Because I think when I look around the world, there’s still many amazing things that are coming out on page where you still have incredible centers of where, I wouldn’t say it’s necessarily flourishing, but where you have a lot of new titles coming out. And I think about our neighbors around here, particularly the French—every time I’m at a French train station or at the airport where I’m in front of a French newsstand, I’m amazed that there’s always something new that I haven’t seen.

And yet I just came back from a big tour of North America and, as we know, at many travel points, the newsstand, the kiosk has completely disappeared. Or if it is still there, there’s nine titles for sale. And none of them are new. So, yeah, and I guess going back to us, yeah, people probably aren’t discussing us that much because there’s not many column inches being devoted to talking about magazines these days.

George Gendron: But what strikes me—I shouldn’t say “but”—and what strikes me as interesting and profoundly disappointing is that no one seems to have learned anything from what you guys have done.

Tyler Brûlé: Well, I don't know if that’s entirely true. I think there’s a couple of annoying titles out there which look to us and ape many things we do. And I don’t need to name them because they know exactly who they are. I do hear from the media grapevine that people take a copy of Monocle and they say, “Can you make our annual report look like this?” Or they take a copy of Konfekt and they say, “Could you create a similar magazine in Polish for us?”

So it is happening. But maybe what you’re driving at is the totality of our business model and how we function. And, of course, print is absolutely at the core of what we do and we’re unapologetic about that as well. I think that is one thing which is very different.

I think so many legacy companies, call them what you will, venture into an advertising meeting, a partnership meeting, whatever it may be, and they talk about, “Well, we’re digital first, but we still have a print business.” We’re completely the opposite. Like, we have a very solid and growing print business in all its forms.

The main magazine, newspapers, books, special editions, pocket books—whatever it is, we’re buying more paper than we’ve ever bought before. What’s interesting is that our partners—and those can be governments, they can be luxury brands, they can be airlines—people are looking for, I mean, I could even say even ministries in certain countries that are focused on AI still want a piece of print. Which is kind of remarkable.

But I think that’s partly because there’s a confidence about it. We believe in what we do and we’re not looking around the marketplace or looking around the room talking about other products. We’re talking about what I also see as super-core to driving the profits for our business as well.

George Gendron: And when you’re talking about non-traditional publishers—they’re governmental, whether they’re academic, whether they’re corporate—I still think there’s maybe an understanding about the power that print has to brand that still seems to be lacking in digital.

Tyler Brûlé: For sure. And we scratch our heads sometimes wondering, how is it that you can be speaking to a big technology company, a company which puts innovation, digitization at the forefront and you bring them a variety of ideas—and this has happened on a couple of recent occasions where just such a company, which is a global leader in engineering, and you bring them films, and you bring them a podcast idea, and you talk about events, and big digital partnerships, all within the Monocle realm—and they just pick up the magazine or they’ve come across another print spinoff that we’ve done and they say, “But this is what we want. We love all of those digital ideas, but actually we like this on page and we actually feel that this is true innovation.”

And I think we get back in the car after these meetings going, “Wow. Incredible.” When you look at the mission of what that company is, which is about trying to move away from cutting down forests and trying to be sustainable in so many ways, but yet they actually come back to the printed word.

And increasingly, I’m not sure if it’s boardroom gymnastics that drives it because I was also thinking there’s a certain commoditization of course that comes at a corporate level. If you have to go to your quarterly meeting and present to the board, alongside all of the other people who happen to be C-suite executives, maybe there’s an advantage to being that one person, because you’re in marketing, you can actually leave people with 10 copies of something that you partnered with Monocle for and that’s what you leave the room with because everyone else is presenting on the exact same screen.

And so there is this commoditization, which comes with digital in general. And there’s a way that print allows you to continue to stand out.

“There’s not many column inches being devoted to talking about magazines these days.”

George Gendron: Let’s talk about Monocle, the magazine, for a second from a variety of different perspectives. And I guess I’d like to start by saying you meet somebody—I think I’ve heard you interviewed where this came up—you meet somebody, and shockingly they’ve never heard of Monocle. If you didn’t have a copy handy, how would you describe Monocle, the magazine, to someone who’s never seen it before?

Tyler Brûlé: I think we talk in terms of—I guess we have to speak of the physical nature. I talk about something which is bookish. I say, “Don’t think of a magazine as you know it today. Think about something which is much more bookish and has loft and heft to it in format. Think about something which is going to challenge and surprise you, something that’s going to take you around the world.”

We started in the very beginning—if I look back, to 2005, 2006, when we were just really trying to whip this thing into shape, 2007 when we launched, we talked about this briefing on global affairs and business and culture and design. And we still use that. That is what we are.

And I think that has also become an extension of the medium we’re in now with our radio business. Certainly with our books business as well. But going back to the core product we do feel it is this global briefing and increasingly we’ve been speaking in terms of also just being a companion. This is something which you live with all month. Hopefully you live with it for a lifetime because there’s a whole other world of people who have been with us for 17 years, or going on 17 years, and they wonder, “What do I do with my collection of Monocles?”

I think there’s room for an adoption agency right now, because people might be downsizing or they're moving around the world—it’s a lot of magazines to ship. But they don’t want to put them in the bin either.

So I think we’ve gone from being this briefing, I think, to also a daily companion for people. And I’m not just talking about what we’re doing digitally, but I think also in the core print form.

George Gendron: So you’re reviving bookshelves, basically.

Tyler Brûlé: Sure. And that’s actually why we have a very small bookshelf business with the Swedish brand String. We just did a little capsule collection of more of a bedside bookshelf, but shelf nonetheless. You can hold two years worth of subscriptions.

George Gendron: Let’s go back to the early days of Monocle, in fact pre-Monocle, when did the idea first occur to you?

Tyler Brûlé: I mean, we could go way back. And we could go way back to pre-Wallpaper* days when …

George Gendron: Yeah. Go back.

Tyler Brûlé: … I was working for a variety of different titles, writing for Stern and Die Woche in Germany and writing for Vanity Fair and a variety of different titles. And I used to have one of those cellophane binder-folders. And I used to just pull out what I felt were great-looking news pages, what I felt were just great Q&A pages, and go and tear out wonderful reportage I might have seen in Der Spiegel or something. And I would actually just play. Sort of assembling this magazine, putting all these pages in between cellophane. And I still have those. They’re sitting in an archive somewhere.

