A Freaking National Treasure

A conversation with illustrator Anita Kunz (The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, Time, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY COMMERCIAL TYPE

By any measure, Anita Kunz has built a dream career.

She’s won every award, been inducted into every hall of fame, won every medal and national distinction. When her native Canada ran out of honors to bestow, the country minted a postage stamp in her honor.

Over the last 40 years, the Toronto-based illustrator has created covers for The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, Time, and many (many!) others. On top of that, she’s now authored two volumes of her own work.

“She is,” as Gail Anderson, her former Rolling Stone collaborator puts it, “a freaking national treasure.”

And yet, despite all that success, Kunz confesses to still battling with self-doubt. No matter how great the genius or how many accolades hang on the wall, the familiar feeling of insecurity and inadequacy spares no one it seems. Is this good enough? Am I good enough? Every thinking creative person faces these questions at some point in their career.

While the universality of self-doubt may serve as consolation for those wrestling with some type of creative crisis, today’s guest has a different attitude about it. Instead of trying to quash self-doubt, “embrace it,” she says.

“Self doubt is fuel—a generative force. Allowing a measure of uncertainty fosters experimentation, playfulness, and an open-mindedness that helps keep the ego in check.” And in a profession like editorial illustration, where rejection is ever present, self-doubt can transform into a survival skill.

In this episode, we delve into all of this, and we’ll talk about Kunz’ recent turn as an author, her favorite art directors, and that time she collaborated with an artistic monkey named “Pockets Warhol.” We also go into a dark moment when she was embroiled in a nightmarish copyright lawsuit. And, because it’s 2023, we’ll talk about what artificial intelligence means for her profession.

Anne Quito: Anita, I’m so pleased to finally be here. Since we first spoke I’ve watched, listened, talked to some of your colleagues. So I was thinking we’d start from the beginning. When we first corresponded, we chuckled at the notion that we share kind of the same name.

Anita Kunz: That’s right.

Anne Quito: And then you said that your ancestors trace back to Transylvania. Can you talk a little bit about your background and your family?

Anita Kunz: Well, sure. Yeah, so we are from a long line of people from Transylvania. In the 12th century there was a group of German people who went and settled in Transylvania, which, you know, is Romania.

And so I think what happened was that they, at that time, I mean this is so long ago, but I think at that time they needed to settle Romania, and I think a lot of Germans went and made their homes there. They were farmers and peasants and I think they were given a pretty good deal. I think they were given land and they didn’t have to pay taxes for five years.

And I just recently have been doing a bit more research into it and I find it really fascinating. We went there a few years ago and it’s beautiful and rugged and the, you know, the mountains are just, it’s just beautiful.

People think it’s very weird, and I remember my mother didn’t really talk about it that much because she didn’t like the way people talked about her people. She didn’t like the whole vampire thing, right? But anyway, if anybody is interested in Transylvania, King Charles has an Airbnb there and you can go, and one of these things that I discovered is that he is a very distant cousin to Vlad the Impaler. So there is a Transylvania connection. But that’s the extent of what I know.

Anne Quito: That’s incredible. So good. And your last name—I always have this hunch—I mean, I’m a reporter and I meet a lot of people and sometimes someone’s last name, or I would say often, gives a clue about their ilk. And your last name is Kunz, German for “art.” As if you are destined for this profession.

Anita Kunz: I guess so. I guess so. It’s very, very close. It’s “kunst,” but, yeah it’s, it’s very close.

Kunz’ uncle Robert Kunz (above)—a major influence for her—was an illustrator in Toronto.

Anne Quito: Yeah. Was art a big part of your upbringing? I know you were influenced by your uncle. Maybe you can talk a little bit about that.

Anita Kunz: Yeah. My first, and one of my biggest, influences ever was my uncle Robert Kunz. And he was an illustrator. And this was way back, way back when, and his motto was “Art for Education.”

And so, kind of from that, I learned that it would be great if art could serve some kind of a purpose or be useful in some way. And it didn’t just need to be decorative, it could perform a function. And he was a huge inspiration. Not only was he an illustrator, he illustrated all the textbooks when we were in high school and he did the “Children’s Corner” in our local paper in Toronto. He was just amazing.

But also, he was just a quintessential artist. He did weavings, and he made architectural freezes, and landscapes, and all that kind of stuff. But what I loved about him is that he also influenced me on my worldview, which is that he had a studio on the lake. He was an environmentalist, and he knew the names of all the animals. So I loved that whole, that aspect, of him too. So, yeah, the first big influence for sure.

Anne Quito: I’m going to make a sharp turn to magazines. Because when you spoke, you said you’ve always loved magazines and this is what you wanted to do. Can you talk a little bit about why? I know you did some early work in advertising as well, but what made you fall in love with magazines?

Anita Kunz: Well, you know, I didn’t know what I was going to do. When I went to art school, I went to the Ontario College of Art, and the only thing that I knew was that I wanted to draw pictures and I needed to make a living. It was as simple as that.

So I went to college and I thought, well, I guess I’ll be a children’s book illustrator. And then I developed this kind of very cute style. And then I did some advertising. But actually, I did quite a bit of advertising and I was able to, you know, I was lucky to make some money, but I got tired of drawing little animals in skirts and making cute stuff.

And I wanted to grow and I wanted to do things that were really interesting to me and things that were more political. And anyway…

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards as Fred Flintstone and Barney Rubble for Rolling Stone.

Anne Quito: I heard you describe your very first paintings as “very, very dark.” Is that true?

Anita Kunz: Okay, so I went through a phase where I did really cute stuff. But then what happened was, I became very influenced by some of the British artists. And what happened at that time, and this really catapulted me into magazine work, was that two great art directors came to Toronto through Toronto to New York via the UK. And it was Robert Priest and Derek Ungless.

A Ralph Steadman portrait of Kunz.

And they went on to do great things in the magazine field. But what they did in Toronto was Weekend Magazine. And Weekend Magazine came out once a week and it was kind of a general interest magazine, but they were using people like Sue Coe for skiing, for a skiing article. They did a great cover of the Anti-Fur Industry by Ralph Steadman. And I just began to really love the work of the British illustrators.

And the work was darker. And I really tried to stretch instead of doing, you know, work that was cute and “palatable,” I just really wanted to get into doing some more substantial work and to really be more of an artist and make work that was much more personal. So that’s kind of where that’s where that started.

But also, when I started, there seemed to have been so many possibilities. I mean, these art directors were doing really amazing creative work. It was really out of the box thinking. I’ve been thinking, I knew I was going to talk to you about this. I’ve been trying to think of examples. I’m pretty sure it was Robert Priest, who was doing something for a magazine. It was a fiction piece, and it was about three very different characters. So he got three different illustrators to illustrate one piece. This is really amazing thinking.

So very, very early on I was drawn a little bit to dark work. But also I just loved, to me there seemed like endless possibilities in the magazine field.

Anne Quito: I hear some nostalgia for what was. Why do you think things changed so abruptly? Do you think it’s the speed of production? What happened?

Anita Kunz: We’re talking about a span of 40 years here. I don’t know how they got away with it, except that they were allowed to do really creative work by the publishers. By the editors. So I think it all goes up to who’s running the show.

But I do remember back then, doing all of this social- and politically-oriented work and having carte blanche, like having complete autonomy. That’s the kind of thing that I think is really different now. I would get a manuscript and I would be asked to give maybe one or two sketches. But I think back then there were a lot more art directors who were thinking in terms of, not style necessarily, just style, but that the illustrators, maybe, we had a brain and that we had thoughts about these things, and we had emotional reactions, and we had intellectual reactions to the piece, and then it didn’t just have to be the way it looked.

“Very early on I was drawn to dark work. But there seemed like endless possibilities in the magazine field.”

Kunz’ 2017 cover for Variety was a nod to a 1968 Esquire cover featuring Richard Nixon.

Anne Quito: Do you remember your first magazine cover?

Anita Kunz: The first cover…I’ll tell you the first illustration I ever did. The first public illustration I ever did, I got out of school and, you do everything that you’re going to do and, you spend hours putting together a portfolio and it has to be perfect. And you’ve asked all your teachers what you need to do. And, so I went out there and I got a—it was for Toronto Calendar magazine or something. It was about the “Great Canadian Bathtub Race.” And it was something so inconsequential. And I think it was maybe a three-inch wide spot.

And it was just really silly. It was just probably some little, I don’t even remember, some little race to do with charity. And I got the job on Friday, and I immediately went into an anxiety attack/panic mode. I cried all weekend. I delivered the job. I’m like, it’s so cute when I think about it now. I was just so desperate that this was going to be this incredible piece for the Great Canadian Bathtub Race.

It was just, it’s kinda sweet when I think about it now, but I guess they liked it. I must have chilled out a little bit after that, but I thought, “I can’t do this. This is so stressful. I can’t do this.”

Anne Quito: I want to go back to that emotional rollercoaster, but first I’ve got to ask, what is the Great Canadian Bathtub Race?

Anita Kunz: I can’t really remember. Well, I don’t remember what it was, but I think it was just a silly thing. I assume it was done for charity. But I mean, that was my big splash into the field of illustration.

Anne Quito: I want to go back to what you said about art directors and freedom. And your work has been, as we all know, has been published in every major magazine over the four decades: Time, Newsweek, GQ, The New York Times, The New Yorker. Can you tell me what makes a good art director?

Anita Kunz: I actually have an awful lot to say about that because without great art directors illustration really can’t thrive. The ones who are the most open-minded and interested are the ones that, you know and, in my view, offer the most creative freedom, I think are the best. And I am so endlessly lucky that I’ve gotten to work with these incredible people. I’ll name some of them if you don’t mind.

