Nice Guys Finish First

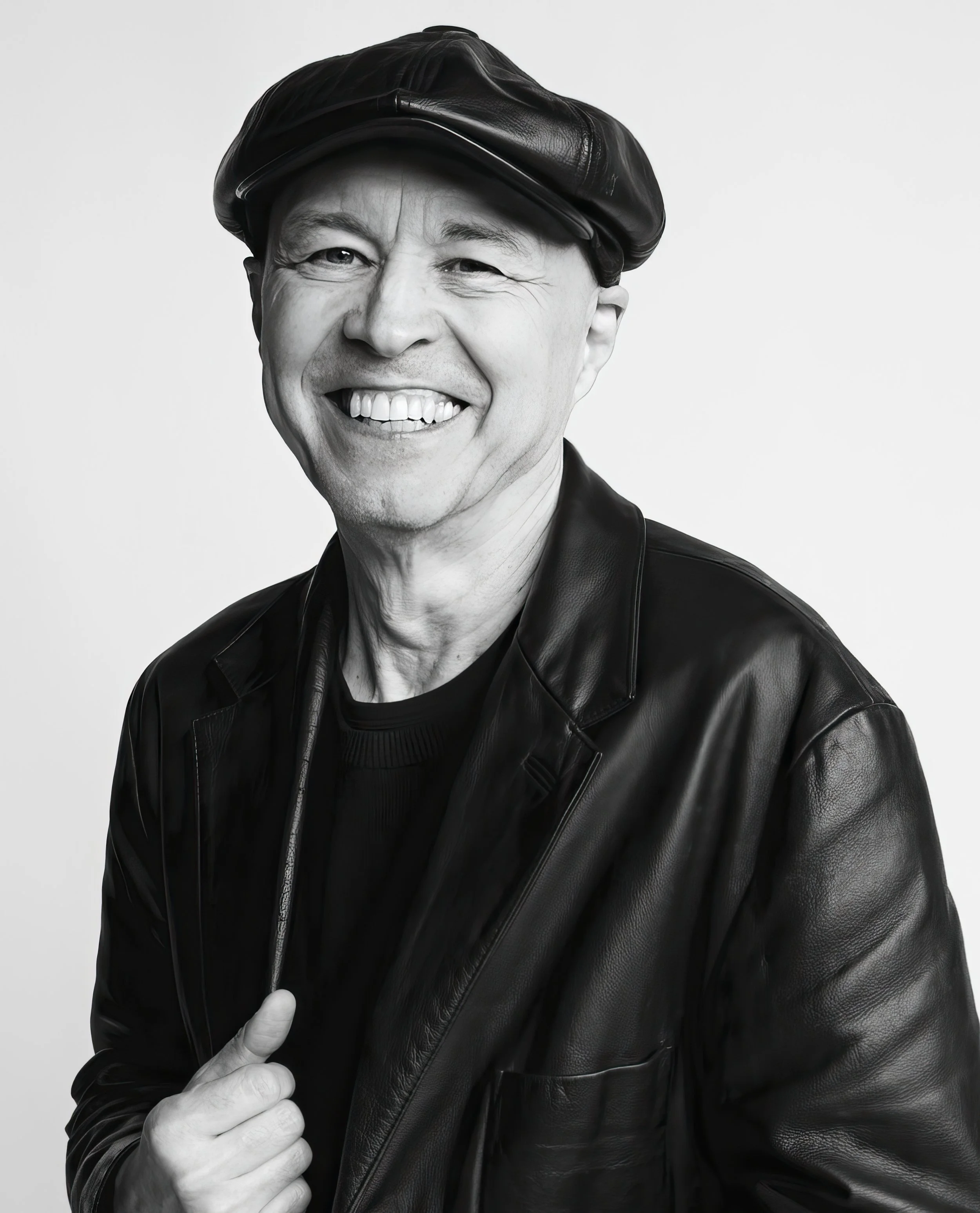

A conversation with designer Robert Newman (Details, Vibe, Real Simple, Entertainment Weekly, more)

To call designer Robert Newman “ubiquitous” might be an understatement. The entries on Bob’s resume are a name-droppers dream: The Village Voice, Entertainment Weekly, New York magazine, Details, Vibe, Fortune, and Real Simple. That’s enough brands for multiple careers, but Bob has worked on all of them—and quite a few others—in one lifetime.

And he’s still at it.

Despite all of the accolades, Bob is one of the nicest guys around. Those who’ve worked for him—and there are many—use descriptions like, “kind,” “supportive,” “mentor,” “constant,” “spokesman for our industry,” and “unwavering friend.”

Need proof? After a devastating injury in 2013 that put him in a coma for more than three weeks, Newman’s friends and fans rallied to raise tens of thousands of dollars to help pay for his mounting medical bills and treatment costs, and to help him support his family.

He’s a popular guy.

In 1998, along with Janet Froelich, Bob created the Magazine of the Year Award, given out annually by the Society Publication Designers, as its highest honor.

Patrick Mitchell: I would love to know about young Bob—”Little Bobby”—Newman. Where’d you grow up?

Robert Newman: Well, I grew up in a suburb of Buffalo. We actually lived in Larchmont also, because my father worked in New York for a few years, but mostly I grew up and graduated from high school in that Buffalo suburb.

Patrick Mitchell: Were your parents creative? Did any of what you would end up becoming come from them?

Robert Newman: My parents were very creative in their own way. My mother was a school teacher for many years, and my father worked for a chemical company as a purchasing agent. And to the extent that teachers are creative, I think my mother was always artistic on a certain level. But they never encouraged it in me.

Patrick Mitchell: Did you have siblings?

Robert Newman: I have one sister. She had career working for OSHA. A really great career.

Debra Bishop: What do you remember about the first moment that you realized that you were creative and that there was something special going on in your brain [laughs] that made you think that this was a career you might wanna pursue?

Robert Newman: Well, part of the problem was I was a terrible artist. I still am. I couldn’t draw. I was really uncreative in a traditional sense. Like I couldn’t think of things. I couldn’t draw. I couldn’t paint. I couldn’t, you know, make things. But what I always did was make posters. Even when I was little. And when I was a kid, my little sister and I would, when we’d go on vacations, we’d take all our toys and we’d put them all in the garage and we’d sell them to the neighbors. I would draw signs that I’d tack on trees and I’d take chalk and draw signs on the sidewalk that would say, “Come down and buy all this stuff.” And we’d sell all this crap—old baseball cards and comic books and dolls and stuff to our friends.

And then we’d get enough money so when we’d go on vacation, we’d have money to buy ice cream and whatever. So I always did signs and in high school I did signs all the time. I was a mad letterer. And I was the art director—although I didn’t know it was called that—of the high school arts magazine for two years when I was a junior and senior. So that was my first art director job.

Debra Bishop: I had the same experience like that. I knew that I loved typography and packaging, but I didn’t know what it was.

Robert Newman: I didn’t even know what an art director was. In fact, I can remember a friend of mine, after I’d graduated from college and went to work, he explained to me what an art director was. And I was like, “Oh really? They have people that do that stuff?” I had literally had no idea. And before I became an art director, I had about three or four other careers.

“Coming out of the ’60s, being involved in left-wing politics was cool. And in retrospect, I think that’s really where my interests in magazines and publications started because I was obsessed from early teens with the underground press and the left wing press. ”

Patrick Mitchell: Including political organizer.

Robert Newman: I did. I worked for a number of years as a political organizer.

Patrick Mitchell: Isn’t that what Barack Obama was?

Robert Newman: Yeah. It was kind of like that. I ran a food co-op in a small town in Ohio. We had a community organization that worked with low income people. In the early ’70s, there was a big recession and things were really miserable. Especially in the Midwest. We got a local farmer to donate 10,000 pounds of potatoes. We went to his farm and we loaded them on a truck and we drove the truck back and we put them in bags and then we put signs in all the bars and laundromats and churches. And the next day the people came and we passed out 10,000 pounds of potatoes to everybody, all the people in the community, which was great.

And that’s the kind of stuff we did. Then I moved to Washington DC and I worked on a political newspaper for about a year. I was actually the editor. It was a political group that was run by Dr. Benjamin Spock. And after that fell apart, I started working for the DC Statehood Party. That was a group of people that were organizing to get the statehood for DC. It seemed like it was close at hand back then, but it still hasn’t happened. And through that, I got a job in a local print shop. So for a year I worked as a printer in DC and that’s really where I learned to do pasteup and a lot of graphic design work as a printer.

Patrick Mitchell: Backing up, where did you go to college?

Robert Newman: I went to college in Ohio at a place called the College of Wooster. It was a Presbyterian religious college.