Monocle’s “radio” station features an array of programming.

And that goes back to the early nineties, ’92-’93—a good three years before we actually launched Wallpaper*. So there was always this idea of doing something which was newsy, and global, and had an aspect of business to it, and wanted to be out there in the world on the real front lines, and also the front row in fashion.

And that was something I thought about for a long time, but somehow Wallpaper* got in the way in the meantime. But I would say that Monocle, as it is today, really is the magazine I always wanted to do.

George Gendron: That’s interesting. I don’t think I’ve ever heard that the idea from Monocle actually predated Wallpaper*.

Tyler Brûlé: Yeah, for sure. And I realized at the time, this is the magazine I would love to do someday, but I didn’t know if I would just happen to land in a position to be a deputy editor, to one day become an editor, to convince a publisher to make it happen, or would I end up doing it on my own and be the publisher and the media owner.

It turned out rather differently because I think, early on, I saw myself as being an employee rather than the employer.

George Gendron: Oh, that’s interesting. I want to get to that in a minute, by the way, kind of magazine-maker/editor versus entrepreneur. But I do want to follow up the question about where the idea for Monocle came from with a different one, which is how fully-complete was your vision for Monocle when you launched?

And I ask that because Patrick and I have unearthed your original editor’s note where you say, Be a complete media brand with print, web, broadcast components. And you go down a list of, I think, 10. Open bureaux, so we have our own people on the ground. Not be given away for free.

Another one, which I love, which is: Be an oasis from celebrities and low production values. Do our bit to raise the bar. How complete was your vision for Monocle when you launched, and how much of it has developed organically since you launched?

Tyler Brûlé: It’s fascinating when you read those things back because I think it’s a manifesto that we continue to live by. And I haven’t heard those words for a while, but I can certainly remember thinking about the early days when we were having a conversation, of course with distributors and potential advertisers.

And that was, of course, that was part of the pitch. And I think we still come good on that. I don’t think you see a lot of celebrities gracing our pages, and we’re still committed to opening bureaus and having people around the world, and we believe in actually having people in offices with our own name on the front door as well.

So, yeah, I think that we’ve stuck to that vision. Of course we’ve expanded around the edges. We are broadcasting because we are running a radio operation now. We’re not doing maybe as much television as I thought we might have been up to, but watch this space. We might be back. Let’s see.

And I think there’s always been this commitment to making an effort on page, or making an effort when we do an event, or ensuring that we are delivering the absolute best whatever we happen to be doing. And of course there are many components to the business right now.

But you know, I still feel we’re measured by what was the quality of our September issue or our December/January issue.