In Toronto one of the first great art directors I worked for was Louis Fishauf. And he was at Saturday Night magazine. And this was after my cute phase. This is when I was doing serious illustration. But the subjects that he gave me to illustrate, I mean, I remember there was one about Helmut Rauka, who was a Nazi war criminal found living in Toronto, and the assignment was to basically read it and come up with a couple ideas and that was it. It’s a far cry from what happens now where it seems like almost every detail we’re being told exactly what to draw. But, I had such a visceral reaction to the story. I think that always helps come up with a better image.

I’m just going to interject here and say, I moved to England for a while and I went to see the art directors there. And I went to see Gary Day-Ellison at Picador Books, I knew he was a great art director, and the first thing he asked me was, “What do you read?” I mean, that sounds like such a nothing question, but it was so that he could know what kind of jobs that I could do my best at.

I worked for Steve Heller. I worked—I was in the right place at the right time. Tremendous luck. Arthur Hochstein. I got to do Time covers. And I did some Canadian Time covers for Edel [Rodriguez]. But, I didn’t want to make a list for you because I knew that if I left some people out, I would feel terrible for a week after. But just all this wonderful work that we illustrators used to get, you know?

I used to get two or three jobs a week and I just wrote down some of the topics all over the place, but really interesting. Socially- and politically-oriented subject matter about things like marijuana legislation, chronic fatigue syndrome, Viagra—I did a Time cover about Viagra—American politics, motherhood. I did the sex column for GQ. Censorship, the drug wars, gun control, child abuse, politics. This was pretty heavy stuff.

And a lot of us illustrators because we were given this great, tremendous freedom, I really think it was a little golden age in the eighties and nineties. I didn’t realize how great it was and how lucky I was to have that kind of freedom to make pictures and have everybody see them. It was amazing.

Anne Quito: I love hearing those stories, but as we know with great freedom, the burden goes to the illustrator to come up with a novel, original solution. Now, I spoke to one of your former art directors at Rolling Stone, Gail Anderson. I said to her, “What would you ask Anita if you could ask her anything?” Actually, her real answer is, “Can I buy one of her paintings?”

Anita Kunz: Oh, but I’ll send her one. Oh my goodness.

A 1987 Rolling Stone cover portrait of Michael Jackson

Anne Quito: But her real question is—I’ll read it—she says, “How has she kept it going at such a high level for so many years?” She says, “I mean, I go back to 1994 with Anita, and that was a long time ago. Anita’s managed to get better and better and has never rested on her multiple laurels.” How do you keep it going? How do you keep it fresh?

Anita Kunz: Well, that’s, that’s incredibly sweet. I think Gail is one of the great art directors. I loved working for her. First of all, I could talk for an hour about Fred Woodward. Maybe we can talk about him. But just working for Gail. You know, she was—she is—one of the greats, and I don’t think a lot of people realized at the time that Fred was doing all these amazing spreads and designing all this great stuff, but so was Gail.

I think a lot of people may have assumed that it was all Fred, but she has always done this, like, amazingly terrific stuff. And I certainly was hoping that she would get the art direction job after Fred left, but you know, she’s absolutely amazing.

But I could ask her the same thing. How does she keep it going? But I think I just have a restlessness. There’s all kinds of stuff I still need to do, feel like I want to do. As I get older, I feel more of a sense of urgency, like, “Oh, I want to do this,” and, you know, “I need to do a book about this.” So there’s all this stuff I still want to do.

Also, I’m absolutely terrible at boredom. Some dark things happen when I’m bored. I really need to keep—I need to keep busy. The pandemic was, you know… I don’t know. I had to do something, so I painted 400 pictures of women to know.

Anne Quito: That’s incredible!

Anita Kunz: But I got stuff done. I just am very restless as a person and I just need to keep doing stuff. So that’s the real answer. But thank you Gail.

Anne Quito: I’m going to go back to the book and the 400 portraits in a second. But I want to ask you—so you are restless, you are thinking of ideas. What happens if you ever get stuck? I always ask this because, as a writer, there are some things like “walk around the block,” “drink a lot of water.” I don’t know, some weird tactics. But it’s never worked for me. My only thing is to start. I wonder if you’ve ever experienced the so-called block on a deadline?

Anita Kunz: Yeah. Oh, sure. Yeah. I don’t think there are any artists or writers who don’t. But I think sometimes I remember in the past I just got really tired of doing the same thing and using the same formula. And I just thought, “That’s it.” And I got some clay and I started playing with clay and I just needed to pound out some of the frustration.

But I think I try something different. I think that’s the answer. Just I try something different. But it happens a lot and I think whatever you can do I think everything that you said is right, go for a walk.

But I’ve put together all these quotes for students and I can’t remember who it was. It may have been Chuck Close, maybe it was Milton, it was probably Milton Glaser, who said, “You just have to sit down and keep going and it’ll come back.” You know, it’s not always about inspiration. It’s about just sitting down and actually getting the work done and it will come back. And I’ve found that there are always ups and downs, but it will come back. Or maybe it won’t. I don’t know. It hasn’t—I’m still doing it. I don’t know.