But I always did—going back to what Deb was saying—I always did signs and I always did lettering. And when I was in college, people would ask me to letter whatever… they would have bake sales or, you know, anything. I was always doing lettering. And people always knew my lettering. It was very distinctive. I still couldn’t draw, but I could letter like mad. I could just take a magic marker and fill up a big piece of board.

Debra Bishop: Were you like most kids growing up who were sort of artistically inclined? Was that how you got attention for being cool?

Robert Newman: [Laughs].

Debra Bishop: Your signs and stuff?

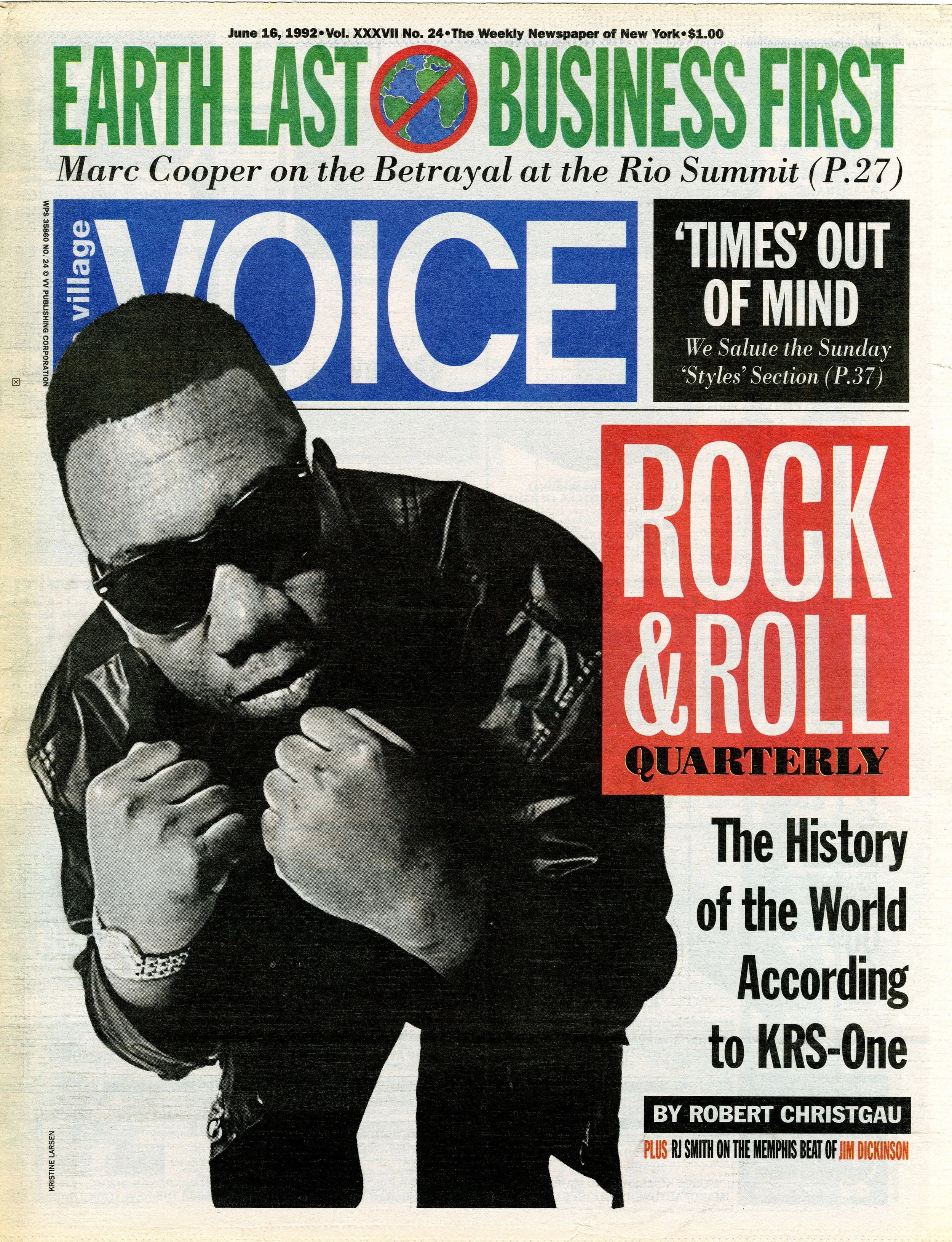

Robert Newman: No. I wasn’t cool. But what was cool back then, coming out of the ’60s, being involved in left wing politics. And in retrospect, I think that’s really where my interests in magazines and publications started because I was obsessed from early teens with the underground press and the left wing press. Like the Black Panther Party newspaper and The Village Voice and The East Village Other. And I was obsessed with those papers like crazy.

Portrait of Robert Newman by David Cowles

Patrick Mitchell: So you went from giving away potatoes to finally ending up in Seattle. How did you get to Seattle by the way? And talk about your experience at, I think, this was your first magazine job, The Rocket.

Robert Newman: Yeah. I got to Seattle because I moved out there in 1977. At the time, Seattle was the farthest possible place you could go. It was sort of like the “Go west young man!” kind of thing. Seattle had a good vibe back then. Everyone said, “It’s really cool out there.”

Patrick Mitchell: What were you trying to get far away from?

Robert Newman: At that point I wanted to do some kind of magazine or news, mostly newspaper. I wanted to do a newspaper like an alternative newspaper and they had a ton of them out there. I mean they had four out there at the time. They still had an underground newspaper out there. They had all kinds of stuff, and they had a really vibrant sort of alternative underground media scene. They had a Pacifica Radio station, and it was just a cool place. There wasn’t a lot like that on the East Coast. It just seemed like a place to move to where there would be a lot of opportunity. I was 23 and living was really cheap out there. Which also sounds pretty funny now.

Debra Bishop: Was that right after college or …?

Robert Newman: No, I spent a couple years in DC working when I did political work and working as a printer, and then I moved out to Seattle in my early 20s. And actually, The Rocket wasn’t the first place I worked, Pat. The first place I worked was an underground newspaper out there called The Northwest Passage. It was the last ’60s holdover. They voted on everything. Like, each page was designed by a different person, and they rotated. It was a collective and a different person designed the cover every issue.

And I kind of liked that idea. Then I worked on what they now call an alt weekly, but we didn’t use that phrase back then. It was a weekly community newspaper called The Seattle Sun. I started out as a production manager then eventually I became art director and it was, you know, like The Village Voice of Seattle. And at that point my dream job was to work at The Village Voice, which I eventually did. But I was really, really, really into working at a newspaper like that because it was so connected to the audience. And you would stay up all night and then you’d see the newspaper out on the street for sale the next morning and people would line up to buy it, and it was very exciting to see your work, you know, have that kind of impact right away. It was great. I loved that.

The great thing about working in a place like that is you would do like the worst thing and, and like everyone would forget it the next week. So it was great, you know, it was …

Debra Bishop: That’s a weekly … yeah …

Robert Newman: Yeah, yeah.

Debra Bishop: … where you can pound it out and, “Oh, gee, I may have like totally bombed this week… We’ll get…”

Patrick Mitchell: … “we’ll get ’em next week …

Debra Bishop: … Forget about it and move on.

Robert Newman: I mean, it would be so bad, and I’d be like, “Oh my God!” And then they would be gone in three days or something. And then you’d have a clean slate. It was great.

Patrick Mitchell: Then you ended up at The Rocket?

Robert Newman: Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: Talk about what The Rocket was.

Robert Newman: Well, The Seattle Sun was always a marginally-run operation and it didn’t make a lot of money and it was rooted in the Seattle hippie world. And things were changing culturally, you know. Punk was starting and a bunch of us at the Sun decided we’d do a supplement called The Rocket, which was a rock ’n’ roll insert.

We started it and we ran it for six months. And the Sun folks hated us. So we bought it from them and started on our own in a run-down little storefront on Capitol Hill in Seattle. And it was great.