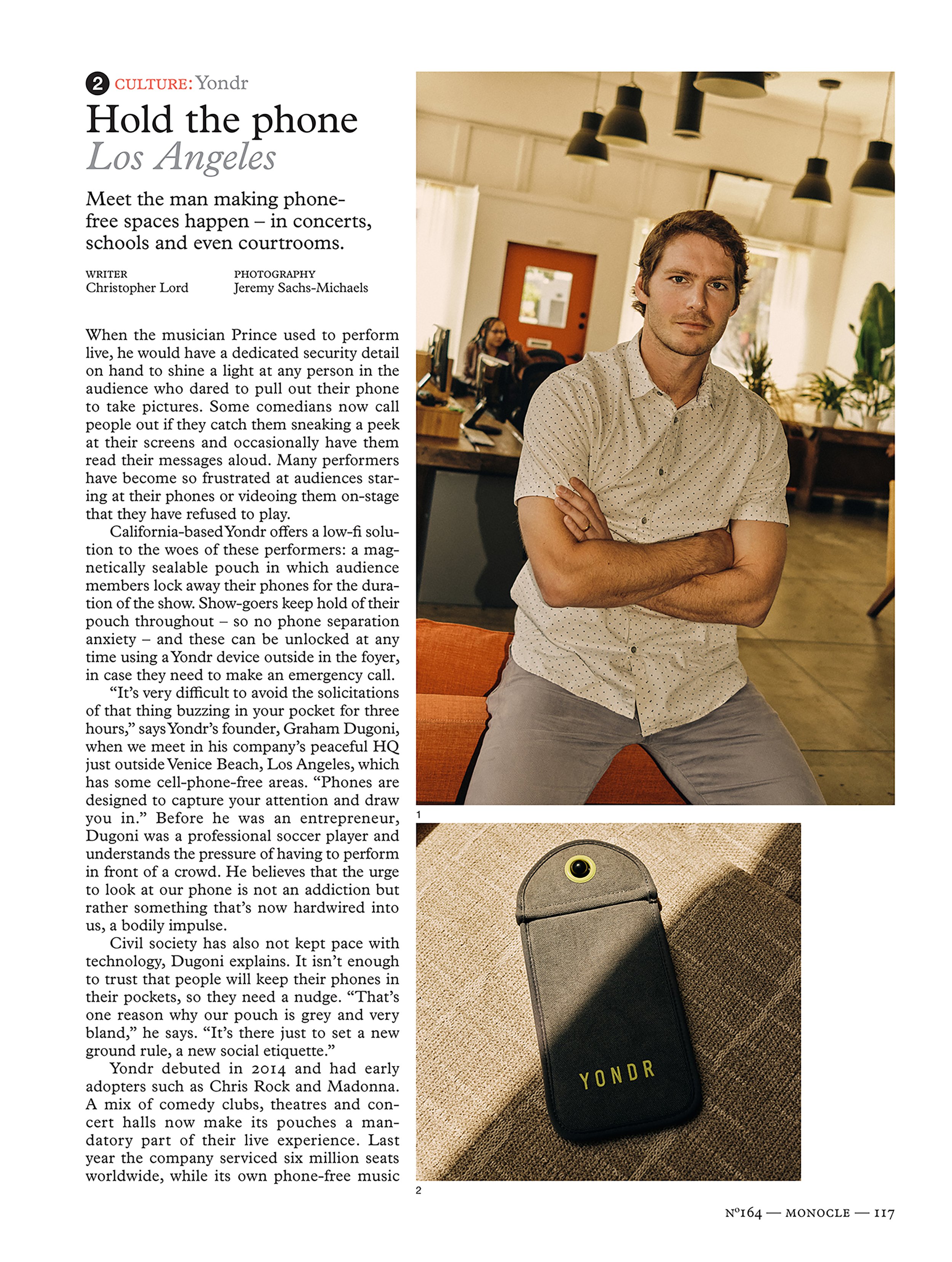

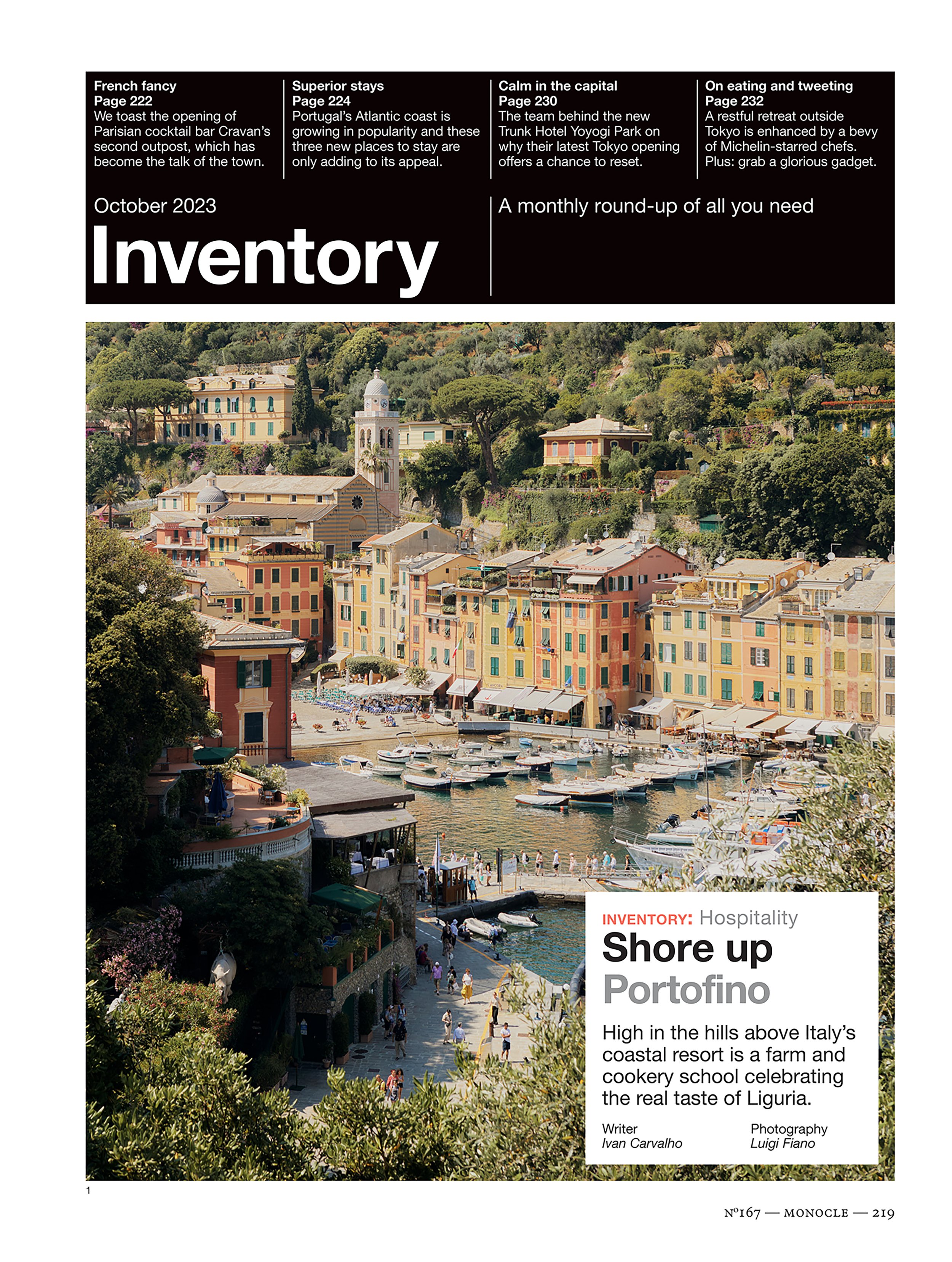

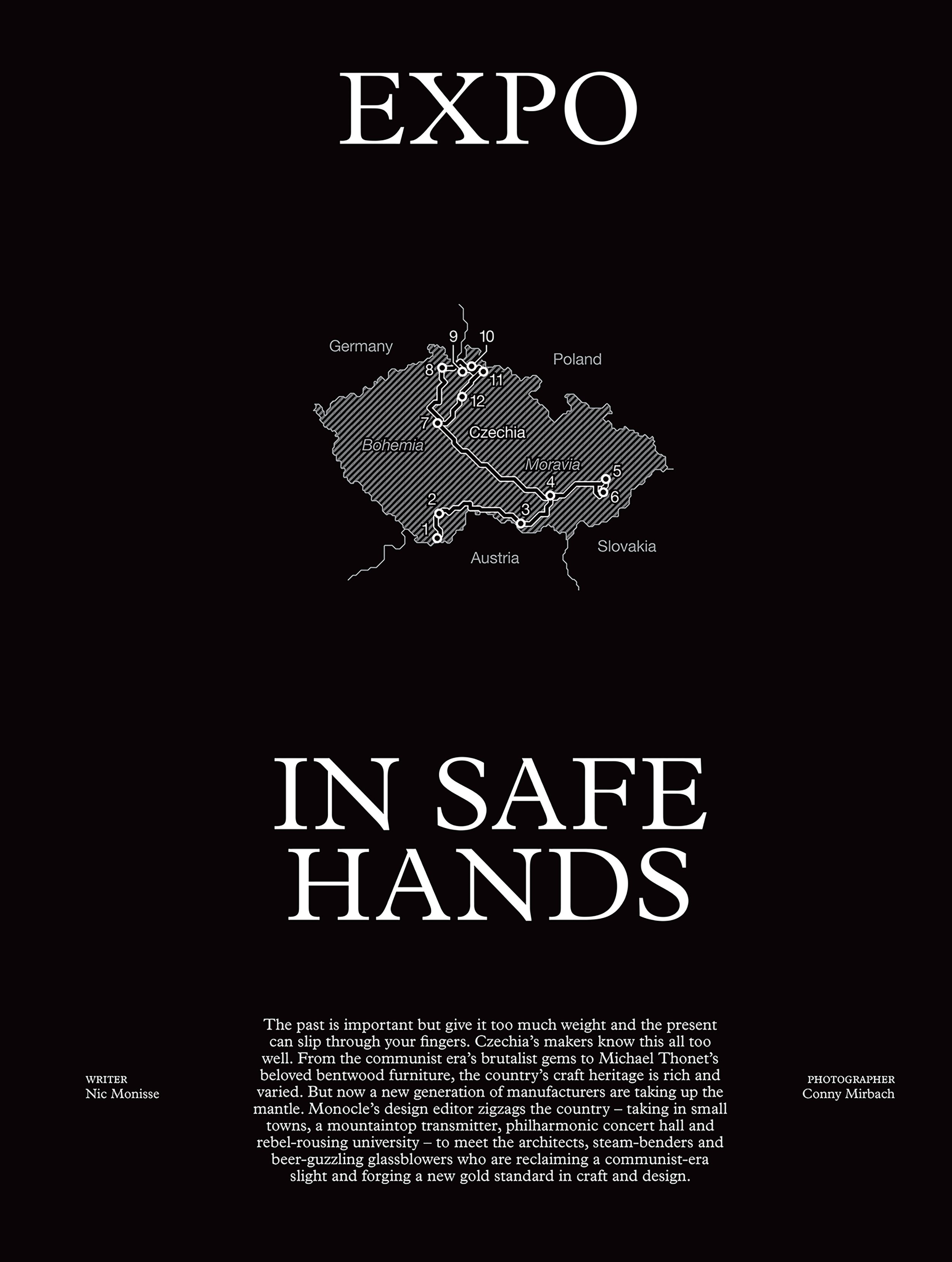

Monocle’s iconic design remains consistent across the entire enterprise. Below, a sampling of interior pages.

George Gendron: So it’s still the touchstone.

Tyler Brûlé: Absolutely. It’s what creates a discipline. It’s what keeps you—honest is not the right word—but it’s certainly what keeps you focused, keeps your eye on the mission. And I think it’s ultimately what you’re measured by. The newsletter part of our business is, of course, very important and becomes more influential, but I still think it’s the core magazine that comes out 10 times a year.

George Gendron: I want to bounce an idea off you and you may not agree with this, but here goes and I don’t mean to sound judgmental, but I’m just going to put this out there, which is one could argue that if you really deconstruct Monocle the magazine, there’s not necessarily anything quite remarkable about the individual elements—the typography, the photography, the illustrations, the content, the prose—each element seems professional, but not remarkable. And yet the magazine itself is remarkable. Patrick Mitchell said to me recently, he thinks of the magazine less as an exercise in traditional graphic design and more as an exercise in industrial design. Product design. Does that make any sense to you?

Tyler Brûlé: Up to a point it does. And I think part of it speaks to maybe our heritage as well, because we had a five-year pause between doing—and I say we, because of course, there’s a team that did travel with me from the world of Wallpaper* on to the world of Monocle—but there was a five year, sort of, rest or pause period. We were hardly paused, though.

And that was when we were really building up our branding and design agency. And we were working on other editorial products. But I used the word “product.” And many of these things— whether it was painting the fuselages of Airbus aircraft or it was working on retail projects, or it was indeed working on packaging—these were exercises in industrial design, graphic design, building and creating environments that happened to be on rails or had wings.

And so that was a really interesting period to go through, because I was all set, at the end of Wallpaper* to maybe just pause for nine months and then bring out a new magazine. But having five years in between, I think, allowed us to really think about brand, and development of brand, and the codes around brand, and what makes a good launch succeed or fail. So it was a very interesting learning period, which has definitely informed where we are today.