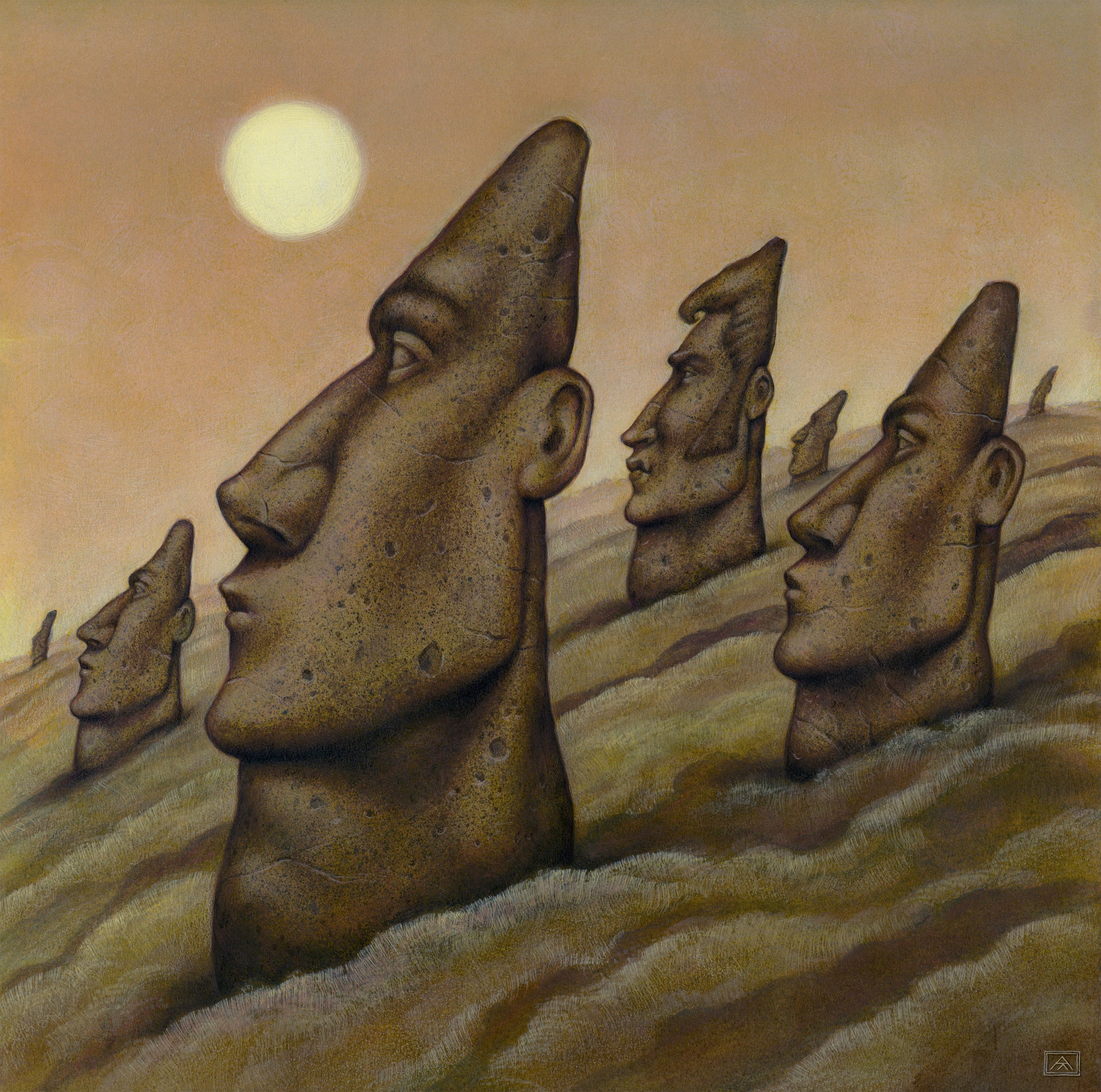

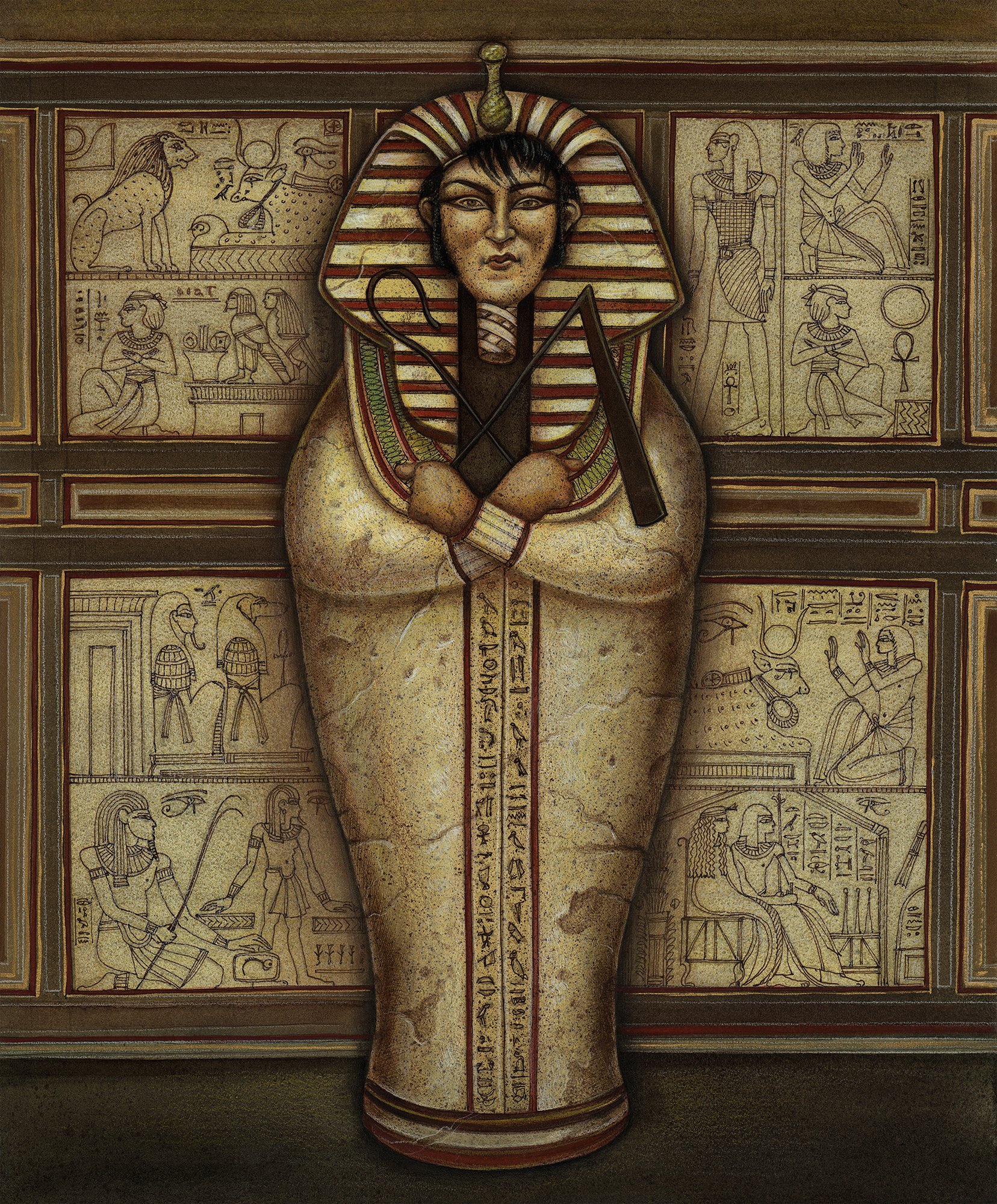

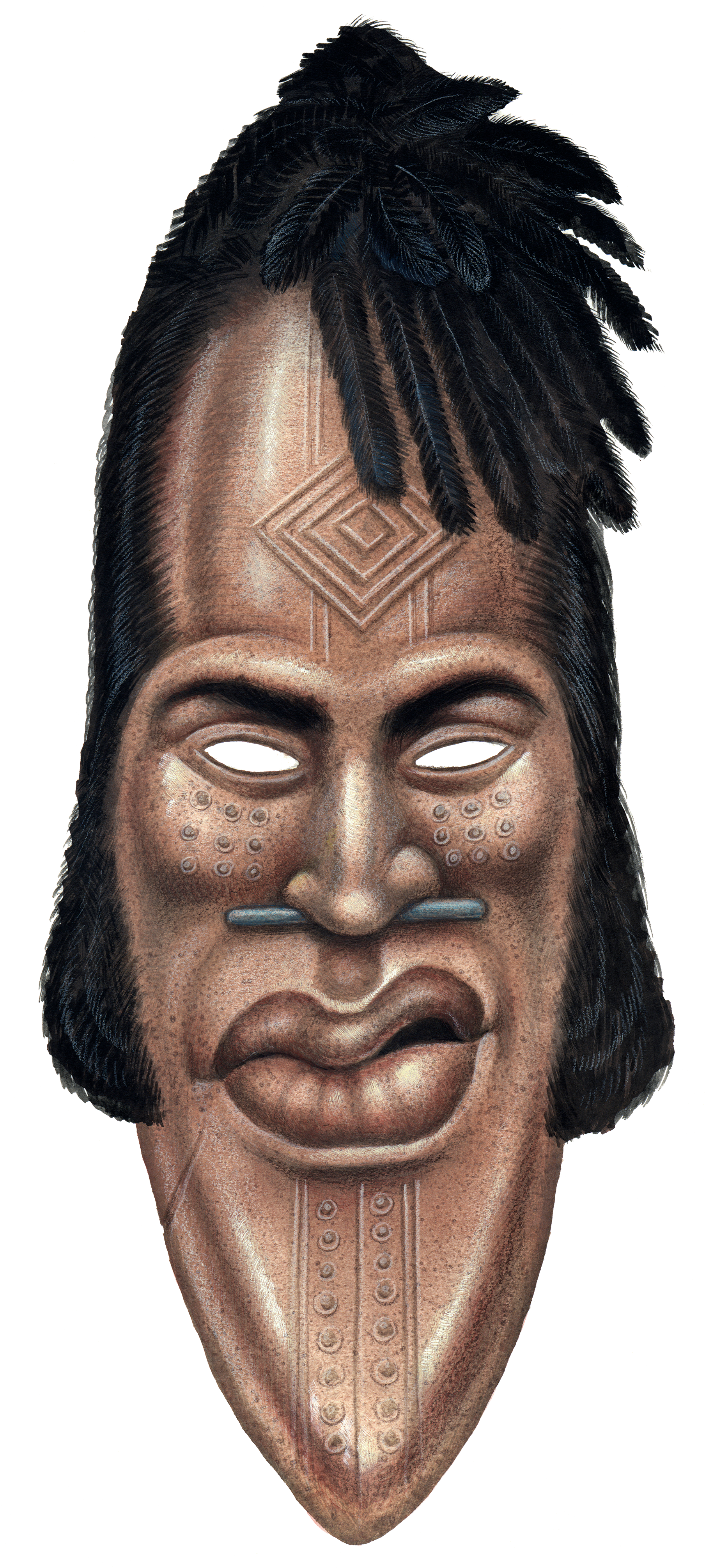

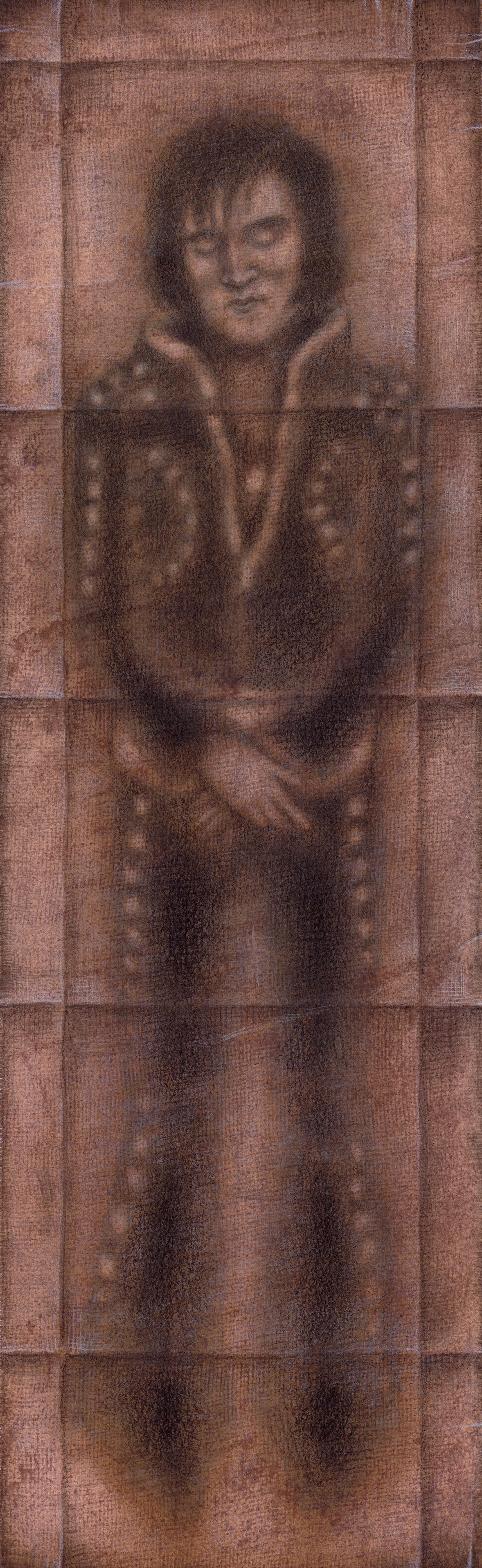

For a 1989 Rolling Stone feature titled “In Search of Historic Elvis,” Kunz portrayed the King throughout history.

Anne Quito: You’re still doing it. You’re living proof that it works. You’ve also talked a lot about handling rejection. Now in those 10 tips you give to creatives you’ve written, I think, a list that you constantly update maybe. But one of them I was really struck by. You said, “Embrace self-doubt. It will propel you forward.” Now I have a follow-up question there. Self-doubt can sometimes be interpreted as a lack of confidence. It can be a negative. But how do you spin that? How do you propel that forward? And also where does the artist’s ego or voice come into this interplay?