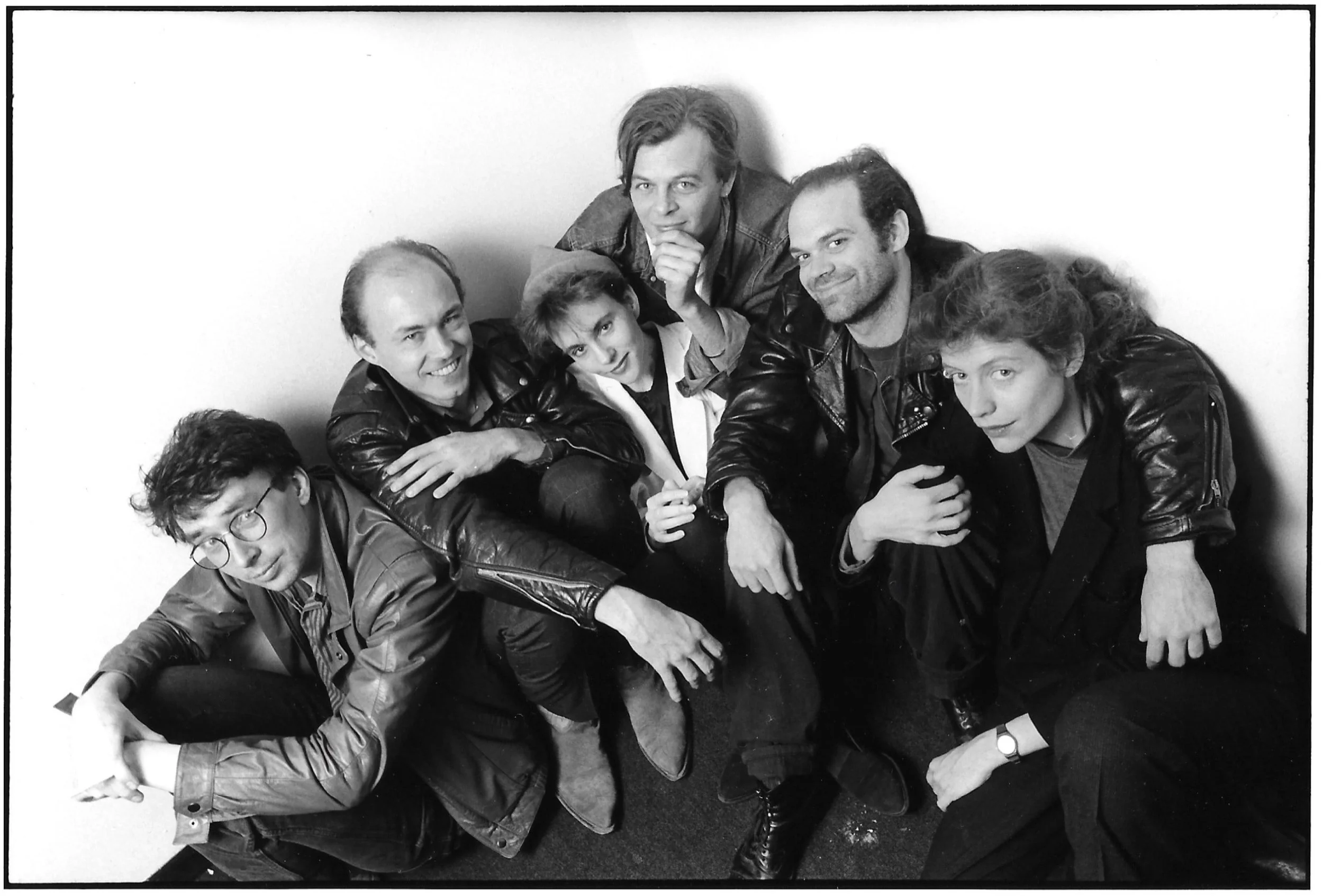

There weren’t a lot of good paying jobs in Seattle. It’s hard to imagine Seattle now—they have Microsoft and Adobe and Amazon. But back then, they didn’t, They had basically one job. And if you were an art director, there were no jobs. You had to make your own job. So The Rocket was us making our own jobs. And because so many of the people that started it were art directors, we had a rotating cast of art directors. Most of whom eventually moved to New York and did their own magazines.

Newman with his Seattle comrades (from left): Ron Hauge, Newman, Helene Silverman, Wes Anderson, Mark Michaelson, and Kristine Larsen.

Patrick Mitchell: To look at your bio on your LinkedIn page, I think it actually would be easier to list the magazines you didn’t work for than the ones you did. [Laughs].

Robert Newman: Well, the big problem, which you may or may not know—I don’t like to broadcast this fact—but every editor I ever worked for was fired after they hired me.

Patrick Mitchell: And not necessarily for making that decision?

Robert Newman: No. But I mean, every single one was fired. And sometimes fired, like the one at Entertainment Weekly was fired before I even got there [laughs]. Every single one: This Old House, Reader’s Digest, Fortune (twice), Real Simple, Vibe (she wasn’t fired, she quit), New York…

Patrick Mitchell: You know, you’re making an argument [laughs] that if I was an editor, I shouldn’t hire you.

Robert Newman: Yeah, that argument has been made, believe me. But, you know, it’s really hard to do a magazine without an editor who's a partner who you can work with and absolutely, you know, that’s the key and there’s different levels of that. Like, you can have an editor who just lets you do whatever you want. That’s the best, right? Or you can have an editor who’s, you know, a genius and inspires you or who’s an equal partner. I mean, any of those are good, but if your editor’s fired and you get a new editor, the odds are you’re not gonna be long for that world.

Patrick Mitchell: I read an interview where you said, and this is a quote, “I really like to move around. And I think most art directors would agree. You’re like a hired gun in a lot of ways.”

Robert Newman: That’s true. I do like to move around. I had two sort of dream jobs that I wanted to do. One was the Voice. And I did that for a long time. And the other one was Vibe and I did that, too. And besides those two, there were lots of really great jobs, but I have a pretty short attention span and I’m interested in a lot of stuff. And I liked that. I worked on a business magazine, a women’s magazine, an entertainment magazine, an urban fashion magazine, and an older person’s magazine. You know, I like the challenge of trying to adapt your visual storytelling skills to different audiences and try and get inside their heads.

I think the one thing is, I generally worked at places where I had an affinity for the audience. Vibe was the hardest one where I was most out of tune. Although the kids there really helped me a lot. But at each place I worked, I was really in the demographic of the magazine. So it wasn’t that much of a stretch. All I had to learn was the lexicon of what they were dealing with.

But part of it was too, I think it was sort of a challenge. You guys know this and we get this all the time. People would say, “Oh, well, you do women’s magazines. You can’t do Fortune.” You know, “You do entertainment magazines, you can’t do a fashion magazine.” Well, that’s not true. I think there are some people who have affinity for certain styles, but most good art directors I know, man, they can do anything. I mean, Deb, you may or may not have experienced this because you came up in women’s magazines. But for years that was used as an excuse to keep women from working at other kinds of magazines.

Debra Bishop: Absolutely. Absolutely. Totally. You know, I totally concur. It is hard for me to jump out of women’s magazines. Although, you know, I got my start in editorial design at Rolling Stone…

Patrick Mitchell: …Hard because of other people or hard because of you?

Debra Bishop: It’s harder to jump. You just don’t get those opportunities. You know, you don’t get a sexy job. And I think most women have the same problem. You don’t get a sexy job that’s about men’s fashion or, you know, because you’re a woman. And you can try, but it’s much harder to jump when you're a woman out of the women’s category.

Robert Newman: And that holds true for other genres too. Like, you know, I think people that have done hip-hop magazines would face the same kind of prejudice. I think trying to move to something like Fortune.

The Details art department (from left): Zoe Miller, Marlene Szczesny, Ronda Thompson, Newman (standing, rear), Alden Wallace, Markus Brown, and John Giordani.

Debra Bishop: You’ve worked with so many different editors. Is there one in particular that was your best partner or somebody that you worked really well with?

Robert Newman: I worked with Kurt Anderson twice, but only, unfortunately, for six months each time. Once because he was fired. And once because we folded. I worked with him at New York and I worked with him at magazine called Inside. That was part of the Inside.com. He was great. He was definitely one of the best editors.

The good editors, there’s lots of aspects of a good editor. And, as far as I’m concerned, the most important aspect is attracting talent, and keeping the talent happy, and making the magazine a community of joyful work and collaborative feeling. To me, that’s the number one key. And if he or she does that, then everything else is great. And Kurt was the best at that. At getting people in there, letting them do their thing and building this community of like really super-talented people.

The editor I worked with at Entertainment Weekly, Jim Seymour. Same thing. He was amazing. And he was another one who wasn’t threatened by young, talented people. He brought in young, talented people of all kinds and let them do their own thing. There’s this famous quote—which I’ve repeated many times—we were having this big argument about the cover one day in his office early on when I’d only been there a couple months. And he said, “Bob, this is how it works. You can do whatever you want inside the magazine. I trust you. You can do whatever you want to anything, but the cover is mine and you have to listen to what I tell you.” And I thought, “That’s genius.” You know, ”I can deal with that.” I want an editor like that, who has that kind of level of trust, but also who’s smart enough that I’ll say, “Okay, I trust you on the cover.”