George Gendron: What’s interesting—I want to see if I can marry that question with something that occurred to me earlier, when you were talking, and that is your vocabulary is really interesting. You don’t talk about “podcasting”—you talk about “radio.” You don’t talk about “video”—you talk about “television.” Explain that to me. That’s clearly very intentional on your part.

Tyler Brûlé: Yeah, it’s either intentional or it’s lazy or it’s because I’m a child of the 1970s combination of all. Yeah, sure. It’s … I mean, listen … I think one thing that keeps you sharp— because I do try personally, and I think on our editorial floor we try not to fall into language traps that I think many people sort of swirl around in.

And I think we do have our—I come back to that notion of codes and a tone that we try to speak with. And it’s interesting when you go back to your earlier question about, where in the world, if you think about Monocle, where are we based? Are we London? Are we New York? Are we Berlin? et cetera. And I always try to say that we, we don’t want to be any of those places, but we want to borrow from the best of all of those.

And when we think about television or we think about radio versus podcasts, it’s because there’s an intention and there’s an honesty to it as well. We said from the very beginning, we were probably one of, again,”legacy” or we were one of the first, certainly, print brands to get out there with a podcast very early on.

But I would say within the second or third podcast, because we were making this program in a studio around the corner from Broadcasting House in London, I thought, “Imagine if we took this show on the road and did this 24 hours a day, seven days a week.” And so we were thinking about radio and we do talk about bureaus because that’s what they are. Because we do have people in cities with the support of their own office and the equipment they need to do their job.

And yes, is there a romanticism to it? Is that part of the nature of why the magazine’s called Monocle? A little bit. But you know, I guess I sort of see it as part of this is also—maybe it was a little bit of a correction as well. When we came out in 2007, many things were pointing south. And were pointing south and moving at speed.

I think back to 2007, what was happening in print then. We had the digital surge already happening in terms of digital photography. And look back at magazines in 2007, 2008, 2009, when there was that move away from film—reproduction houses, post-production, the printers—no one really knew how to deal with these digital files and, and just look at the skin quality magazines in that period, in a lot of magazines. It’s dreadful.

It looks like everyone somehow had a front row seat to some kind of nuclear apocalyptic sunset or something. And that’s why, in the very beginning, we—and we still take pride in shooting stories on film. Not to be Luddite about it. Not to be overly romantic, but there is a certain quality that comes as shooting on film still.