Anita Kunz: First of all, rejection is so commonplace in the arts. You really have to develop a thick skin. So I don’t really quite know how I did it, but the whole thing about moving through the gut churn or whatever. Milton Glaser said that. So what I’ve written for students is really stuff that I never knew. I was wondering why, when I was young, like, “What’s wrong with me? Why am I always dissatisfied?” And, you know, “What can I do?” And, “What can I do to be better?” And, “What’s wrong with me?”

I always used to think that kind of stuff, but I never learned anything in school about that. What we learned in school was that, “Here’s how you do the job and here’s what you do. But none of the surrounding things. So yeah, it’s just moving through it, and I think the bottom line is just, it’s something that you feel that you need to do. And so whatever it takes, it just needs to be done.

And I don’t know where I developed that kind of tenacity. I think I was just always really stubborn. And I still have a lot of rejection. It’s really common. And I think it’s important for students to know that. It’s not them.

Anne Quito: I wanted to probe more on the self-doubt thing. I wonder how you feel whenever you submit an illustration. What are the feelings swirling around you? You talked about how you felt for the first illustration, you were wrecked with doubt and worry. Has that simmered down? How do you feel?

Anita Kunz: Thankfully it simmered down, otherwise I would’ve had to do something else. But when I do commercial illustration, every one is really different. Every job has its own set of parameters. Sometimes they’re completely self-generated. But for the most part, when I hand them in, there’s no great eureka! There’s no great joy. I always think I could have done better. And when I see it in print, I think, “Ah, I should’ve done this, or I shouldn’t have done that.”

I listened to Barry Blitt’s episode—which was great, by the way—and I was actually interested to hear that he does things two and three times. So for somebody like him, I mean, part of what he does that’s so brilliant is that the work looks so effortless.

But anyway, I don’t really know too many artists who aren’t insecure or don’t have tremendous self-doubt. I think that’s kind of the nature of the beast.

“It was a golden age in the eighties and nineties. I didn’t realize how lucky I was to have that kind of freedom to make pictures. It was amazing. ”

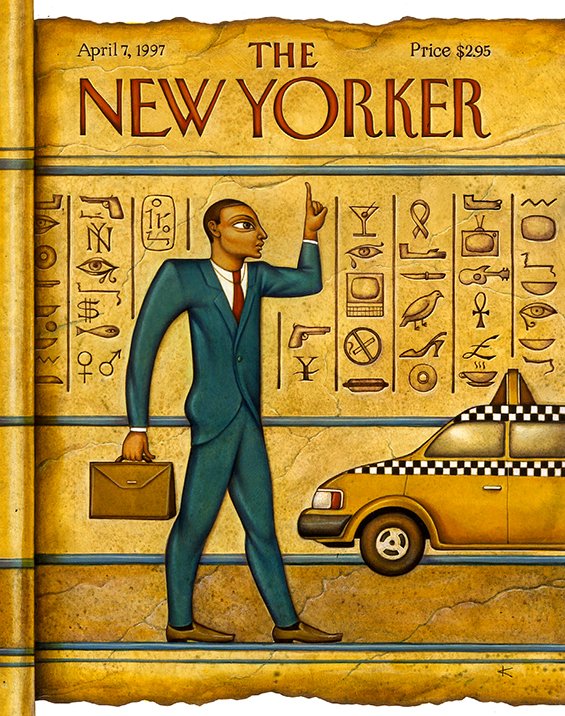

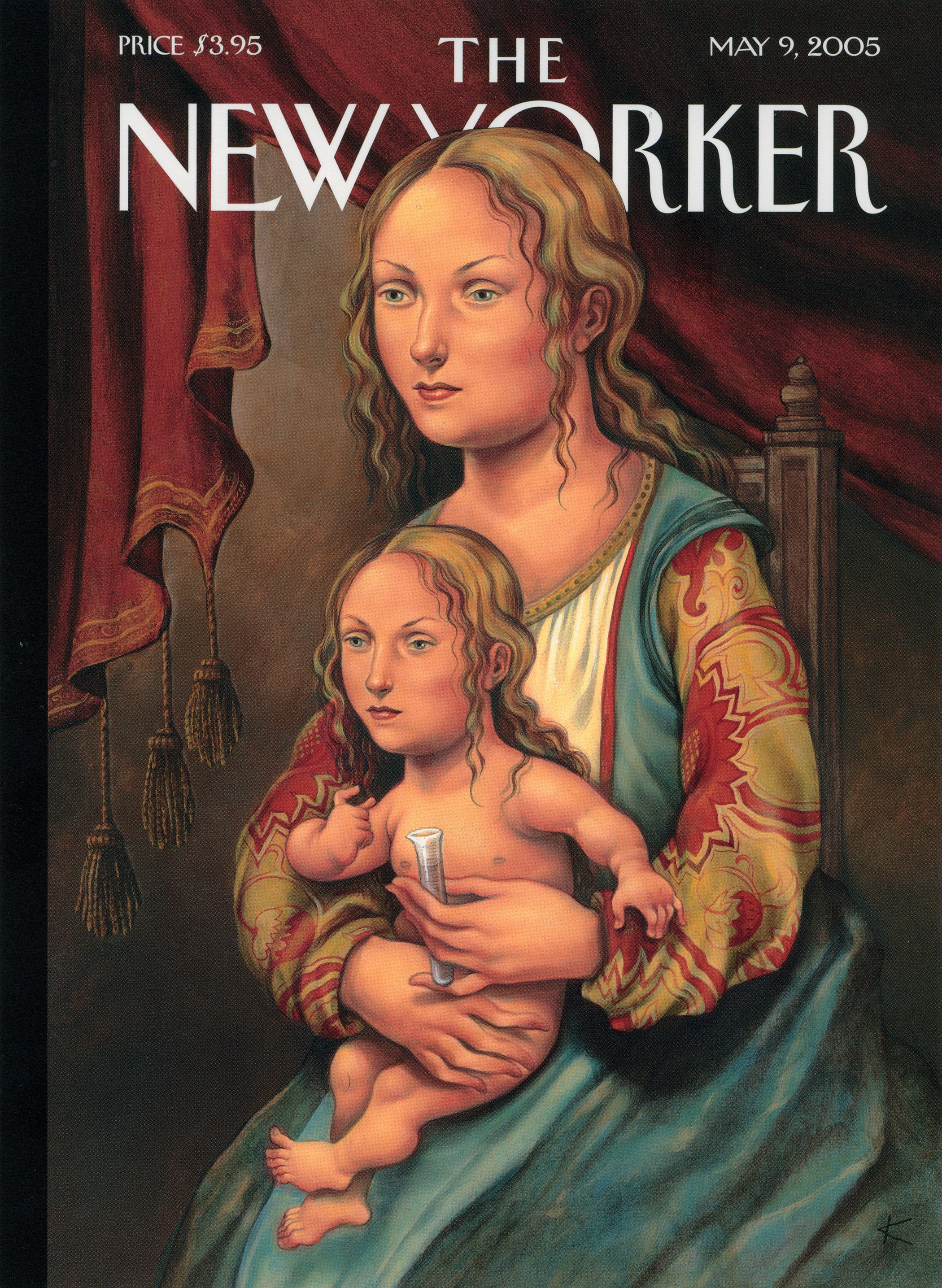

“The New Yorker was 100% behind me,” says Kunz after another artist claimed Mohawk Manhattan (above) was a stolen idea.

Anne Quito: Can I ask you about what you described as maybe the darkest point in your career? Is that okay? I read about a lawsuit you were embroiled in—sorry to bring that up—with The New Yorker. I think it was a 1995 cover, and someone claimed that he had the same idea. But what really interested me was you saying that after that, you became a little paranoid?

Anita Kunz: Well, I was paranoid to begin with, but that didn’t help. Well, there was an artist who—after my first New Yorker cover, it was 1995, and I was so thrilled. And, first of all, Françoise [Mouly] is another person we could talk about for an hour. She’s amazing.

But yeah, so I did my first cover and it was called “Mohawk Manhattan,” and it was around the July 4th weekend, and it was all about, “America! Rah, rah, rah!” But I wanted to sort of do something about, you know, Native Americans, and that they were really the ones who were ripped off.

So I wanted to make a nod to Native Americans. You know, let’s think about that on July 4th. So I did “Mohawk Manhattan,” and it was an indigenous person with a Manhattan skyline. And so after, I was thrilled. My first job. I was so happy.

And Françoise called me and said, “There’s somebody here who said you stole his idea.” And I said, “Oh, okay. Who is it?” And she gave me information and I called him. And probably I shouldn’t—like now, that would never happen. Now, it would just be like, “Let’s get the lawyer.”

So anyway, he seemed to think that I stole this idea. I didn’t know who he was. Nobody I knew knew who he was. And he presented me with a lawsuit. It took four years in Manhattan civil court. It was kind of a nightmare. And the whole point was that it was a plagiarism lawsuit. He said I stole his idea.

But of course the further we went along, the more ridiculous it sounded. Really ridiculous. And then ultimately, of course, we won. But what ended up happening was now, if you become a copyright lawyer—it’s a precedent setting case.

Nobody has ever challenged the notion of copyright. So after all said and done, it’s something that young copyright lawyers learn about. So it’s a very famous case. But what you said is correct. I mean, when you’re accused of something like that you’re thinking, you know, “Maybe I was walking in New York and someone walked by with a t-shirt on and I subconsciously registered it.”

And so every time I did a job and the idea came too quickly, I remember thinking, “Oh, I must have seen it.” It really jeopardized my ability to come up with ideas. And of course, we know that ideas are not copyrightable. So it basically made that case. But yeah, that was a really low point for me.

