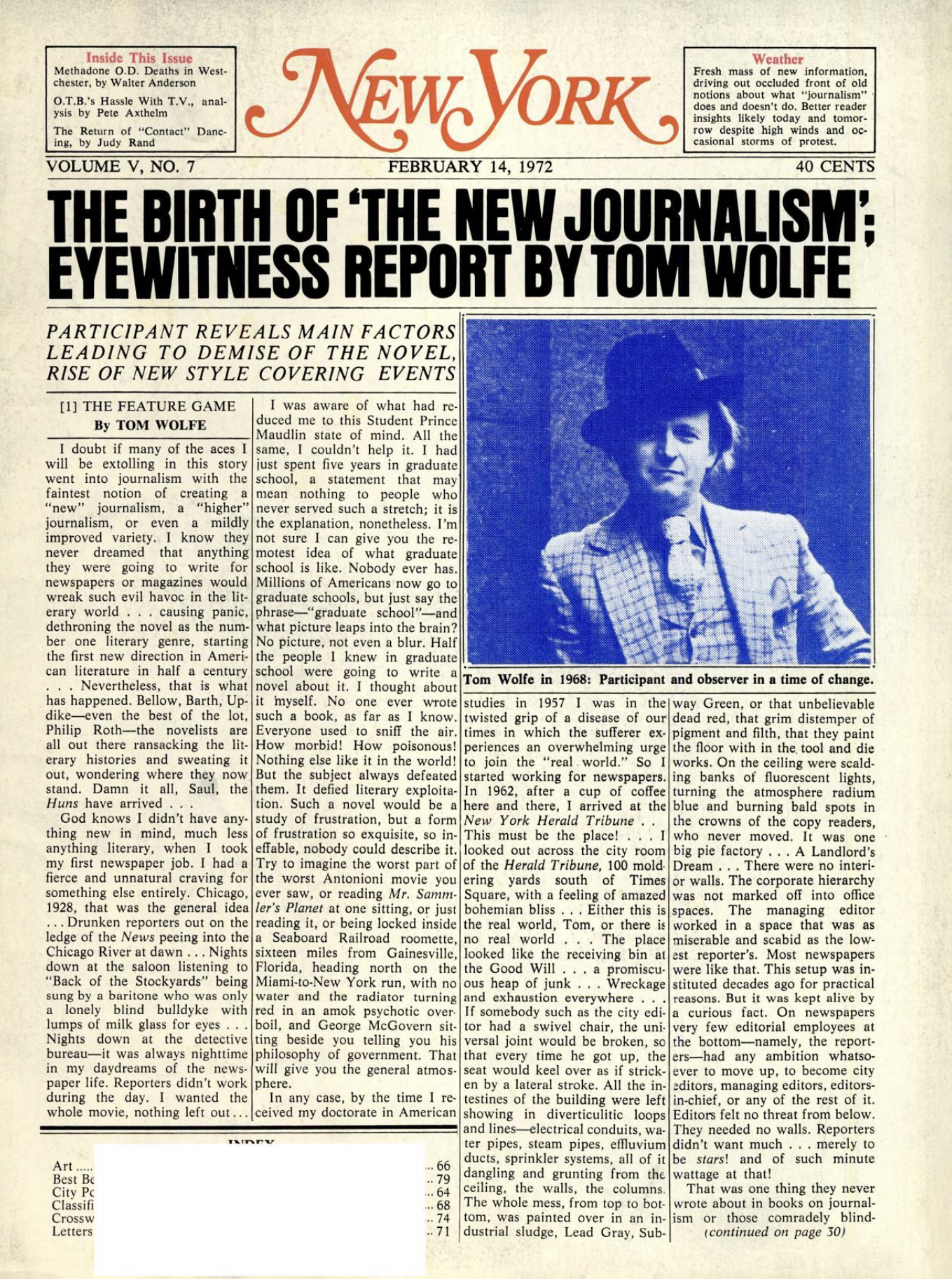

Design, Build, Modify

A conversation with designer and editor Scott Dadich (Texas Monthly, Wired, more)

A conversation with designer and editor Scott Dadich (GDP, Wired, Texas Monthly)

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT MOUNTAIN GAZETTE, COMMERCIAL TYPE, AND LANE PRESS

In his mid-20s, Scott Dadich told his editor at Texas Monthly, Evan Smith, that he wanted his job.

A move like that is a combination of arrogance, youth, and frankly, balls. But you should also know that Dadich is an engineer. And what do engineers do? Well, according to one definition in Merriam-Webster, they “skillfully or artfully arrange for an event or situation to occur.”

Of course, you probably know Dadich as an art director and editor, but beyond the titles, he’s the kind of guy who builds things, re-engineers them, re-configures them or, more importantly, thinks differently about them.

To date, his life’s work has been building magazines—marrying words and pictures and combining his love of math and engineering with an eye towards new, unforeseen outcomes in a long career that includes stints at the aforementioned Texas Monthly, and also Wired, Condé Nast Digital—yes, we’ll talk iPads—Wired (again) and then on to his own agency, Godfrey Dadich Partners, where he is trying to engineer a new approach to advertising.

As a rare creative who has helmed a magazine as an editor-in-chief and art director, Dadich has ideas about how to better create everything, from where digital and print sit in the ecosystem, to the makeup of an actual magazine, and even how teams should fit on the masthead. He has put these ideas to practice on the page, on the web, and also on the streams, in his award-winning Netflix series about the creative process Abstract: The Art of Design, which premiered in 2017.

Our conversation with Scott, a rather long one for us, starts right now.

“Leaders who are pioneering the future have an obligation to tell their own story and to do so truthfully.”

Scott Dadich: Are you guys having fun? It’s just such a joy to have this podcast. Let me just say thank you.

Patrick Mitchell: We are having fun, yeah. And thank you. So I’d like to start by asking you about Mookie Sullivan, your fashion brand. Your tie company.

Scott Dadich: Oh, yeah. Wow.

Patrick Mitchell: There’s still a Facebook page for Mookie. But, yeah, what was that all about?

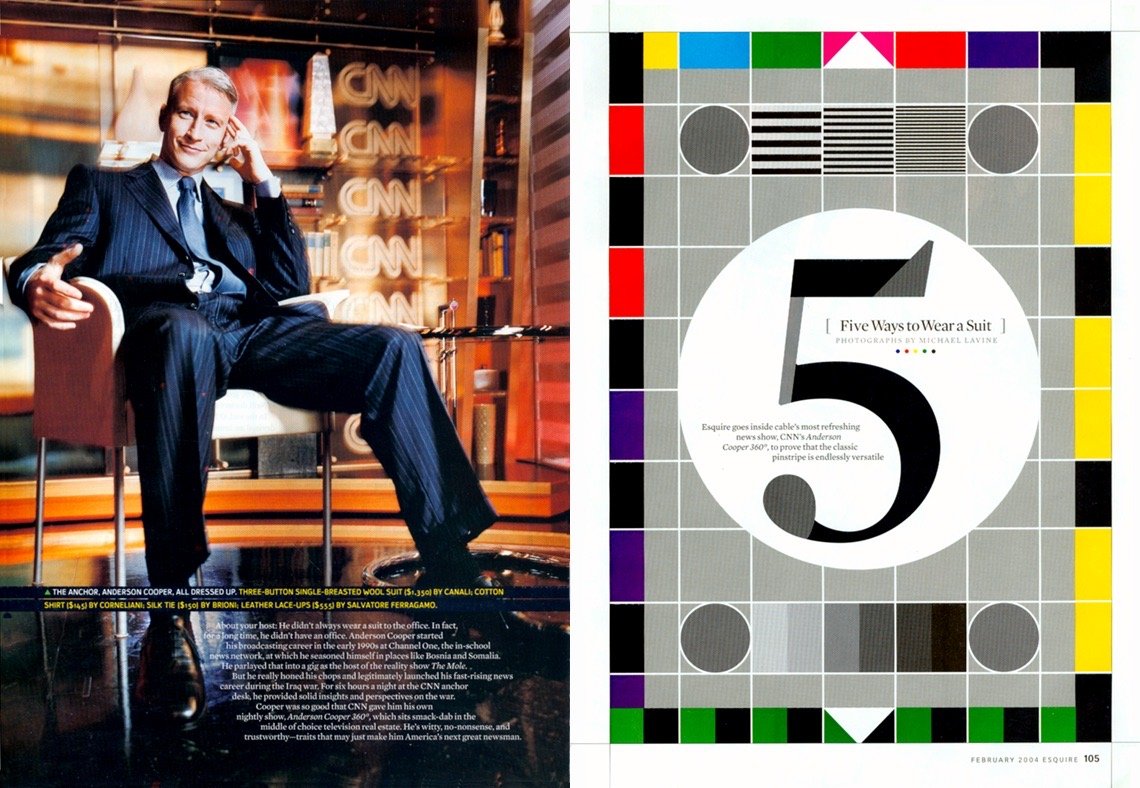

Scott Dadich: That was fun. So Mookie was a product of working and living in New York for the first time. I had started to work at Condé Nast corporate at the moment. But I had a big affection for men’s fashion. Wyatt Mitchell really infected me. Like when Wyatt came to work with me at Wired, he brought the sort of “suiting culture” to Wired.

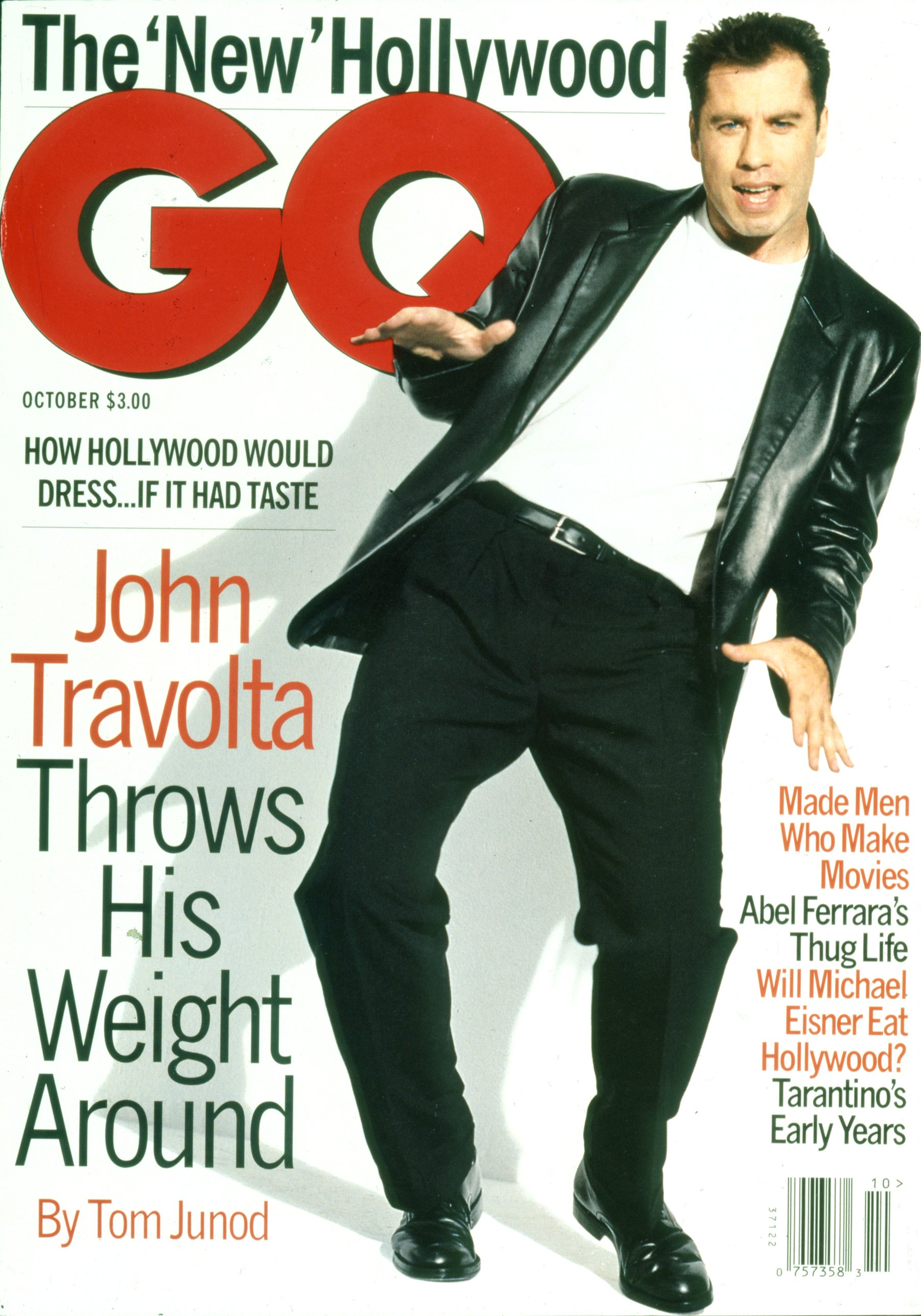

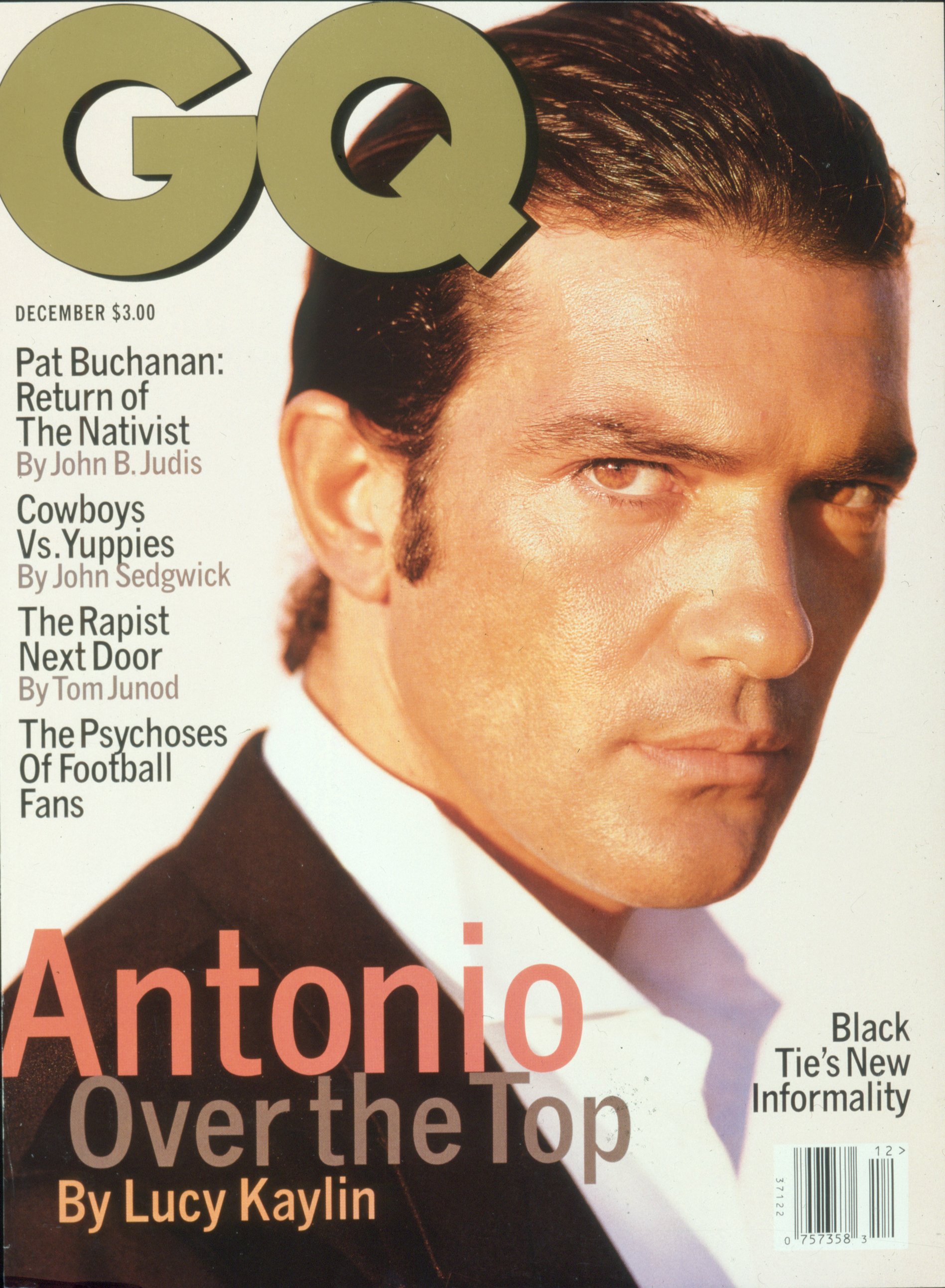

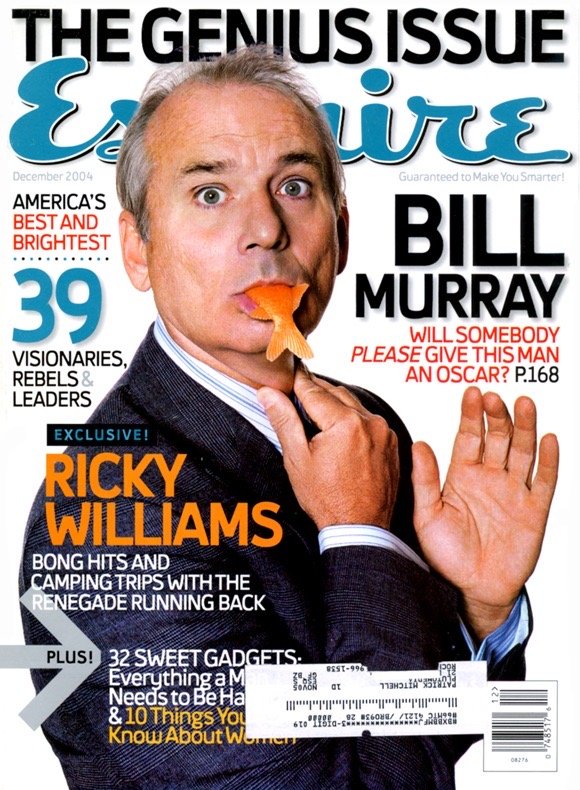

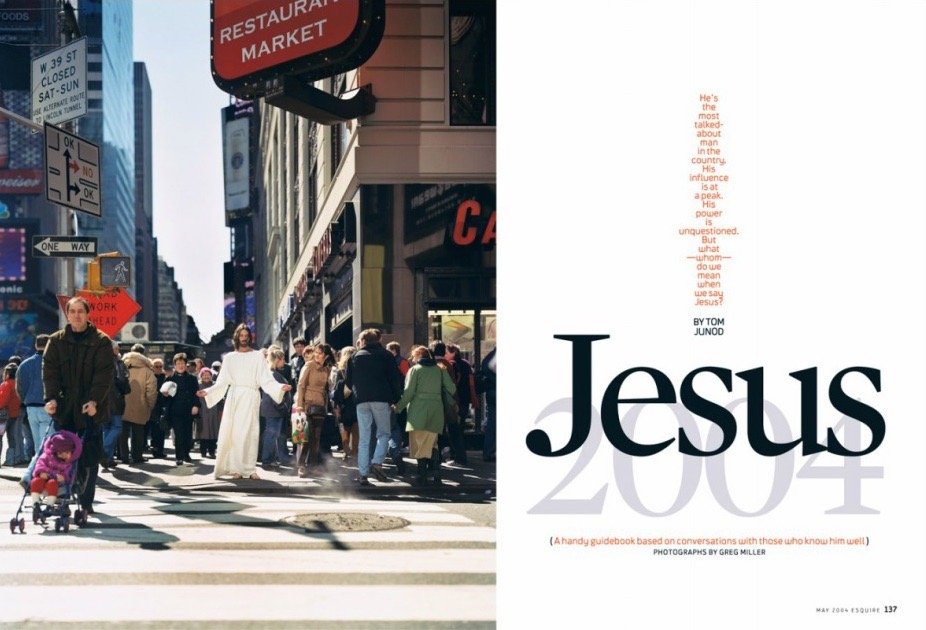

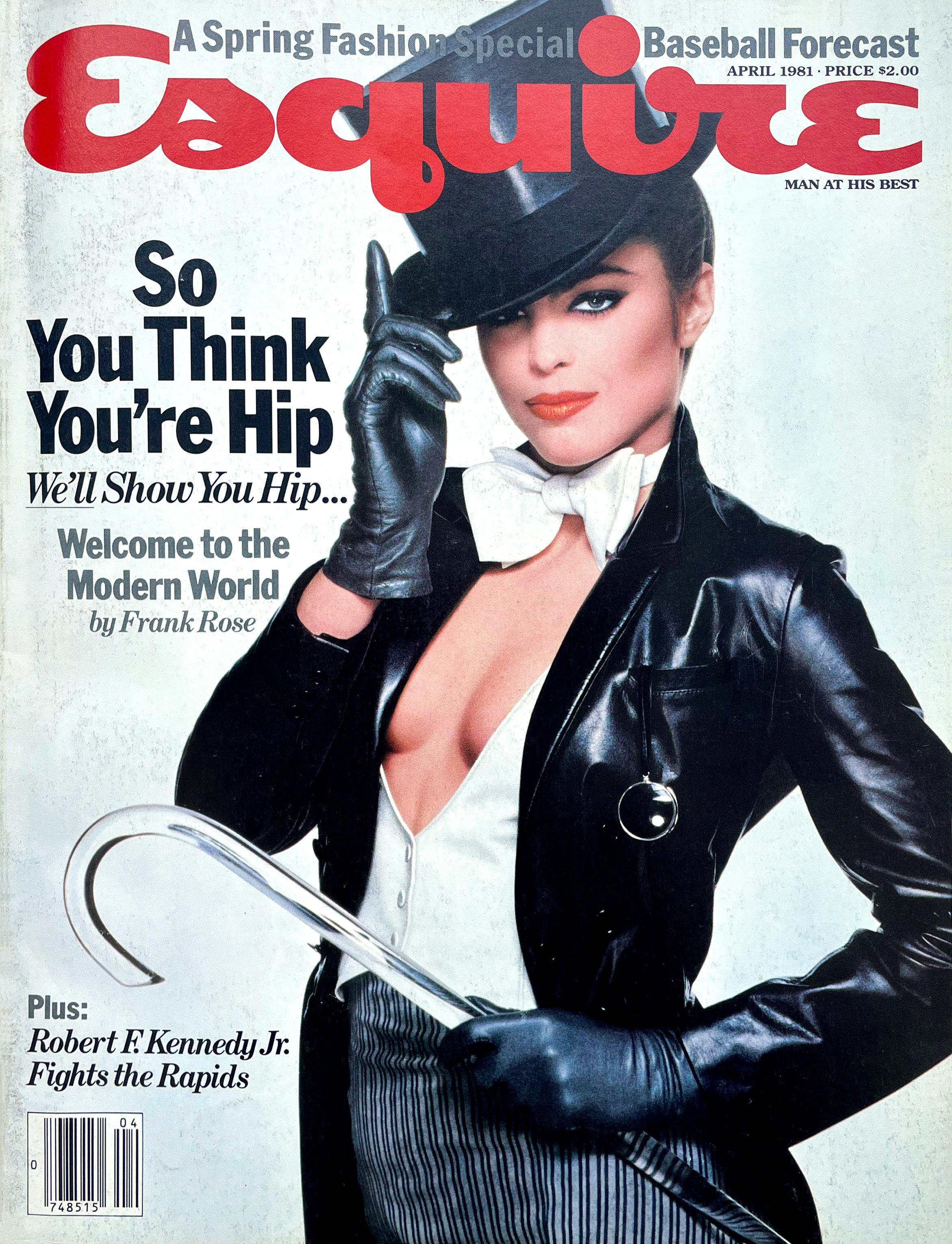

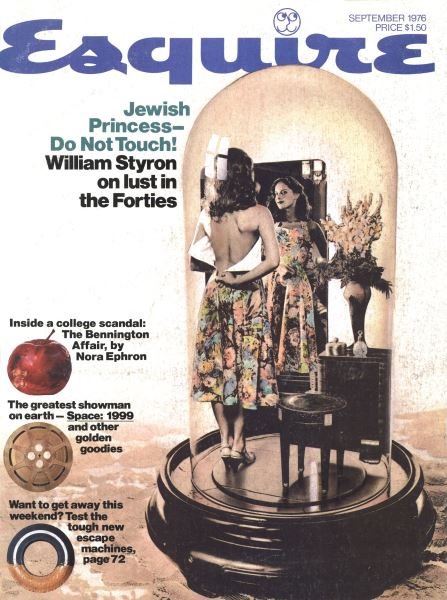

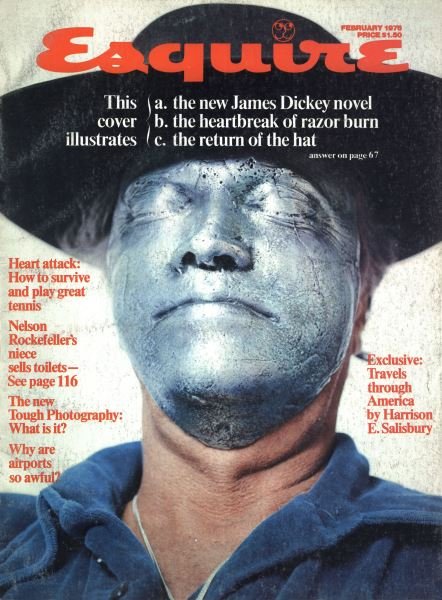

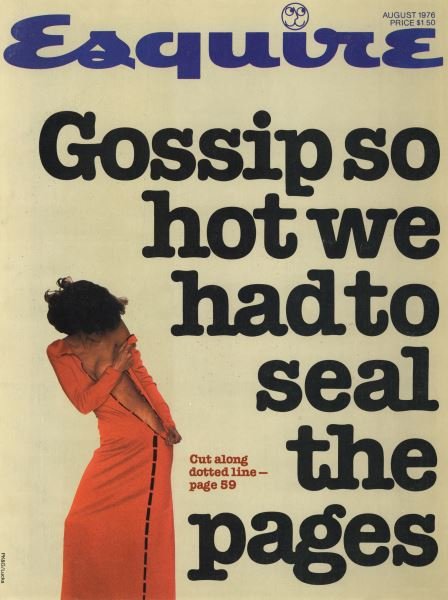

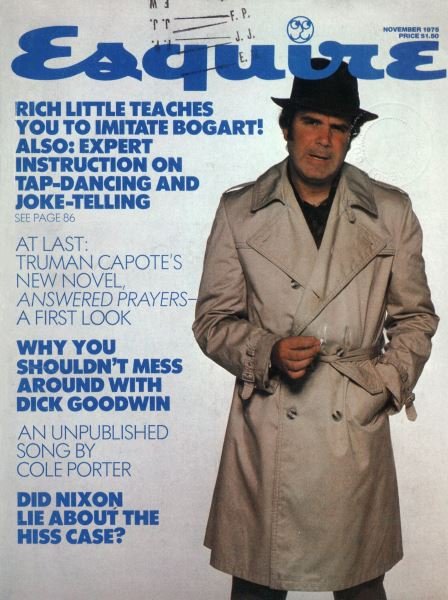

Wired was not a place where you would dress up in a suit and tie. But Wyatt really taught me the fine art of haberdashery. And also just being a reader of Esquire and GQ over the years, there was definitely a movement where ties became a thing. And I think it was a combination of that, plus graphic design, plus Wrong Theory that I felt like I had something to add into a sartorial context when it came to ties.

And that was confirmed as I became a full-fledged Condé Nast New York employee and it was a whole thing to dress up every day. And so I wanted, it’s really a statement piece that would be at the center of your person and found that I just loved designing the ties. And I had a couple of friends who helped me pull together the manufacturing on it.

And it was actually turning into a thing that we’re getting retail distribution and starting to sell them. And funny enough, then Hurricane Sandy hit. And right after that, I got the offer to go back to Wired as editor-in-chief. And so we put Mookie on the shelf and it never turned into anything. But it was fun. It was a fun hobby.

Patrick Mitchell: Do you still have the full collection?

Scott Dadich: They’re actually hanging in my closet now. And I do dust them off from time to time. It was a moment in time. I’m glad that was not more than what it was, but it was awfully fun to play with.

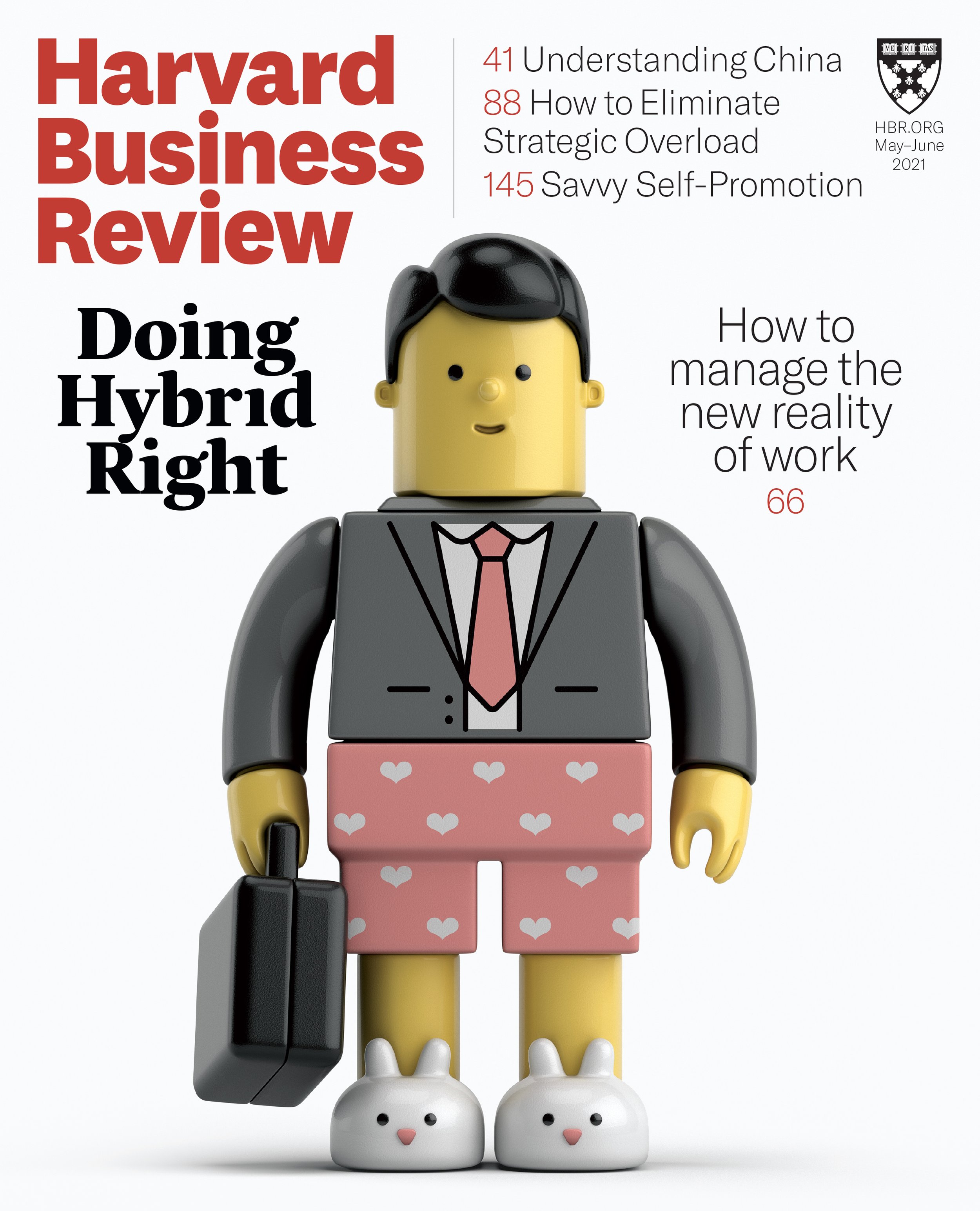

Patrick Mitchell: Alright, we’ve got a lot to cover, and we’re going to jump around, but I think one of the more interesting, hopeful places that I’d like to start is with your slogan at GDP, “The New Editorial.” And listeners, you can actually go to the website, theneweditorial.com, to read more about it. But for people in our business, this is really an inspiring thing. So can you talk about what The New Editorial is?

Scott Dadich: Yeah, this has been a thesis that’s been kicking around for years. It's funny now to reflect—in my eighth year of GDP that doesn’t feel so new anymore. But I guess the premise of it is one that centers on using the magazine toolkit, using the modern magazine tools to help organizations and brands and movements tell their story.

And that living through the challenges that we all have in the magazine world, and the business pressures, and larger business context that has existed around and suppressed the growth of magazines, and newspapers, and journalism, and editorial at large, that there is a new and fledgling movement among those in the know, and those who are those leaders who are pioneering the future, who are inventing the future that they have an obligation, even a responsibility, to tell their own story and to do so truthfully and in ways that are really dynamic and connect with audiences and stakeholders in really interesting ways, whether that’s a podcast or a video or a speech a CEO gives, but those tools are all really important and actually really germane to the communications landscape that we find ourselves in today.

Patrick Mitchell: It’s interesting because the reason I started this was not necessarily out of a concern for what’s going to happen to magazines, but it was more out of concern for where do people like us go in order to use the many skills, and talents, and resources at our disposal to make the, sort of, fully-fleshed out productions that we make? Because those can’t be applied, necessarily, on the web. And in a way, what you’ve done is you’re doing the exact same thing you’ve always done. You’ve just freed yourself from the confines of 108 pages, plus four covers.

Scott Dadich: That’s beautifully said Patrick. That’s entirely the premise.

Patrick Mitchell: And how have clients responded to that for whom this may be a real jarring kind of approach?

Scott Dadich: It’s been a real journey. We had some really quick and early success where we partnered with some leaders, especially in the space of technology and there was a real ambition and the Wired heritage was appealing to those clients.

But I think over the years, what we’ve come to understand, it takes more than just an appeal. It takes a really entrepreneurial, visionary, transformationalist kind of client or executive to drive the full value from the new editorial.

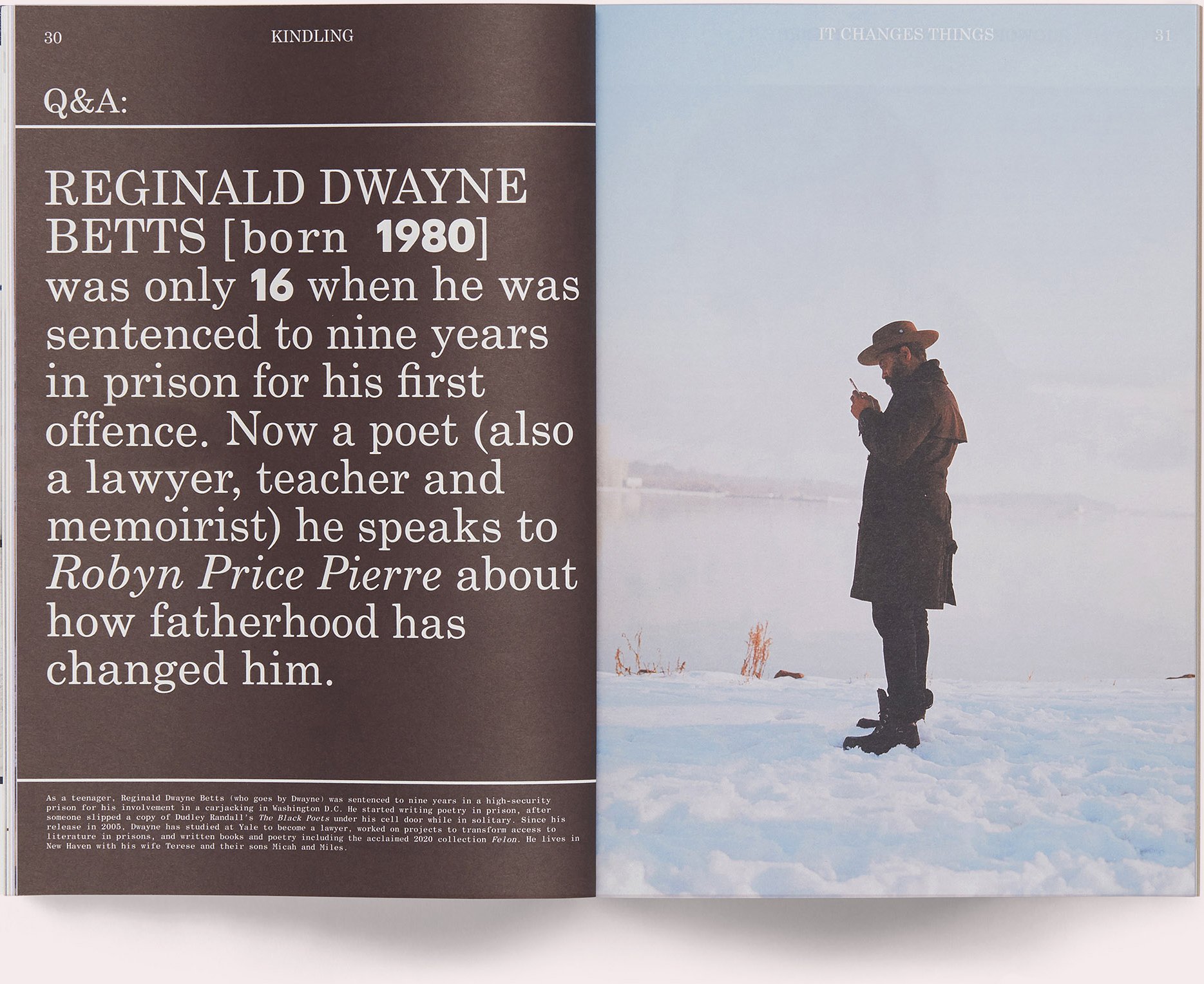

When you think about a spectrum and on the other side, there’s the cautious adopter—this is a COO, a CMO, a CEO who knows that what they’ve been doing in their communications portfolio might have shifted over the years, or mix of tactics, whether they were paid in an advertising context or PR, may be less effective given the fact there are just a lot fewer publications, newsrooms, places to get that story out through paid channels.

And so they have been seeking alternate methods and seeking new tools and tactics—whether they have to reach potential employees or stakeholders or shareholders or customers—there are needs to get those stories in front of a really diverse group of people and audiences. And it’s been those leaders who really get the bigger picture and who understand the bigger mix and the sort of business drivers behind it versus I just don’t want to run an ad campaign. I want to replace my PR budget with X, Y, or Z.

Patrick Mitchell: It didn’t hurt, though, that the advertising and marketing businesses had just completely lost their way and left a whole wide open for you.

Scott Dadich: Completely. There is a lane. There’s definitely a lane. But it does require new ways of thinking, new processes. I find when we’re in a challenging engagement, there are antibodies that come out of the partner organization to either attack the process or—even when I say we use the tools of journalism, we really do. We require that we get in and our reporters and editors can actually go into the organization and find the truth and uncover it and bring it up and lift it out into a storytelling format.

The clients sometimes forget that they’re on the hook to be able to produce those facts and show the truth. Sometimes it’s challenging and sometimes we have to reveal that they stumbled and that they fell down. And it is the act of dusting themselves off and pulling themselves together to create that progress. And that’s what we root for as audience members.