We don’t do every story on film, obviously, but I guess, part of the language and part of, I think when we think about how we want to position ourselves in the world and on the newsstand it’s, yeah, it’s to be correct, I would say.

Monocle’s special issues on the world, business, and travel

“We were probably one of the first “legacy” print brands to get out there with a podcast.”

George Gendron: I think there’s something really powerful about vocabulary that people miss. I mean, if I have to be part of another conversation where people start talking about “content.” Oh my God! How bland and generic can you possibly get when everything becomes content? And that’s why I find your vocabulary really interesting. Including “bureaux”, which is E-A-U-X, by the way. And there is a romanticism to it, but it has a really powerful effect.

Tyler Brûlé: Yeah, and I would say that doesn’t come from a whiteboard brainstorming session with a consultancy. It’s what we all believe. And I think that speaks to the people that have, that we’ve all stuck together for a long time. Not because we don’t have any other places to go, but there’s a commitment to the mission and what we want to, of course, deliver on page, the copy that we want to commission and edit, and hopefully turn into great editorial, as much as the types of evenings that we want to host for readers who are in Bangkok, or in Hong Kong, or in Asheville, North Carolina.

George Gendron: You talk about something that really interests me at a time when we have become, at least here in North America, absolutely obsessed with scale and scaling for its own sake. And that is, kind of, what seems to me almost like a filter you must use strategically to determine what you’re going to do to intensify the relationship, the intimacy between you and—I’ll call it a reader, but it’s a customer, right? Because they’re readers, their purchasers are your goods, they’re frequent attendees at your events, they drink coffee at your cafes. And it seems to me this notion of trying to do things to create and sustain an intimate relationship is so completely at odds with our obsession with scaling these days.

Tyler Brûlé: Yes, indeed. And it’s a conversation that we’ve had—I would say a lot—over the last three years. We’ve had many approaches from, of course, other media groups and private equity and many types of organizations with financial muscle in between those two who have just come in right away and said, “There’s so many things you can do to scale this business, and we can supercharge your circulation and your cafes and all the aspects of your business. And we can really give you ‘reach,’”… and all of the jargon that goes with this.

And as you’ve noticed, we’ve been very cautious, of course. And we can talk about, “Yes, we’d love to grow.” And it would be wonderful to be in a place where I didn’t have to sit beside someone on a plane who’s never heard of us before.

But of course, every day that also still means there’s a lot of opportunity in the world. But scaling at speed or just even scaling at a considered pace comes with dangers. And it’s not just about scaling in terms of audience and what does that mean in terms of what it’s going to do for revenues.

But I think also there’s the scaling that you might attempt with technology and there’s a scaling that might come with also to broaden your editorial reach, et cetera. And also the dangers there as well. And we’re not cautious, I think. We don’t set out to be pioneers, but also we’re a family company, and we can choose to do things quickly if we want to.

There’s many other things we can’t do because our pockets aren’t that deep. But I would still rather be in a position where I know the depth and scale and how far we can go rather than trying to bet the farm, because there’ve been so many instances over the last decade where we’ve seen people run headlong after the latest trend, whatever it may be. And we see the media world littered—the roadside is littered—with all kinds of carcasses of people who wanted to scale and they’re no longer with us.

How it started, how it’s going

George Gendron: Yeah, that’s absolutely true. And in fact, one of the things that interests me about talking to younger people, and I’m not going to break it down into Gen X, Gen Y, but is that there seems to be a sentiment among younger people that I find so encouraging that scale at any cost is the enemy of creativity. Period. End of story. And you could argue Monocle’s really interesting case study in that regard.

Tyler Brûlé: Yeah. And I don’t think we set out to be that brand or those people with their arms crossed over in the corner who don’t want to move. And...

George Gendron: Oh, no. I didn’t mean to suggest that.

Tyler Brûlé: No, but I’m just saying some people might think—and who knows, maybe there’s even a component of that. I don’t think so. But it is fascinating that there is that sentiment amongst younger consumers as well, who do want an intimacy, a conversation, who want to see the brand as “theirs.”

But at the same time, we know that of course we can be bigger in the US and we can do a much better job in many other markets around the world. But I also say the great thing is that we’re still here doing what we do and doing it on our own terms.

George Gendron: I want to take this opportunity to transition a little bit back to the young Tyler Brulé. It’s been reported that when you were young, you were mesmerized by a man by the name of Peter Charles Archibald Ewert Jennings. Now we know him as Peter Jennings, the anchorman. What was it about him that attracted you in the first place?

Tyler Brûlé: Well, when I was making the comment a bit earlier about being a child of the 1970s, I grew up in many cities across Canada, and there was a certain magnetism that the nightly newscast had for me growing up. And in Canada, unlike the United States—which is, I always think, is one of the defining differences—our national newscasts of record were never at dinnertime.

We didn’t sit down with our equivalents—Knowlton Nash, Lloyd Robertson—those were our Tom Brokaws, they were our Dan Rathers of the day. They were on at 10 or 11 o’clock at night. And I always found it kind of fascinating that the last word of the day, in terms of both domestic and international news, ran from 11 o’clock to 11:22 EST.

And so there was just something about that, sort of, bookmark at the end of the day, the look ahead into the next day. At the same time, of course, in the 1970s as cable came along, et cetera, and we were able to watch US channels, I was always fascinated, probably over the course of the seventies into the eighties to see how many of the names that I knew in Canada suddenly ended up at NBC, and CBS, and ABC, and of course, later on when CNN launched as well.

And I always wanted to, not always, but I would say certainly when I started my secondary school years, I knew that I wanted to go into journalism. I loved magazines and newspapers, but I saw myself in broadcast journalism. And then when I saw Peter Jennings jump across the border and become the foreign correspondent, and then really the face of ABC News, I thought, “This is the dream job.”

And especially in those golden years when you had ABC World News Tonight when it was anchored out of Washington and Chicago and London, that just seemed so modern. And it’s funny to think, Look where it’s all ended up today.

And I guess that goes back to the bureaus, and that sort of excitement. And it truly was. It did feel exotic. And you felt connected to something bigger. I mean, imagine now just to think that you’d be watching one of the big three networks, that that part of the newscast would come from the other side of the Atlantic. Kind of remarkable.