I’ve had others too. I don’t want to leave any out, but there there’ve been plenty of others. Michael Caruso, who I worked with a few times. I worked with him at Details and at some other places, he was also really great. It’s really all about the editor. And you guys know that when you see a magazine where there’s this renaissance and the magazine is rocking and it looks great, start with the editor. Because in most cases you can’t do it without that person. And there has to be this insane level of trust so that when you pitch something, you’re not afraid to pitch it, no matter how crazy it is. And they’re not afraid to say, “Okay, let’s try it.” And at the same time, when they shoot you down, you’re not pissed off and go start stabbing people with an X-acto or something, you know?

Patrick Mitchell: Uh, tell our young listeners what an X-acto is [laughs].

Robert Newman: [Laughs].

Debra Bishop: … a blast from the past! [Laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: Michael Caruso was your editor at Details, right?

Robert Newman: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: So Details was, I think the first place where I became aware of you. I actually used to buy Details before you did it. If I recall correctly, it was a black and white magazine printed on sort of cream-colored paper.

Robert Newman: That was back in the day before Condé Nast bought it. And then Condé Nast started running it, and they had a series of really talented art directors.

Patrick Mitchell: The work you did there, I would say it’s the first time I really had an appreciation for the process of a redesign. You had a concept that involved the inspiration of Blue Note Records. Talk about what your process was to get to that look.

Robert Newman: Well the thing about Details—and I loved what we did there—is it’s the classic example of how you really need a collaborative team all around to really make it work. We had a brilliant photo editor, Greg Pond, who was just amazing. And we had a brilliant fashion director, Derek Prokope, who actually had worked at Vibe before he worked at at Details. And we had Michael Caruso, who was really supportive and we could go in and just pitch anything and he’d go, “Yeah, that sounds cool.” And the staff was young and talented and deep and diverse. All of that helps, you know. It was definitely one of the most diverse places I worked except for Vibe. Maybe were you up for that job? Everybody was up for that job.

Debra Bishop: I certainly wasn’t [laughs].

Robert Newman: I know a few people who were up for that. Anyway, Michael was like, bless his heart, he cast a wide net and he made everybody do a pitch. It was very corporate. And if you were up for it, Pat, I wouldn’t be surprised. And I went in and just did this pitch and, you know, remember those Blue Note books had just come out?

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. Big, album-sized books.

Debra Bishop: Yep. I have them.

Robert Newman: They were paperback, album-size books. To tell you the truth, it’s not like I was a student of that stuff. I’d never heard of it until I saw those books. And suddenly I was like, “Oh my God, I could do this.” And that was always one of my things. In fact, Pat, you come into this because I used to always look at stuff, and you were one of the guys I used to look at and go, “I could almost do what he’s doing. It’s, like, in my world.” And so when I looked at Blue Note, I looked at that stuff and I thought, “I could do that.” And it kind of happened. It’s kind of Ocean’s 11 kind of that stuff, lounge-y stuff was really in back then in the later ’90s.

Debra Bishop: It was in the air.

Robert Newman: Yeah, yeah, yeah. So we pitched that to Michael and he went for it and, fortunately, Greg Pond and Derek Prokope, they really went for it. They just delivered these pictures and fashion spreads that were all about that.

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. A lot of people might have had that same inspiration from those books, but they would’ve applied it to the wrong place. It was perfect for Details.

Robert Newman: Yeah. And then, of course, Blue Note came and threatened to sue us if we didn’t stop [laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: Wow.

Robert Newman: We did four issues. So we sort of had to pivot a little bit and we got into this, “We’re influenced by this, let’s be influenced by that.” So we started being influenced by a little later stuff like Saul Bass stuff and ‘60s hipster stuff.

Patrick Mitchell: But all in the same world.

Robert Newman: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Debra Bishop: If we want to get more granular about that kind of thing, what is your favorite part of making a magazine? And your least favorite?

Robert Newman: I really like working on the covers when I have that kind of freedom to work on them. Unfortunately, and this is not a criticism of any particular magazine, but the kind of freedom that one has these days is much more limited by commerce and a lot of other things. I used to really like coming up with covers that really connected with people back in the day when we actually sold magazines on newsstands—and sold a lot of them. We did a lot of cover testing. I really liked that a lot. When I worked at Real Simple and at Cottage Living, we did a lot of cover testing. Both coverlines and cover images. You probably did a lot of that, Deb.

Debra Bishop: Oh yeah. So is it the stuff related to business that you like the least? The conceptualizing that you like of the covers, and the drudgery of coverlines that you like the least?

Robert Newman: It doesn’t bother me. In fact, I’m usually the one who’s arguing for more coverlines, because I like to really trash it up. What I like about the cover is—what I really like about magazines in general is—I like the work that connects with people and that really opens a communication with them. That’s always what I liked about it. When you, as a visual storyteller, an art director or creative director or whatever you wanna call it, you’re really opening up this conversation, a visual conversation. But it goes beyond that with people directly. And you know, it wasn’t about selling copies because I wanted to make money for Time, Inc. I could have cared less. It was about reaching as many people as possible.

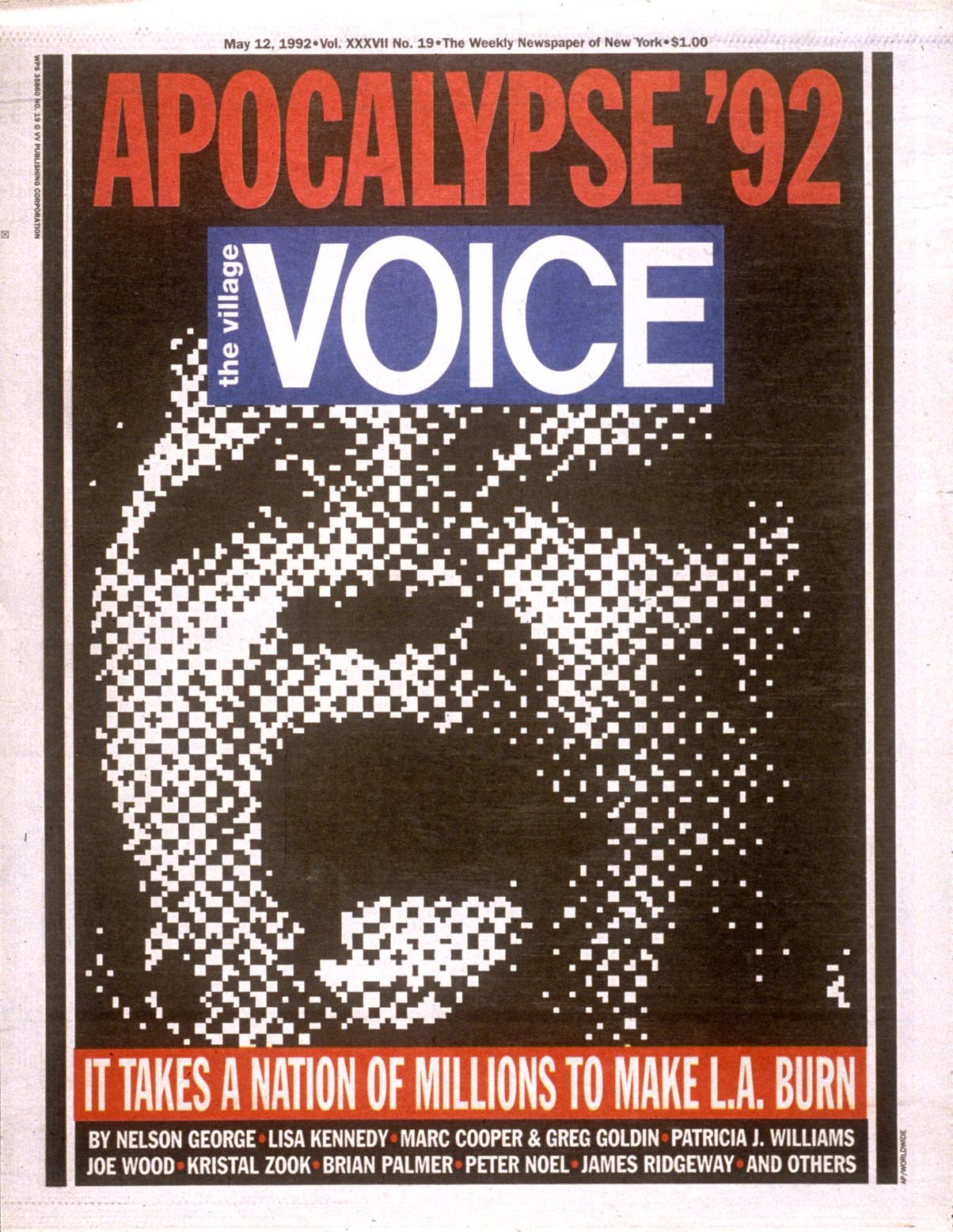

When I worked at The Village Voice, what I used to like to do is go down and walk around and look at the newsstand on Wednesday morning and just stand there and watch people buy it, and see how they reacted to it. I really enjoyed that part of it. Whatever part of the magazine touches on that is my favorite part.