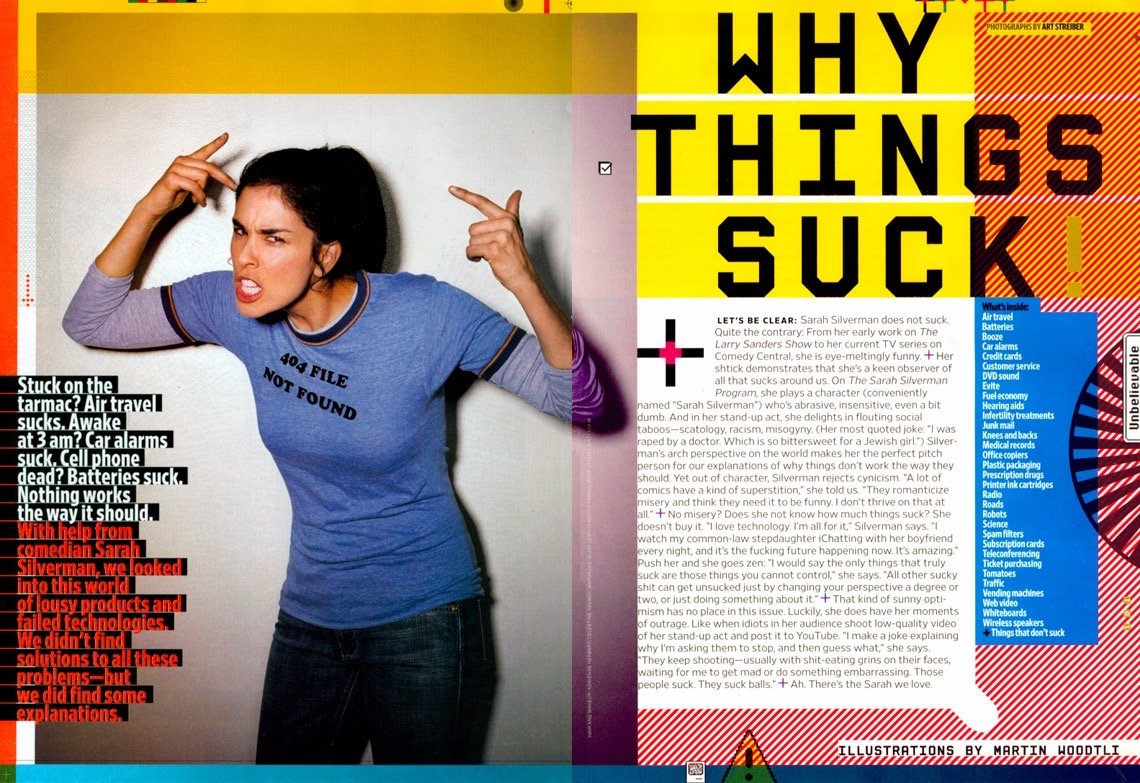

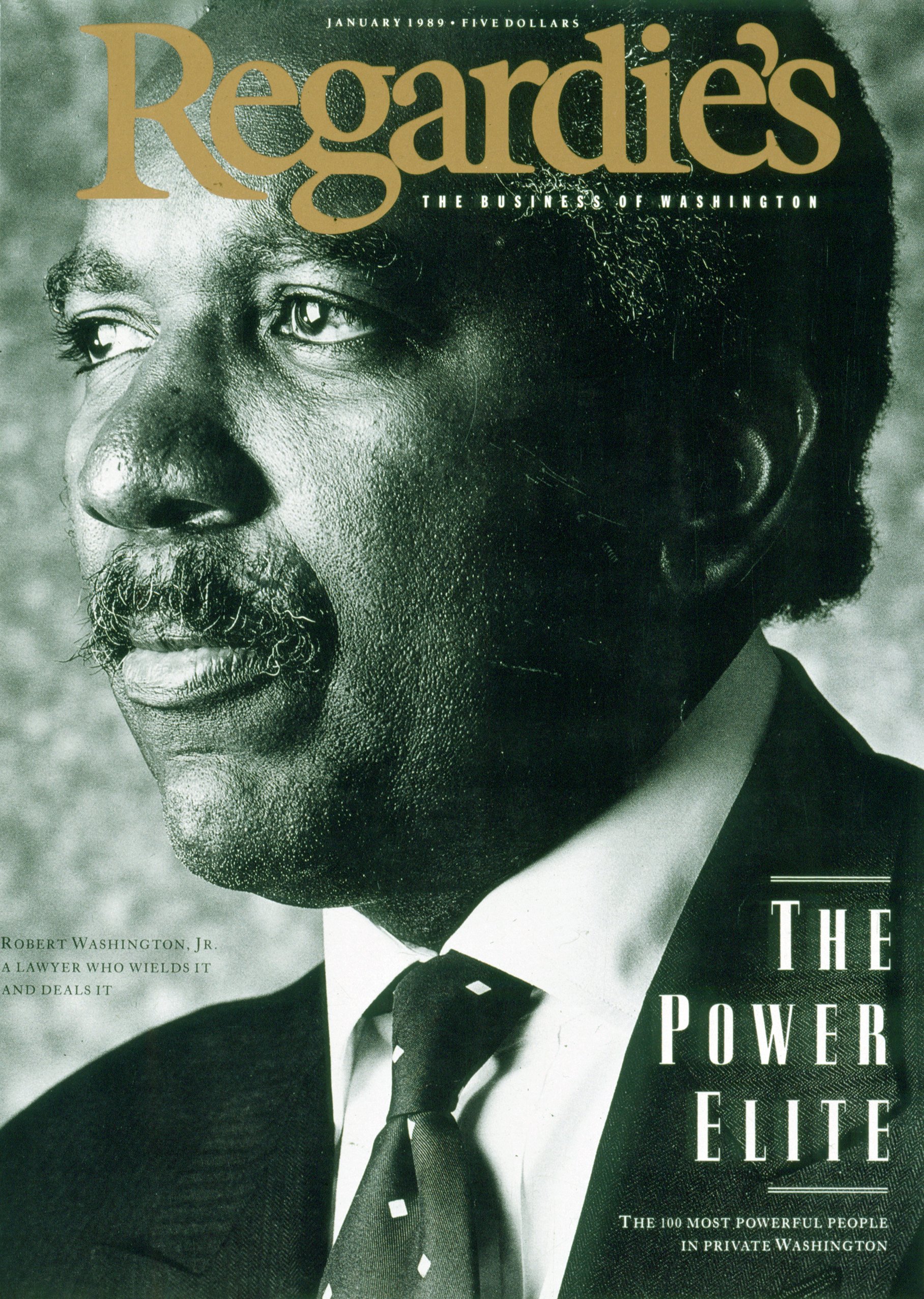

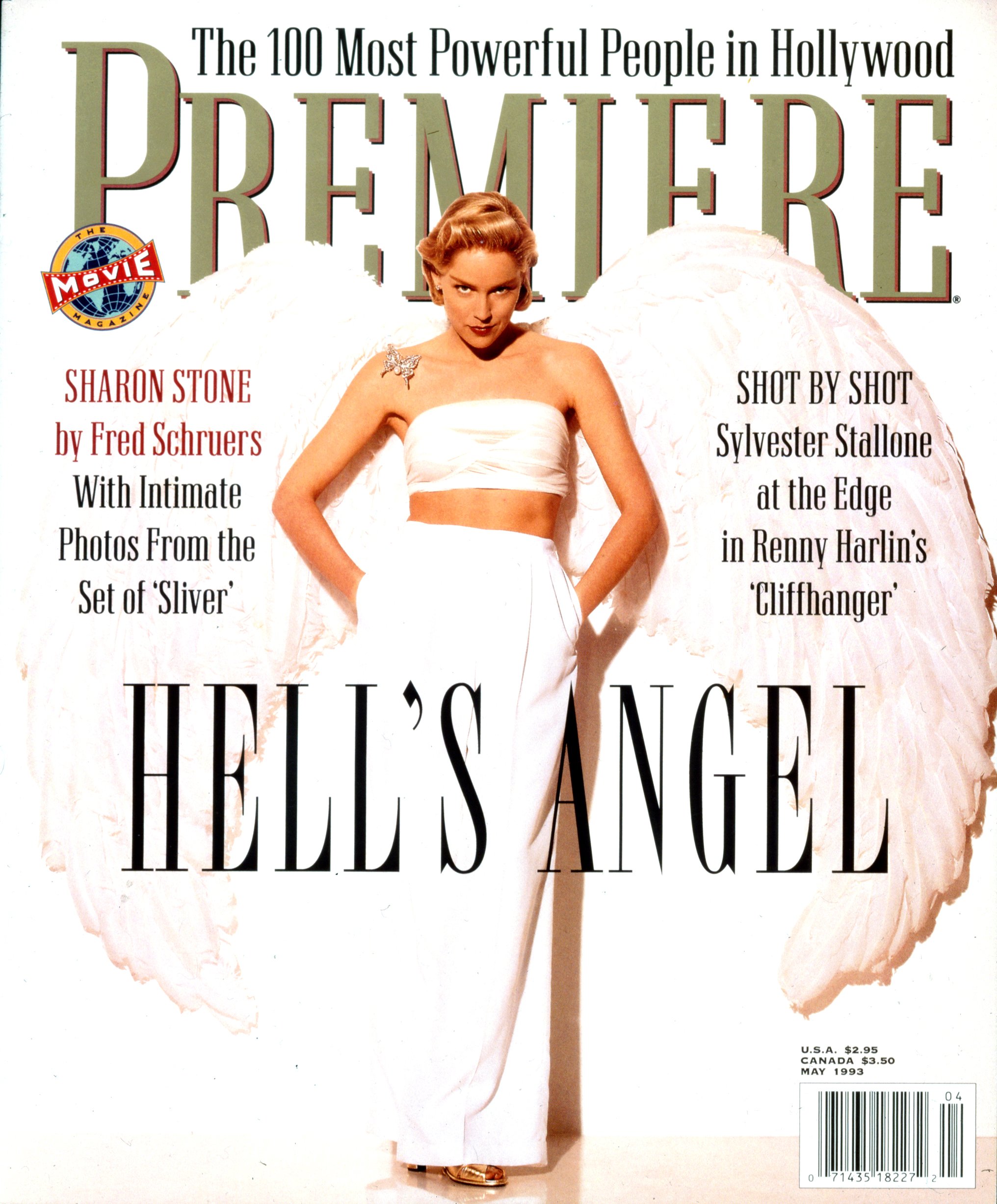

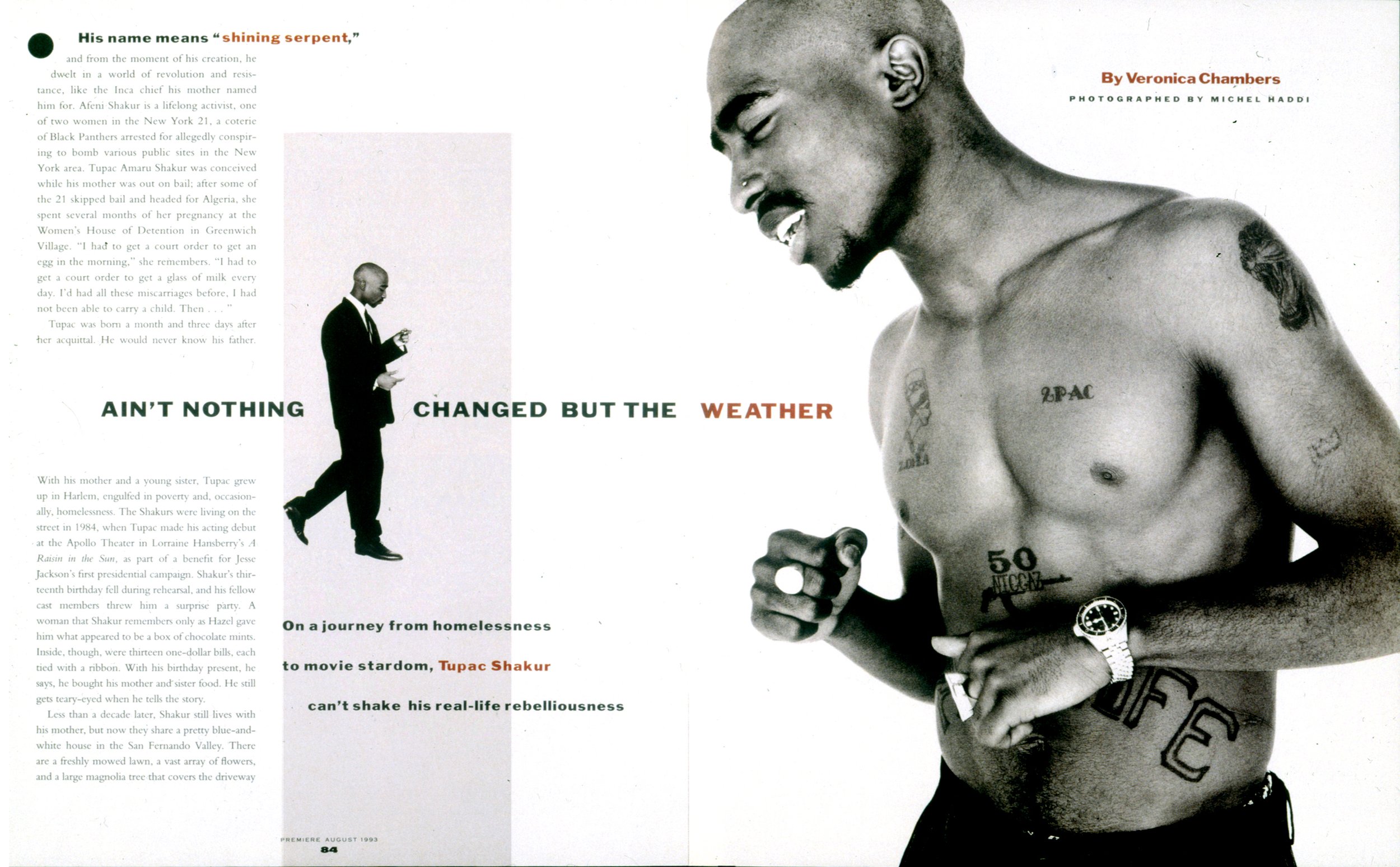

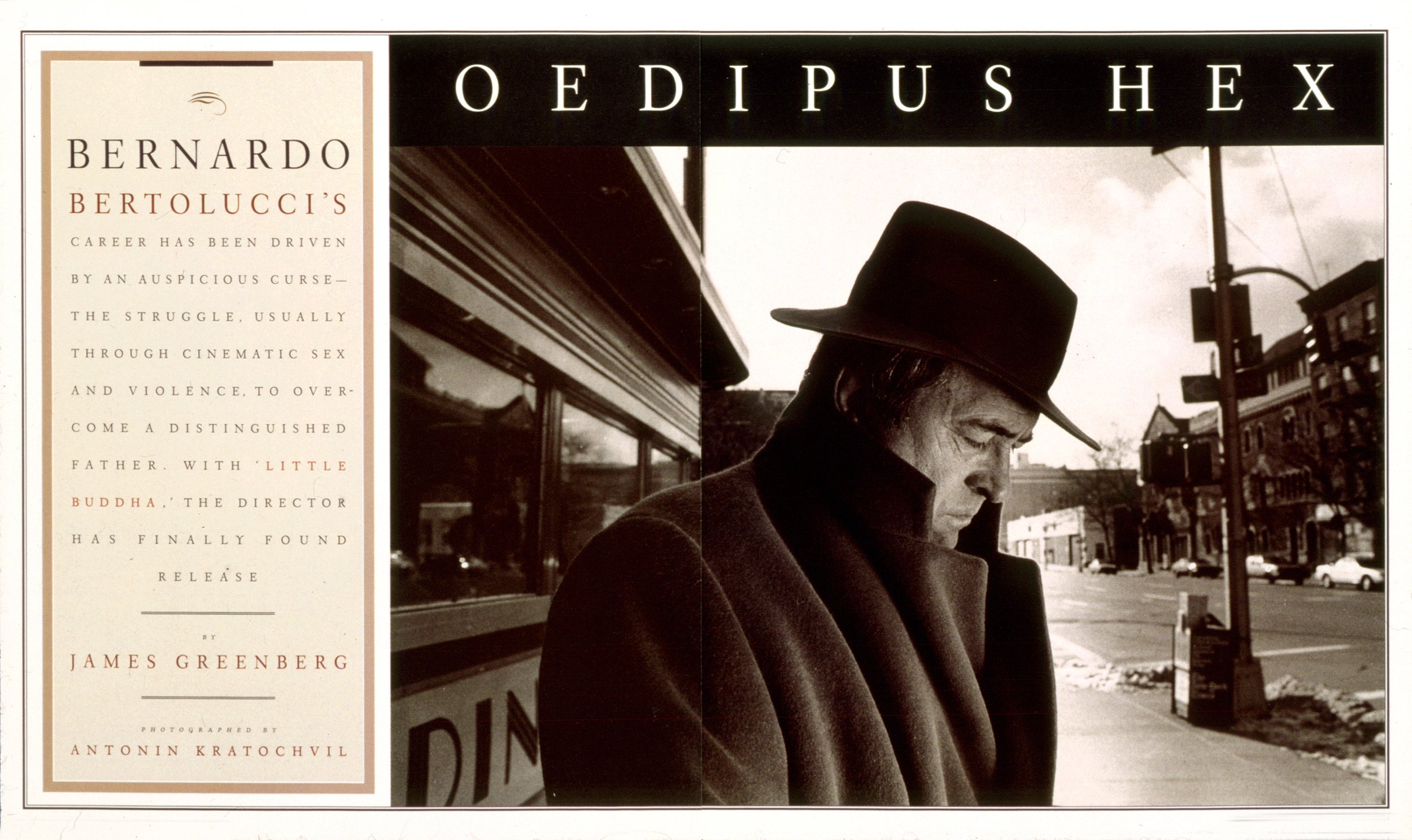

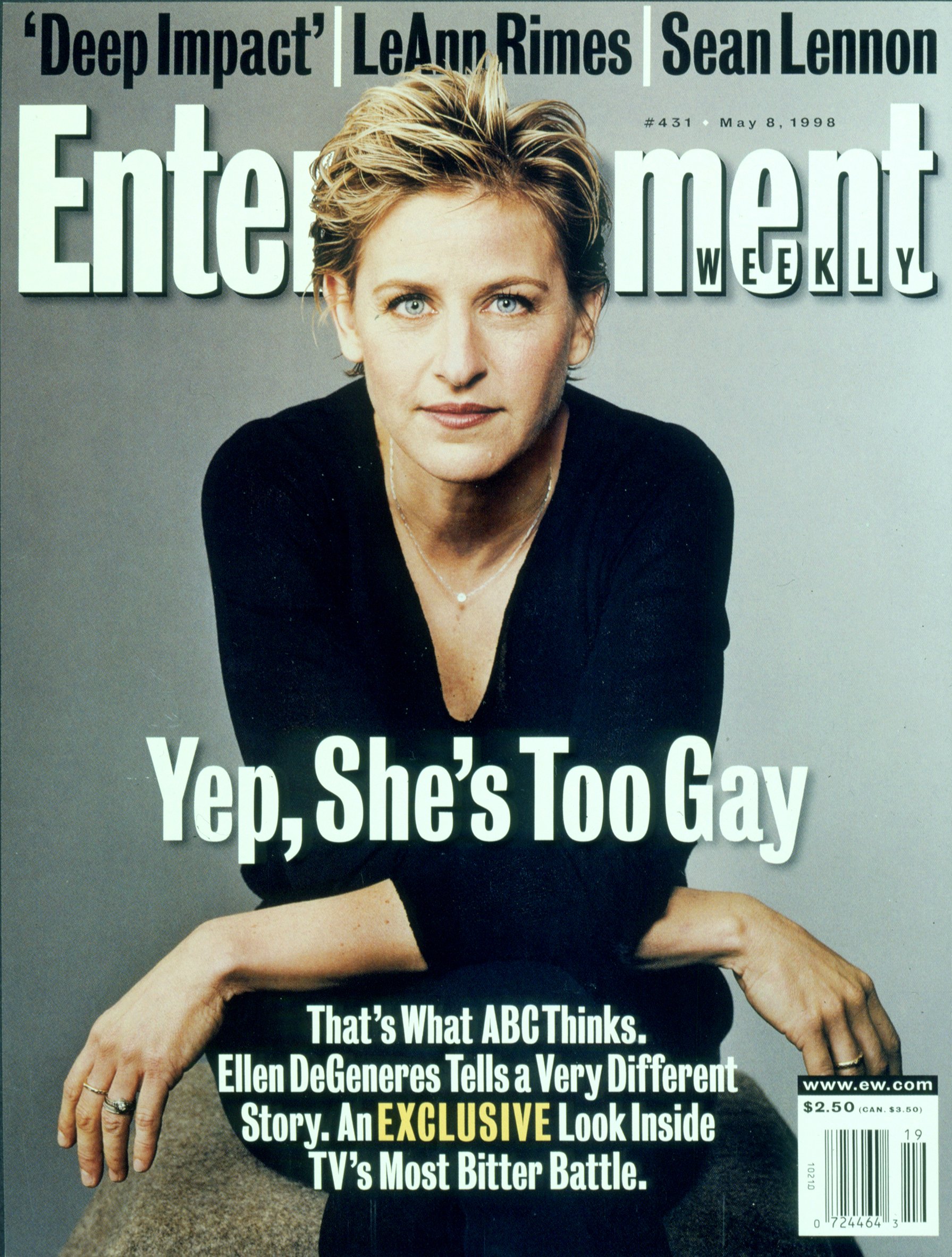

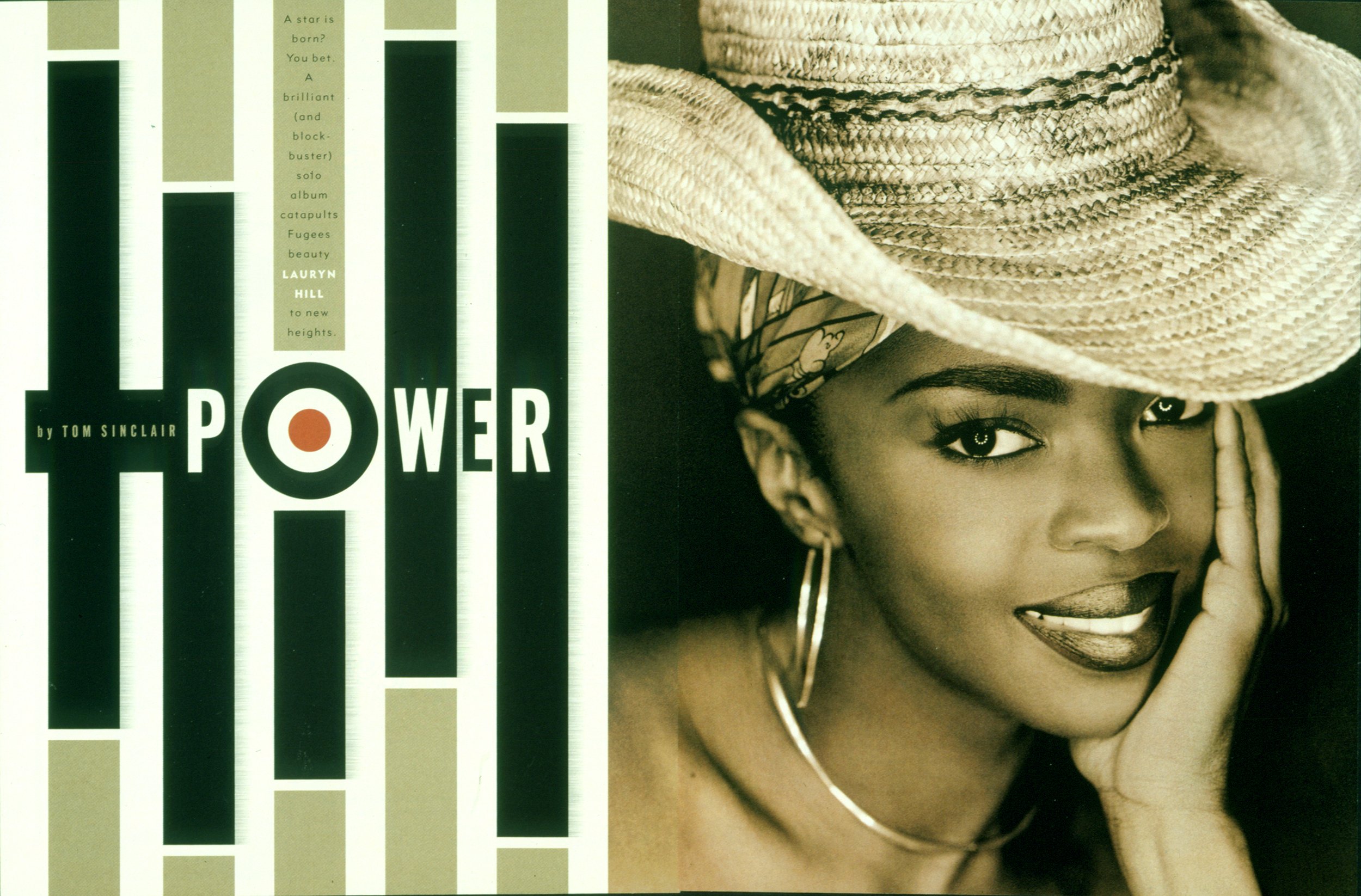

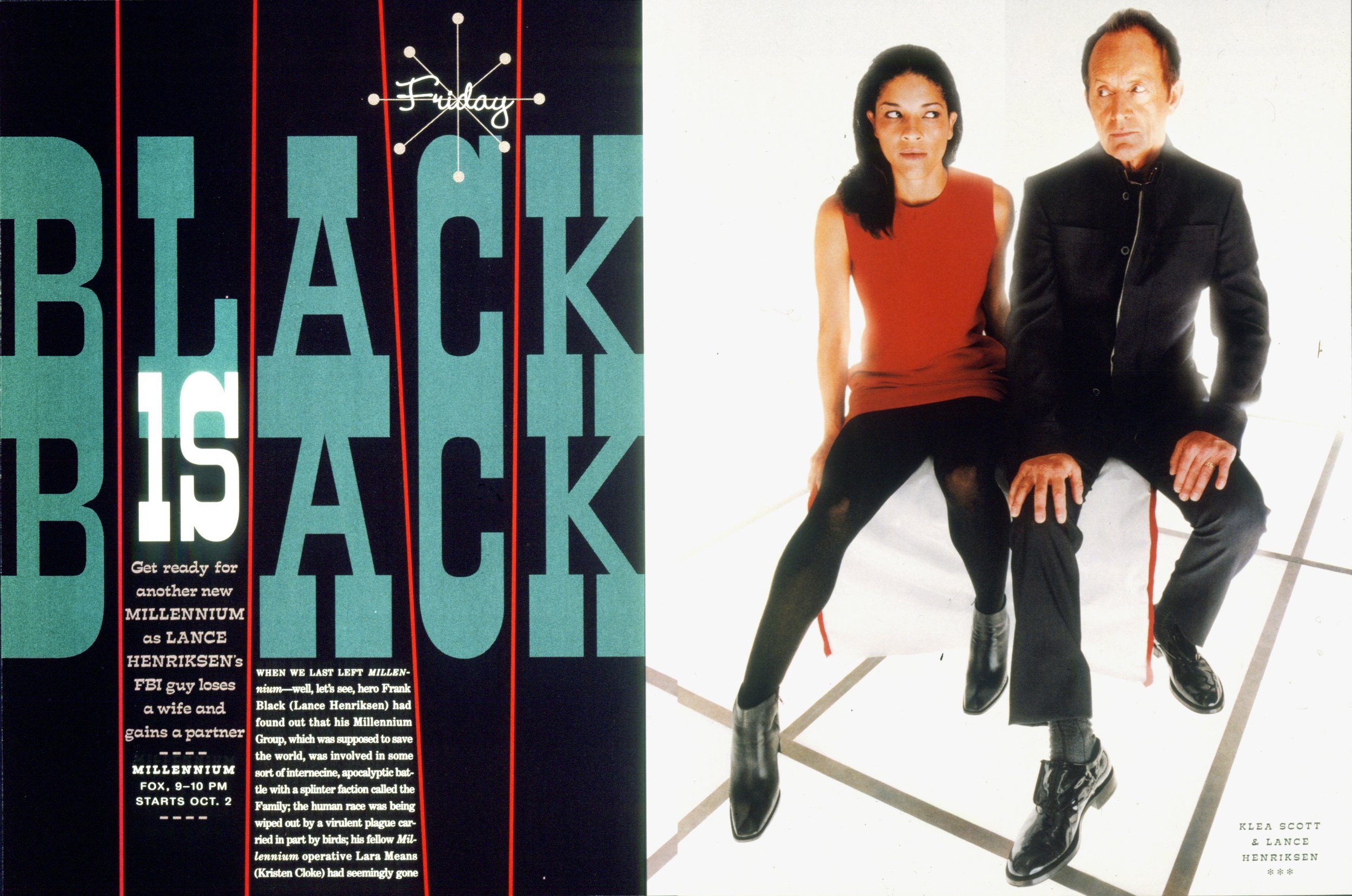

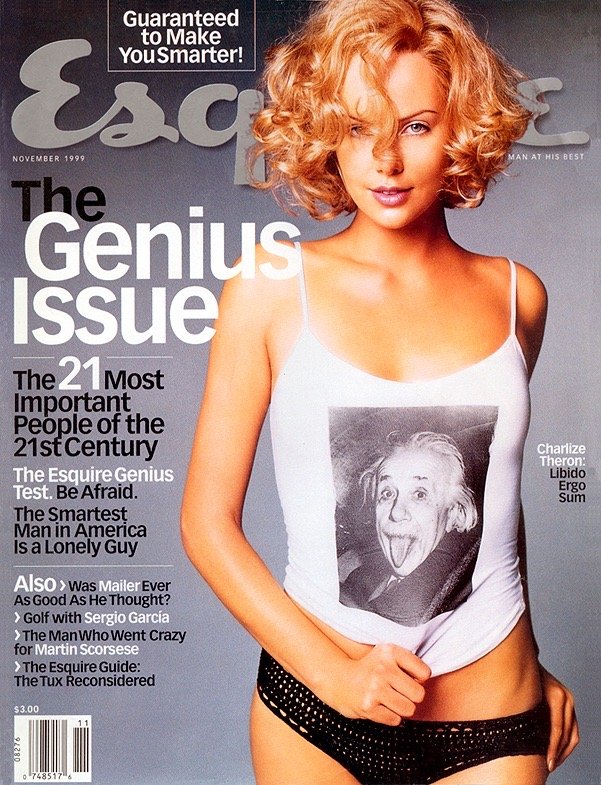

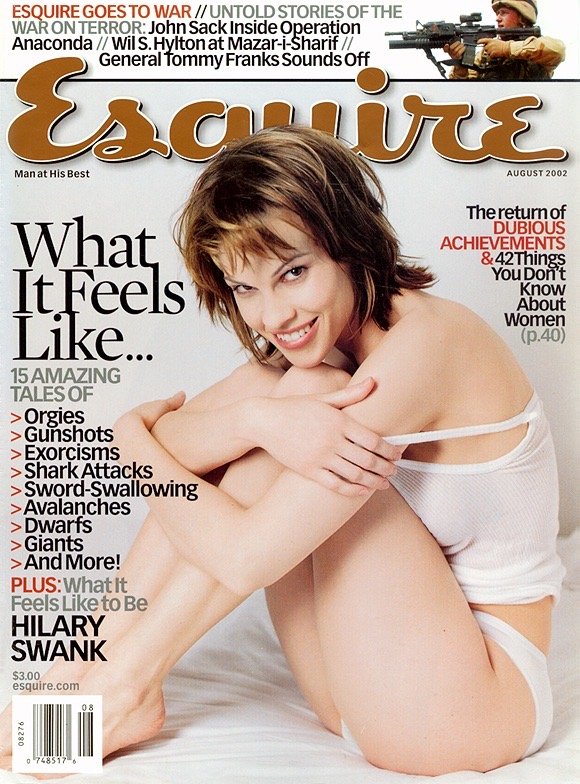

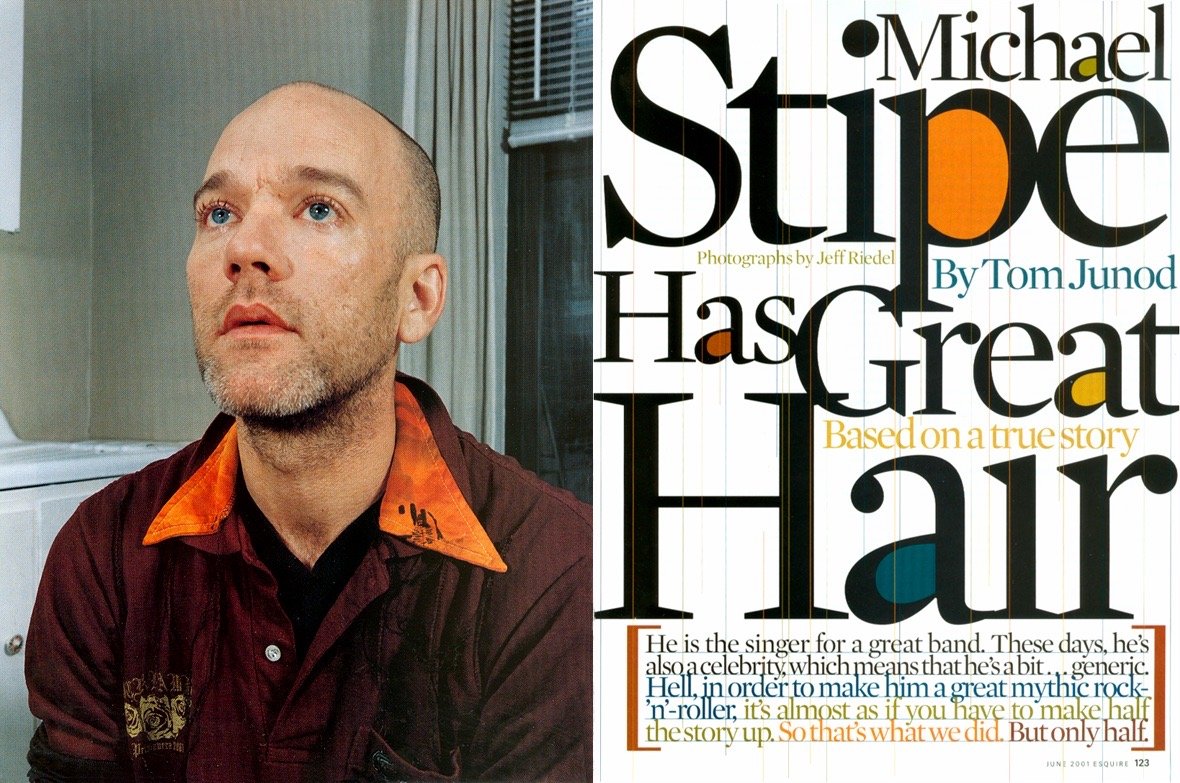

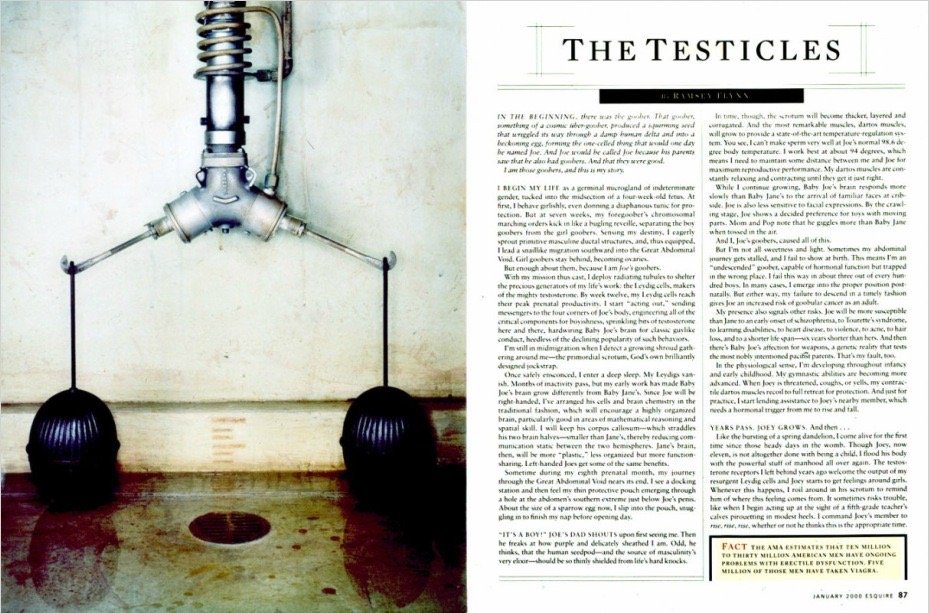

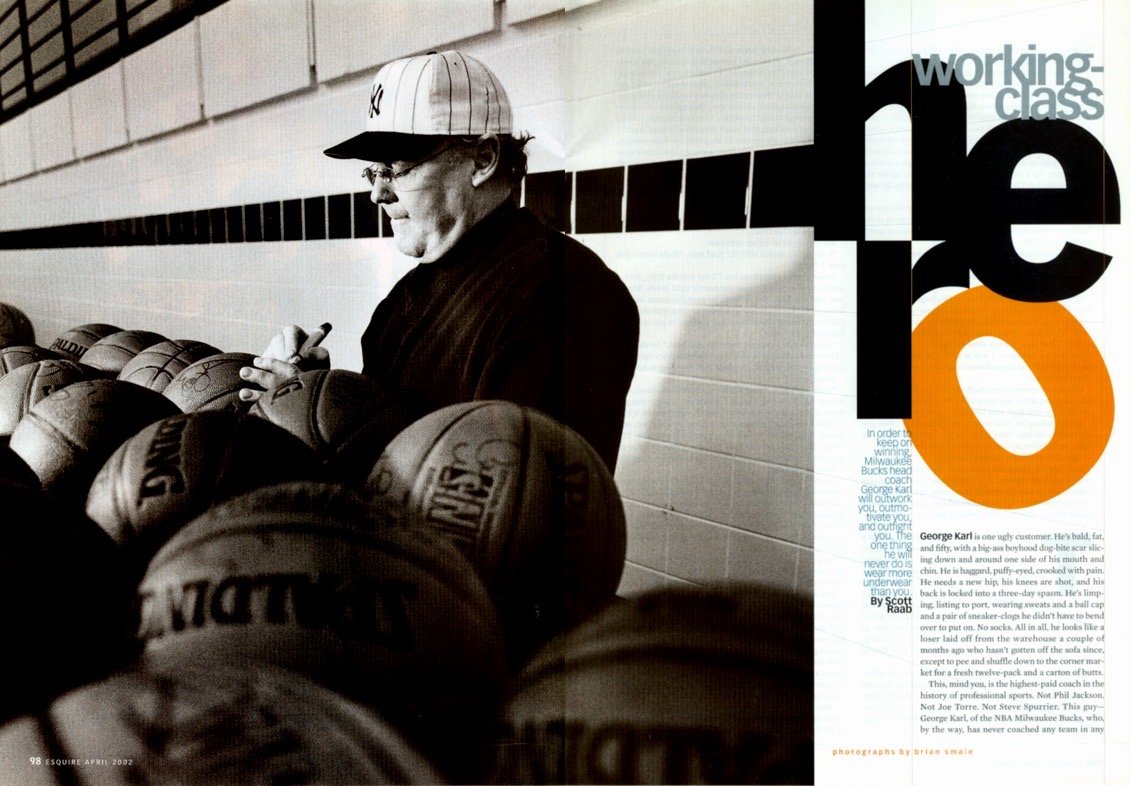

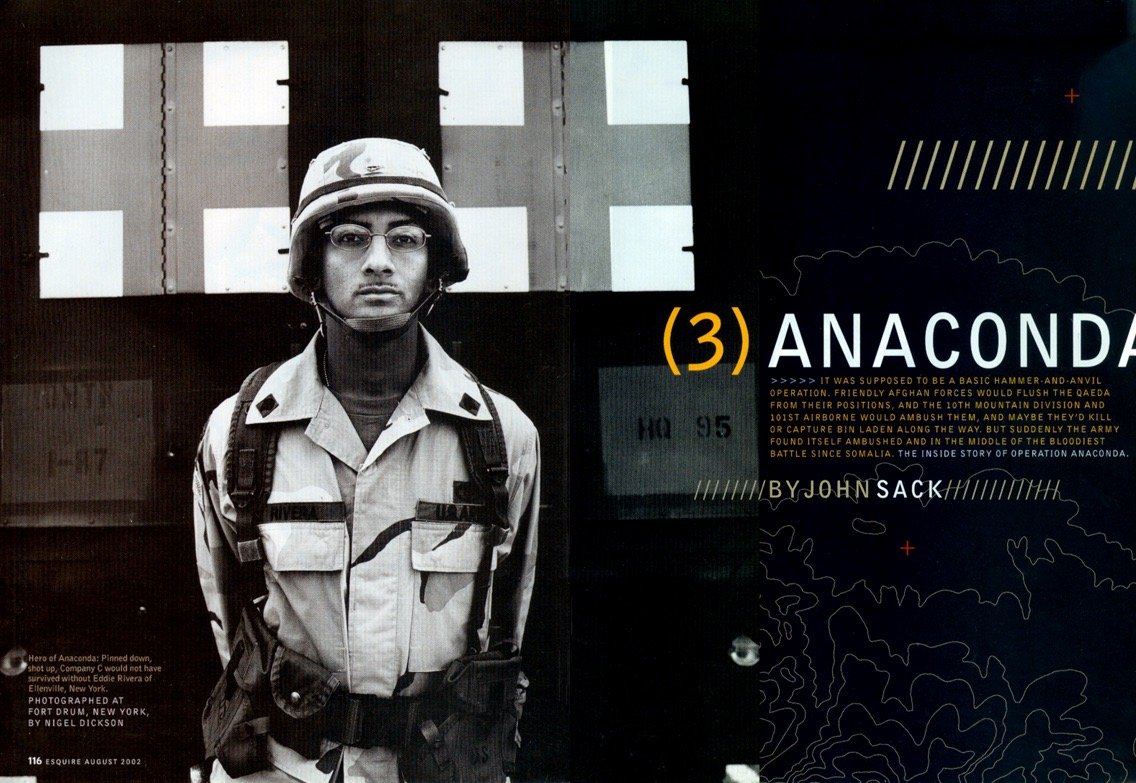

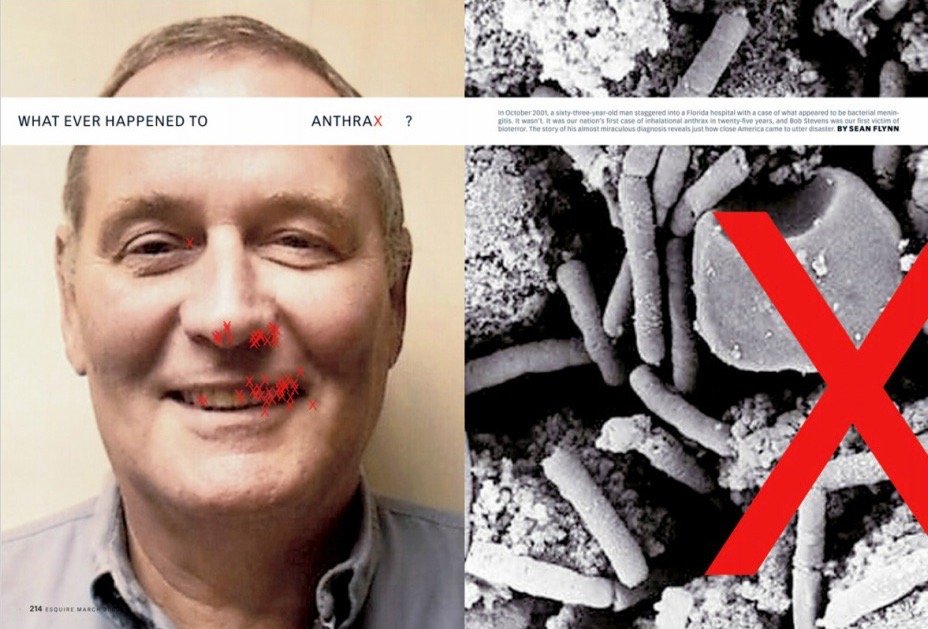

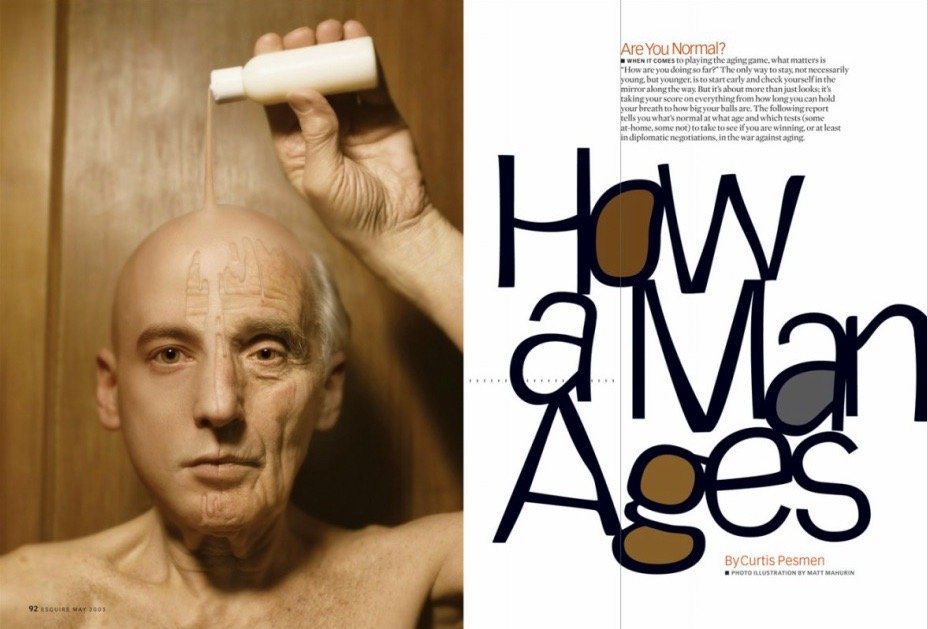

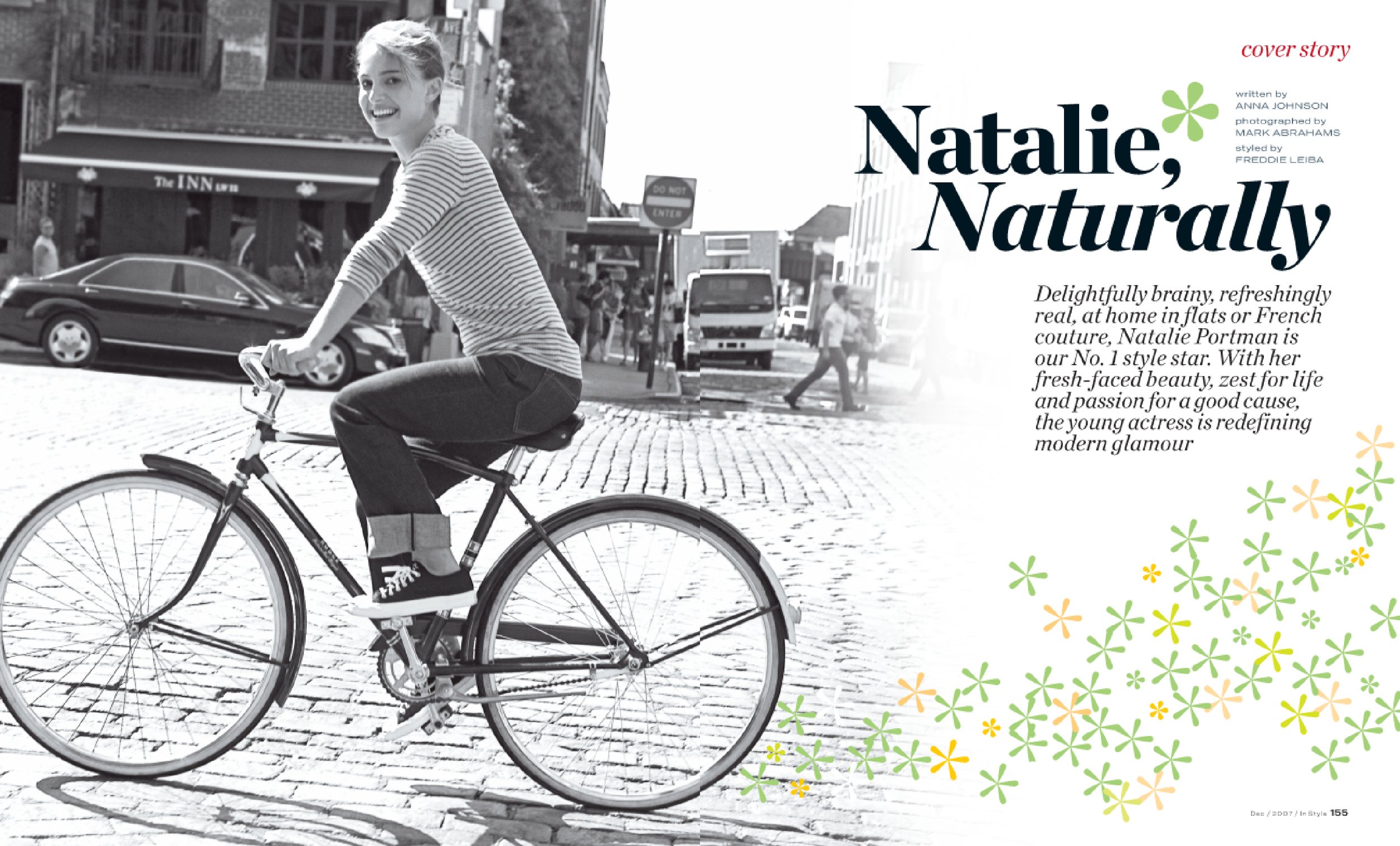

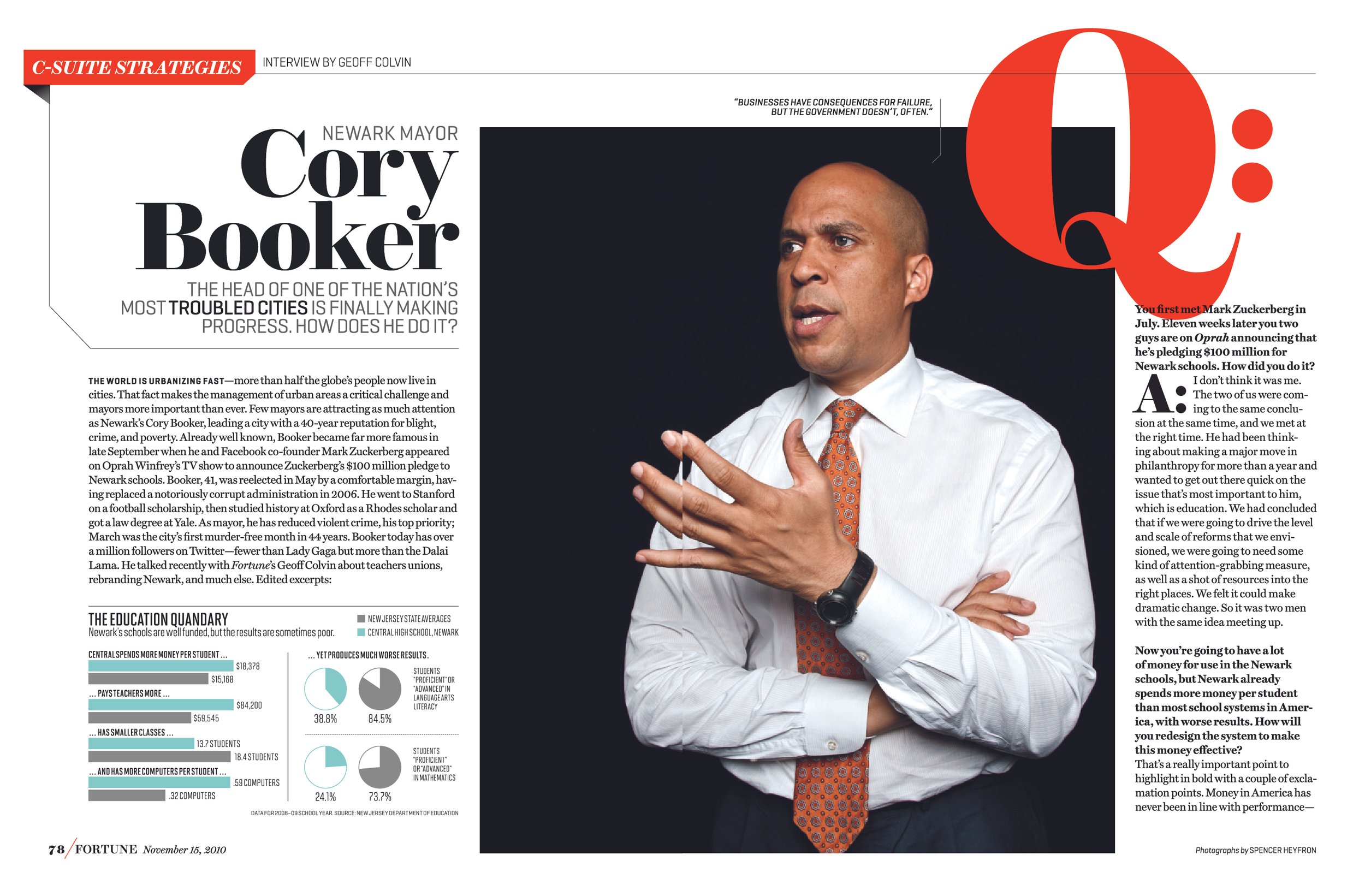

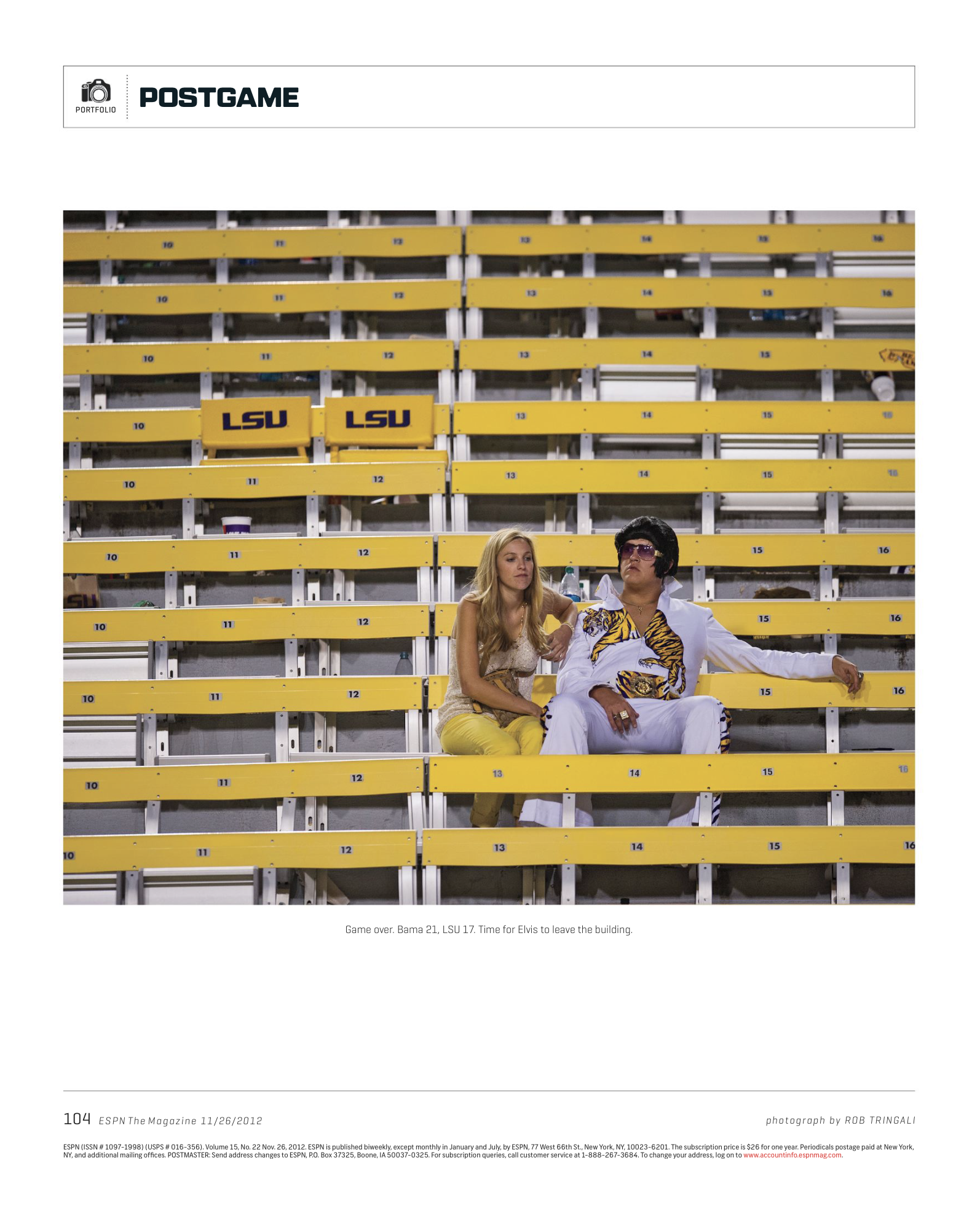

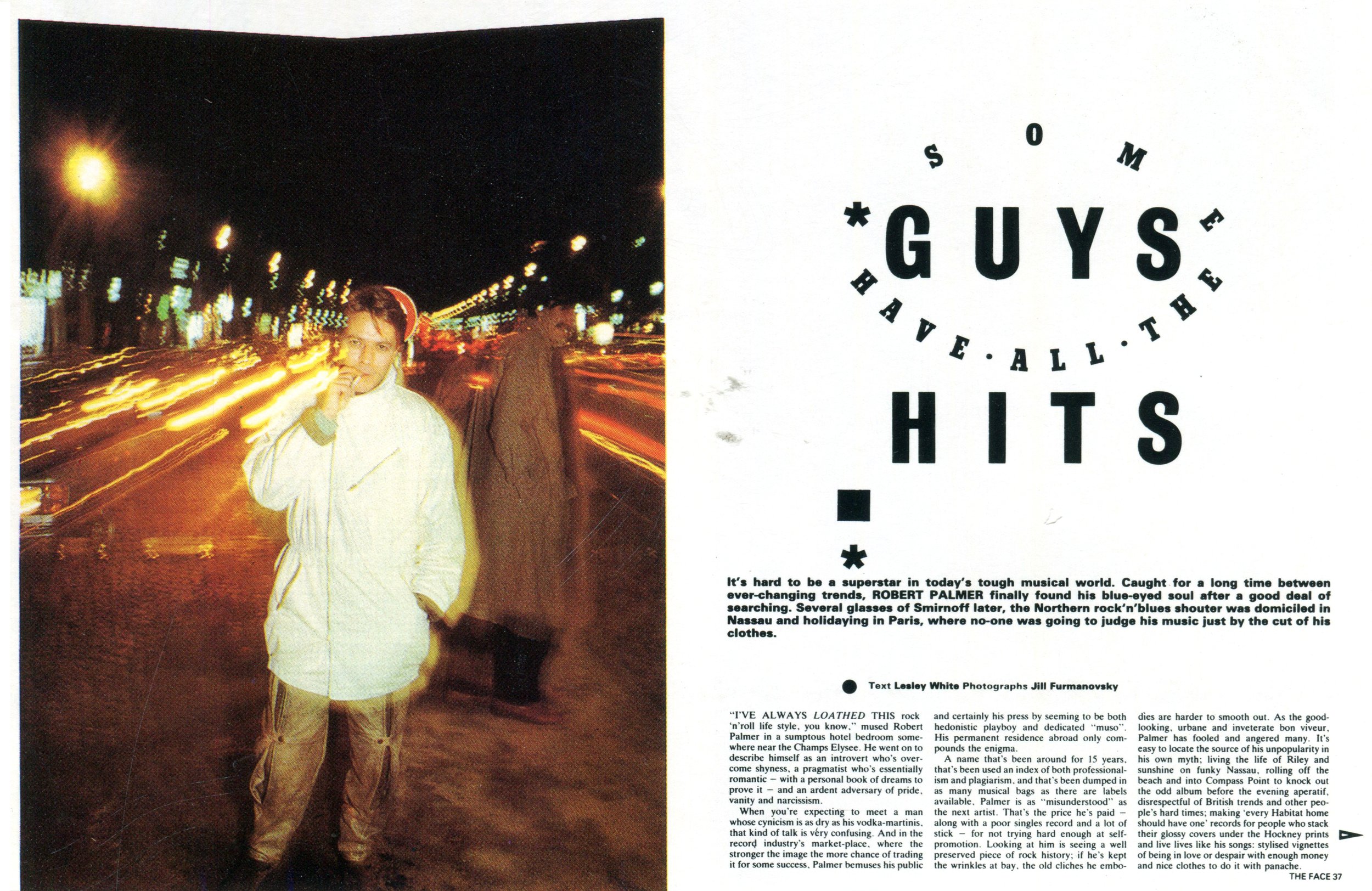

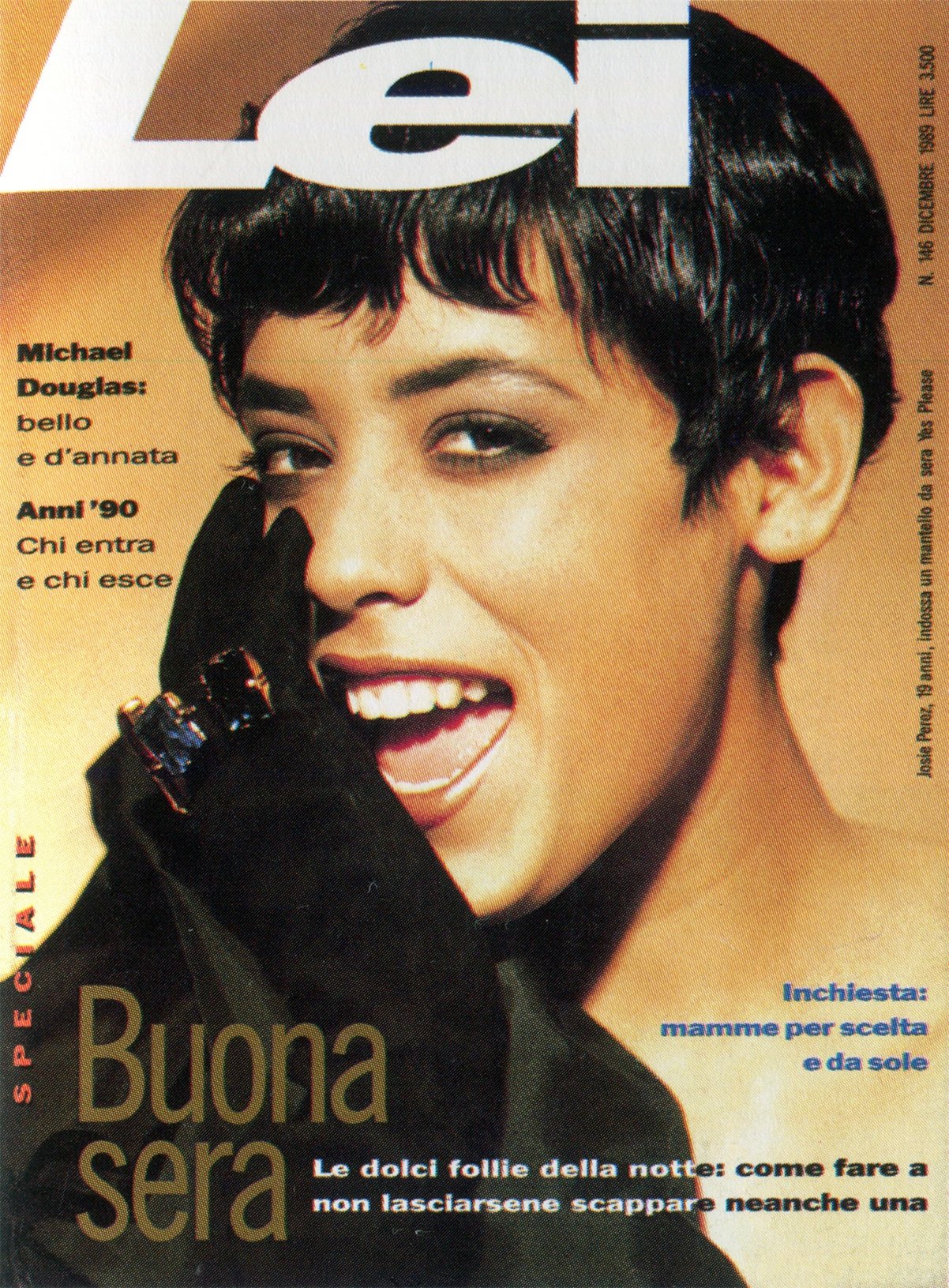

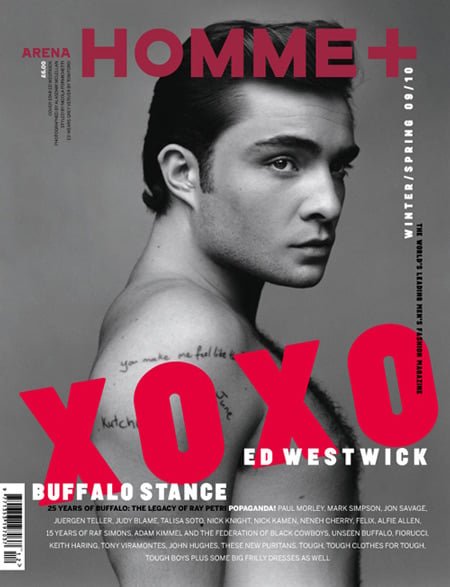

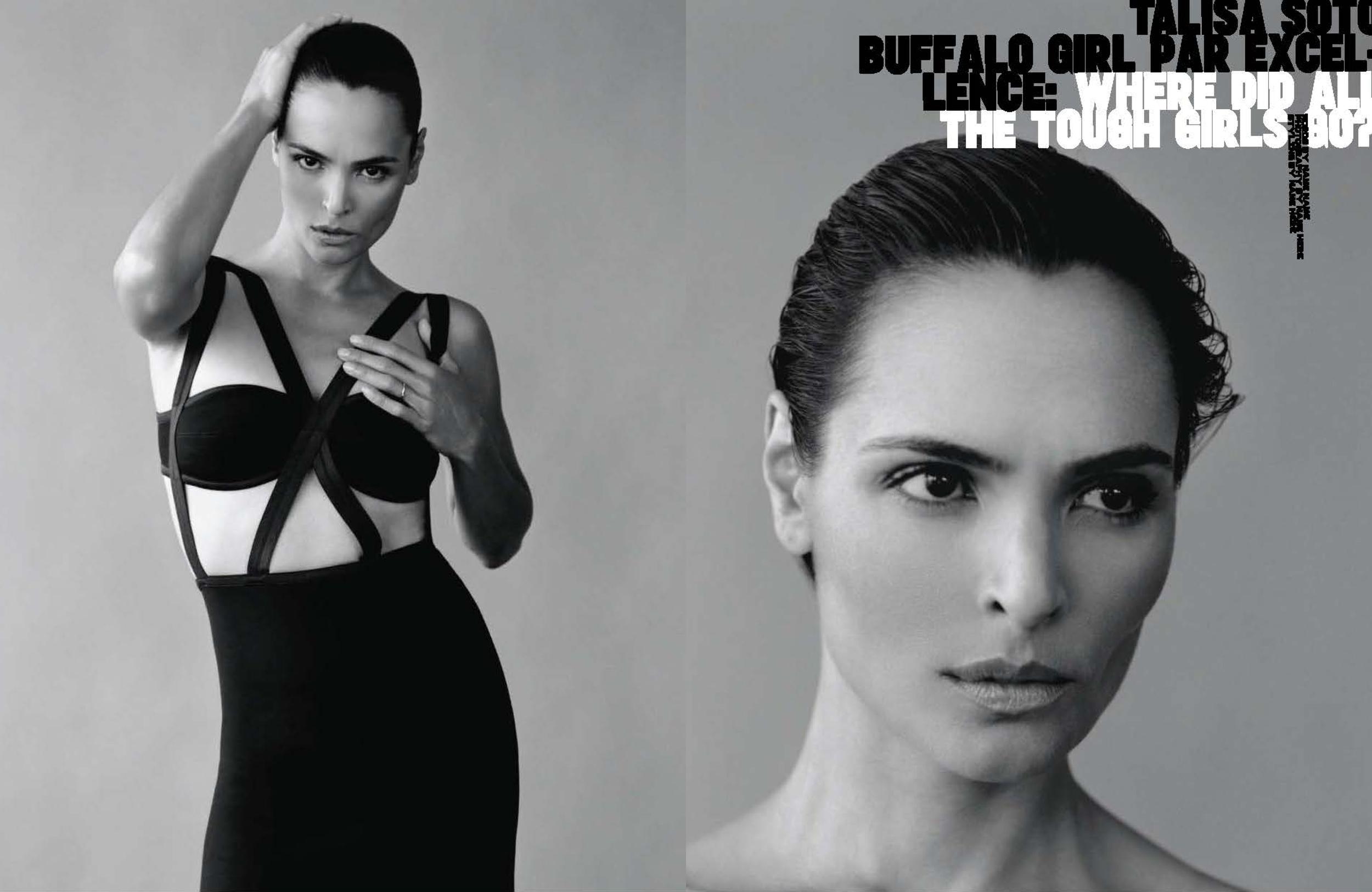

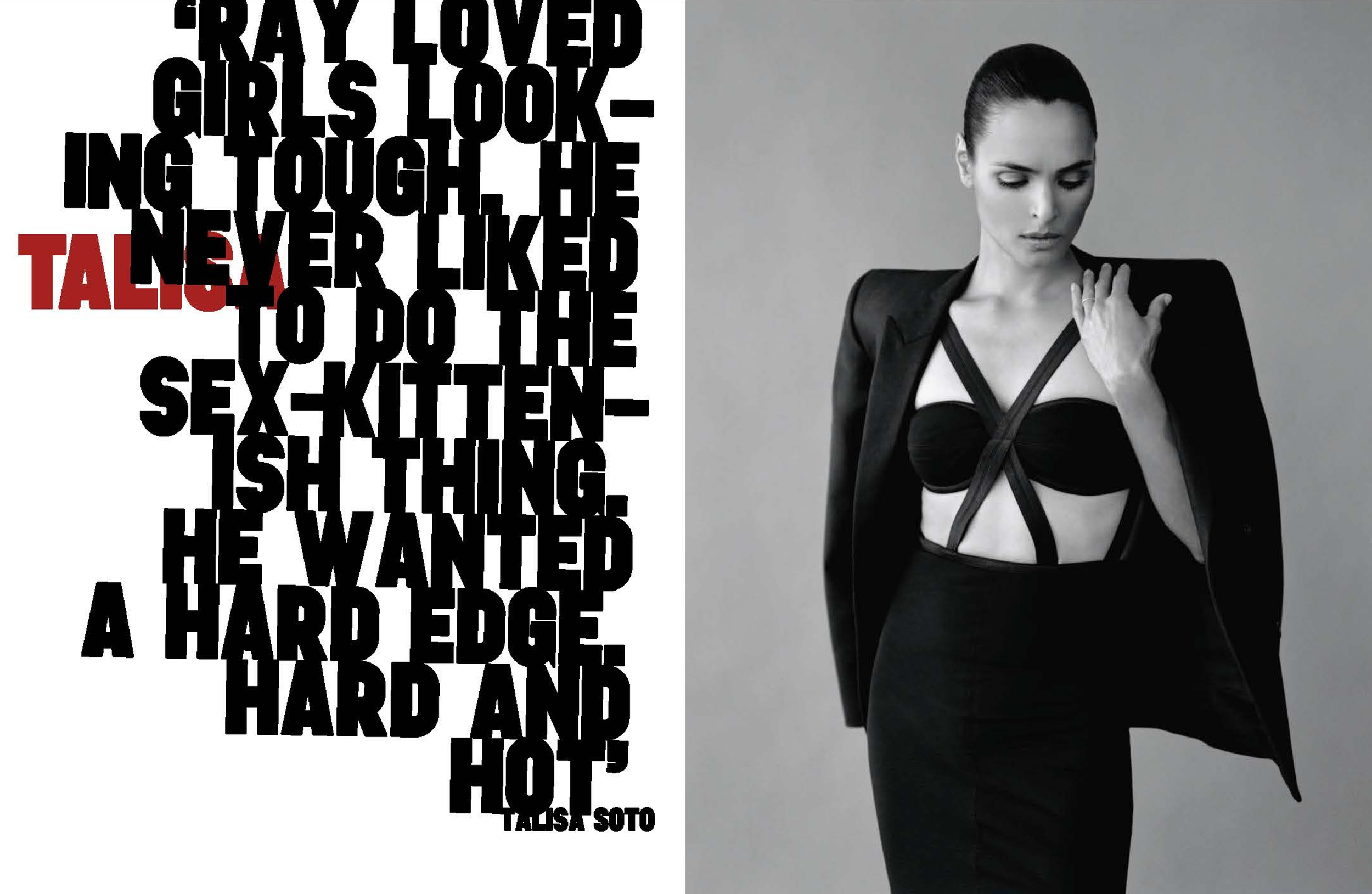

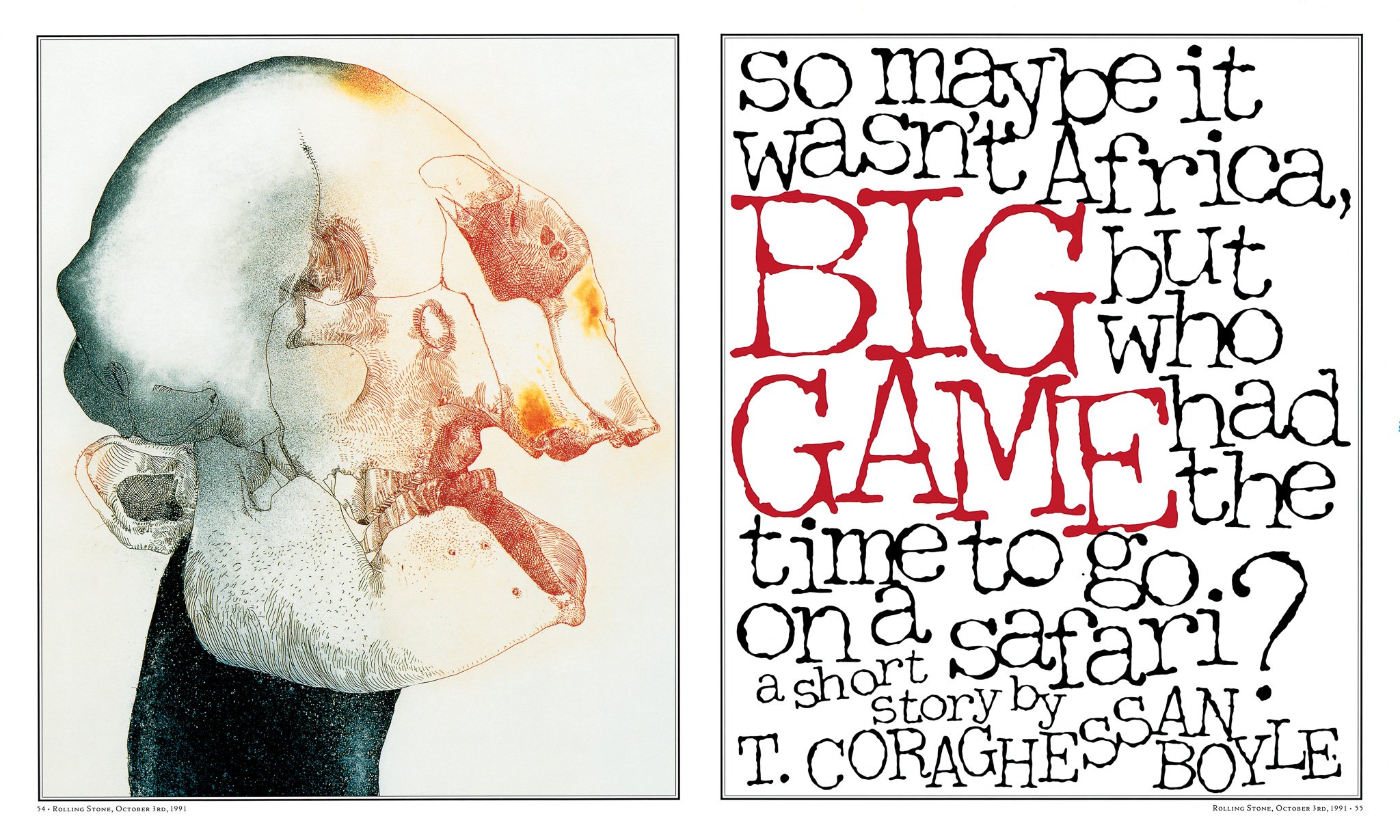

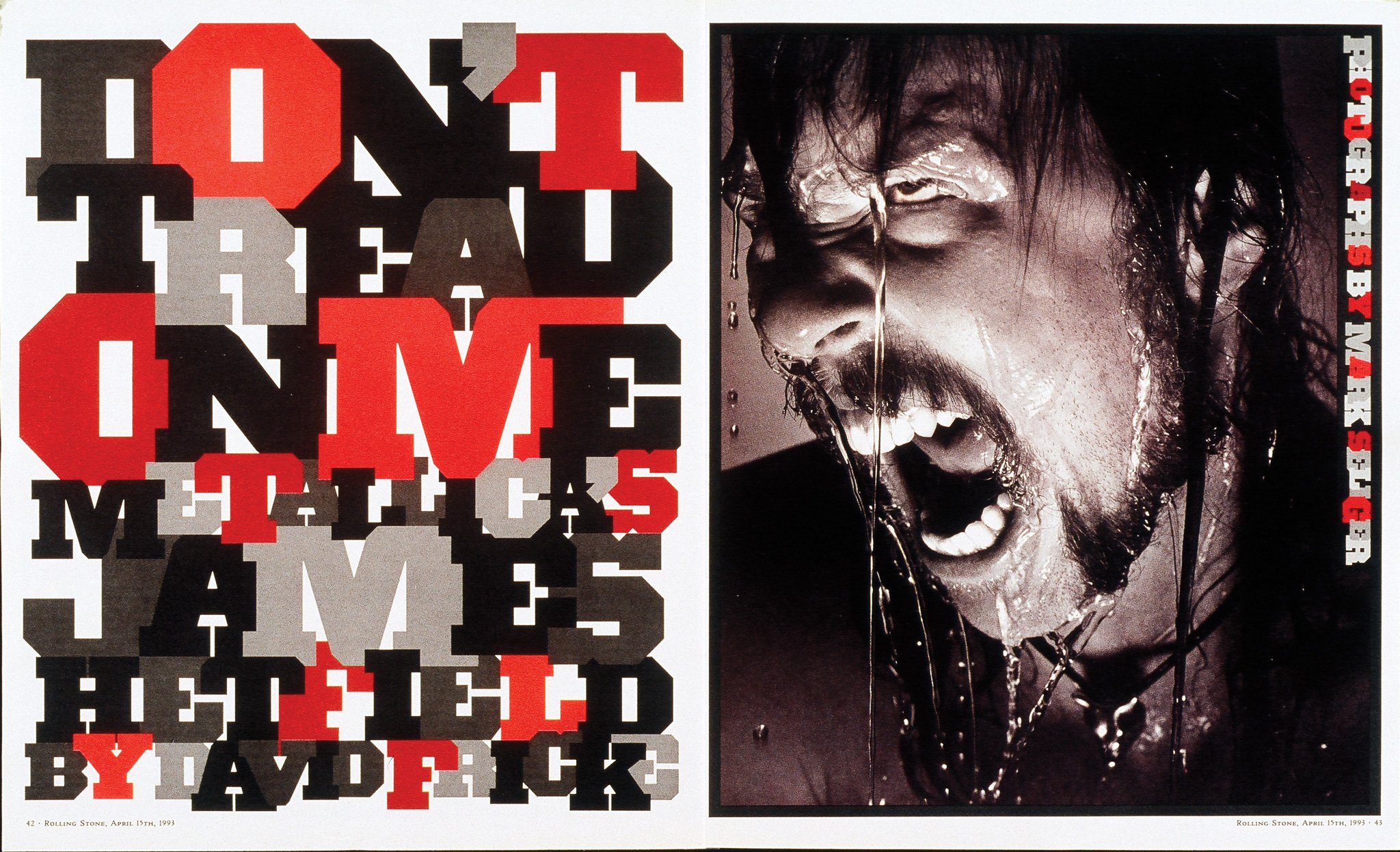

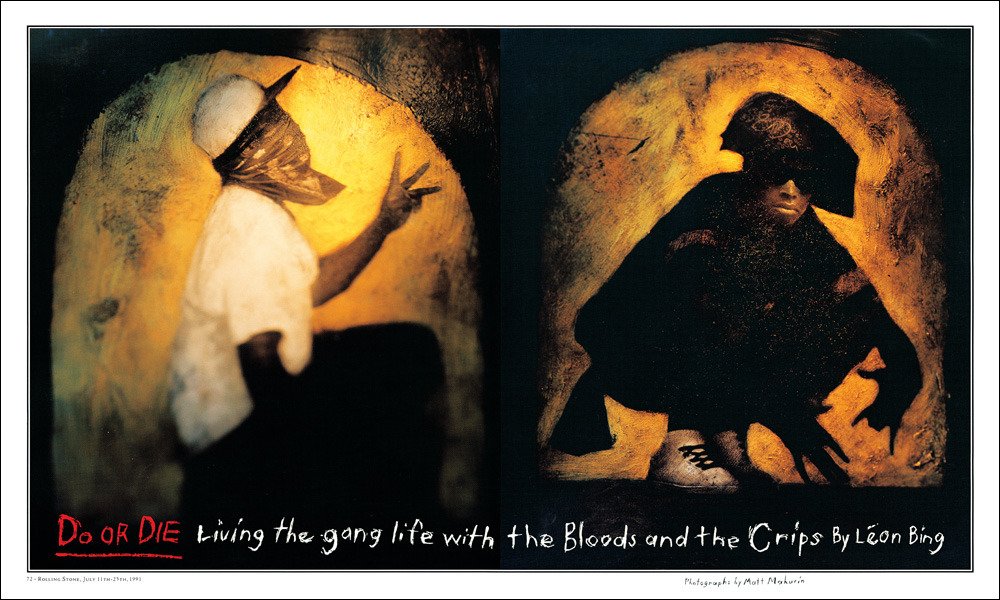

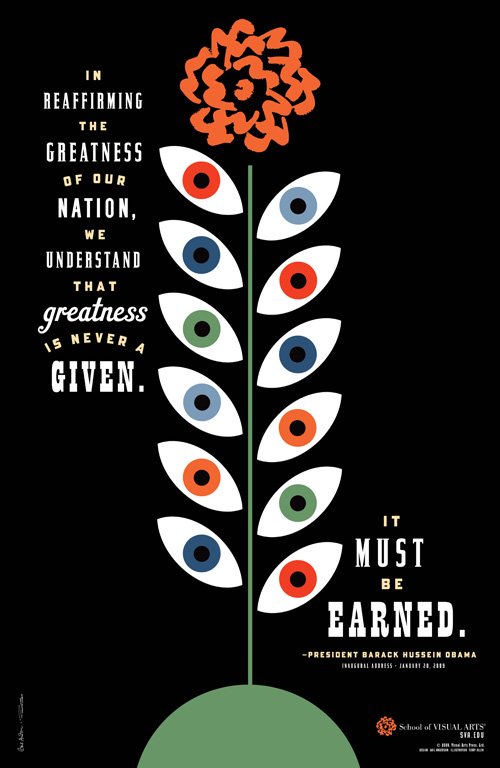

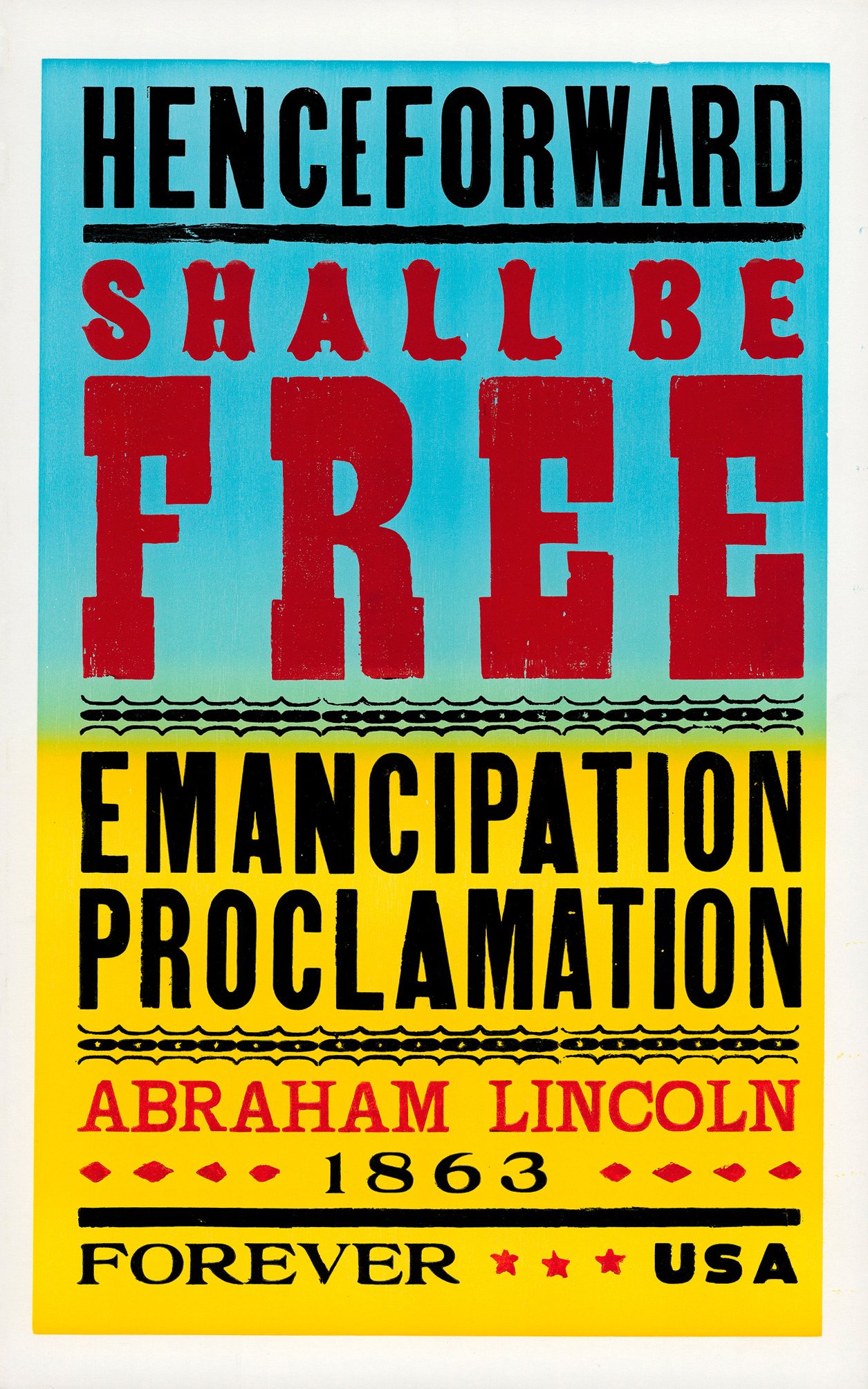

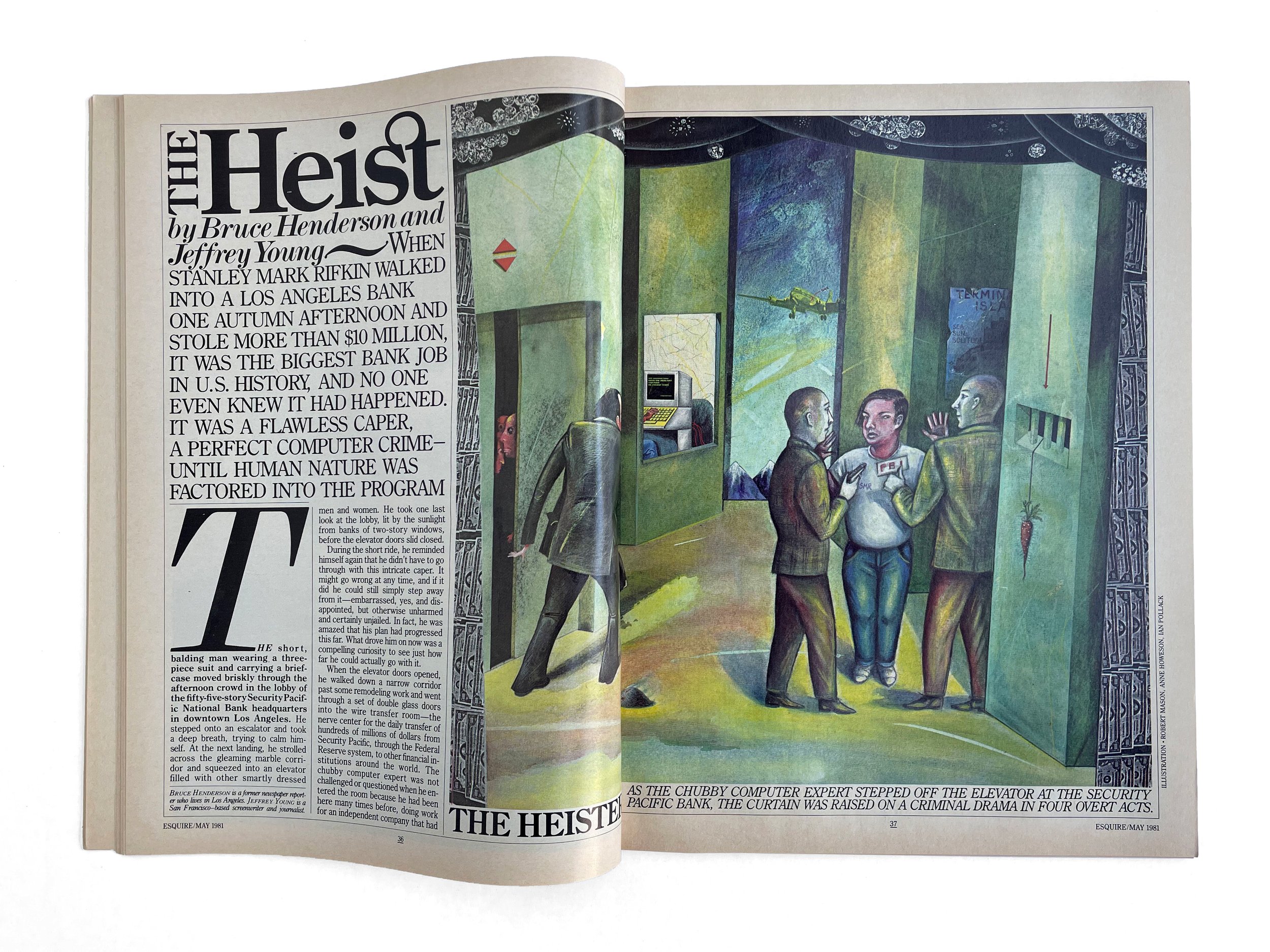

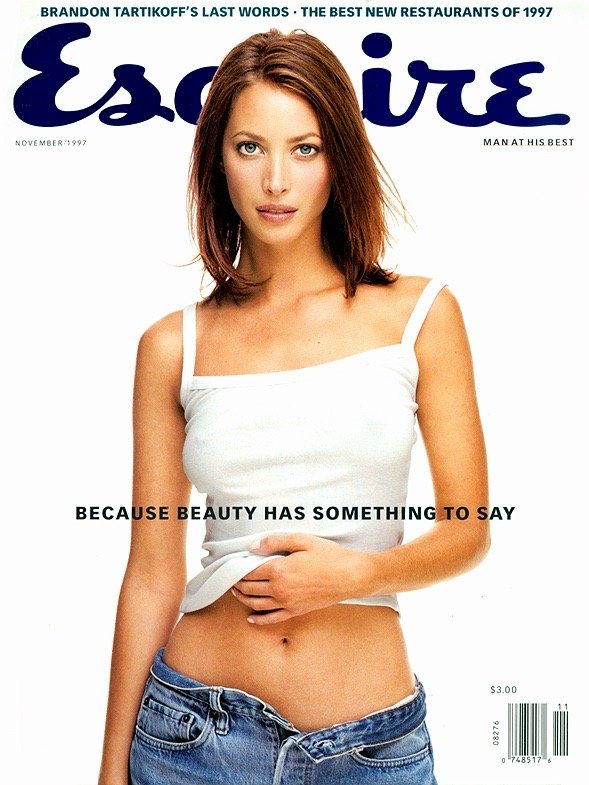

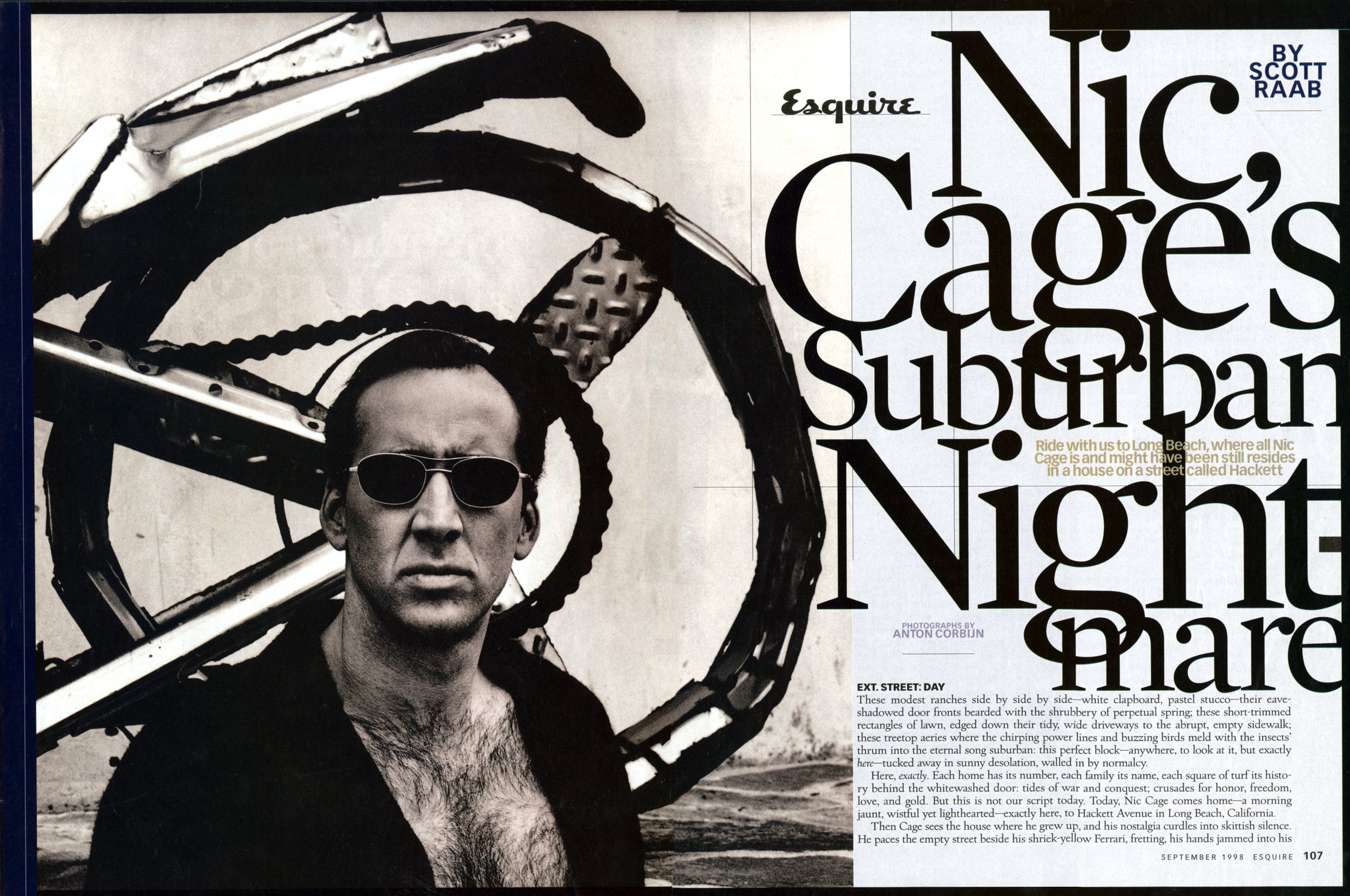

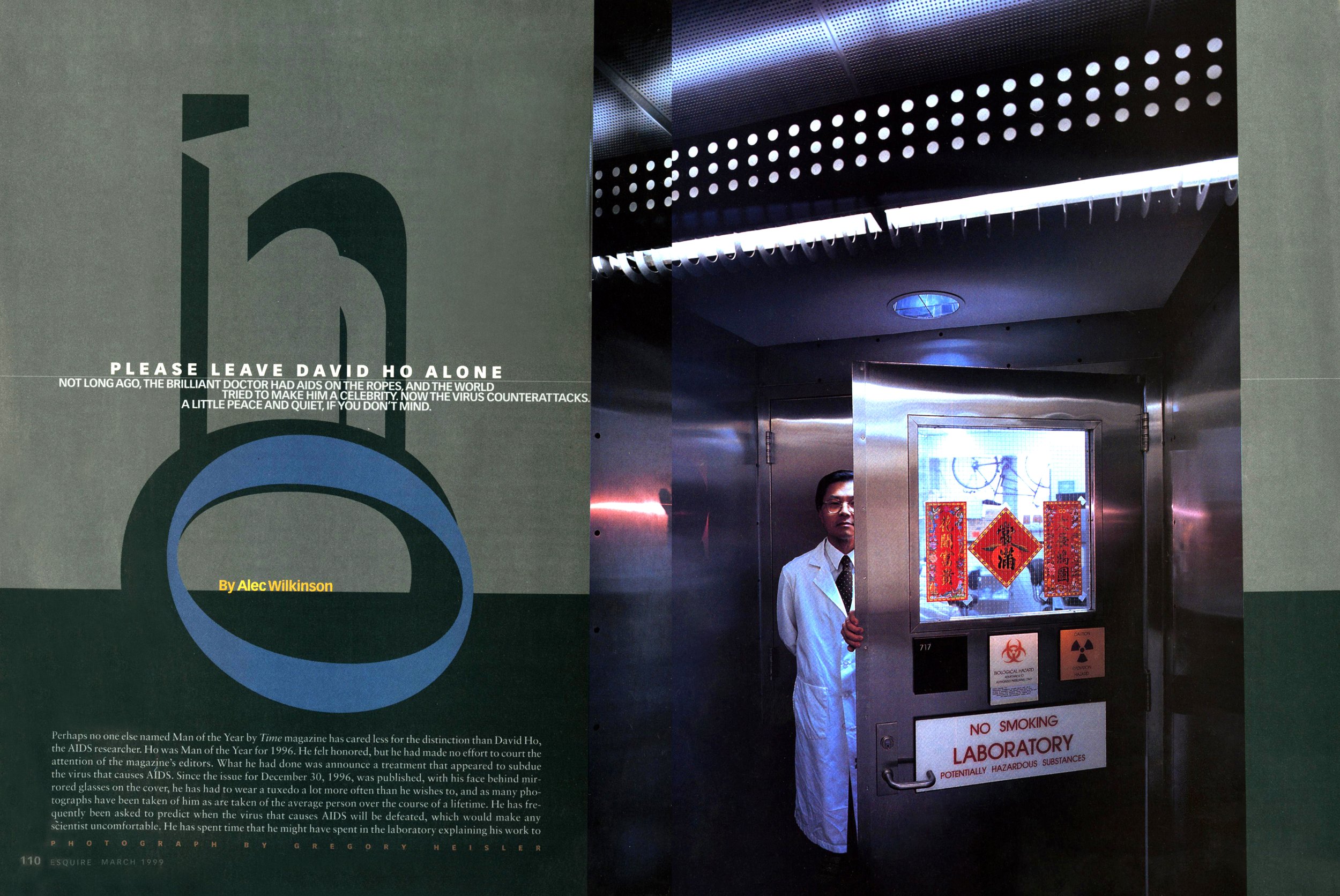

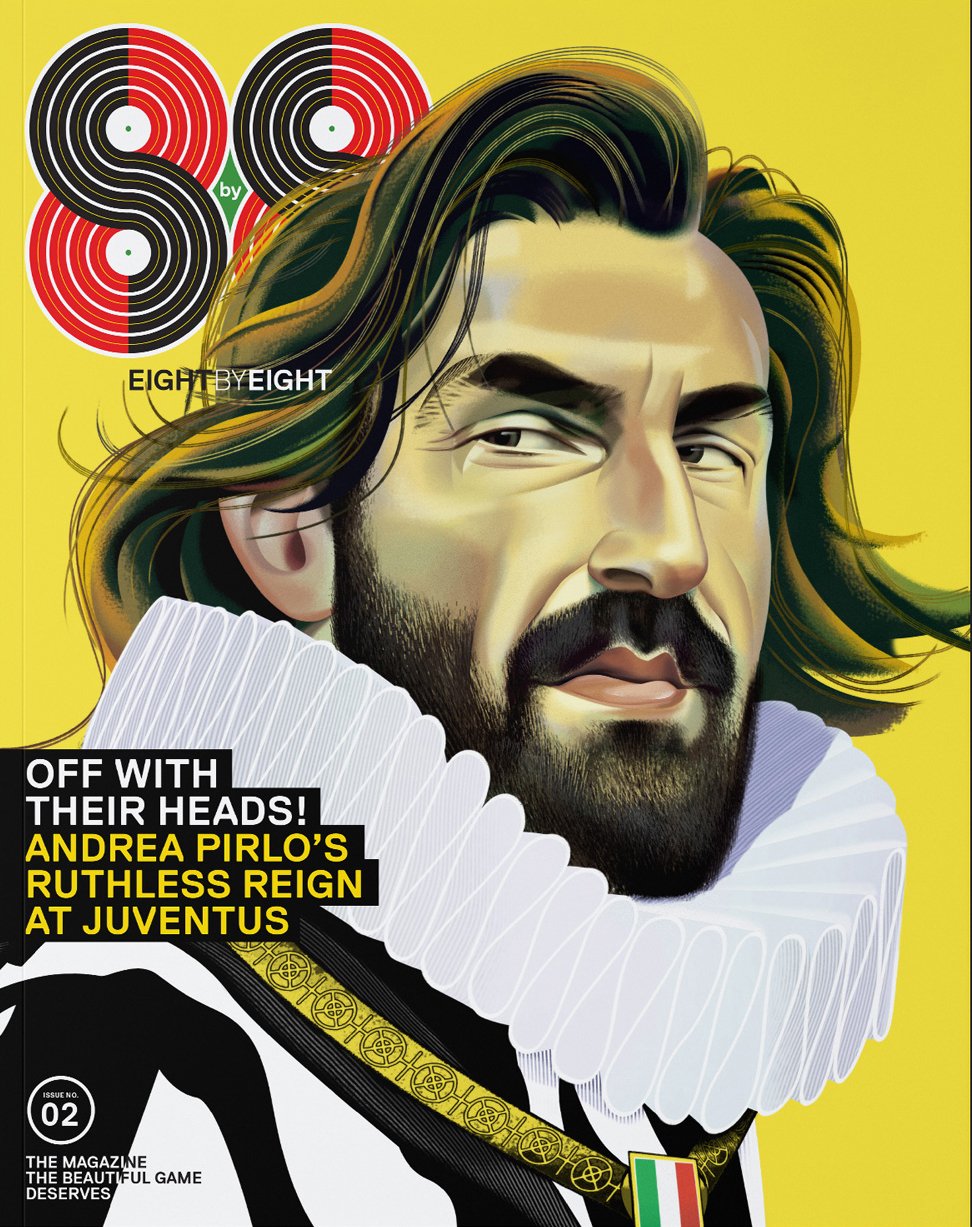

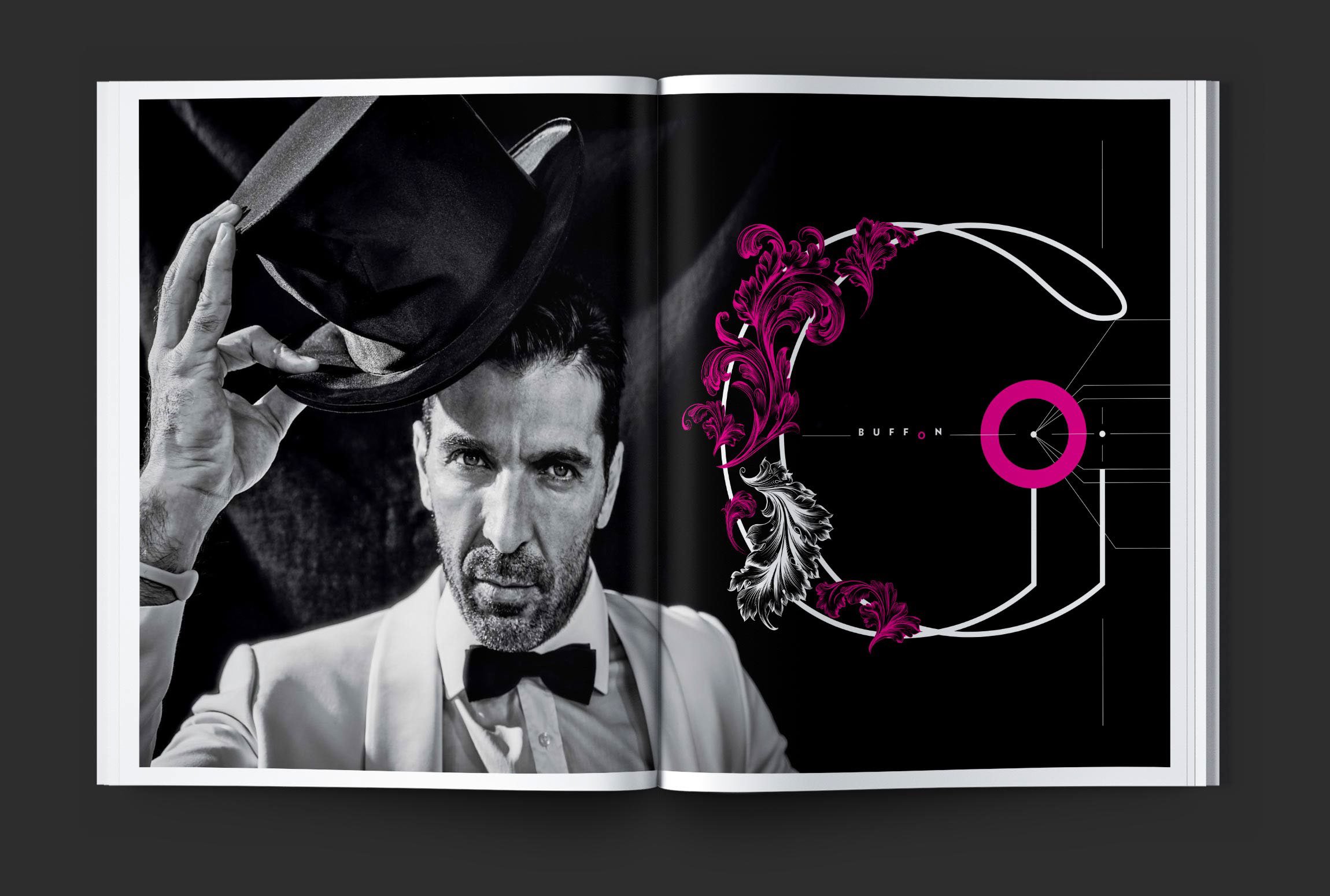

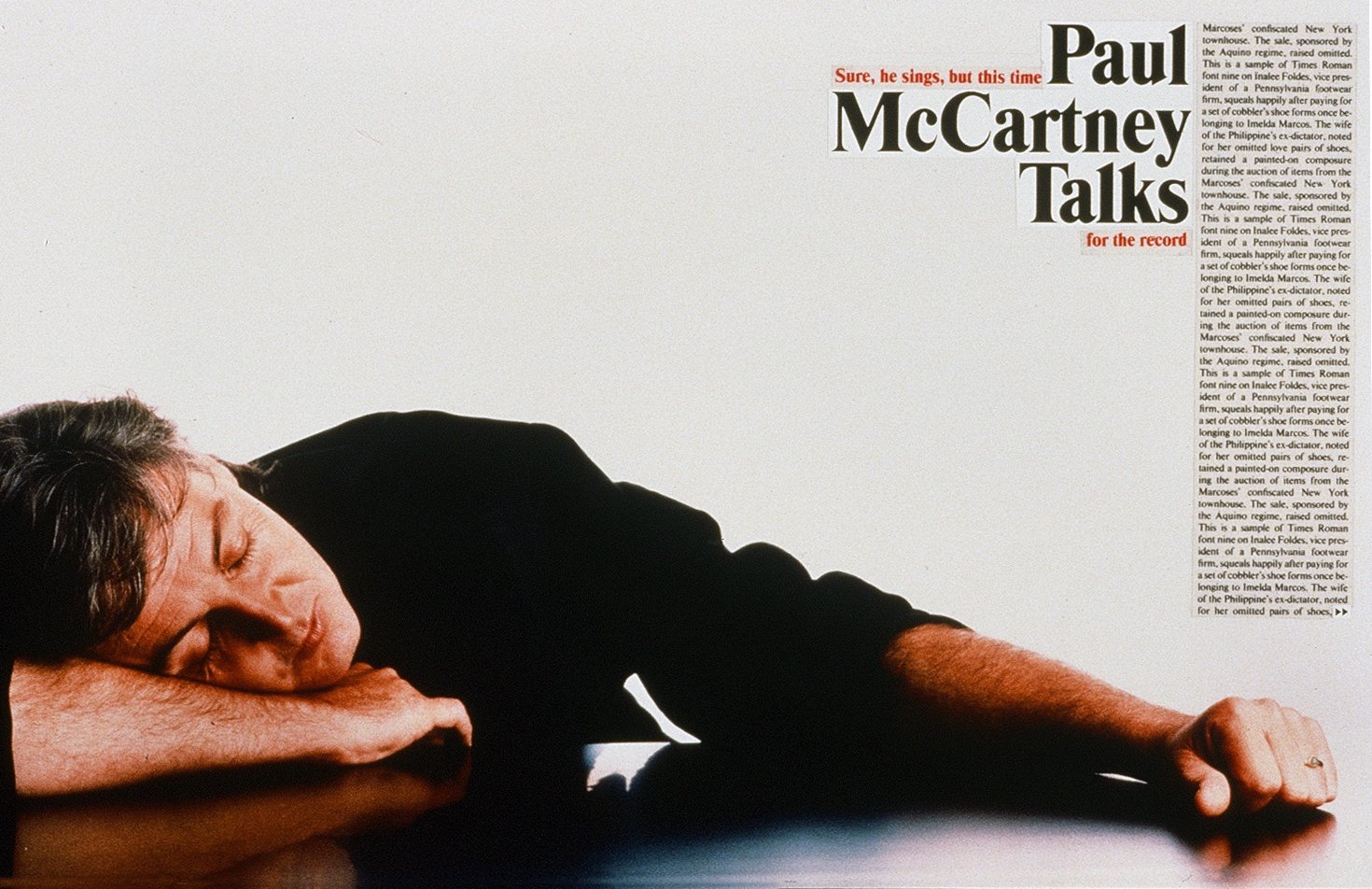

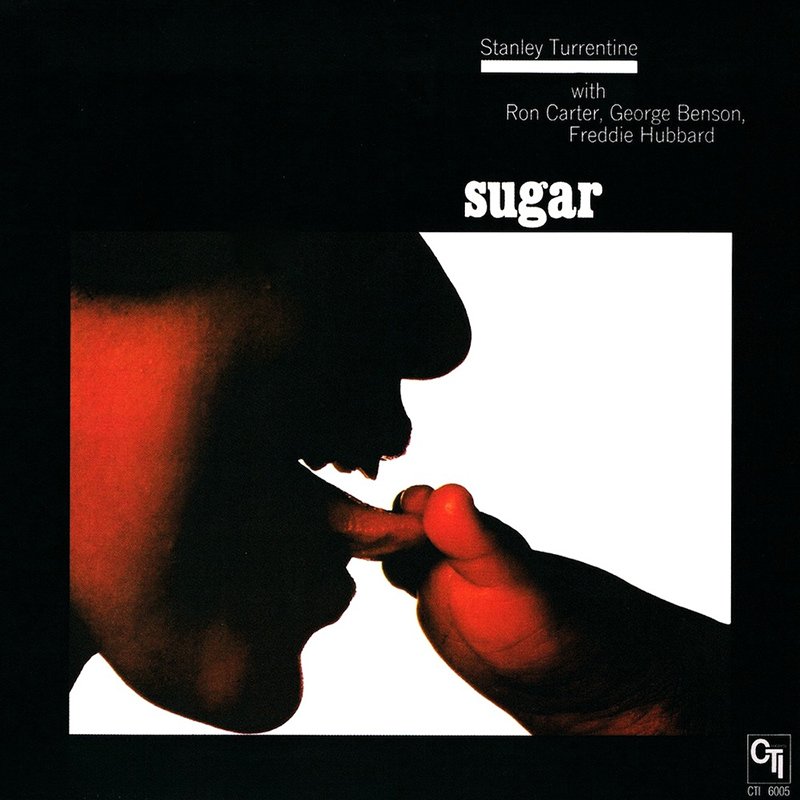

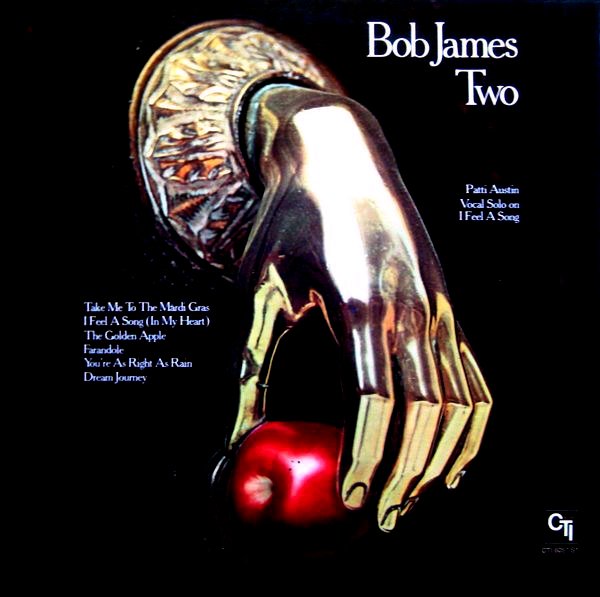

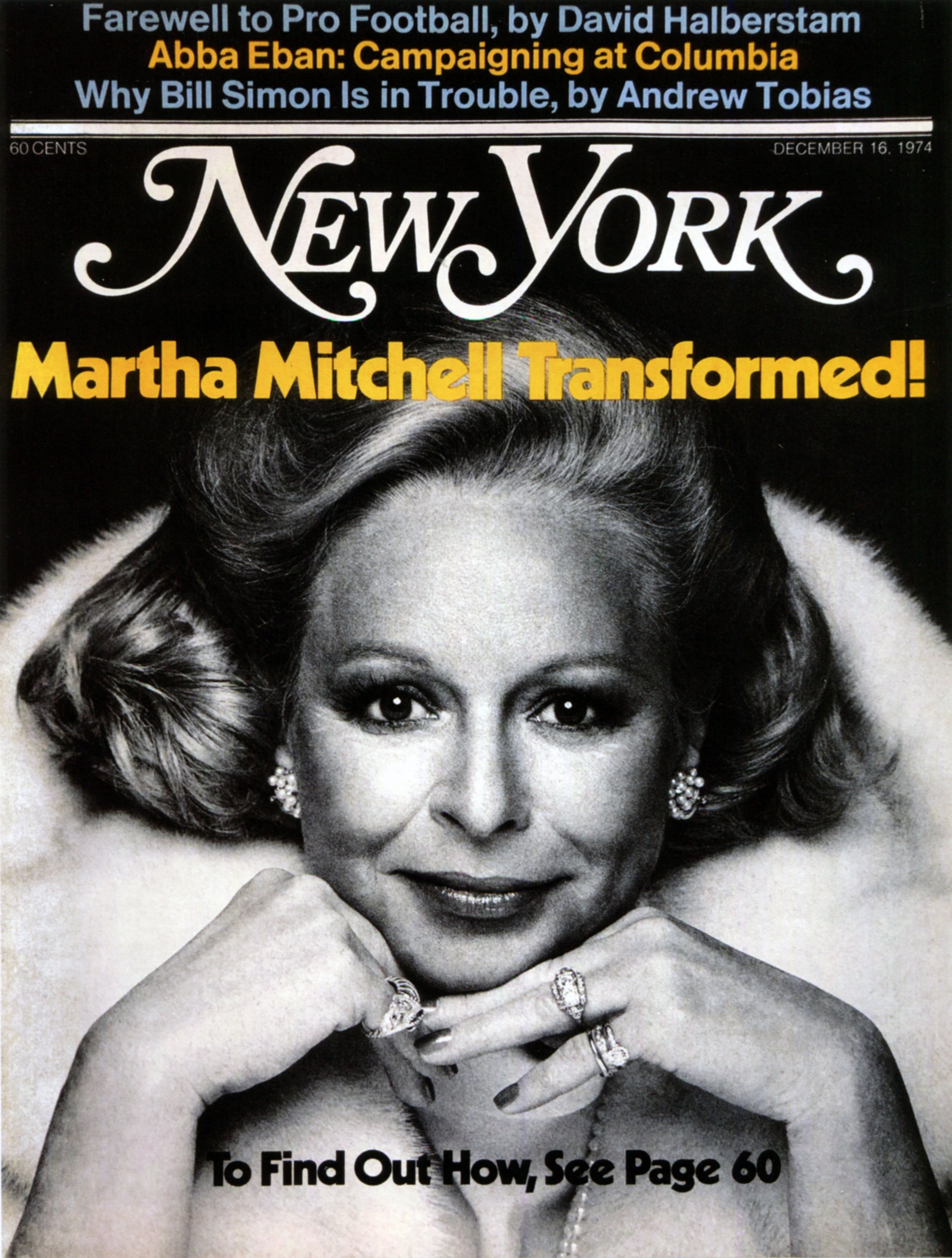

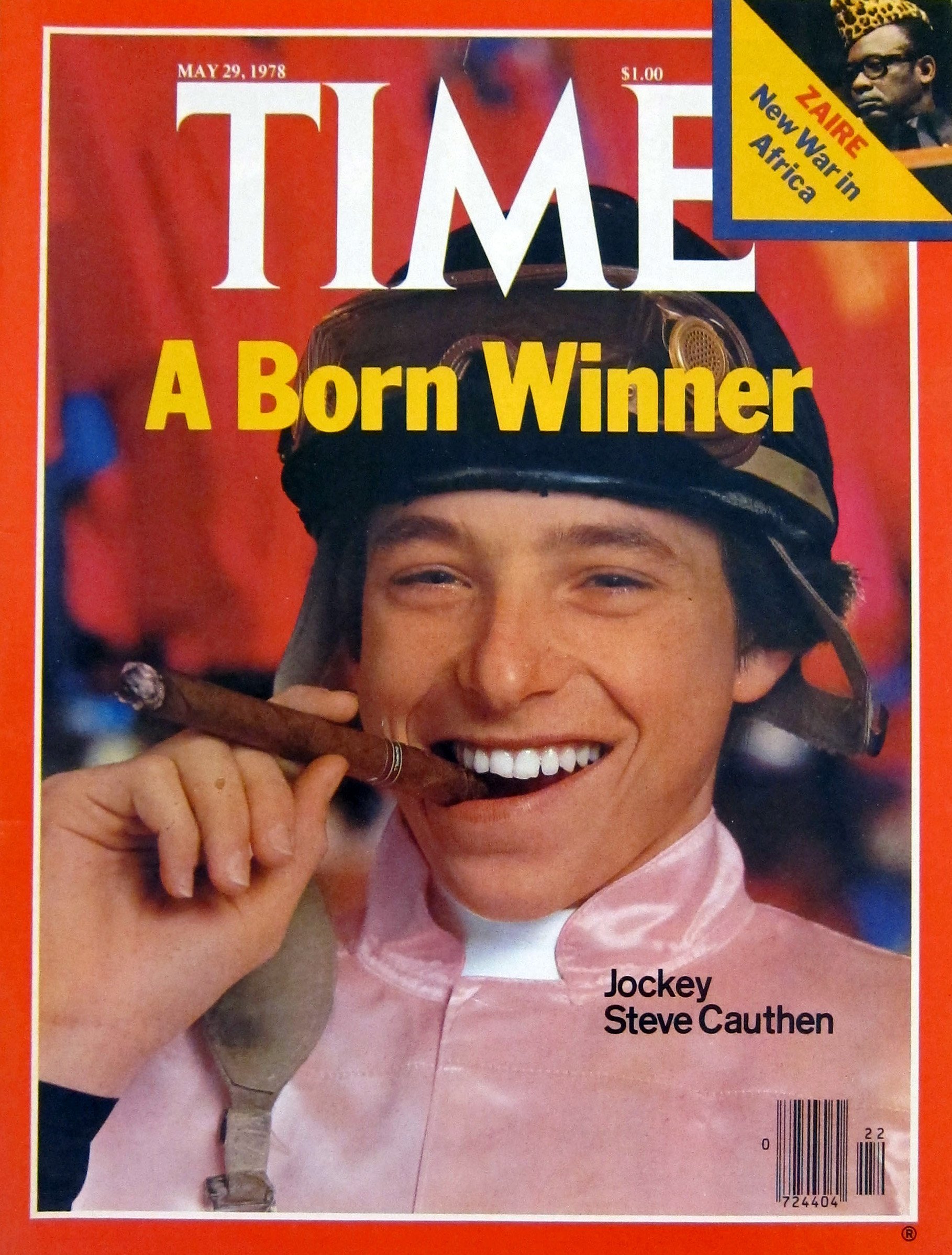

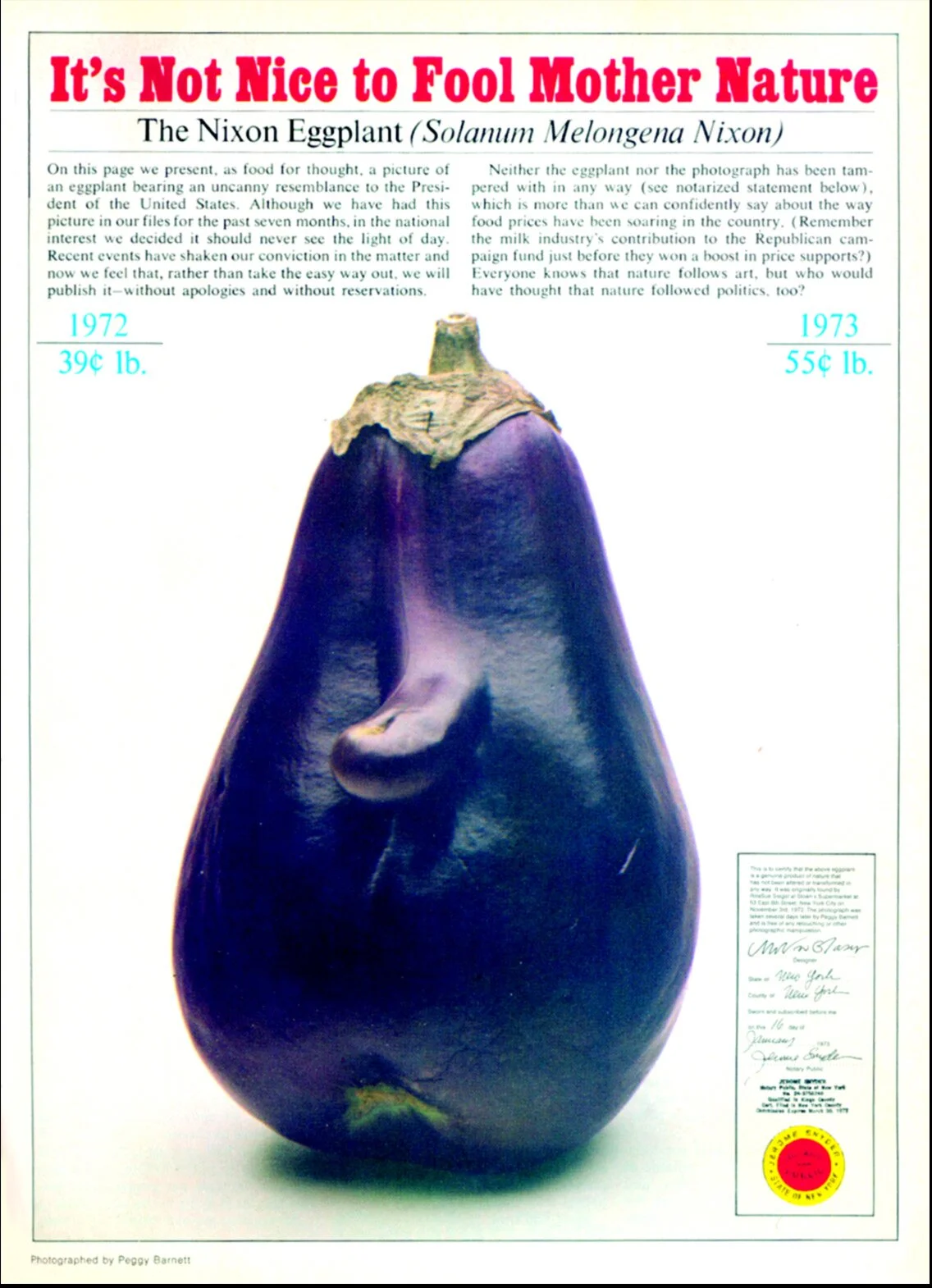

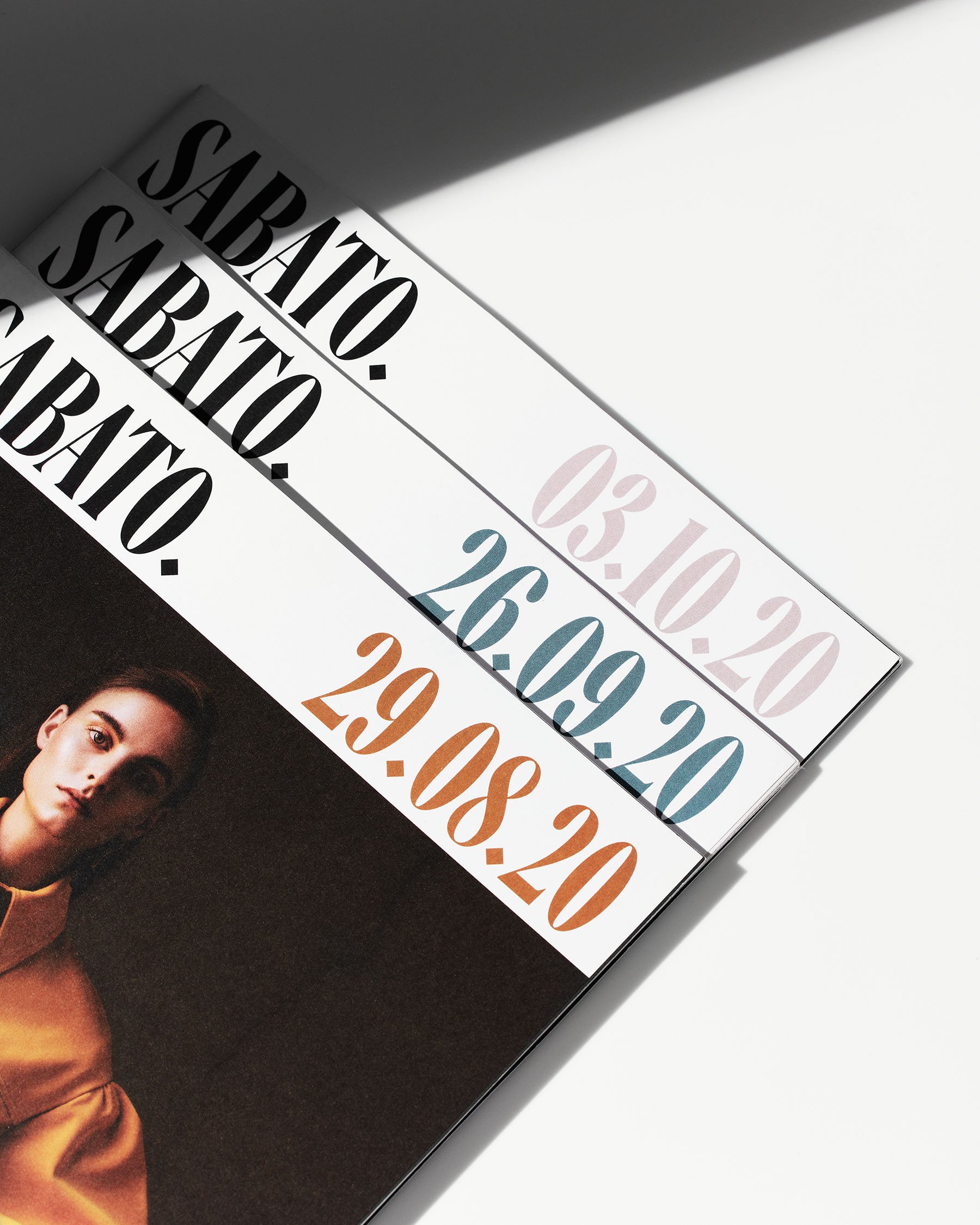

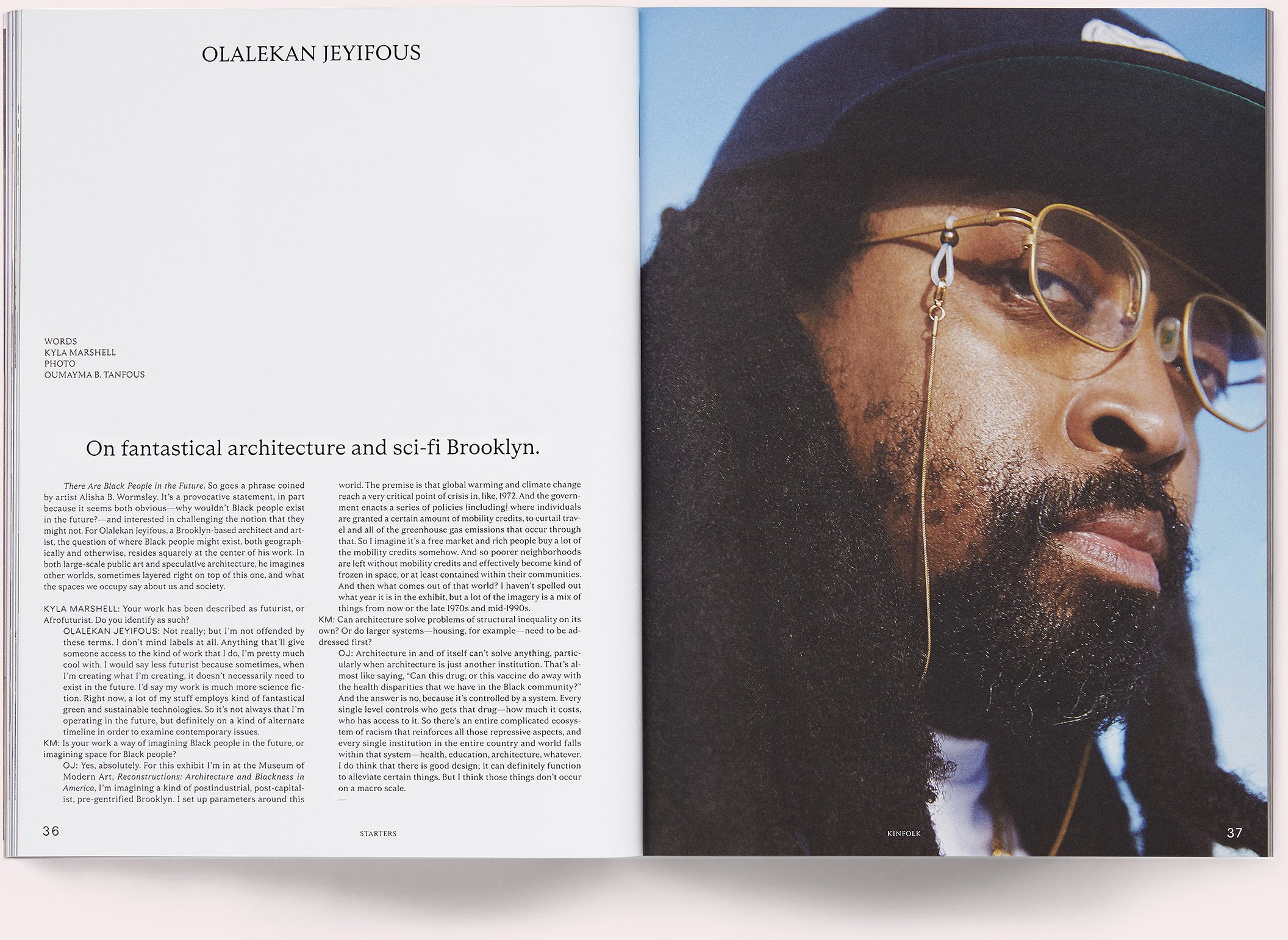

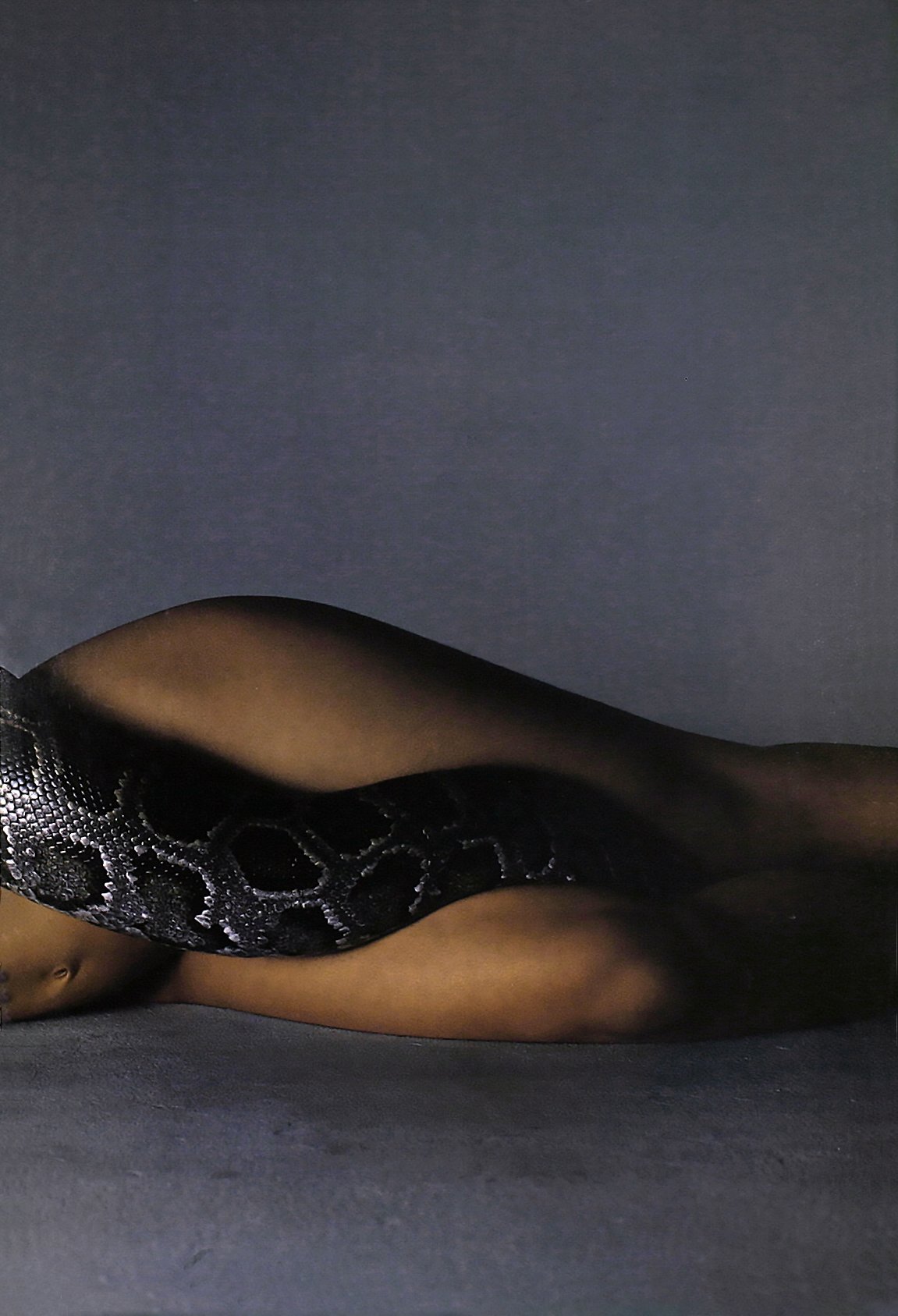

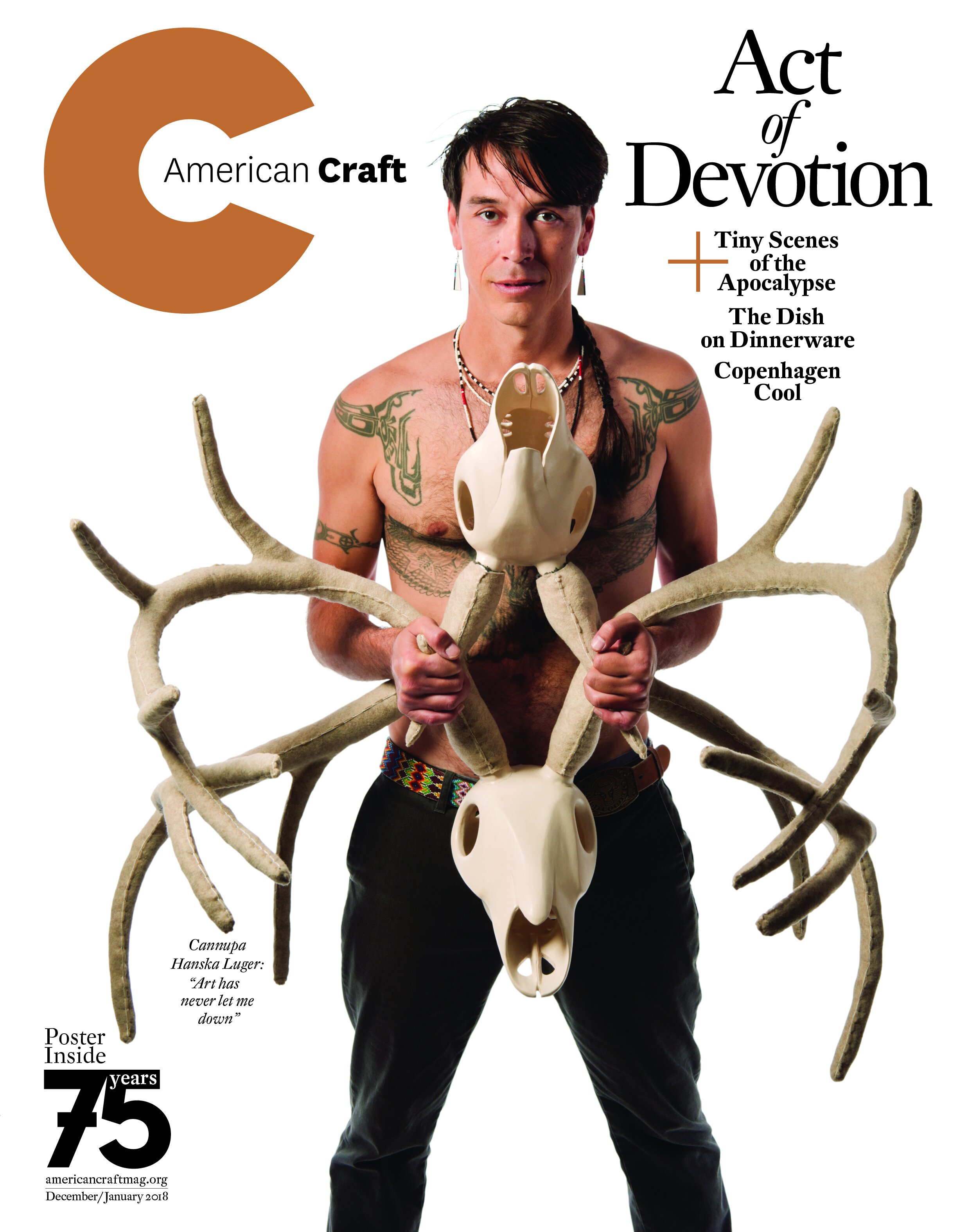

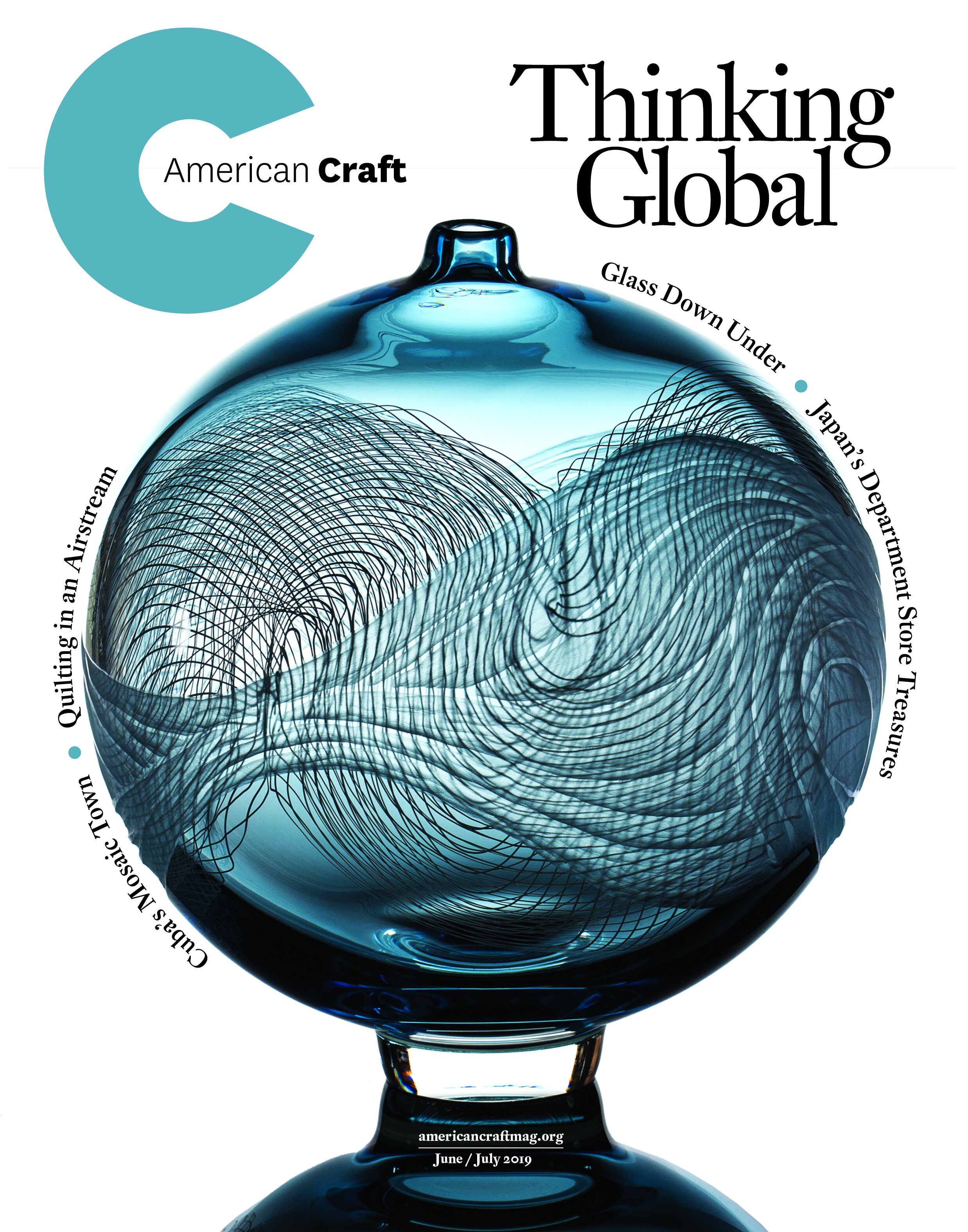

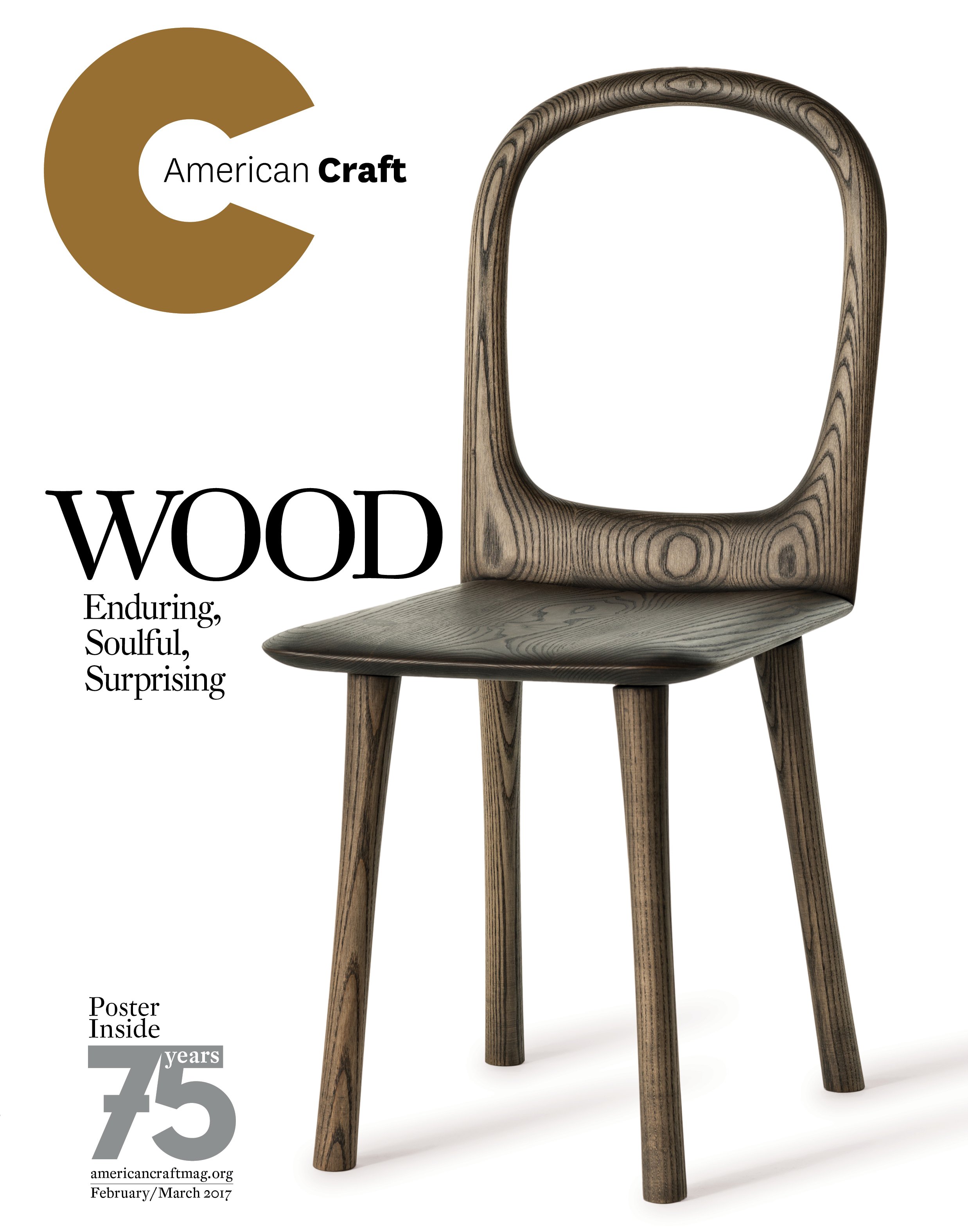

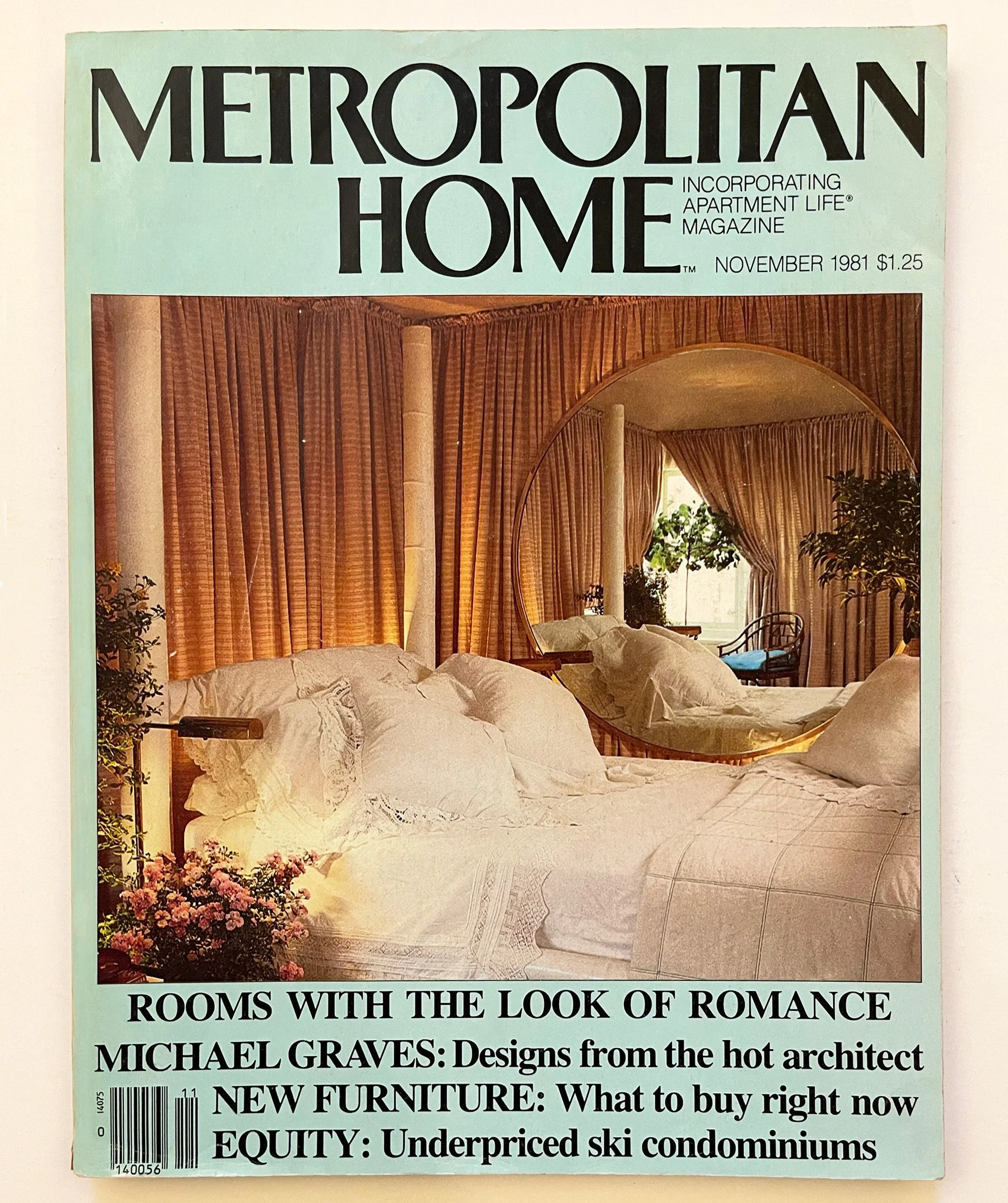

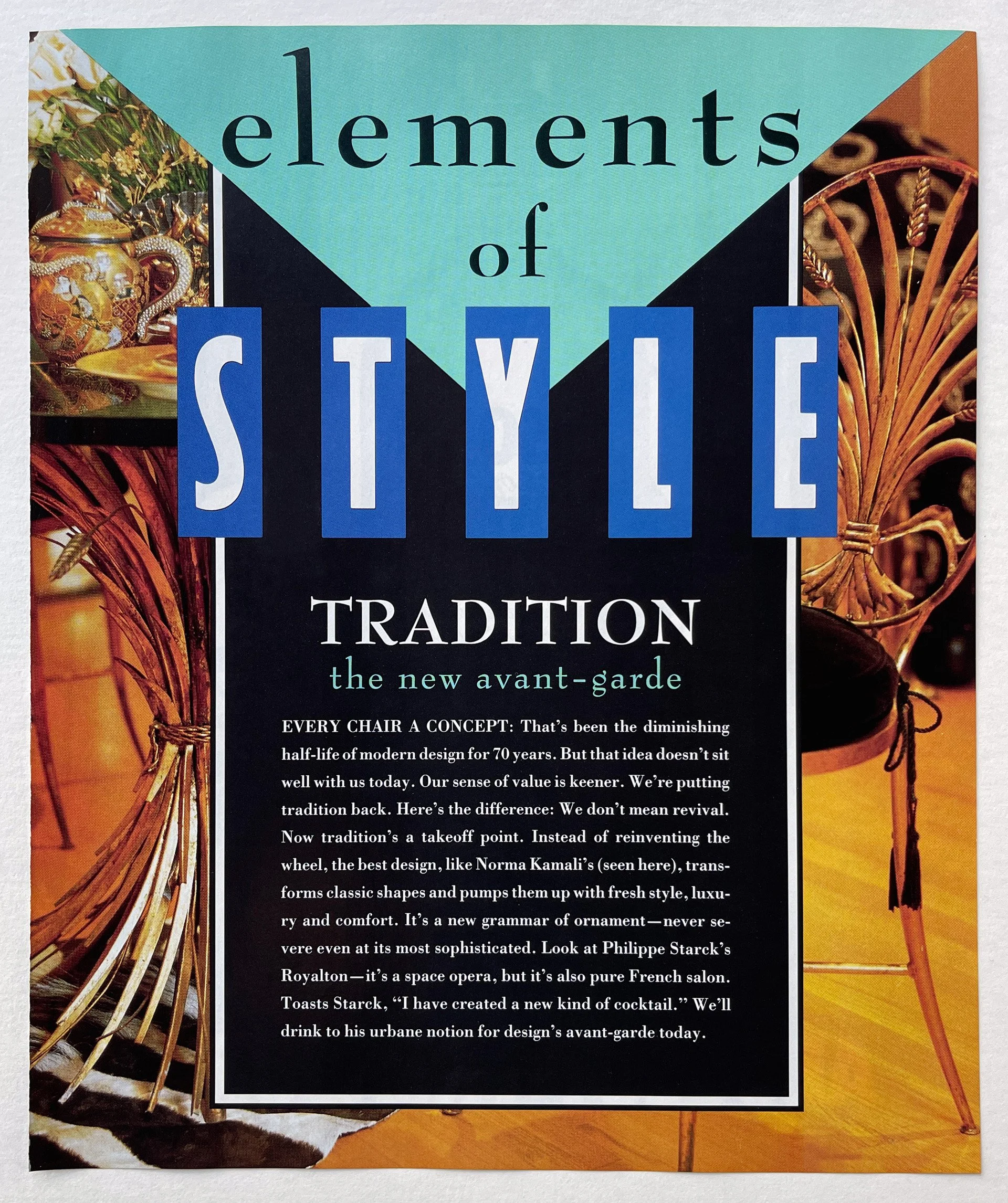

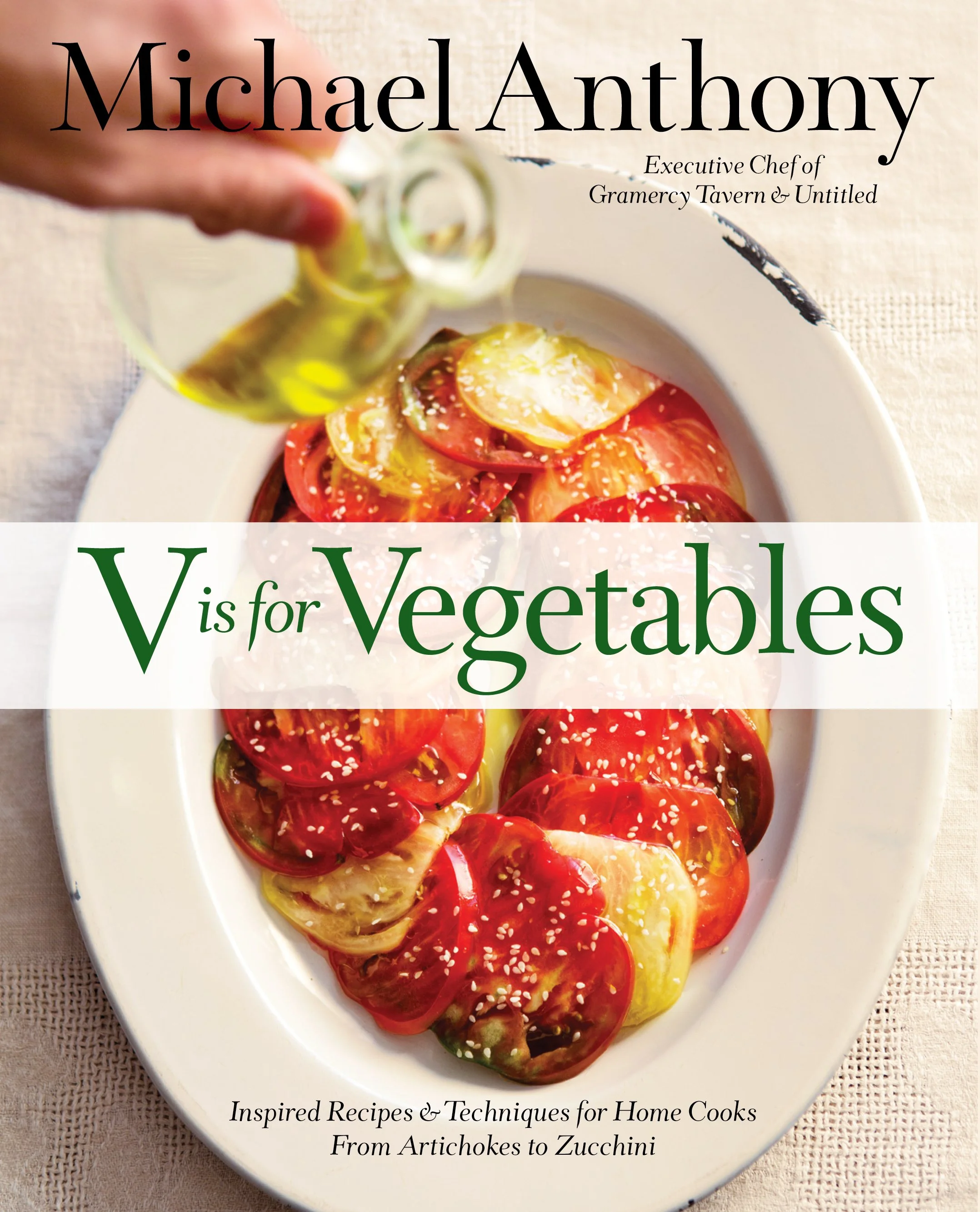

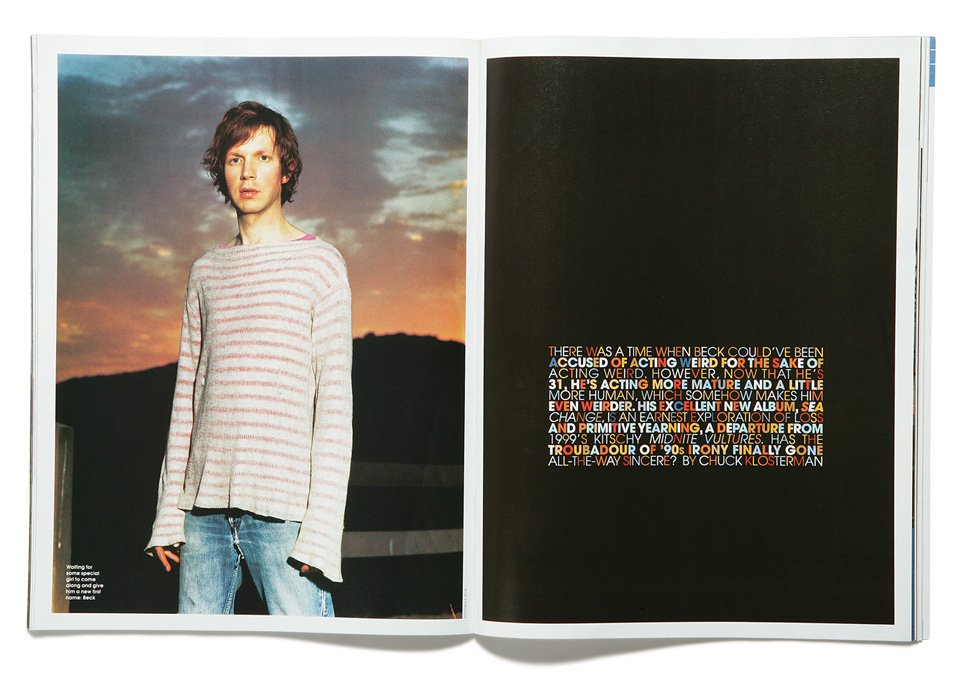

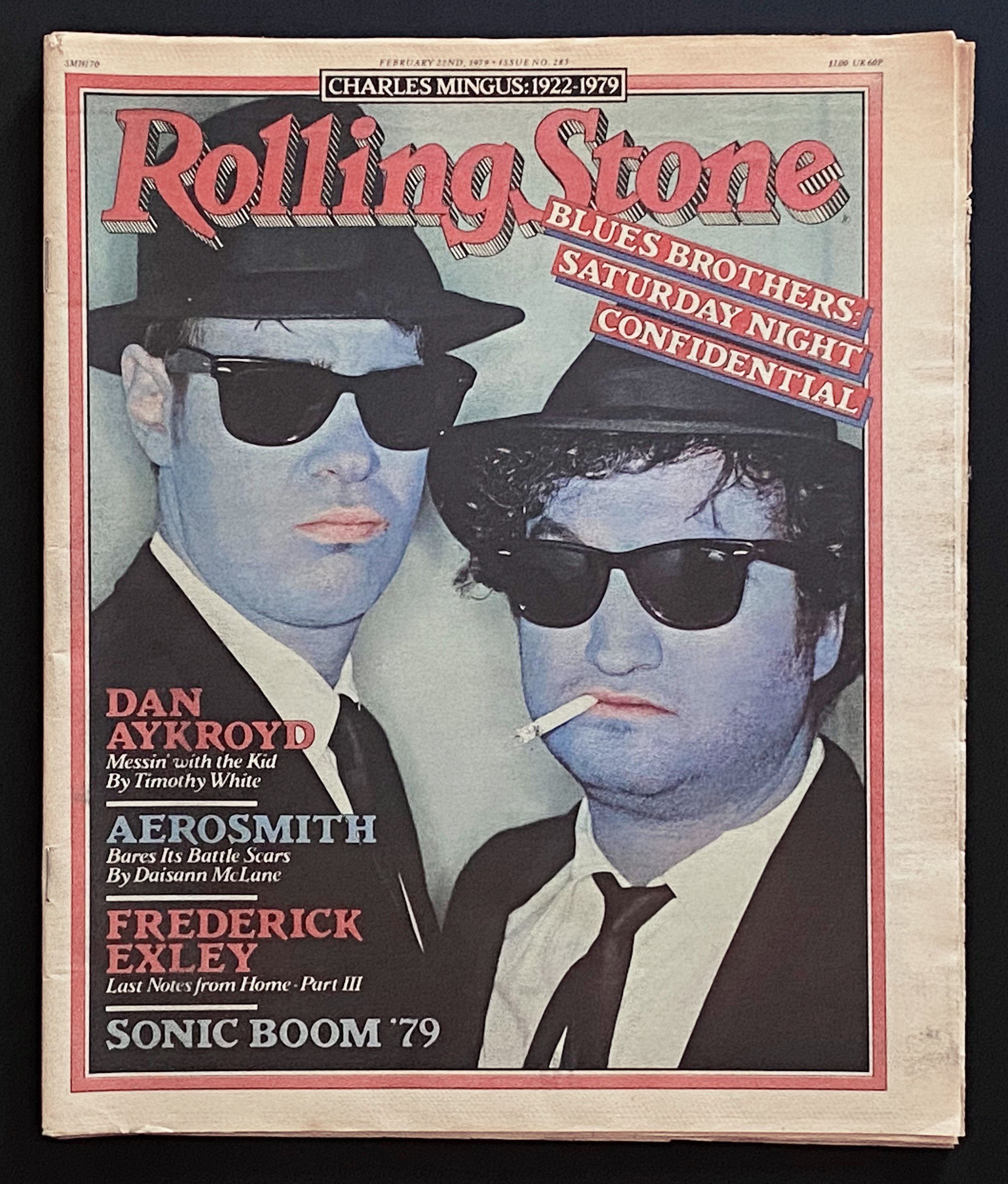

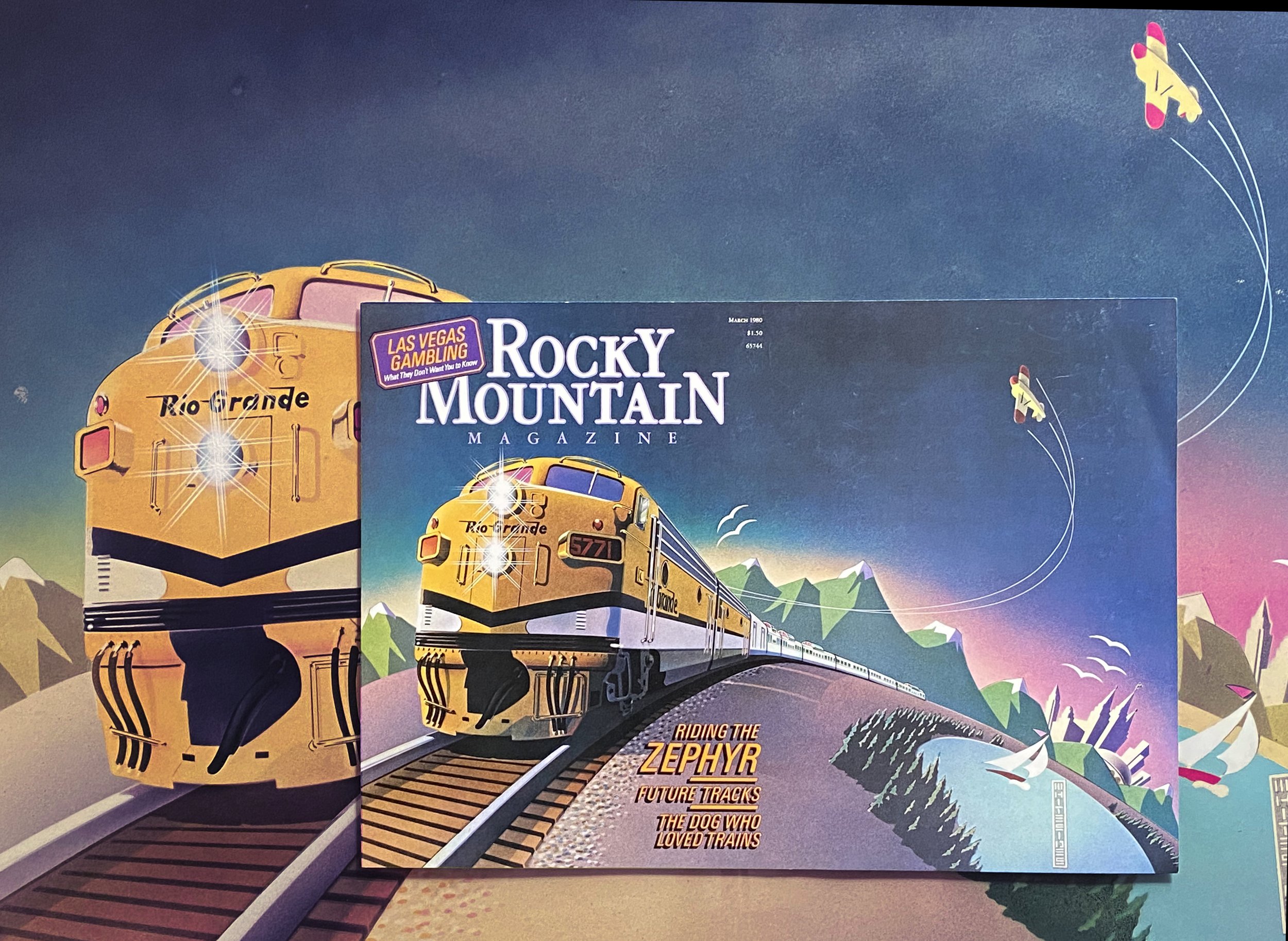

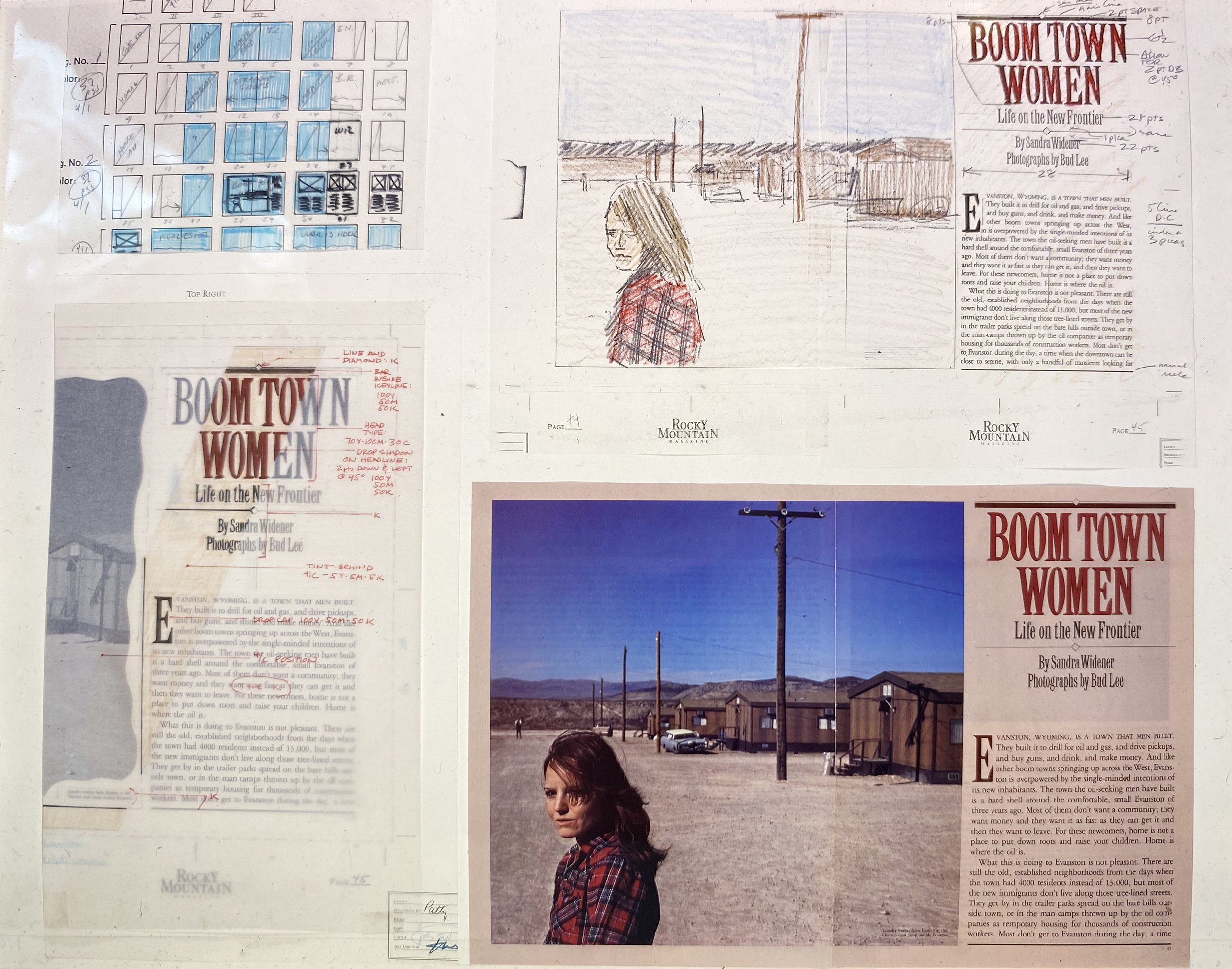

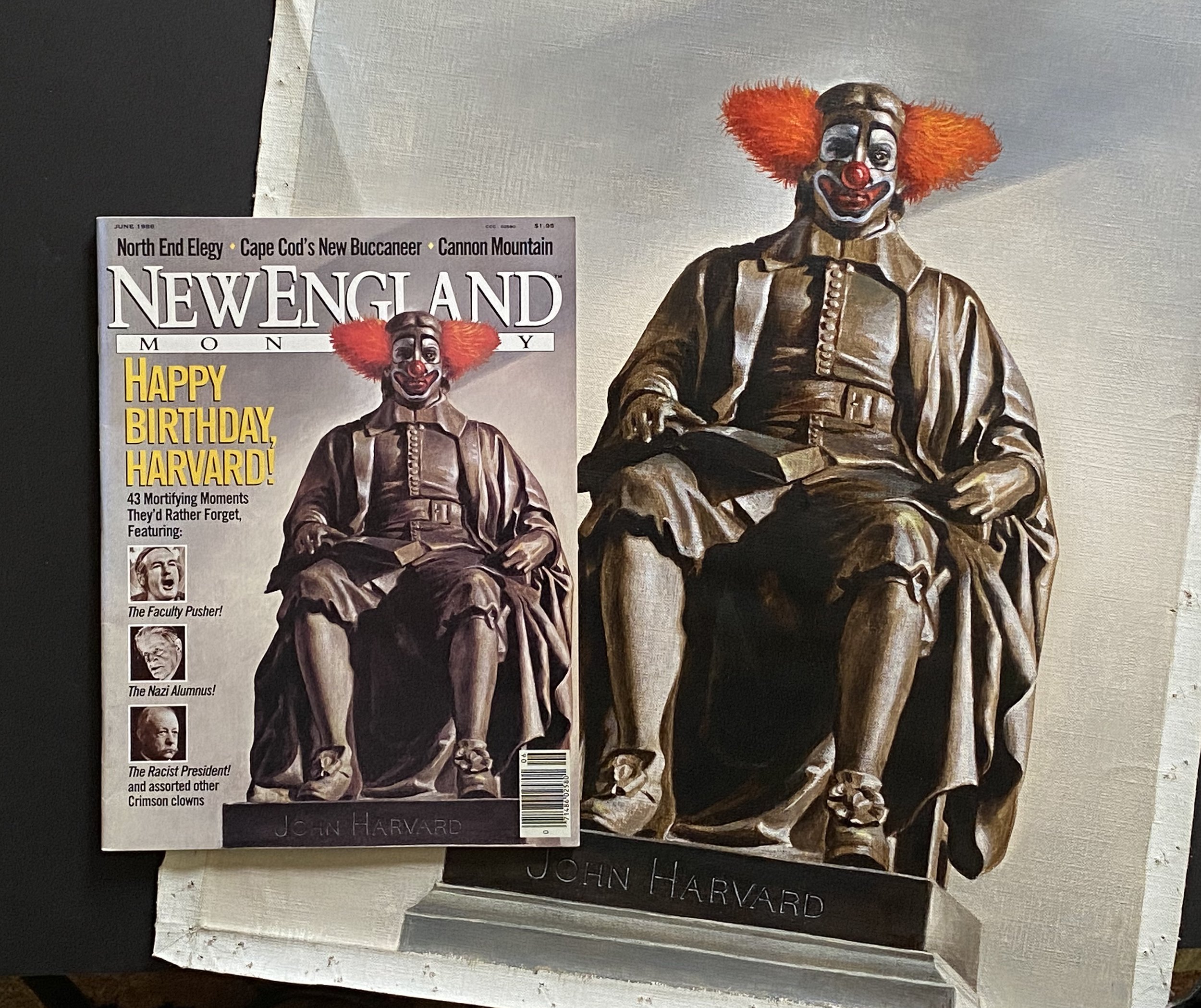

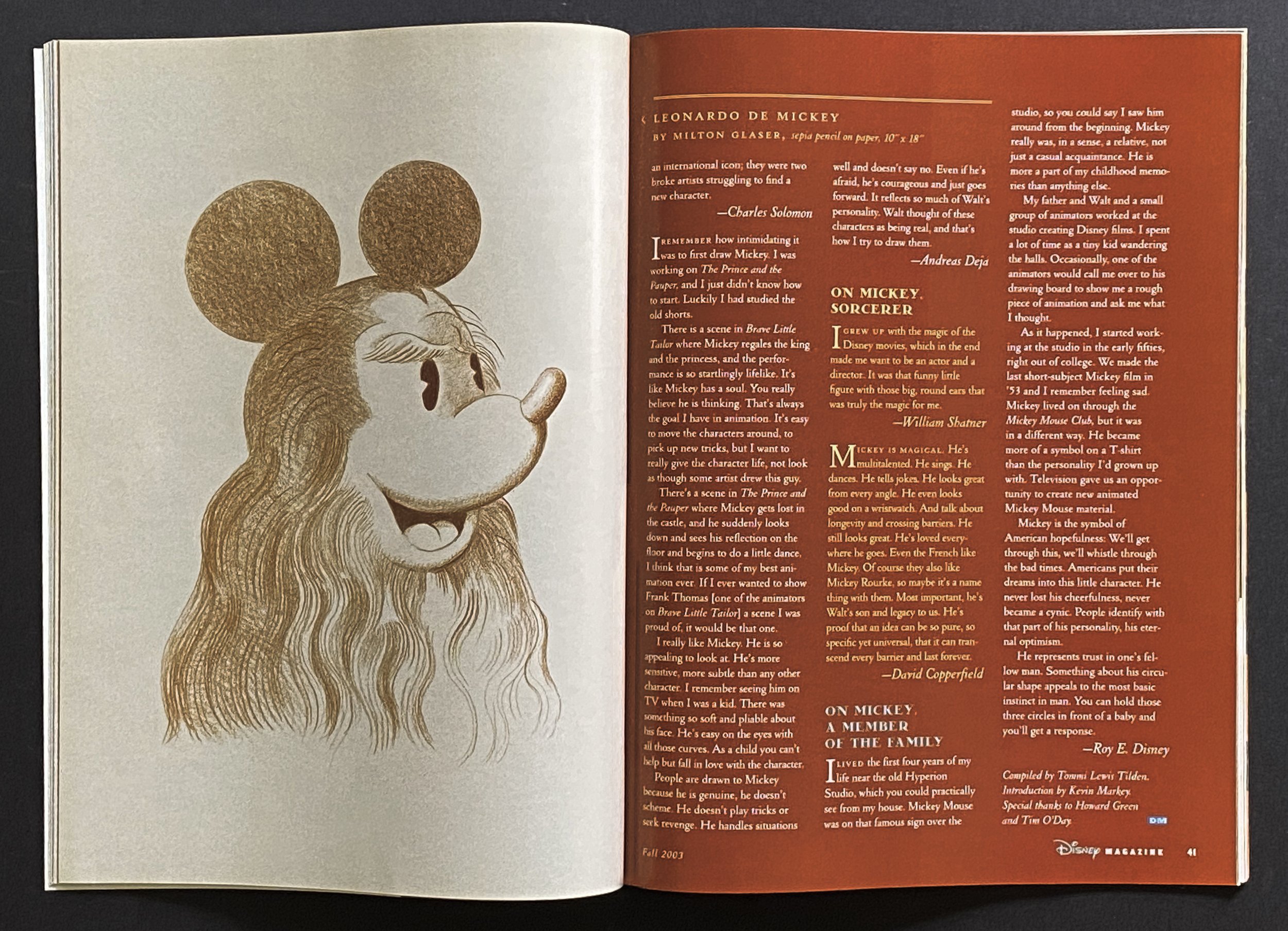

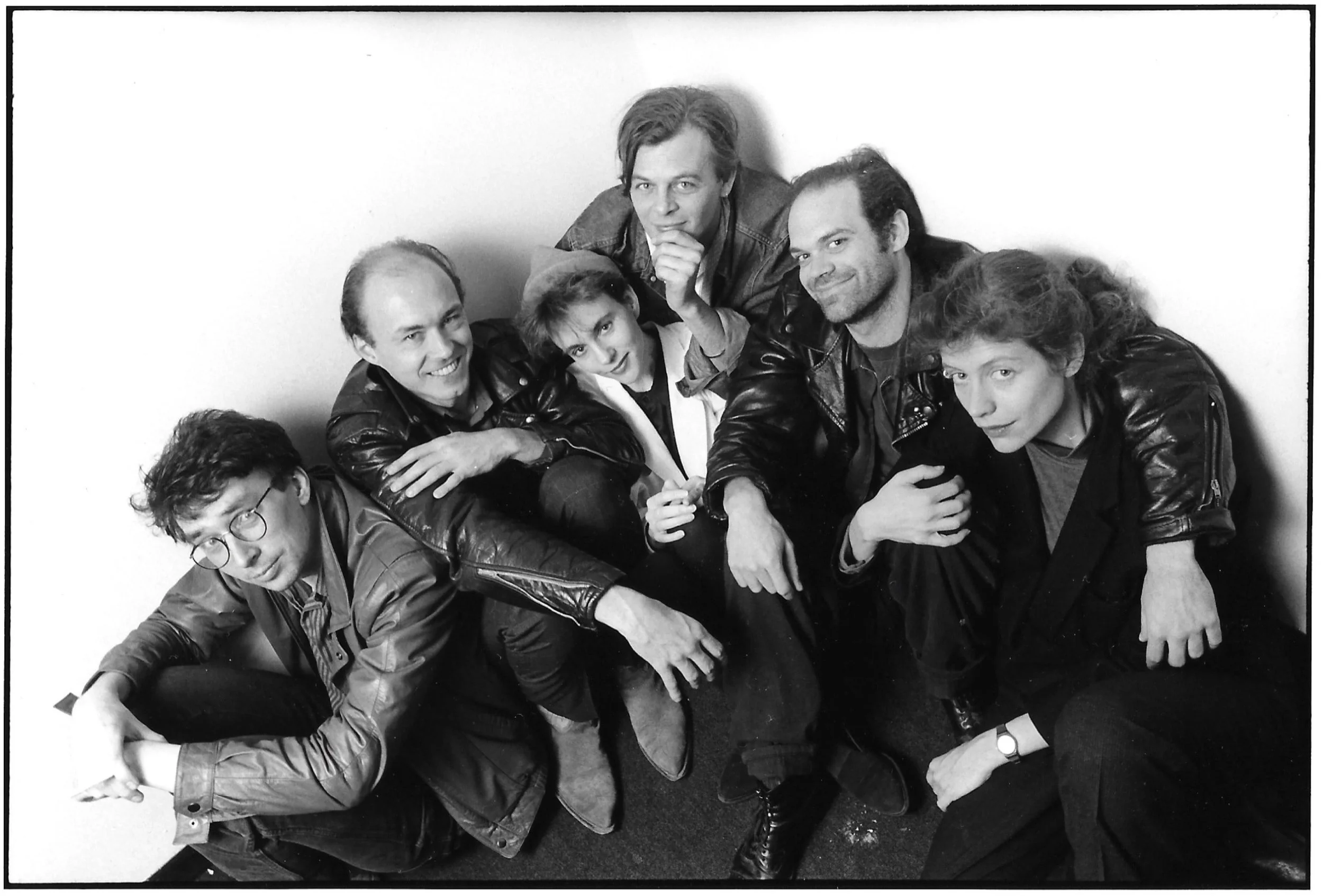

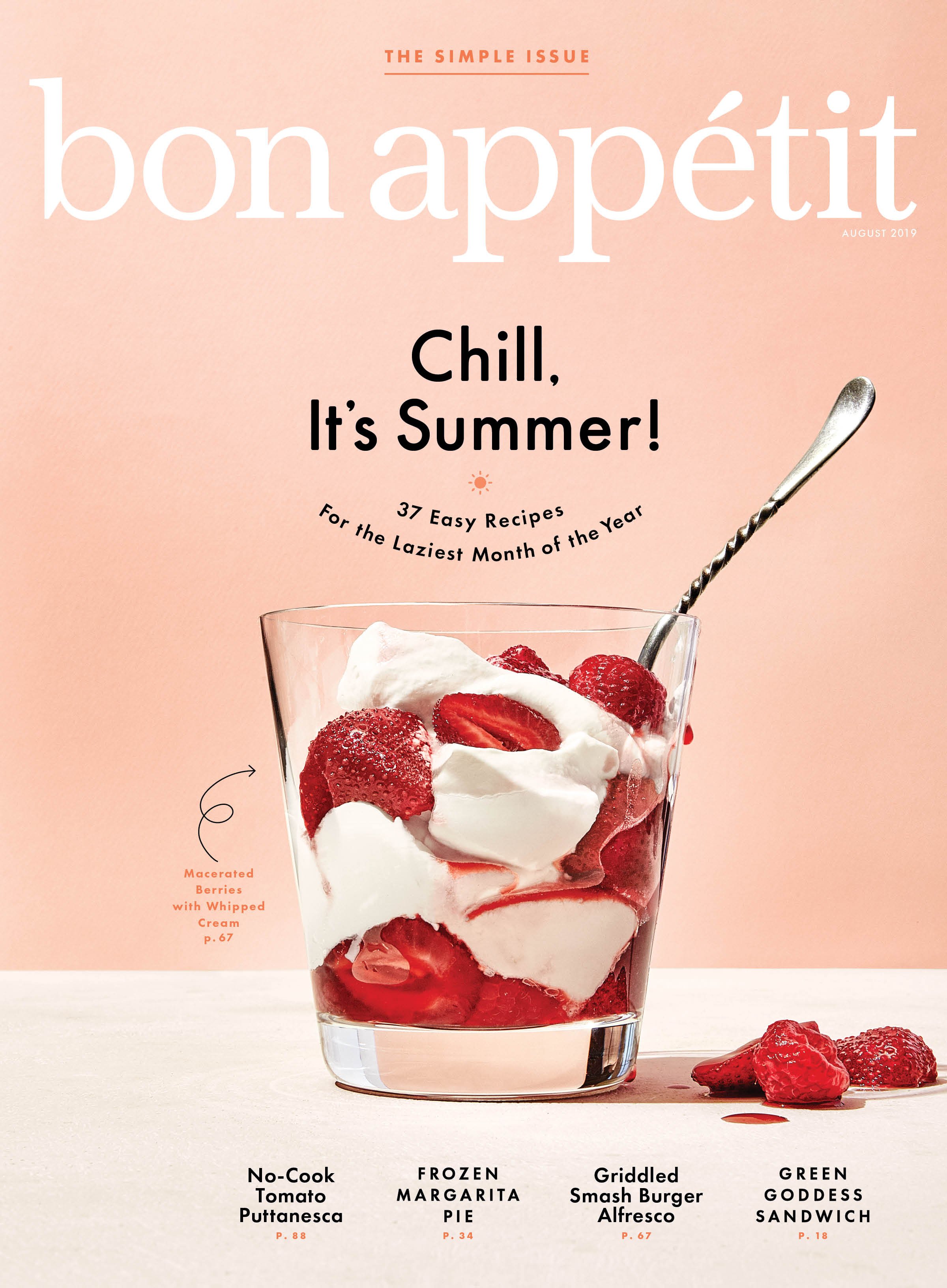

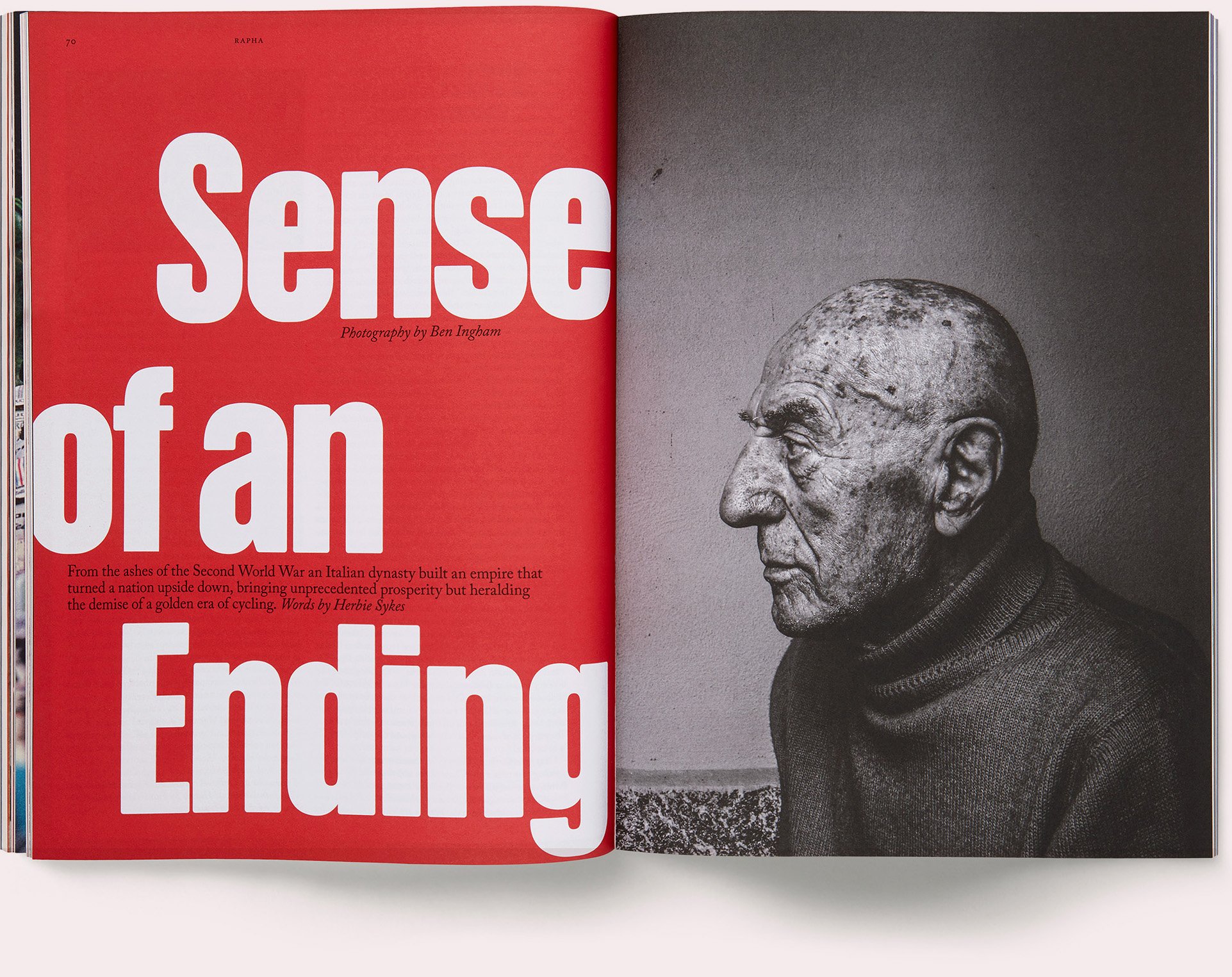

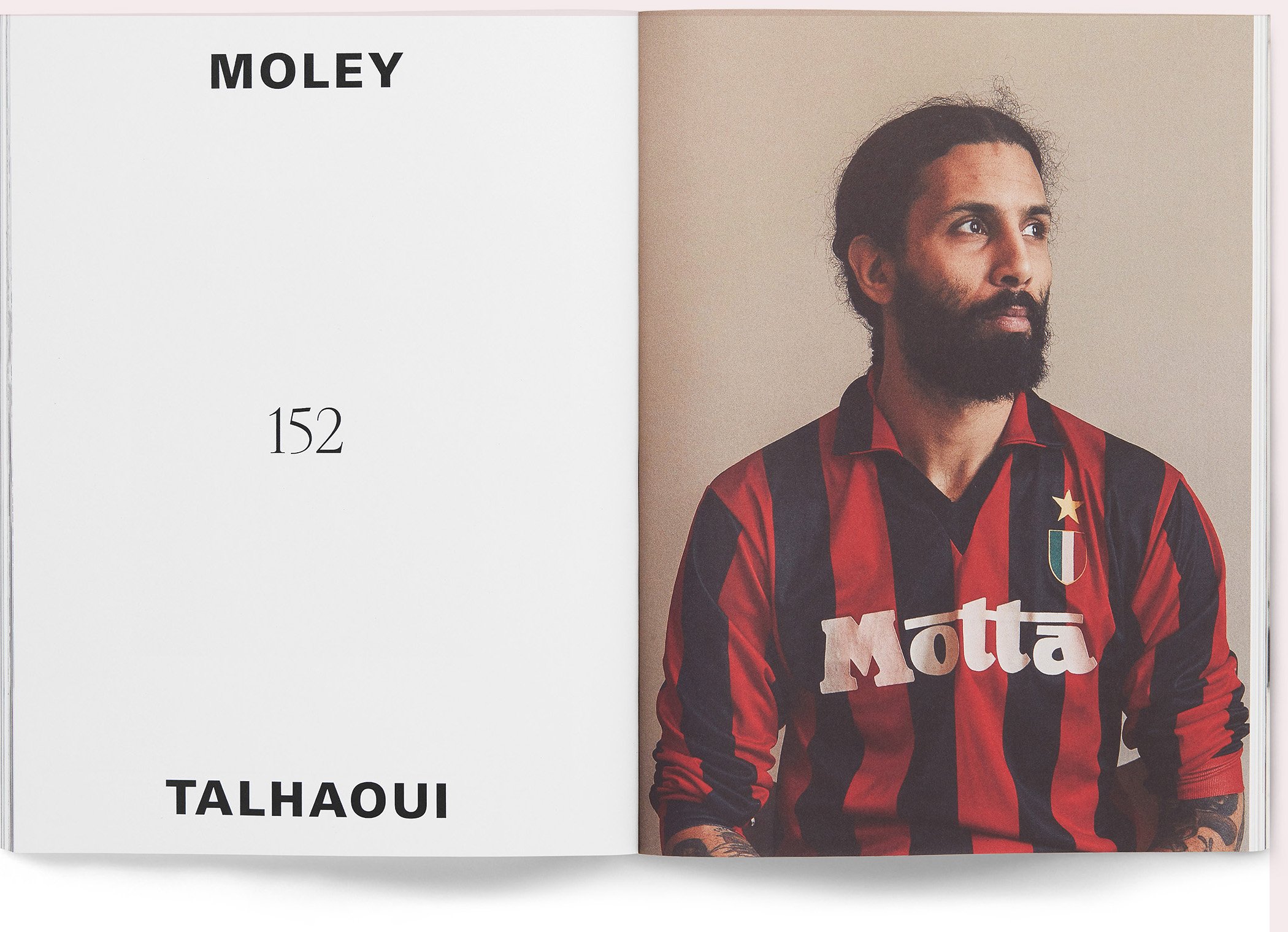

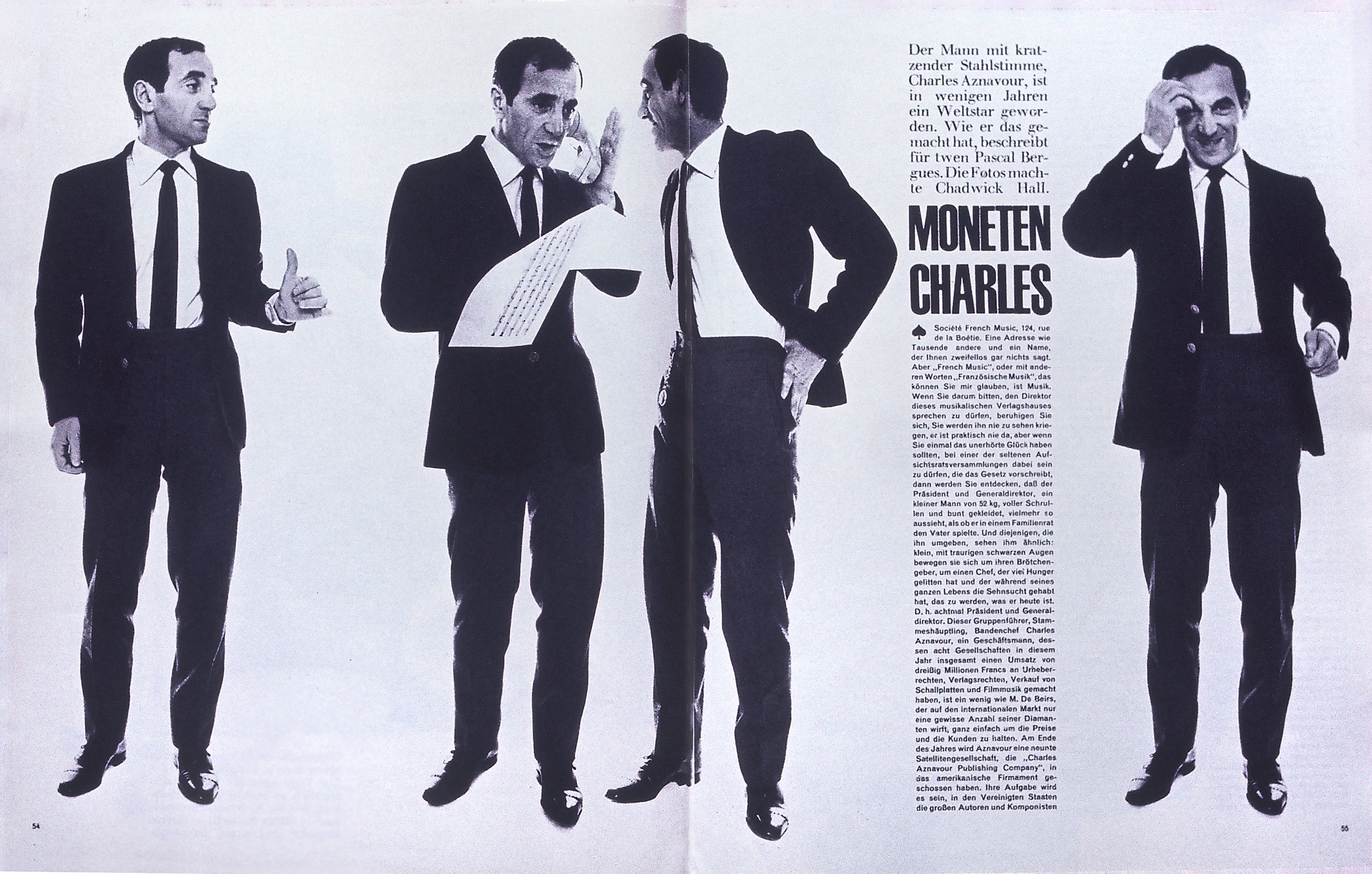

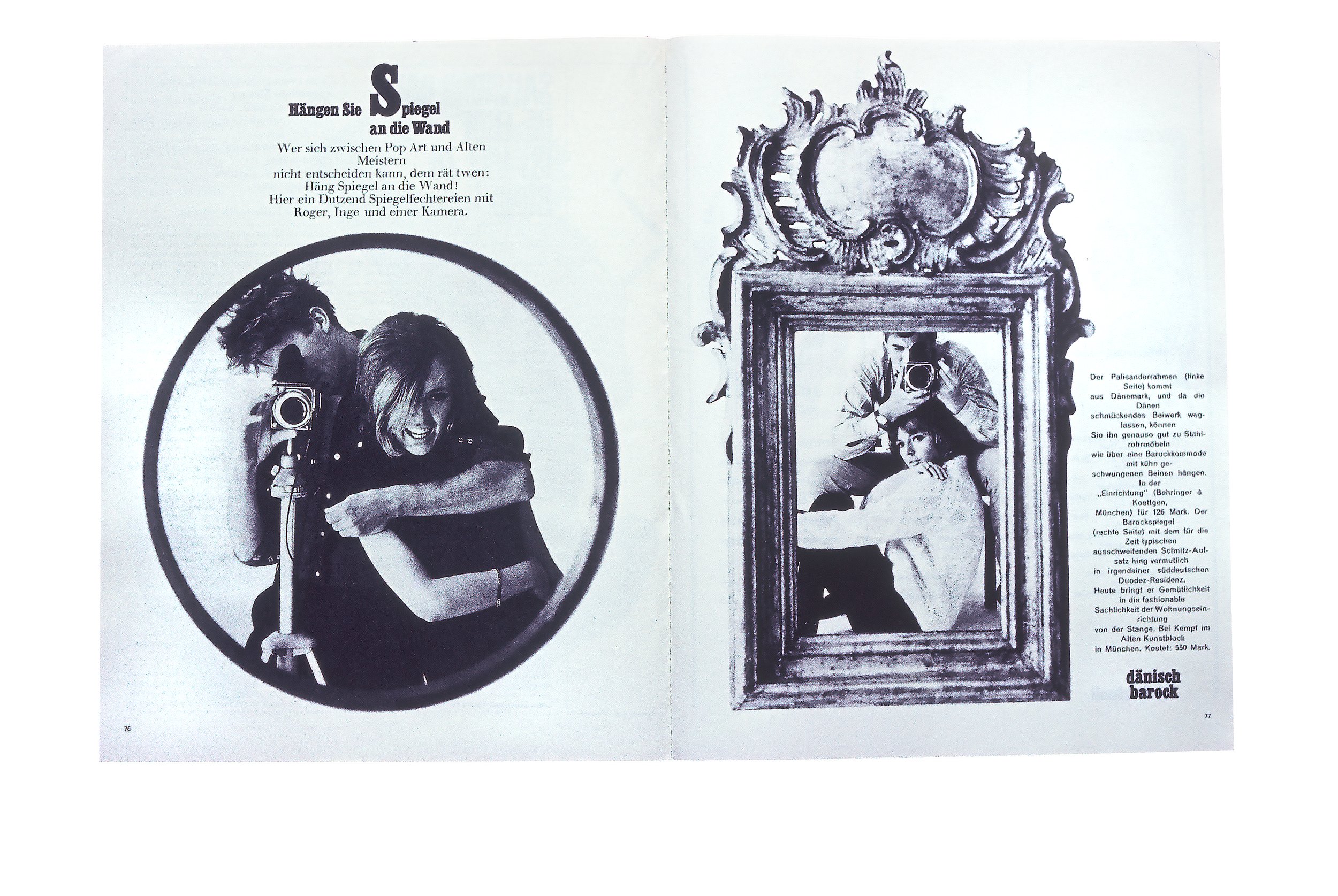

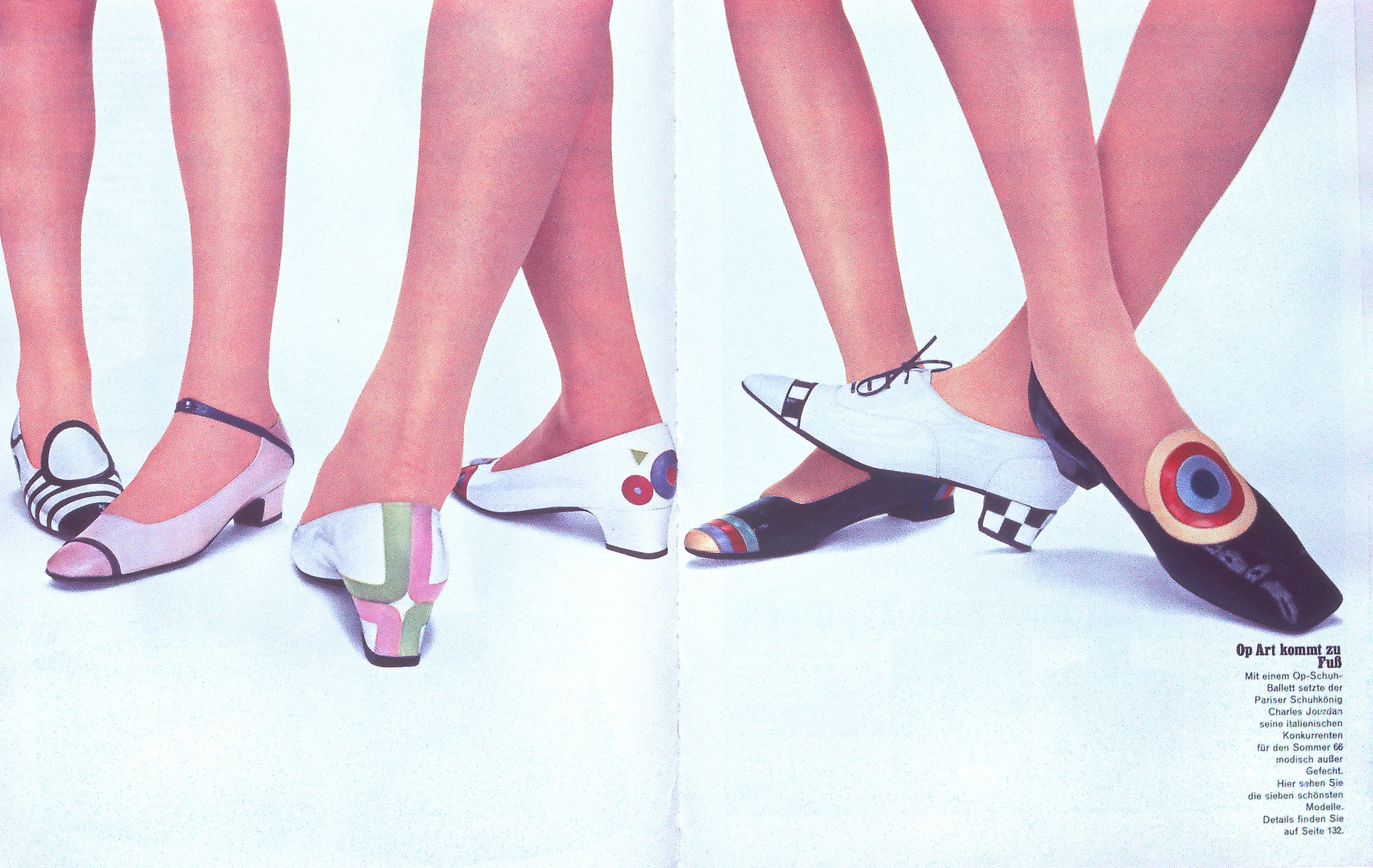

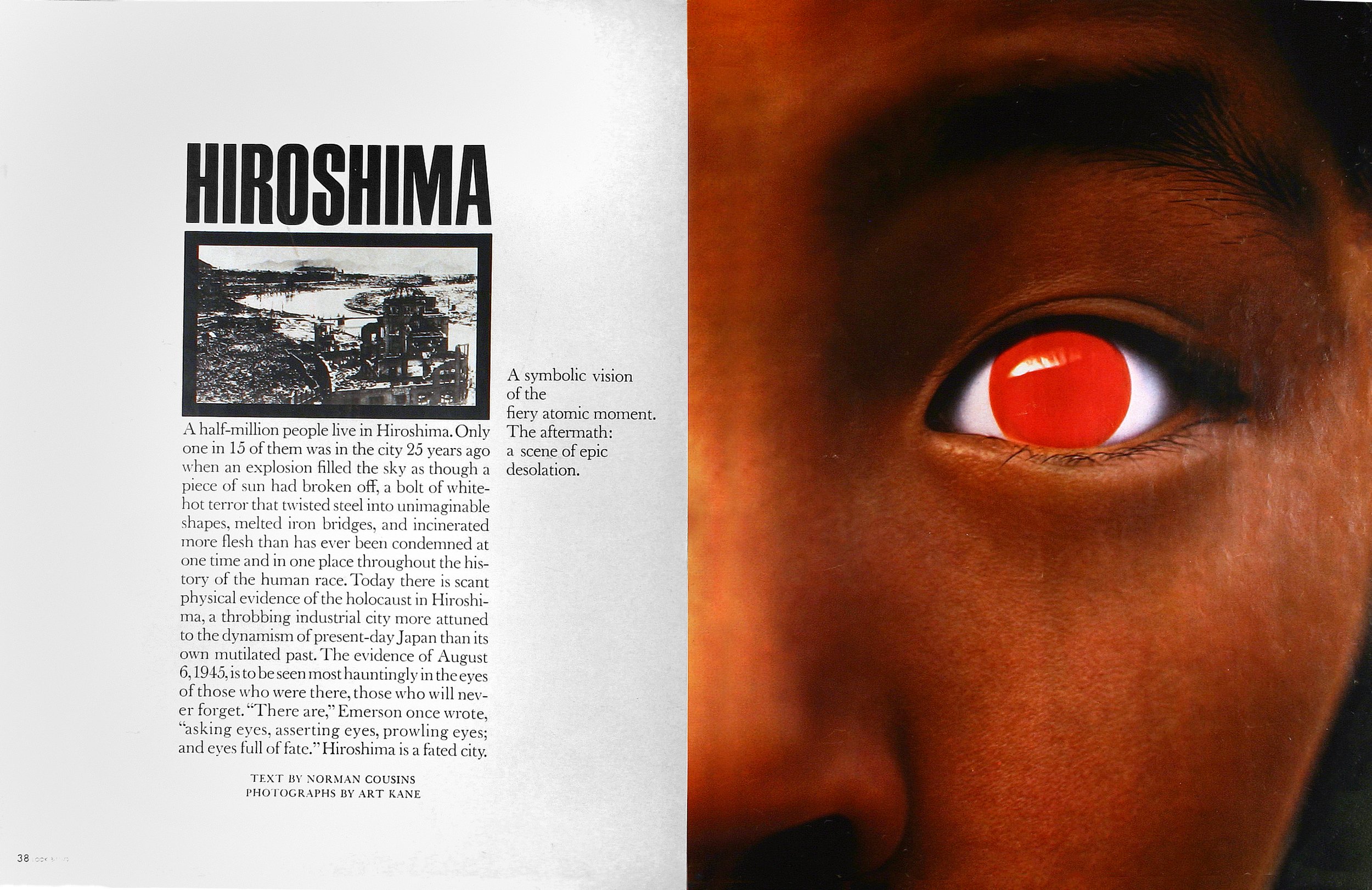

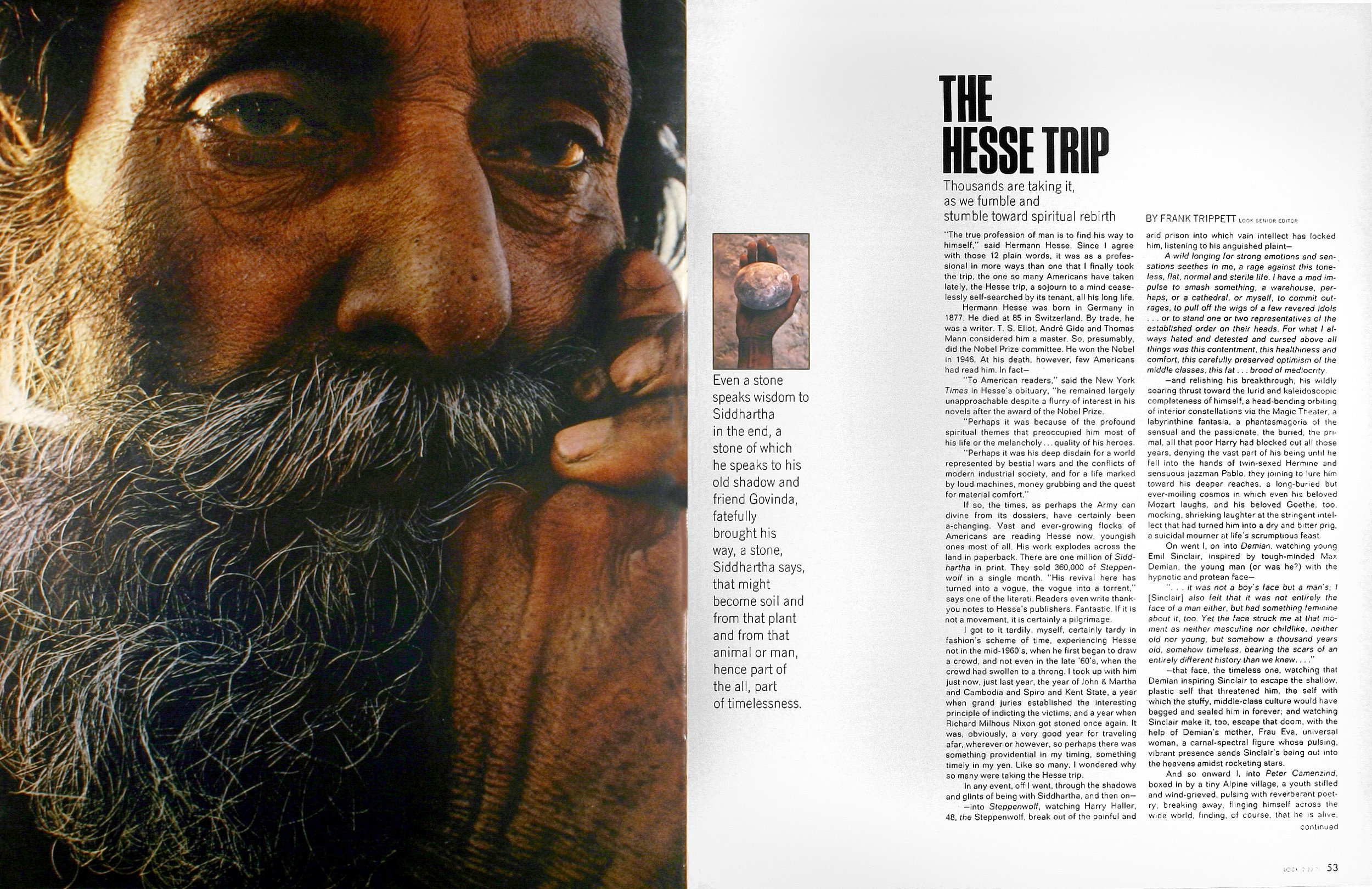

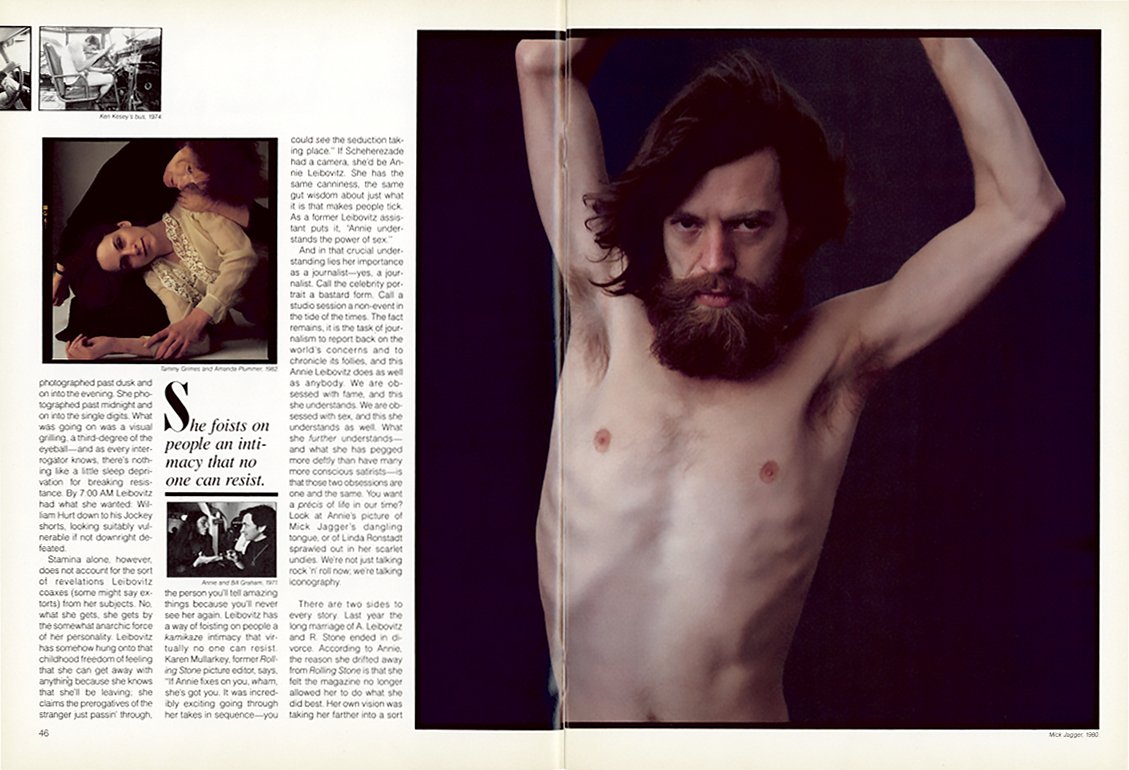

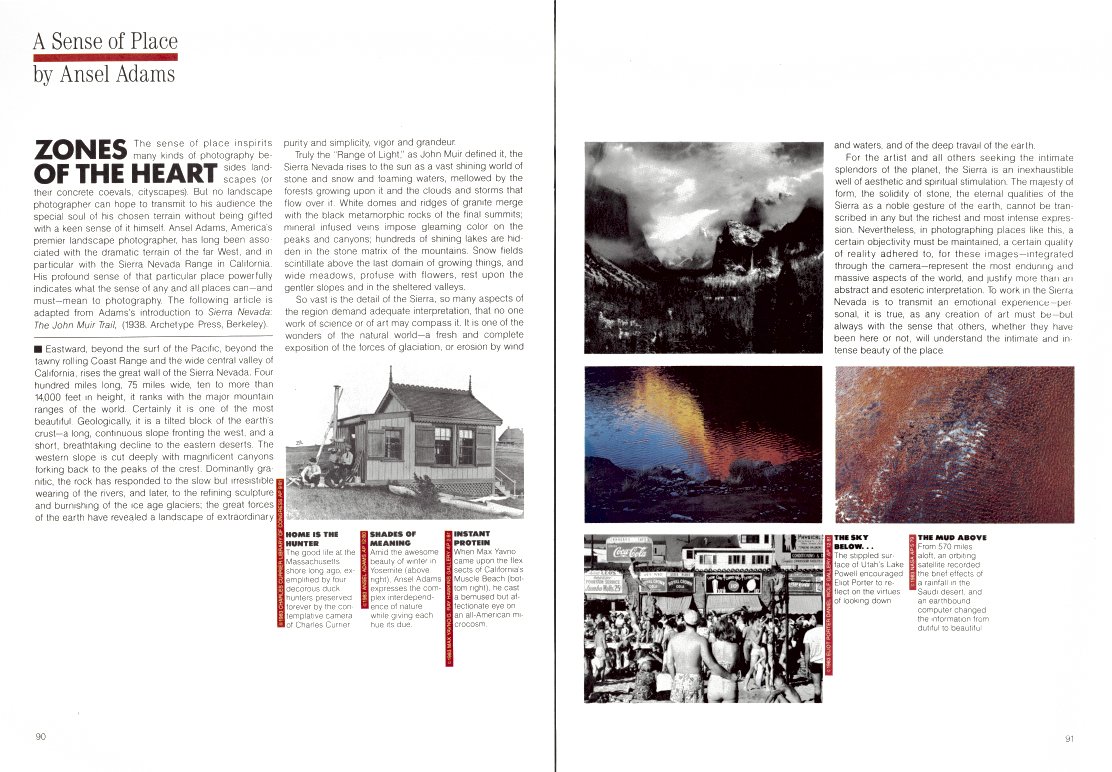

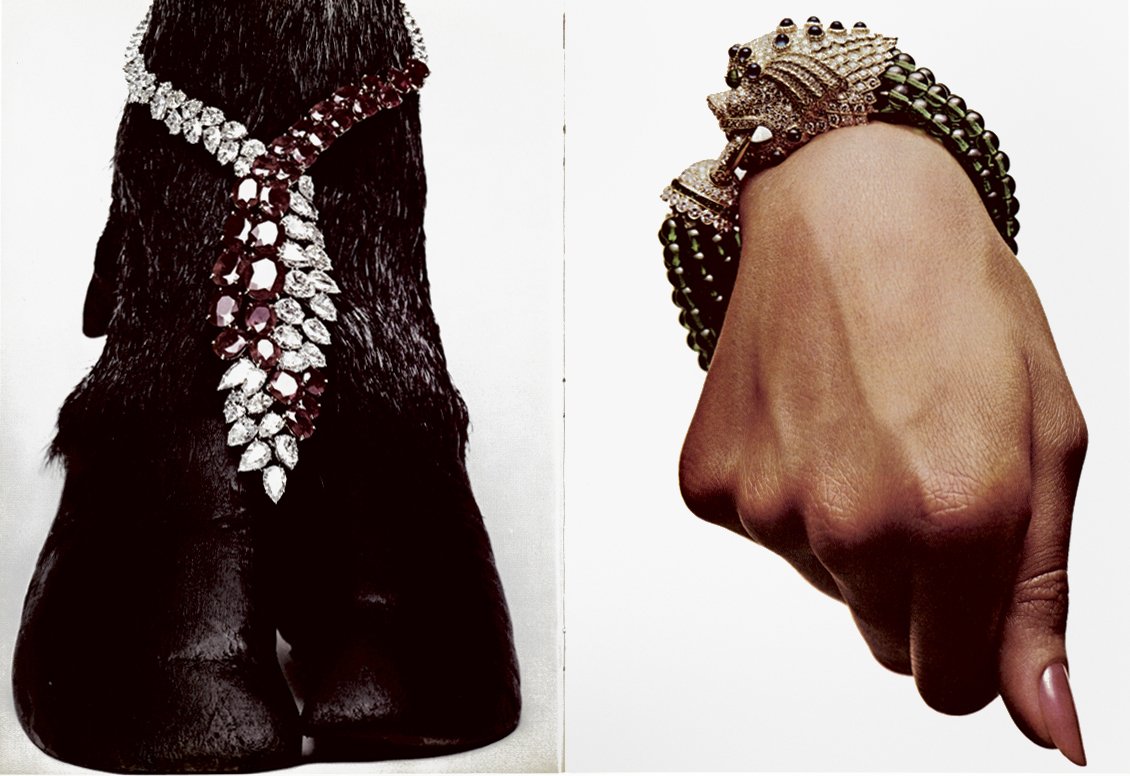

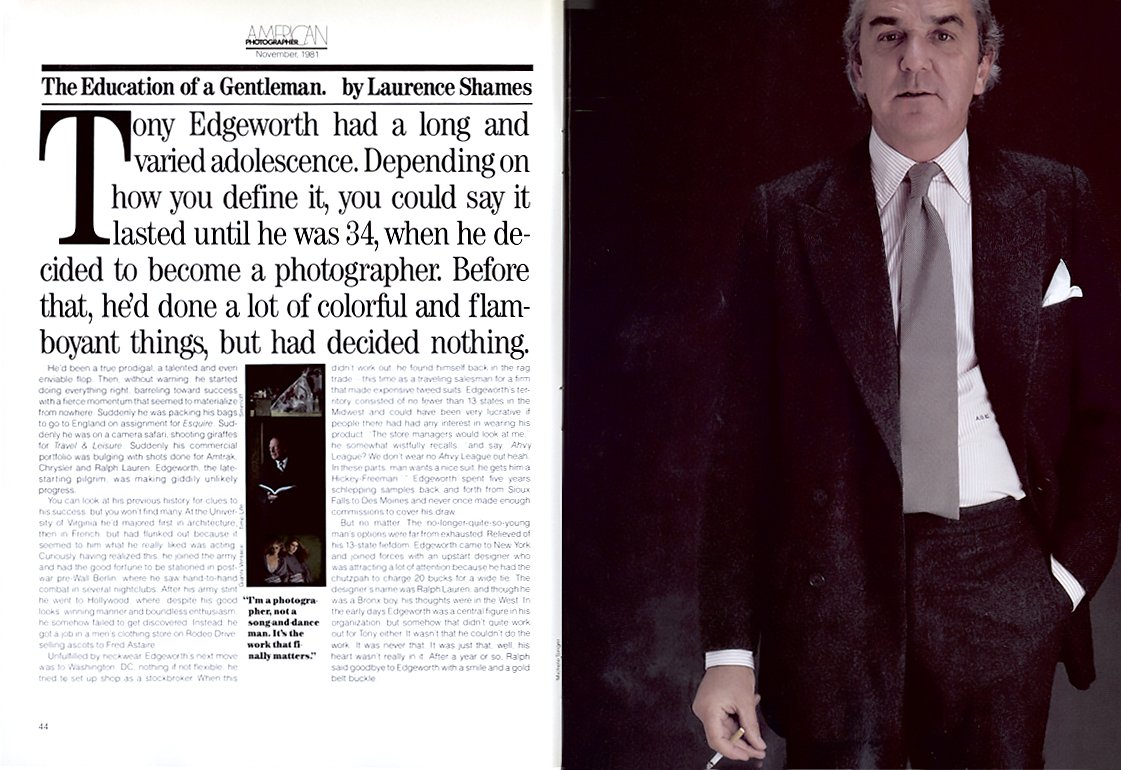

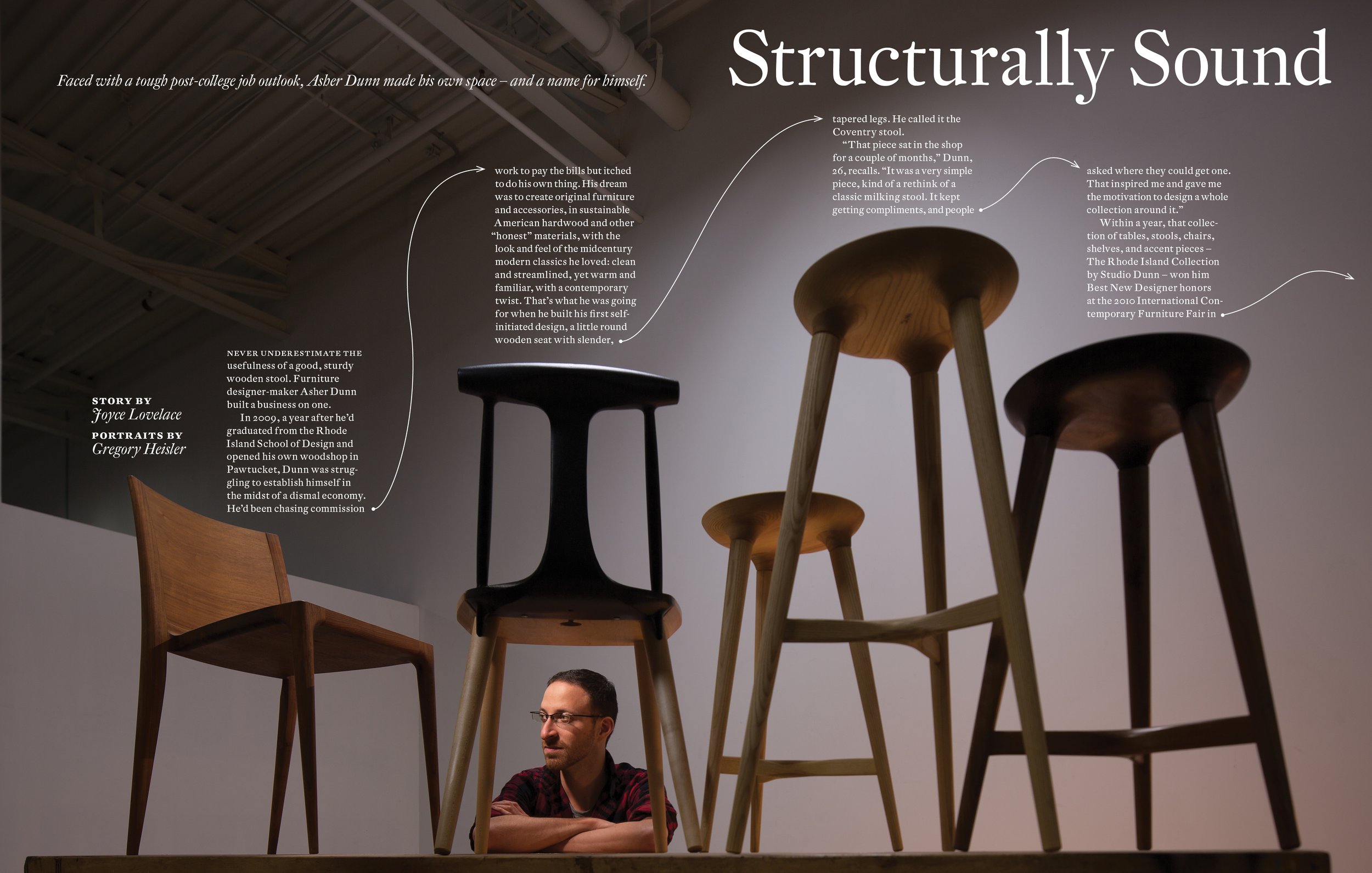