And that was the start of it. And that’s what I wanted to do. But here I am today not doing that.

George Gendron: And yet you could argue that portions of your career kind of did mirror Peter Jennings. You were a foreign correspondent. You were wounded in Afghanistan. And so again, there’s this kind of romanticism, I think, about your life and about some of the things and the people that inspired you that’s really quite extraordinary. But let me go back. Jennings started his career in radio, evidently, at the age of nine. What were you doing when you were nine years old?

Tyler Brûlé: Oh, when I was nine years old, I was—was I writing letters to the Ministry of Defense in Canada? Close to it. I think I was on the radio. I didn’t have a career, but I remember being on CBC Radio very early on with, I think, with the complaint because I felt that Canada’s defenses relied too much, or let’s say our poor defenses, meant that we relied too much on the United States. I think it’s still the case today.

And I did write a letter at one point to the minister and I told him that his selection of fighter aircraft was slightly misguided. Somehow it made it throughout the PR team at the ministry. But anyway, it made it to CBC Radio. And I can remember doing my first national radio piece—I must be nine or 10 or something like that—but I was quite young.

And it’s interesting when we talk about bringing up Peter Jennings today because, I have to say, I have Peter Jennings to also thank personally because I remember going to see a broadcast of World News Tonight in New York. And this would’ve been in the late eighties, I guess. And I ended up speaking to Peter afterwards, and he gave me a lift back to my hotel. And I was thinking at that time, God, to be in Peter Jennings’s limo and having a chat with him! And I said, “If you had one piece of advice for an aspiring young Canadian journalist, what would it be?”

And he said, “Get out in the world. Don’t go and work for a farm station in Canada.” He said, “You just have to get out there. Leave this continent. Go out, explore, take some risks, take some chances.”

And he didn’t say, “Don’t bother going to university.” But I think he almost said that in code, because he said, “As a journalist, you’re going to learn your skills and your skills are only going to be great based on what you’ve experienced and who you know.” And those are the words he left me with. And it was remarkable to have met him. And also of course have those words of guidance as well.

George Gendron: And obviously they had an impact on you, because that’s exactly what you did.

Tyler Brûlé: Yeah pretty much. Yeah. I certainly admired the man.

George Gendron: Who do you admire today?

Tyler Brûlé: Goodness. In the world of broadcast? Or just anywhere?

Monocle’s commitment to innovating in print led to the launch of seasonal newspapers.

“The roadside is littered with all kinds of carcasses of [brands] who wanted to scale and are no longer with us.”

Shortly after launch, Monocle began making coffee table books.

George Gendron: Yeah. It’s interesting to hear people talk about an individual who kind of mesmerized them. And I’m curious, are you mesmerized by anyone today that comes to mind? Journalists or not.

Tyler Brûlé: Sure. And just, like, on the fly at this very moment, I don’t think I’m mesmerized in the world of media by anyone in particular. But certainly I’m impressed, and have met many people that I look up to and like spending time with, particularly in the space of journalism.

And this is not to say that I’m blasé about it, it’s just because I think as we’re speaking, this has been one of these travel periods the last five weeks where I think I’ve been home for about four days. So maybe I could be a little bit sharper if we did this three days from now.

George Gendron: That’s okay. Well that raises an interesting question, which is—well first I want to ask you a big, broad question and then I want to pick up on your travel and on you as a magazine maker—and that is, which do you identify with more: founder/entrepreneur on the one hand, or magazine-maker/editor on the other?

Tyler Brûlé: I would even go—it’s not somewhere in between, and it’s not a step down—I would just say “journalist.” I still write for the newspapers. I, of course, write for my own title and I host programs. But it’s still driven by the foundations of being a journalist.

I always think the best measure is when you go into a country where you still have to jot down on a little yellow piece of paper “profession,” I write “journalist.” It just seems odd to write “chairman” or “editorial director” or “CEO.” It just doesn’t …

George Gendron: Yeah, I know what you mean. Of course.

Tyler Brûlé: But yeah, those are mainly functions, and I have those titles on various cards. But if I think about What do I do? I’m a journalist. I’m out to be a witness. I’m out to absorb, I’m out to interpret, and I’m out to communicate.

George Gendron: What I always love about journalism is it subsidizes one’s curiosity.

Tyler Brûlé: Absolutely. Especially when you have editors and publishers who are as curious as you and believe in the craft of journalism. And I have to say, I’ve been very fortunate over the decades to have worked with amazing publishing companies and outstanding editors. And it’s been great to be, hopefully, to be in a position as well where we’ve done the same for other people moving into or cutting across their career as well.

George Gendron: You say you travel 250 days a year. That has to have an impact on how much time you actually get to spend on an issue of Monocle. So is that true, number one? And if it is true, what are the things that you miss most about having more time to spend on Monocle?

Tyler Brûlé: So, first going back to the numbers game, obviously for this last period, it’s not been 250 days on the road. I do feel like I’m moving back to that. But yeah, you know, it’s interesting, if I think back before the start of the pandemic, I had shifted a little bit of my focus and my life to Zurich more than London.

I handed over the daily reins of the magazine to Andrew [Tuck]. Andrew became the editor-in-chief of the magazine, I took the title of editorial director. And that happened very naturally because, I think, on one side, we were just doing other things. There were so many other components.

And even though Andrew, of course, is across all of the content, things were becoming more complex in terms of the types of partnerships. I was playing a bit more of, I would say, the CEO role as well, looking after the brand in all of its aspects.

But who knows? We can revisit where I end up at the end of 2023, how much I’ve been traveling. But yes, I’m on the road a lot. And I don’t think it’s annoying for the rest of the team, but there’s one thing about going out there and knowing where we have either correspondents or we have bureaus, and arriving in a city and thinking and then I have to fire a note back to London saying, “Are we working on this story right now?” “Oh, no. No, we’re not working on it.” Or we might have passed on it—normally not passed on, they’re just not working on it. And I say, “How did we miss this? Why isn’t this commissioned already?”