I would say my least favorite part is, I don’t know. I just don’t work that well with editors [laughs].

Debra Bishop: I think the majority of art directors would say the same thing.

“As a visual storyteller, an art director or creative director or whatever you wanna call it, you’re really opening up this conversation, a visual conversation. But it goes beyond that with people directly. It wasn’t about selling copies because I wanted to make money for Time, Inc. I could have cared less. It was about reaching as many people as possible.”

Patrick Mitchell: I read a lot of stuff about you, you know, I try to be as prepared as possible. In Mediabistro, Greg Lindsay, who really loved covering magazines, wrote that there is no such thing as a Robert Newman “look.” And I think he’s right. How do you think about that?

Robert Newman: Most of the places I worked, I inherited pretty strong visual directions. They already existed. When I went to work at Entertainment Weekly, I inherited a design by Michael Grossman. That was just superb, sublime. And a lot of places, rather than redesigning, I just kind of developed a look based on the DNA of what was already there. I’m not that original of a designer, I have to tell you. It’s just not my thing. That’s not my strong suit. I think Details was a rare case where we came up with something really original and threw everything out. But usually I don’t.

And I’ve also had a lot of really strong number two designers, art directors, and have deferred oftentimes to their skills, because they just had way better chops than I did. When I worked at EW first, J. Armus, and then George Karabotsos, and Michael Picon, and Joe Kimberling, and Florian Bachleda were my deputies, and I just couldn’t touch their chops. I just let them run with it and I had no problems with that.

Patrick Mitchell: And you could make the argument that having a look is kind of lazy because I think you’re right. I mean the whole thing from the time you learn design is to design something specific to the audience and to the DNA of the magazine.

Robert Newman: I think I have a look. I think my look, with the exception of—now my look is much simpler—has always been basically simple and at times I’ve been influenced by all the stuff you guys did at Rolling Stone, Deb. That kind of skeuomorphic design that you guys did so well. I have to control myself to not go there, because I find it so alluring. It’s like a drug, you know?

I think my own look, if there is a look, tends to be simple and big and bold. But a lot of times, people didn’t want that. People wanted—I’m sure you had this, Deb, when you left Rolling Stone, and I had it when I left Entertainment Weekly—everybody wanted Entertainment Weekly after I left Entertainment Weekly, and you know, I didn’t want to do it because it wasn’t really inherently my thing. But they all wanted it. I’m sure you, Deb, after you left Rolling Stone, everyone wanted you to be Fred Woodward, Jr., or something.

Debra Bishop: At times. And I think it wasn’t always appropriate.

Robert Newman: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: It had its own life at Rolling Stone and not appropriate for a home magazine, for instance, that should be more photography-driven. So that was a bit of a weird thing for me.

Robert Newman: It’s funny when we talk about styles. I was looking through some old magazine stuff to study up for this and, you guys know this, so many magazine styles get so dated so fast. And we all have our embarrassing moments. All you have to do is go back to the ’80s and you’ll see a lot of really embarrassing moments. And like in the ’90s, once desktop publishing started. But you try to find styles that are timeless. I have to say, both of you guys are really geniuses at that. And I really admire both of you because when I look at your old stuff, it looks like it was done today. And it’s timeless. Not a lot of people can do that. And the magazines when I look back at the archive, you cringe when you look at them you go, “Ugh.”

Debra Bishop: Sometimes I cringe [laughs].

Robert Newman: You might cringe. But most of it you don’t. You have timeless stuff and if you can get that sort of timeless look—I think that’s really what defines a great publication designer—that from beginning to end, they don’t look like they were trendy at any point. They just look like they stayed true to themselves and their look was unique and original and worked from beginning to end. And that’s what defines a great designer. I’m not at that level. I have to say, I’m just a copycat. I’m just a stylist. And I’m proud. I can copy anything, and I like to copy [laughs].

Debra Bishop: Okay. It’s time to close your eyes and think about Bob Newman. Where are you sitting? (Of course I can see where you’re sitting). [Laughs]. What are you doing? What are working on?

Robert Newman: At this moment in my life? What am I working on? Well I’m working at home. I’m doing all my work remotely now. And I have been for the last two years. I’m working as creative director of This Old House magazine and, theoretically, I’m also directing a bunch of digital stuff that they do. But I think I can safely say I don’t love doing that. And I try to delegate as much of that as I can.

Debra Bishop: I had a question that we kind of skipped and maybe this is a good segue into it, in that I’m trying to do digital now, too. And I’m just wondering, you know, how you feel about that. What makes is a good UX designer? The same as a print designer? What are the differences?

Robert Newman: That’s a good question. I think print designers have something really unique and that’s that they’re editorial designers and they think holistically about the content and the design. They’re visual storytellers. I’ve used that phrase before, but that’s what they are. And they’re also curators, which is what you learn when you work in a magazine. And they’re also very functional and that’s where they intersect with UX, because UX is obviously all about function. And my problem with UX is that there’s no art. It’s all commerce and function. And there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s just that I don’t want to do that. And also with UX, it’s very scientific and there’s nothing wrong with that, either.

But what I like about magazines is that periodically people get a chance to expand the envelope and expand the language and expand the way people think, and you can be noticed. But the thing about UX is, you’re not supposed to be noticed. And I’m sorry, but I'm an egotistical asshole, you know, and I wanna be noticed [laughs].

Debra Bishop: That gets back to the “being cool” thing…

Robert Newman: I wanna be noticed. And not only that, but I want…

Debra Bishop: …You do like to be cool. And it is something special to have people see your work and love it. It’s wonderful to work on a visible project…

Robert Newman: But it’s not only about me. It’s about wanting to—and this probably goes back to my whole, you know, my little political career, which wasn’t that successful—it's about wanting to impact people. And I think one of the things about magazines is that the visual people in magazines tend to be more socially conscious and empathetic. And they care about stuff. The art directors and photo directors and production people and artists and illustrators and photographers—they care about things and they care about people and they want the world to be a better place. And the work that they do, ultimately, most of them want their work to contribute to a better world on whatever level that means. And you know, that was always why I liked working at magazines. Partly because you can make the world a better place. I don’t see UX design doing that. I think it makes people money and that’s fine. You know, that’s why I don’t have the future in that field—as my boss constantly reminds me [laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: I don’t want to expand on my feelings about UX and the whole digital thing, because…

Debra Bishop: That could go on all night!

Robert Newman: [Laughs] No, I mean, I think the thing about UX that’s interesting to me is it’s problem solving and it’s functional and you know, so it’s…

Patrick Mitchell: But it’s not magazine design. And it’s not even really creative either.

Robert Newman: No, it's not creative. It’s more technical.

Patrick Mitchell: It makes me mad. And when I get mad, I swear. And I want to talk to you about swearing, because it’s a fundamental skill in the magazine business.

Debra Bishop: We haven’t heard any swearing yet!

Patrick Mitchell: Not enough!

Debra Bishop: Yeah! [laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: Do you have a preferred swear? Is there a greatest swear you’ve ever heard?

Debra Bishop: Are we gonna get censored?

Robert Newman: Well, here’s the thing. I worked at The Village Voice and I worked at Vibe, so I heard a lot of curse words. But since working at Real Simple and I worked at AARP and Reader’s Digest and This Old House … you can see where I’m going with this, you guys. Not only were these magazines where the readers were older and the environment was more sedate, but they also were predominantly female staffs. I’ve had problems with anger, believe me, at work. And I try not to be that guy who curses, you know? And so I didn’t curse.

Patrick Mitchell: Hey, I learned everything I needed to know about cursing from a woman who worked for me, so…

Robert Newman: I just don’t, I mean…

Patrick Mitchell: Trust me, it’s not a gender thing.

Robert Newman: I have two kids, you know. I’m still shocked when they curse in front of me. And listen, I’m all for putting curse words into the magazine.

Debra Bishop: Well, there must be some expletive there that you like to use.

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. What’s your favorite?

Robert Newman: My favorite curse word?

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah, what’s the one that comes most naturally? Mine’s “motherfucker.”

Robert Newman: Well, yeah, that would probably be mine, too. [Laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: What’s yours, Deb?

Debra Bishop: I don’t know. I’m sitting here trying to figure out what it is.

Robert Newman: She’s Canadian. They don’t curse.