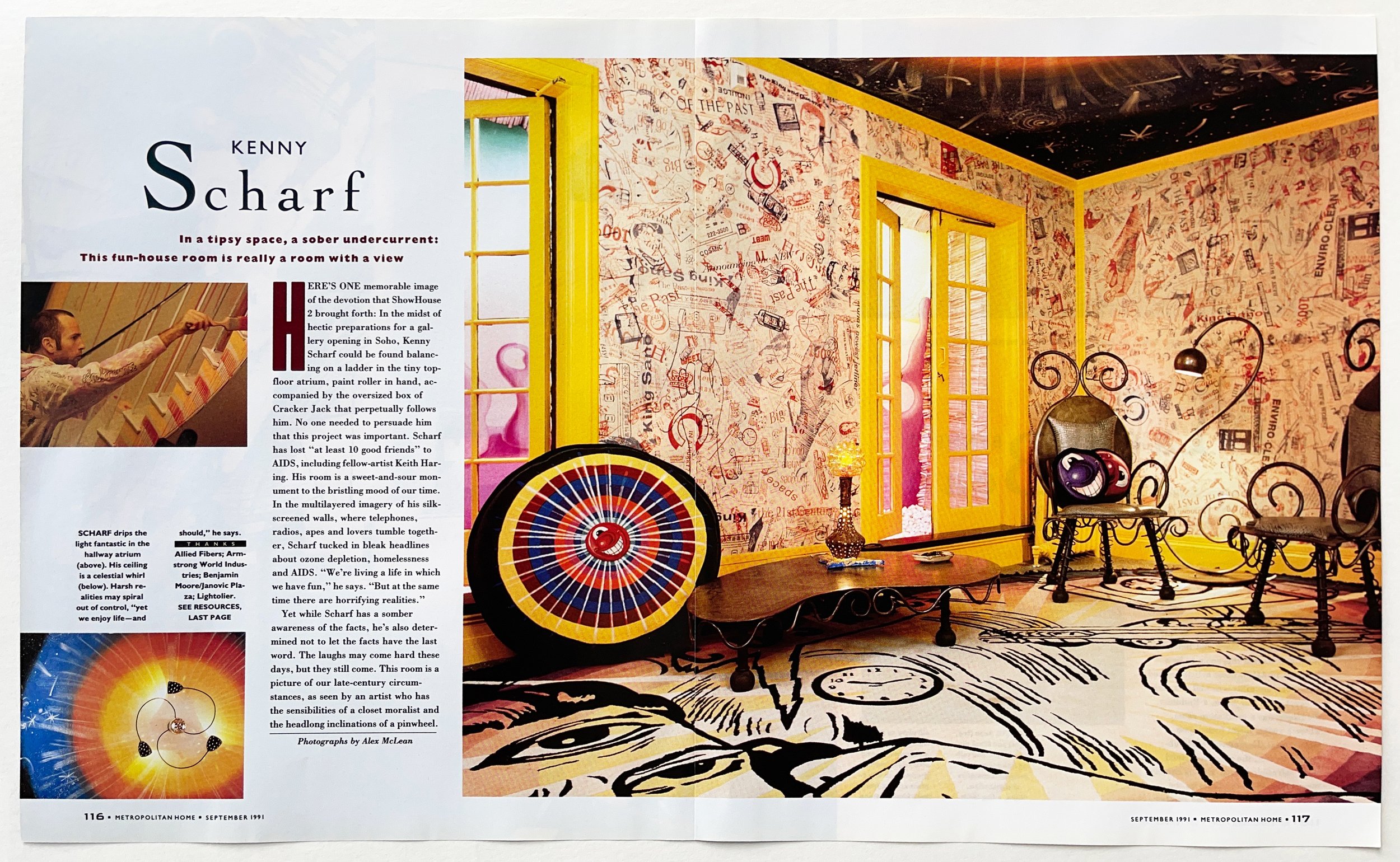

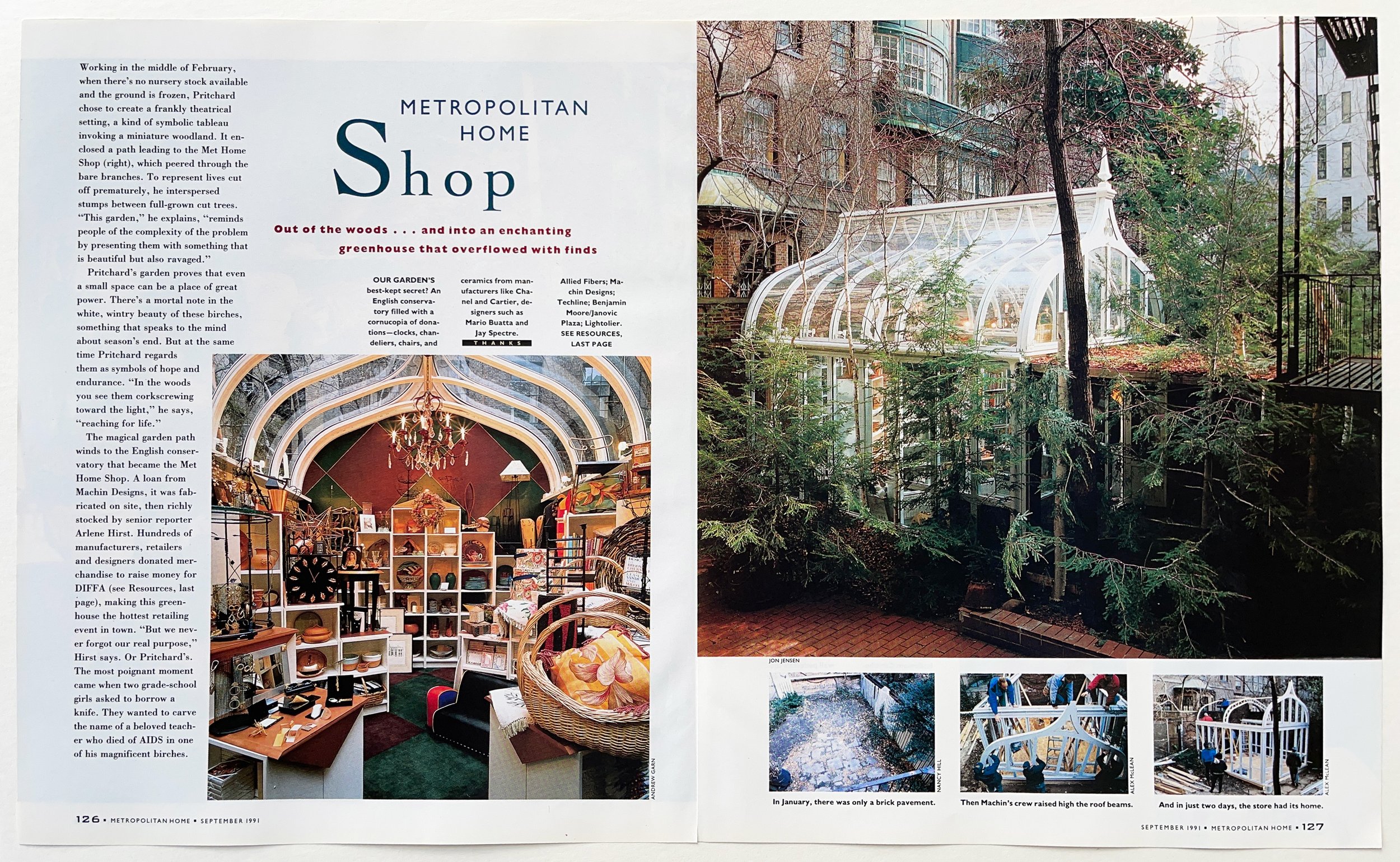

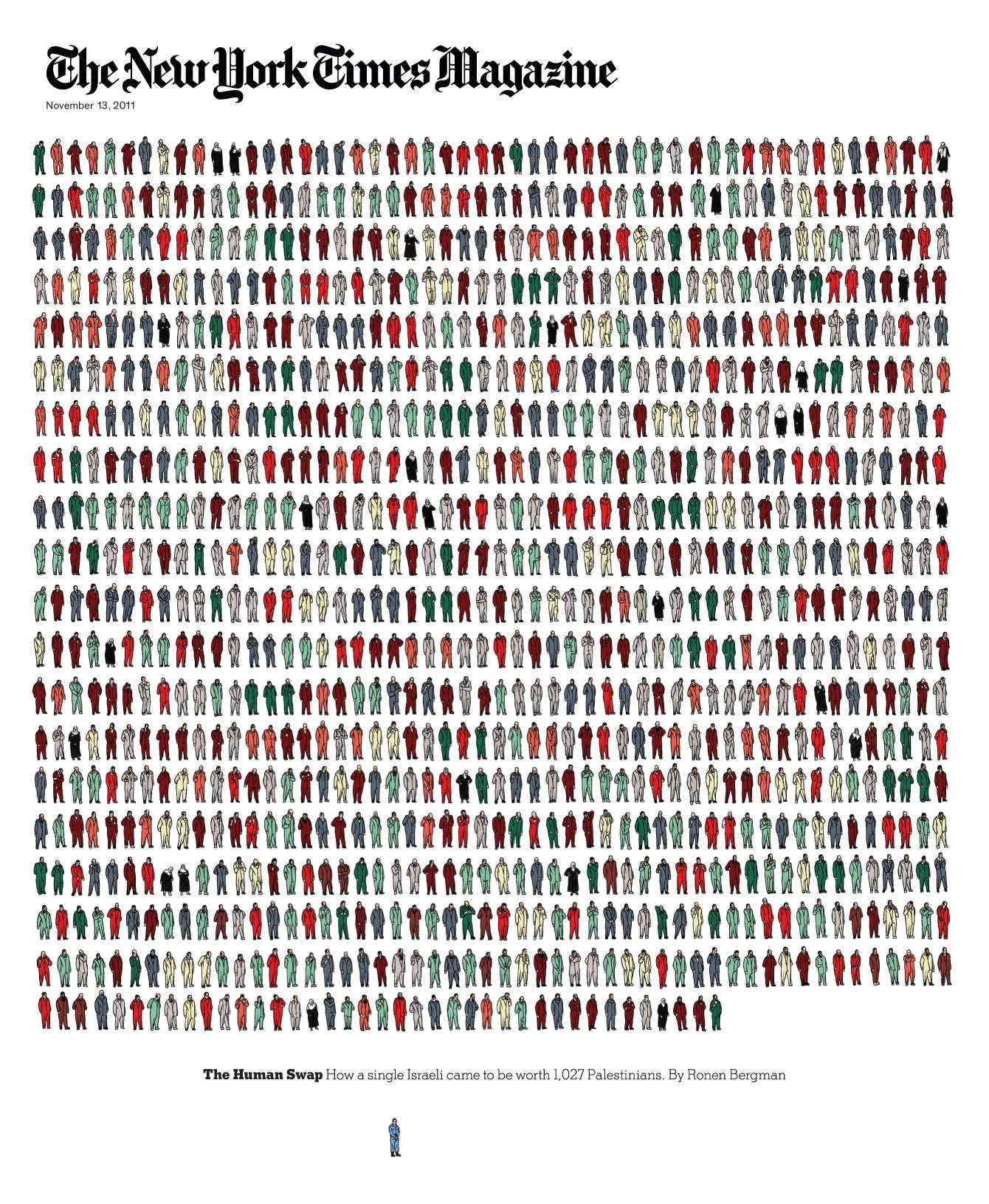

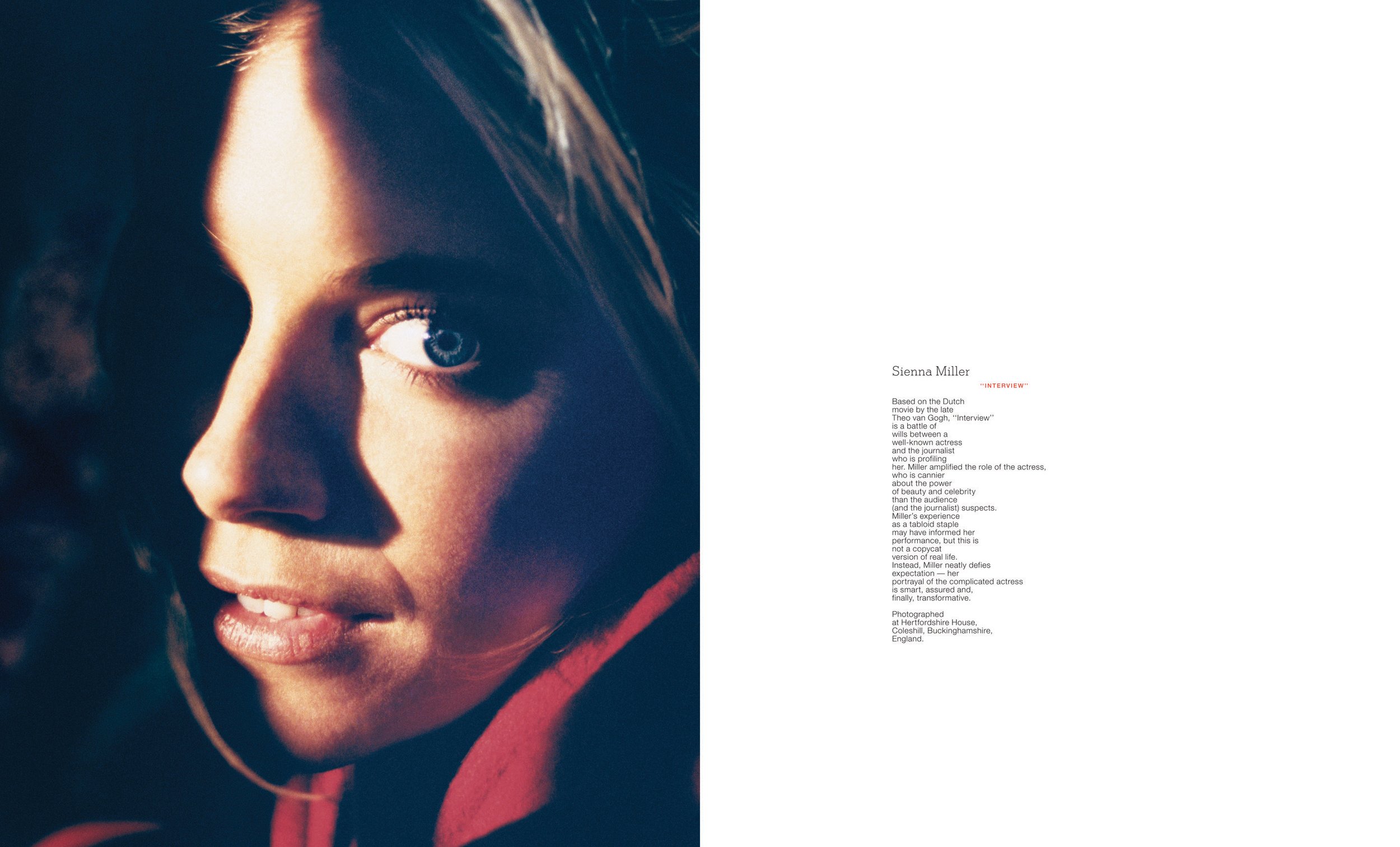

When Scott met Plat. The first of Dadich’s many collaborations with photographer Platon

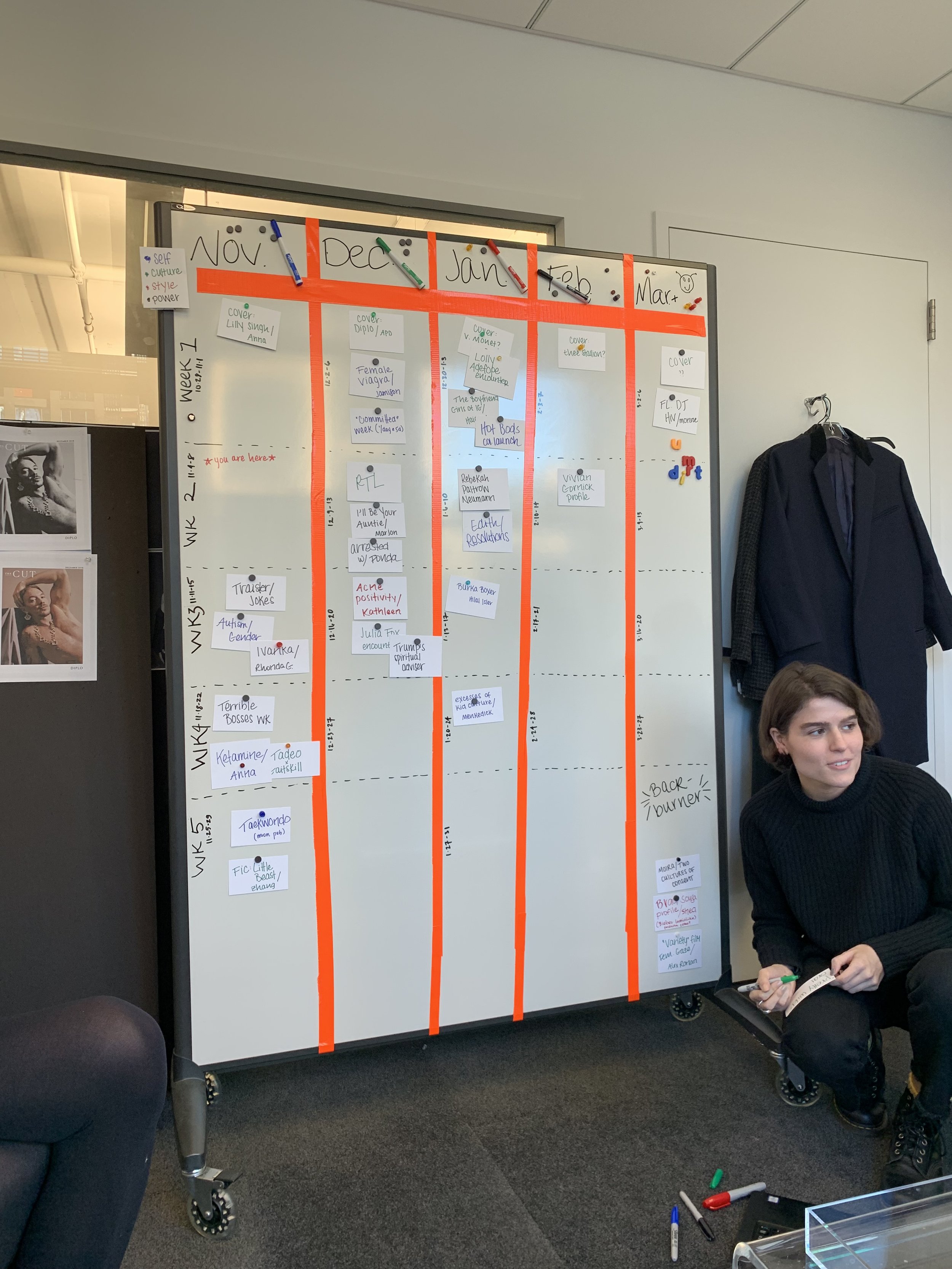

Patrick Mitchell: And one of the tools that I think gets forgotten that I think is specific to the magazine business is the ability to be nimble, to be able to pivot, to be able to respond and react. One of the things that I always felt alienated me from non magazine stuff was that whole presentation process where you come up with an idea and you go all in on that idea and if it doesn’t work, they completely start over. So you can’t slide like you can in a magazine. Deb, why don’t you take us back?

Debra Bishop: Sure. So Scott, let’s go back to the beginning. Can you share what it was like growing up in Lubbock, Texas?

Scott Dadich: Lubbock was tough on me. I have such affection for the people and the generosity of the place. The sort of spirit of being a Texan and growing up in what basically was a pretty small town. But I also felt really constrained by it. I felt bored a lot. I felt like I didn’t have a big community of people. My parents had moved to Lubbock and away from family. So the big, familial unit really wasn’t there. It was just me, my mom, dad, and sister. And just there together. So it felt like a lot to navigate at times.

Patrick Mitchell: Moved to Lubbock from where?

Scott Dadich: I was born in Tucson, Arizona. My dad was a tennis pro and he was working at the country club there. And my mom was a nursing professor. And my mom actually got the job. One of the first faculty at the Texas Tech School of Medicine and Nursing. And so that was 1980, I think, we moved there. But they were both East Coasters. My dad was actually from Chicago and my mom from Queens.

Debra Bishop: So were there inspirations or magazines that sort of helped your boredom in those days.

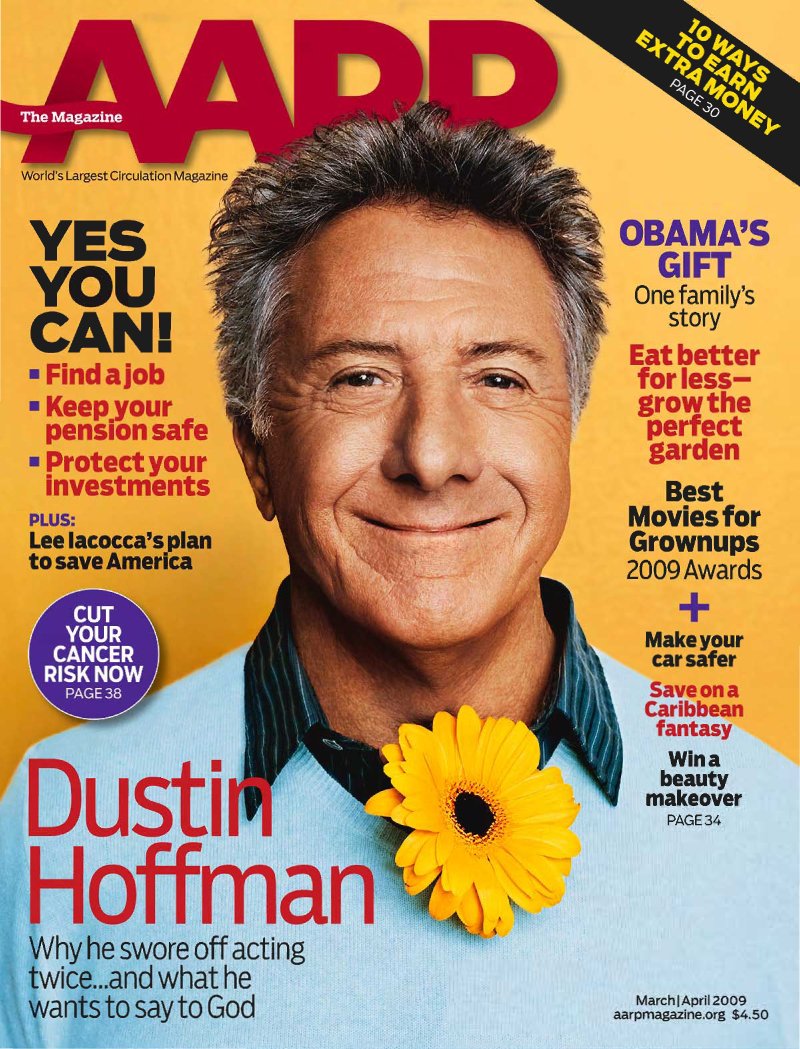

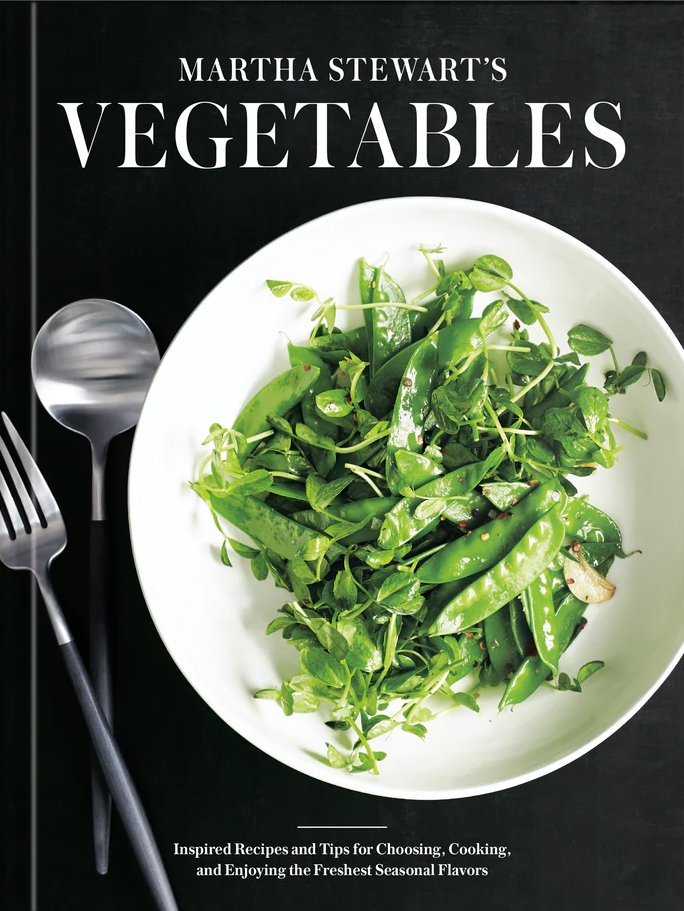

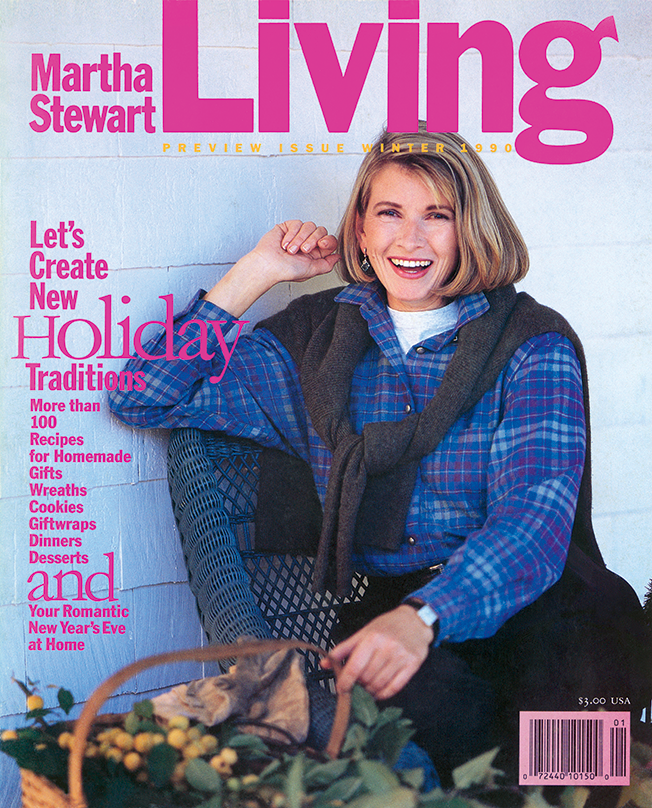

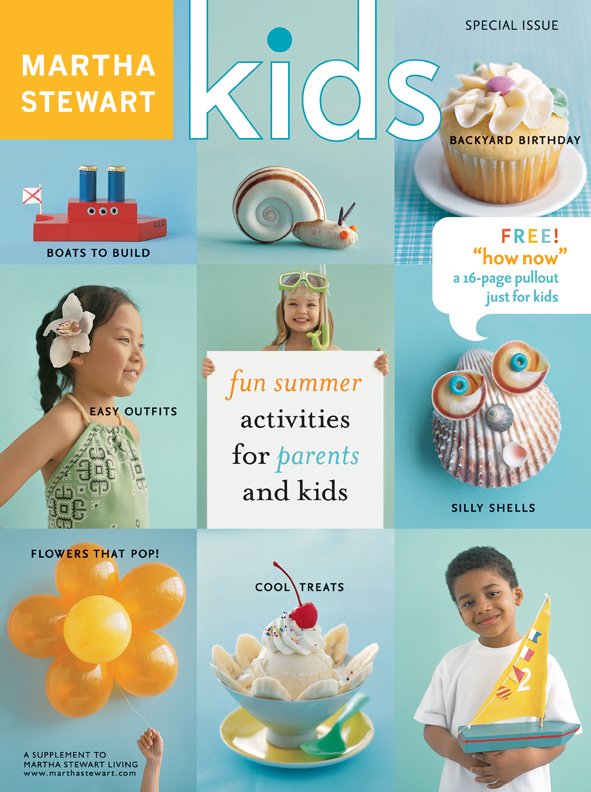

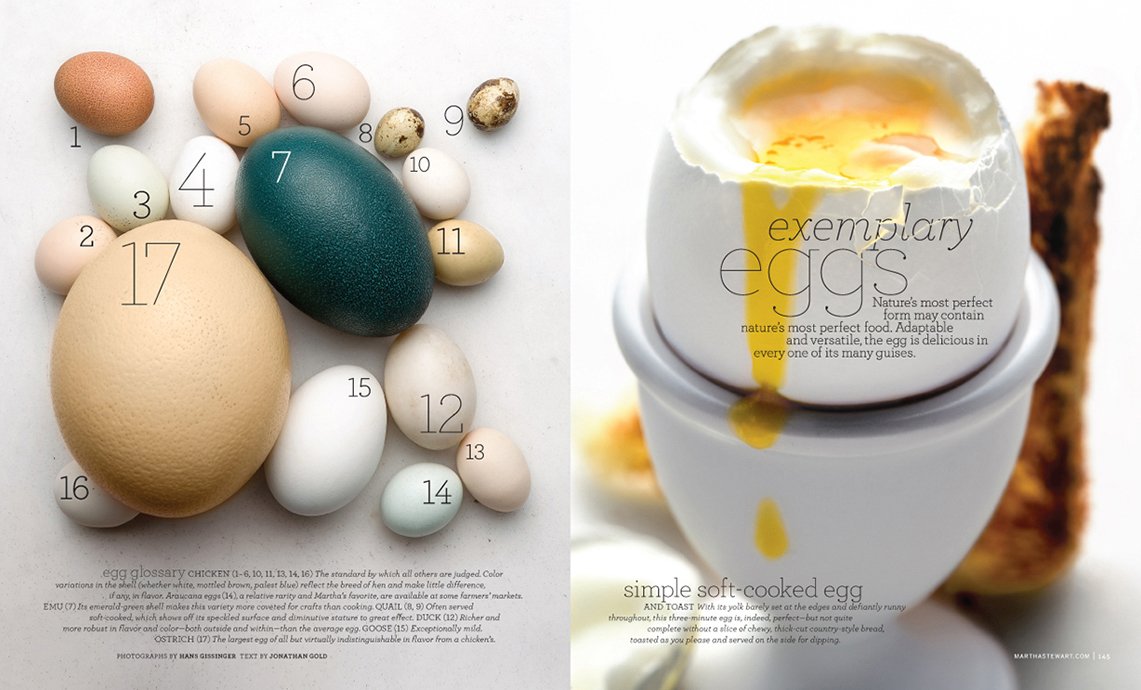

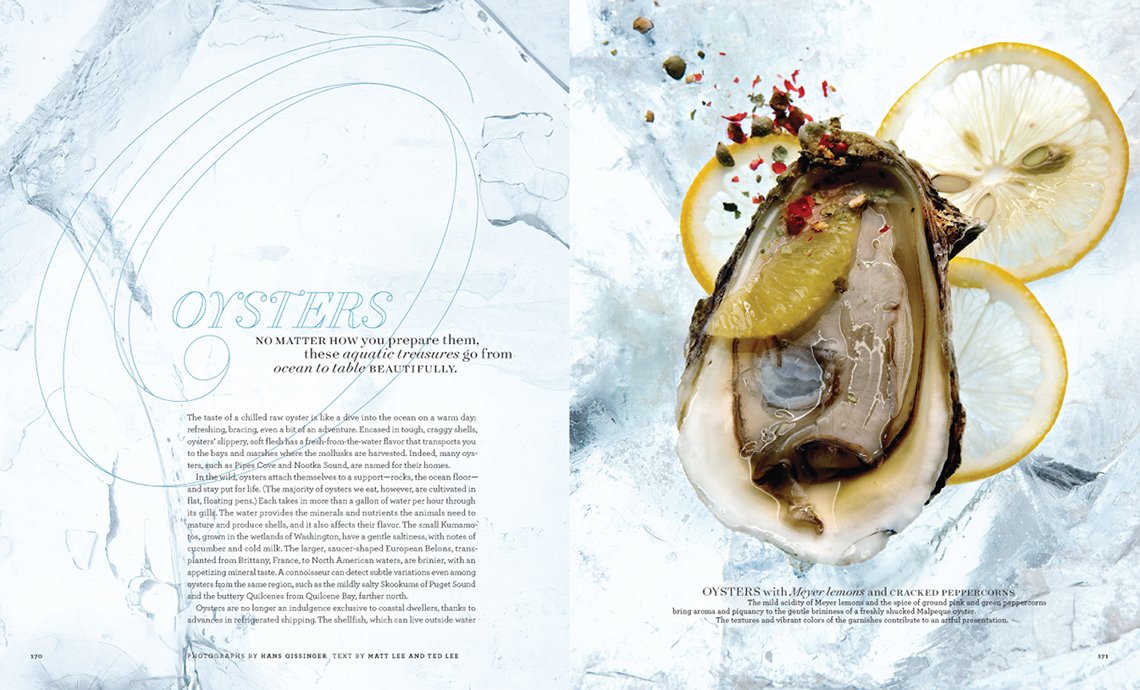

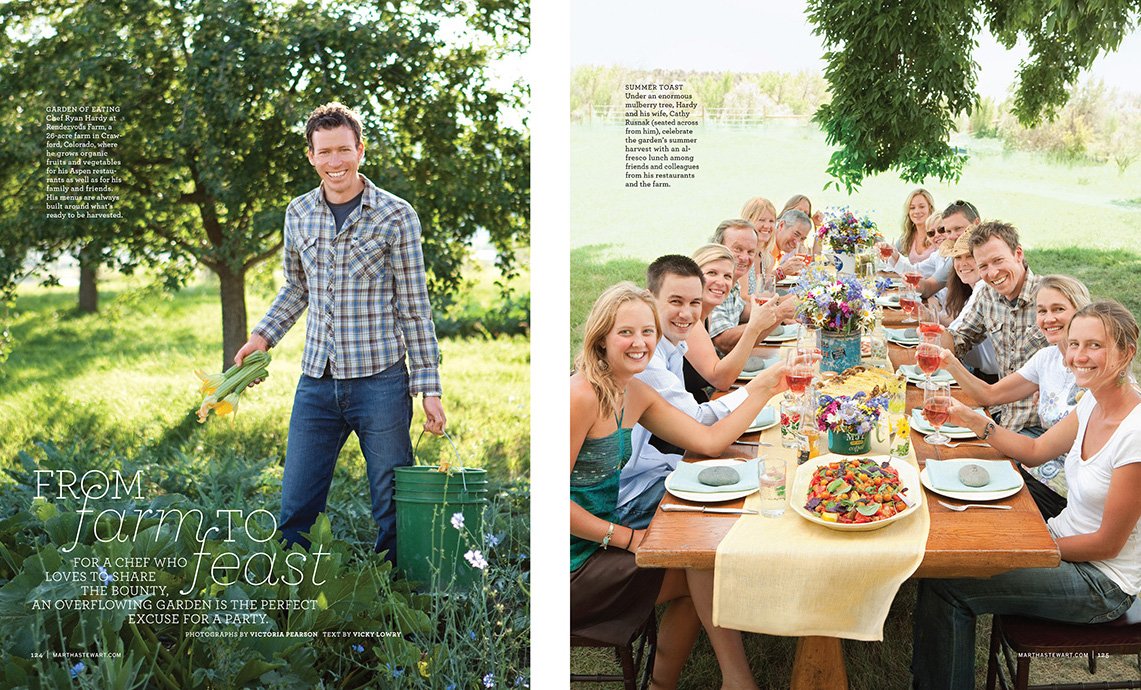

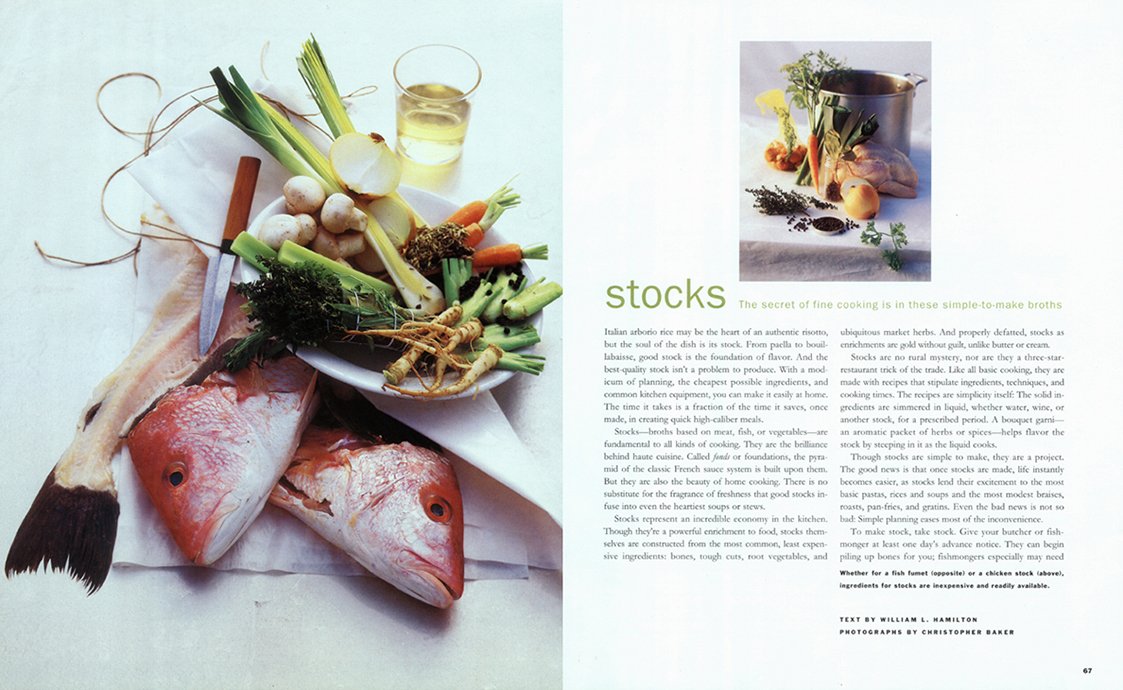

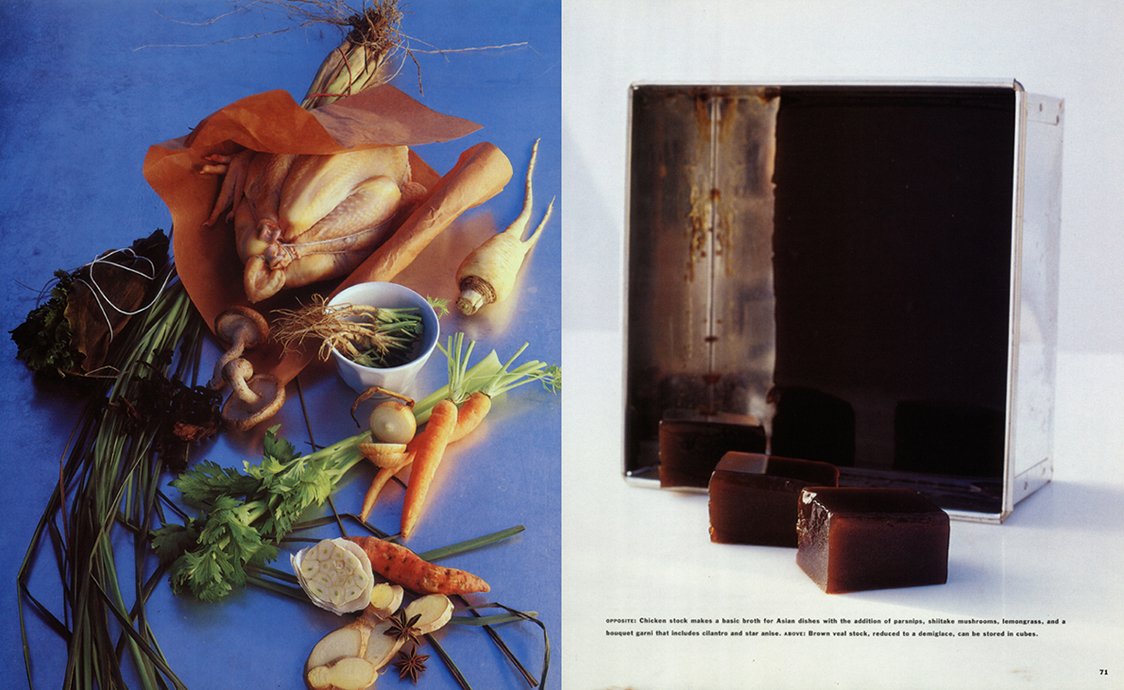

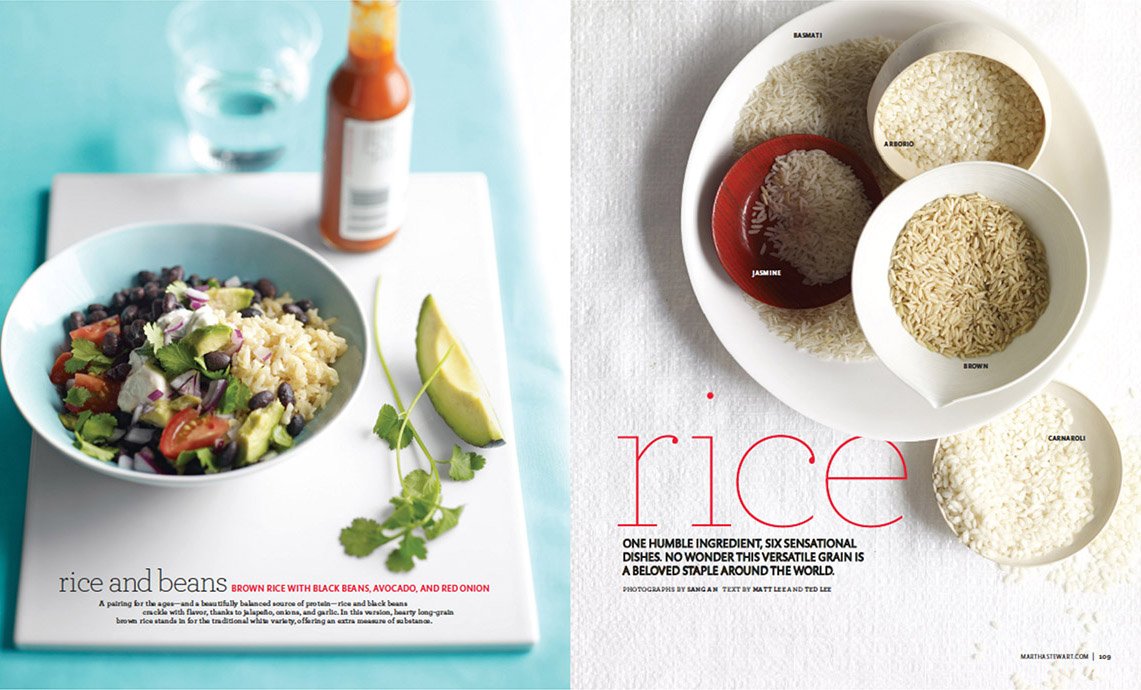

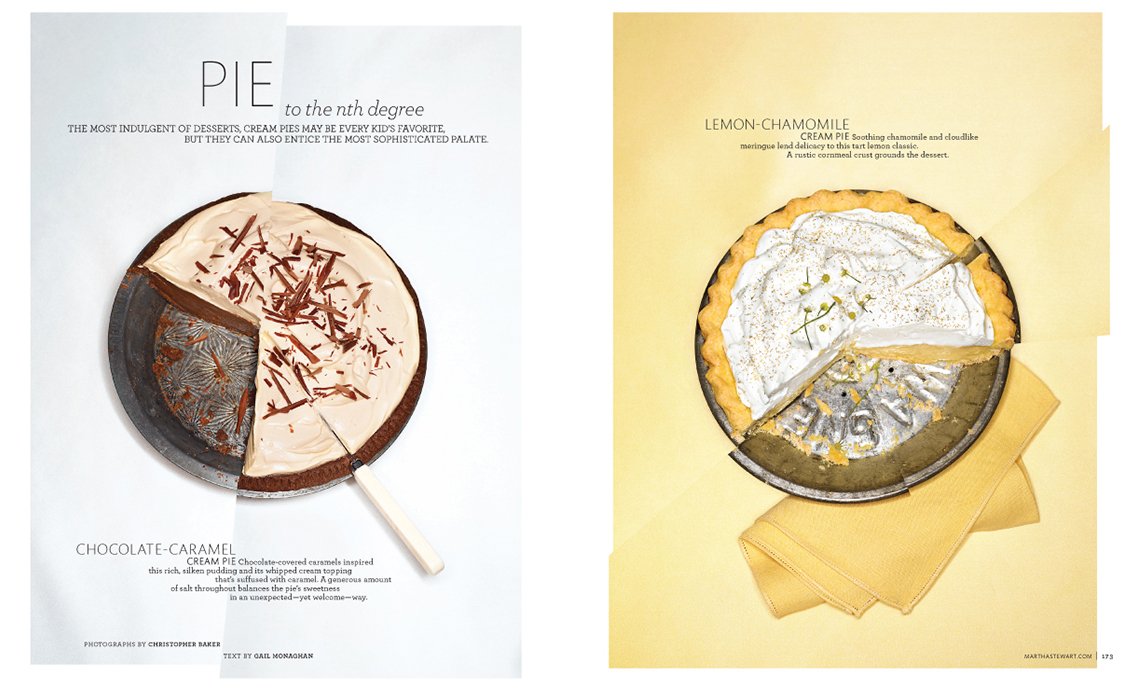

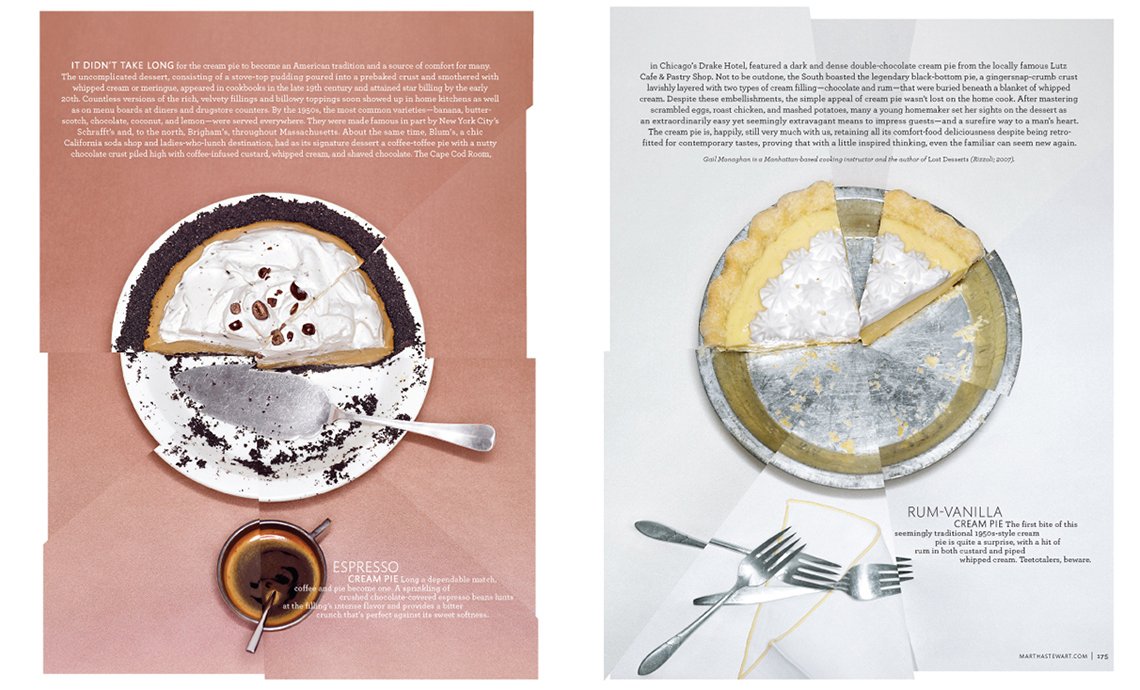

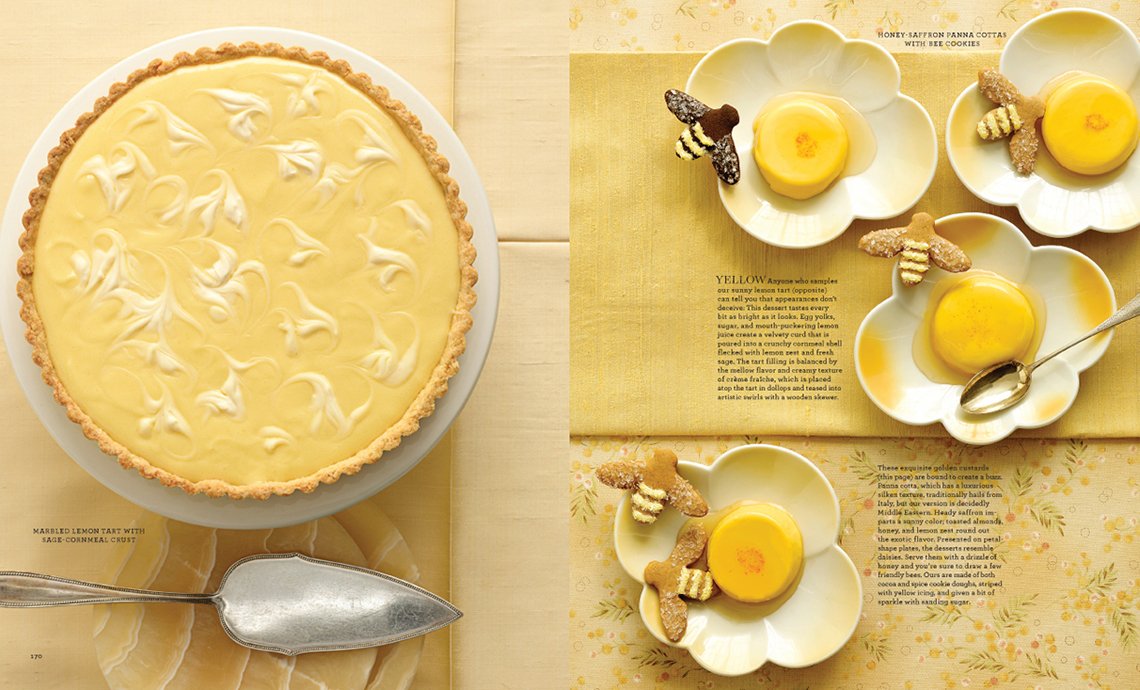

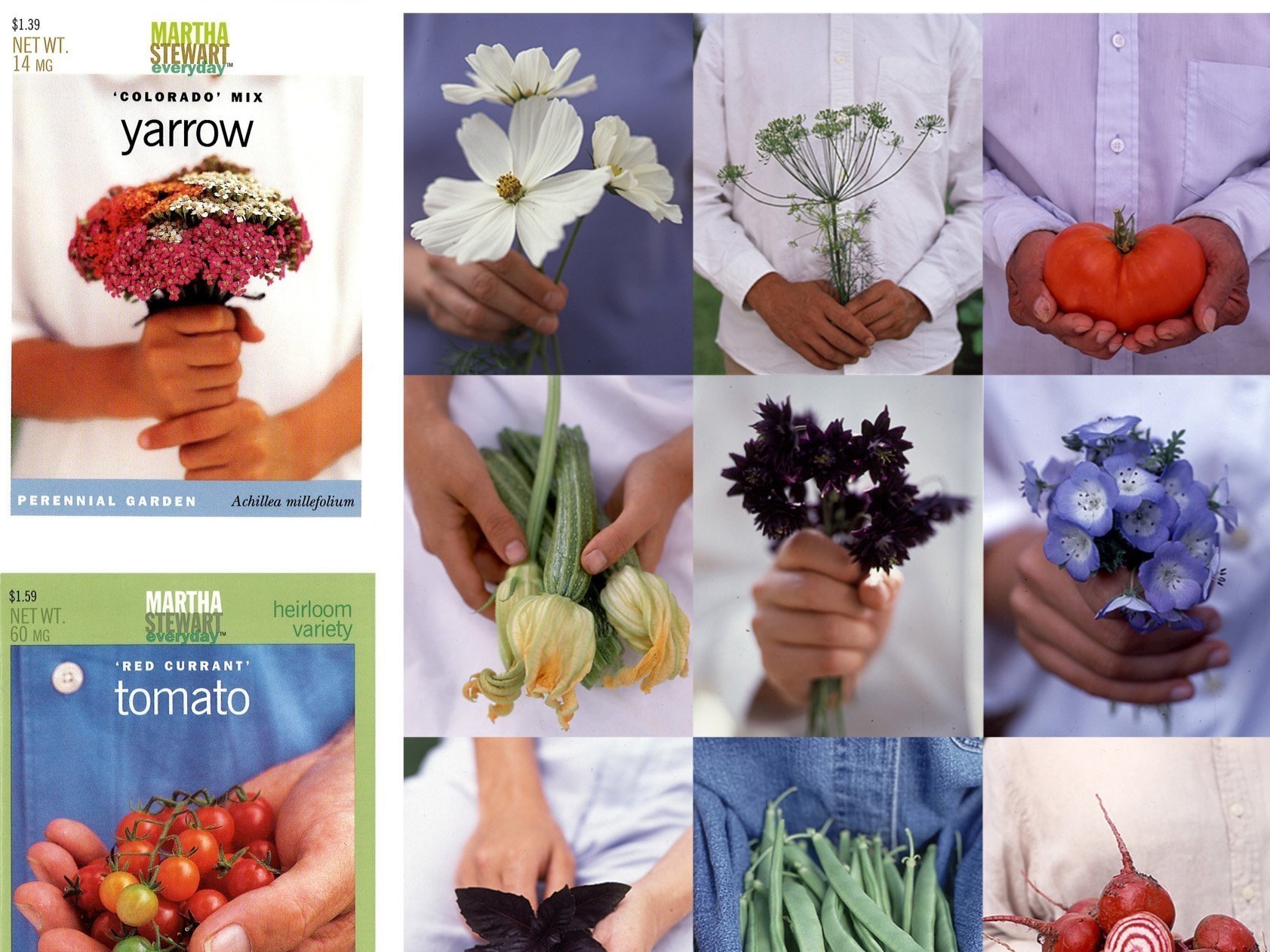

Scott Dadich: Funny enough, as a listener of the pod, I’ve noted the Ranger Rick continuity. Ranger Rick was definitely in there, definitely in the mix. But I remember definitively Martha Stewart Living as one of my mom’s favorite magazines and the stacks and stacks of them around the house, and originally thinking that was my mom’s magazine, but getting into it and discovering so much joy in those pages.