And Andrew and I always have this conversation, in a really polite and forwarding way, about having done what we’ve done for a very long time that oftentimes other people just simply miss it. Of course we know the flip side of it all as well is if you’re in a market the whole time and your beat happens to be that Latin American city or that city in Southeast Asia, you just, you may not see it. But if you’re in Tokyo one day, then you’re in Taipei, then you’re in Singapore, then you’re in Bangkok and you’re like, “Oh, I was able to connect all of these things and isn’t it curious why this one thing is happening in Thailand at the moment.”

So I would say it actually helps inform what we’re doing. It allows Andrew and everyone back at base to get on with what they’re doing. And it allows me, probably, to be quite pointy and sharp and making sure that we’ve got the right stories going into the magazine and in a fashion which is, still, quite top-down you would say.

And of course that doesn’t inform everything we do. So I think it’s important. I think it’s a nice sparring match that I have between Andrew and the other editors. I’m sure it annoys them some days. Some days not. But I think it makes for a better product.

What do I miss? I miss the close of the magazine, because I’m normally not on the editorial floor in London. I have a set of walls here in Zurich, cork walls, where the issue does go up. But I’m able to look at the flat plan and look at the pace of the pages, et cetera.

But it’s not the same as the bar trolley being open on a Friday when you’re—or Tuesday is the hard close, I should say—Tuesday when you can flip through the book and you can open up a glass of wine, be with a team and celebrate that this has now been shipped off to Germany and it’s hitting the presses. That I miss.

George Gendron: That’s the best, isn’t it?

Tyler Brûlé: And that’s the power of the newsroom. And I think it’s the power of being together, and it’s the power of why we do what we do. And I think we were quite lucky—there were one or two issues that we weren’t all together properly, en masse, to get magazines out in that early spring of 2000 period. But, yeah, the good thing is we corrected that quite quickly. But that’s the magic of why we do what we do. And I think that’s the beauty of the editorial floor.

A natural spinoff has been a bespoke series of travel guides.

George Gendron: What, if anything, are you absolutely completely unwilling to delegate when it comes to the print edition of Monocle?

Tyler Brûlé: Well, I delegate many things, but I would never be in a situation where the cover goes without seeing it, without being able to look at the coverlines, without being able to contribute to the coverlines.

And, I don’t read every word anymore, but we’re in a situation where, if there’s something that Andrew thinks is critical that I need to see, I see it. But I have to see the entire issue. And when you see it pinned up on a wall, you’re not reading every word of the issue, of course.

But I can’t give that up. That is very important. And listen, it’s important to Andrew and Richard [Spencer Powell, Monocle’s creative director], and Josh [Fehnert, executive editor] and Sophie [Grove, editor of Konfekt] and all of the other people who are in the senior editorial mix that there’s also just a different set of eyes.

I mean, it’d be much worse if I didn’t make comments. But also if I didn’t see it, but then ranted about something because well, that’s down to me. Then why didn’t I see it? And, of course, we don’t catch everything and we have glitches and mistakes, like all media brands do. But that’s something, to me, which is essential and also makes me a journalist.

George Gendron: Listening to you talk, there is something—a kind of an authority and an aura—that comes with being a founder that you have to be aware of. People want your opinions. They want your input. They want your presence. Like it or not.

Tyler Brûlé: Yes. And that is, maybe, a little bit of the culture that also comes with being an independent publisher still, as well. We’re not part of a major conglomerate. And every success is our own. And every mistake is our own.

And there is also that sense of being an owner/founder that it is a high wire act every day. And there are no cables and nets. And no spotters on the ground, either. So it means that you really have to proceed with caution. But I think when you have the chance to do it, that you can also move forward at pace as well and with confidence.

In 2020, Brûlé and team launched Konfekt, “a deep dive into the worlds of fashion, craft, travel and design.”

“We’re not part of a major conglomerate. And every success is our own. And every mistake is our own.”

George Gendron: I want to talk about two things—one could be an entire podcast in its own right—and that is Monocle has a really interesting and I think, really healthy effect on a reader in the US which is that it’s interesting to pick up a publication or engage with a brand that is so non-US-centric.

Tyler Brûlé: So yeah. Discuss. Yes, discuss this topic. It is. And listen, it’s why the US is our biggest market, as well. Not just because it’s the biggest English-language market in the world. I think we could maybe sell more copies in the UK alone. And the UK is very close, but the US is our biggest market. Newsstand subscriptions. Radio listeners. People buying products from us.

And I think part of it is because it’s an oasis of a different dialogue. It’s a different conversation, it’s a different lens. Of course we do cover the US. But again, we’ve always done so on our own terms. And it’s been really interesting to read and engage with some of the correspondence over the past few years as things have become more divisive in the United States.

Andrew and I say we’ve always done a good issue if we’re able to annoy both Democrats and Republicans with one issue. And one thing we do talk about—and maybe it was when you were just reading out some of the values and the mission statement that we had cooked up back in 2007—I don’t think we were talking about being a voice of reason then, but I think we, again, it’s not written, it’s not in any brand book, but we want to be pragmatic, and we want to be measured, and we want to be a place of common sense, as well. And I think, obviously, that is something which we're constantly pointing out. That we need to have a real commonsensical approach to things.

And it’s funny how that’s what—even without us talking about it—that’s what we get from our listeners and our readers as well. People say, “Oh, I just thank goodness you just speak some basic truth,” which might be right of center, it might be left of center, but we’re not setting out to have any political agenda around it. We just want to be pragmatic.

George Gendron: When I think about Monocle, print in particular, but I think it’s true of the brand in general. In fact, it is true of the brand in general. It’s certainly true of radio. I think that you guys really revel in creativity, innovation, invention, resourcefulness, imagination. You really revel in it. I don’t know what other word to use. And that leads to an interesting question which—this is going to sound like a non sequitur, but it’s not—is New York City over?

Tyler Brûlé: I don’t think it’s ever been our position. And this comes back to, and I don’t want to revel in a house view, but Monocle’s a place about the positive. We come from, I would say, a position of looking forward. That doesn’t mean that you ignore atrocities, bad behavior, missteps of the past, but there is also a component of what we do, which is let’s be solution driven.

So has New York stumbled? Is New York the place it was five years ago, 10 years ago, over 20 years ago, when it was the editorial hub of the world? No, I don’t think it is that place anymore. But it doesn’t mean it’s out. Because listen, I mean, still some of the world’s most important broadcasts and newspapers are coming out of that city.