Debra Bishop: I have a lot of funny sayings that I’m sure drive people crazy, like, “Oh, you wrecked it!” I have to say I probably prefer the “F-word” because people aren’t expecting it to come out of the mouth of a, you know, a little girl from Canada.

Robert Newman: And also [laughs] the acceptance level of curse words has expanded so much that really the “F-word” is the only one that’s left because, I mean, everything else is printed. I think that The New York Times, except for The New York Times for Kids, The New York Times probably prints every word imaginable.

“Visual people in magazines tend to be more socially conscious and empathetic. They care about stuff. They want the world to be a better place. And [they] want their work to contribute to a better world. I always liked working at magazines because you can make the world a better place.”

Patrick Mitchell: Swearing serves its function [laughs], but prevailing wisdom says we learn from our mistakes. What is the biggest mistake you’ve ever made at work?

Robert Newman: Probably the biggest mistakes were not hiring somebody. But you don’t mean like that. I think there were a few times I should have hired somebody that I didn’t, and I’m still really embarrassed about that.

Debra Bishop: Now that we’re really getting into the nitty gritty, you can’t have been in this business for that long without being fired, right?

Robert Newman: Oh, I was fired many times.

Debra Bishop: So what’s your best “getting fired” story?

Robert Newman: This goes back to Michael Caruso. I owe this all to Michael Caruso. When I was hired by him at Details, he said, “Dude, you gotta have a severance letter.” And I was like, because I was an art director, “What is that? How do you do that?” And he said, “Look, I’ll show you how to do it.” So he showed me. And then I had a severance letter. So [laughs] after that, you know, Condé Nast bought my weekend home when they fired me, which was great. And then when Fortune fired me, that sent my first kid to college. I got severance three or four times.

Having severance was great. But I don’t have it anymore, unfortunately [laughs]. I mean, I’m joking about it, but I also think it’s really good. You shouldn’t have to worry if you get fired. You shouldn’t go through life having to worry, “Oh, I’m going to get fired. What’s going to happen to my kids? My house?” If you have severance you can just do your job. And if they don’t like you they fire you and you’re fine. And you have a cushion and, and that’s the way it should be.

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. I’ve never heard of a sort of proactive-preparation-for-getting-fired letter.

Robert Newman: Well, you just have a severance. They fire you, you get, whatever, six months…

Patrick Mitchell: But you write this long before you get fired?

Robert Newman: Yeah. That’s part of your deal when they hire you. That world doesn’t exist anymore.

Debra Bishop: Yeah, exactly. I haven’t been fired, but I’m wondering, in this climate, do you feel like people are constantly worrying that they’re going to be fired?

Robert Newman: They should be. Yeah. I would. I worry about it every day. I mean, it’s never pleasant to get fired. And I had a combination of my magazines folding and getting fired.

Debra Bishop: But a magazine folding isn’t really getting fired.

Robert Newman: Yeah. But it helps to get severance when it folds [laughs]. That’s always good.

Debra Bishop: Yeah, exactly. But getting fired is like, “Nope, we’re moving on.”

Robert Newman: You know how it goes. Well, you don’t Deb, if you haven’t been fired, but generally they fire you on a Thursday. That’s pretty common. And they call you in and they say, “I need to have a meeting with you.” And you walk in, and if you see the HR person there, you know where this is going. Oh boy, you know.

Patrick Mitchell: In 2013, you suffered a traumatic head injury that put you into a coma and on a respirator for almost three weeks. Can you talk about what happened?

Robert Newman: Well, I fainted. I was on a trip with my daughter and I fainted and hit my head and I suffered brain injury. And I had a seizure. And so, yeah, you’re right. I was a coma for almost three weeks.

Patrick Mitchell: Did you just go out cold at that moment?

Robert Newman: No, actually I passed out and hit my head and then I woke up and then they came and put me in an ambulance and I passed out before I got to the hospital.

Patrick Mitchell: Where where were you working at this time?

Robert Newman: I was a freelancer actually. I’d been fired by Reader’s Digest and I was freelancing.

Patrick Mitchell: So this is the worst possible moment that something like this could happen.

Robert Newman: Yeah. Fortunately I had insurance though. My insurance was still going.

Patrick Mitchell: And you had two young kids?

Robert Newman: Two young kids. Yeah. And I was a single parent because I was separated from my wife.

Patrick Mitchell: So three weeks in the hospital without waking up.

Robert Newman: Yeah. In fact, Scott Davis at AARP sent me an old, moldy copy of Fortune from the ’30s with a note saying, “Put this under Bob’s nose while he’s in his coma, and the smell of the magazine will bring him back.” They were putting this old Fortune under my nose while I was laying there [laughs].

Debra Bishop: It was inspiring to see how the community rallied to your aid. How are you now?

Robert Newman: Well, I’m pretty good. I’m at the age where I don’t want to complain about any health things because I know people that are no longer with us, so I’m just happy to be here. And people were really super. I mean if I hadn’t gotten that kind of support, I don’t know what would’ve happened, because my kids were both in school.

My Favo(u)rite Magazine was part of a fundraising effort to support Newman and his family after he suffered a devastating injury in 2013.

Patrick Mitchell: And this was really before things like…

Robert Newman: It was the early days of the kind of GoFundMe thing. In fact, I don’t think GoFundMe even existed. I had no idea. I forget who put it together. It was probably Michael Grossman. He was involved. And Jeremy Leslie was involved. And Jill Armus.

Patrick Mitchell: As terrible as the injury and the tragedy and the situation you were in, it must make you feel so good that so many people thought so highly of you that they rallied to help.

Robert Newman: It was pretty amazing. It did. It made me feel great. It was really touching and there was a lot of love. People freak out—I experienced this when I was younger, in my 20s. I had a life-threatening illness. And people freak out when people their age are close to death. When you’re younger, you just don’t expect your contemporaries to die.

Patrick Mitchell: It is shocking.

Robert Newman: When someone your age—one of us—gets really sick, it’s shocking. I mean, I’m not diminishing what people did, but it's shocking. It’s like a shock to the system. But I love what they did. It was just great.

Patrick Mitchell: And it wasn’t just in this country. Didn’t Jeremy Leslie at Magculture put a fundraiser together in the UK?

Robert Newman: Yeah. And it’s the best kind of tragedy, where great art comes out of tragedy. They put together a magazine called My Favo(u)rite Magazine that was a collection of people’s favorite magazines from back in the day. It was great. It was a great piece of art and they collected a ton of money. I mean, I can’t tell you. And I had no money. I was living like a freelancer. You know how it is: paycheck to paycheck, basically job to job. And I couldn’t work. It wasn’t so much being in the hospital, but I couldn't work because I couldn’t walk. I came out and I was in a wheelchair and I couldn’t work for about a year afterwards because my brain was so messed up. (And it still kind of messed up, to be honest). I’m not looking for sympathy.

Debra Bishop: But I’m sure that there are some challenges coming back—and the fight to get back to work and feel somewhat normal.

Robert Newman: Yeah. It took a while. It definitely took about a year. At the time I was working with a partner, Linda Rubes, who was both my life partner and also work partner. And I would try working on projects and she would say, “You know, you’re not, you’re not there.” Like, you know, “You can’t do this, you know?” And I just couldn’t. When you have a brain injury, you just can’t get to that place that you want to get to. It’s hard to explain, but I just couldn’t sustain work for a really long time. It was great that people helped me out. It was so great. So amazing.

Patrick Mitchell: Can you mark the point where you felt kind of back to normal?

Robert Newman: When I got hired at This Old House, which was about two years or so after my accident. I couldn’t do freelance. It just was too hard for me. I just couldn’t focus on it. I needed to be in an office with people and to have a rhythm to get back into. And when I started, this was maybe about two and a half years after, when I started working that saved my life. I mean, besides the everyone chipping in, that really saved my life. Going to work when Scott, who was the editor, hired me at This Old House, that just saved my life.

Debra Bishop: Bob, I think the first time that I actually met you was at SPD. You were running Magazine of the Year and I was doing Martha Stewart Baby. How many years have you actually been running MOTY at SPD? And what’s that been like and how has it evolved?

Robert Newman: Well, we started it, I think, when I was at Details and Janet Froelich from The New York Times Magazine and I were the co-chairs. It was probably like, SPD … I wanna say 33 maybe? And they’re up to 57. So it’s been that many years. It’s 22 years.

Patrick Mitchell: You were there at the beginning.