And then Texas Monthly was the other one. Texas Monthly was always the grocery store buy. The thing that we would see on the newsstand at the checkout aisle and you’d always pick up Texas Monthly and put that in the cart.

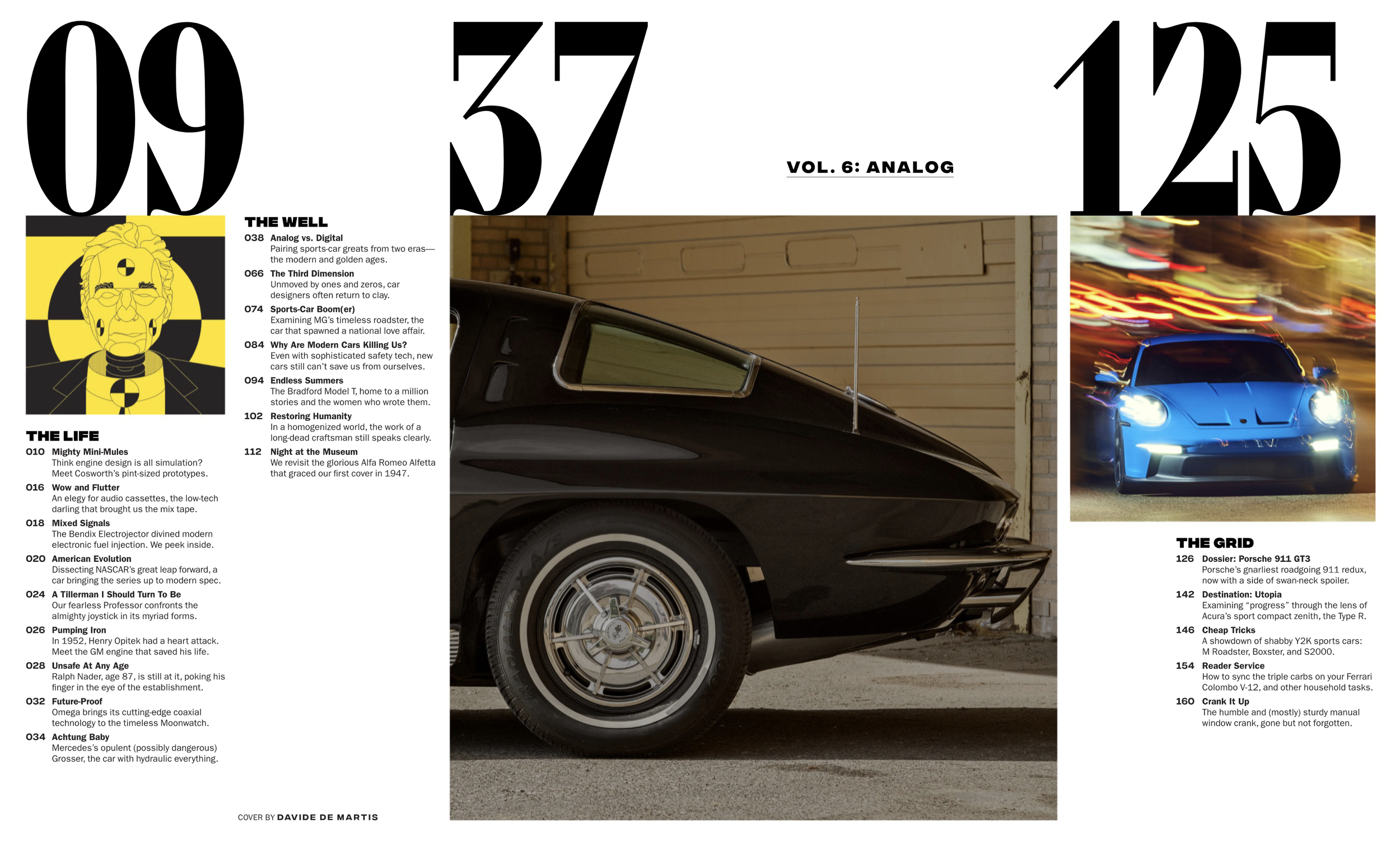

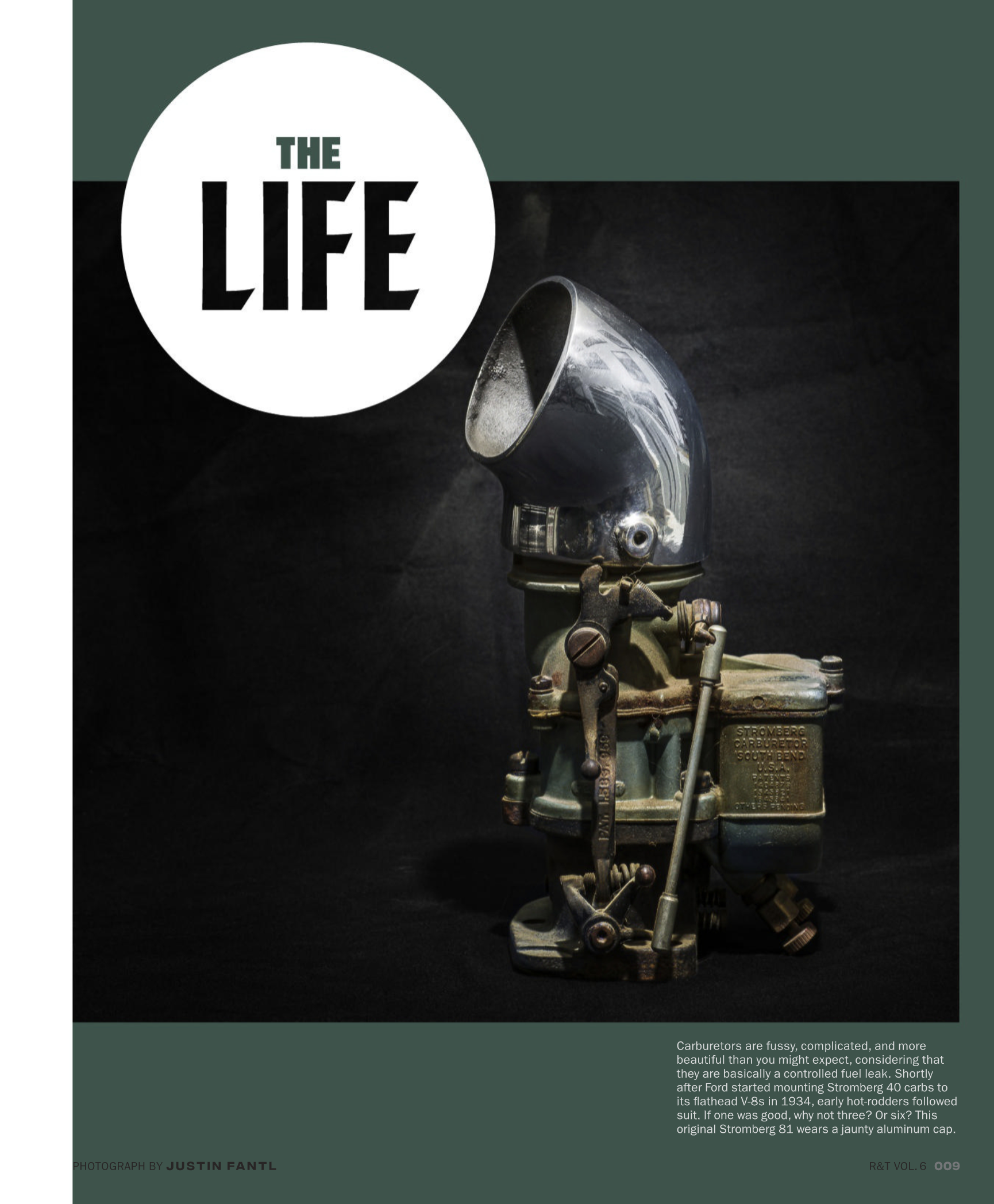

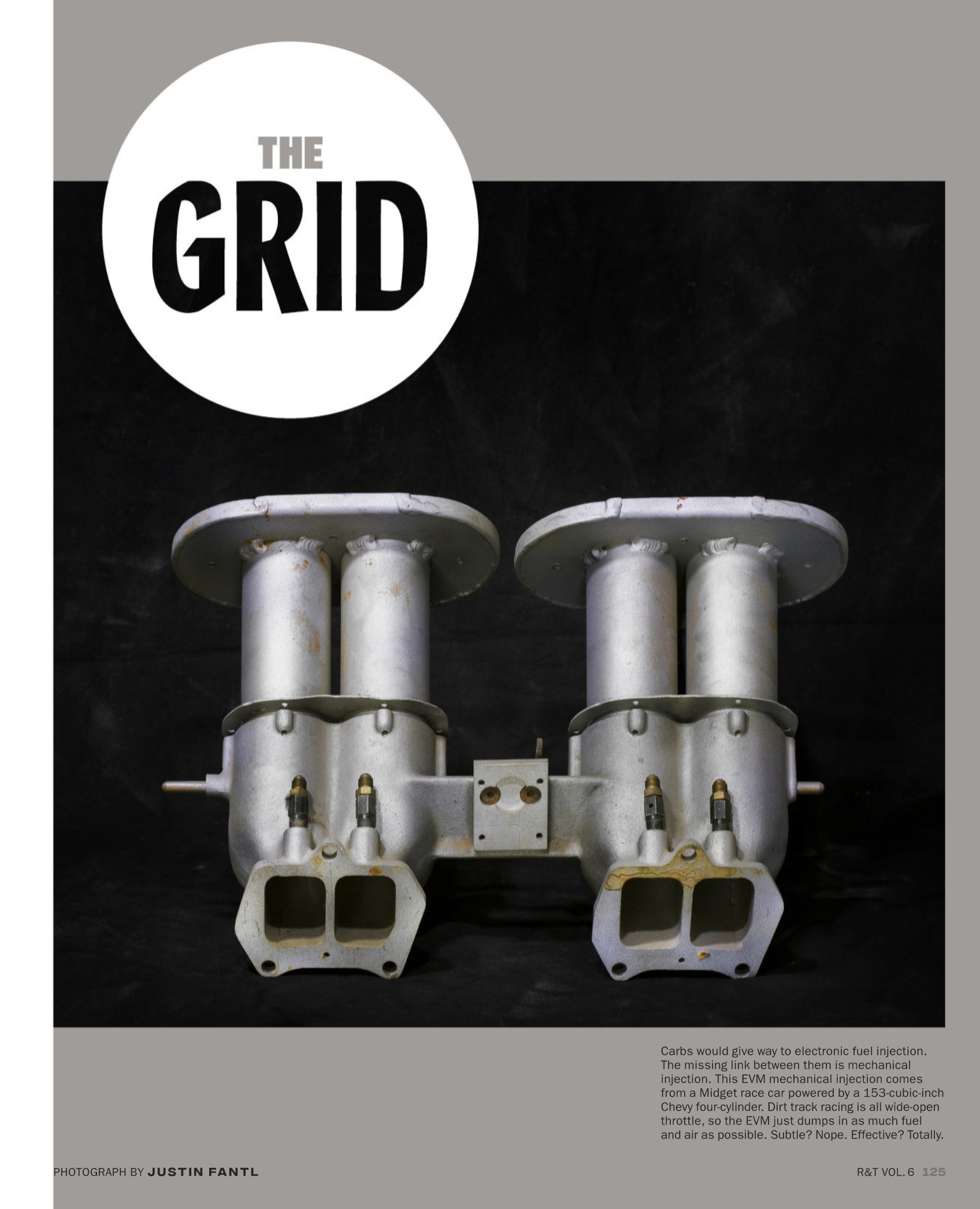

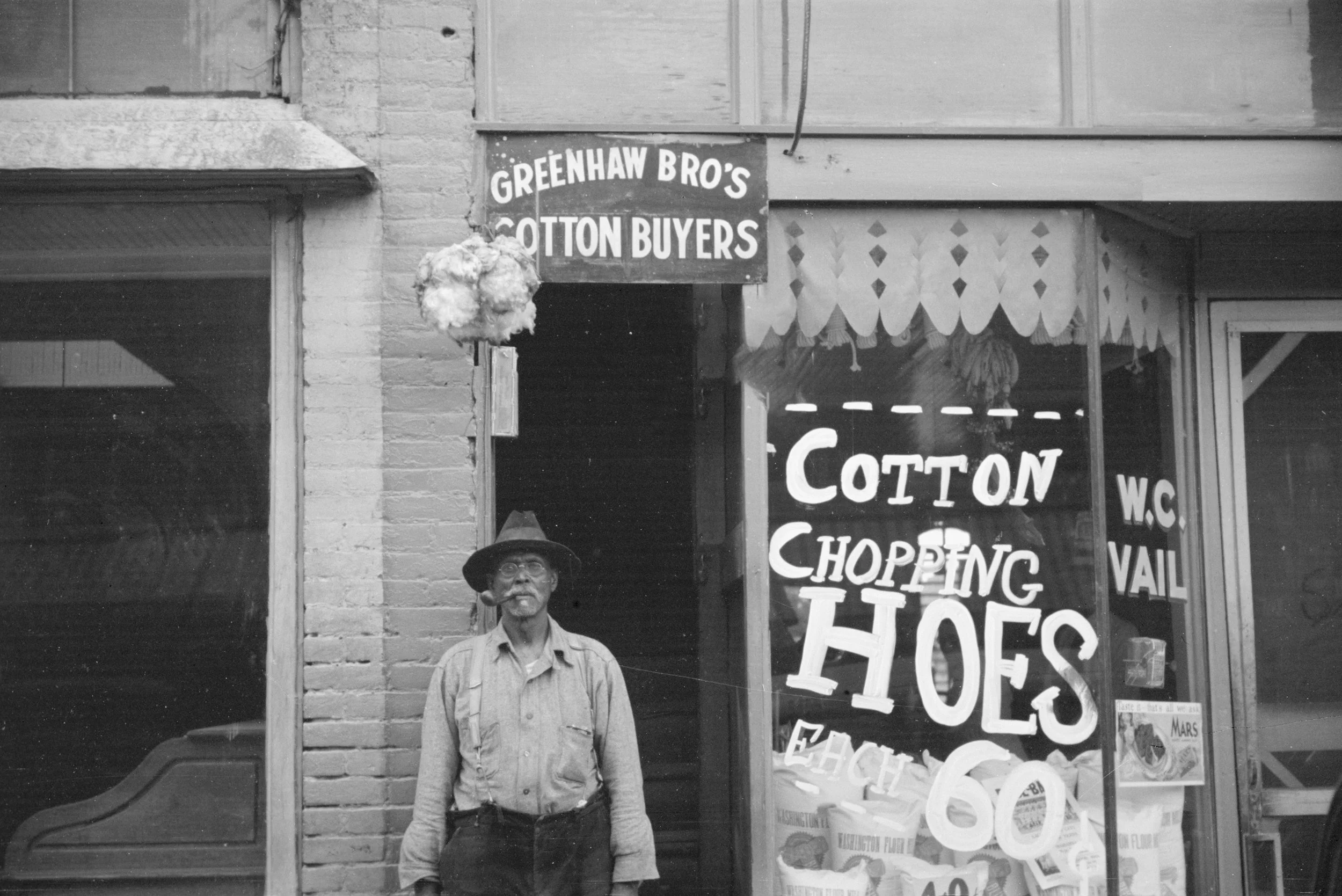

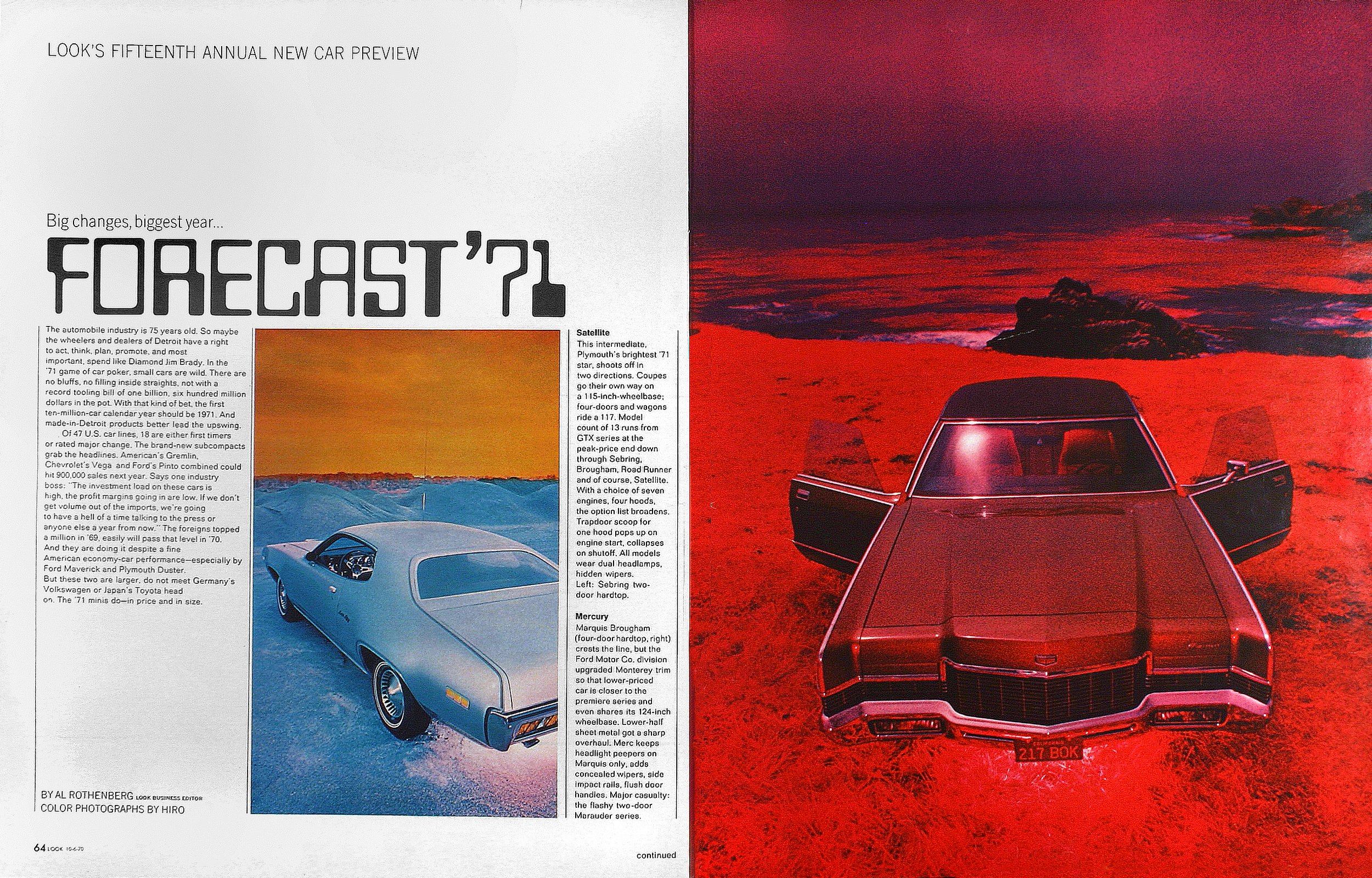

Those two were big lifelines. And that sort of led me into the rabbit hole. And I’ve always been interested in cars and racing. And so Motor Trend and Road & Track were soon to follow and getting those subscriptions and having things come to the house really became a lifeline. And feeling that there was a bigger world out there beyond the cotton fields of Lubbock.

Debra Bishop: Was there a Eureka! moment that led you to graphic design?

Scott Dadich: There wasn’t in school. The eureka! moment’s a weird story if you want to hear it. So I had this sort of magazine affection, but it didn’t ever click that there were human beings who got paid, that it was their career, to make these things. That never occurred to me.

I really did chase the car thing. And I was really good at math and science in school. And I remember my high school guidance counselor pushing me—and my parents—pushing me into following engineering as a path.

And I used to build model cars. My whole bedroom was just a model-making factory. And I wanted to design cars. But I didn’t connect the thought of the intentionality of a design process and an automobile. And I just got pushed into mechanical engineering and actually got a scholarship to go to the University of Texas to chase that—longer story—but was anorexic, and sick, and misguided, and on the wrong track.

And so I moved back to Lubbock, and enrolled in Texas Tech, and moved in with my best buddy from high school. And he was working at a bagel shop, the first bagel shop in all of Lubbock. And it had just opened up and it was a mom-and-pop—Phil and Marian Hoot. And I was a bagel baker, so I would go in every morning at three in the morning and make the bagels and get everything ready for the day.

And then I could go to school, and I was just in general studies at Texas Tech at this point, in the afternoon. And one day, the owner, Marian, said, “When you open up, there’s going to be a sign painter in here and they’re going to be redoing the menu boards.”

And I was broke. And I’m like, “Whatever you’re paying the sign painter, I’m good at lettering. And I will do it for half of whatever they were going to charge you.” And they were just getting on their feet as a shop. So Marian took me up on it. “Okay, I’ll cancel it and let’s give it a go.” And it was those big black chalkboards and the fluorescent markers. And I had pastels and chalks and I just went nuts.