But I have to say, The New Yorker was 100% behind me. Because if you’ve worked in this business long enough, you know that the ideas are something that we all use freely. I used to work for Newsweek and Time magazine, and sometimes they would come up with the same idea. That’s why we use ideas to, you know, to talk about concepts.

Kunz in her Toronto studio

Anne Quito: And also with social media, on Instagram. We’re saturated with images.

Anita Kunz: Yeah, absolutely.

Anne Quito: Have you gotten over this sort of paranoia or like double checking if someone has ever done the same construct?

Anita Kunz: Well, I think I understand that it happens. I remember my beloved—my great art teacher, Alan Cober, one time we came up with the same idea. It was for something about pollution. It was an Earth Day and we both did like a pig with, you know, and it was just, we laughed about it because that’s what happens.

But one of the things I do now deliberately is, before I submit something, maybe to The New Yorker, I’ll do a Google search and if it’s been done, I won’t do it. So I sort of preempt it just in case, but that’s fair enough. I don’t want to do something if someone else has done it anyway. It’s just courtesy.

Anne Quito: I want to shift to your techniques and tools. I know you told me that you still paint in this sort of era of digital illustration.

Anita Kunz: Yeah.

Anne Quito: You use acrylic paint and there’s a particular thing we had talked about. I said that I love how you render eyes and you said, “Oh, actually people have commented on how I render hands.”

Anita Kunz: Oh, that’s right.

Anne Quito: Can you talk about your hands, how you take care of them and why this fascination with hands?

Anita Kunz: I mean, it’s just the way I draw, honestly. When I started, I just tried to get it together to do a drawing quickly because there were always deadlines, and how to make something as expressive as possible. And I thought the use of hands always made something a little bit more, more expressive. I guess that’s the only word I can think of.

So that was something I think I probably overused early on, but when I started, the, the medium I’ve always worked in traditional media. Right now it’s acrylic. When I first started it was watercolor. But when I was working for magazines, everything had to be done so quickly.

So I couldn’t make a giant painting and use oil paints, although some people do. I don’t know how they do it. But, for me it was, if I had a day to do something, I had to do it quickly, and I had a certain amount of real estate to fill. And so for me that meant working in water-based materials, which I’m glad I did because it’s green. It’s safe. That stuff is safe to use. There’s no turpentine or benzene or anything like that. It’s all green.

And I still used traditional—I mean, I’ve sort of grudgingly learned Photoshop just because it’s something I have to do. Of course there’s no sending via FedEx the final art anymore. I need to be professional and properly scan and color correct and all that stuff.

But still, I like painting and these days I’m working less to specifics and I’m doing a lot of my own stuff. And so I’m just experimenting with working really big and trying different materials, trying acrylic. Painting big forces you to change the nature of the way that you work. So I don’t work with little tiny watercolor brushes as much anymore like I used to.

Anne Quito: That’s wonderful. You mentioned Milton Glaser a couple times. I was with him till, you know, his last years working in his studio and working on a book, and his hands, to the last day, were perfect.

Anita Kunz: Really?

Anne Quito: No shaking. I think one time he experienced a little tremble and he said something about—is it Matisse?— leaning into how your hand shifts? And he did a portrait just sort of like deliberately with a shaky hand. But, he also said that “the brain is directly connected to the hand.” And it’s a weird statement. I have never stopped thinking about it. But whenever I see him, I look at his hands and they’re perfect.

Anita Kunz: That’s amazing. I was so in awe of him. I think the few times that I met him, I probably didn’t notice that much. But certainly I think he was absolutely one of the greats.

Anne Quito: I want to talk about your fascination with portraiture. You’ve done many, many portraits, but I particularly love your self portraits. I found one—you as Frida Kahlo. You as Albrecht Dürer. You as Mona Lisa. Can you talk a little bit about your approach to portraiture and why you chose some of these characters to embody you?

Anita Kunz: Yeah. When I think back, I really did start doing mostly socially- and politically-oriented work and using metaphor and, to illustrate these things. But I think when I started working with Fred Woodward—he’s the one that gave me my first portrait assignments.

And it was one of those things—I didn’t deliberately say, “Okay, I’m going to do portraits now.” But I think the first thing I ever did for him was Ray Charles, and it was for the Dallas Times Herald or something. [Ed: Woodward was briefly the art director at Westward, the newspaper’s Sunday magazine. He left to become the art director at Texas Monthly]. And from that point on, he just kept giving conceptual portrait assignments.

And I thought they were great. I mean, I loved doing them. I think I spent the majority of the years after doing almost predominantly portraits. But there was a lot of portrait work to be had—conceptual portraits. There was a lot of great stuff going on in the magazine world.

I was working for Time, Newsweek, The New York Times, Ms., Entertainment Weekly, Premiere. And they all wanted portraits because that’s what they were reporting on and what people, politicians, celebrities, were doing. So I shot off into the direction of doing almost entirely portraits, which I actually loved doing.

I wasn’t necessarily interested in, for Rolling Stone, doing some of the celebrities. I wasn’t as interested in painting the celebrities as I was why are they celebrities? That sort of was the backstory to that. But to your question I can’t remember why I did those three. I did three portraits of myself as my heroes, basically.

I think artists typically do self-portraits. Some artists do it more than others. And I always need portraits for things—you know, author’s photos—but I want to give them some art instead. It was just an homage to three of my favorite artists.

And I put myself as them, and I called them, “Three Portraits with Facial Hair.” It was just a silly thing. But it was kind of my faves.

Anne Quito: You mentioned heroes. If you could pick three of your, let’s say, heroes in illustration...

Anita Kunz: Oh, boy. Boy.

Anne Quito: ...who would it be?

Anita Kunz: Yeah, see now I’m going to feel bad because the second I stop talking to you I’m going to think of 10 others. But I would say that my favorites are always Ralph Steadman, Sue Coe, for just the incredible work that she does as an illustrator and also now is a fine artist. And I’m going to also at this point say Marshall Arisman. Because there’s no one who helped me more when I started. I was in Toronto for a while, moved to England for a while, and then came back to Canada wanting to work for the US market because the US market was huge.

So I gathered up my courage and I went to see Marshall Arisman. And he was so kind to me. And he gave me names of people to go see, and he really kind of jump started my career. He was extraordinary. And of course his work, you know, he was such a kind man just by himself, but the work was extraordinary.

Here was somebody who was thought of as an illustrator, but absolutely straddled that fence into fine art beautifully. And his work was beautiful, and moving, and touching. So those are three, but there are tons more. Lots more.

SNL alum John Belushi on a 2015 Rolling Stone cover

“I’m sounding like a real grouch, but I really don’t like collaborating.”

Anne Quito: What you said about Marshall Arisman is so true. I met him, and that is perfectly accurate. Kindness and genius bundled in one.

Anita Kunz: Absolutely.

Anne Quito: If you could commission any artist or illustrator, I don’t know, in history to paint your portrait, who might it be?

Anita Kunz: Yeah. I really, I don’t know. I don’t know. I mean, I’ve had my portrait done by a few people, but I think I’ve already had one done that I’m going to stick with. And it’s a picture that Ralph Steadman did of me riding a camel. And that’s hanging in my house. And if nobody else ever paints my portrait, I’ll be happy about that. I’ll be happy with that one.

But my favorite illustrators are ones who are incredible thinkers, who are concerned for humanity, who just go ahead and do what they feel like they’re meant to do. And they’re just incredible. But definitely at the top is Ralph.

Anne Quito: What a trip! Ralph over Leonardo da Vinci. Vermeer. Incredible.

Anita Kunz: Yeah, no, Vermeer would’ve been cool. I didn’t realize I could go back that far.

Anne Quito: I spoke to Mark Heflin, at American Illustration, and he has only loving words to say about you. I asked him a few questions, but he basically just sent me sort of this really loving, almost essay about how you’ve contributed to the illustration industry, not just about your work, but like how you’ve really been a voice for this industry. He gives three ingredients to describe your work: beauty, humor, and insight. Are those three things you try to balance?

Anita Kunz: That’s, that’s incredibly kind. I’m not quite sure what to say. That’s, that’s incredibly kind. I love Mark. I love what he’s doing. The American Illustration Annual, you know, right from the beginning—if you look at even the early annuals, you’ll see such an extraordinary array of illustration work. You know, everybody had a different style. Everybody was completely autonomous. It was really about their personal vision. It was much more like an art book than an illustration annual.

And the fact that he keeps doing it. And at that time, that was really a testament to the kind of autonomy that we all had. But anyway, I’m so grateful that he keeps this incredible book going. So he’s, yeah, he’s a dear friend.

“I love drawing monkeys,” says Kunz, who volunteered at a Canadian primate sanctuary during the pandemic.

Anne Quito: I love listening to your tirade against collaboration. I think I heard it in another—I love how you said, like, “You have to be given permission to realize your vision,” to be able to, like, I love this sort of assertiveness about “individual vision.” However … you’ve collaborated with a monkey.

Anita Kunz: Oh! I was wondering where this was going. Okay. I’m sounding like a real grouch, but I really don’t like collaborating. Because when I collaborate with somebody, I keep thinking what do they want and how do I please them instead of keeping it to what I think is best. But yes, I have collaborated with the monkey.

I’m glad it’s leading to this. So for about five years—I haven’t done anything recently, because Covid changed all of that—I was volunteering at a monkey sanctuary, the only primate sanctuary in Canada that rescues pet monkeys and monkeys who have spent their lives in labs, and they give them a good retirement.