Robert Newman: Janet and I thought it was odd that they didn’t have kind of a finale, drumroll kind of moment at SPD. They just gave the awards and then everyone split to start drinking and stuff. And we wanted to have a “love bomb” at the end. Like, “And now…” You know, the grand finale. And we thought “This’ll do it: Magazine of the Year!” It meant a lot more back then than it does now. And I think it worked. Over the years, I think, generally the right magazine has won. It’s been their time when they’ve won. I mean, obviously with any awards, there’s problems. People have a beef with it. But in general it’s been a great acknowledgement of who's just the doing the star work that year.

And I mean, I’m always happy. It's really been a great award and a great acknowledgement. I don’t think it’s changed that much, Deb, when I think about it. The biggest problem has been that it’s dominated by the same 10 magazines or 10 art directors. Right? But you know, that’s the case with all awards. And the one thing that changed is, a few years ago we expanded to Brand of the Year. And given the nature of publishing, we’re trying to make BOTY the ultimate award and MOTY is now the second biggest award.

Patrick Mitchell: It’s hard to argue with the fact that the magazines that win the most awards do represent the best work being done. I mean, you have to think about the people who can’t afford to enter.

Debra Bishop: I don't think there is another award for art directors, the head of the magazine team, I don’t think there is an award that has really ever meant so much. I know it has evolved and BOTY is now a reflection of what we all do, which is not just print, but Instagram or whatever is needed to put that brand forward.

Robert Newman: One more thing I wanna say about MOTY. In the way we do the judging, it’s always been the only category that all the judges vote on. Most judging is compartmentalized, whether it’s SPD or any other place, where small groups of judges vote on different categories. But for MOTY, every judge, and it’s a really diverse group of people, gets to vote. So, I think it’s really representative of—like you were saying, Pat—it’s sort of where people are at. Like people respect this magazine this year and that’s the one they vote for.

Patrick Mitchell: But it’s interesting to think about the relevance of design in this world. You’re right, a small group of people are doing great work, but what does that say about the business? That creativity is not that important at most magazines?

Robert Newman: It’s a weird dynamic right now because there are magazines and publications, I think, that are doing the most brilliant work that’s ever been done or that they’ve ever done. I really feel strongly about that. For example, The New York Times across the board is just operating at such a brilliant level, from front to back, that no one has ever been at. It’s just such a brilliant fusion of edit, and visuals, and photos, and art and design. And then when you drill down to the Kids thing that Deb does, and the magazine, and the special sections that they do, and the awareness that they have. The special At Home section they did during the peak of the quarantine that sort of replaced the Travel section. I think it’s just genius.

And they’re not afraid to experiment. It’s just amazing. They’ve never, nobody's ever been at that level. And New York magazine has been operating at that level for years. And every time I look at it, I think, “Oh my God!” The stuff that Tom Alberty and Jody Quon are doing is just like, whoa. And they do it every—now it's every two weeks—but still, like over and over and over again. They’re redefining what they do. And at the same time, doing really provocative covers that lots of other people can’t do. It’s phenomenal. And The New Yorker too, I think, has been operating at that level. And some others, you know, like Bon Appétit. I think Michelle Outland is still there. I mean, just, whoa.

“There are magazines that are doing the most brilliant work that’s ever been done [right now]. The New York Times is just such a brilliant infusion of edit, and visuals, and photos, and art and design. It’s just genius.”

Debra Bishop: Yeah. She’s not there anymore, but yeah, she was amazing.

Robert Newman: I mean, just mind-boggling. And, I think he left, too—Emmett Smith at National Geographic—that magazine’s never looked better. There’s a lot of people doing really skillful work at a technical level I could never imagine doing. It’s very technically skilled, but they just don’t have, in many cases, they don’t have the palette. They just don’t have the runway to do what’s needed. And, by the way, they also don’t have the editors they need.

Debra Bishop: Yeah. I think a lot of it has to do with support. And support for print. It can’t just be “everybody’s moving to digital.” That’s clear, but let’s do what we can with what we have.

Robert Newman: Obviously, the magazines I mentioned, what distinguishes them is they have brilliant editors. They have editors who are giving the support and the inspiration. The other thing that’s missing now, unfortunately, is you don’t have those launches anymore. You just don’t have launches. I say this with a lot of respect, but the most exciting launch this year was the pickleball magazine that Jill Armus did. And that’s great. I mean, genius. She’s the best, but it used to be there would be like THIS magazine, and THAT magazine, and THIS magazine launching. Or somebody would do a whole rebrand, like we did at Details. Like you were talking about earlier—a whole revamp. That stuff just doesn’t happen anymore. And it’s not a criticism of the art directors because those art directors that are working at places like Fast Company or Good Housekeeping, they’re doing genius work. But they need editors and runway. You’ve got to have an environment. Magazines do not exist in the vacuum. They exist as an expression of the culture that they come out of. But they’re just a business now. They’re just trying to make money and survive.

Debra Bishop: Yeah. I think that a lot of the digital products you end up in like a website or even an app, there’s this push to make us all just “box fillers. Just fill that box.” And that’s it. I don’t feel like I’ve been working in that kind of environment or been working that way. I’m thinking about much more than just what goes in the box.

Robert Newman: This is the challenge that we were talking about earlier. How do you get young people into this field when there are obvious limitations? And another limitation is the entry-level jobs just aren’t there anymore. I don't know how you guys started out, but I didn't start out art directing Entertainment Weekly. I moved up the ladder, and so many people I know started out in production. I mean, Wyatt Mitchell, who you guys know, he became the creative director of The New Yorker. He worked with me as a production guy at Details. You know, you had all those entry-level jobs so people could get in and learn the trade. The craft. Those jobs don’t exist anymore. There’s no more production department. There’s no imaging department. There’s no more copy department for editors.

That’s why you have the editor problem. You used to have half a dozen junior editors who were all really smart and competing against each other. They’re not there anymore. You don’t have that entry-level thing. And just to extend that, you don’t have those—like you guys, you both worked at music magazines, I did too—places where you could start out and have a lot of freedom. Musician magazine, Pat, how many people came through there? [John] Korpics, and you …

Patrick Mitchell: David Carson…

Robert Newman: Dave Carson, Gary Koepke. Those magazines don’t exist anymore. The altweeklies that I came out of. They don’t exist anymore.

Debra Bishop: That sort of artistic outlet for typography and conceptual art doesn’t really exist. It’s a different world.

A sampling of miscellaneous Newman projects.

Debra Bishop: Bob, you’ve been at this a long time. How have our jobs as art directors, creative directors, design directors—because the landscape has changed so much—have the rules changed? Is it a different job?

Robert Newman: I think it’s interesting because I’ve been at it longer than both of you, but you’ve been at it long enough to see. I think our jobs got much better and we got a lot more respect and a lot more responsibility and a lot more “control” for lack of a better word. When I started out, art directors were just page decorators. They were just supposed to make everything look pretty. And fit. They certainly weren’t supposed to have impact on the content. In any way.

Patrick Mitchell: We weren’t partners.

Robert Newman: Yeah. No. And that definitely changed. I don’t exactly know all the reasons why, but partly because of desktop publishing and partly because I think the skill level of art directors and design directors—we just were much better at what we did. And people had to recognize that we knew what we were doing, and we could take their magazines to a place that they couldn’t without us. And it used to be that you could have a butt-ugly magazine and they were making money hand-over-fist. Like newspapers. It didn’t matter. The magazine could be the most butt-ugly thing in the world. And they made a fortune. Then you couldn’t do that. You had to have a good-looking magazine. And things like Rolling Stone, and Entertainment Weekly, and Fast Company, they changed that dynamic. You had to have a talented art director, a design director. And you had to work with them.

I also think generationally, editors have changed. You got editors who were much more visually-oriented. So that was good. Our job changed for the better until, you know, magazines started the Great Crash and everything a few years ago. And now I feel like, in many cases, we’re just holding the pieces together. And I think in many cases we have a certain institutional memory, so we know what magazines are supposed to be and how they're supposed to work. And younger editors need that from us. So that’s good.

Debra Bishop: If they’re willing to.

Robert Newman: If they’re willing to. But that’s something a lot of young editors coming up don’t have. They don’t have that kind of knowledge and that sense of visual storytelling. So there’s still a role for us, but I think it’s much more about production and managing, and much less about creatively expanding the definition of what a magazine is and can do.

“Where magazines were essential, is that they reached out to you directly. [Growing up], I’d find a magazine and it was my connection to another world. You’d read it and pass it around to your friends. And those indie magazines don’t have that. They’re just objects of art that look pretty. They’re not editorial design. They’re not real.”

Debra Bishop: I had a question about something that I think about a lot, which is we’ve seen some very old brands over the years, a hundred years, you know, talking about Vanity Fair, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, The New Yorker. I don’t know how old it is, but The New Yorker’s doing quite well moving into the digital age and holding on to its branding, but there are some really big brands that you think about looking at them on the phone, and you know that they’re just not gonna be able to make that leap out of print into digital. And I’m just wondering what your thoughts on that are.