And I spent all night re-lettering and re-doing all the menu boards. And the next morning, one of our regular customers came in, this woman named Sonia Aguirre, she said, “I love the new menu boards. Those are great. And who did them?” And Marion points to me in the back and I’m making bagels. And I’m probably 19. And Sonia comes back and she said, “I’m an art director at an ad agency here in town. You’ve got real talent. And here’s my card. You should call me and do an internship with me at the agency.”

And I didn’t know what an art director was. I had no idea that it was a job. And one of my buddies who I worked with at the bagel shop was actually in design school. And I was comparing notes with him and told him about the interaction. He said, “Dude, you should totally take that. Design is awesome. I’m designing cereal boxes in my classes.”

“Oh, I love cereal. That’s amazing. I could do that.” So I went and saw Marion and that was the big eureka moment. The light bulb had gone off that there was not only a path here, but I could make a career out of this.

Debra Bishop: You’re still on the Texas Tech website. And the quote on the site—they quote you, probably for enrollment, “The professors gave the extra time and effort to see that my energies were pointed in a positive direction.”

Scott Dadich: Yes.

Debra Bishop: That’s your quote. What does that mean?

Scott Dadich: That is absolutely true. I have a tendency, I think, I’ve always had an affection for technology, and for invention, and progress. So I very quickly glommed on to the Mac as the vector for my interests in design. That the Mac would be the thing that would carry me through rather than the craft of design and the sort of thoughtfulness that I know my professors were trying to guide me into.

And I got enraptured early with Photoshop—and cars—scanning images out of Motor Trend and Road & Track and making these ridiculously terrible car collages. And, you know, took the tough love, and I was like, “I can make a whole career out of this. I’m going to be a Photoshop guy—a Photoshop jockey.”

I had amazing professors that really instilled the rigor that that was not going to be a path. And actually the care and attention to detail and study was going to be required for me to be successful in that space.