So it was, for me, it was just really interesting because I love drawing monkeys anyway, and I just think they’re so human-like and I think we’re so monkey-like, and so just from that standpoint it was really amazing to sort of just be around monkeys. But one thing that they do that I think is really kind of interesting is that there’s a white-capped capuchin monkey that they named “Pockets Warhol” because he looked like Andy Warhol with his hair, and he really likes painting.

So there’s one person there who works with him and she puts out paint and he sits there and he makes these paintings. And it’s really good for one of the things that with captive animals you try to keep them busy and keep them happy and not just have them sit in cages. You try to keep them occupied. So that’s one thing that he likes to do. He just loves painting and the sanctuary sells them, and he really helps to keep it going.

But what I did once is I thought, “Well what, what would happen if I collaborated with him?” Just for fun, just to see what would happen. And so I gave a painting and he started working on it. Actually, we did this a few times now that I think about it. But the first one ever was a picture I did of a woman and a monkey, and he looked at it and he painted over it and I think he improved it. But then the very last thing he did was he put a slash over the woman’s head. And I thought, “Whoa, that’s a political comment right there, isn’t it?”

But that was just one of those fun things that you know it was just, it was really fun and hopefully helpful for the sanctuary.

Anne Quito: I love that. And you’ve done a portrait of Ellen DeGeneres together?

Anita Kunz: Yes, we did. Because Ellen is such an animal lover. Yeah. Oh, wait! We did a portrait of Ricky Gervais too!

Anne Quito: Oh my goodness!

Anita Kunz: Because Ricky Gervais is actually a supporter of the sanctuary, too.

Anne Quito: You mentioned volunteering at sanctuaries. I was wondering, it sounds like you might be working all the time and very busy with illustration work, steeped in this industry, in this profession. But do you have hobbies outside of illustration, or art, or your profession? What do you like to watch? What do you like to read? Any guilty pleasures we should know about?

Anita Kunz: Oh, of course Lots of guilty pleasures. I just finished watching Black Mirror—oh my goodness! Anyway, if you haven’t watched it yet, the first one is about AI. But as far as anything else, I am not a polymath. I’m terrible at everything else. The only thing I can do is illustrate, seemingly. So thank goodness I was able to be so lucky as to have found so many great art directors to work with.

But yeah, I’m not very good at other things. I’m a terrible cook. I really don’t, you know, I’m not much good at anything else. But I have to say, going back to my uncle, I love being in nature. I love spending time in nature. I love kayaking and being out in the winter. So I’m a big nature lover and a big you know, animal advocate. You know, I do as much as I can, but I’m not working all the time, especially now.

I spend tons of time working on a project and now I feel like I’m a little bit between projects, but there’s always stuff to do. Like, you know, I need to organize my last project and it’s going to be a traveling show. So there’s all kinds of stuff that needs to be done for that. So there’s always, there’s always stuff to do.

Anne Quito: I also heard that you might be an incredible snowboarder.

Anita Kunz: Oh, well, I was certainly one of the first, but I haven’t done it recently. My bones are getting a bit creaky for that, but I used to love it. Yeah, I used to love it. We were the young punks on the hill, but that was many, many years ago.

Anne Quito: I want to switch to your books. The 400 portraits and the books that you’ve mentioned. So from doing a lot of commissions and working for magazines, you’ve, I guess during the pandemic, began, these two and three—actually there’s a third one coming—you began these projects for yourself. Can you talk a little about, first about Another History of Art, which I love?

Anita Kunz: Well, thank you. Years ago, I think maybe 20 years ago, I started doing my own work. I wasn’t getting the kind of freedom that I liked anymore in the publishing world, and I just started trying other things. I started trying to paint really big. I actually tried an excursion into the art world, which failed miserably. I mean, illustration does not translate well into the art world, I have found. There’s some kind of a stigma. If you’ve been an illustrator, watch out.

But I had these paintings and I thought, even as I moved away from print, I always come back to print, and I think it’s interesting that this whole podcast is about, is print dead, because I always seem to come back to it.

So I made a whole bunch of paintings and the art world, somehow, I didn’t have the right pedigree or I don’t know what that was about, but, I thought, “Well, I think this might be a book.” So Another History of Art became a book. And it’s satirical—I think my work is satirical, but it always has kind of a dark undertone.

So really, it’s meant to be funny and it takes a look at the history of art and how there are hardly any women in it. And the history of art, as we’ve learned here, certainly is very European-based and everything. And so, I sort of re-did a lot of iconic paintings as if I had done them. It’s pretty cheeky. It’s a pretty cheeky thing. So that became a book.

Then what I started during the pandemic was this book of women you should know, Original Sisters. And at this point I’ve painted 400 and they’re very simple. For me it’s more about the content. You know, it’s, “Why don’t we know about these women?” The woman who discovered the nature of the universe and all these women who are extraordinary and that they should be household names.

And so during the pandemic I started to paint one a day. And it was really, really inspiring. It was also inspiring painting one portrait a day of an extraordinary woman in a pandemic where we were asked to mask up and stay home, you know, big deal. What I was painting was women who endured the Holocaust, and endured wars, and did these extraordinary things.

So it was a very interesting project to work on at a trying time for us. So I went back to print, I thought when I reached a hundred, I thought, “I think this might be a book.” So I reached out to Chip Kidd, who I adore, and said, “Do you think this might be a book?”

And so it became a book and, you know, a foreword by Roxanne Gay, which was like, couldn’t get better than that. So that became my second book. But in the meantime, I kept going and I’ve done 400 portraits. It’s going to be at the Rockwell Museum next summer.

And hopefully it’ll travel, because it’s just really, it’s super interesting and I made it really fun. You know, it’s colorful, and there are pirates, and there’s all kinds of stuff. It’s for kids, it’s for boys, it’s for girls. It’s been really fun and it’s been really interesting. I used bright colors.

Anyway, for me it’s just something, this is different from my other work because it’s just purely information. You know, these are women you should know about. And then I have another book coming out in the fall, and I’m actually working on another one. I really wanted to do something that’s a thinly-veiled book about parables, and having to do with the time that we live in and gender politics and the environment. And so that’s what I’m working on now. So I seem to be, I’m straight back to print no matter what, where I don’t never go too far, but I’m, but I, right back here.

Six of the more than 400 portraits Kunz created for her book, Original Sisters.

“I constructed a career that allowed me to work for the people I wanted to and not for the magazines I didn’t want to. I had autonomy. That was part of it.”

Anne Quito: It’s the right direction. You’ve told me that you’ve started writing, and I guess this parable book could involve a lot of writing. How is that going? Are you okay calling yourself a writer?

Anita Kunz: Well, I’m not a writer. The women’s book was really just factual, you know, it’s historical nonfiction. So it was a matter of just trying to write just enough about the woman to get people interested in their accomplishments. So, I didn’t have to write anything more than to explain the person’s accomplishments and do it in a way that was concise.

But yeah, I’m not a writer. And I also do everything backwards. The parable book will start from the paintings. The paintings are the jumping off point. And then I don’t have to write that much because I’m not actually comfortable writing.

Anne Quito: I’ve heard you give advice to your students that it’s important to have some kind of fluency to explain your ideas, is to have words to sort of explain your concept.

Anita Kunz: Absolutely. Especially now. When I think back to when I was doing all the magazine work, I felt as though, especially with somebody—we’ve hardly talked about Fred Woodward, but he was so important in my career—but it seemed as though I worked with Fred and that was it. I’m not sure he ever went back to any editors. I think he just had the final say. I’m not sure how prevalent that is now, but it just seemed that I was working with Fred and that was it. And it’s quite a bit different now anyway.

Anne Quito: I read that Publishers Weekly described your books as “trickster feminism.” Are you okay with the label “feminist”?

Anita Kunz: Of course. I mean, the textbook definition of feminism is giving women and men the same rights and opportunities. Who doesn’t want a fairer world? You know? It goes to everything, doesn’t it? Differently gendered people or races or anything. Who wouldn’t want a more fair world?

Anne Quito: So you mentioned you started 40 years ago. I imagine you might have experienced some sexism during the early years? Is that something that lingers and something you want to, I don’t know, address now?

Anita Kunz: When I came up, I went to a school called The Illustrator’s Workshop, and it was always men, it was always just white men. And I think they, they brought in Barbara Nessim for an afternoon, the great Barbara Nessim. She’s wonderful. She’s amazing. And that was really the only contact I had with a female illustrator.

And even when I was teaching, I was always the only female. And I used to get asked all the time, “Why aren’t there more women?” I think I have more sophisticated answers now but at the time, I kind of just, you know, stubbornly kept working and I didn’t really consider that there were fewer female illustrators. For me there were always more female art directors.

But now, the older I get the more I see. Yeah, there were some pretty, pretty nasty things. You know what? I’ve made a giant painting and I’ve put all the terrible things that people have said to me into the painting. And it’s a picture of a woman and they’re, they’re kind of like little gashes and little tattoos and everything. Probably I will never show them to anyone but it, it’s kind of helped me think, “Wow. That wasn’t cool. That wasn’t cool. That wasn’t cool. That wasn’t cool.”

I think there’s still an awful lot of work to do. I think it’s certainly better. I mean, there’s so many amazing young women artists and designers, and I mean, just extraordinary, extraordinary.

And again, it’s just having the opportunity. Just give us the opportunity and we’ll do our best. But you know, part of the reason for the book was to showcase—“Okay, you haven’t heard of a woman scientist. How about this one?” It’s a sort of a love letter to the women who have gone before me who have not been recognized or have fallen through the cracks, or who were marginalized. So it all comes out in the work.

A 2004 cover for The New York Times Magazine.

Anne Quito: I imagine the books are opening you up to new audiences, maybe younger audiences. It struck me how generous you are to keep, I guess, reintroducing yourself. You have all the accolades. You are in halls of fame. But every interview I listen with you, you are generously, sort of, recapping your career.