But are they the broadcast or journalistic benchmarks that they once were? No. I think you look at a number of titles or outlets or bulletins which don’t have the same level of clout. Now, of course, the media landscape is much broader and of course it’s much more dispersed. So people have more options. But I would also say at the same time, some of those flagship brands are not quite what they were either. So some of it is on their own watch. It’s not just because of what’s happened with competition, attention deficit, and everything else.

George Gendron: I’m also thinking though, and I don’t mean to turn it into an anti-New York City screed. I grew up there. I love the city, but a lot of creatives have left, and they’ve left simply because it’s not affordable. And that’s an issue, certainly in the US, for cities like Boston, New York, San Francisco, to a lesser extent, LA. I guess I’m also asking this question about, kind of, affordability and creatives.

Tyler Brûlé: And that you need to have an affordable environment to be able to cut your teeth as an art director, as a photo editor? Yeah, in part. But London was never cheap. And I think back to the magazines, the titles which were really so important to me growing up. Hamburg was never a cheap city. And it continues to be one of the most expensive cities in the EU.

But I think back to the glory days—and the Hamburg period is probably the same—late eighties, nineties maybe even up into the early two thousands, it was never inexpensive. So I don’t fully buy that a city needs to be completely affordable. I think, as a young journalist, you need to be in the best environment and you need to be learning from the best.

And yeah, you might be able to do part of it. But I go back to Peter Jennings’s comments, like, don’t think you have to be part of the farm team to make your way back to Toronto, to make your way to New York. Just get out in the world. And in that case, I left Canada, went to the other side of the Atlantic, and still am largely over here.

Monocle has opened branded cafés and shops around the world, including Hong Kong, Tokyo, Toronto, Merano (Italy), as well as London and Zurich, pictured here.

George Gendron: So if a young, recent college grad, who is interested in a creative field, not just journalism, but it could be design, anything that we would think of as a creative endeavor and they said to you, if you were me, where would you go right now?

Tyler Brûlé: First I would say, don't, as a 24 year old, say to yourself—or certainly say to a potential employer—that you “only want to work from home” or you “only want flexi-working.” This I don’t understand because you have to be around people. And if you really want to be a journalist and—listen, if you want to go out and chance it as a writer, great. Go for it. Go out in the world.

But if you actually want to be part of the editorial process—whether that’s making a radio documentary, or turning out a great magazine weekly, or a newspaper supplement on the weekends, whatever it is—you have to be surrounded by people, be in a great environment. The serendipity that comes with it, the camaraderie that comes with it.

But if you’re talking about someone who’s 23, 24, the learning, the mentorship—that’s the first thing. And then I would say why go for second best? If you were in a town or a city which has a newspaper or monthly magazine, which is on its last legs, probably not the place that you want to start.

So, yeah, you might have to make a few lifestyle curbs if you go to New York, or you move to London, or you find yourself in Singapore, wherever those titles happen to be. I think you want to learn from the best.

George Gendron: That’s great advice. To wrap this up, I have to come back to something that, having led the Inc. magazine creative team for 20 years, just fascinates me about this conversation, and that is your reference to Monocle as a family business. Can you say more about that? You don’t have a family. It’s not as if you’ve got five kids and you’re thinking about, “Which of my five”—you know, an episode of Succession—“which of my kids is going to take over?” Tell me what you mean when you say Monocle is really a family business.

Tyler Brûlé: I would say we’re a family business in almost the traditional—not quite mom and pop sense—but that it’s family money. But I should also be very clear that I’m not from a wealthy background. There are no silver spoons. A lot of this was self-financed. But nevertheless, of course, there was help from my mom along the way. And my mom holds a board position in the very small Canadian part of the business. And when we talk about blood that is one part of it.

But it’s a family in the sense that a lot of us have been together for a long time. And I think about Jackie Deacon [Monocle’s production director] or Richard Spencer Powell—Jackie is the master of understanding printing presses and paper tonnage. And talk about a skill and an understanding of something which is just … it’s golden what she does. We go back to the mid-nineties as colleagues. Same with Richard Spencer Powell, our creative director. So, listen, there’s many contemporary ways of defining a family, but I would say that this is one of the more older-school ways to define it.

And then I say it’s a family business because it’s also the other people who are invested. I mean, we hold, we, me, hold 70% of the company. The other 30% are families. So there’s no private equity. Two percent of our shares are held by Nikkei. But again, Nikkei is a private company as well. But everyone else—they’re family offices from Texas, from Thailand, from elsewhere in Switzerland, from Sweden.

So these are also other individuals who love media, they're passionate about what we do. And a lot of it has to do with quality. So when I talk in terms of a family, that is what it is. And there are no kids that are going to take over the business—at least none that I’ve spawned. But who knows? But who knows what happens with some of the other family members who are in the business. And what do we do with this moving forward?

George Gendron: Do members of your team, like Richard, do they have equity?

Tyler Brûlé: No. As we’ve built and brought in other investors we’ve done the best we can to cut people in, in terms of bonuses and done the best to do right by them. But no, it’s held by the other families and our shareholders.

George Gendron: I hate to end on a negative note, but I have to ask: What happens, in terms of succession, if you get hit by a tram today?

Tyler Brûlé: And it’s very easy to get hit by a tram in Zurich. I always say they’re the silent killers. Listen, there’s a very talented team in place. It’s a little bit like the same question, people say, “Oh, you know, what was going to happen to Wallpaper* when you left?” Well, Wallpaper*’s still around and seemingly doing okay.

I think that’s the essence of a great brand, right? Magazines have written codes, and fonts, and grids, and a photographic style that needs to be maintained. And, of course, it has a team of people that knows how to uphold all of those things. It has editors who understand the types of stories that are going to be commissioned.

So I think we’ve put a very good framework in place. We did that in the last magazine we did. We’ve done that for lots of other clients—titles that you may not even know that we’ve worked on. And we continue to do it day in and day out with Monocle. So I think the title would do just fine.

Midori House, Monocle’s headquarters, is located in London’s chic Marylebone neighborhood, between Hyde Park and Regent’s Park.

For more information, visit Monocle.com, where, if you’re a subscriber, you can read articles, watch films, listen to radio, and buy all kinds of cool stuff.

MORE LIKE THIS…