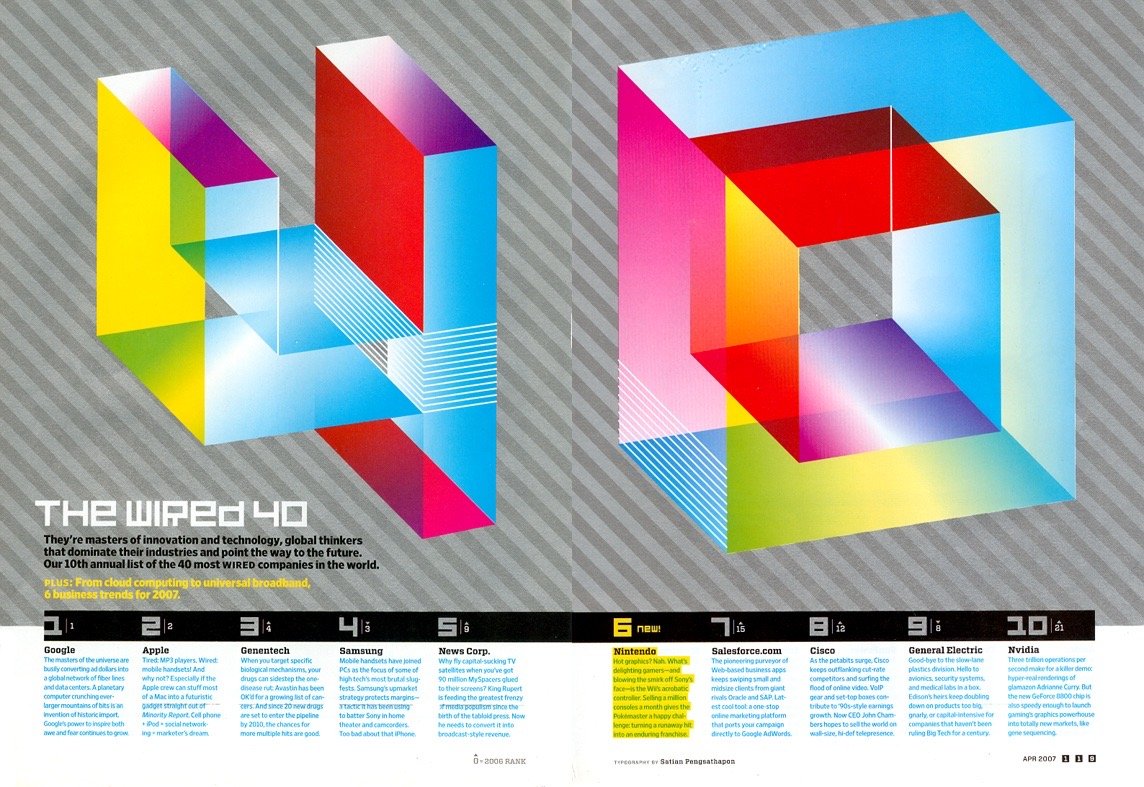

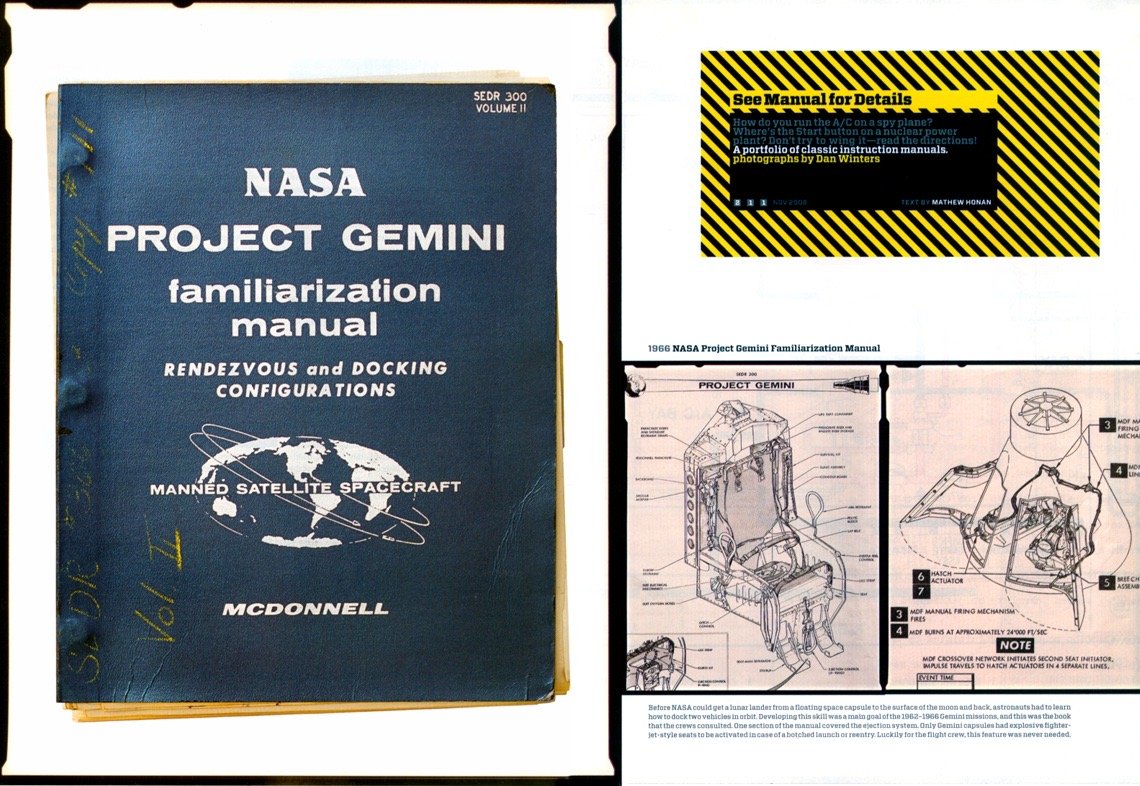

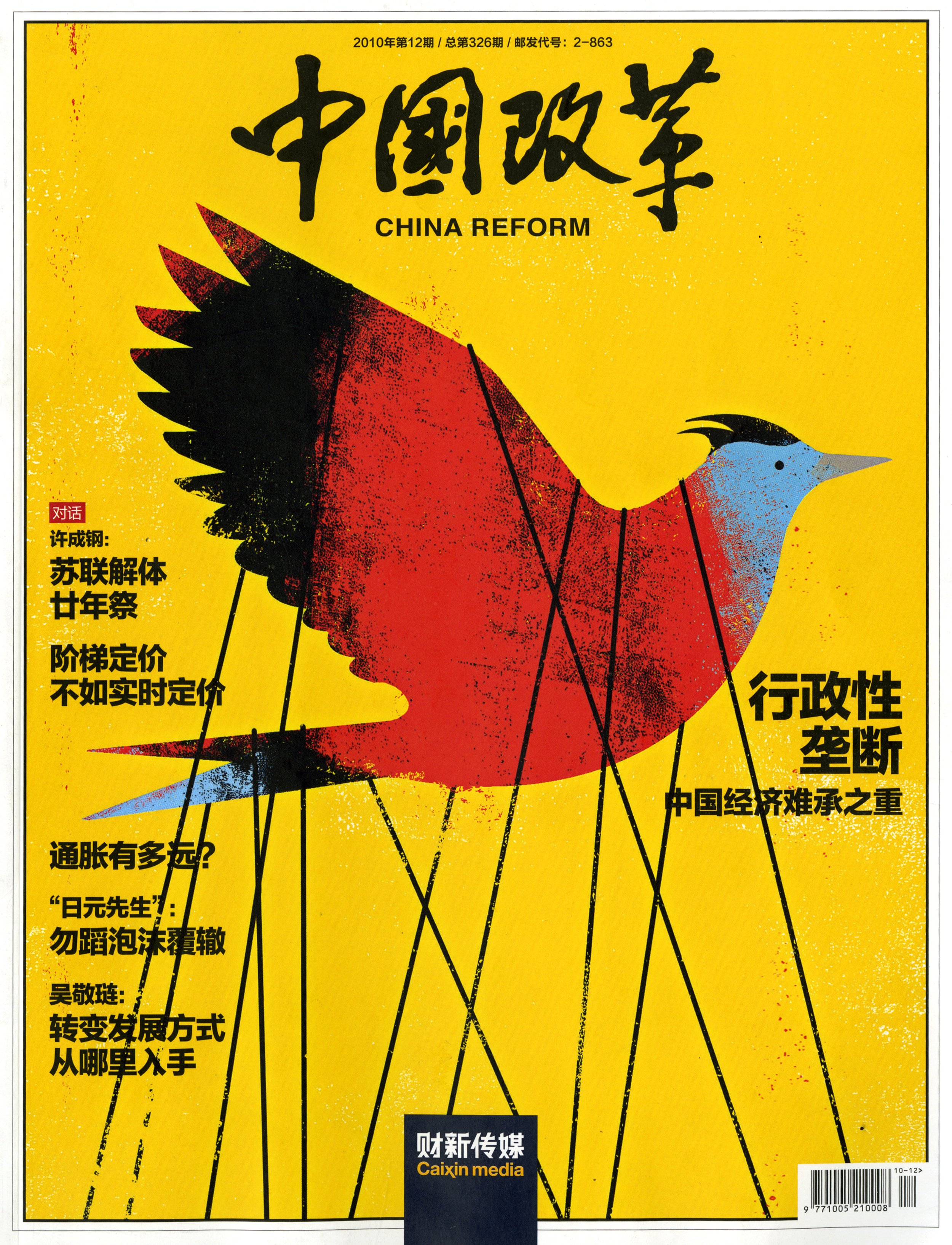

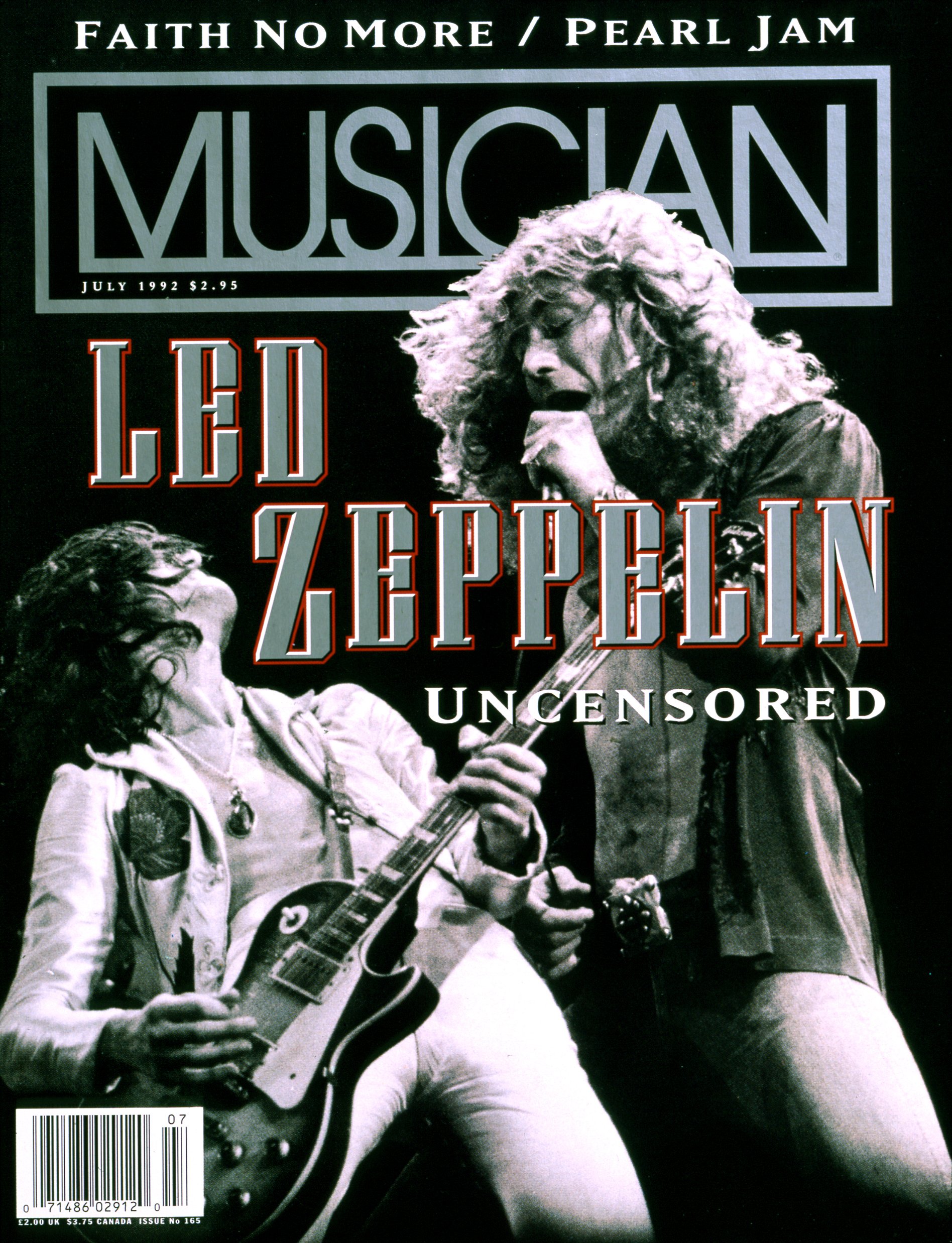

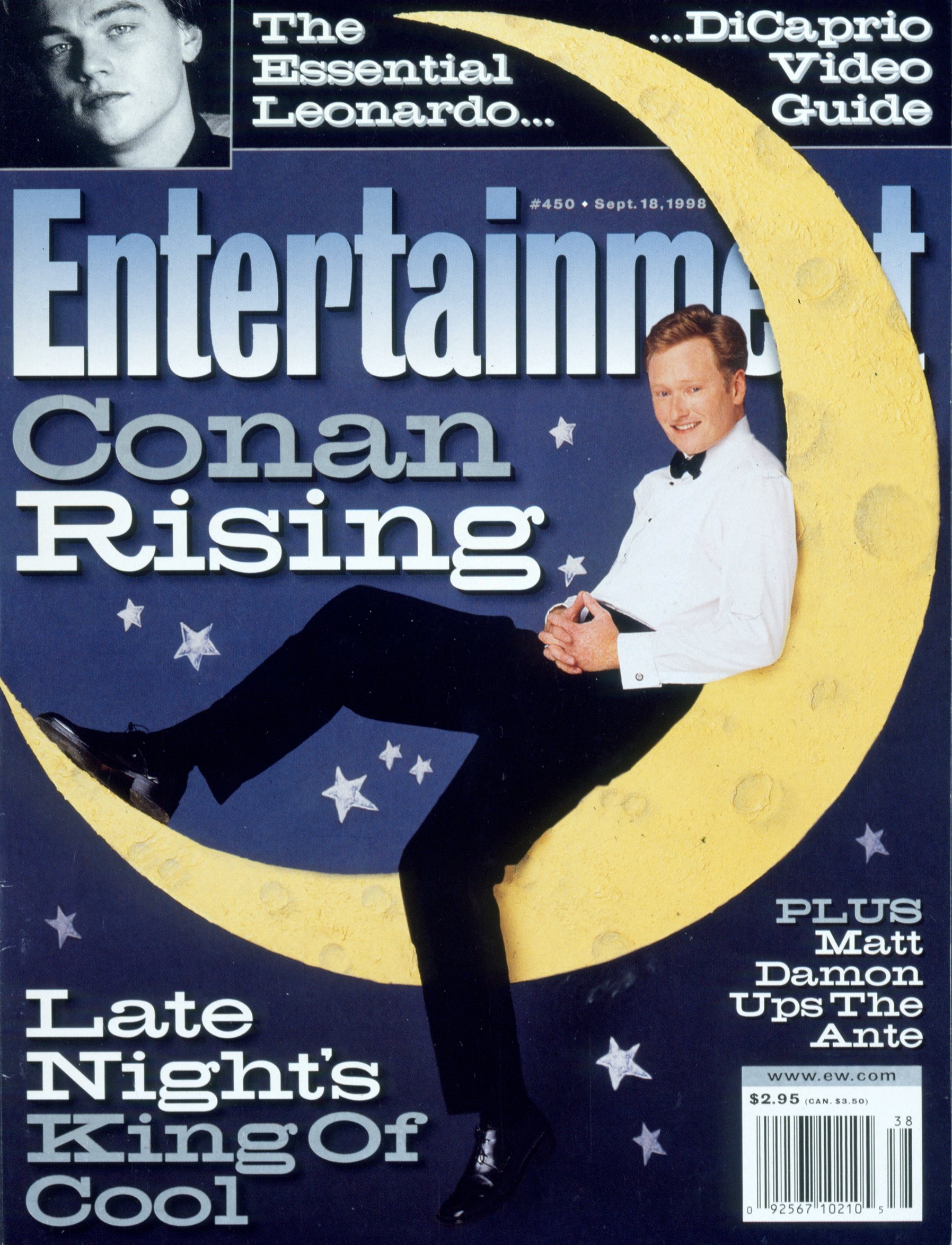

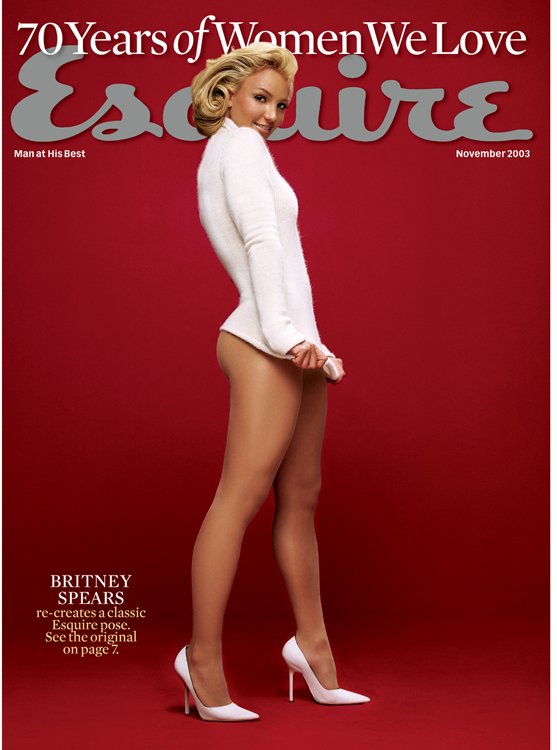

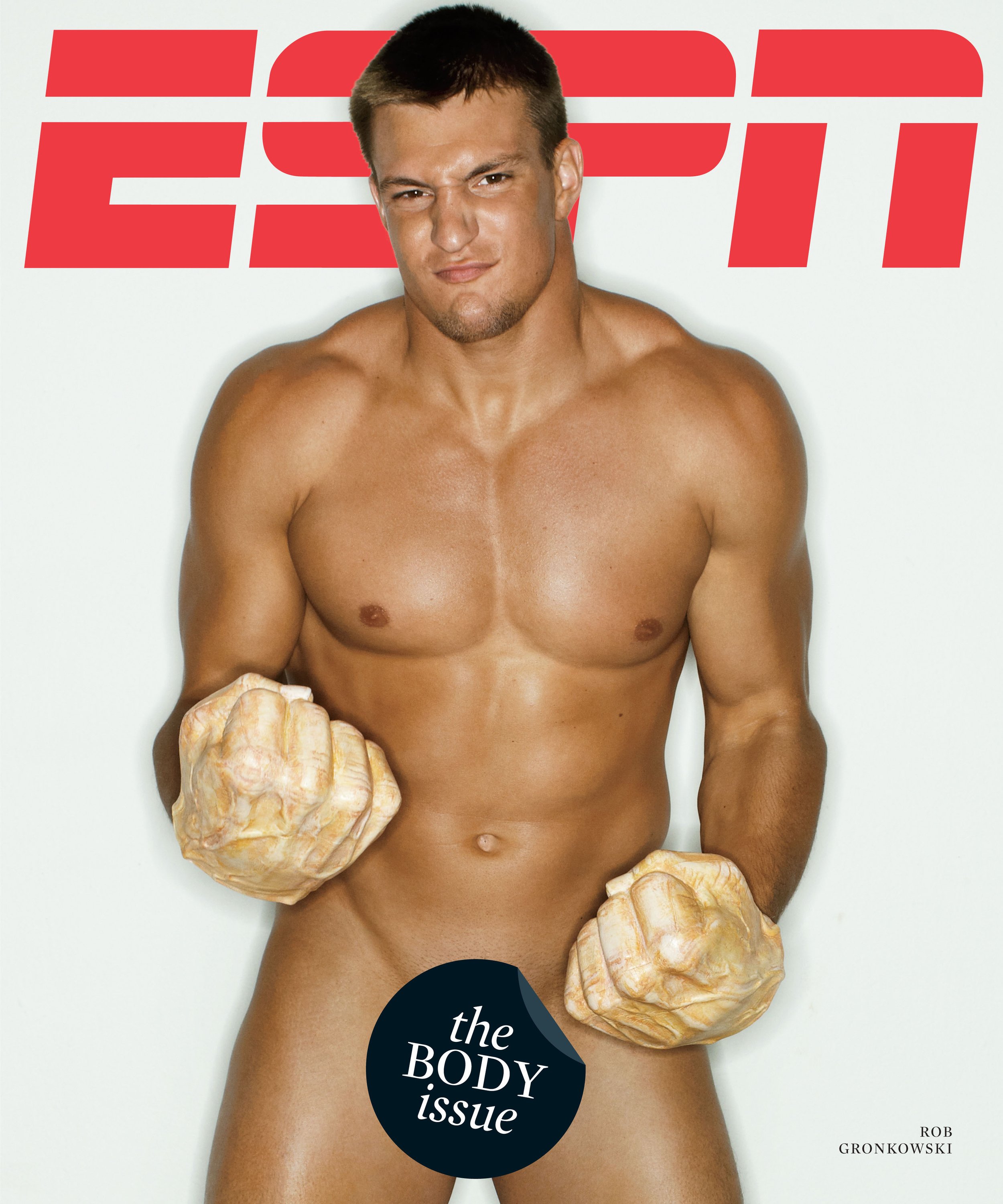

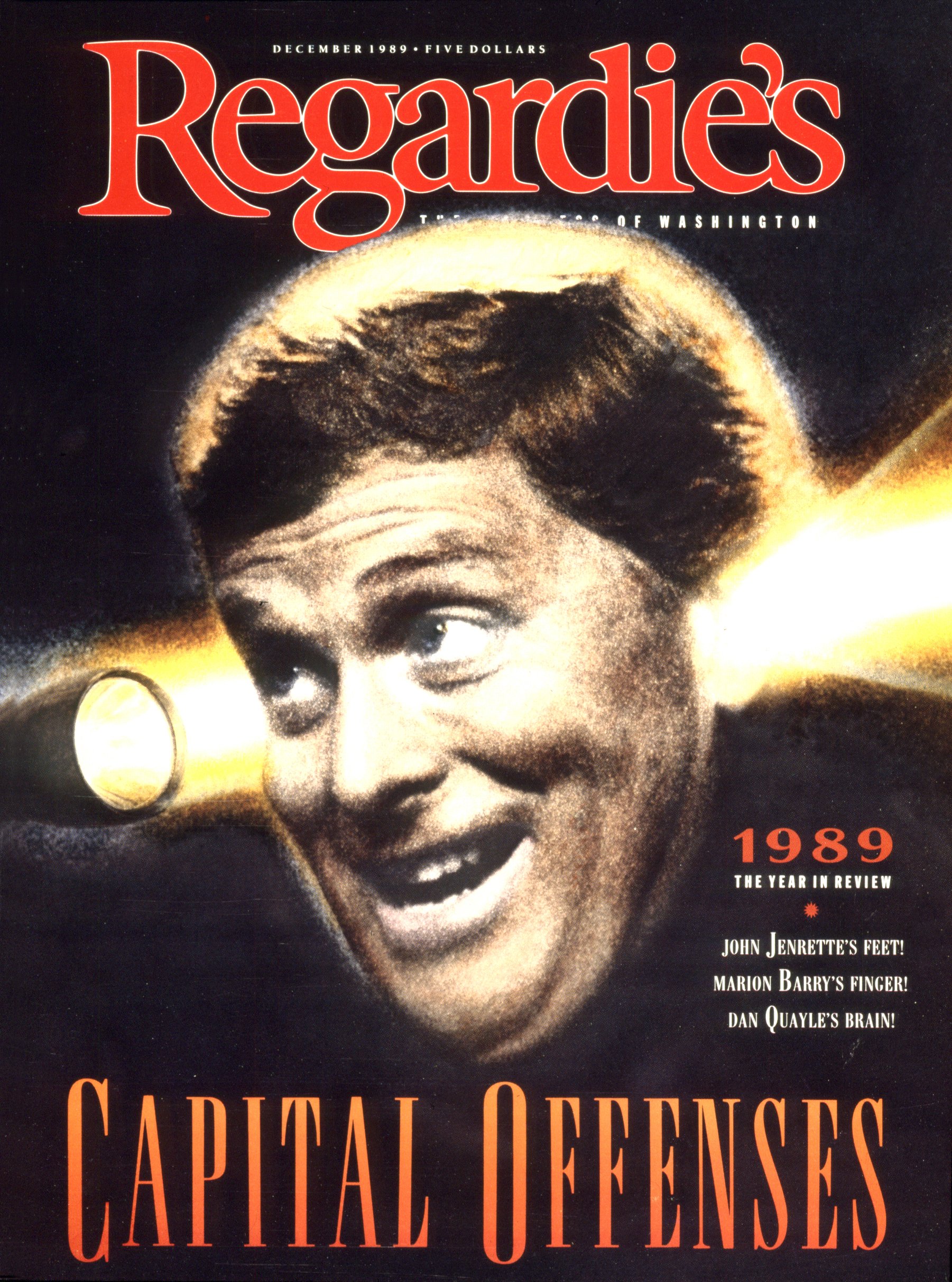

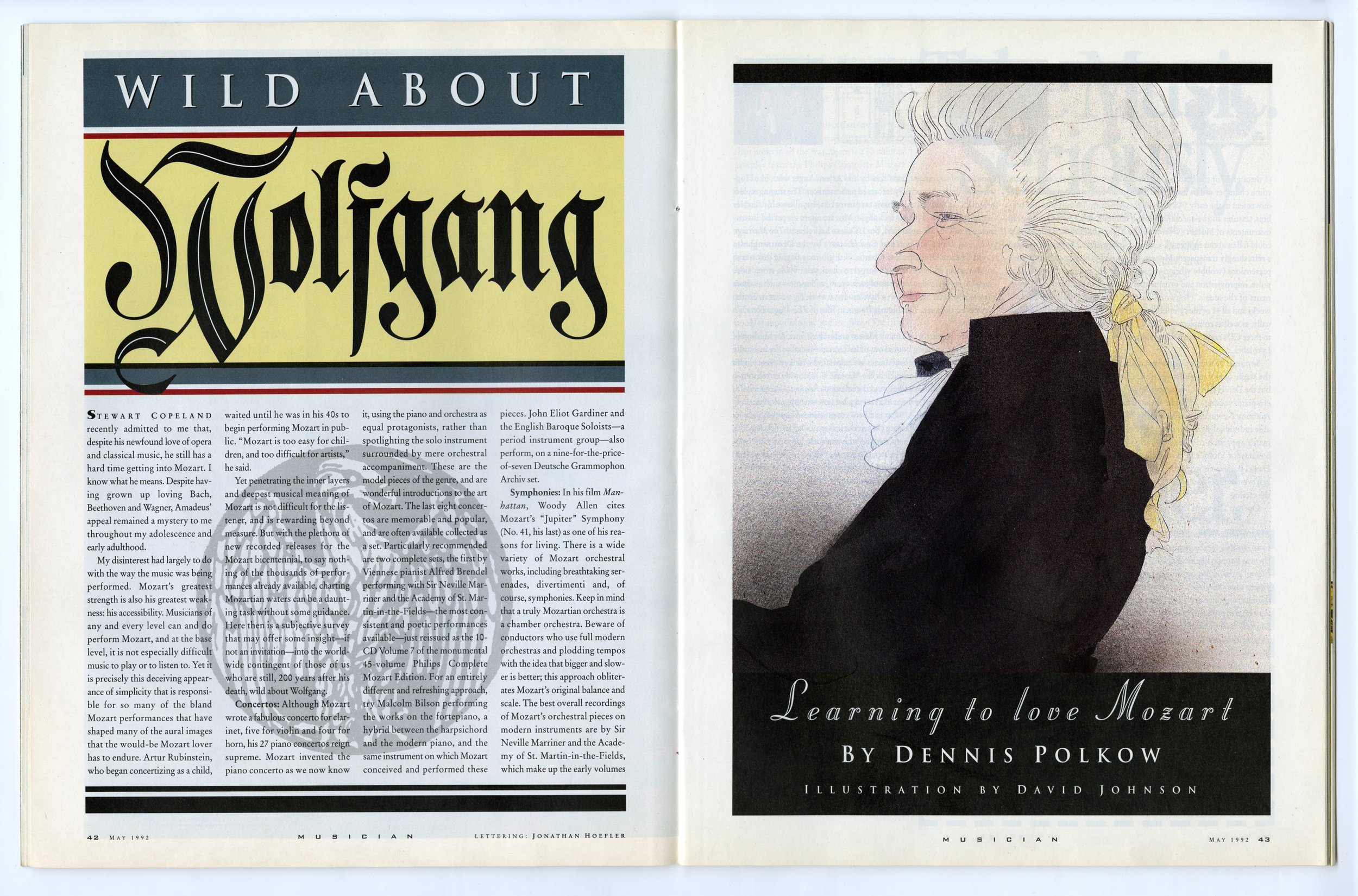

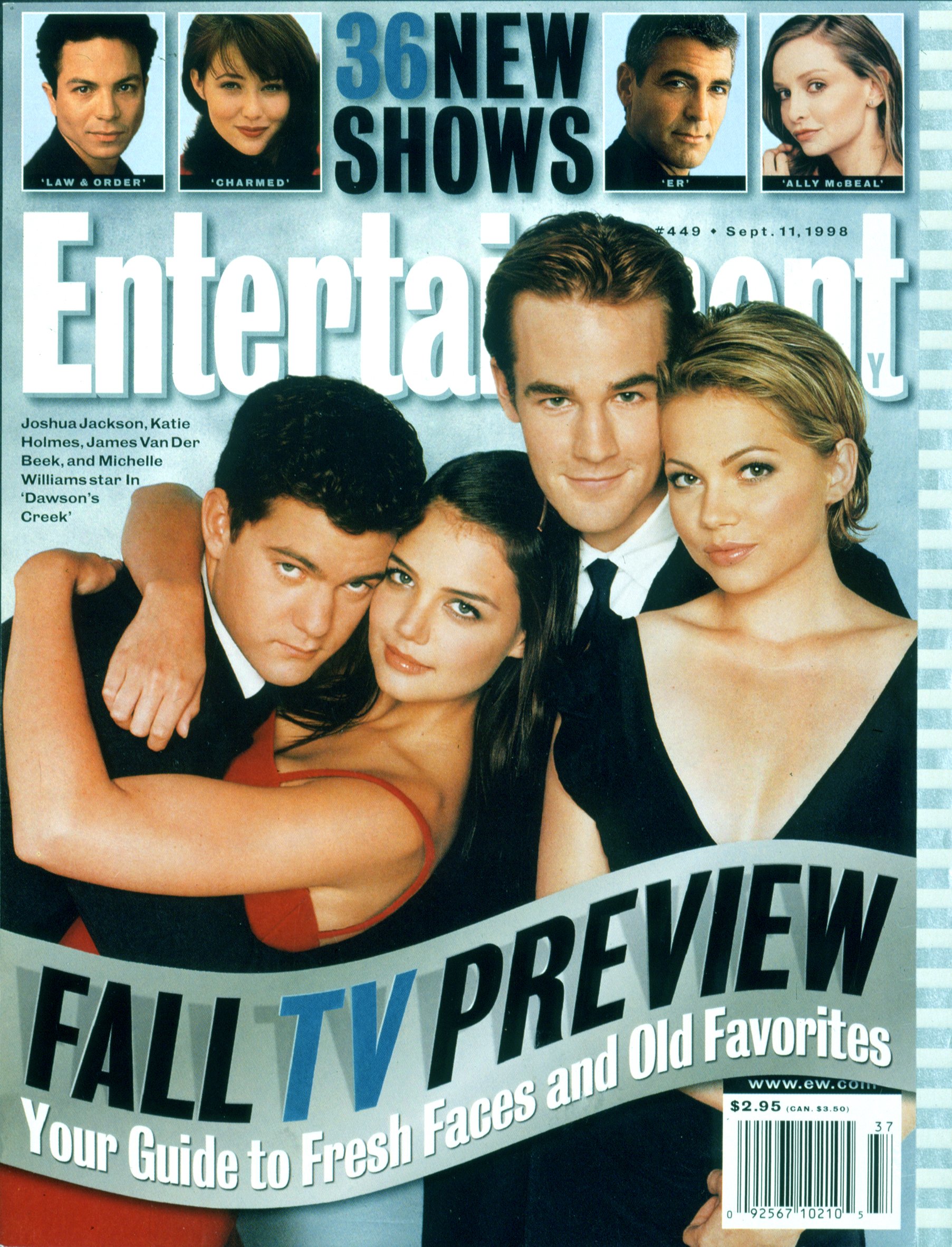

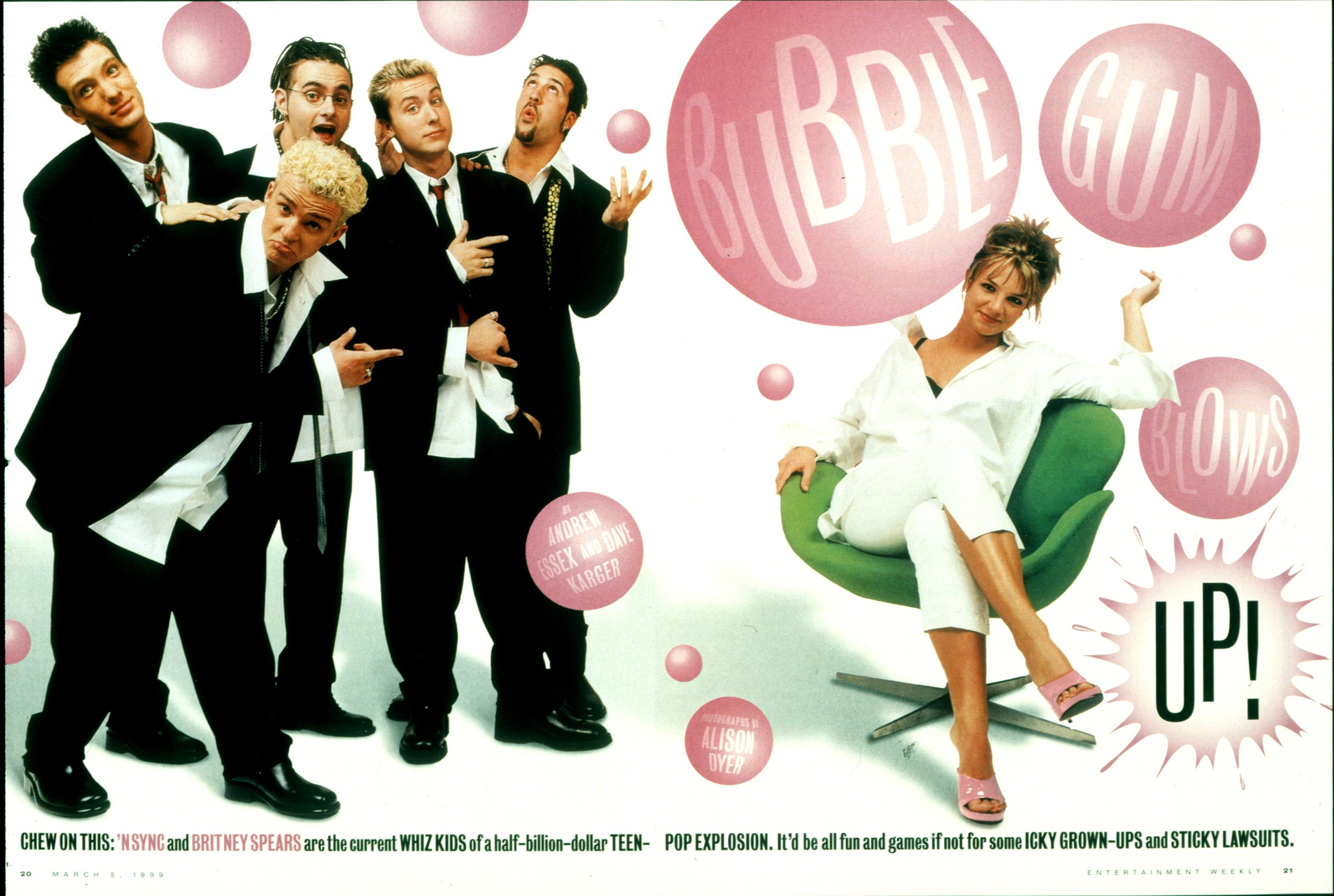

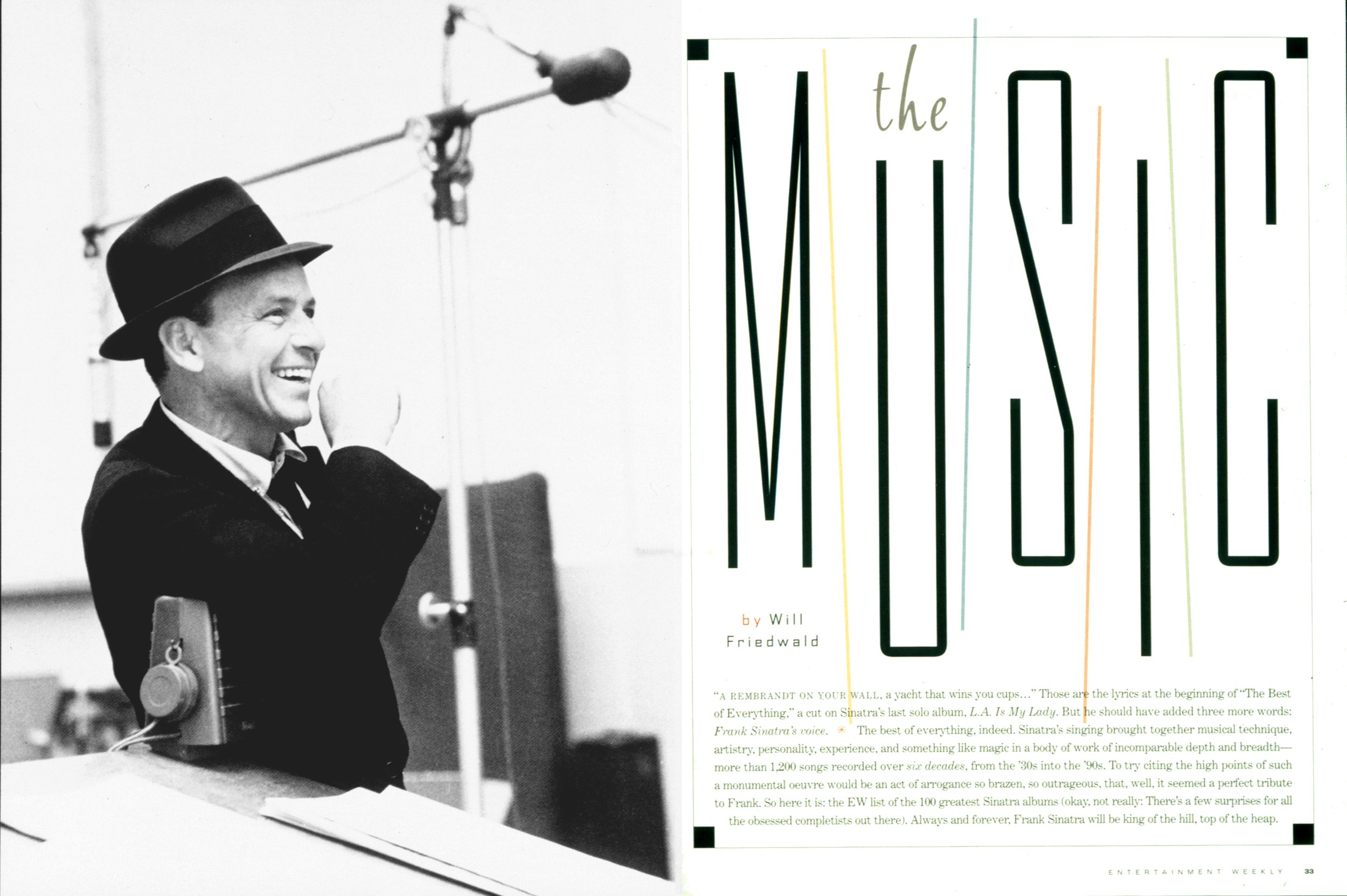

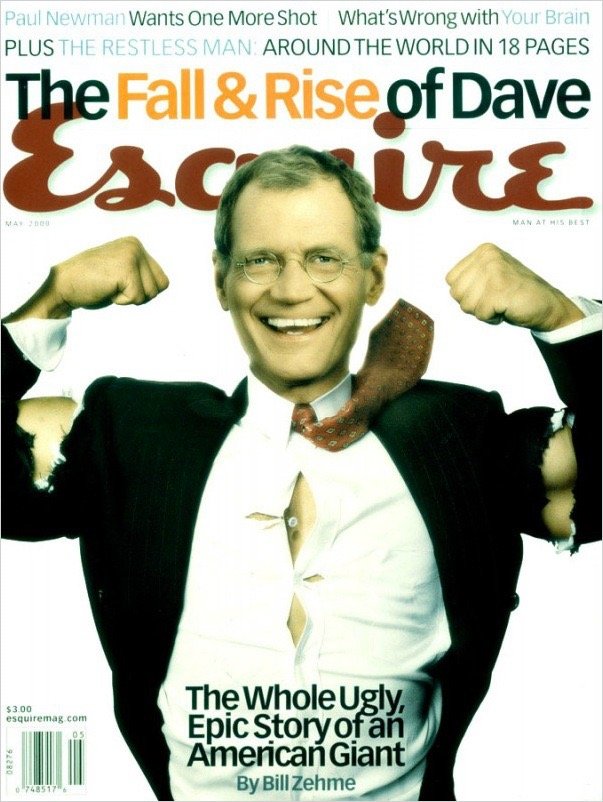

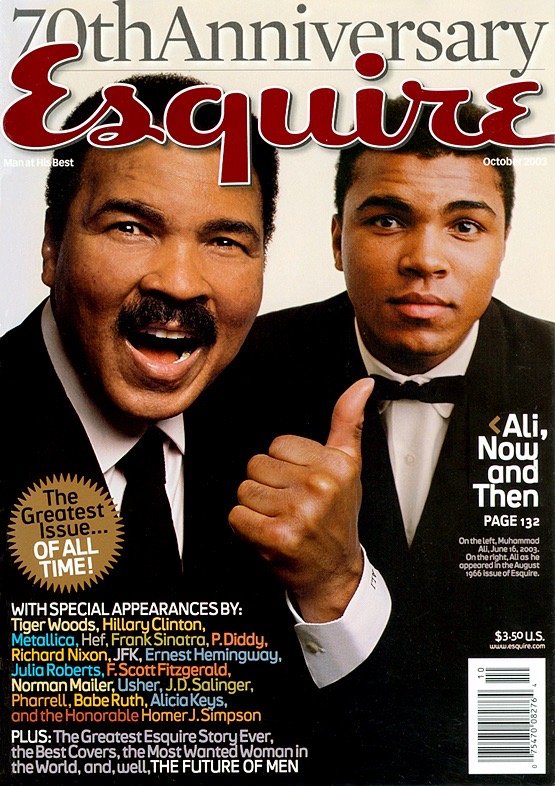

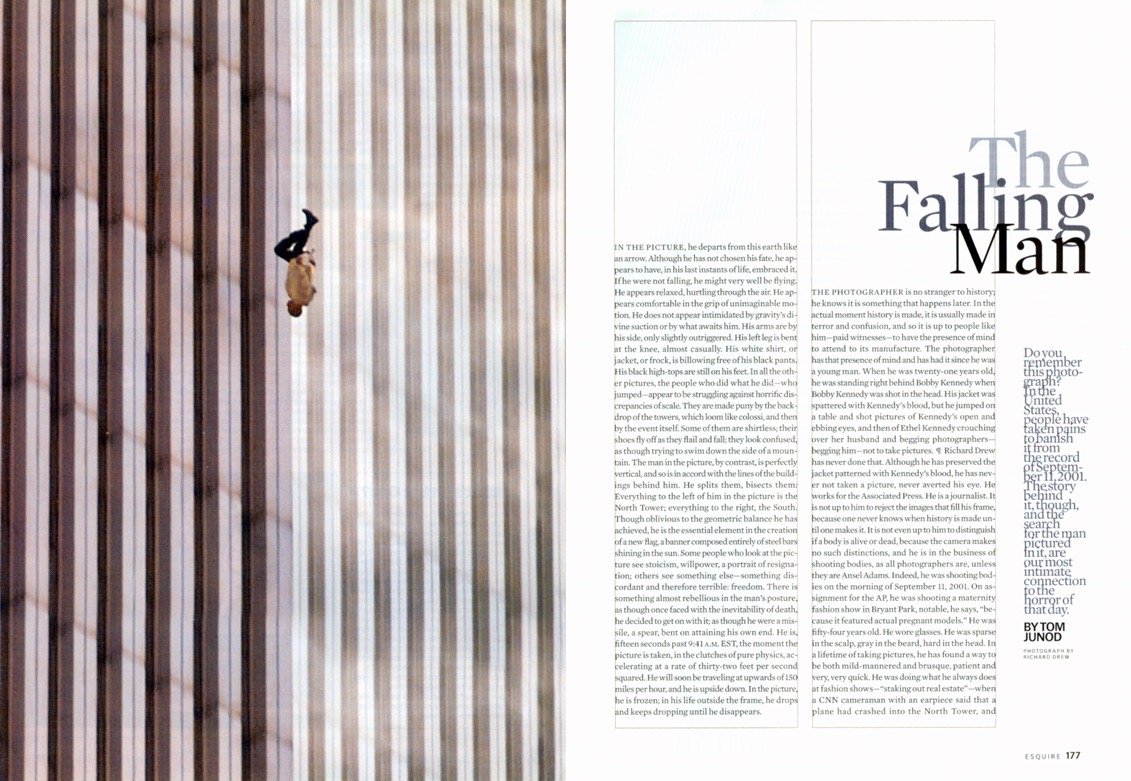

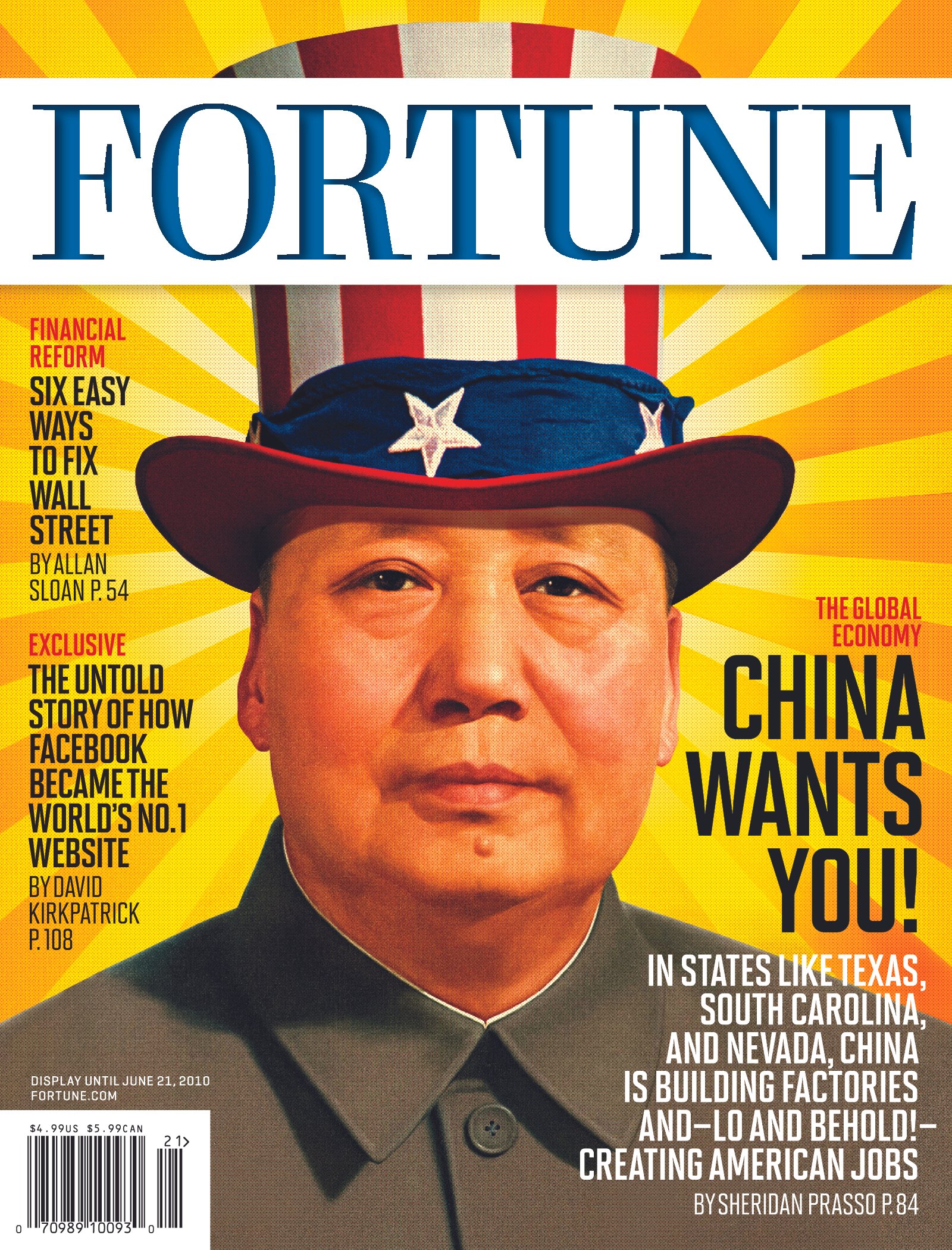

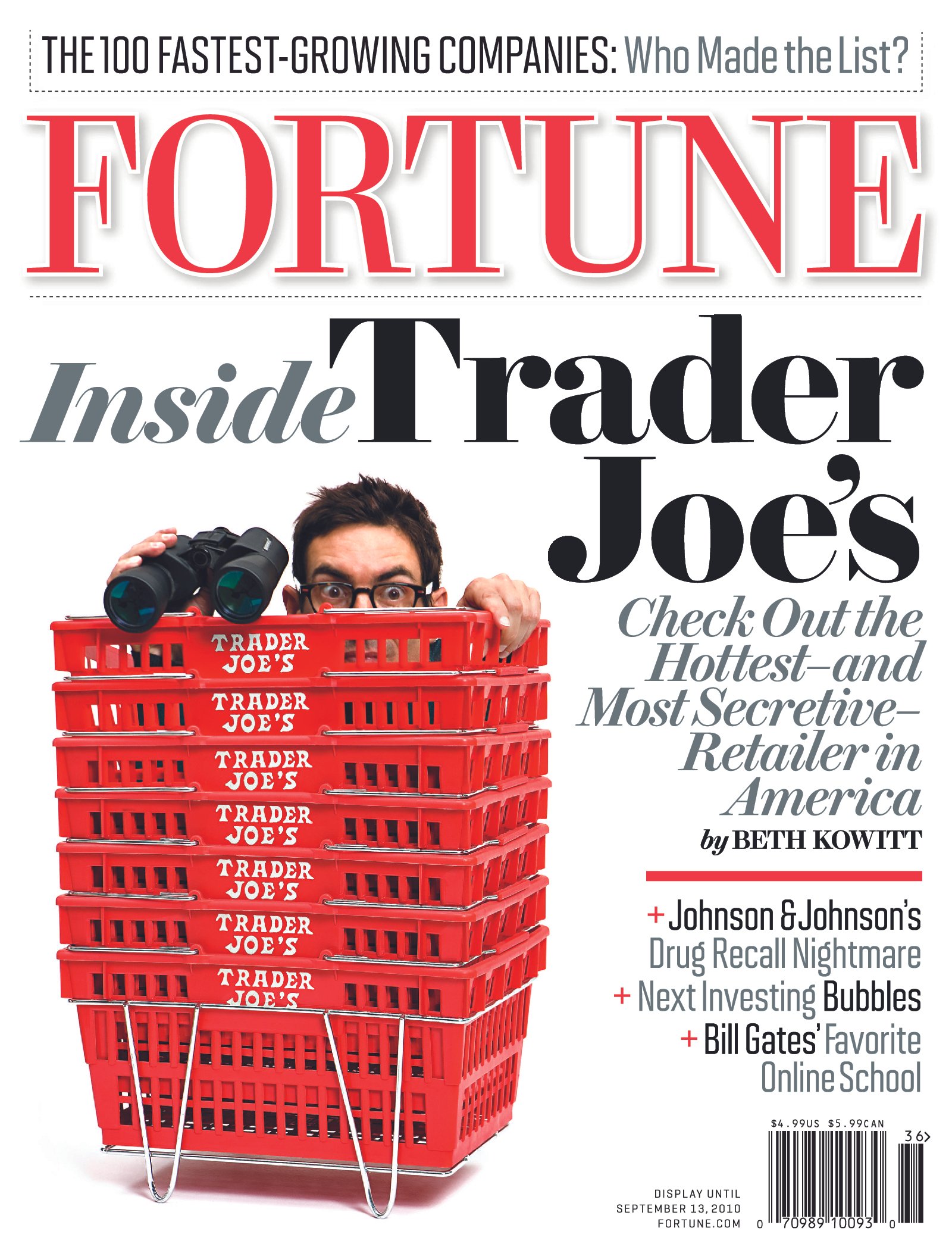

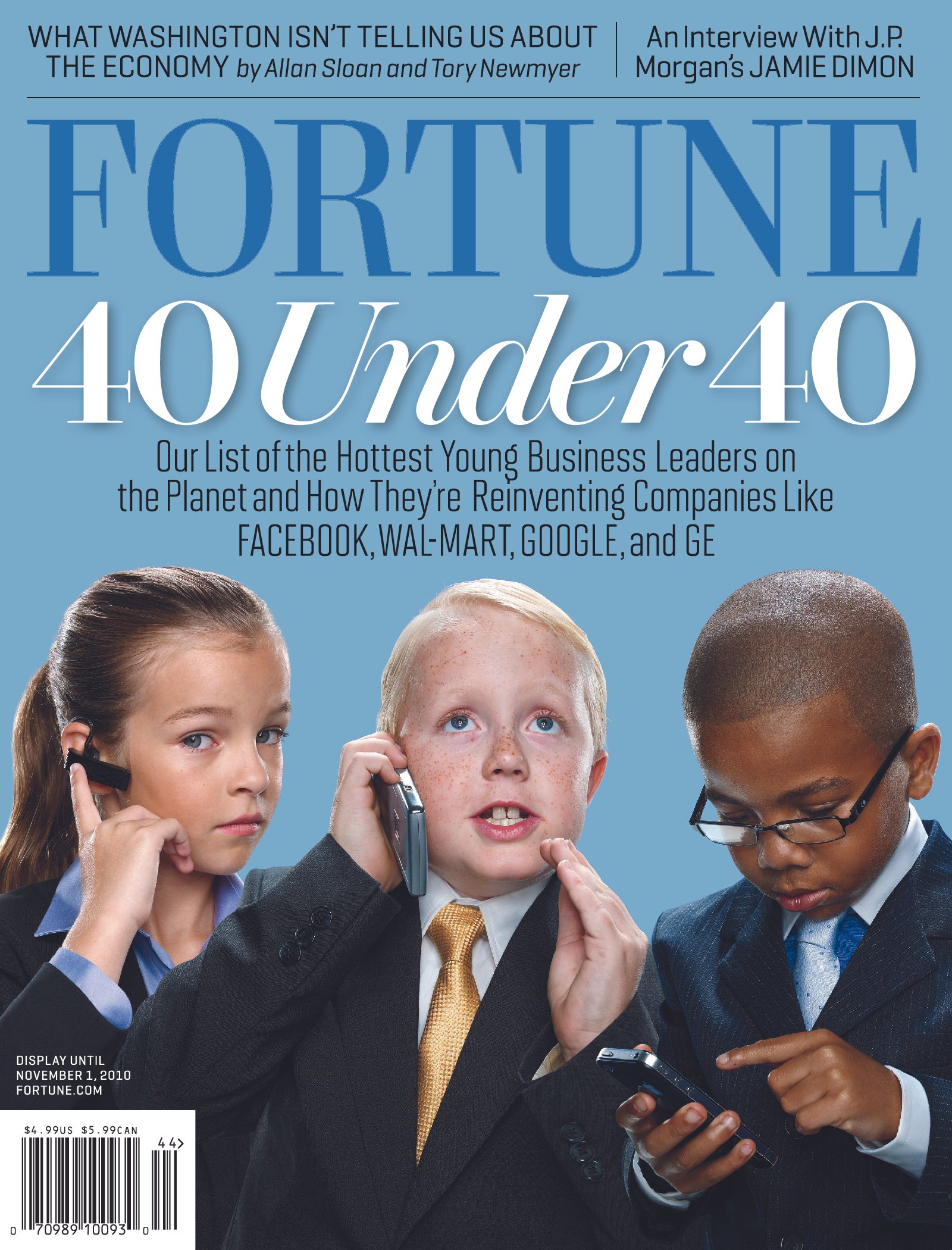

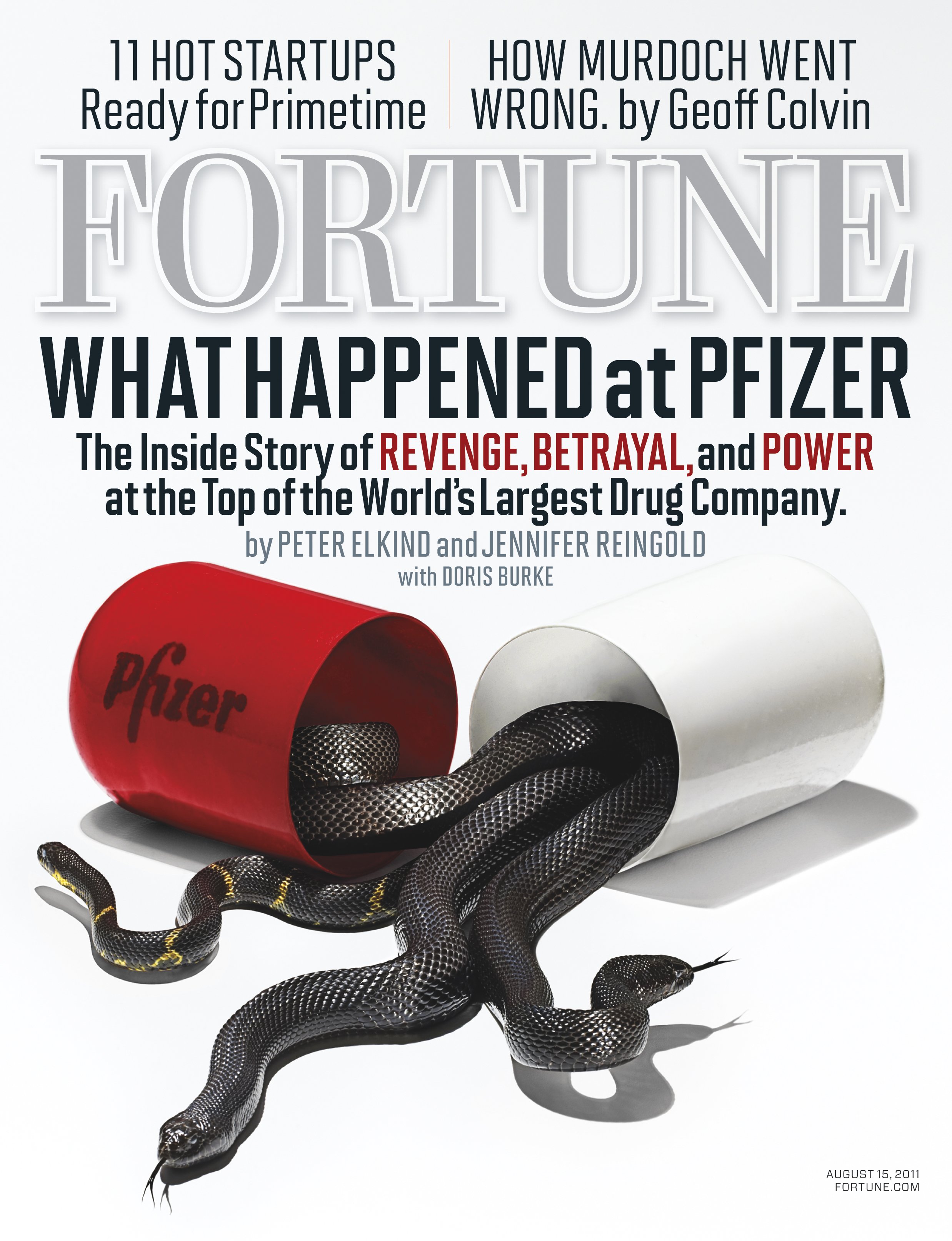

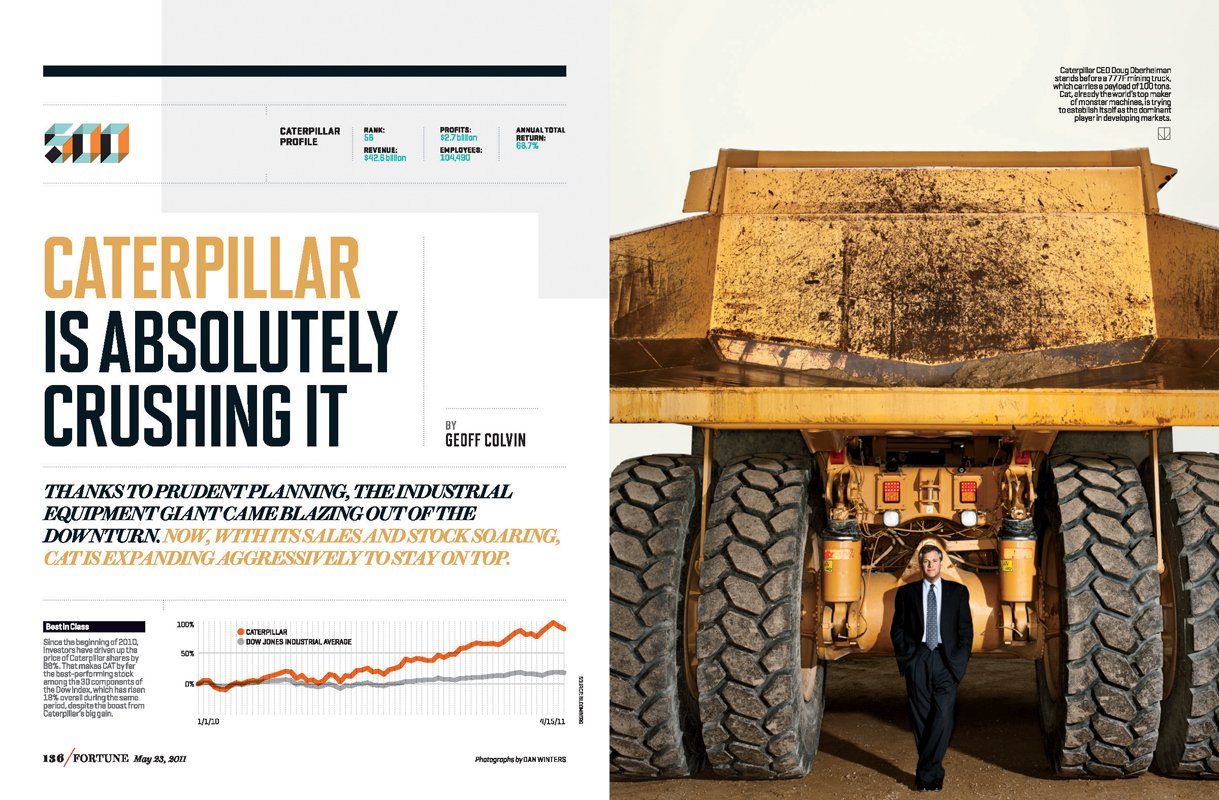

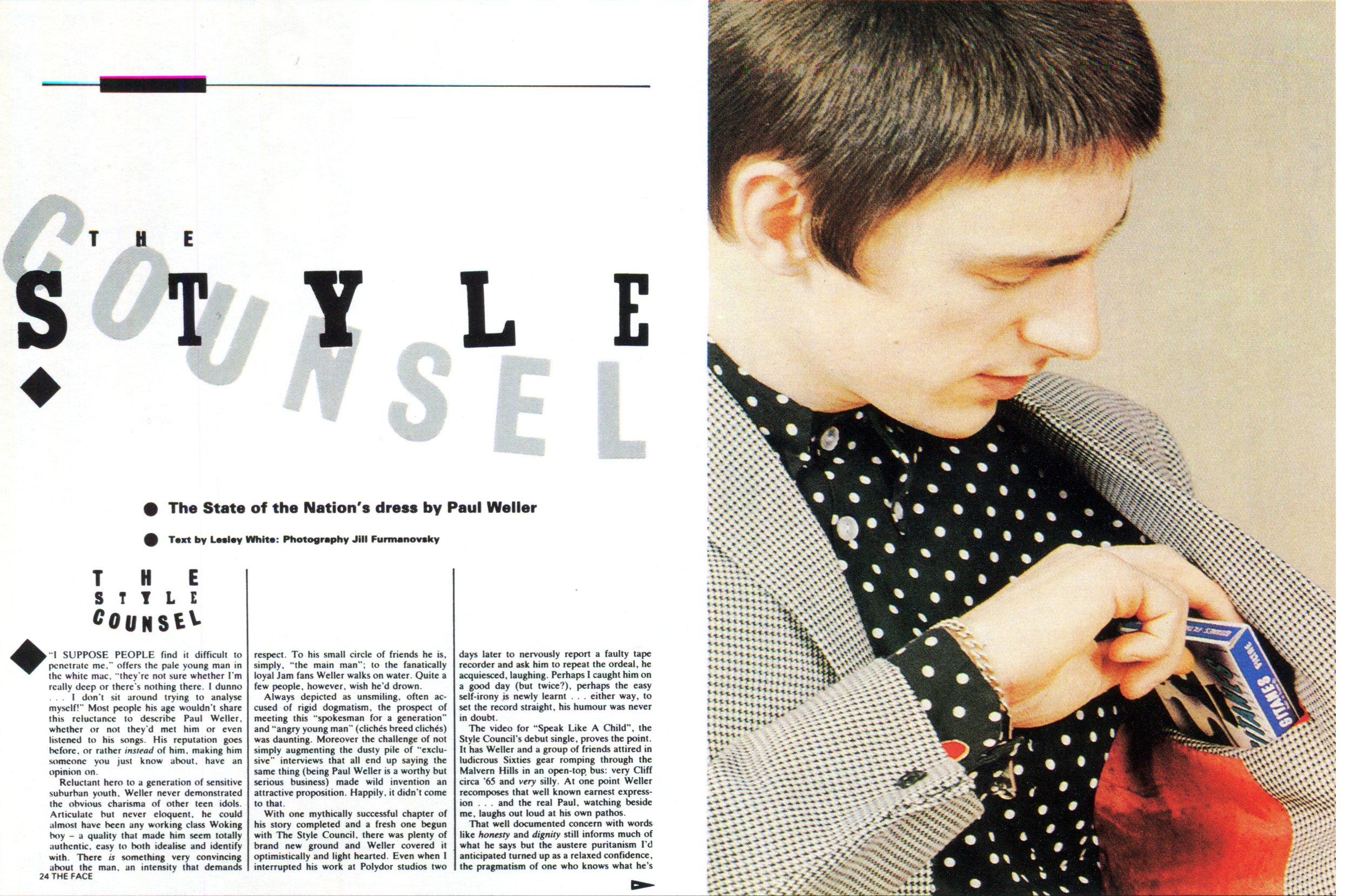

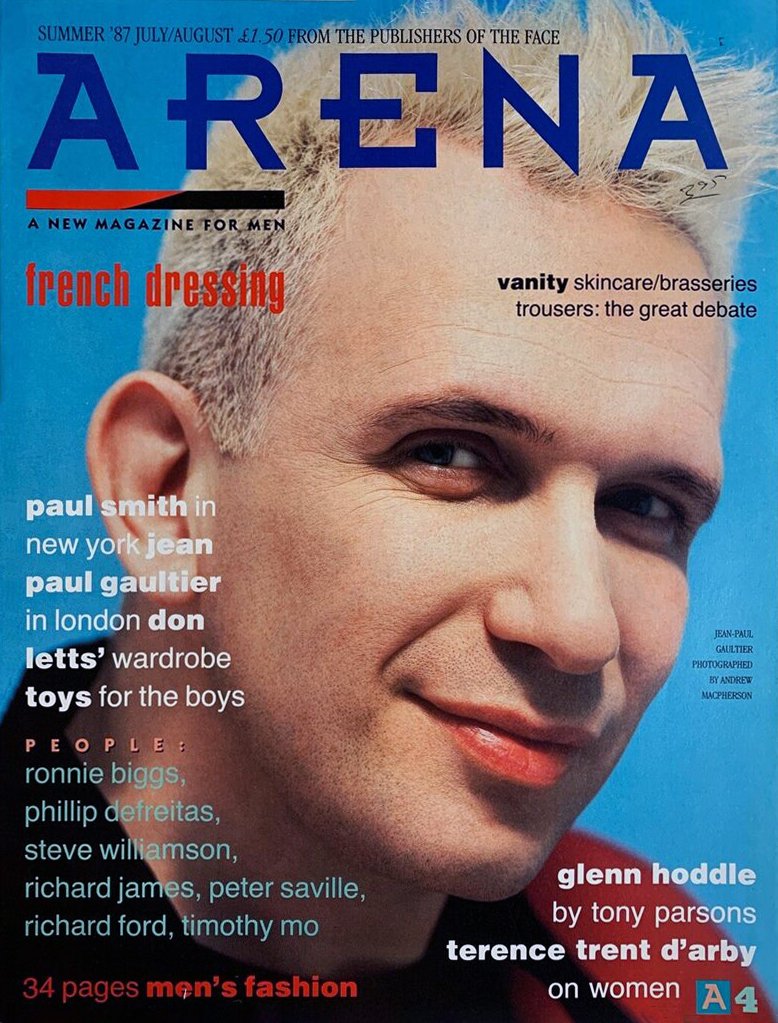

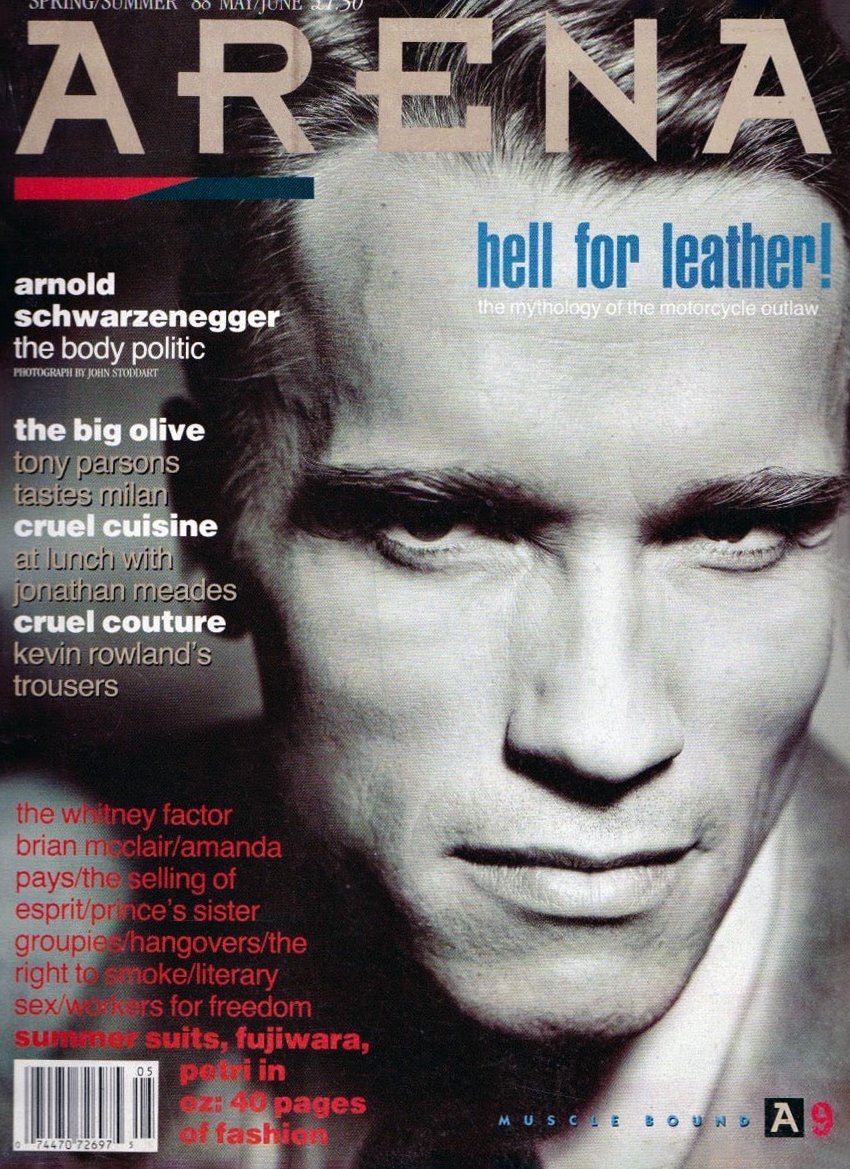

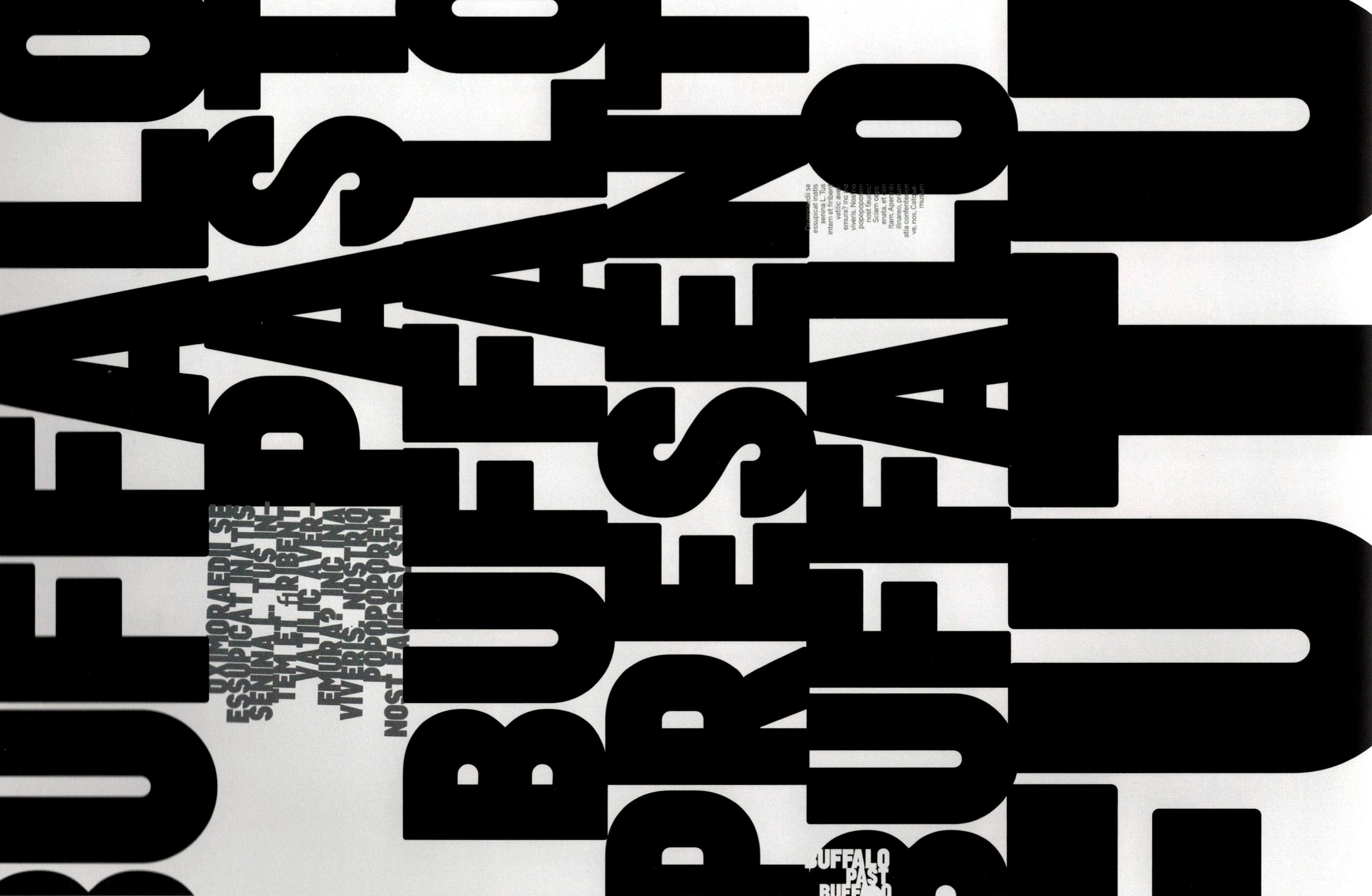

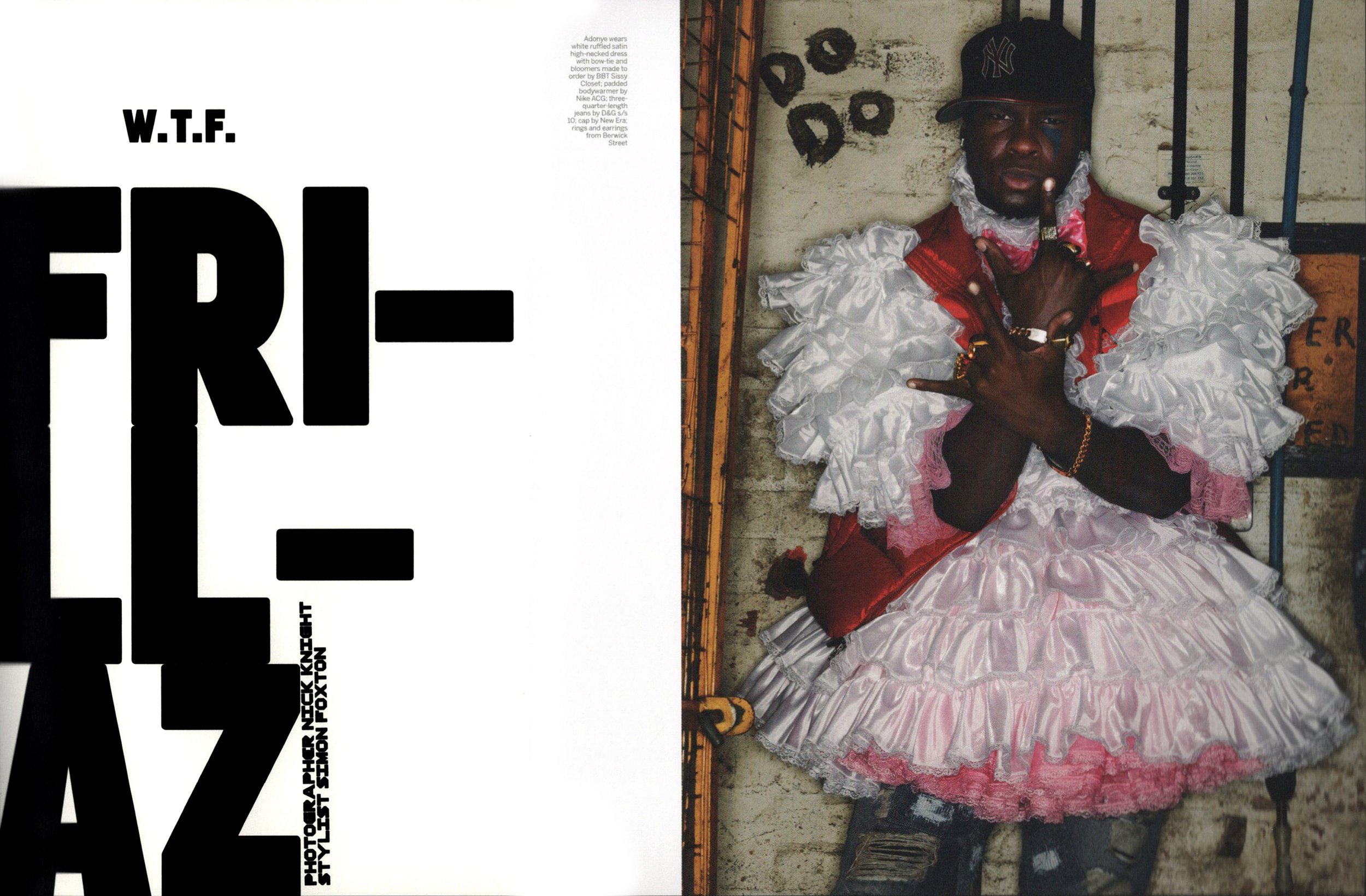

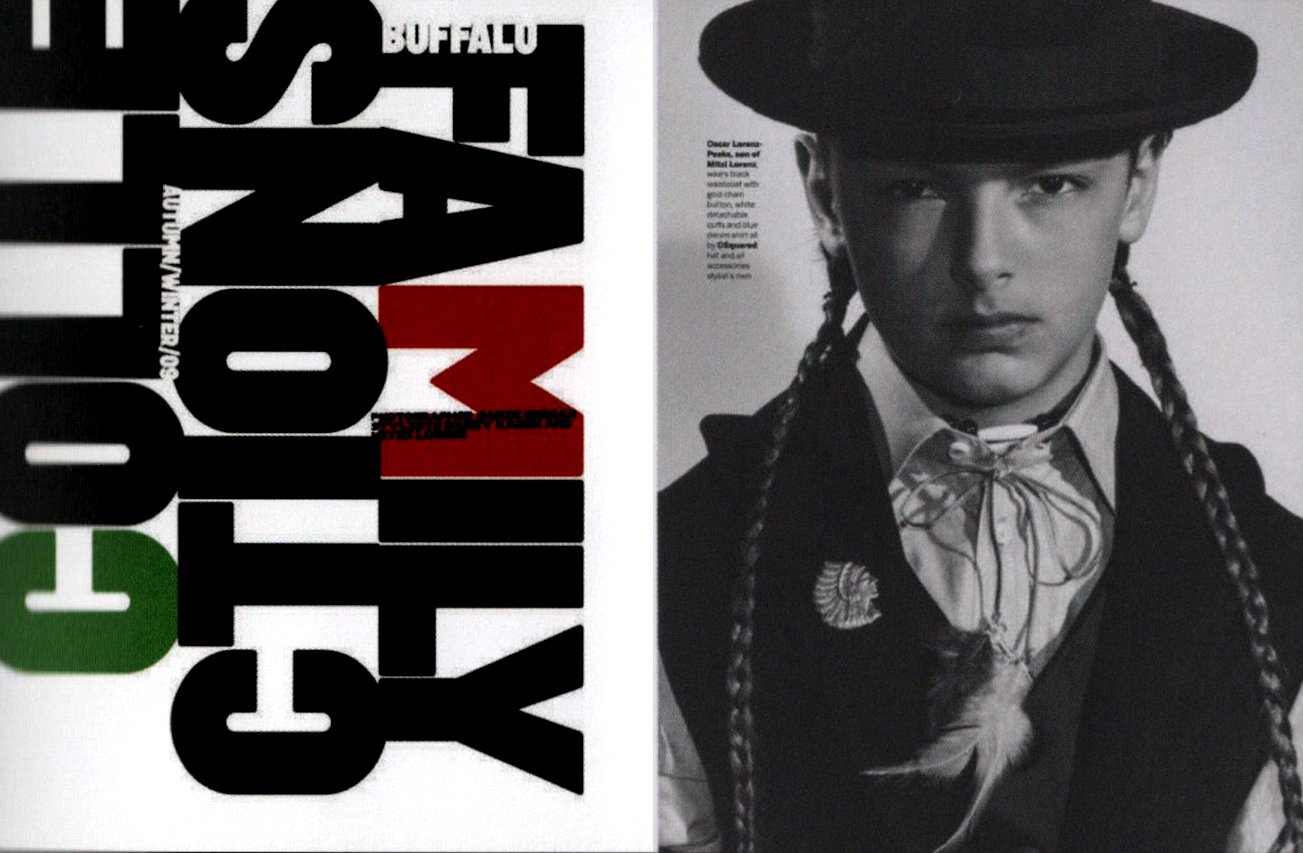

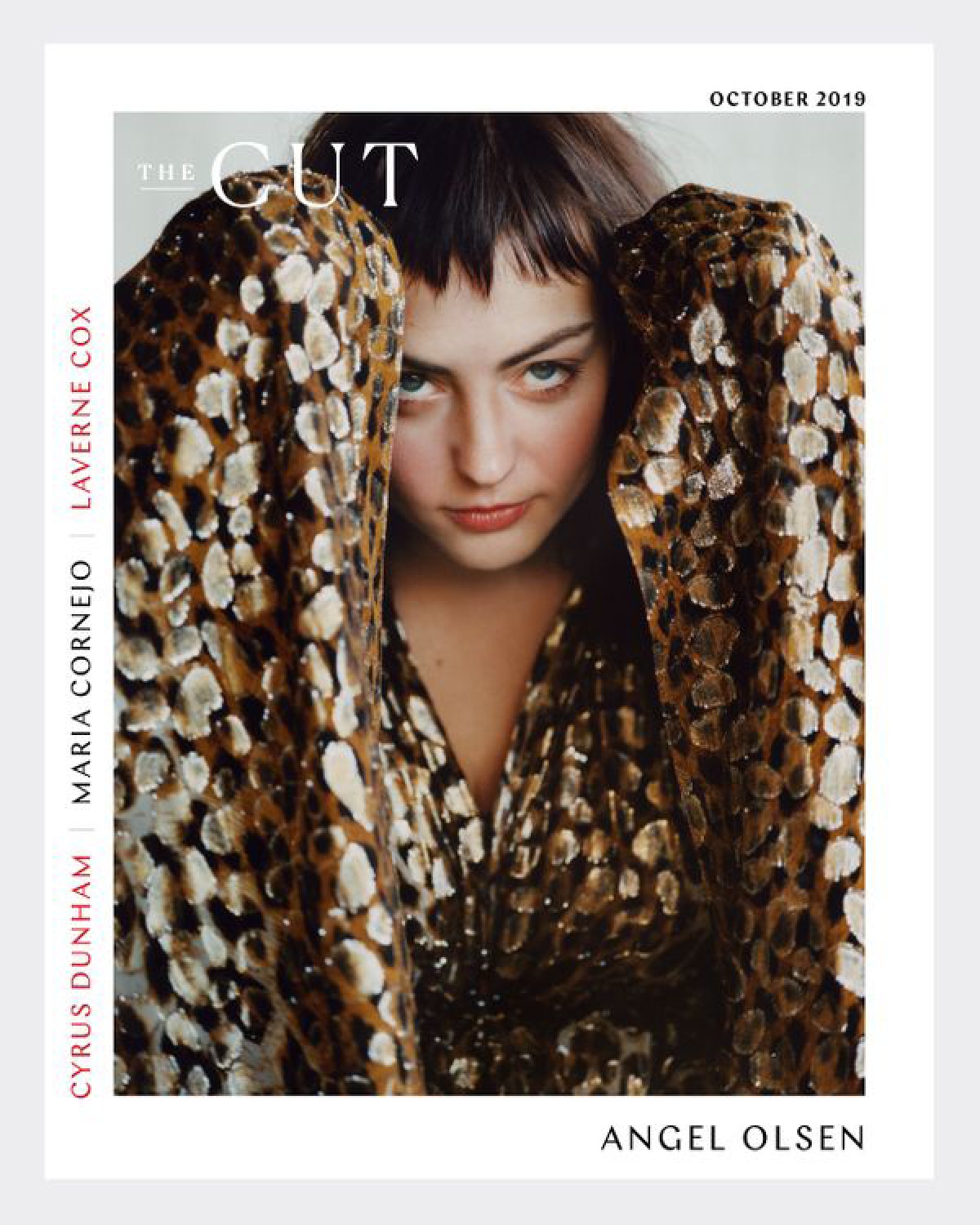

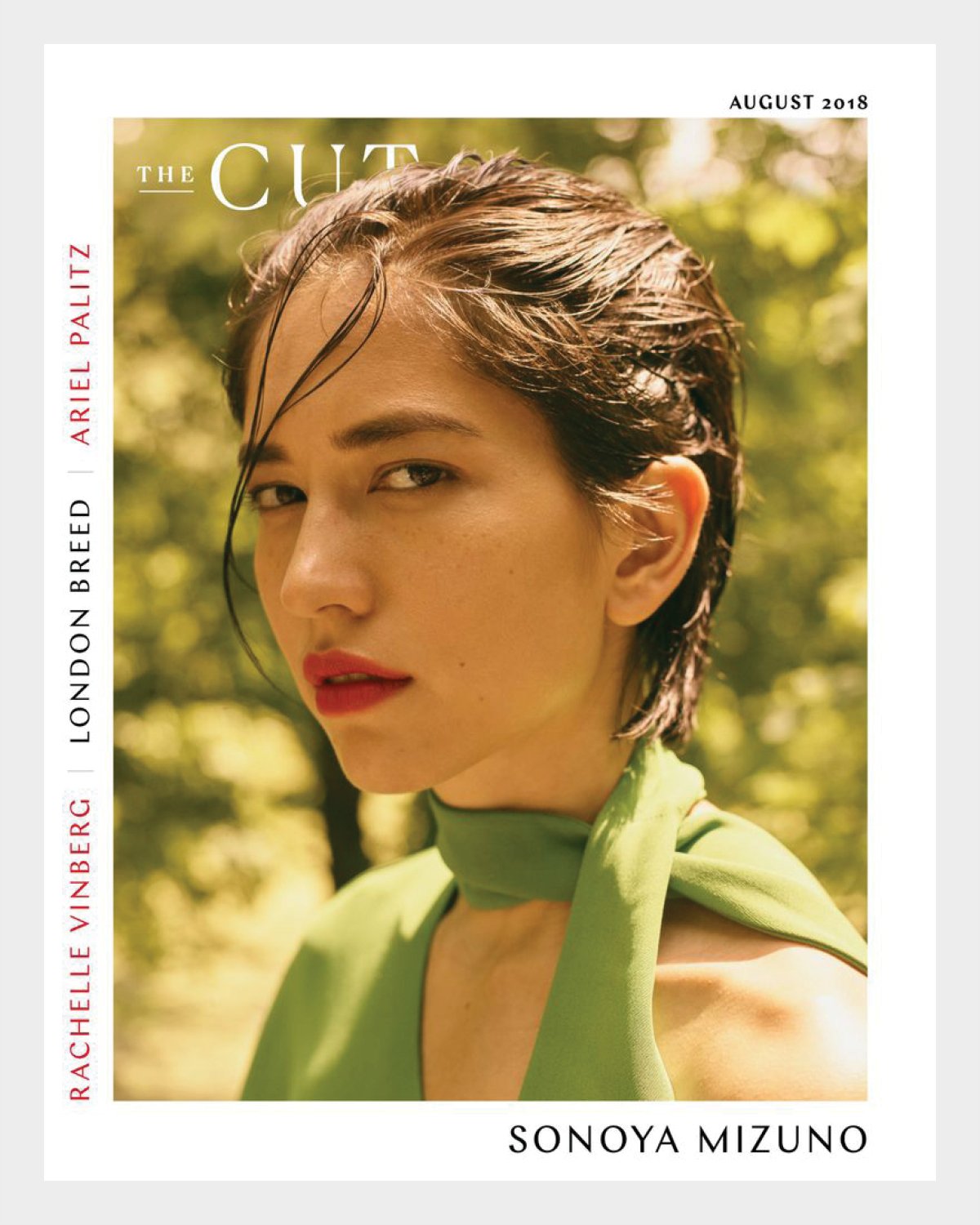

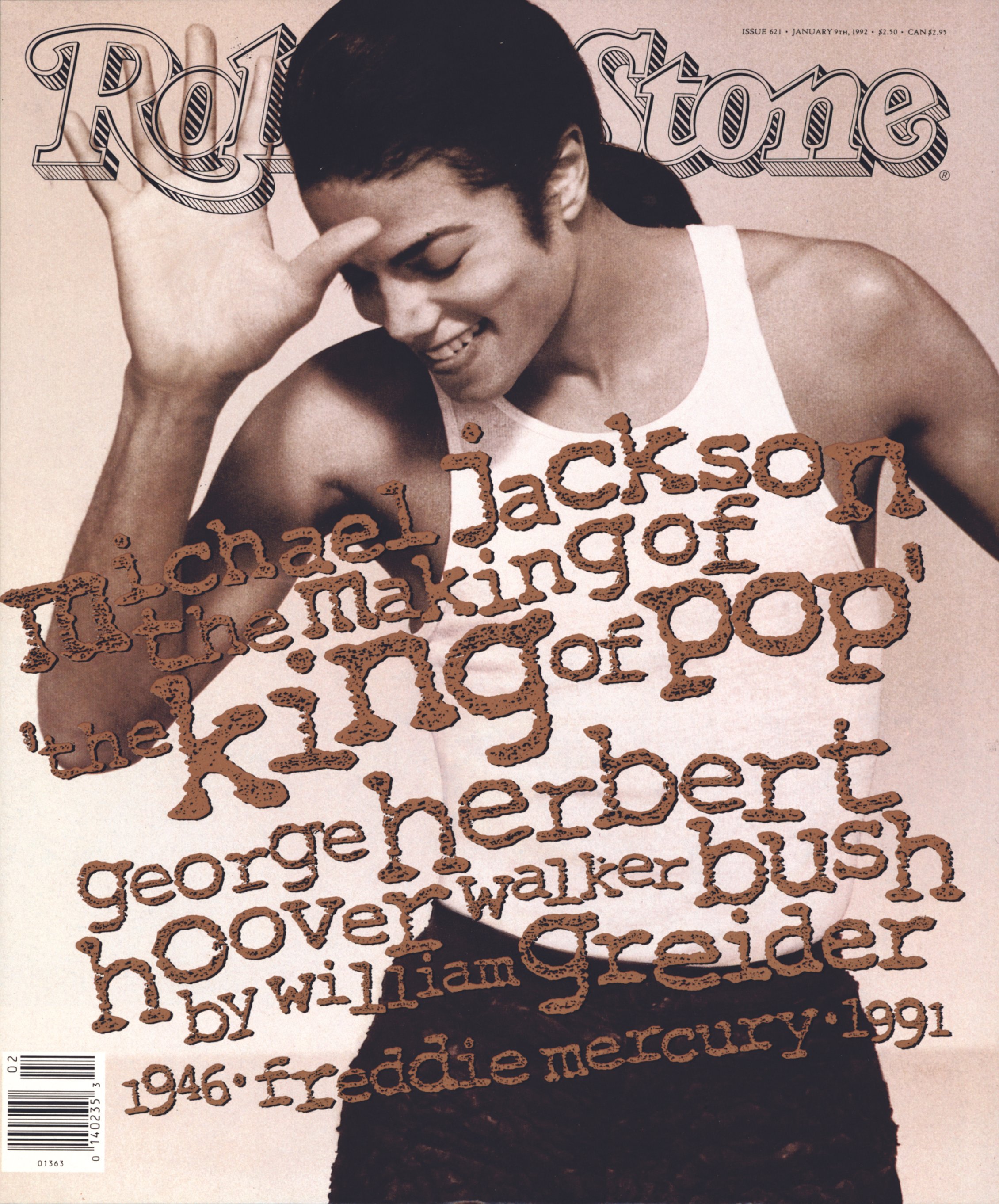

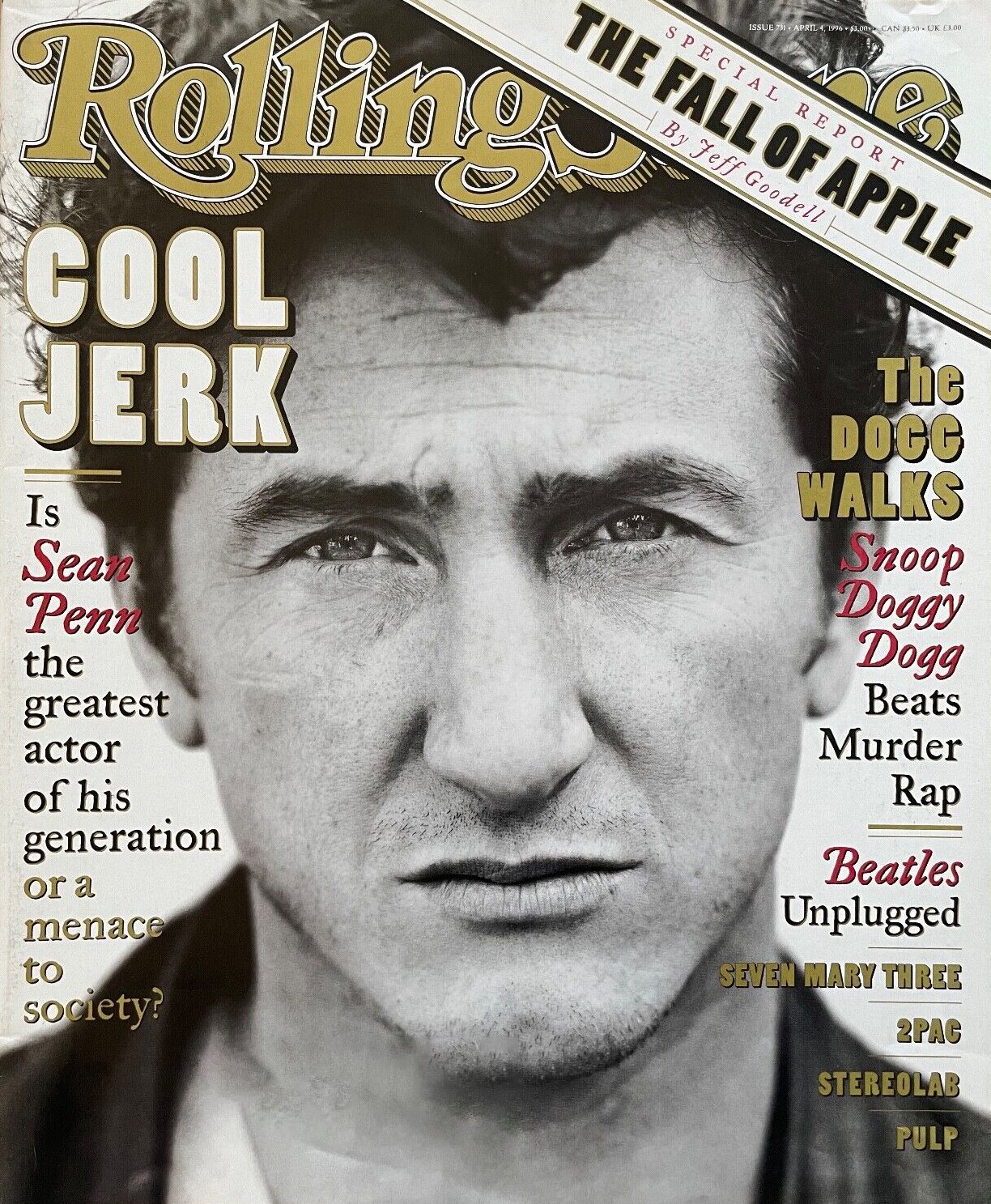

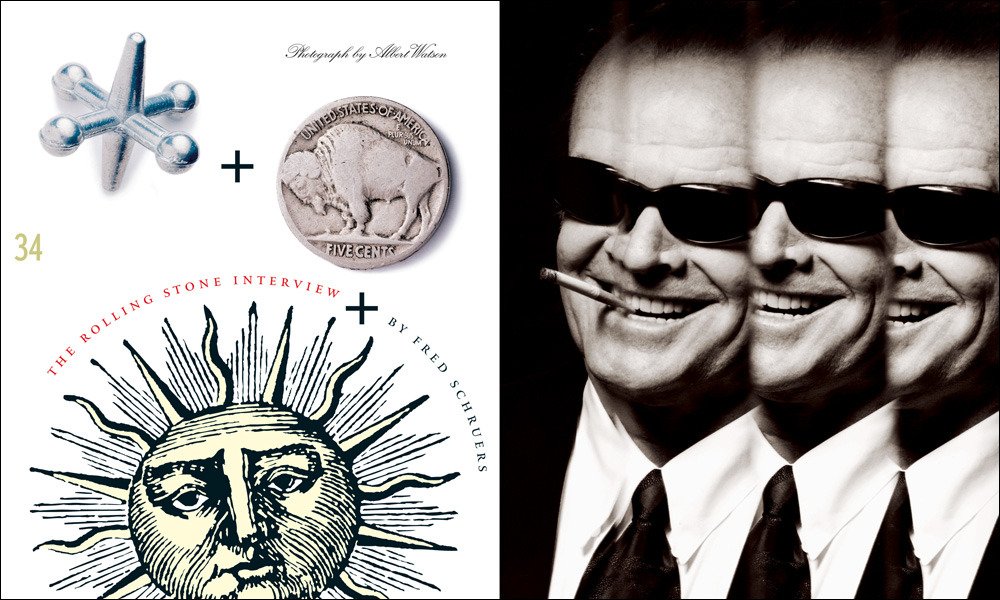

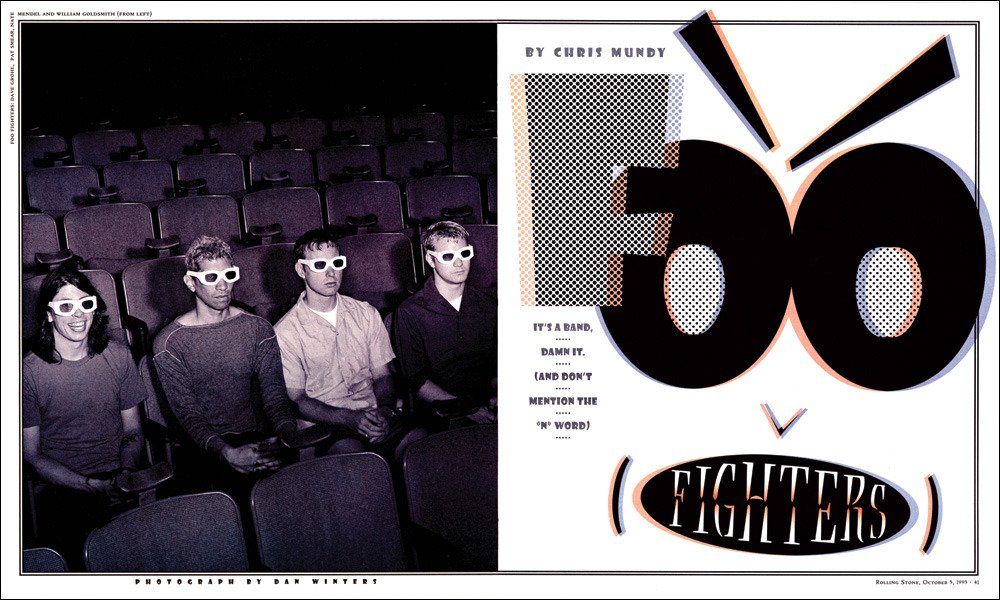

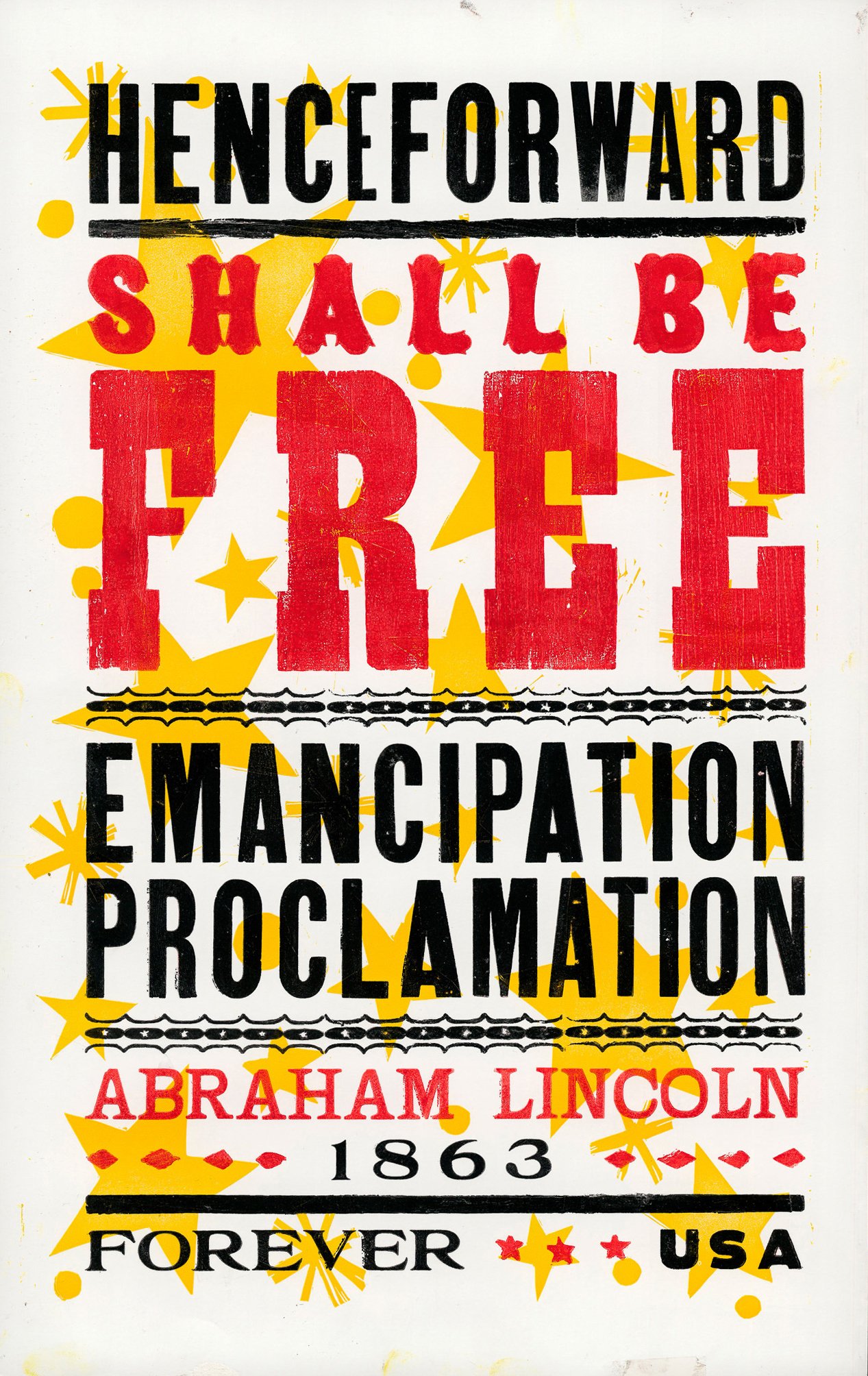

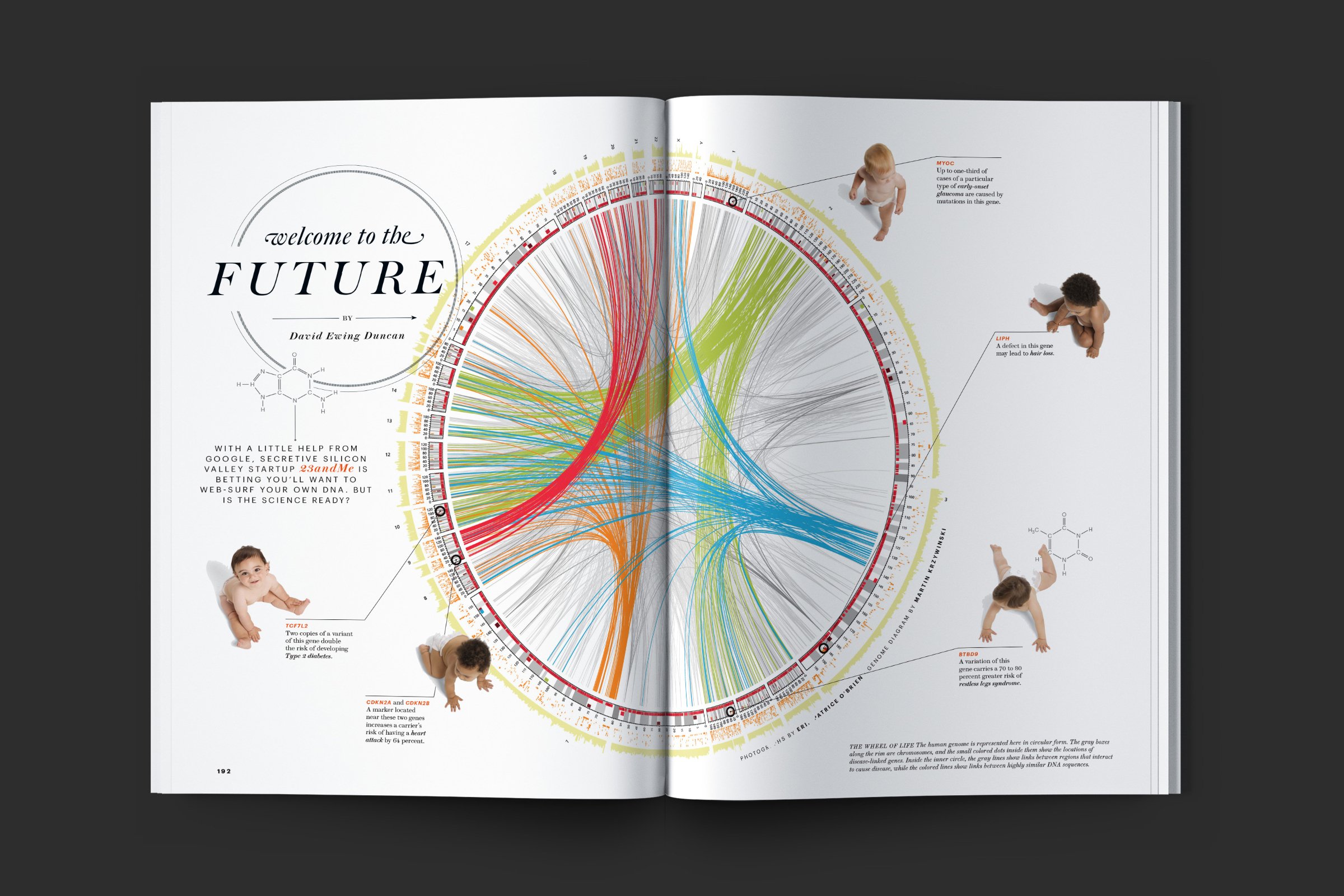

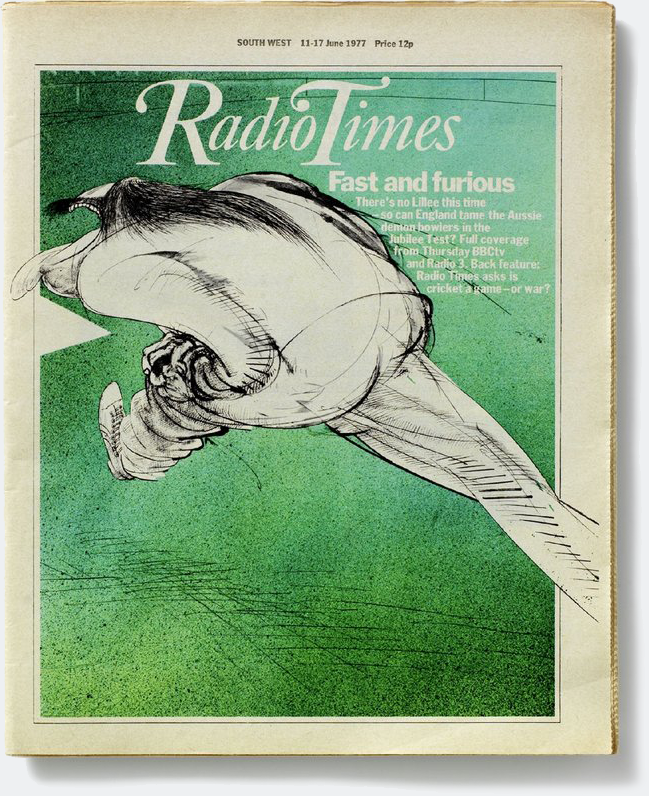

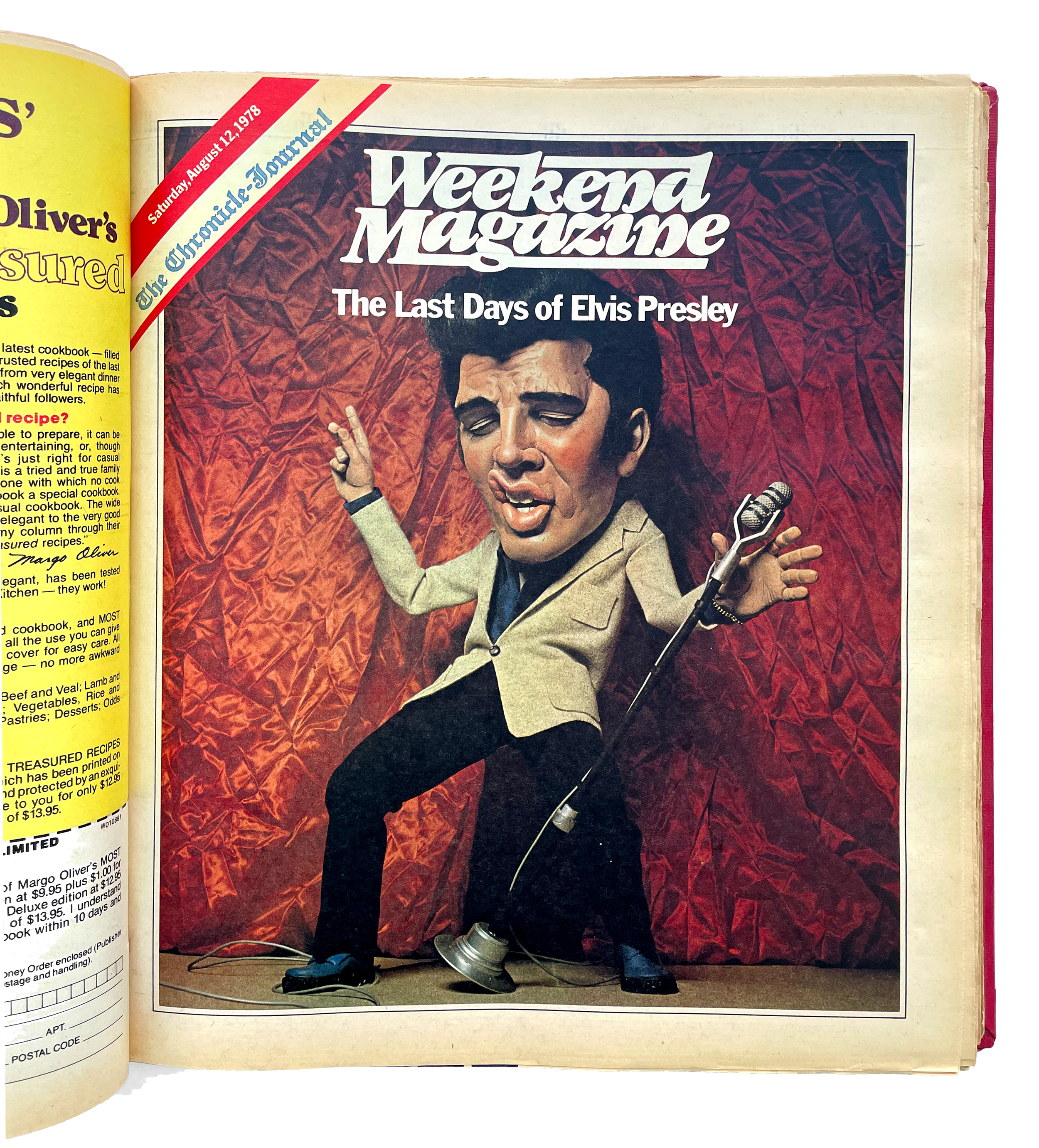

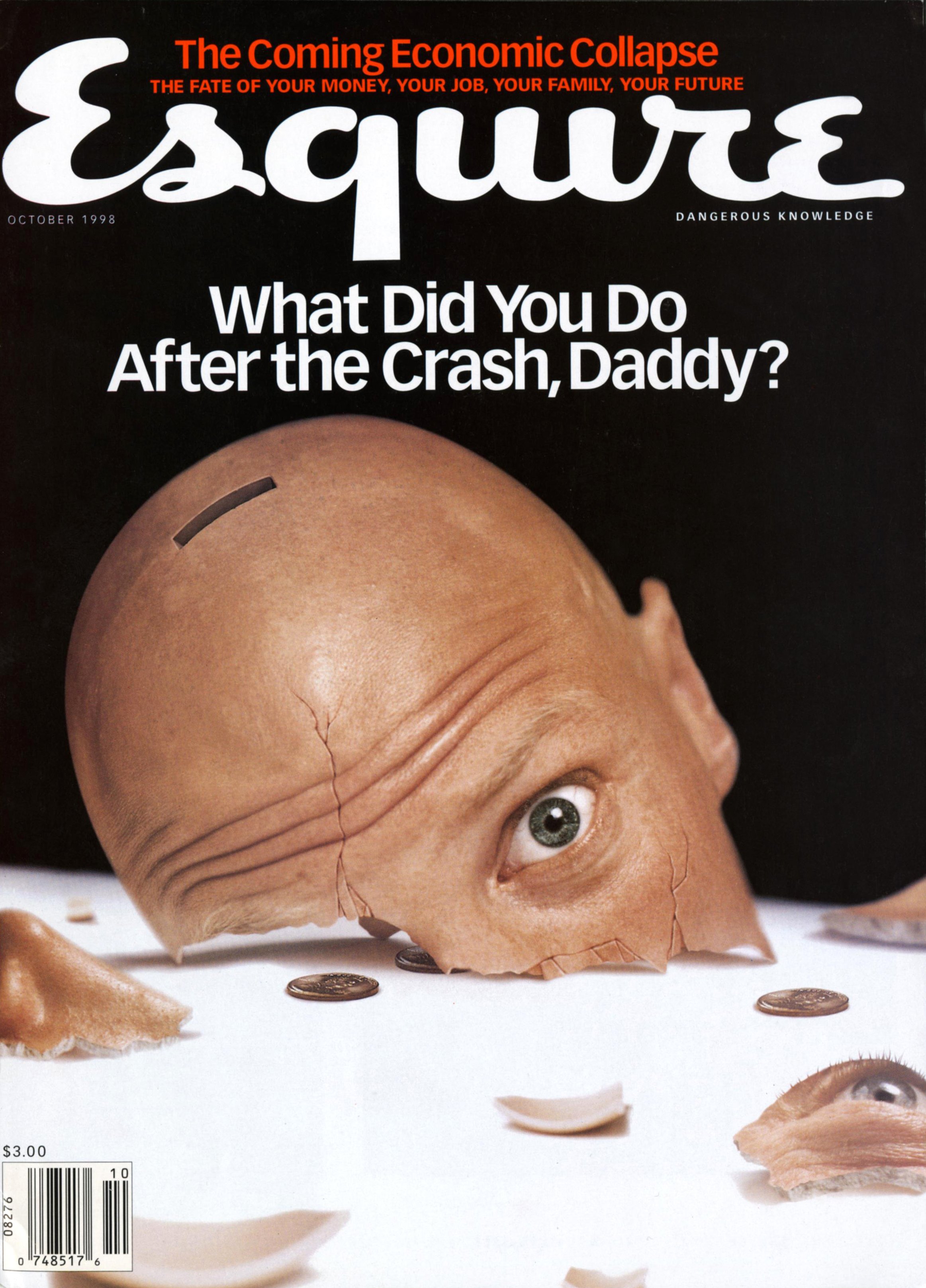

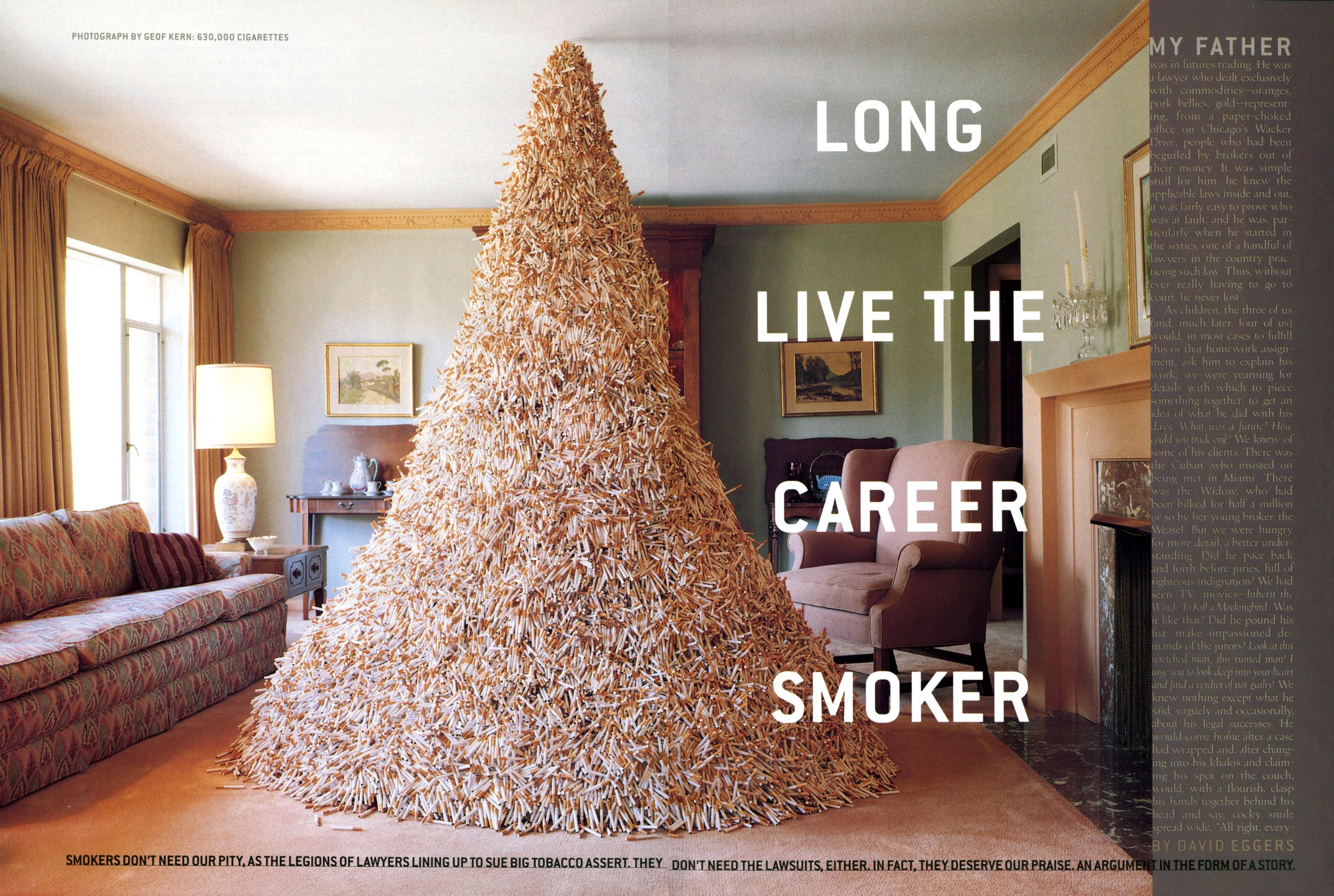

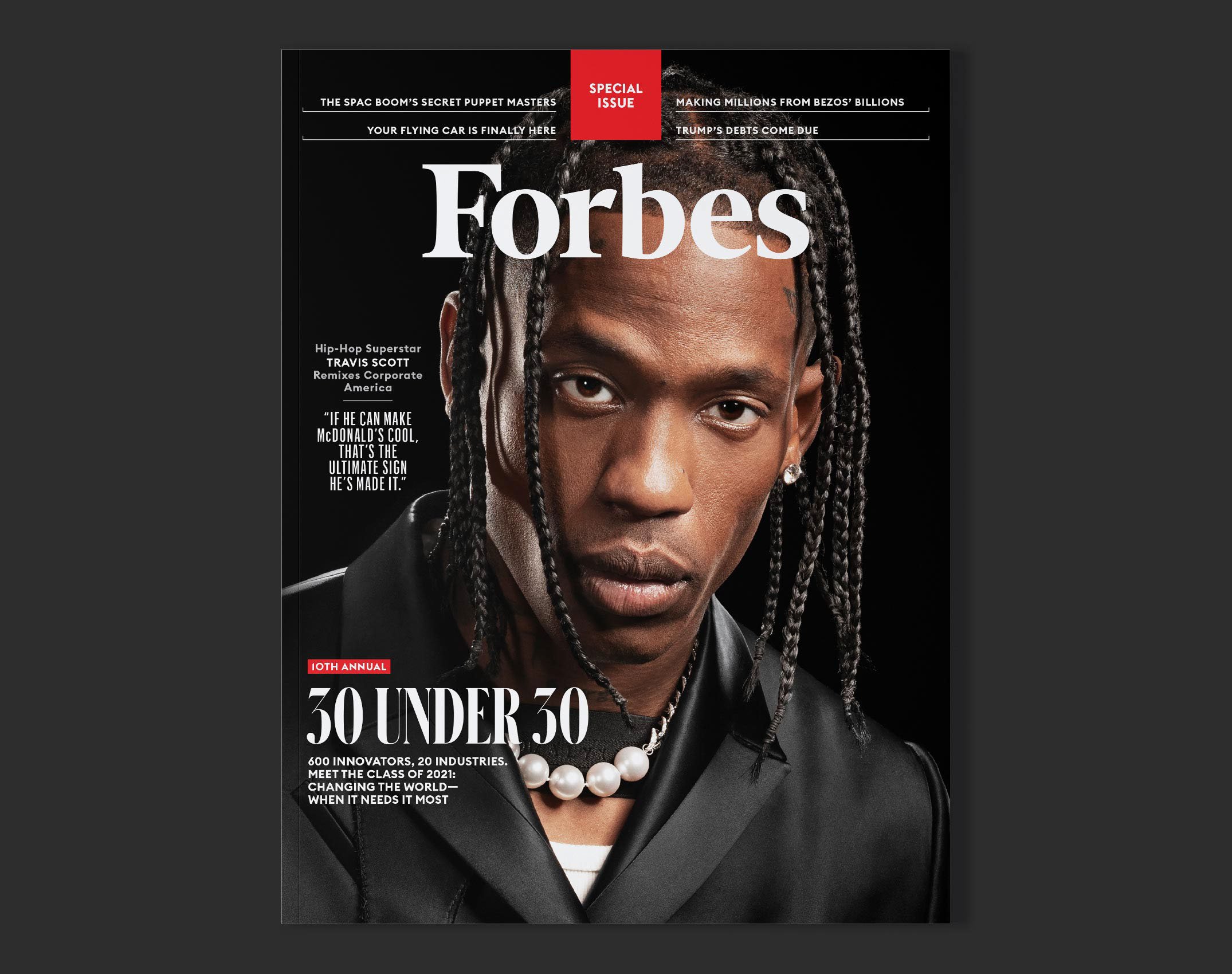

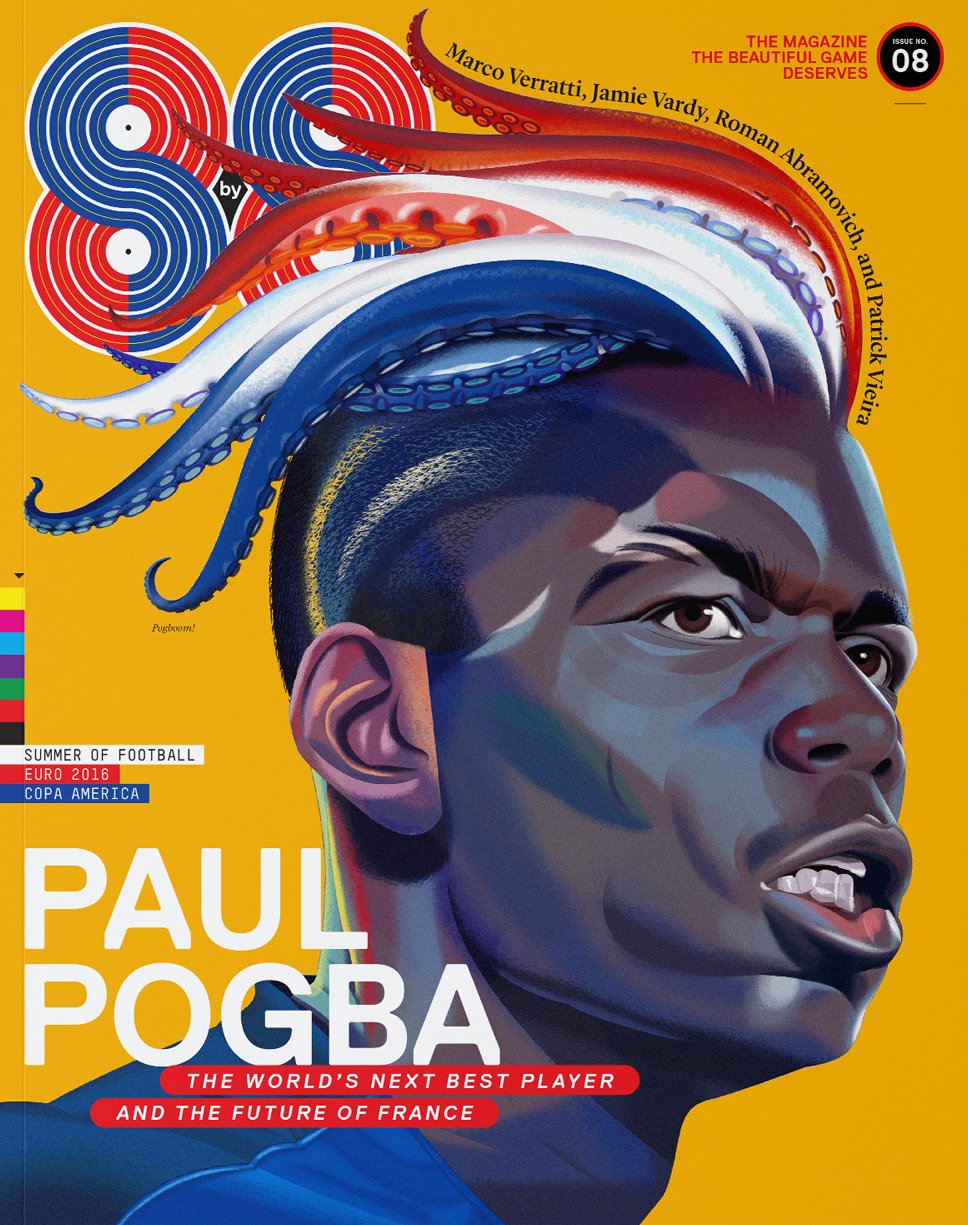

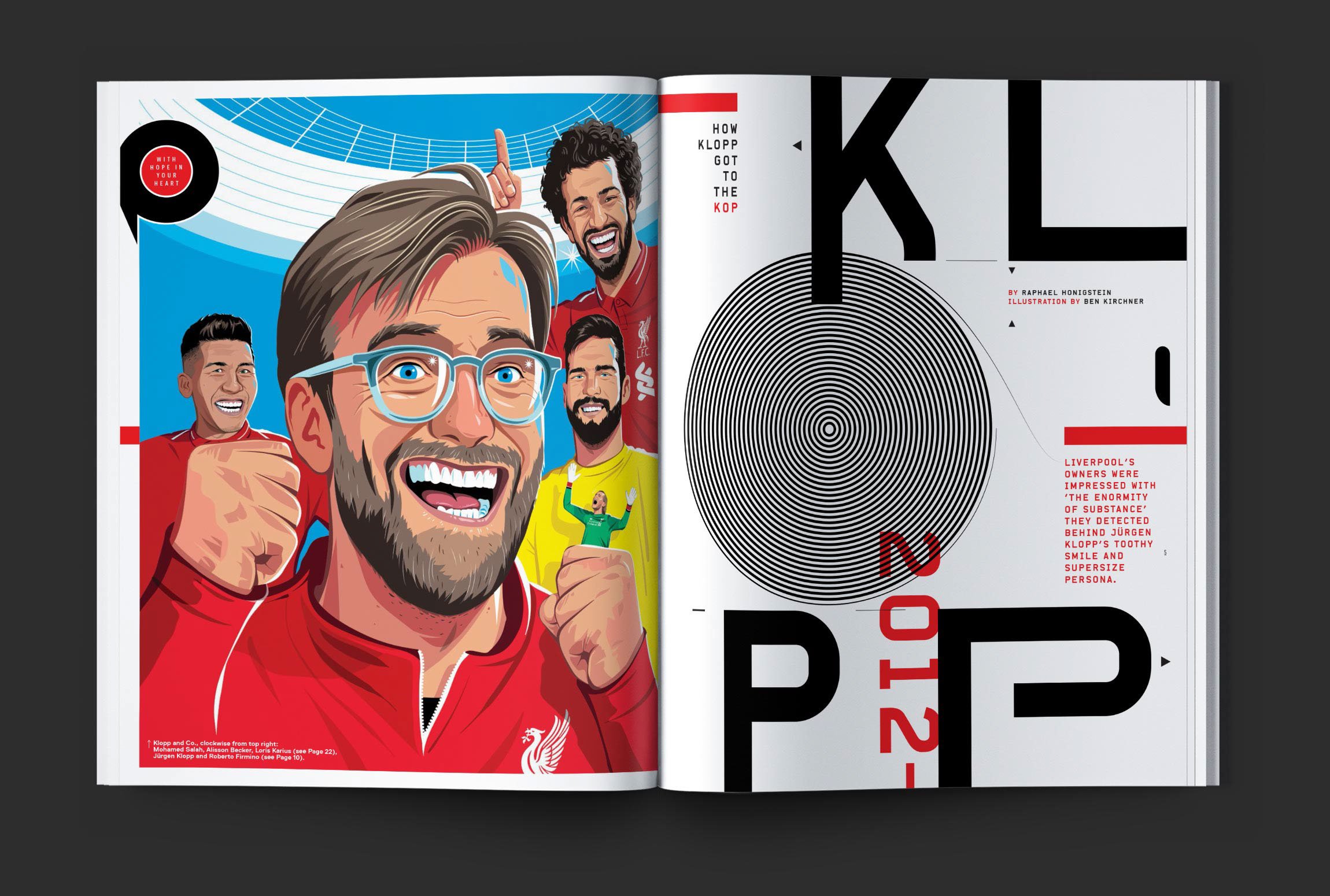

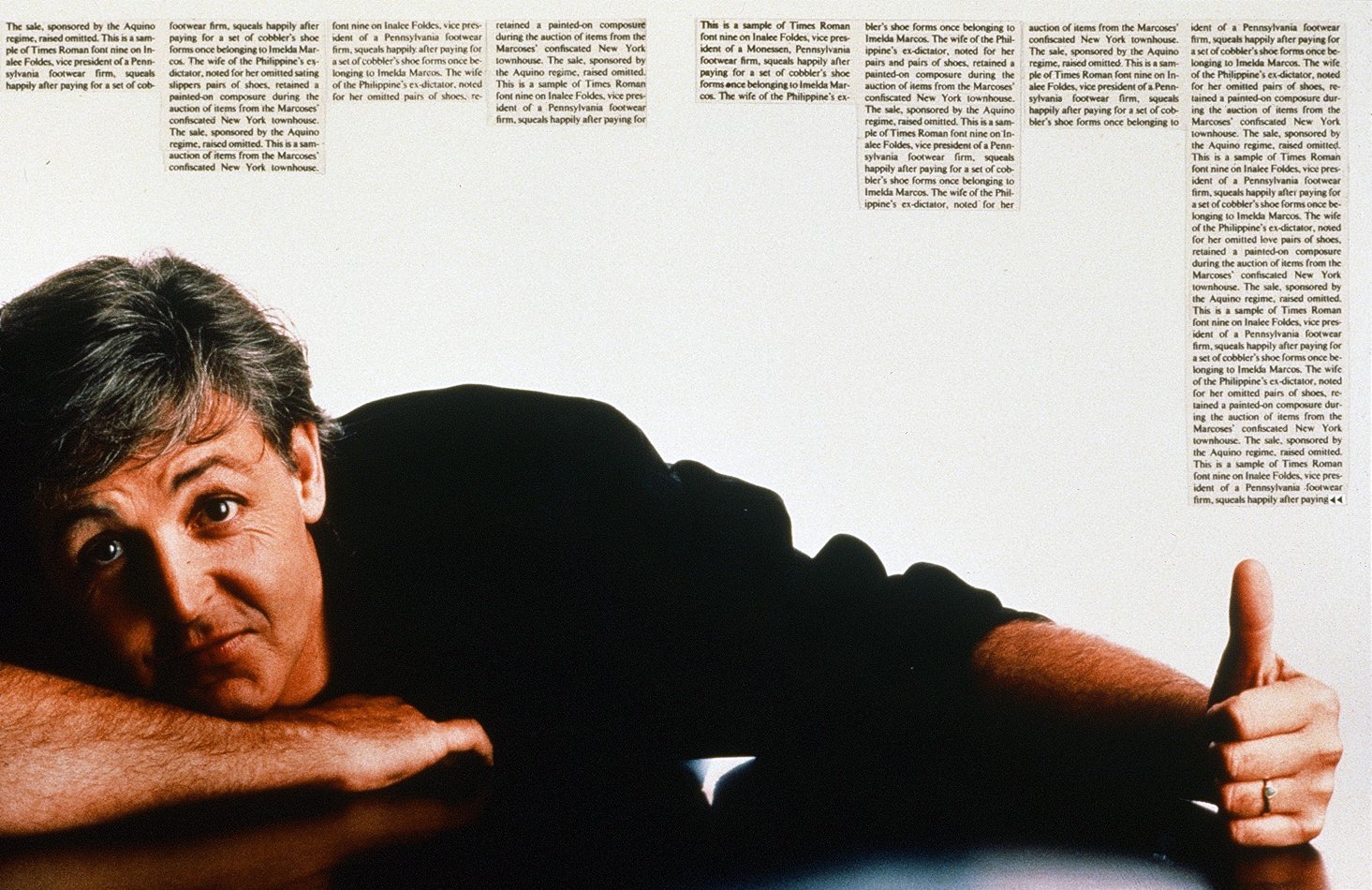

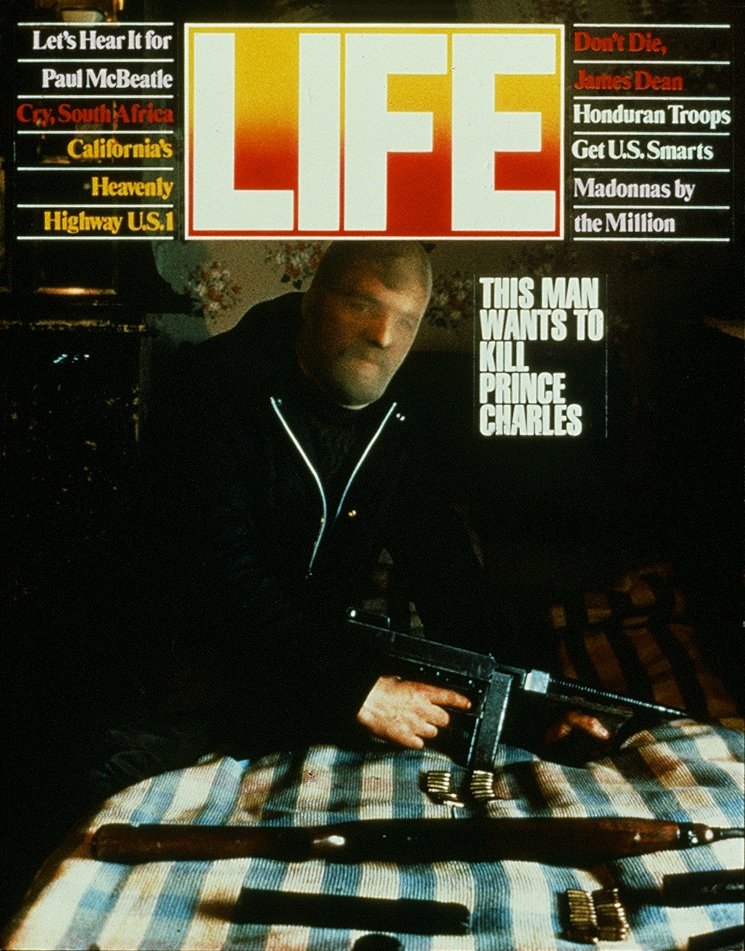

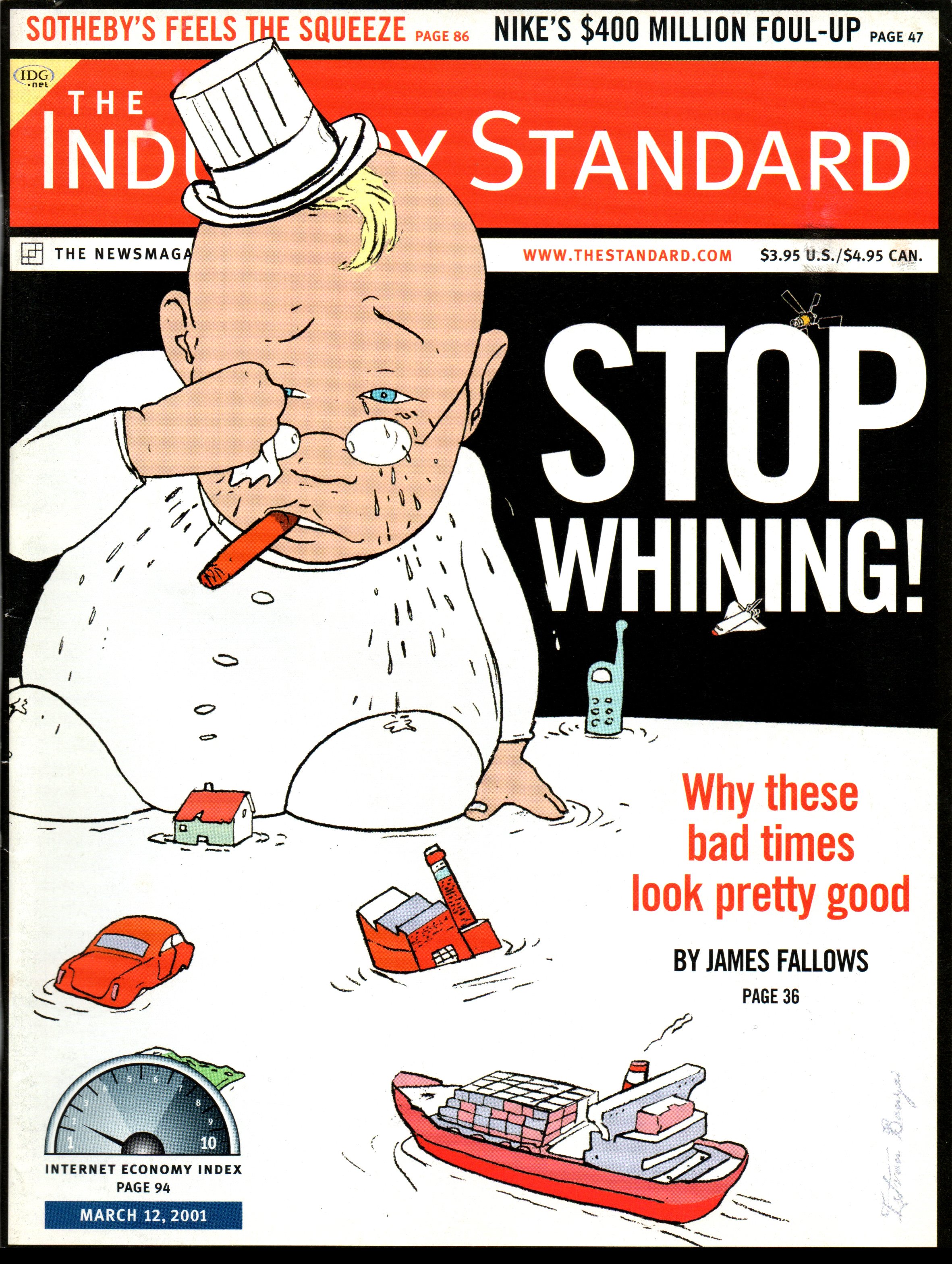

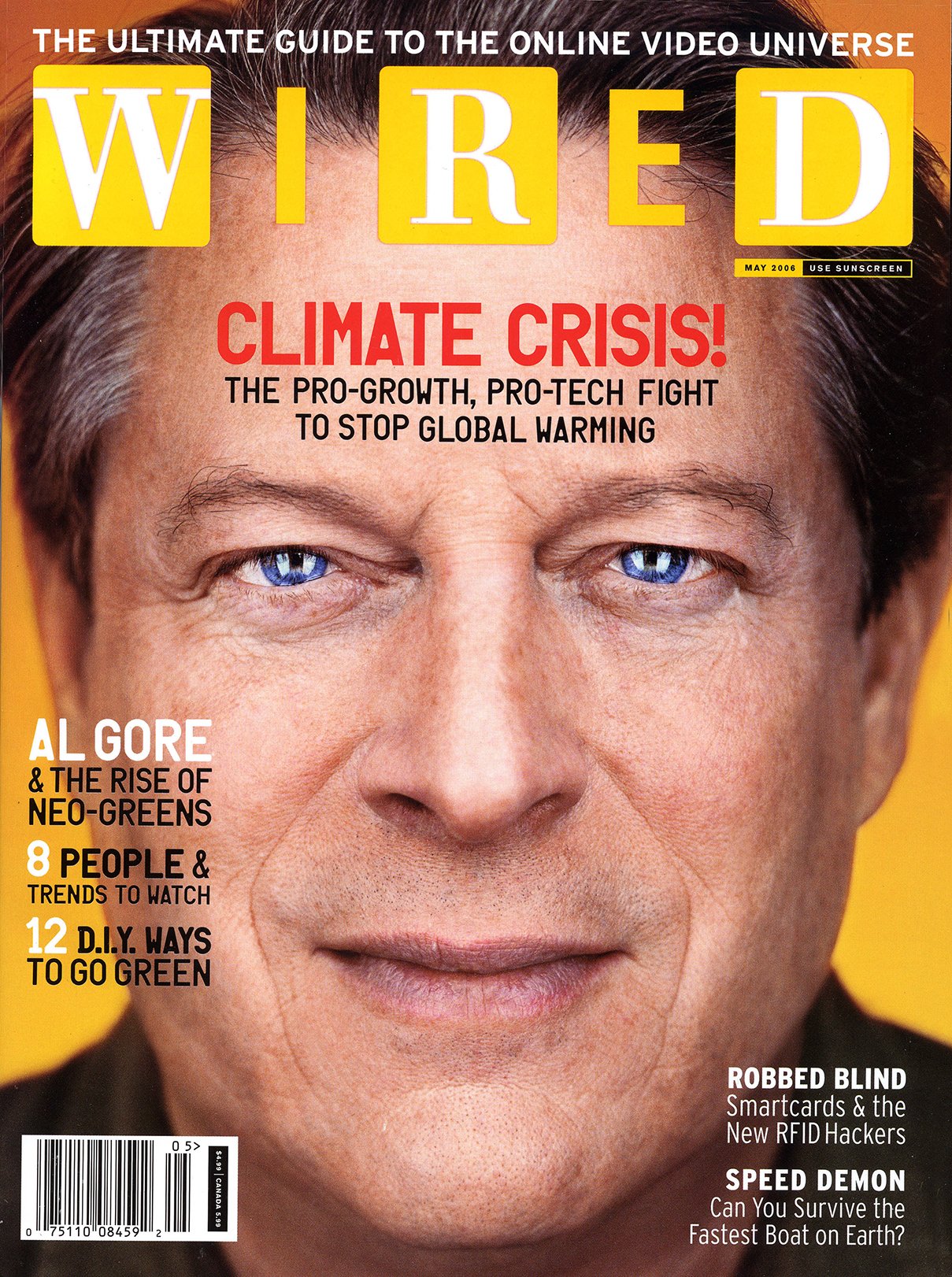

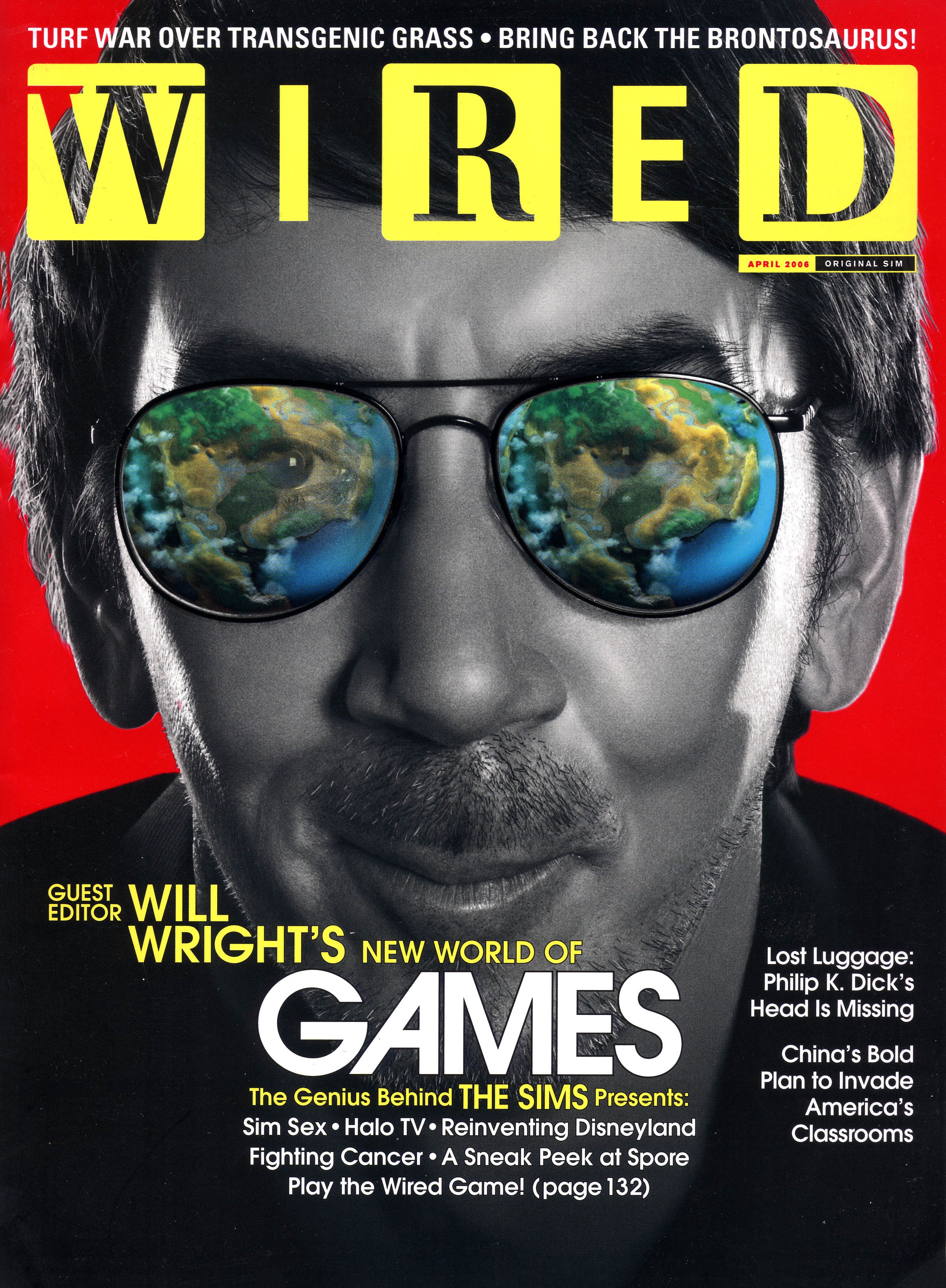

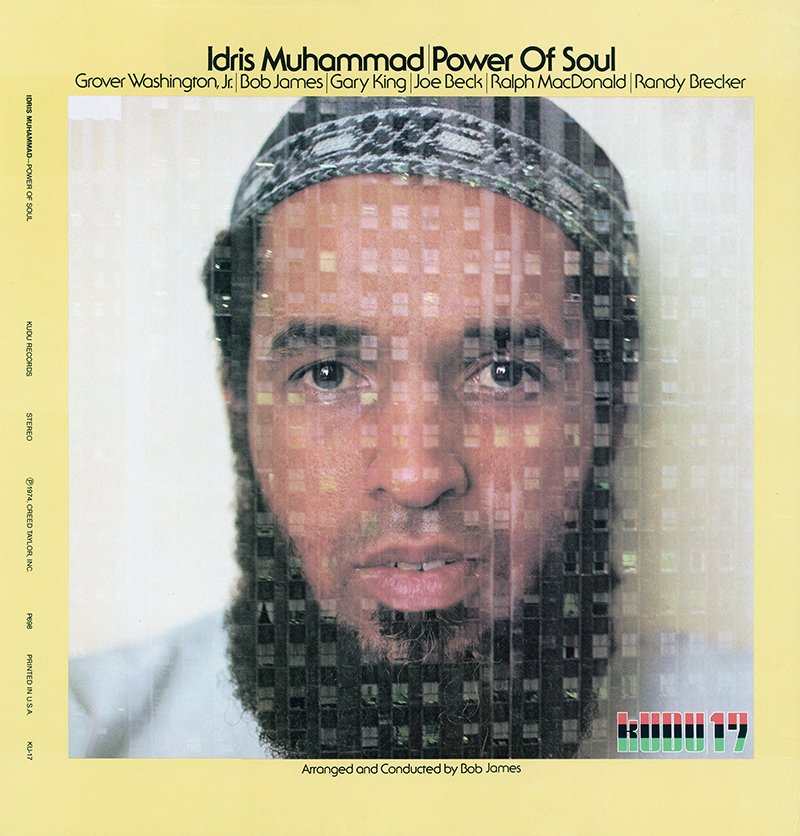

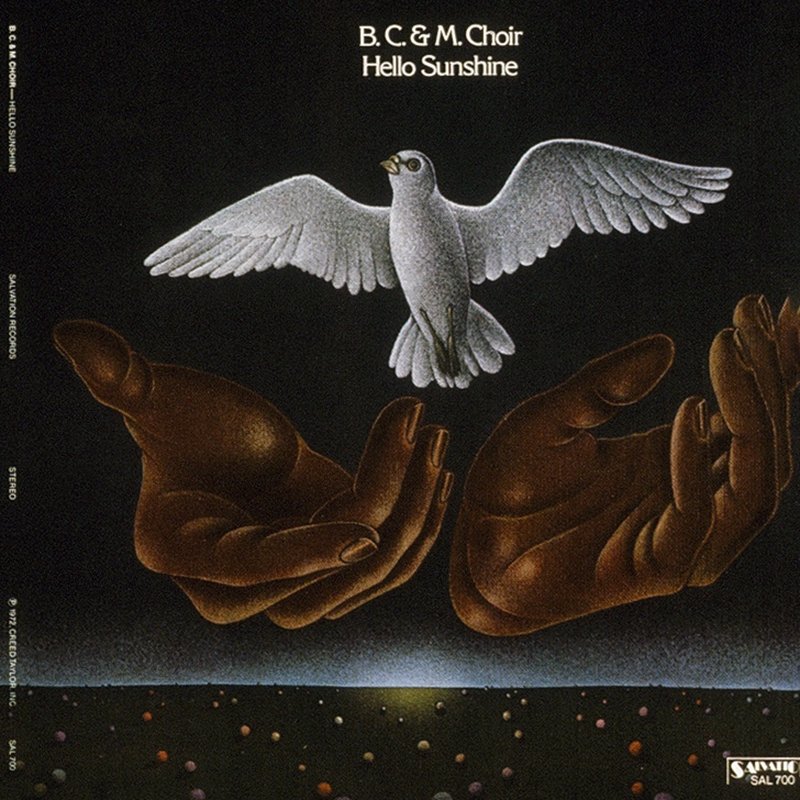

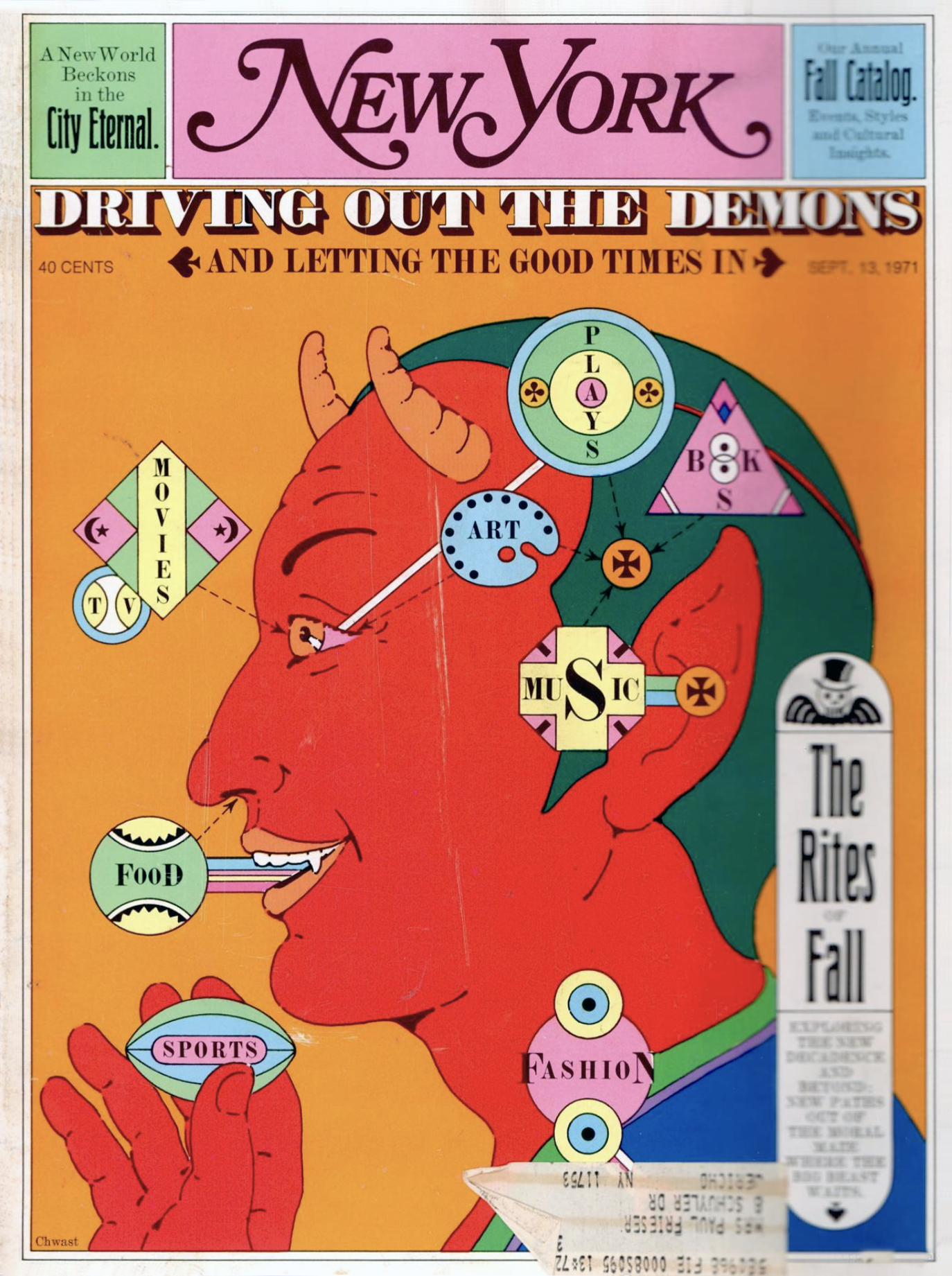

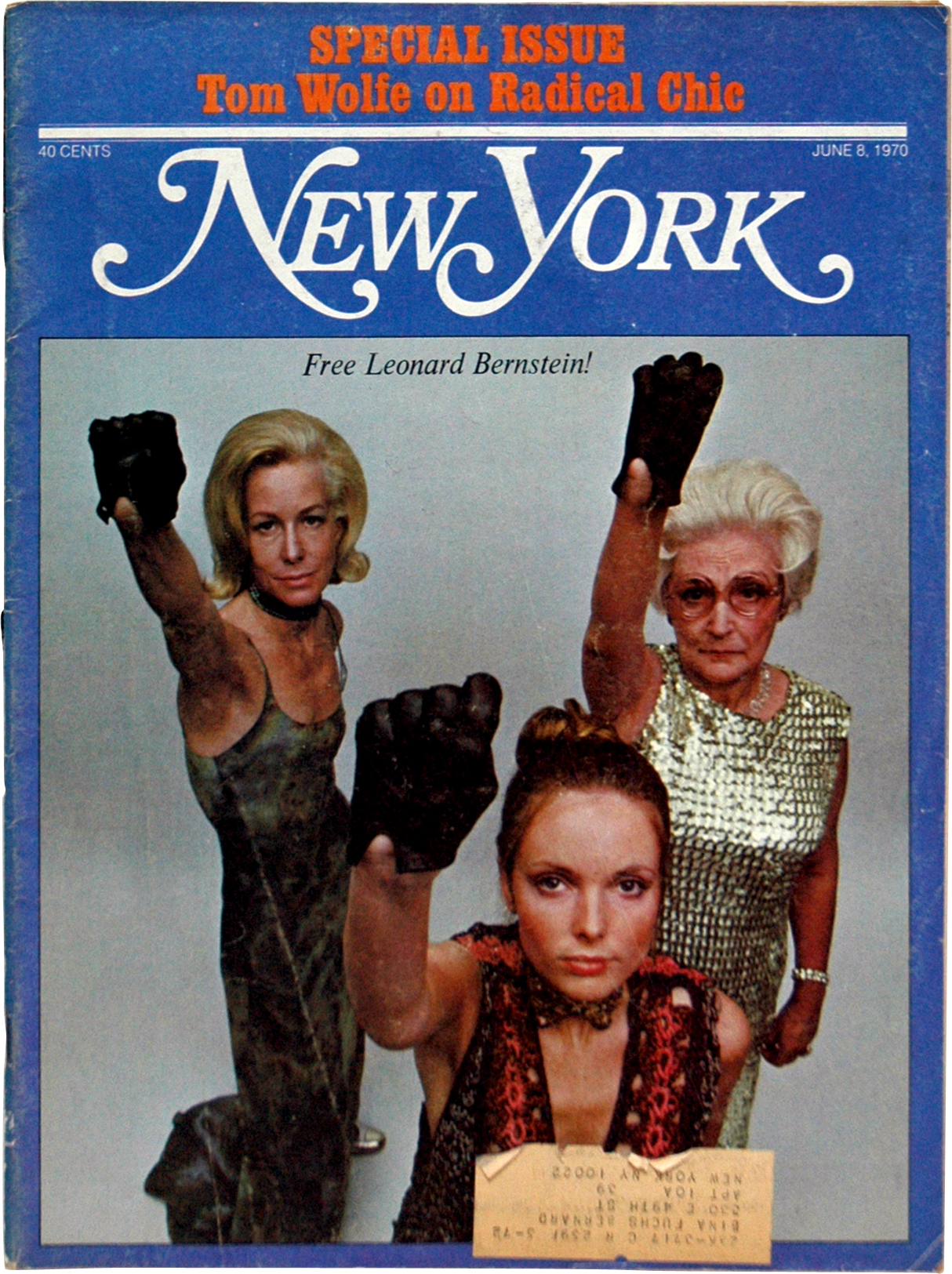

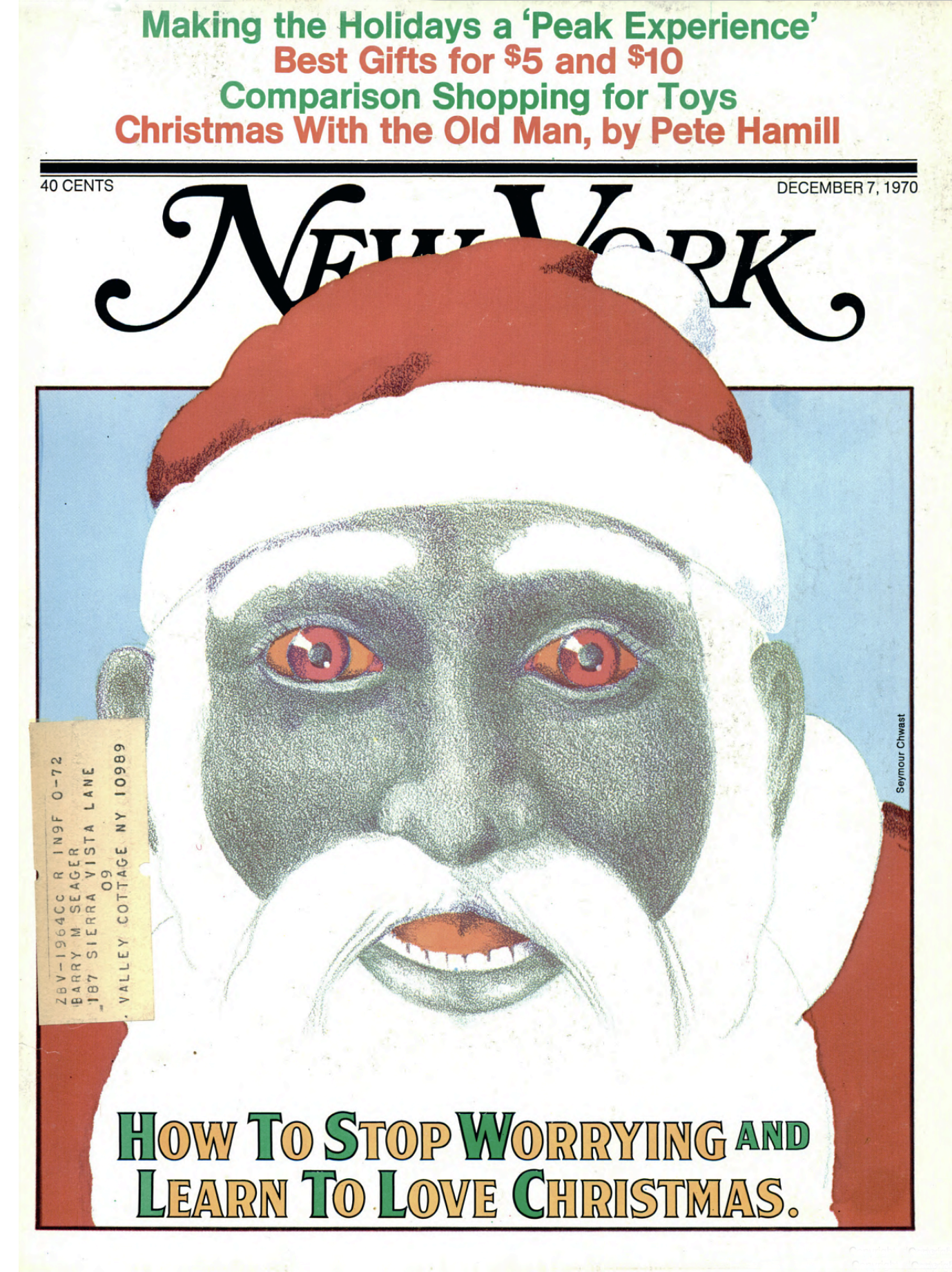

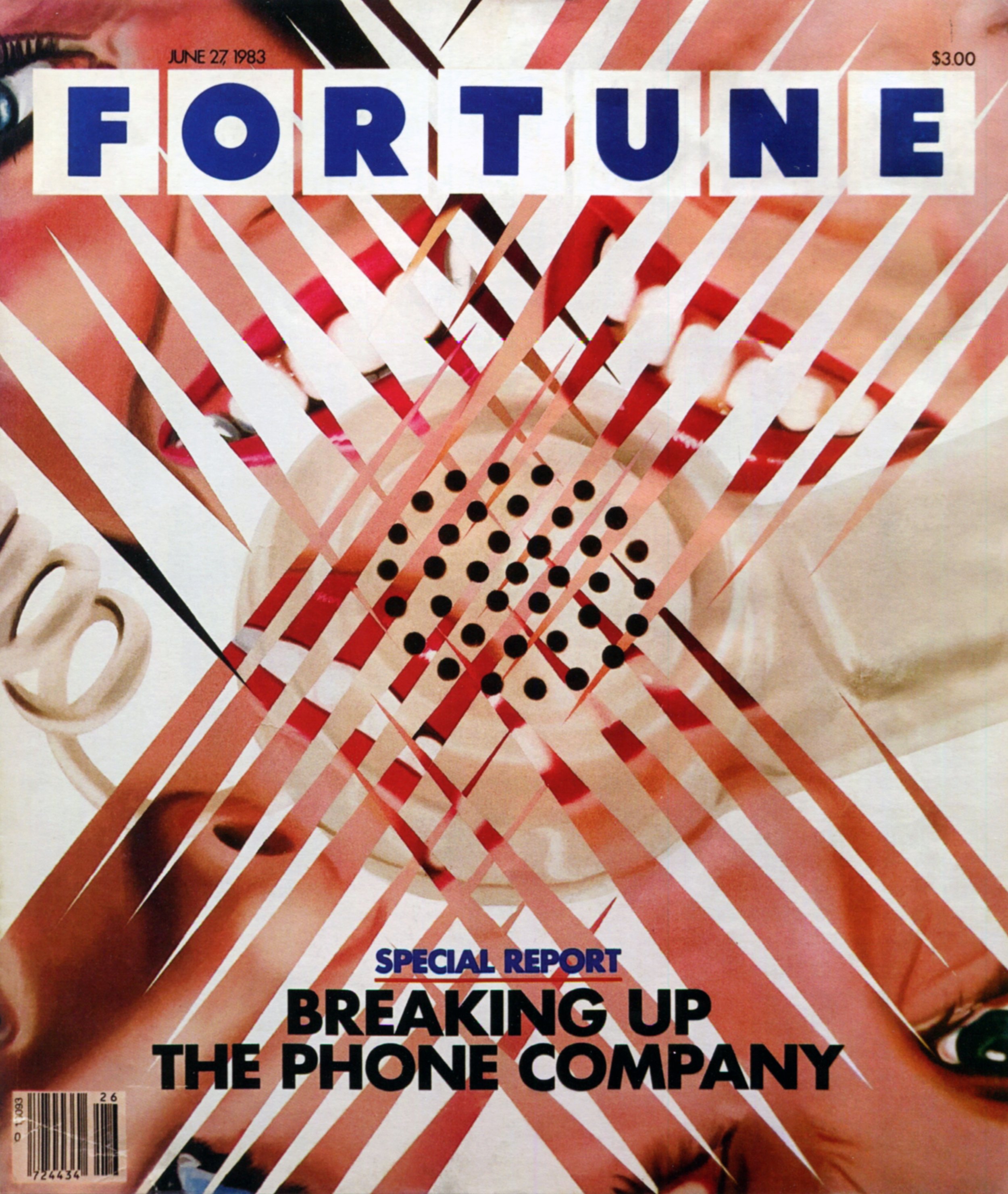

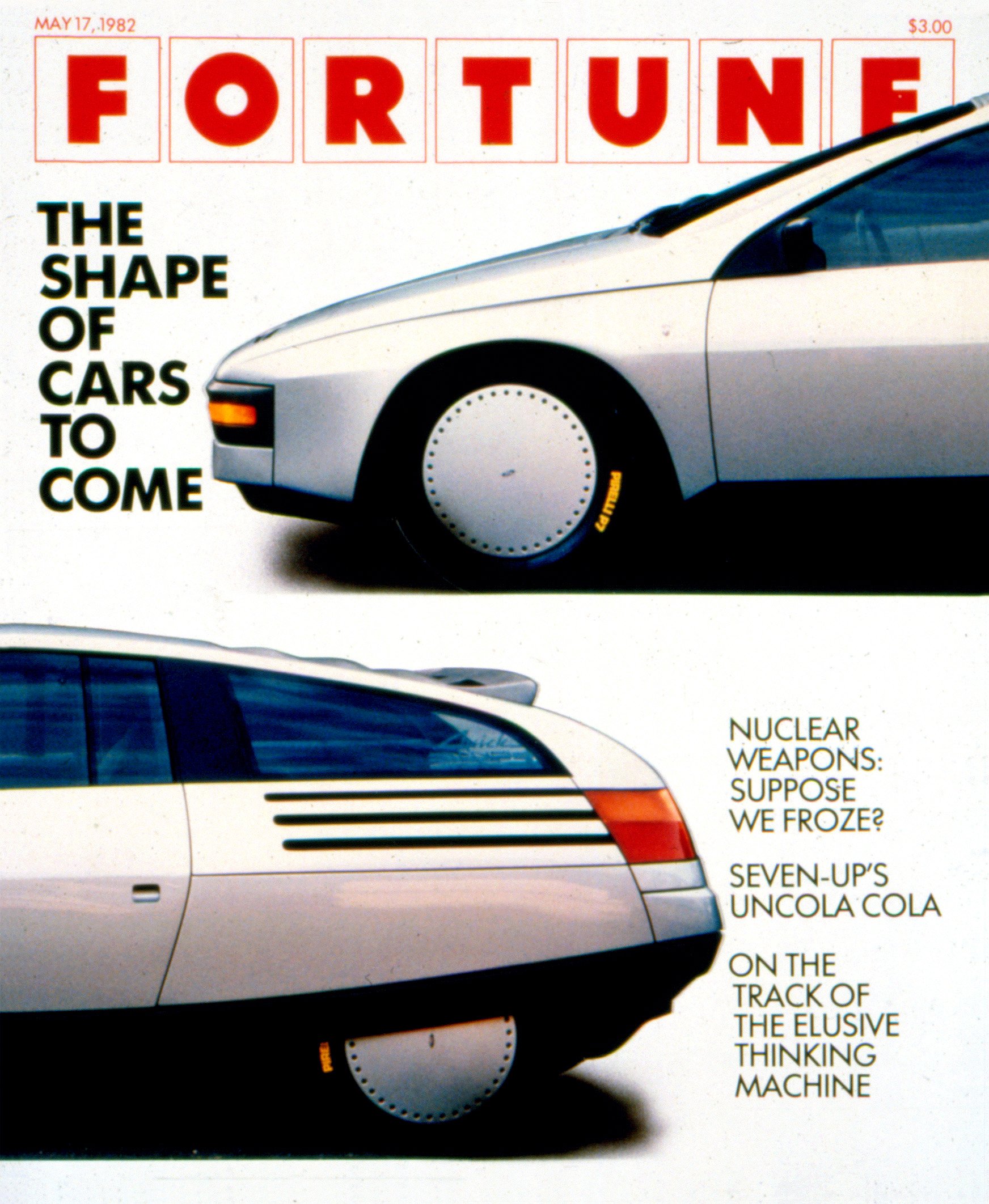

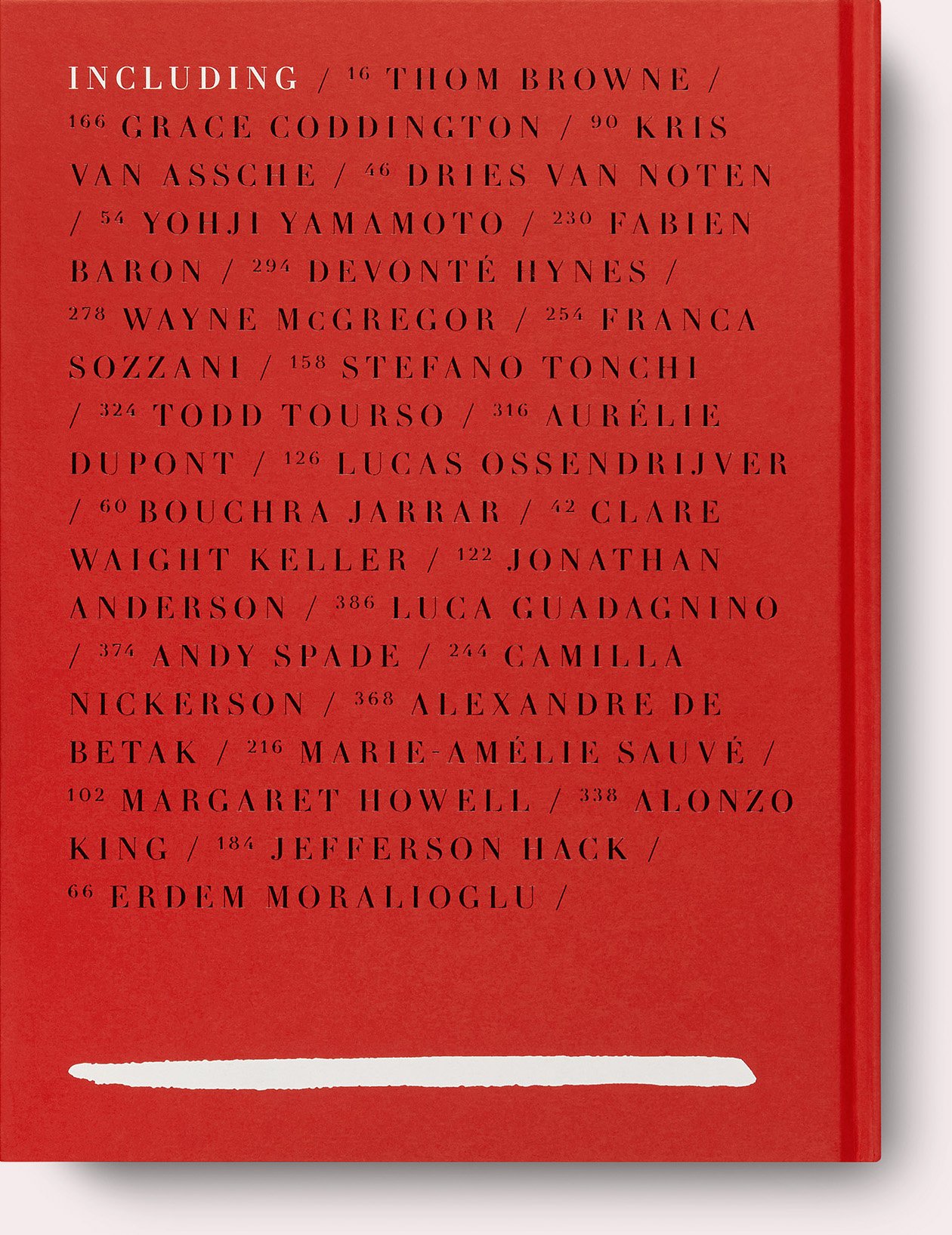

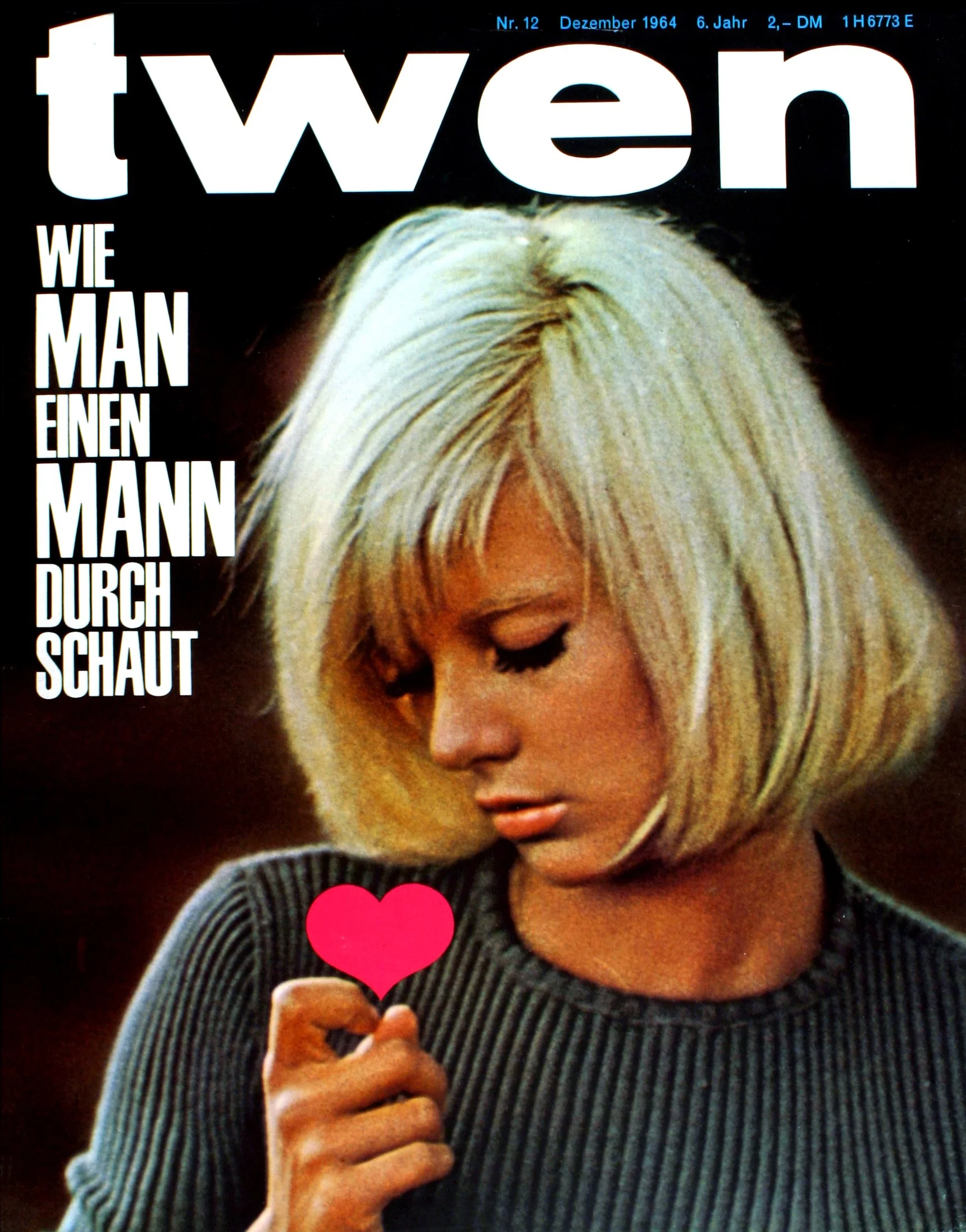

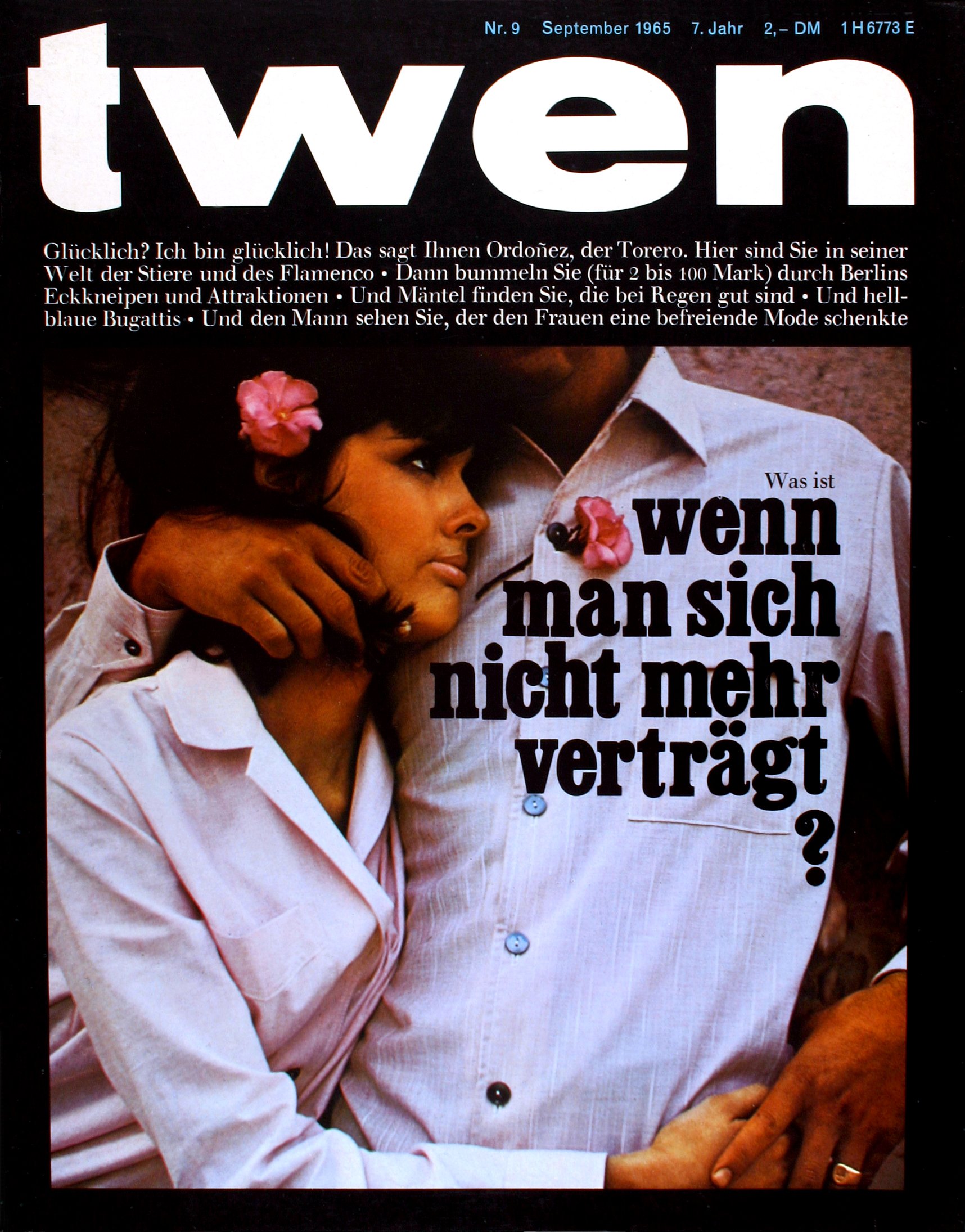

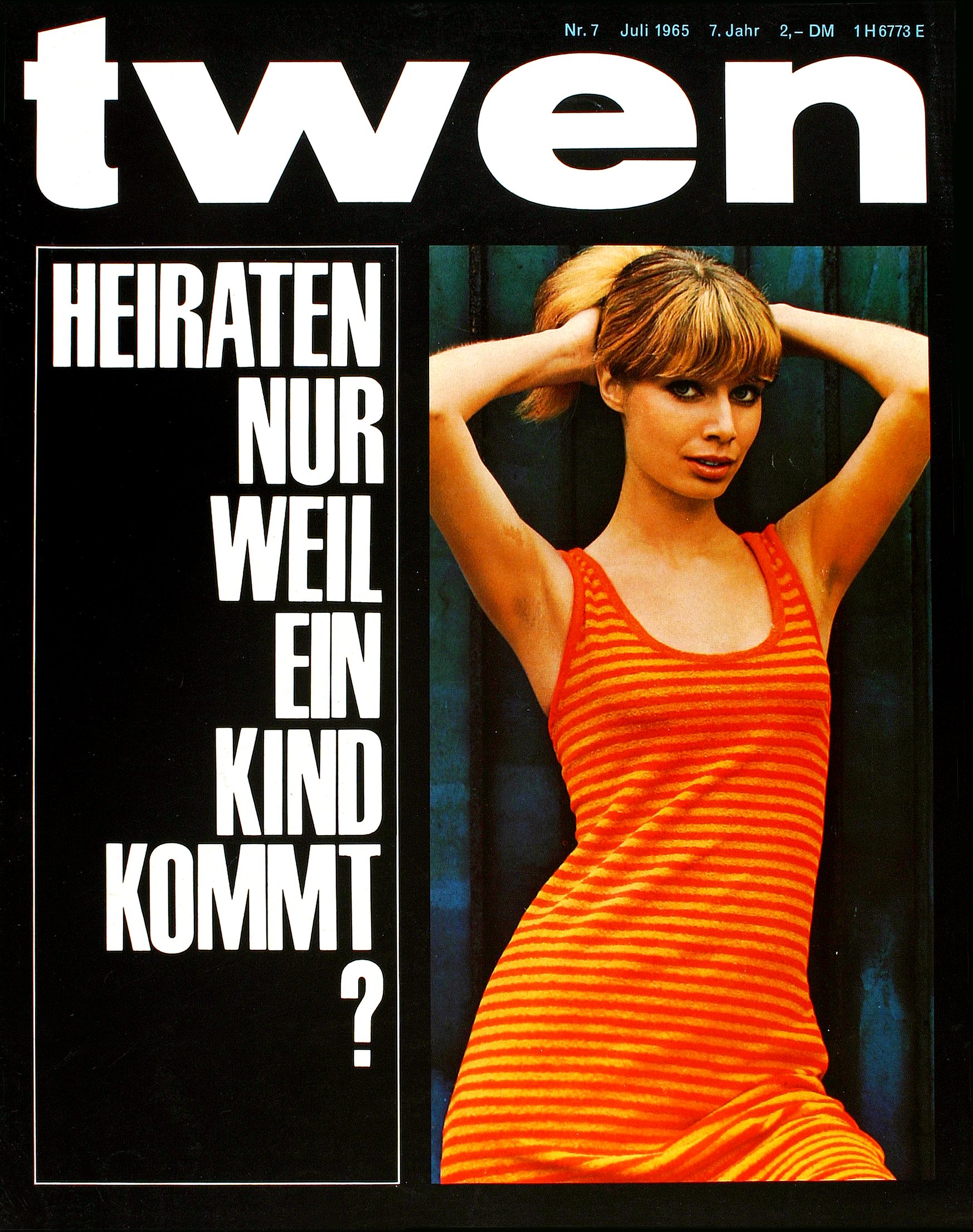

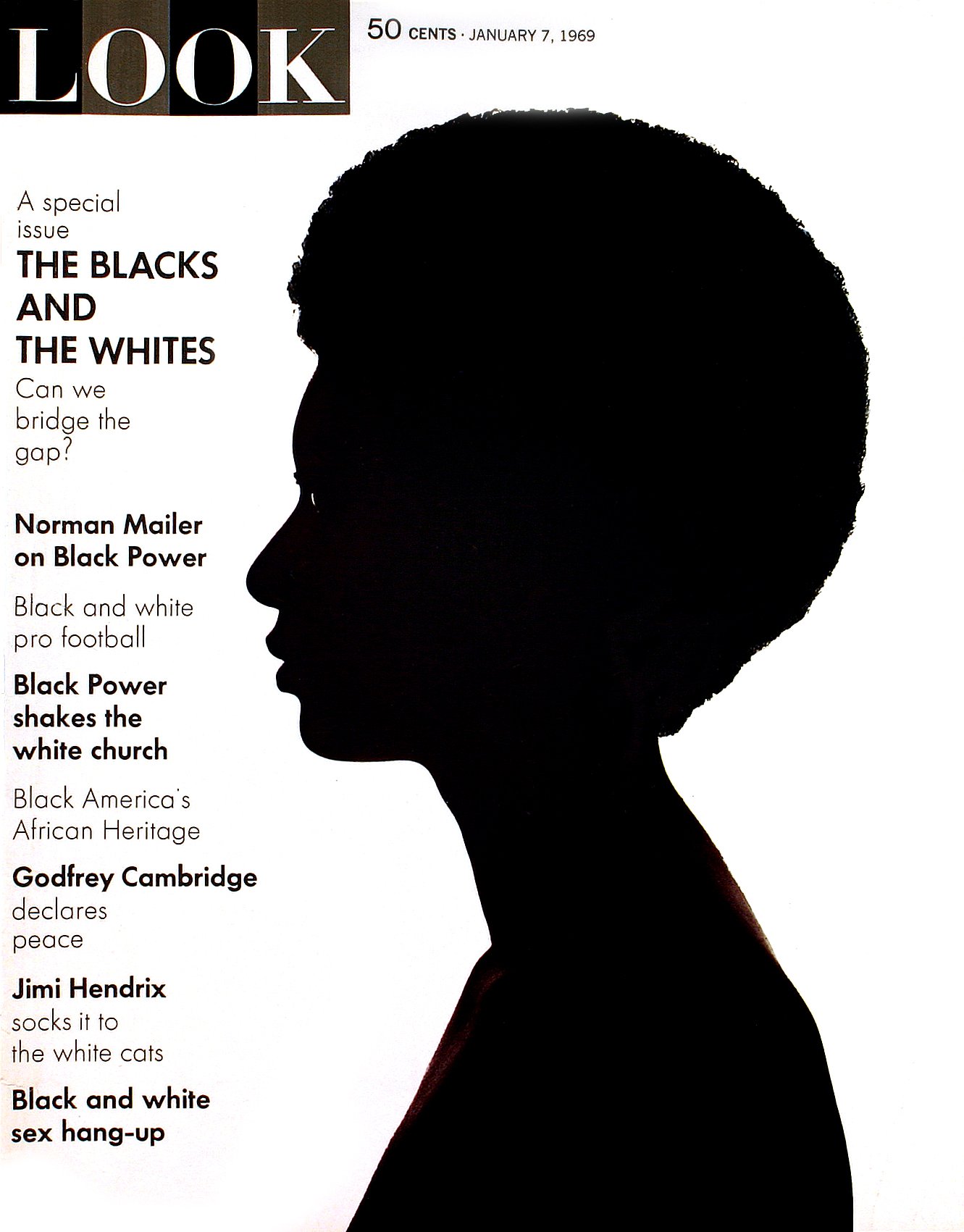

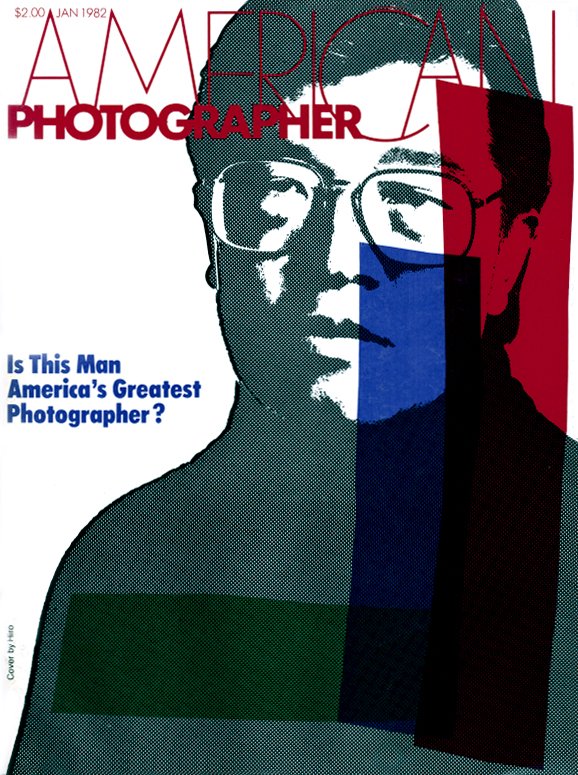

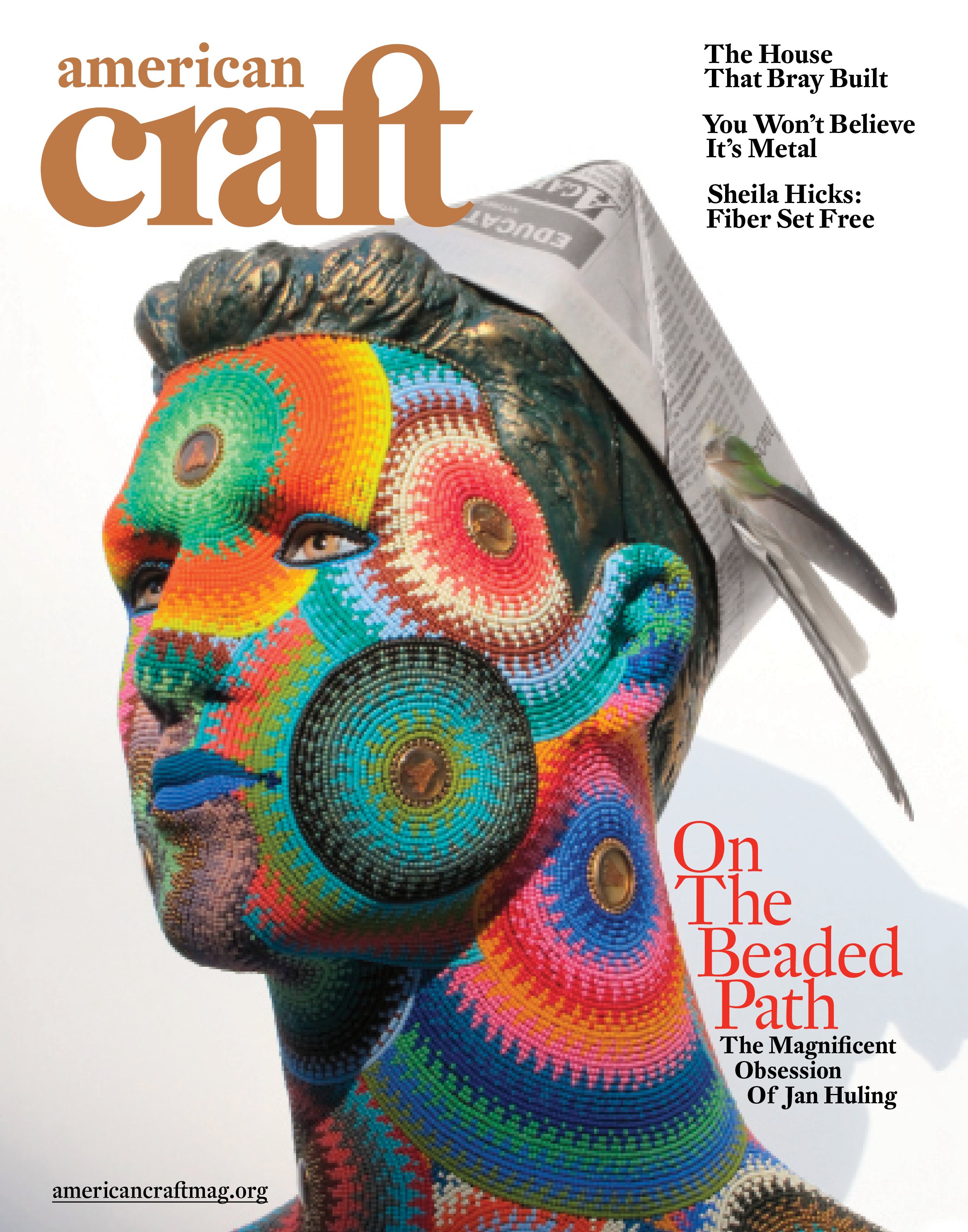

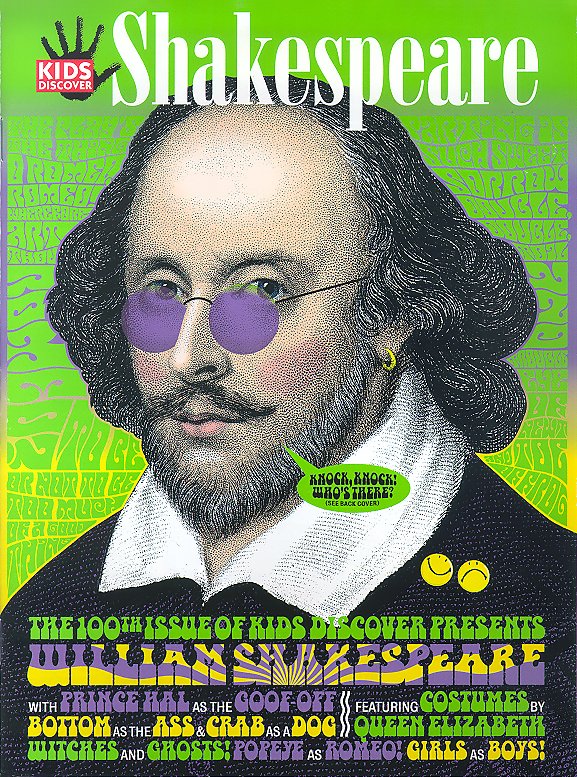

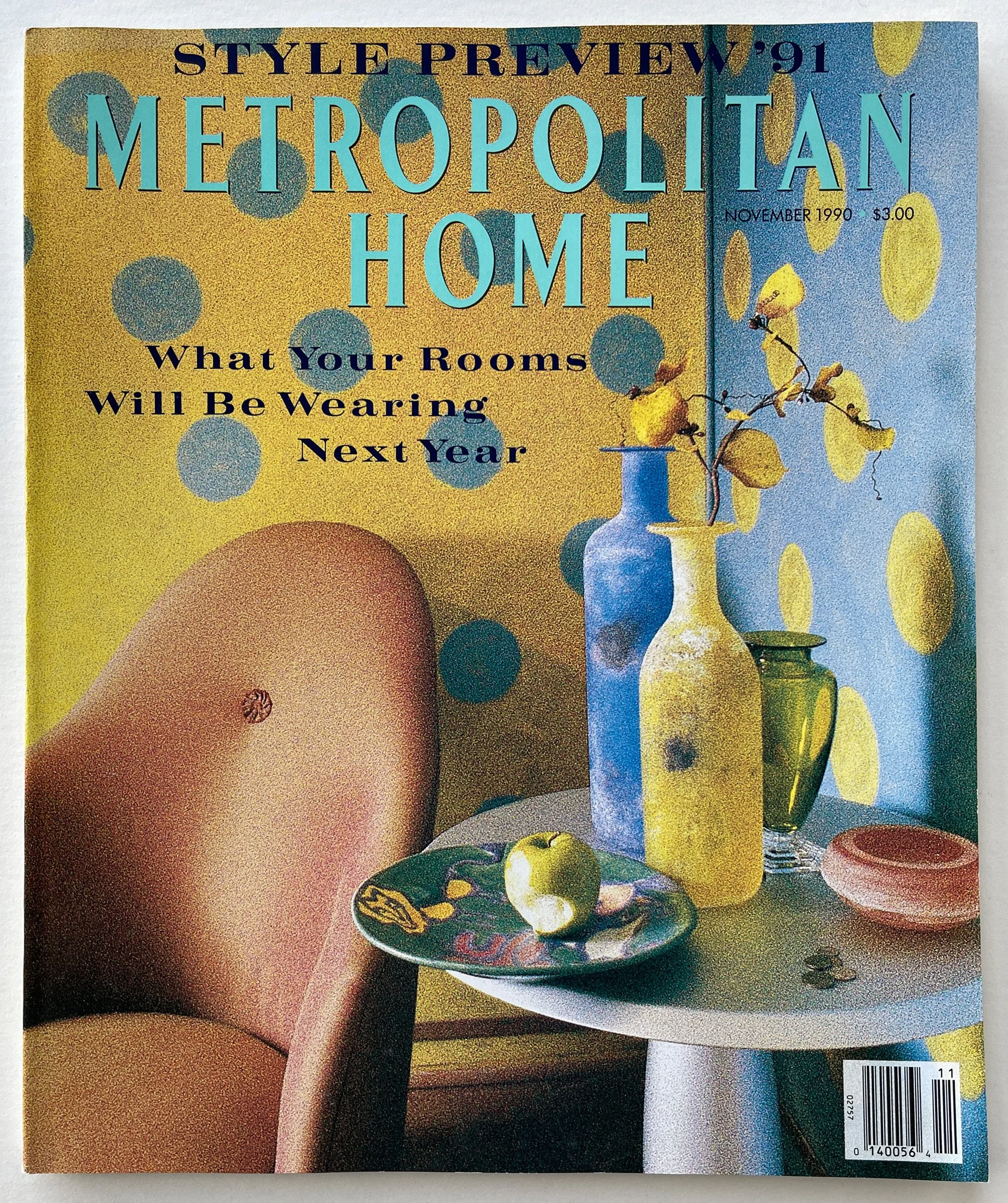

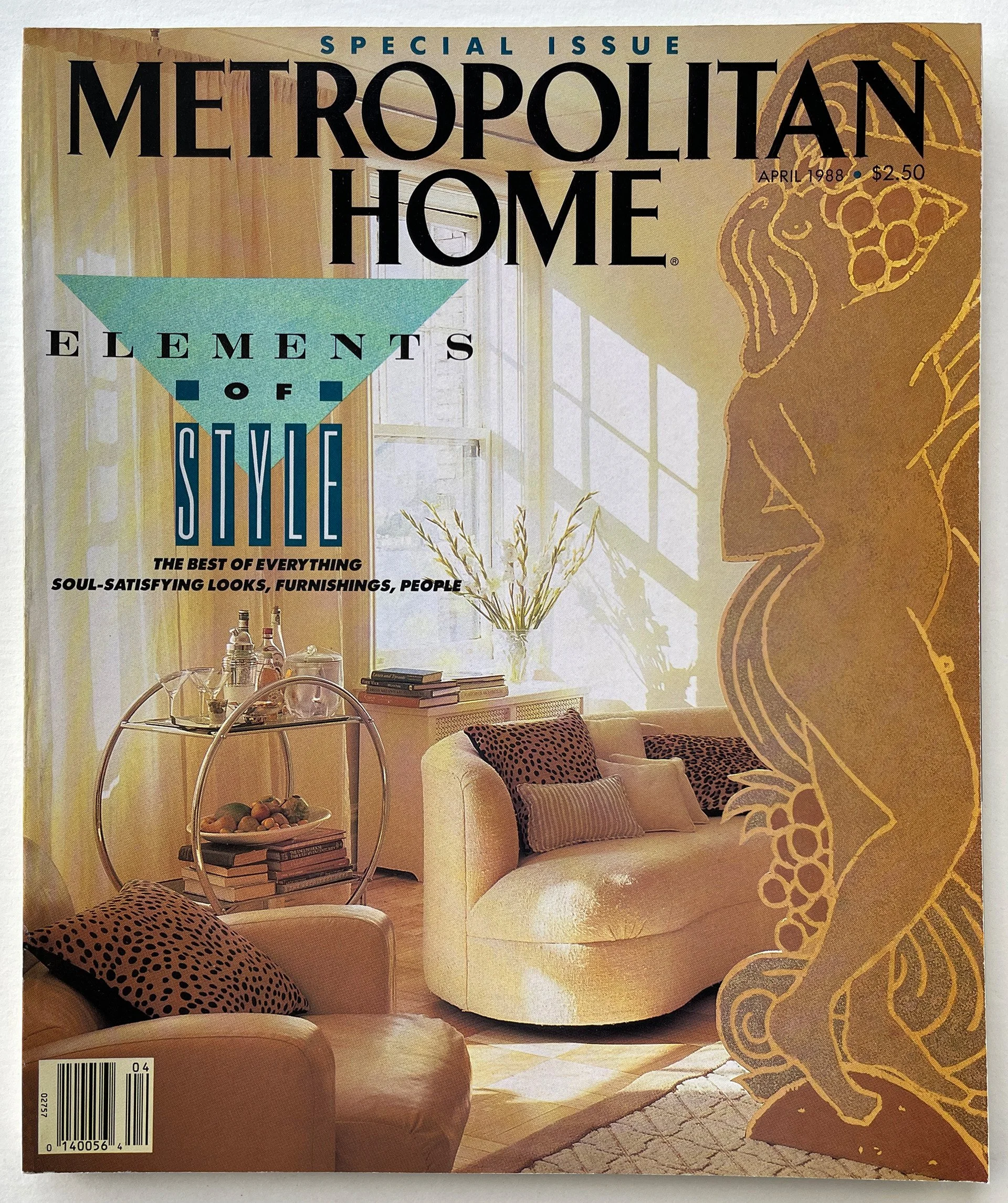

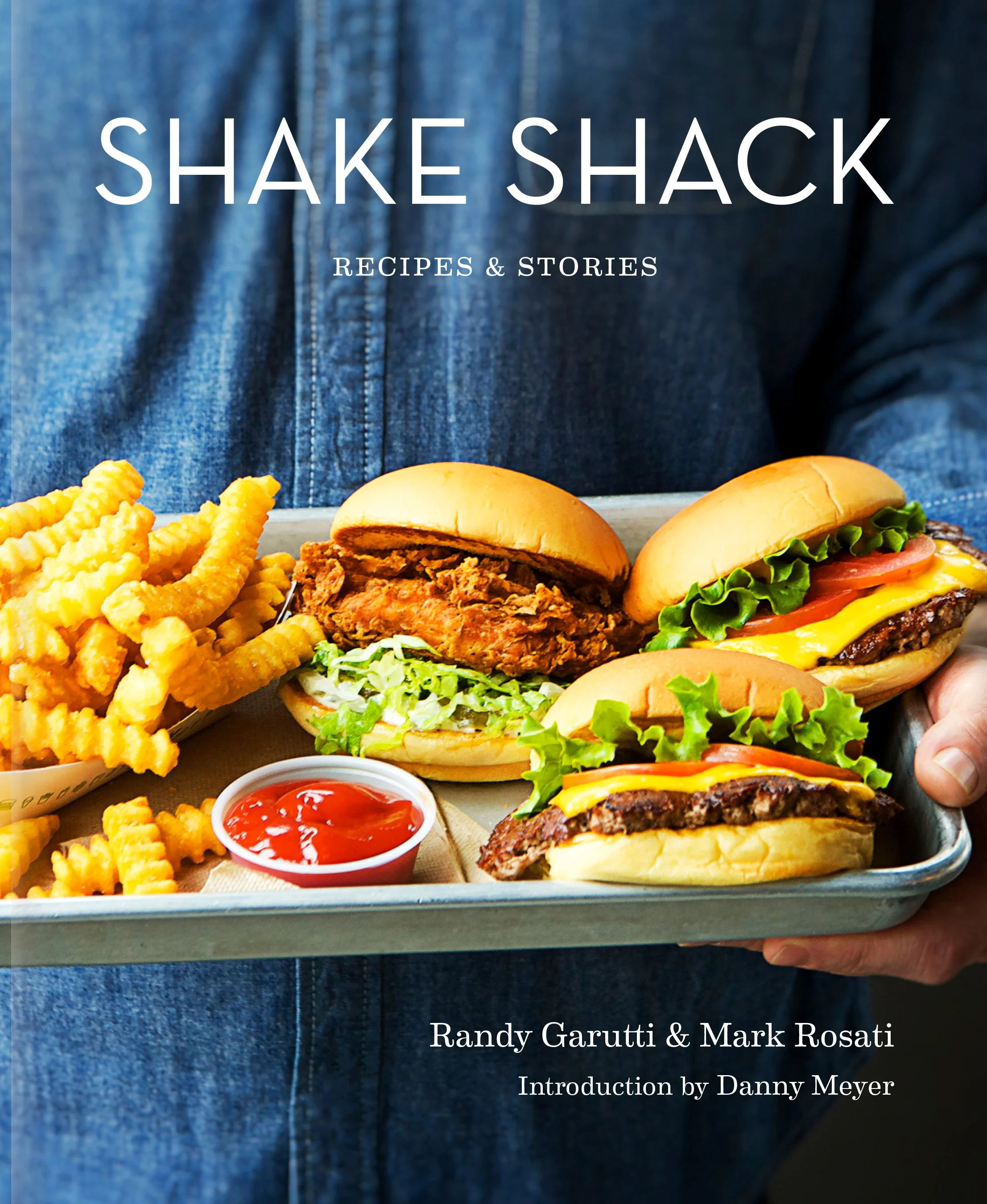

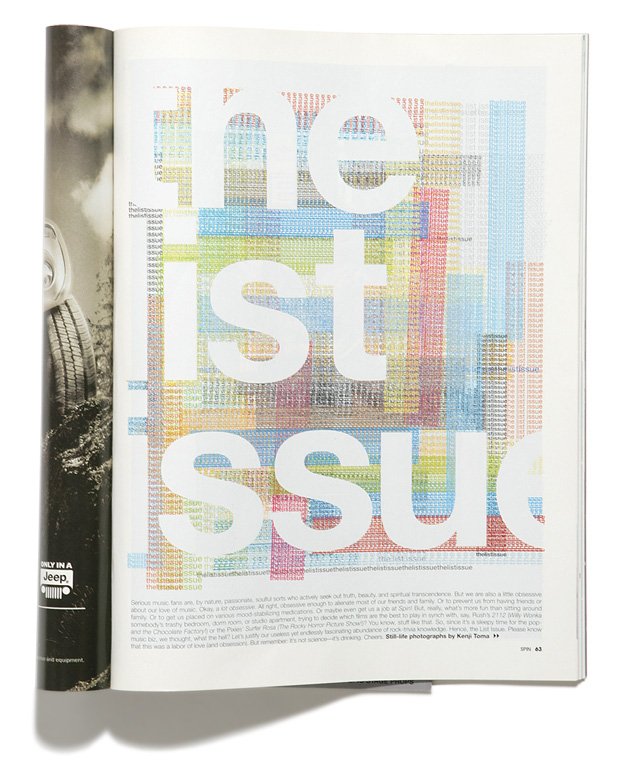

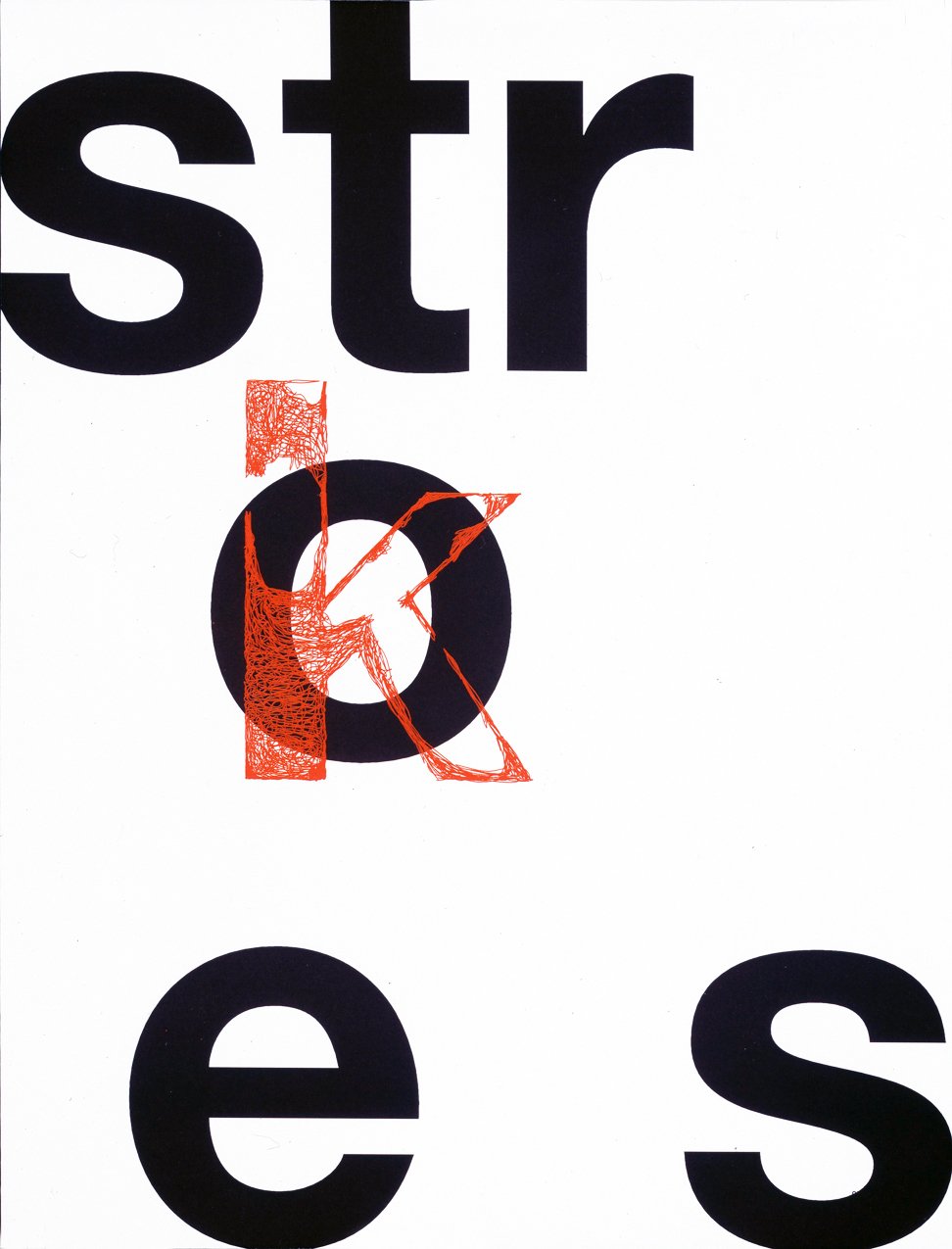

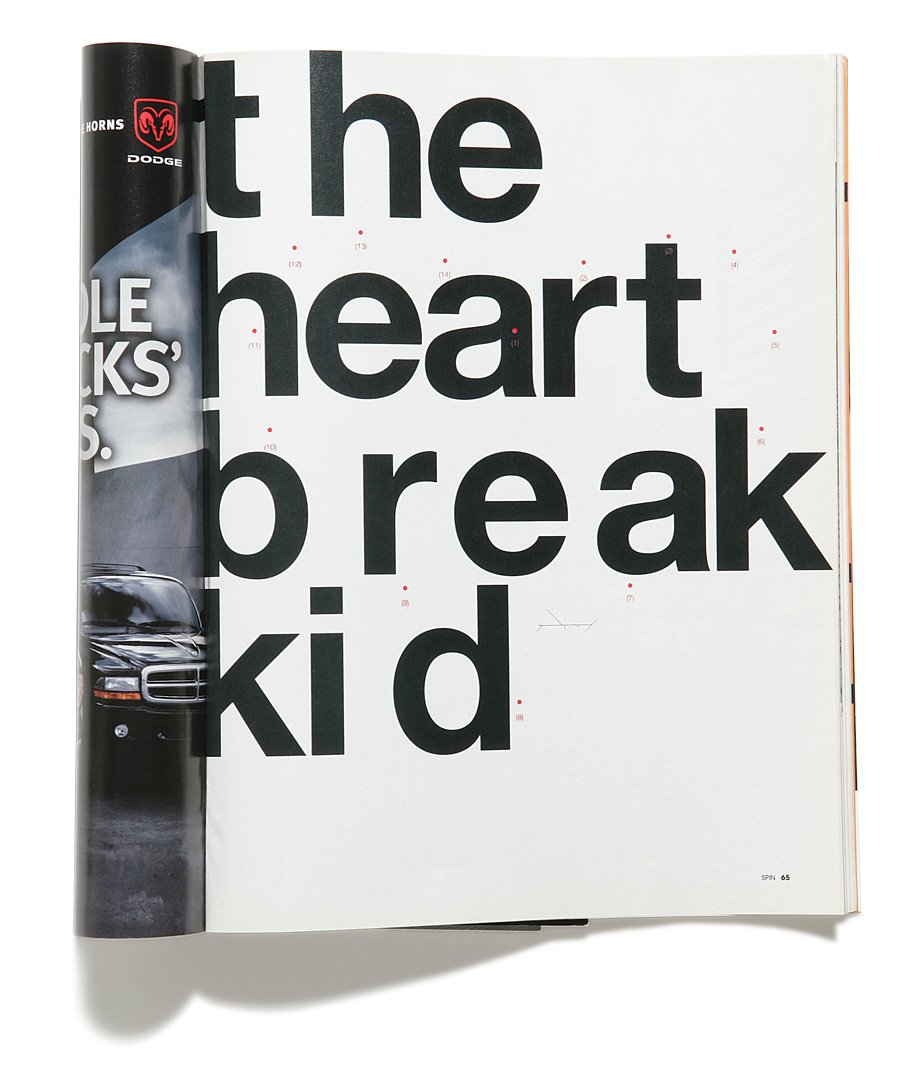

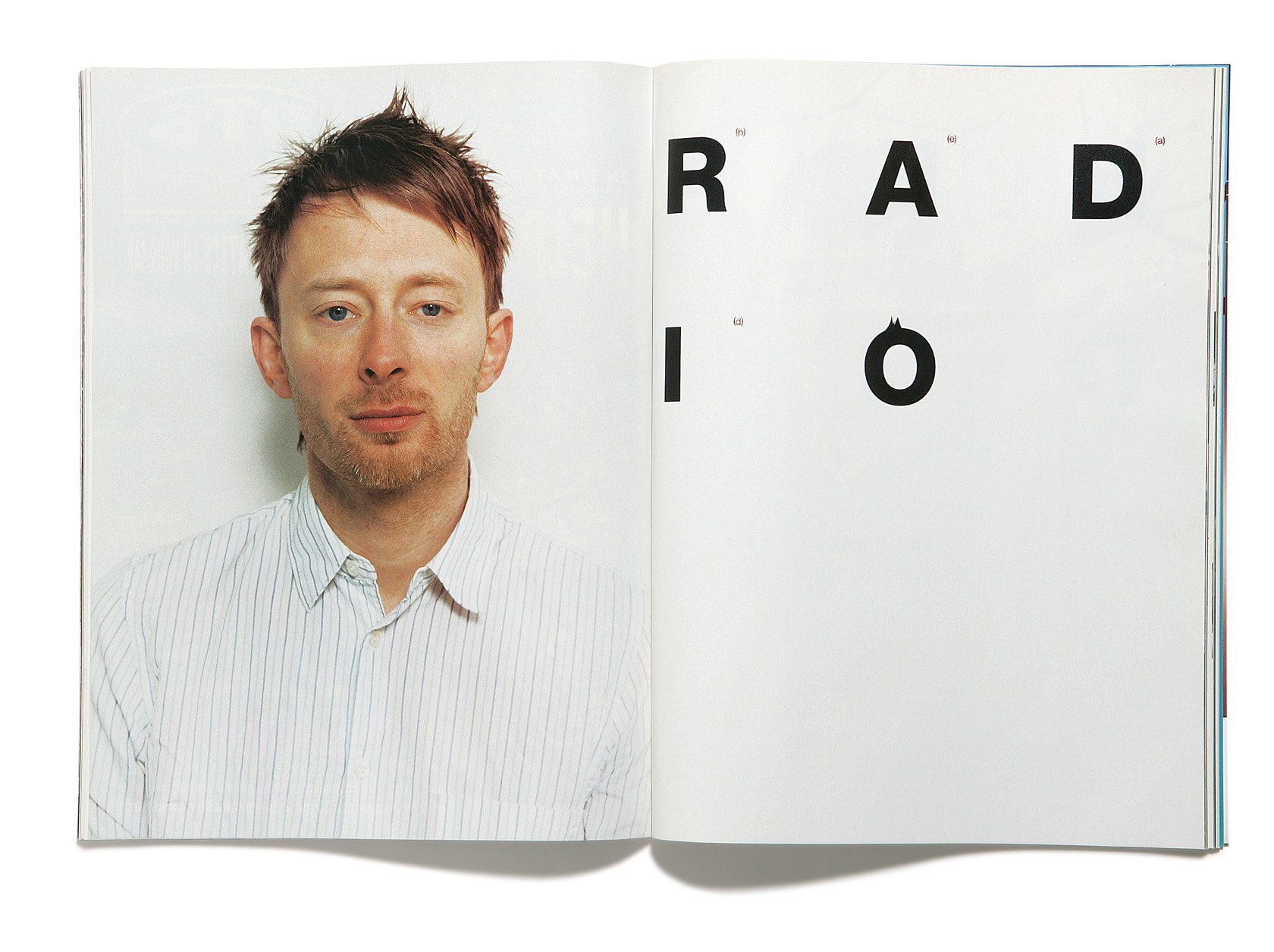

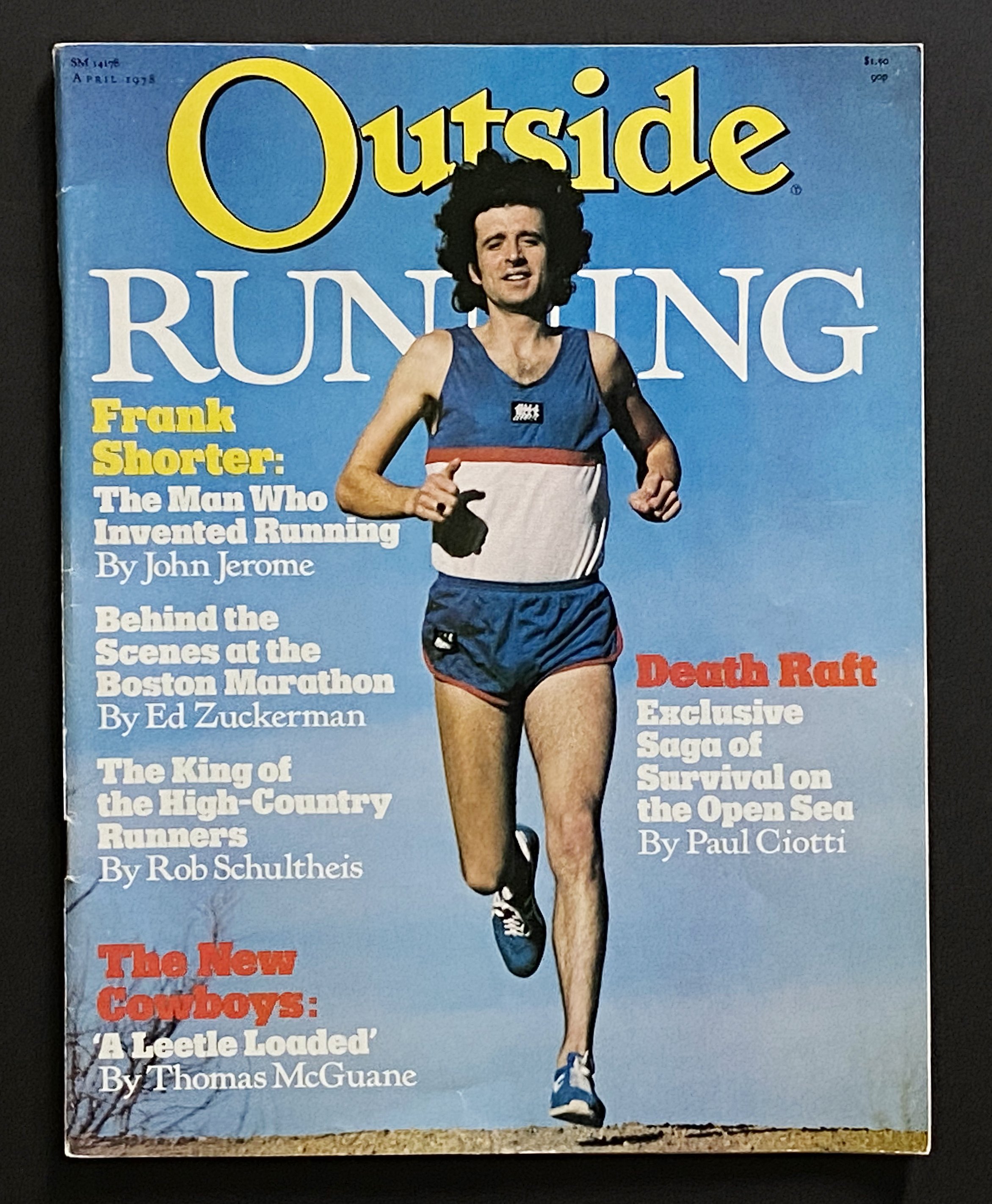

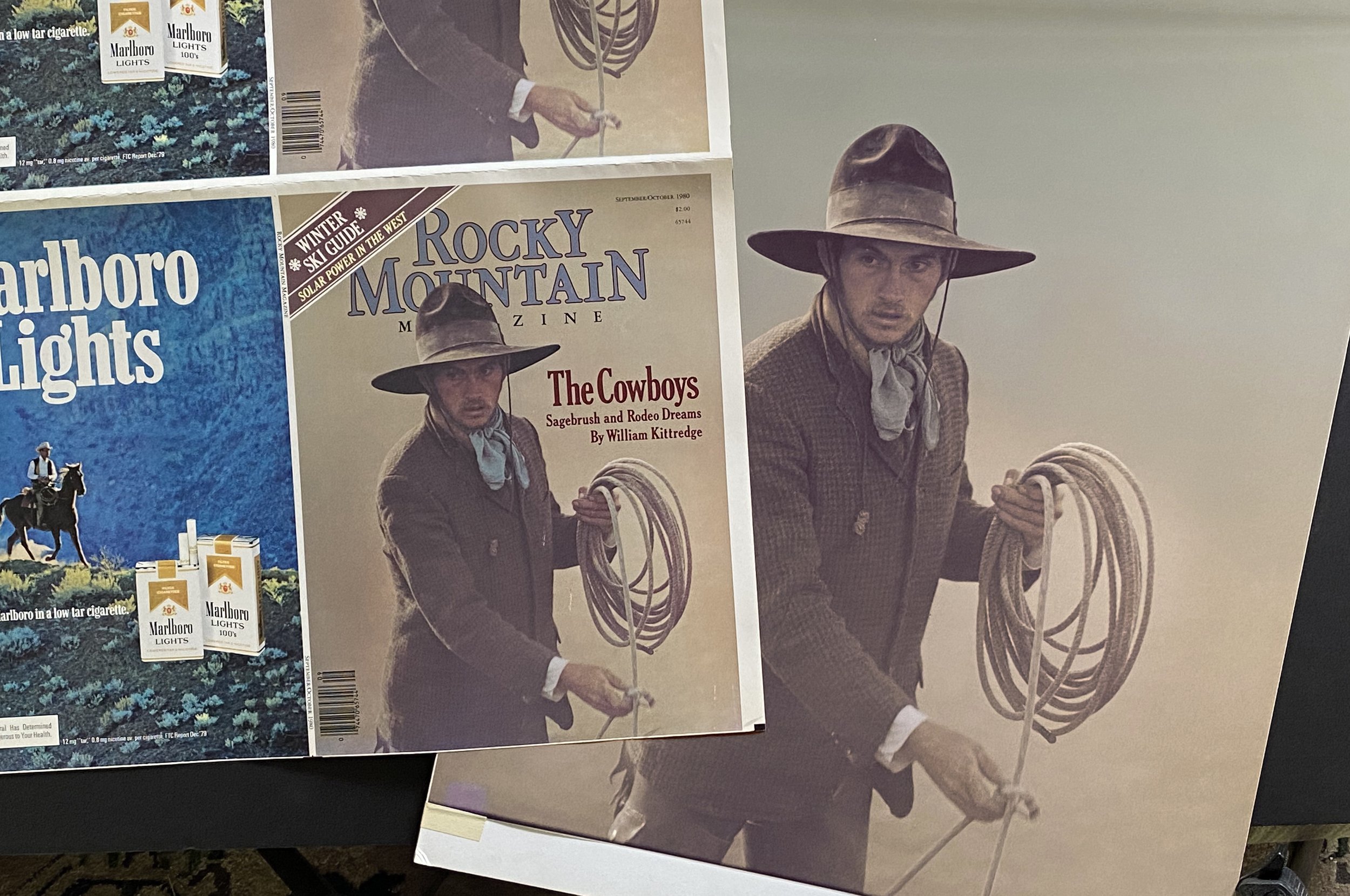

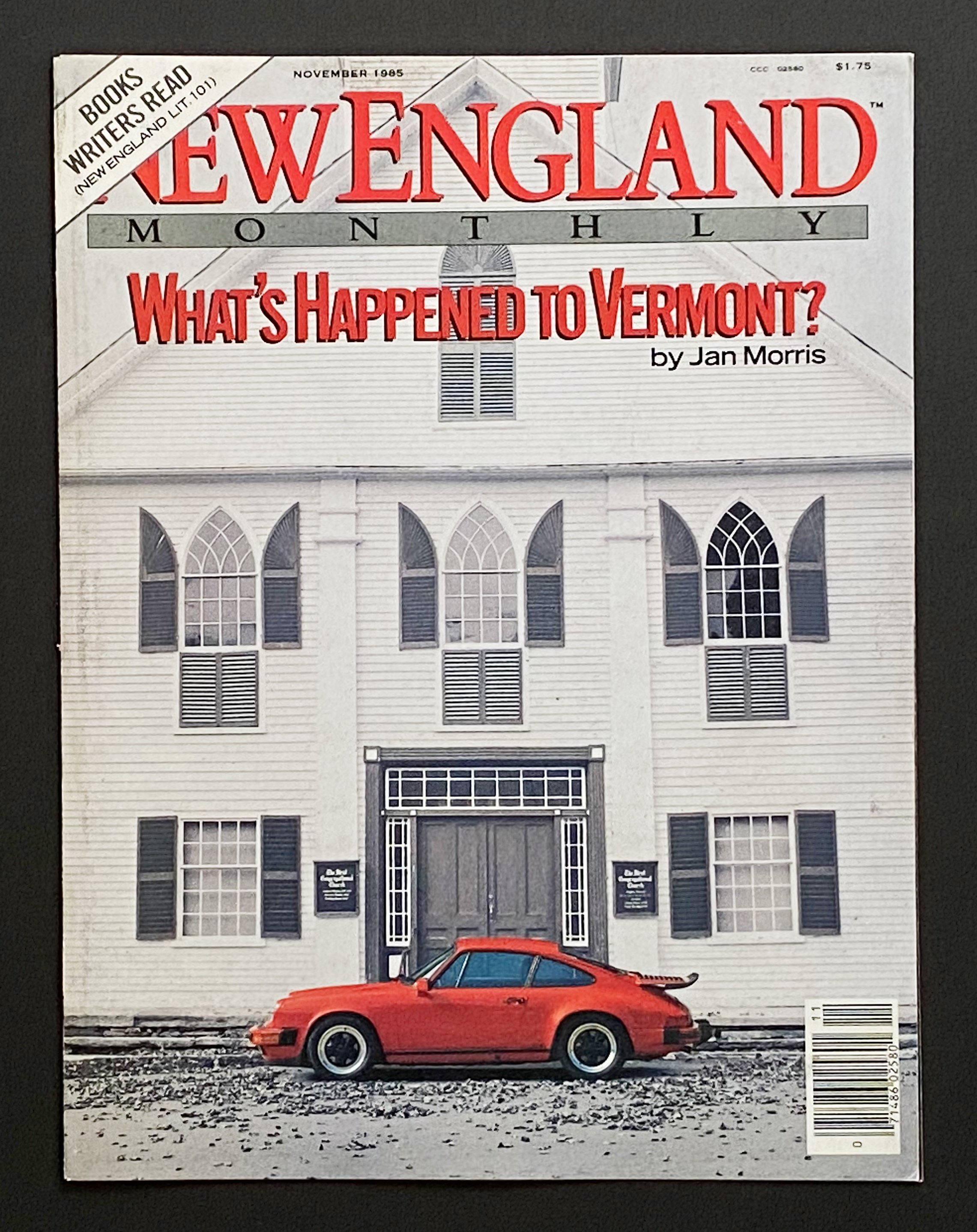

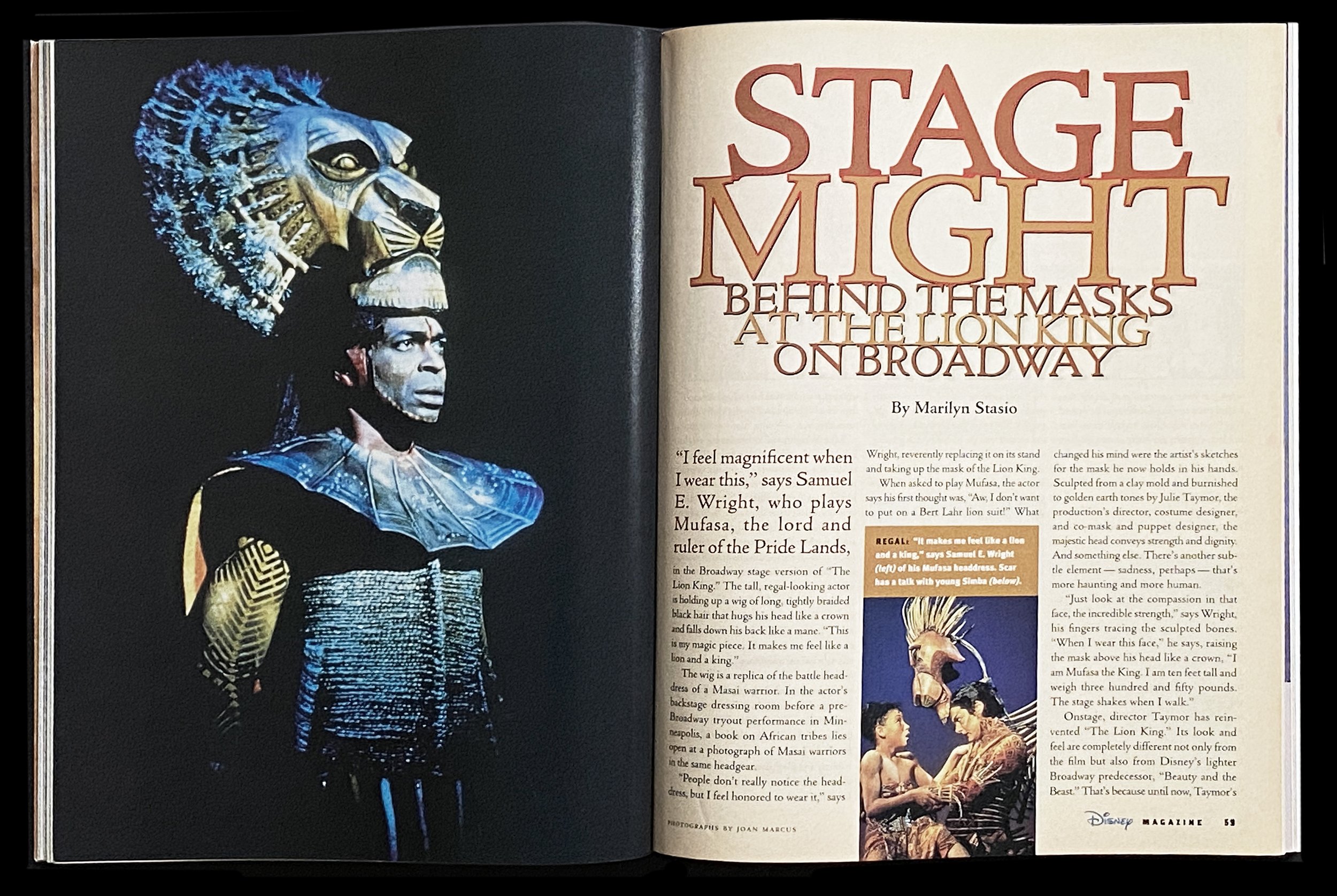

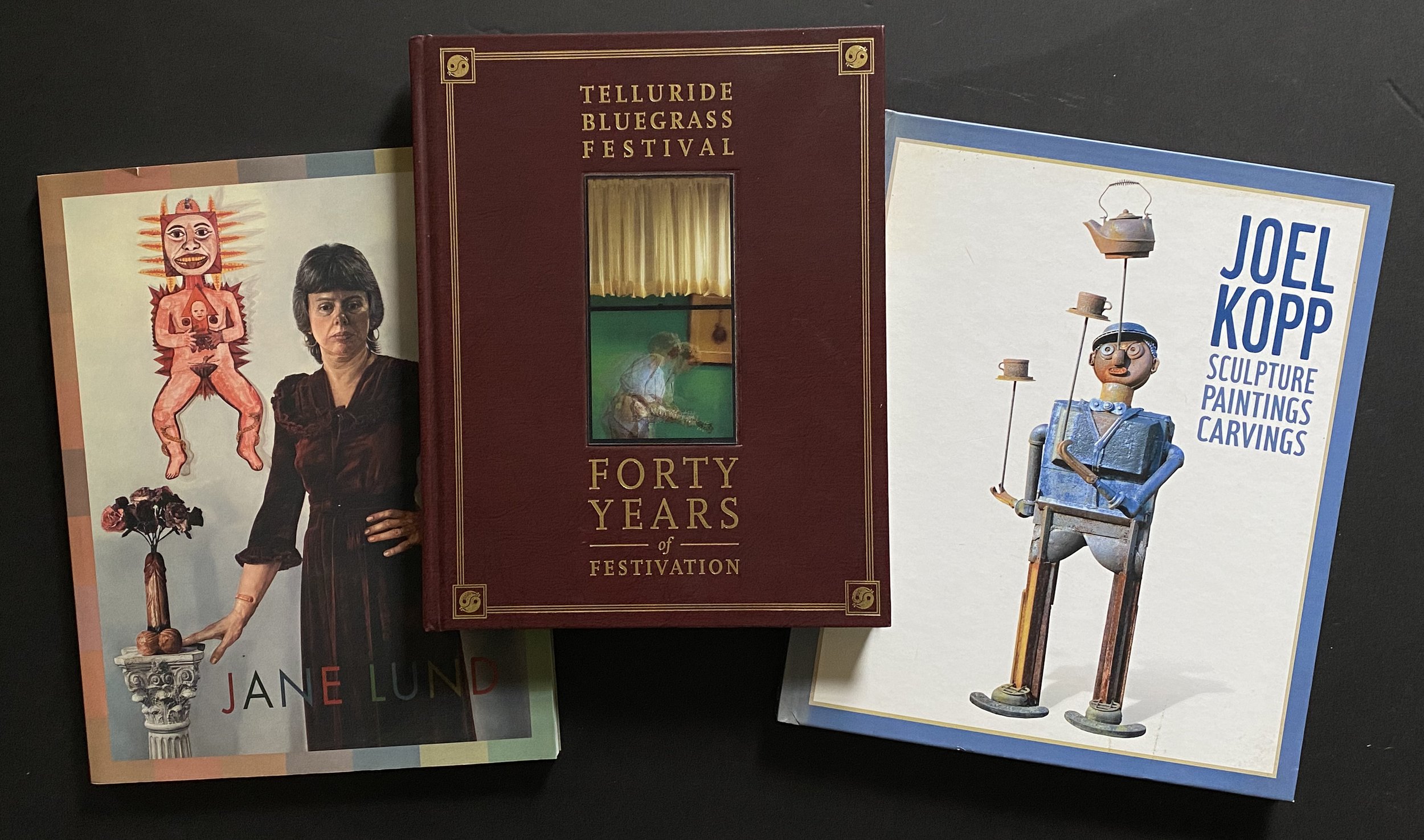

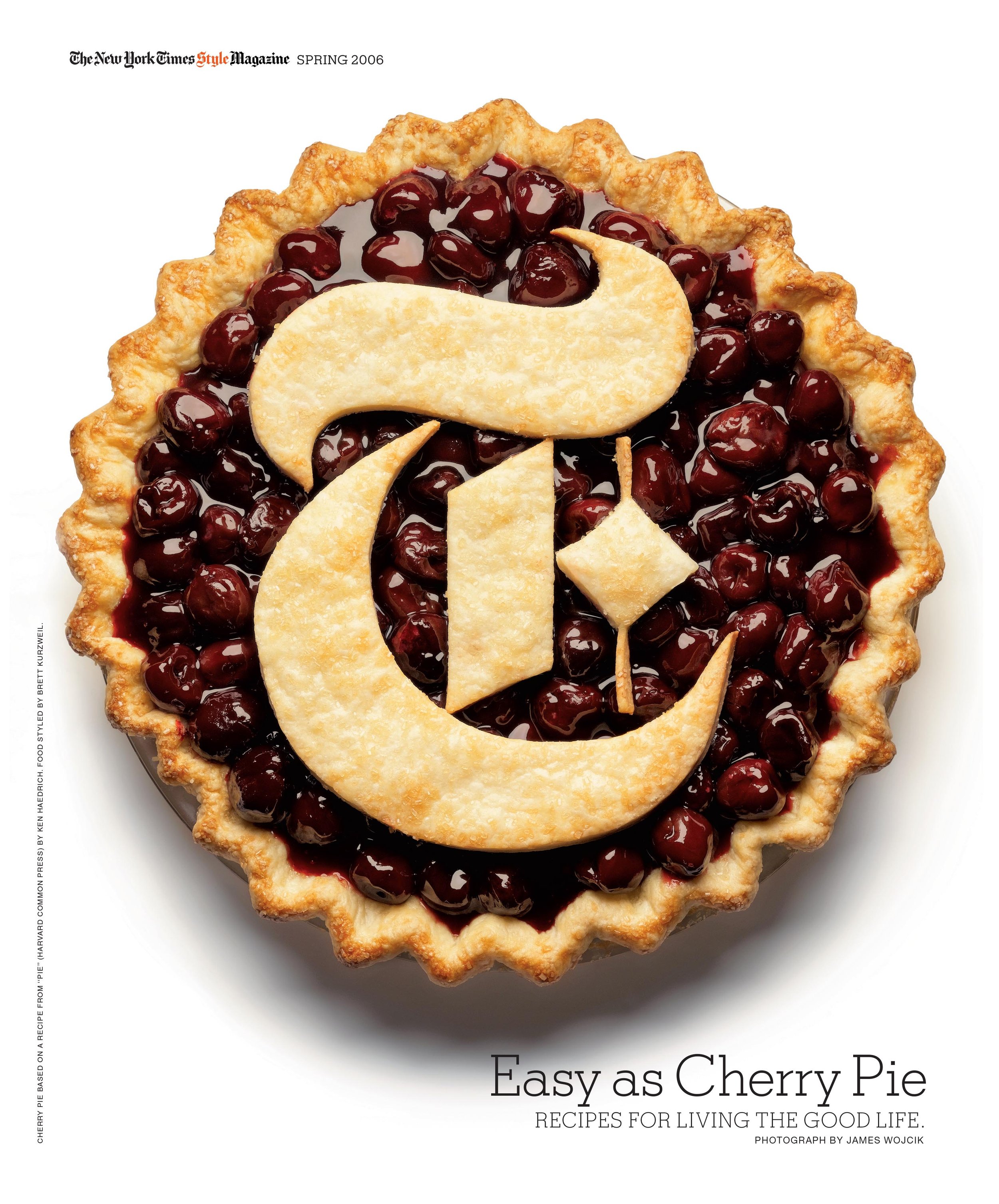

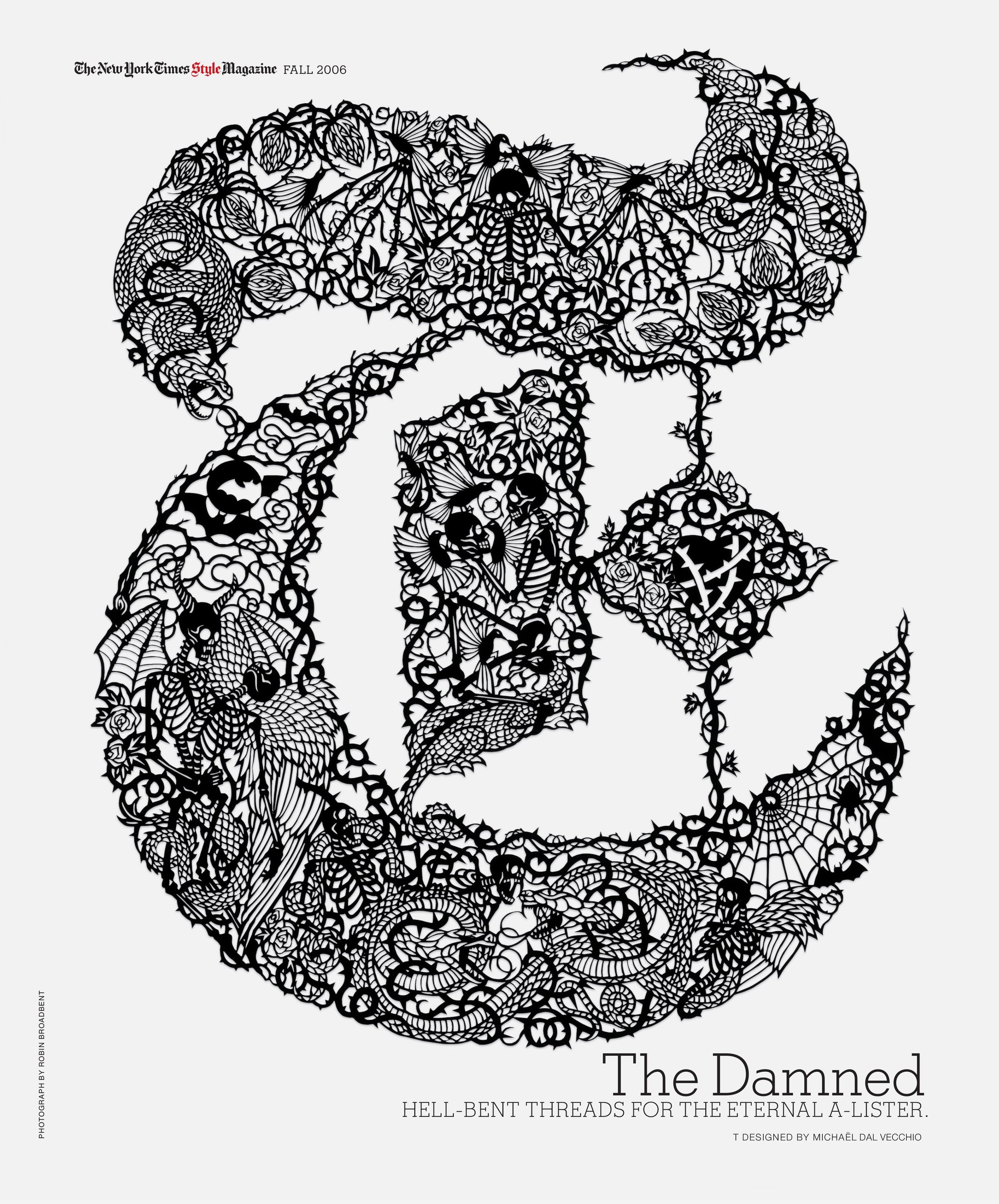

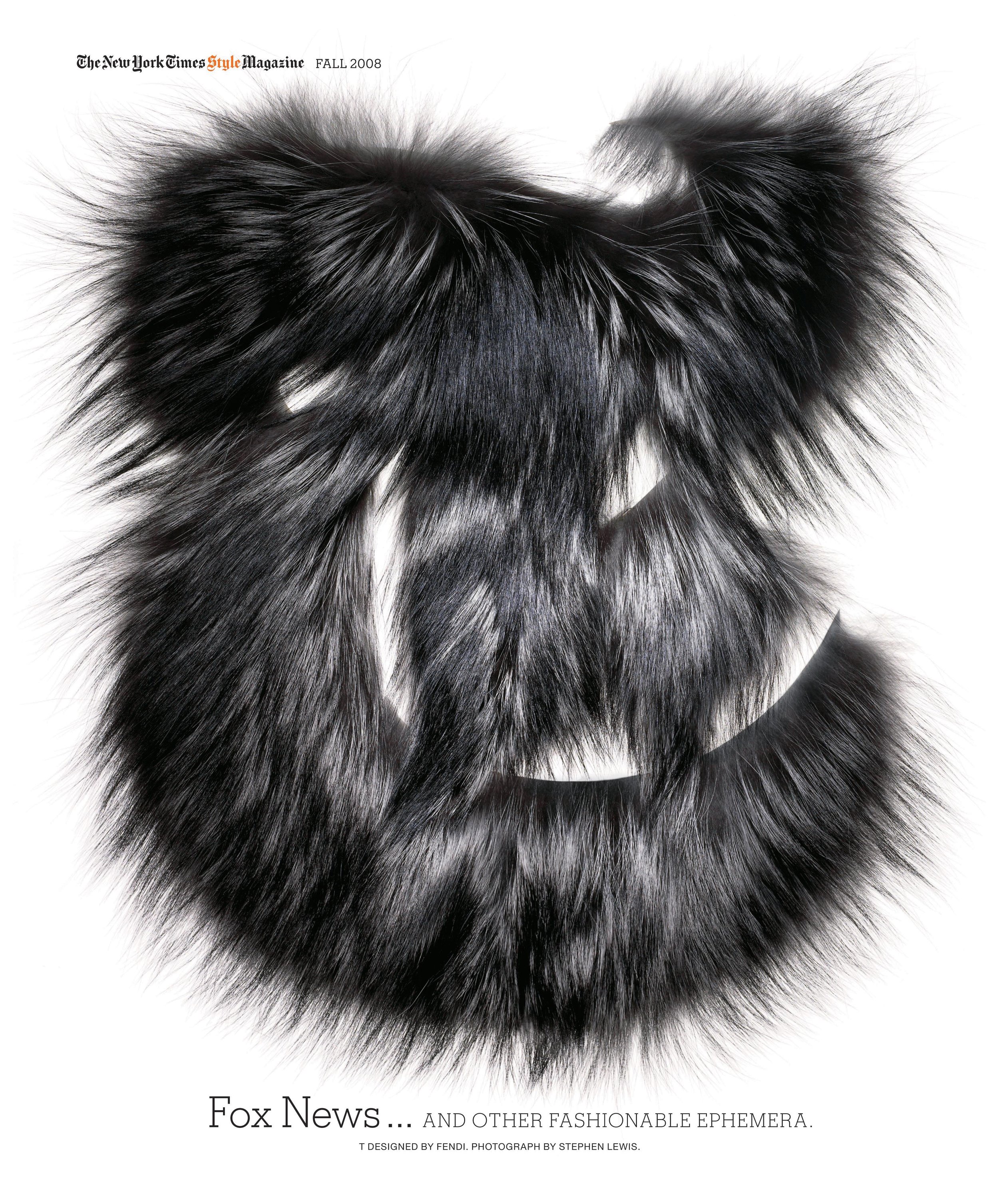

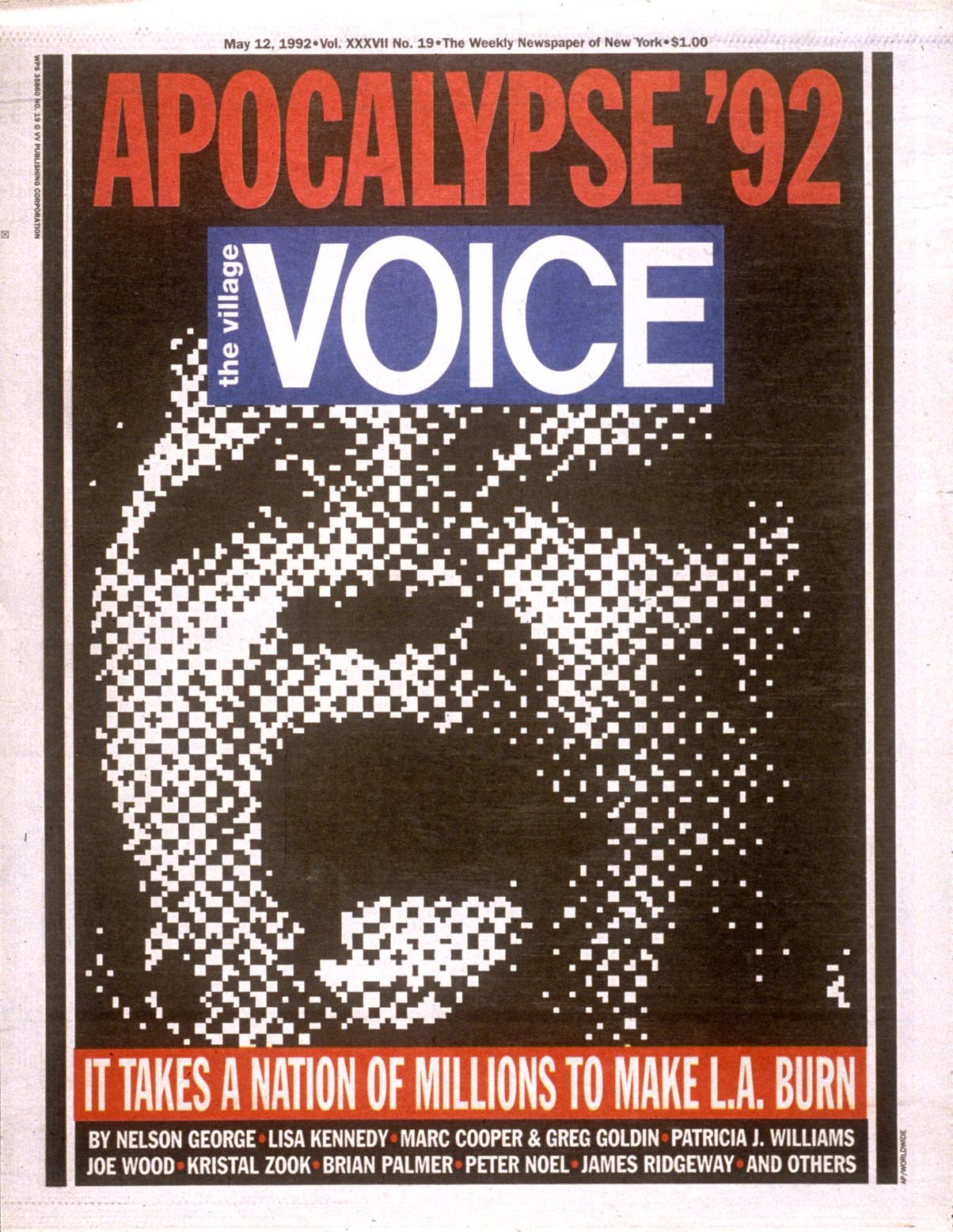

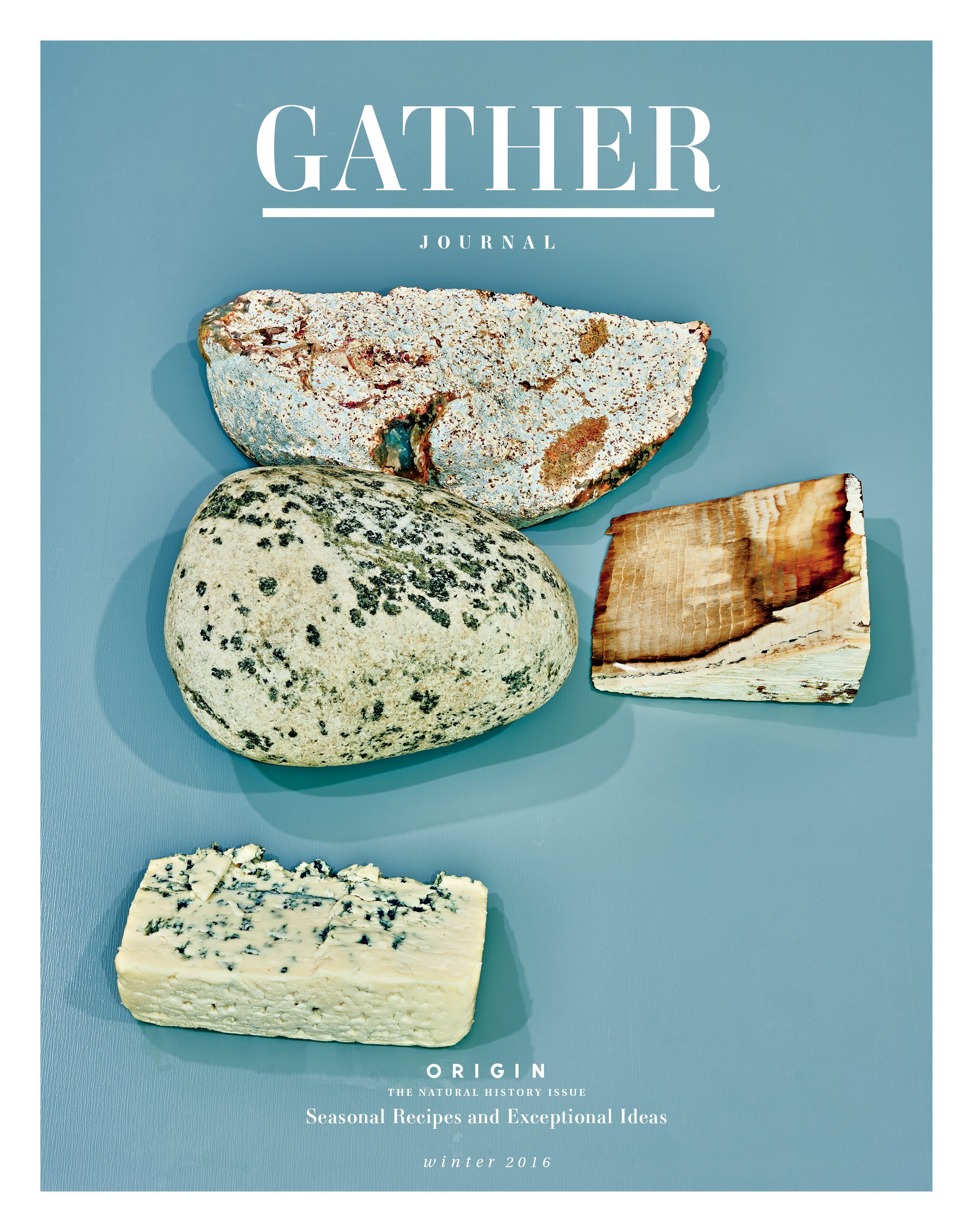

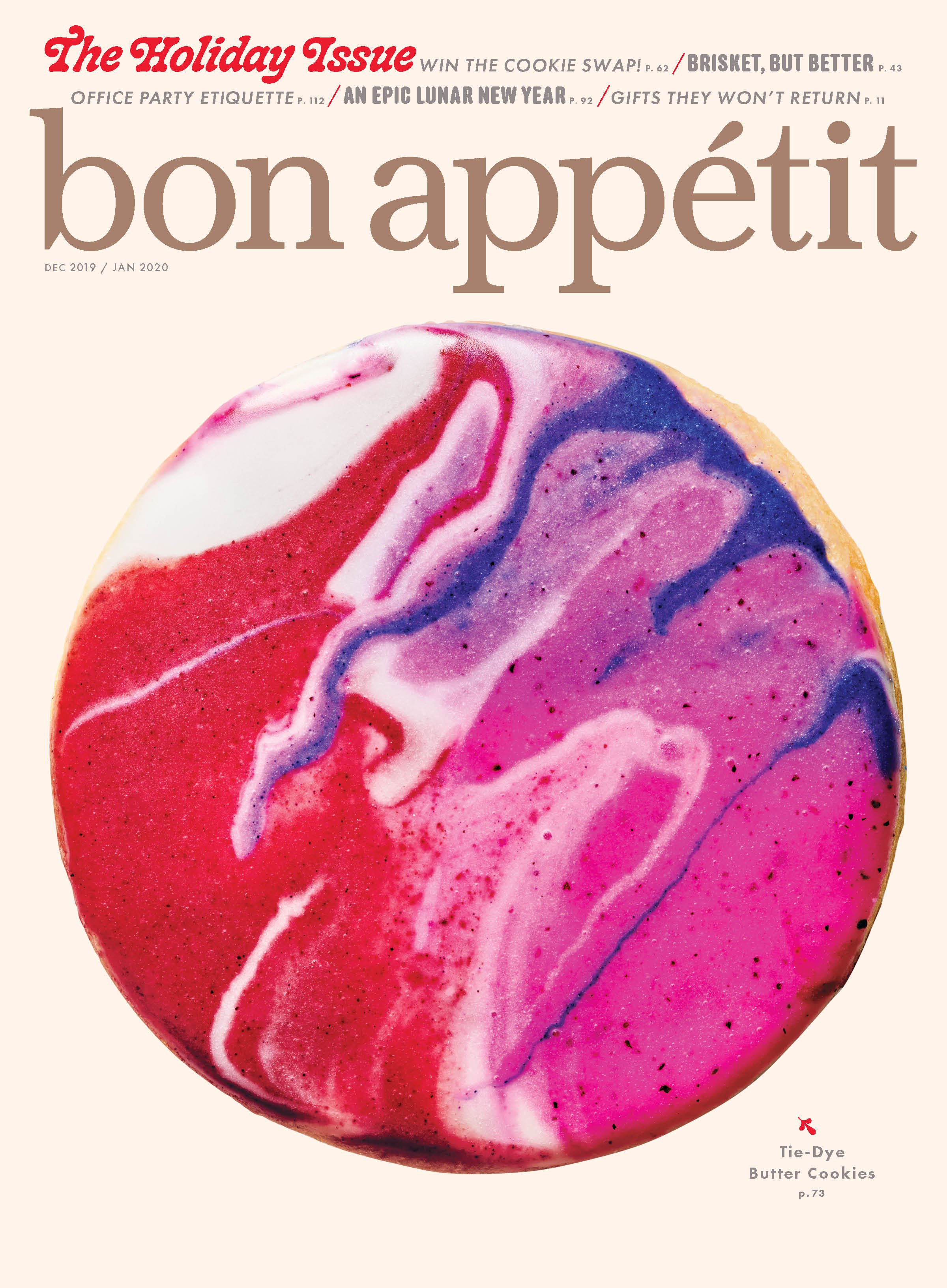