Anita Kunz: I’m happy to talk about this stuff because we have a small field here, and I think it’s important to help people who are coming up in the field. I remember very well the artists who we went to see, or who were my teachers. I remember very well the ones who were generous and the ones who didn’t tell us what kind of pencil they used. Come on.

You remember this stuff. It’s not such a big world and. And I think kindness, especially kindness, is really important. The thing about different audiences, you know, I mentioned briefly that I tried to get into the art world for a while and you know, that was me really trying to find a different audience. But it didn’t work. It didn’t work until recently.

And this kind of maybe goes to, sometimes you want to do something and you just have to wait for the right opportunity. There is now a gallery, Philippe Labaune Gallery, in Chelsea, among all the really important, fine art galleries, and he shows narrative art, and he shows print art, and he shows comics, and he shows cartoons.

And, so I actually finally did get into a Chelsea gallery. And Philippe Labaune is French. He’s from Paris. And if you’ve ever been to Paris, you’ll see that every block has bookstores and they love comics and they love narrative art.

So maybe print is not dead. It’s in Paris.

Anne Quito: What a quote! It’s not dead. It’s in Paris.

Anita Kunz: It’s just in Paris. Yeah, it’s in France.

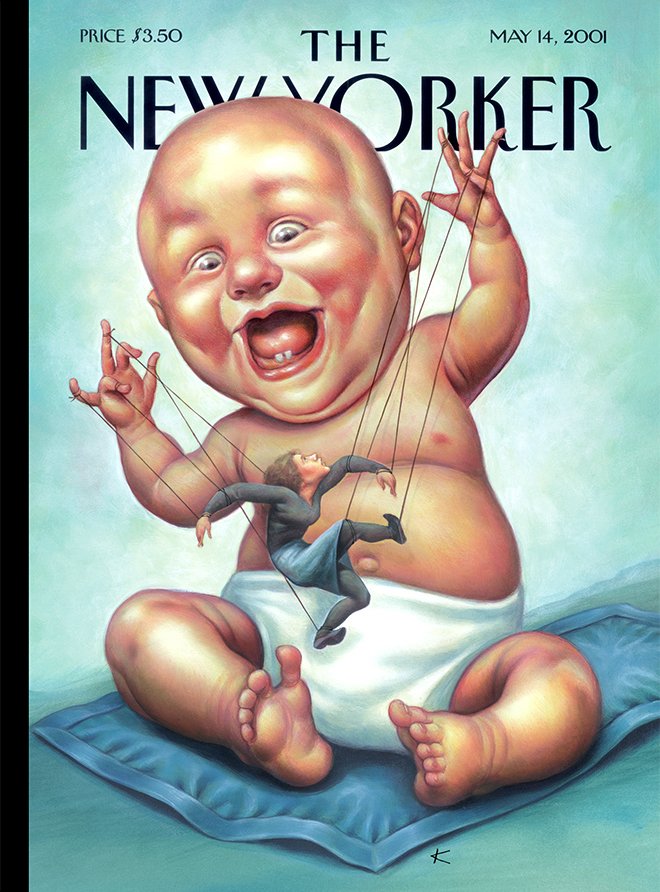

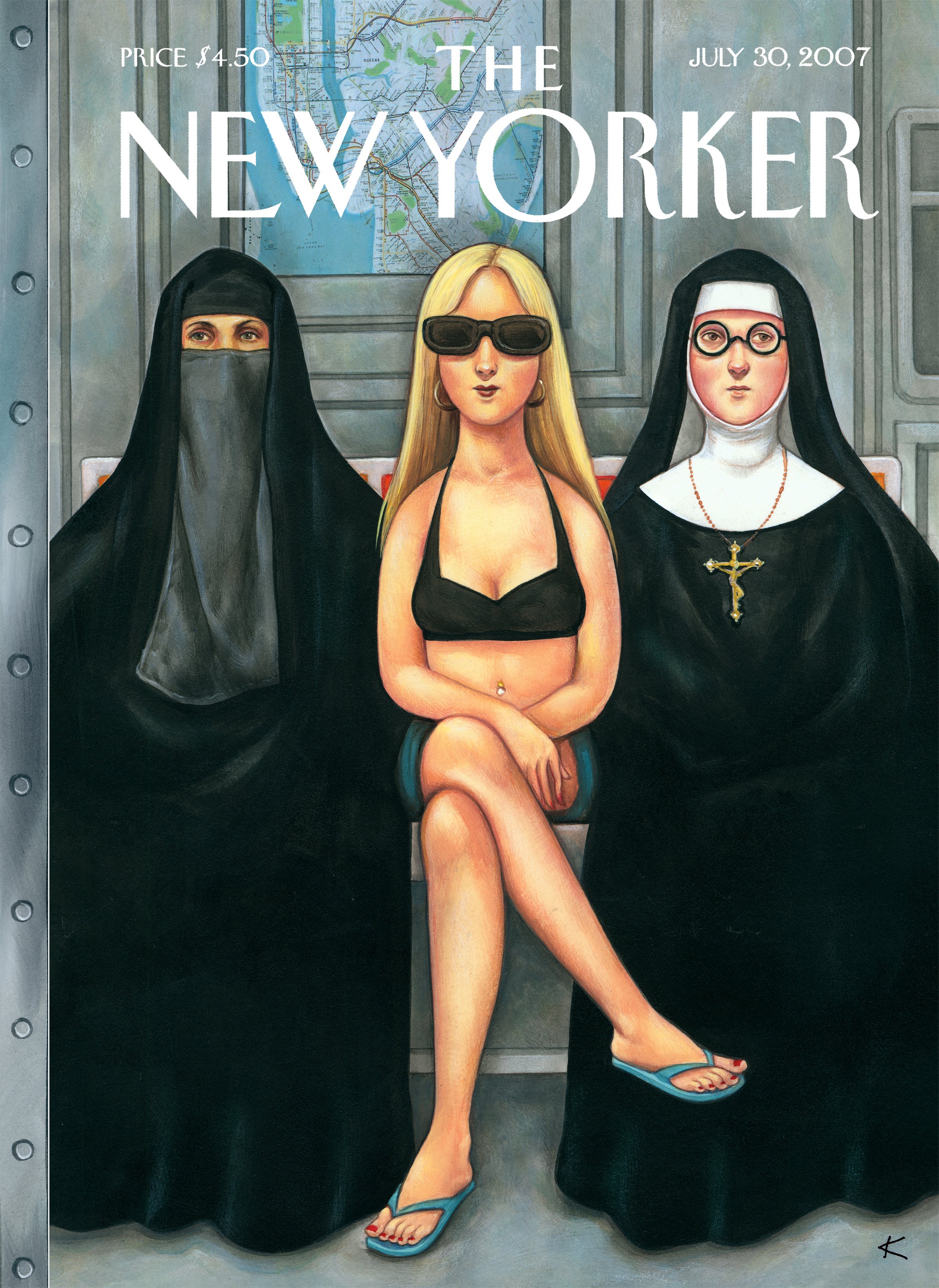

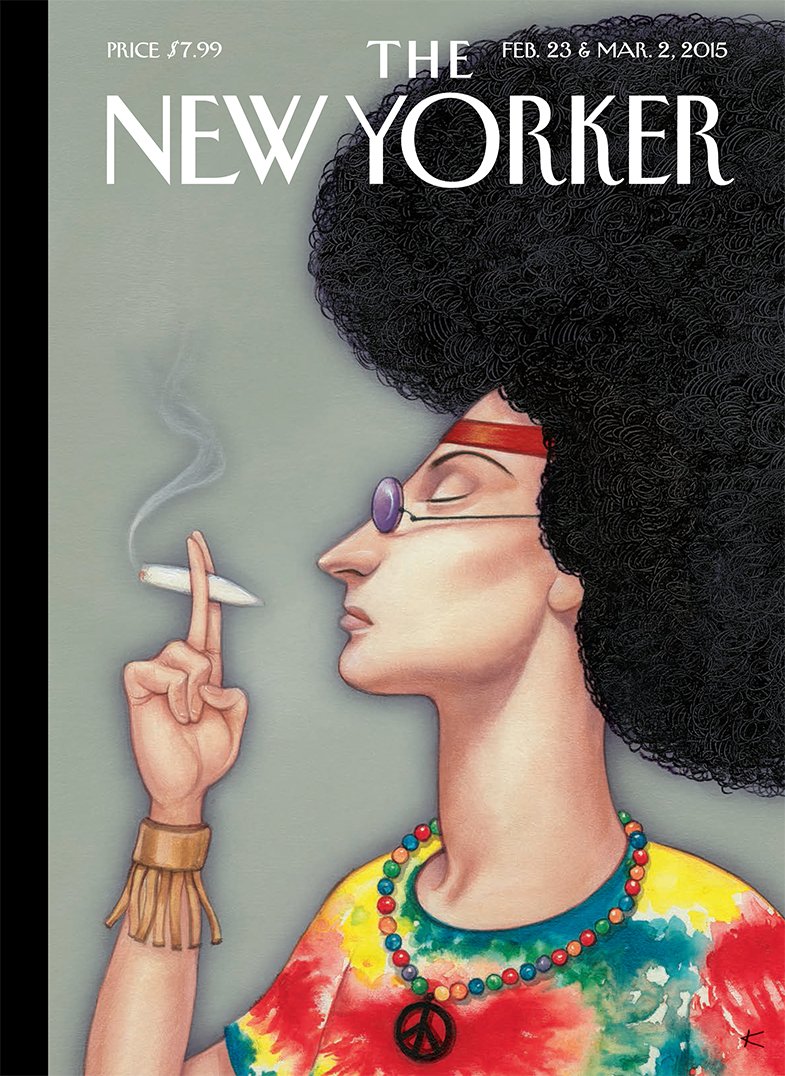

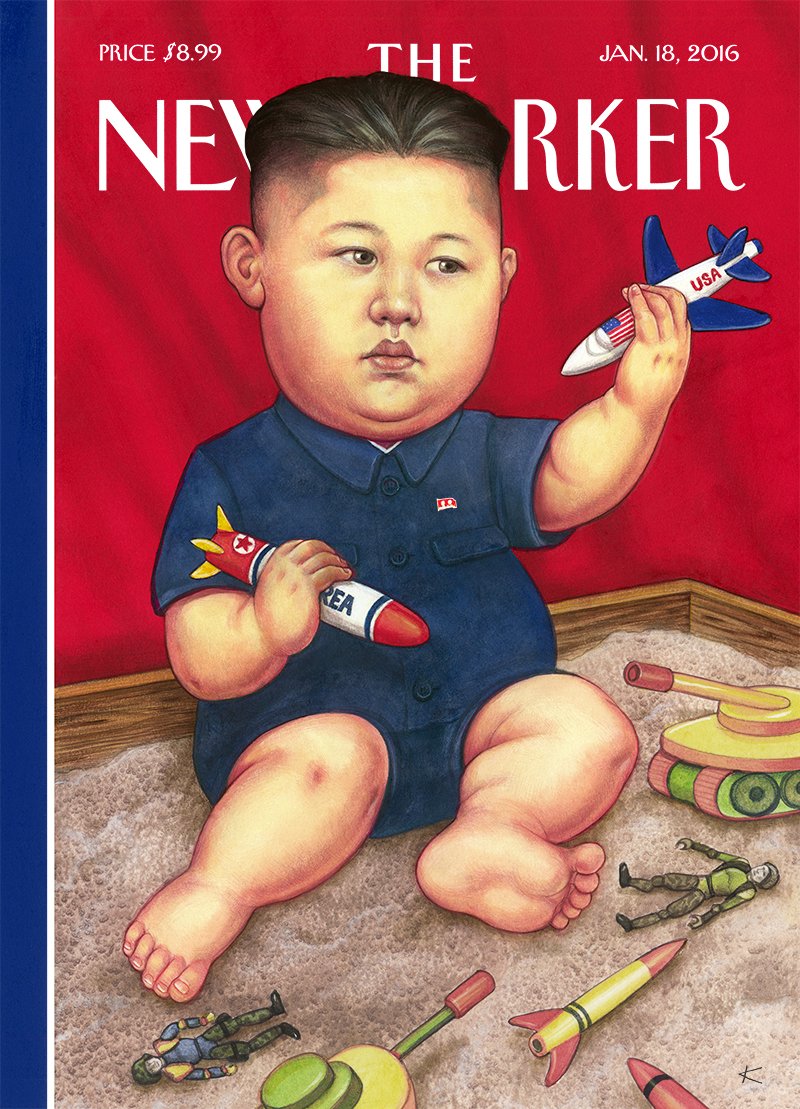

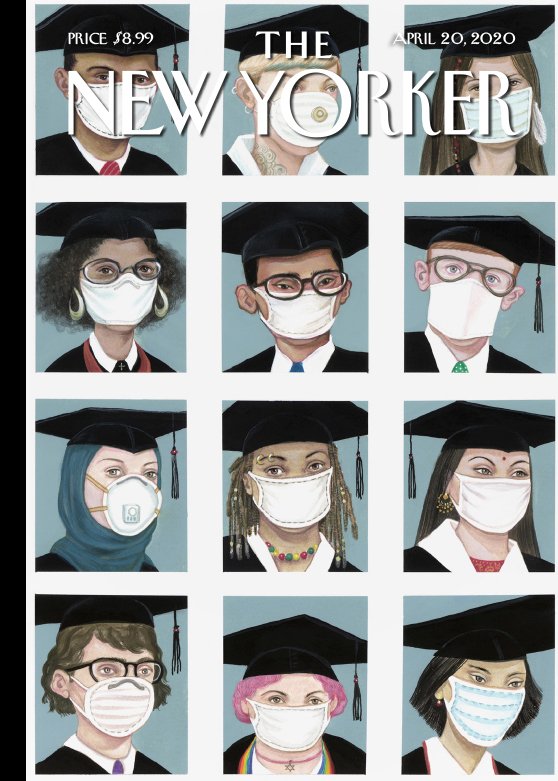

A collection of Kunz’ covers for The New Yorker.

Anne Quito: I love that quote, “Print is not dead. It’s in Paris!” I want to ask you about the future of magazines and editorial illustration. Right now we’re saturated with talk about generative AI. And there was this, I think it was Cosmopolitan magazine who made a splash saying, “Oh, we collaborated with OpenAI and generated the first cover.” How do you feel about this? Is this a threat? Is it an opportunity?

Anita Kunz: You know, somebody asked me to write an article about it, and I don’t feel I have the facts yet, 100%. But I don’t like it. I don’t like it because, you know, a lot of the internet has been scraped. And a lot of the material is copyrighted material. I don’t like it. I don’t know where it’s going to end. Somebody told me that my work is being used by one of the big companies, Stable Diffusion.

And somebody told me, “No, it’s not just the work, it’s your name.” Apparently, any artist who goes to some of these platforms, you can type in your name and, “Do such-and-such, a dog, in the style of Anita Kuntz.” Well, I don’t like it because now I’m competing with myself for something that I would charge such and such for, now it’s being done with no input from me. To me, that’s identity theft.