Robert Newman: You know, magazines have runs, and they’re not destined to last forever. They have good runs. I’m gonna make an analogy here that I think you guys will get. Magazines are essentially like rock ‘n’ roll music. They’re like rock bands. And they have runs, and they put out a bunch of good albums, and they’re really popular. And then they get old. And many of them just go away because their time has come and gone. And a lot of that is because, like I said before, magazines don’t exist in a vacuum. They’re responses to cultural moments. Real Simple or Martha Stewart Living didn’t come out of the ether and become magical. They were responses to where women’s heads were at at the time. And they connected in such a brilliant way, and they were successful.

Same with Entertainment Weekly—which now, by the way, is a monthly—which says all you need to say about magazines [laughs]. But like rock music—rock music used to be an essential thing for our lives. We lived and died for rock music. You couldn’t wait until the next album or whatever came out. But rock music is not urgent anymore. It’s not essential. Its time has come and gone. I’m not talking about pop music, or R&B, or hip-hop. Just rock and roll music. Its just not a really dynamic force that moves the culture anymore. And neither do magazines. We have to accept that fact. There’s a new paradigm, and I don’t know what it is.

Debra Bishop: I think a lot of it has to do with trend, but I’m wondering if there’s, you know, a big brand like Time or National Geographic—how do they move into the digital age and slowly let go of print? It seems to me that there might be a way—and maybe that’s a bad example because they’re probably doing okay with that, but I just feel like there’s some short-sightedness in terms of that switch over to the digital platform. It should be doable, but does it have to do with a shrinking visual?

Robert Newman: National Geographic is not a good example. They’re so attuned to the modern era because they do TV. That’s what they do. And video. I think The New Yorker and New York magazine, and The New York Times for that matter—those are the places to look at how storied brands, where the print is still essential to their DNA and to their reader’s identification, how they move. And in The New Yorker’s case, which is probably a good one because I don’t know about you guys, but I don’t pay that much attention to their digital side, but with them, it’s been a matter of diversifying and coming up with The New Yorker Festivals and The Cartoon Bank—which they made a fortune off of— and sort of figuring out ways to leverage their brand.

And also, they’re really drilling down and identifying their readers and jacking up the cost of the subscription. It’s really expensive. The New Yorker’s really expensive. And New York magazine has just brilliantly fused the digital with the magazine. But they don’t try to do the magazine. Their digital presence is not a replication of the magazine. It’s just digital. And the Times is the same way. Sometimes I’ll read a story in the Times and I won’t even remember that I’ve read it online, too. It looks so different. I’ll read something in the Sunday Times. And it’s like, “Oh, wait a minute. I forgot. I read this three days ago online.” Because what they don’t try to do is this whole replication thing that we all fell for.

Debra Bishop: Like with the iPad apps…

Robert Newman: That stuff was such a big mistake.

Debra Bishop: You have to leverage what you’re good at.

Robert Newman: The print magazines, the print magazine.

Debra Bishop: Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: This is the inquiry that launched this podcast for me, but it’s kind of a meandering question. So bear with me, I’m still trying to figure out what this question is, but along the lines of what Deb was asking, when print is dead, where can a magazine maker take these unique format-specific skills? Magazines were the product of editors, designers, photographers, illustrators, typographers, and writers, working together to combine their skills to make these beautiful objects—and they really were beautiful objects—and they did it on a schedule. And these objects had a life. Individually, and as part of an ongoing relationship with their audiences. There’s really nothing else like them. And you could say that a lot of these indie magazines that are popping up kind of preserve that spirit, but on the larger scale that was big magazine publishing companies. I don’t really see an outlet for those kind of skills to be applied. Do you?

Robert Newman: I think there are a lot of companies and a lot of brands that are scooping up magazine people to work on what they think is stuff that magazine people can do, and a lot of it is branding. And a lot of it is native stuff. You know, the Times does a lot of that and everybody does a lot of that. I don’t have a lot of interest in that, but I think there’s room there for people to do work—and do good work. I see it at the Times. A lot of the native stuff is pretty interesting and creative.

Patrick Mitchell: But you know, we’re talking about, outside of media, where companies and brands are scooping up that talent. What they’re trying to do is establish the kind of relationship that magazines had with their audiences and build an audience like that. Of course, it’s debatable if they can actually do that.

Robert Newman: Of course. Apple hired all those magazine art directors because they wanted to make magic with Apple News. Well, you guys, I don't know how much time you spend with Apple News, but I don’t think it takes the genius level of the people we all know who’ve been hired by Apple to do that stuff. I just don’t.

Debra Bishop: Absolutely. But is that what they’re doing over there? I never know what they’re doing at Apple.

Robert Newman: Well, whatever they do, I support them and I encourage everybody who can get a gig over there to get a gig. Go for it. Because it’s good. And they’re not doing anything bad.

I don’t know. I don’t think magazines are going away. I think that the challenge is how can all of us and new people coming up, make magazines be better and be more dynamic. And, to go back to my rock ‘n’ roll analogy, I don’t think there are a lot of magical new rock ‘n’ roll bands coming up. There are not a lot of Pearl Jams or Jimmy Hendrix’s or whatever your linear point of references are. But some of the best rock shows I’ve seen in my life are shows that I saw done by people in their 60s and 70s. I mean, just magnificent stuff. And I think that’s the level that we, as magazine people, have to strive for. Like people have these chops to die for. They’re just chops forever. And you’ve just got to get in a situation where you can use those chops and find your audience—and the audience is not gonna be big. We’re not going to be selling 400,000 copies on the newsstand. We sold that at Real Simple. Or 200,000, like we sold at Vibe. Those days are gone. But you can still impact an audience. And it’s probably not going to be a young audience. That’s the key. It’s just not gonna happen. It’s not there.

It’s gonna have to be an older group, just like when you go to a rock music gig. The joke about rock music now is there’s a bigger line at the men’s room than at the women’s room because it’s all these guys who have to pee every 30 minutes. I went to see Brian Wilson and people were dying. The women were all like, “We’ve never seen this before.” But you have to have that connection with a community and you have to be essential to a community. And you have to be in a place where you’re dictating a conversation to people. But where magazines worked, where they were essential, is that they reached out to you directly. I don’t know where you guys grew up, but where I grew up, I would find a magazine and it was my life connection to another world. Like The Village Voice, or Ramparts, which I adored. You’d find a magazine. You’d read it and pass it around to your friends. It was like passing around a 45 record that you’d just got. It’s like when punk came out and we’d pass around these little 45s.

The magazine was your life blood and your connection. And that’s what those indie magazines don’t have because they’re just like coffee table books that are supposed to look good on your—I mean, really, they’re just objects of art that look pretty. They’re just decoration. They’re not editorial design. They’re not real.

Patrick Mitchell: A lot of them are missing that sort of urgent content.

Robert Newman: The thing about magazines is no matter what magazine you ever worked on, your goal was to reach as many people as possible and be a success. It didn’t matter whether you’re working at Musician or Vibe or Rolling Stone or The Village Voice—you wanted it to blow up, right? You wanted it to blow up. And when people heard you work there, they’d go like, “Oh my God.” Like when I worked at Vibe, man, when people heard I worked at Vibe, they would just like flip out. It was like magic. You know. You guys worked at magazines like that.

Debra Bishop: Martha Stewart was certainly that way. Exactly. Right. And in the early days, Rolling Stone was, you know, wonderful.

Robert Newman: I’m embarrassed to say that the magazine I got the most shine from was Real Simple. Like, oh my God. [Laughs]. People love that magazine.

Debra Bishop: It has a cult following. Yeah. Bob, how do you want to be remembered? How do you, how do you think people will remember your work?

Robert Newman: What I’m most proud of is where I gave people a chance to do their best work. Illustrators and photographers and designers who worked for me where, you know, they could just come in and do amazing things. And whether they were young illustrators or young photographers or older for that matter. I think that’s what I’m most proud of. Giving people a chance and giving them a voice.

And sometimes they were people that like—you guys know how it was back in the day. And it’s still that way—people of color or women or gay people or whatever, you know, they couldn’t get a break. And whenever you could give anybody like that a break. Or even just somebody who was “weird.” We all knew that person who was weird and you gave him or her a break and it's like, you know, they became a star. To me that’s great. I mean, that’s the legacy that we would all strive for. I think magazines in general are so temporal.

Maybe some day, some kid will look at some magazine I did and go, “Oh really? How did they do that?”

You know? [Laughs].

For more information, visit Newman’s website, Newmanology.