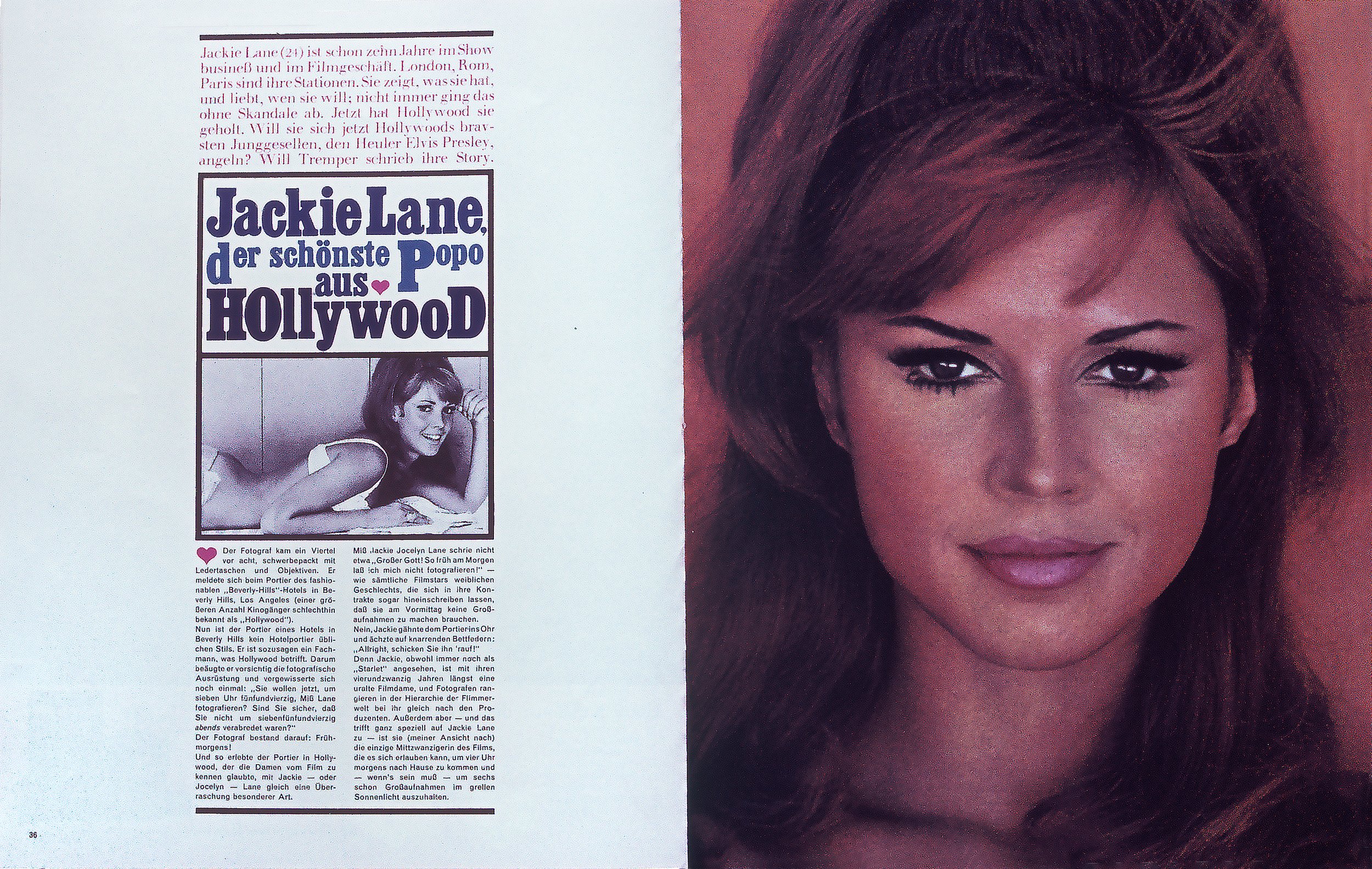

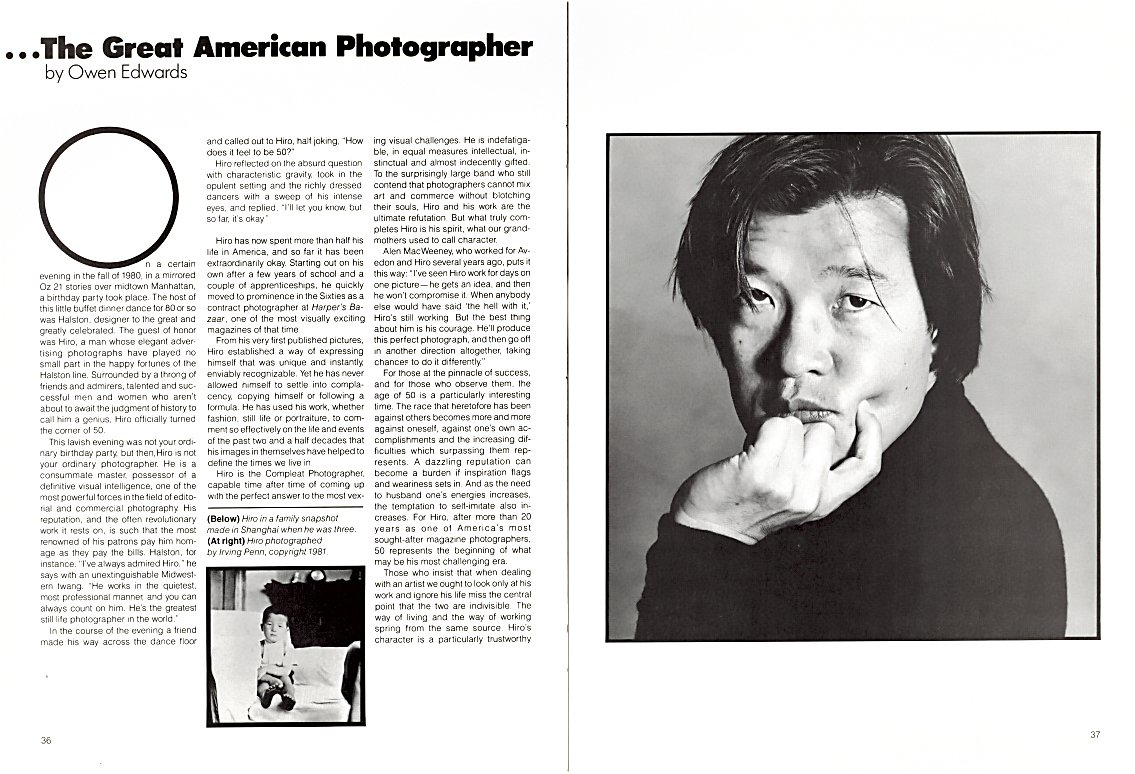

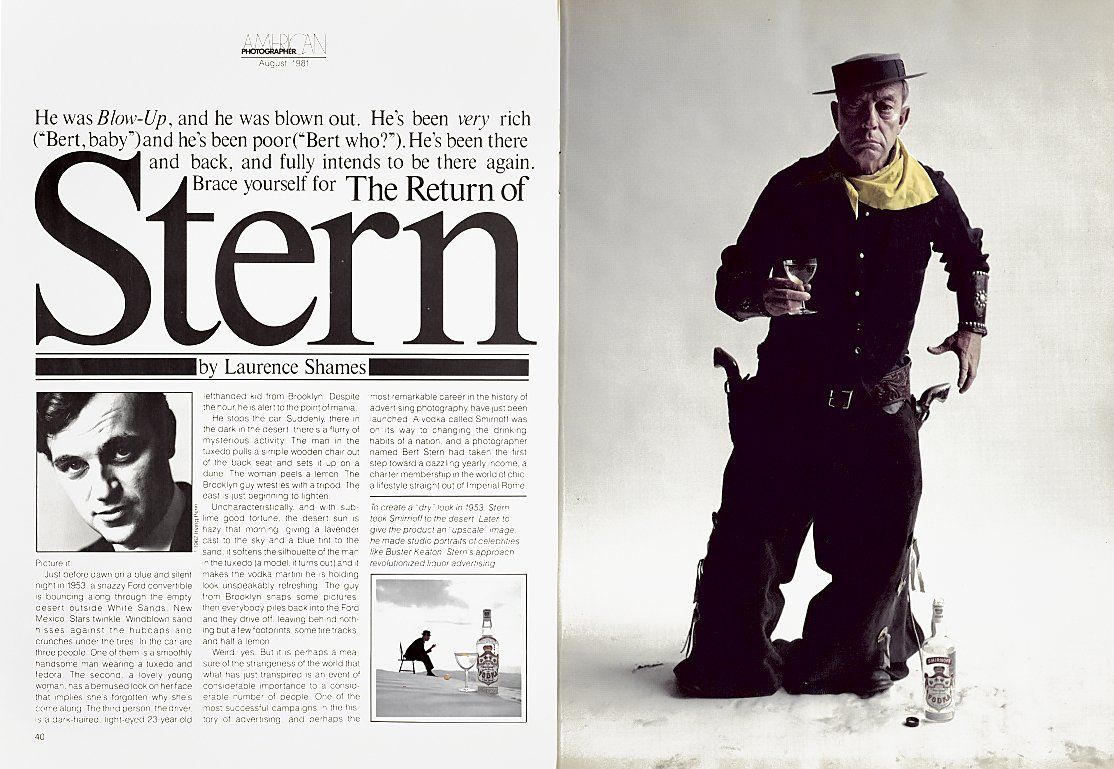

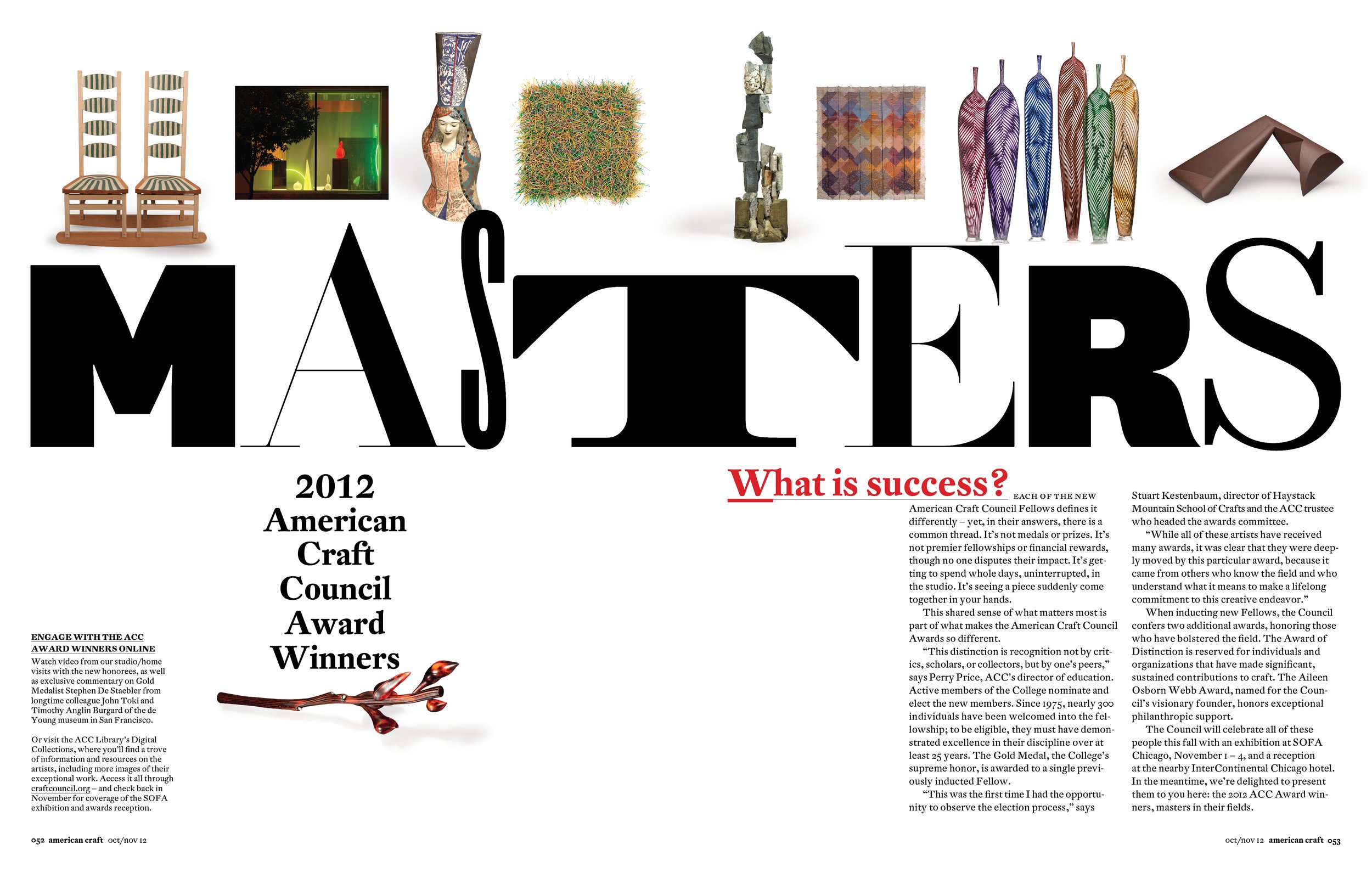

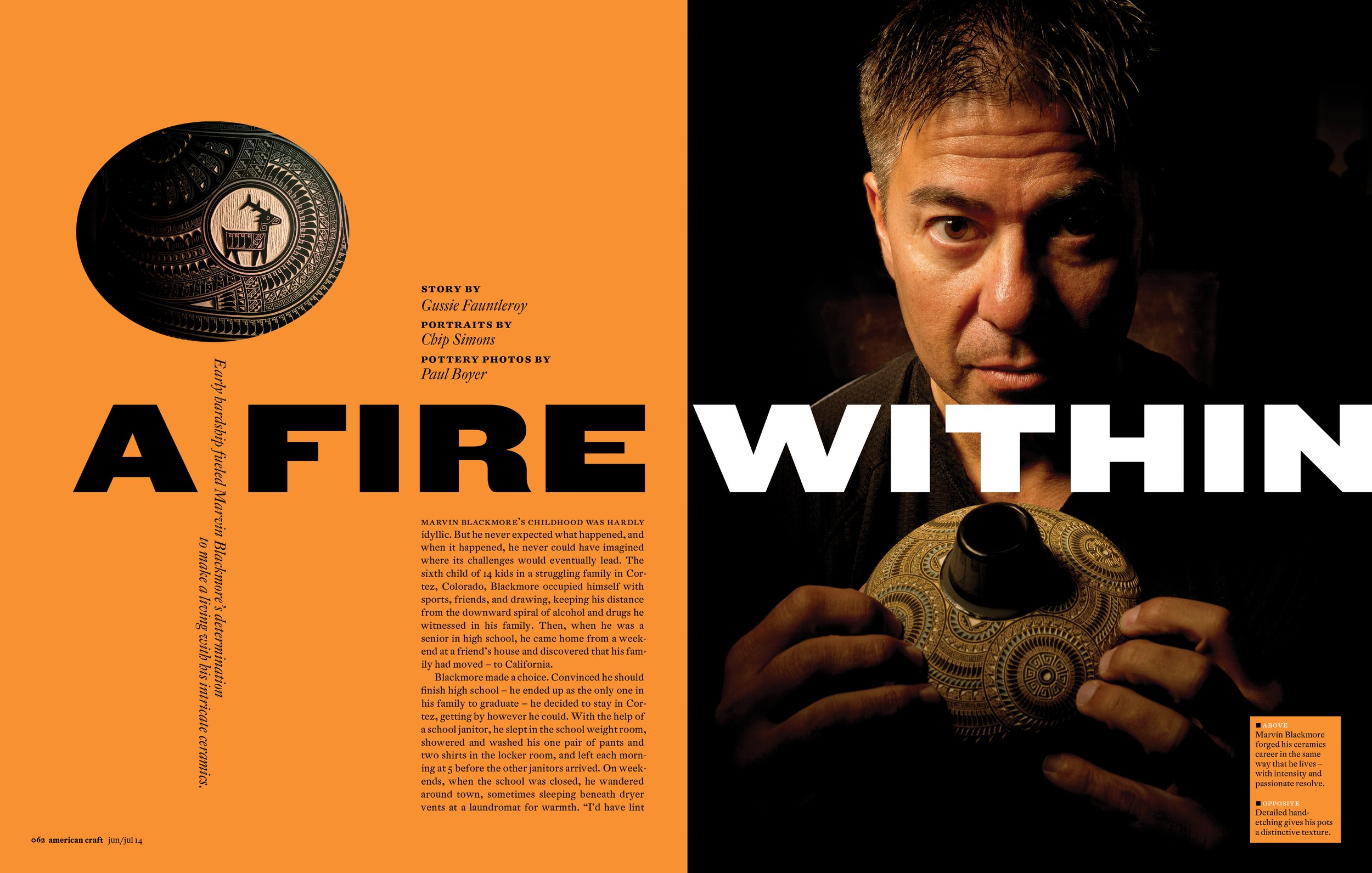

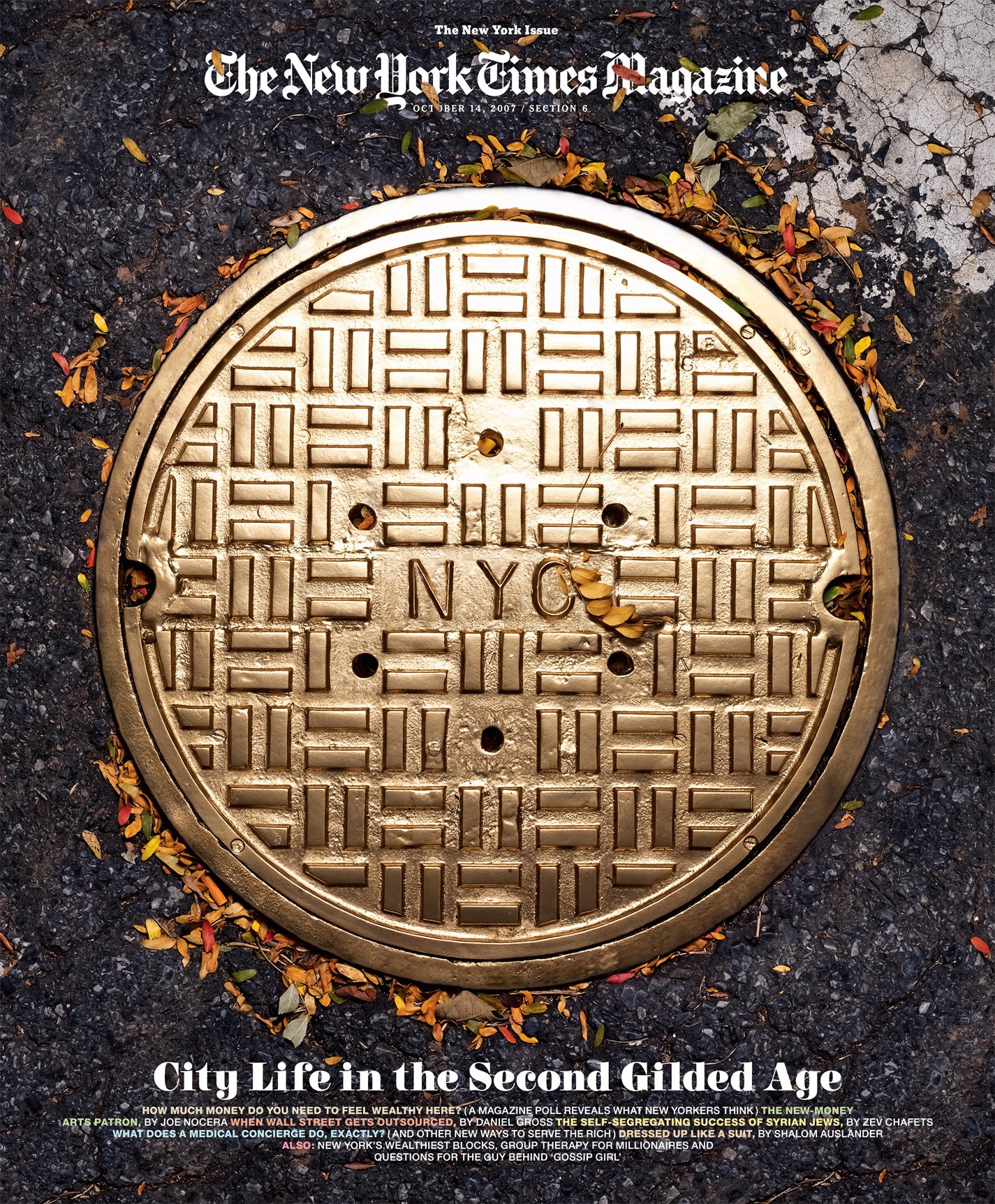

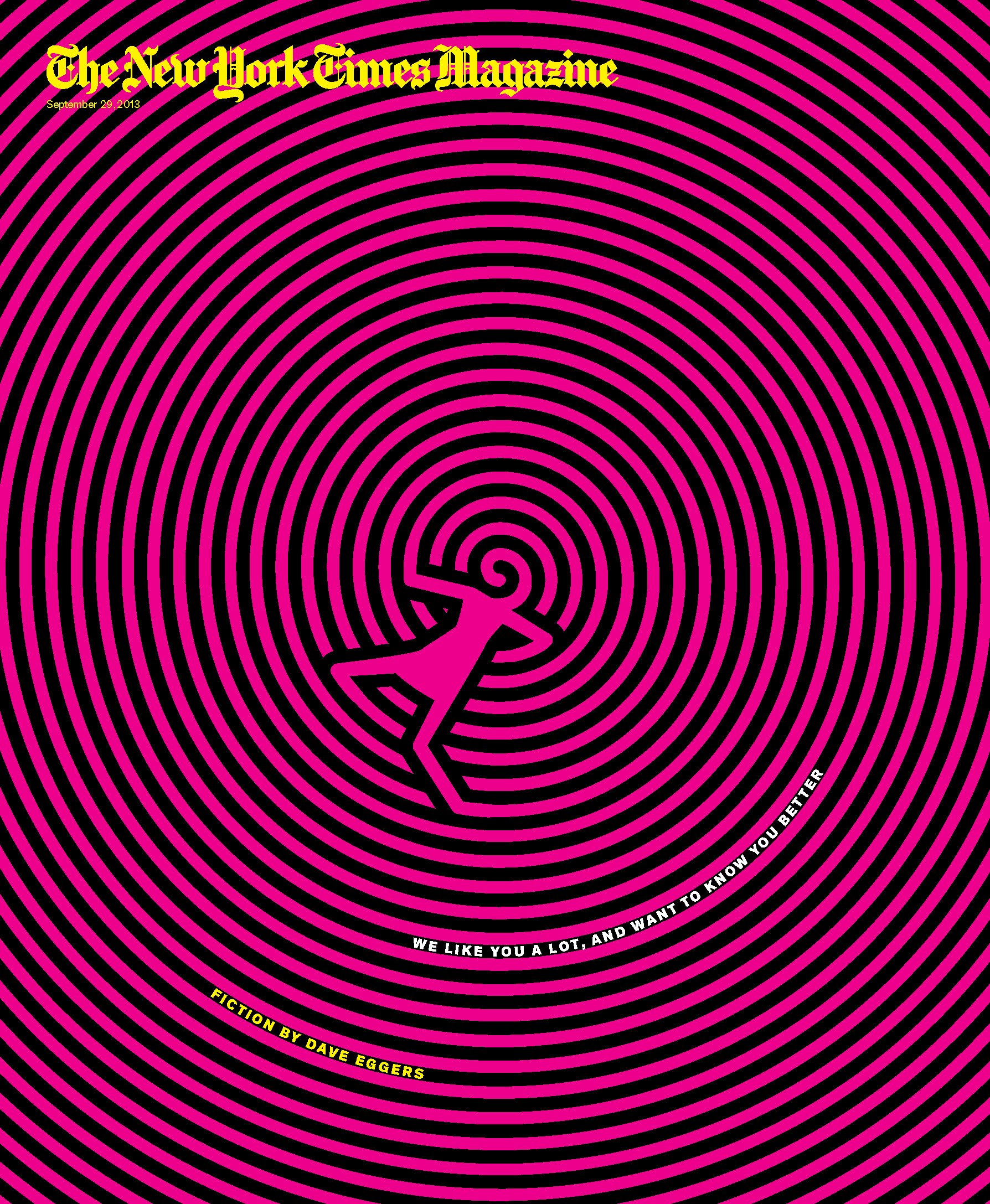

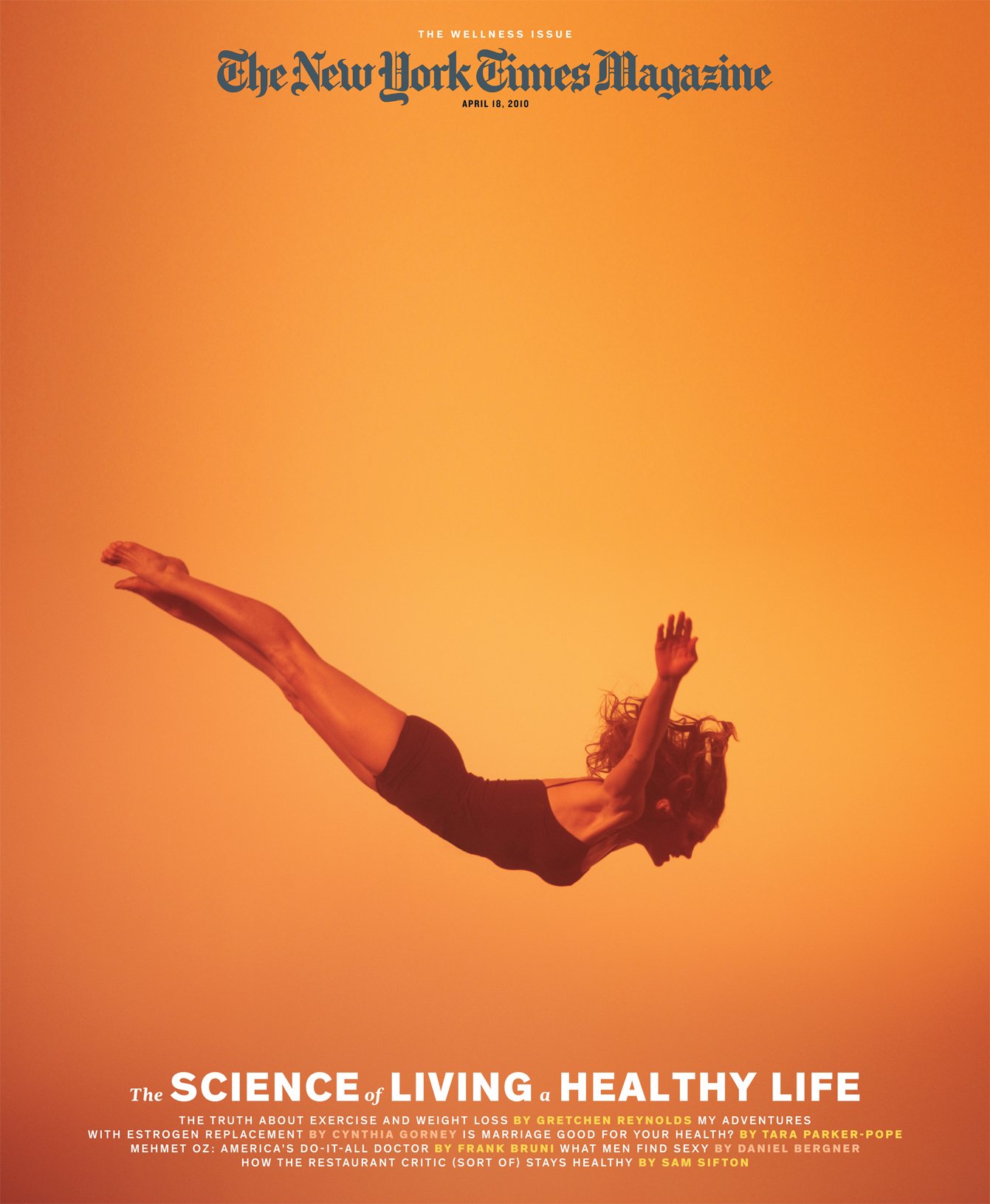

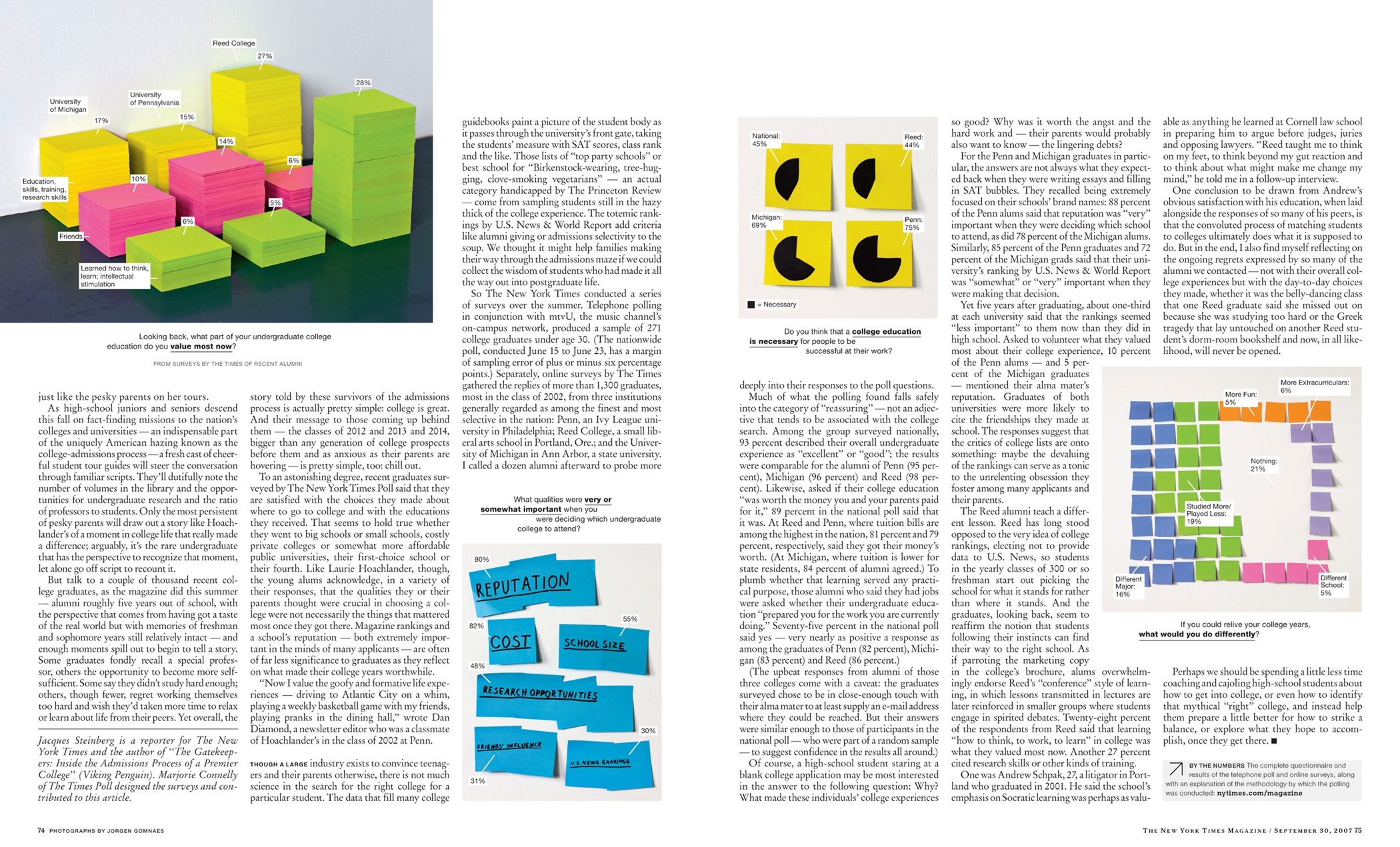

Covers from Dadich’s first tour, as art director, at Wired

“I remember my high school guidance counselor—and my parents—pushing me into following engineering as a path.”

Debra Bishop: At the age of 24, you were hired by editor in chief Evan Smith at Texas Monthly to become his next art director. Evan says, “Scott had a combination of charisma and seriousness of purpose and a bigness about his ambition. You could see from talking to him for a very short period of time, he had a plan. He had a plan for himself, and he had a plan for you.” Evan’s quote, I think, pretty much sums you up. Would you agree with that?

Scott Dadich: I don’t remember that quote. I don’t know where you found that, but that sounds right on the money, I would say.

Debra Bishop: But I have to ask what fuels these big plans? Where do you get this incredible drive?

Scott Dadich: That’s a really good question, Deb. I like making. I love being inspired by people around me, creative collaborators who do things that I just can’t even conceive of being able to do. So that’s always been something. An ambition to do more, do better, become more, build new skills.

But I think the other part of it is we just didn’t grow up with much. We had a really lean household coming up. And so it was really hard. And my dad had a bunch of health challenges. Early on I remember being very young and him being very sick. So my mom worked really hard to keep a head.

And I just remember as a kid, how hard that was on the whole family. So there was definitely a motivation not to allow that to happen to myself. And that I was just going to outwork and outperform in order to make sure that I’d be okay. And that those around me and my family would be okay eventually.

Patrick Mitchell: So how did you get yourself in front of Evan—and was DJ involved in the hiring?

Scott Dadich: Yes, absolutely. So DJ came to Frank and Jane Cheatham’s—one of their design lectures. We’d have alumni and folks out in the world doing interesting things come in and visit and guest lecture. And there was a cork board that was like the DJ shrine that was always there.

There’d be the latest Texas Monthly cover and some layouts or posters. And they kept that updated as I recall. And then one day Frank said, “This guy who you walk past his work every day is going to be in and going to give a guest lecture.”

And I remember sitting in that—that was another big click moment: Oh, not only could I do this for a living, but do that in particular—magazines and Texas Monthly—this thing that’s been on my parents coffee table growing up. That was a big moment.

And I just made it a point—when DJ came in he just enraptured me—I made it a point to get to know him, and foster a friendship, and actually get his email. And I chased him. And I was also working at Texas Tech at that point, in the chancellor’s office. So I was working on this magazine called Vistas, which was a science magazine, the alumni science magazine.