In season six of Black Mirror, the first [episode], I loved it so much, it was actually about this, it was about identity theft. Because illustrating, it’s not just about style, it’s not just about the picture, it’s not just about a cool visual pun. Illustrators are, hopefully, we know about the world. We’re intelligent. There is intent. It’s not just a cute picture that we’re going to slap here. There are any other number of things that compel an artist forward, you know, choice.

When I was an illustrator I constructed a career that allowed me to work for the people I wanted to and not necessarily for the magazines I didn’t want to. So that was part of the deal for me was that I was able to make visual opinions and again, I had autonomy. I mean, that was part of it. It wasn’t just someone taking an arm from here, and a leg from here.

The thing that bothers me more than just how I think it’s going to affect artists and writers is how it’s going to affect culture. An already divided culture. I don’t know how we’re going to get together and continue to have any kind of a stable democracy when there’s the potential for making any politician say something and nobody will know if it’s real or not.

Being an illustrator everybody knew it was a painting. They knew it was a visual opinion. But with AI, that’s the part that really scares me. Like when there is no such thing as truth that we can all agree on, then what happens to democracy? So I think it’s actually a much bigger problem than how it’s affecting my field.

I keep actually reading everything I can about it. It’s really fascinating to me. Because when I started in the field, I remember when faxes came out. Wow, that was amazing. You know, I was mailing things or FedEx-ing things. And when computers came out, or the internet, it changed everything. And I think this is going to change everything too, but I’m not quite sure how yet. So that’s the question of the decade or the millennium or whatever.

Anne Quito: My last question. How would you like to be remembered?

Anita Kunz: You know, I would like, I would hope that I’ve contributed more than I’ve taken away. And that’s it. I hope that I’ve done more good than harm. And I think that’s all I can expect. Everything else is gravy.

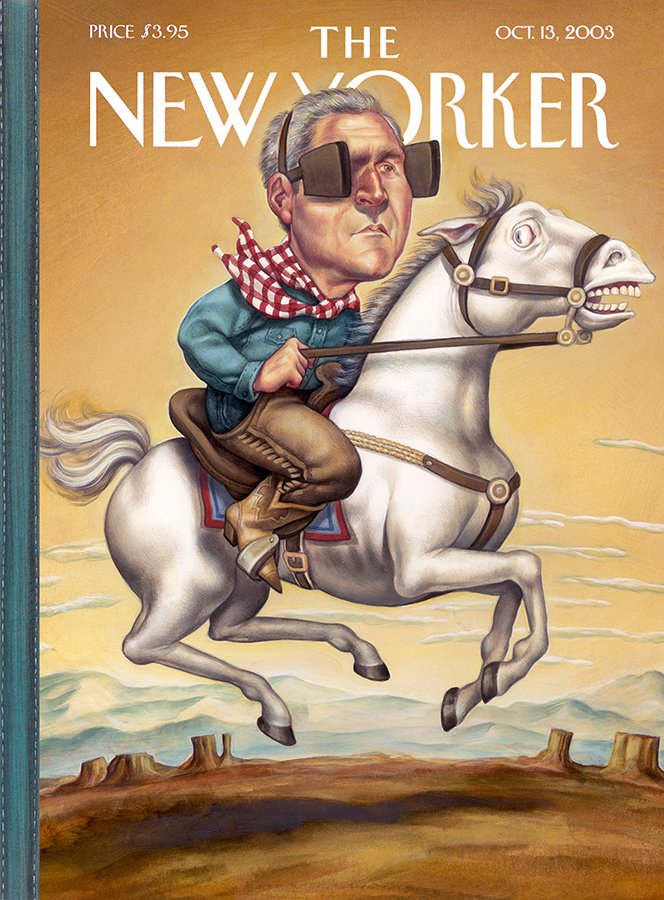

“Three Self Portraits with Facial Hair,” from left: Kunz as Albrecht Dürer, Frida Kahlo, and Marcel Duchamp (after da Vinci).

For more on Anita Kunz, visit her website or @anitakunz on Instagram. Her books, Another History of Art (Fantagraphics) and Original Sisters (Penguin Random House) are available wherever books are sold.

More Like This