So I was in school and working, but DJ was really a vector, like, That guy is amazing! And I’ll do anything to learn from him. And I invented a couple of reasons—and my boss at the time, a guy named Artie Limmer—we both, like, built some boondoggles to go down to Austin and photograph DJ. And we did an ad campaign about prestigious alums. And just a chance to be around him and learn from him more.

And it was through that process we built a really strong friendship and stayed in touch. And I would email him, call him for advice and thoughts. And when it came time for him to move to Pentagram, and he made that decision, he shot me a note and he said, “There’s going to be some change around here. You should definitely get your hat in the ring.”

Patrick Mitchell: How long a period of time are we talking about—from the time you went to see him talk?

Scott Dadich: So probably three years total from the time that I first met him at that guest lecture to the time where he was moving to Pentagram. And he was just extraordinarily generous in both recommending me and making sure that I knew about the opportunities that were shaping up there.

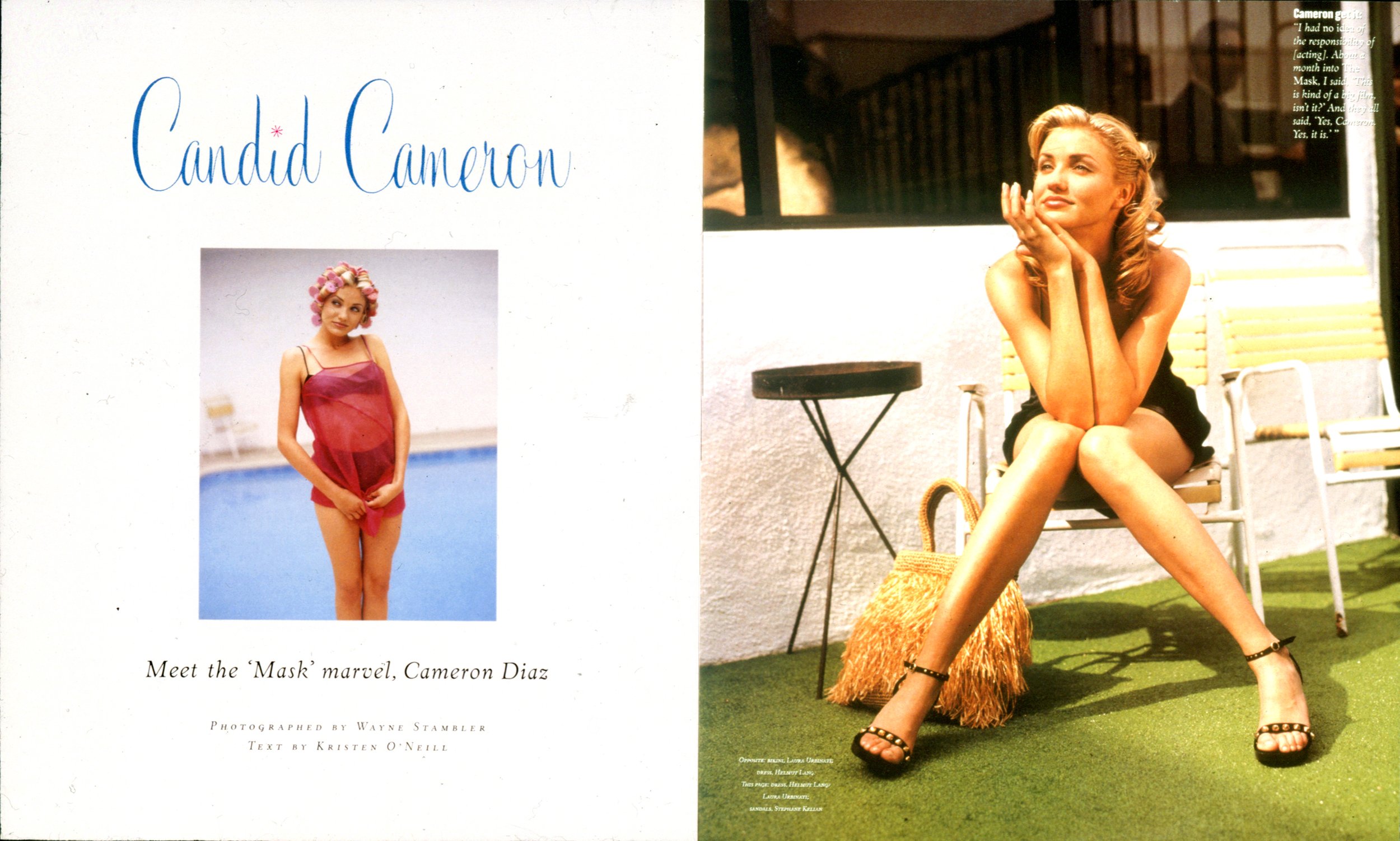

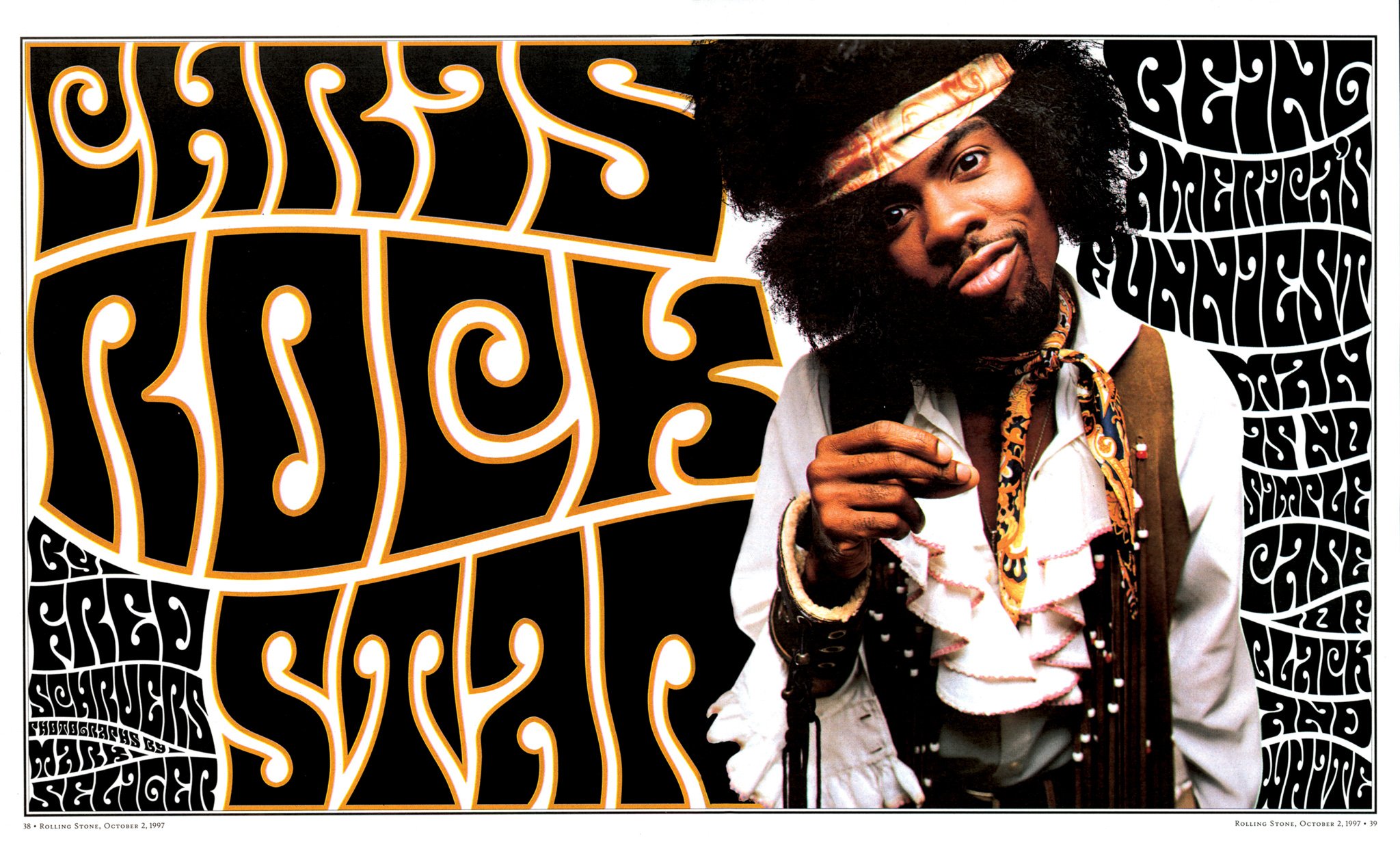

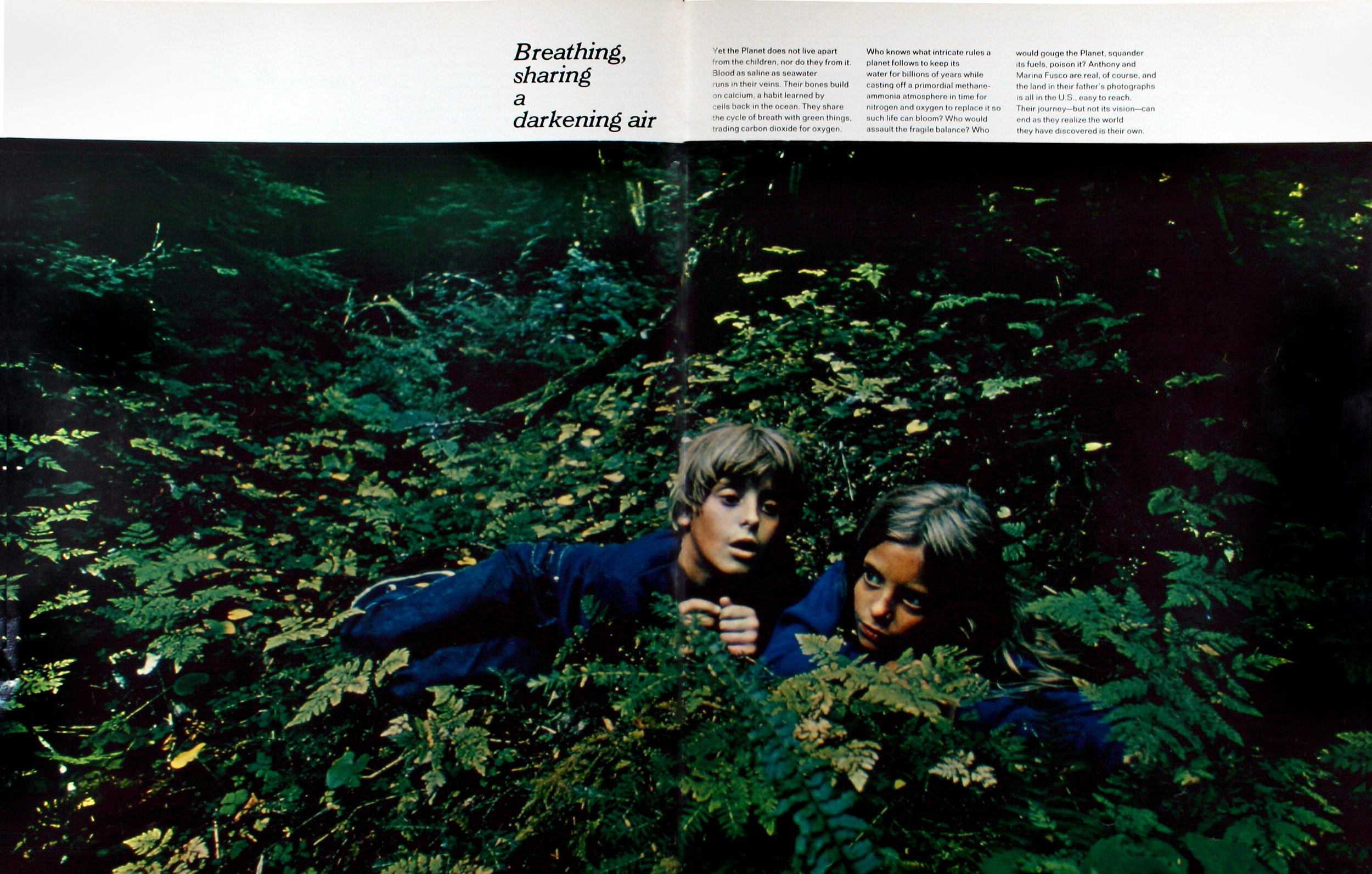

Patrick Mitchell: I’m excited we are going to be able to show some of that work on our website because, there’s just something about—yes, I grew up there. Texas has its pros and cons, but as a city/regional magazine, there are not many others of those that can make the kind of stories that you can make in Texas. And I know you've made a lot of friendships on these just unbelievable photo shoots you went on. These are some pretty fundamental relationships that you created while you were there. You want to talk a little bit about those guys—how their friendships sort of guided your work, and career, and life?

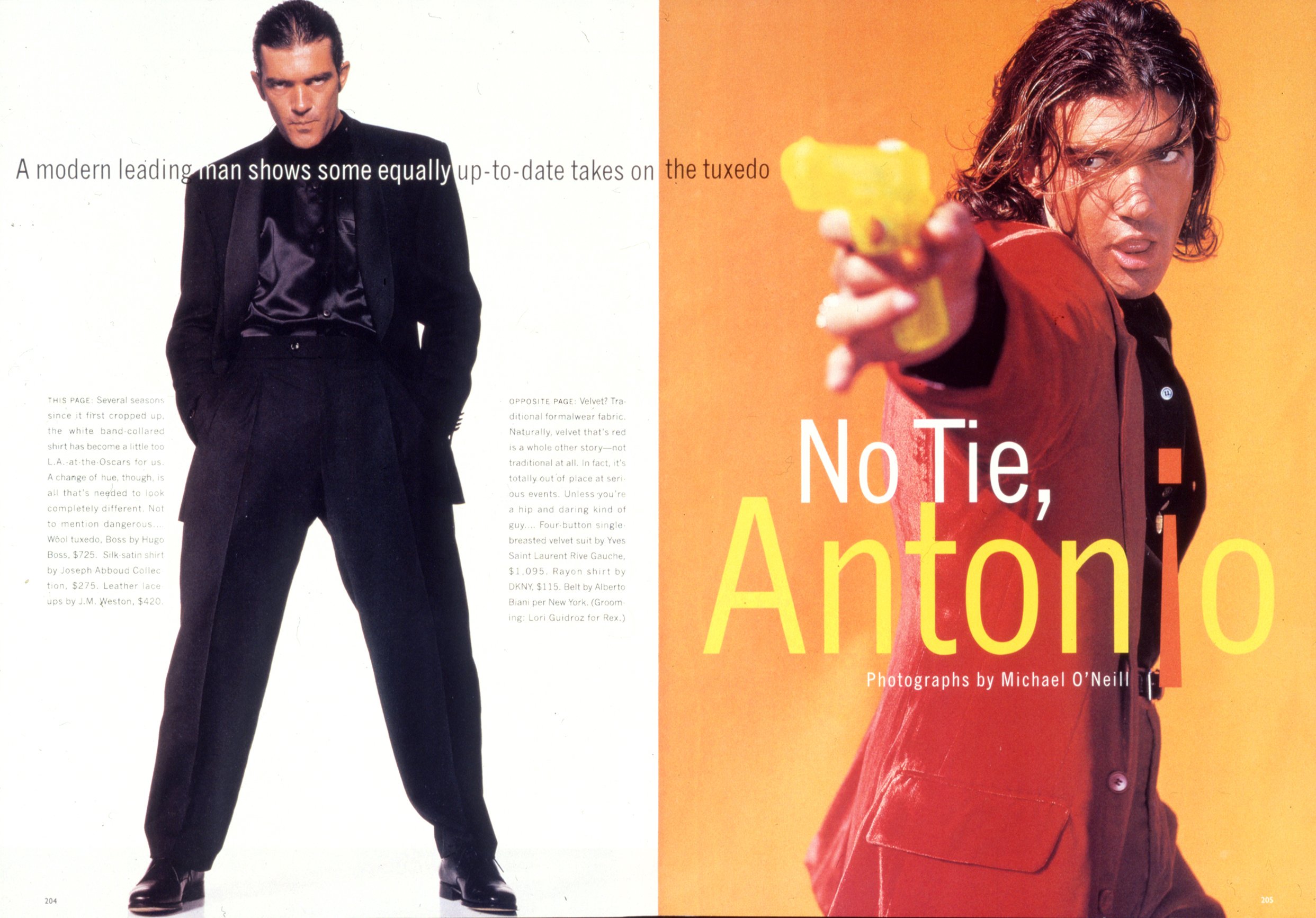

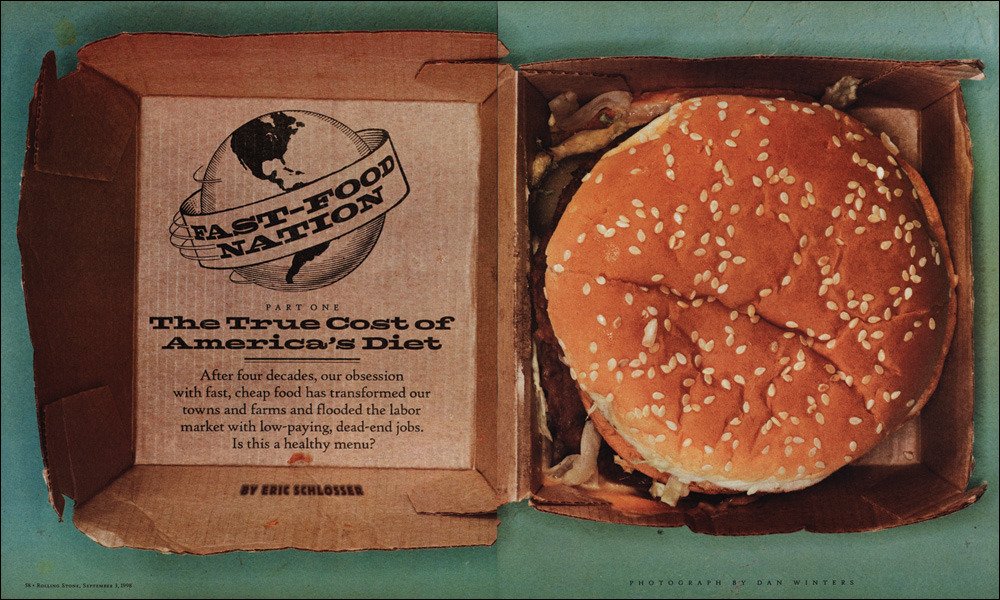

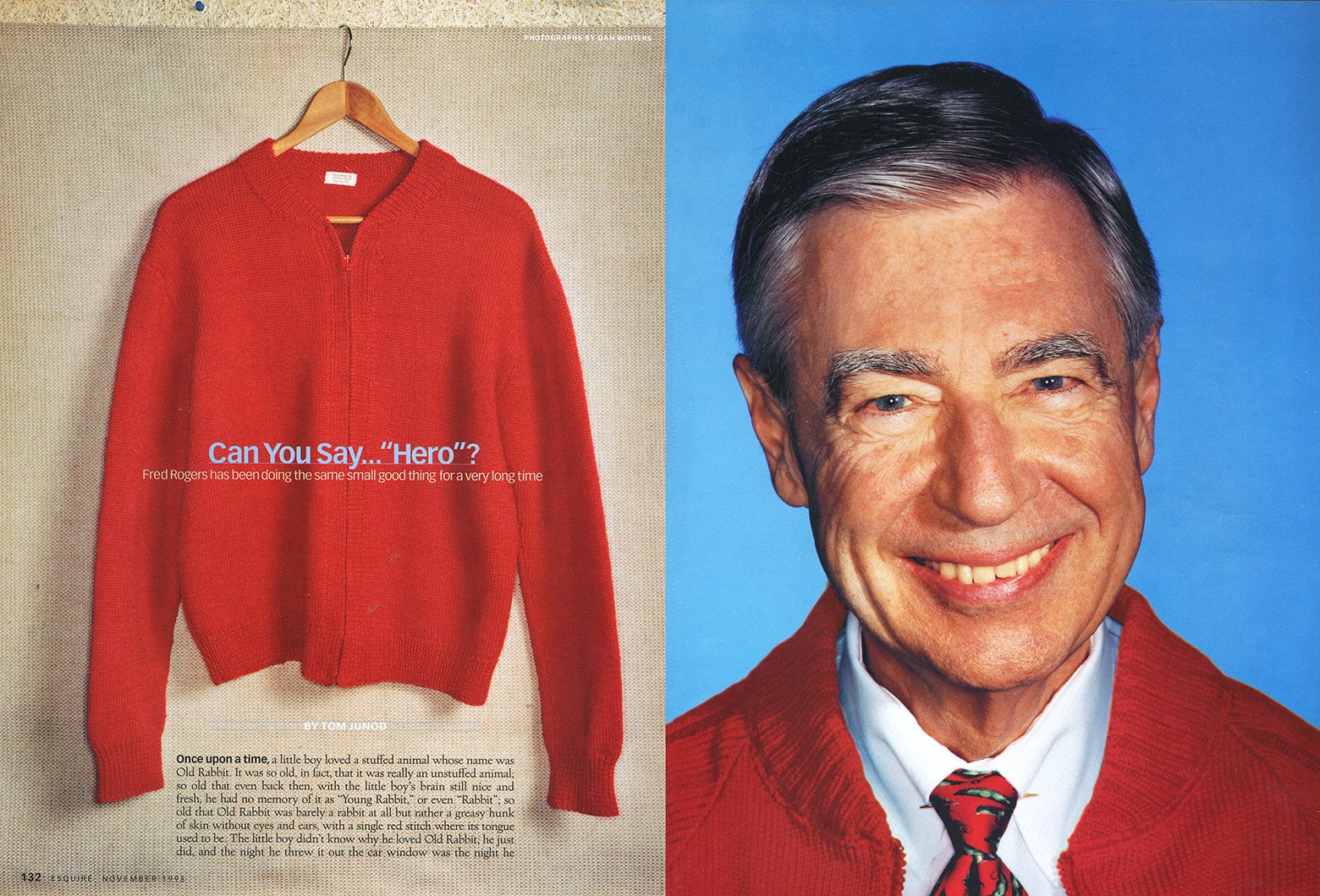

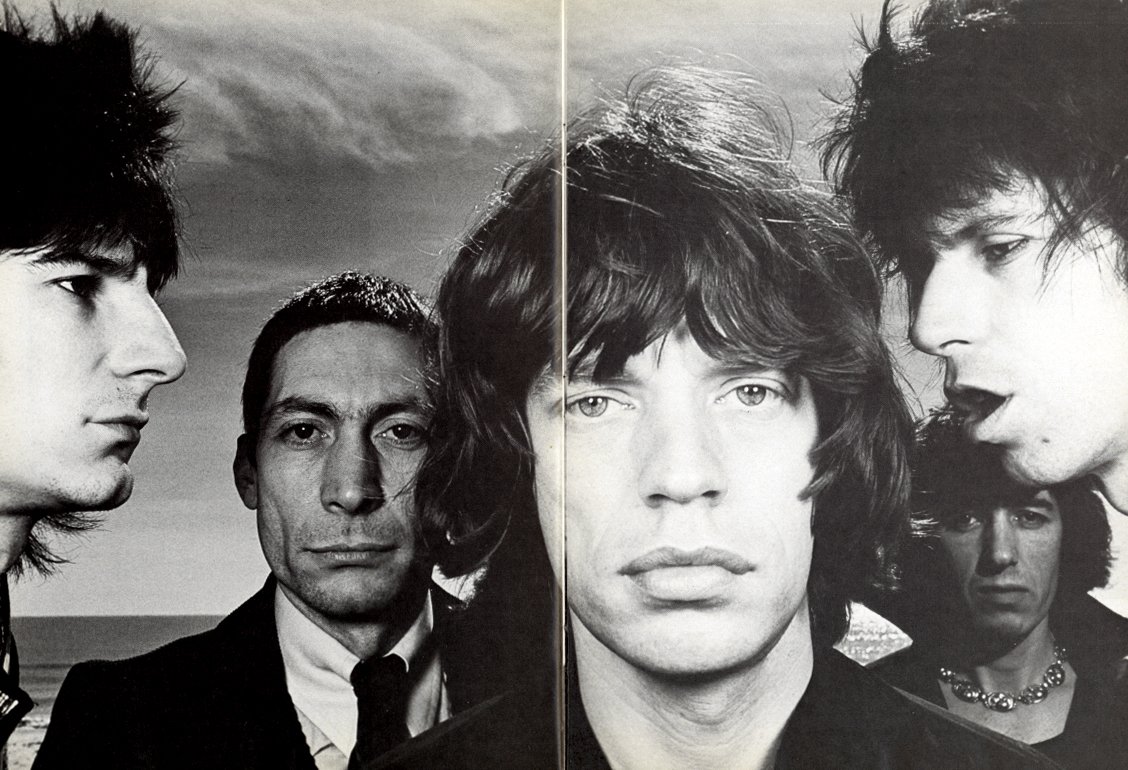

Scott Dadich: Yeah. I count those relationships, those friendships, as some of the most important events, moments—bits of luck—that I’ve ever experienced. You know, the reason I’m going to Austin in a couple weeks is to sit down with Dan Winters and work on a new book together.

I remember the legend of just his renown and his presence because seeing DJ’s Texas Monthly and the incredible work that he and Dan had created together, to get to know Dan—that was also one of those, I must get to know Dan. I must work with him.

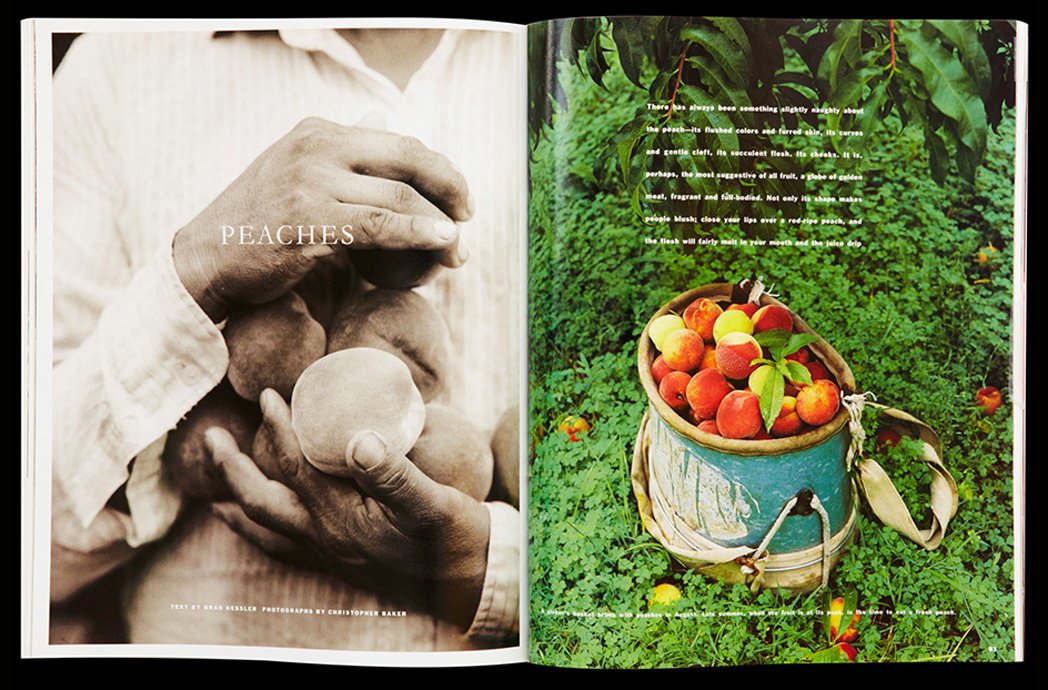

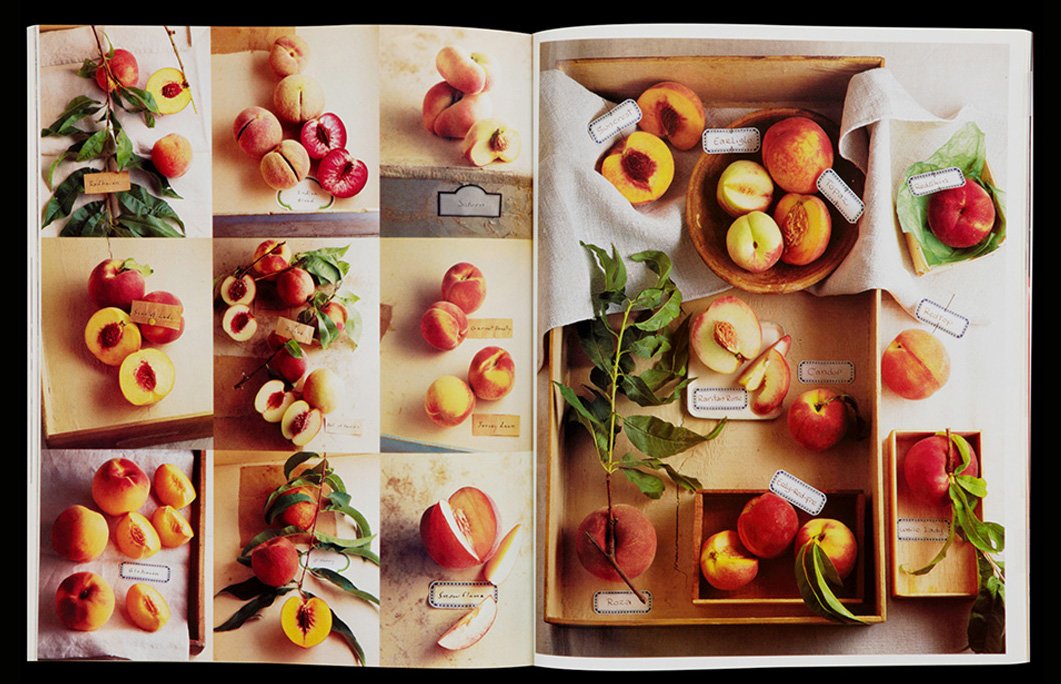

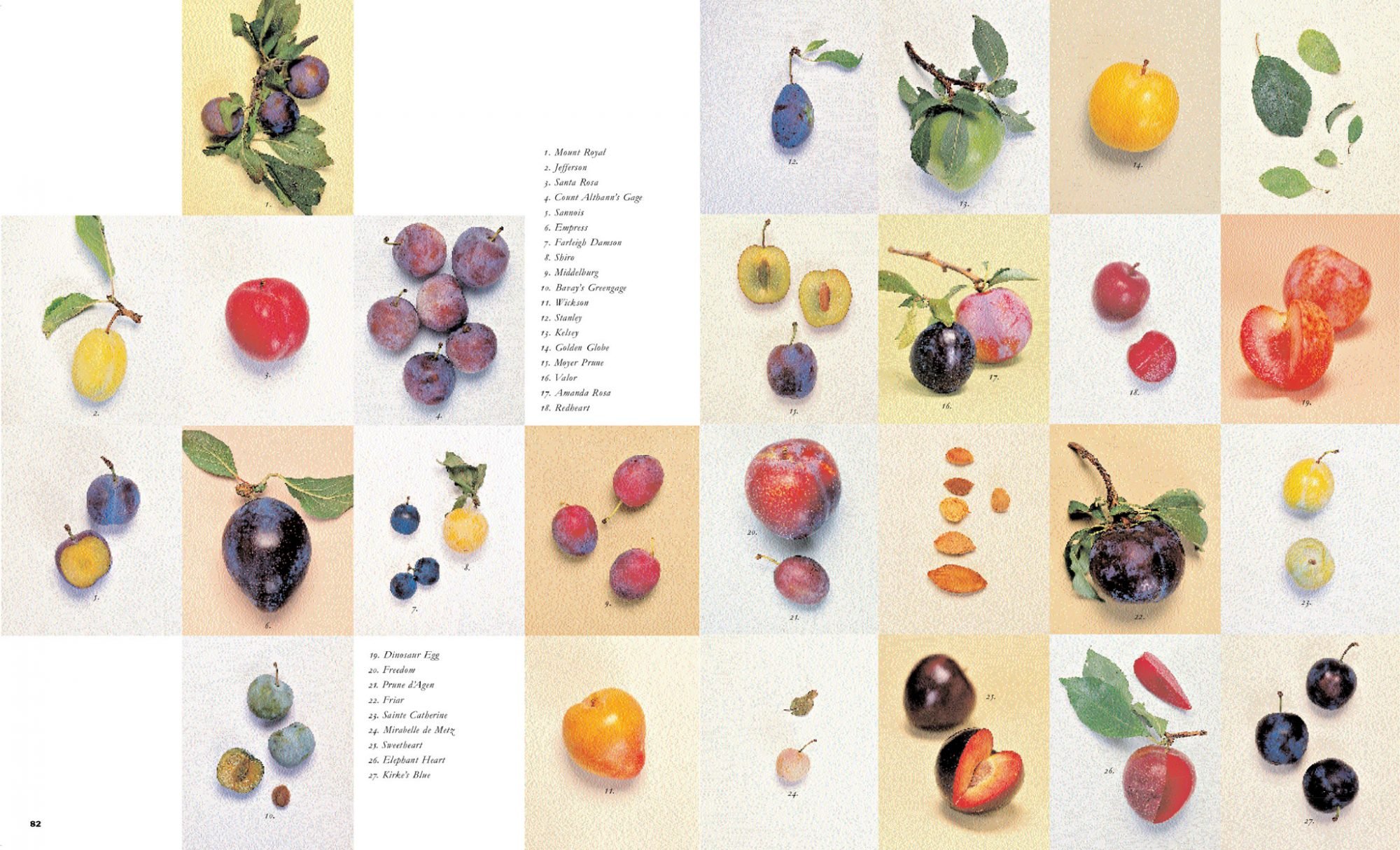

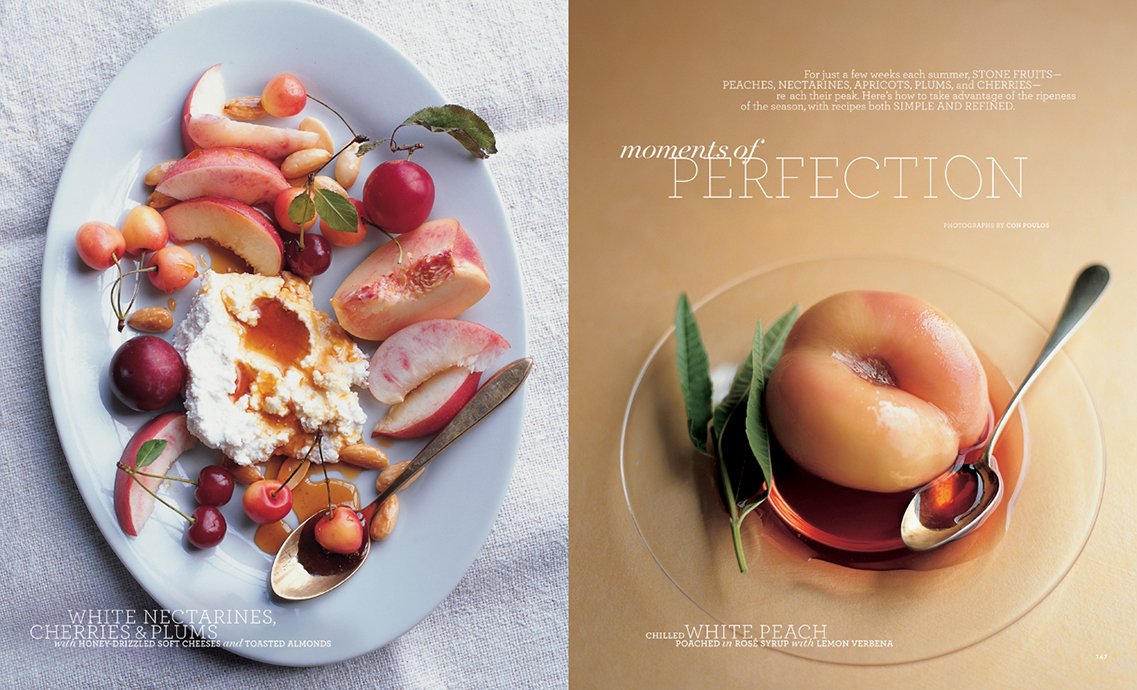

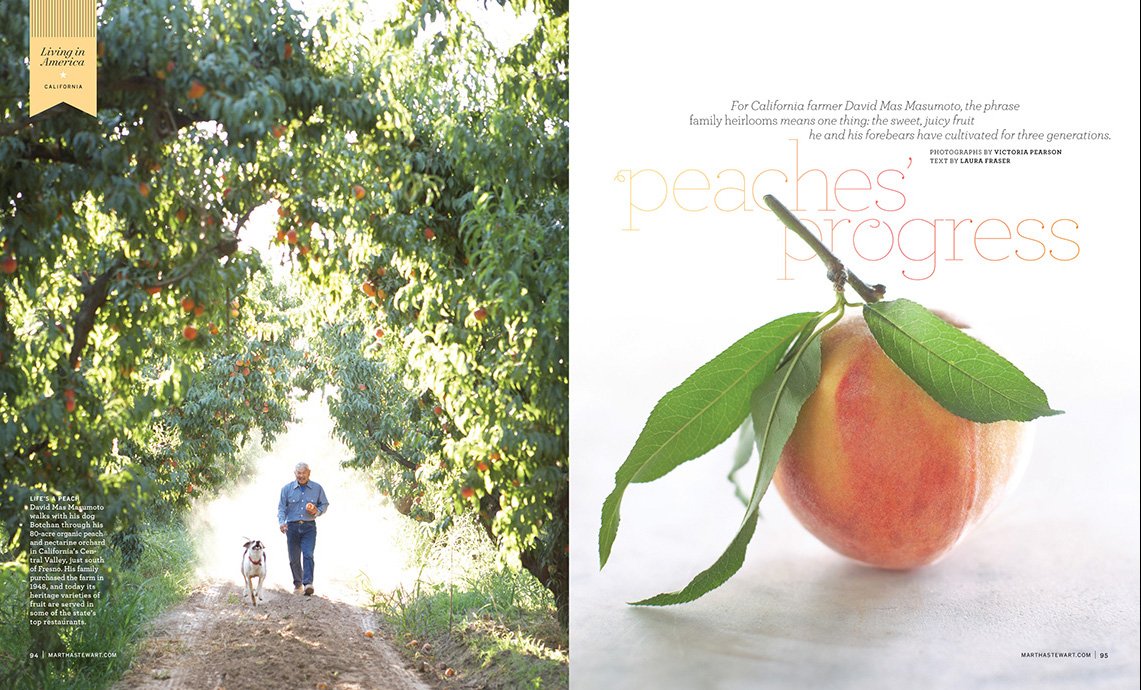

So I pitched a photo essay on peaches. It was a June issue—again, Patrick, the joy of Texas is the diversity of storytelling that we get to take on. Let’s just celebrate how amazing summer peaches are. That was going to be—and certainly a rip down from Martha Stewart to be able to do that. But to go to Dan’s studio—we went and picked peaches all afternoon and then photographed them—was one of the most incredible, creative afternoons ever.

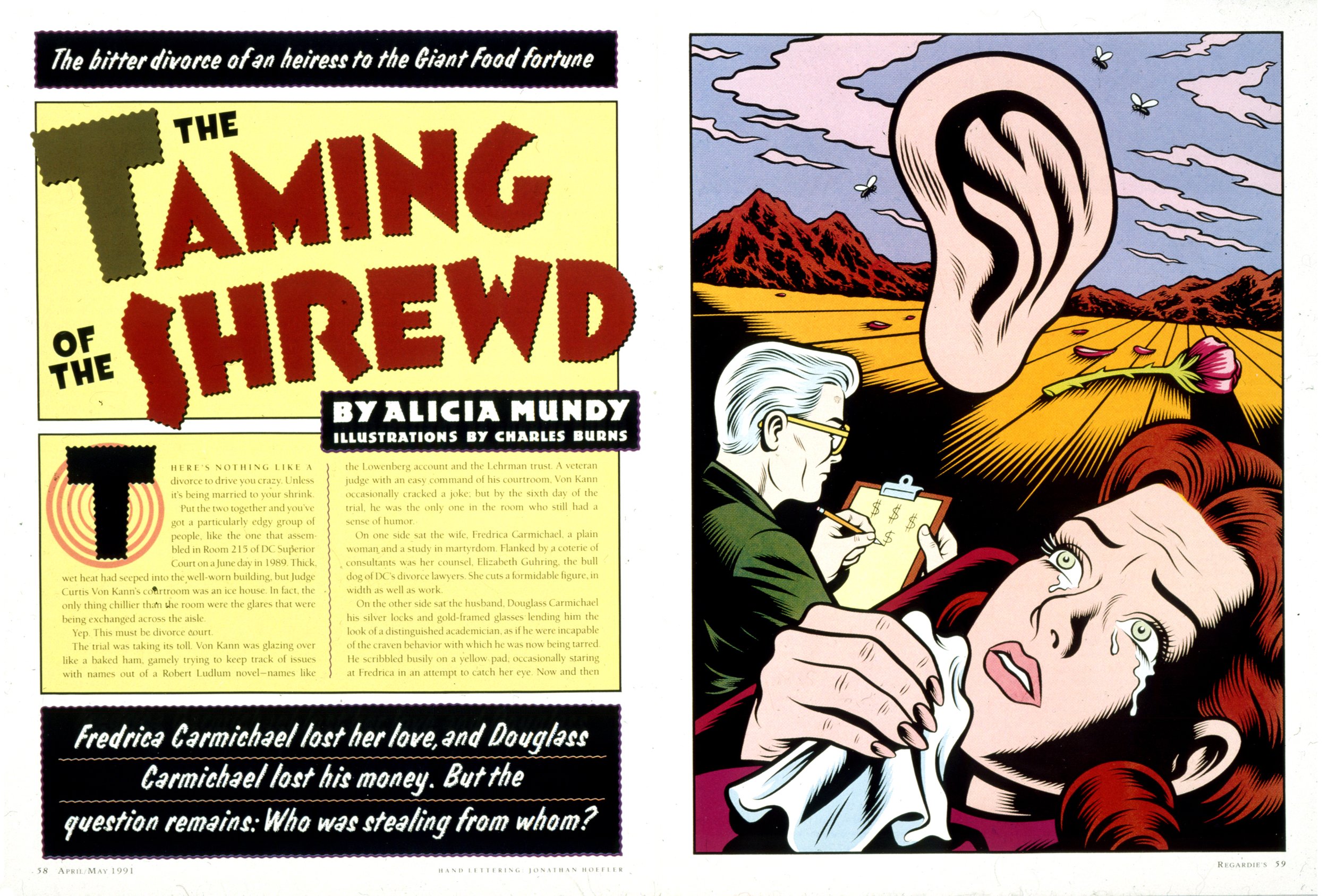

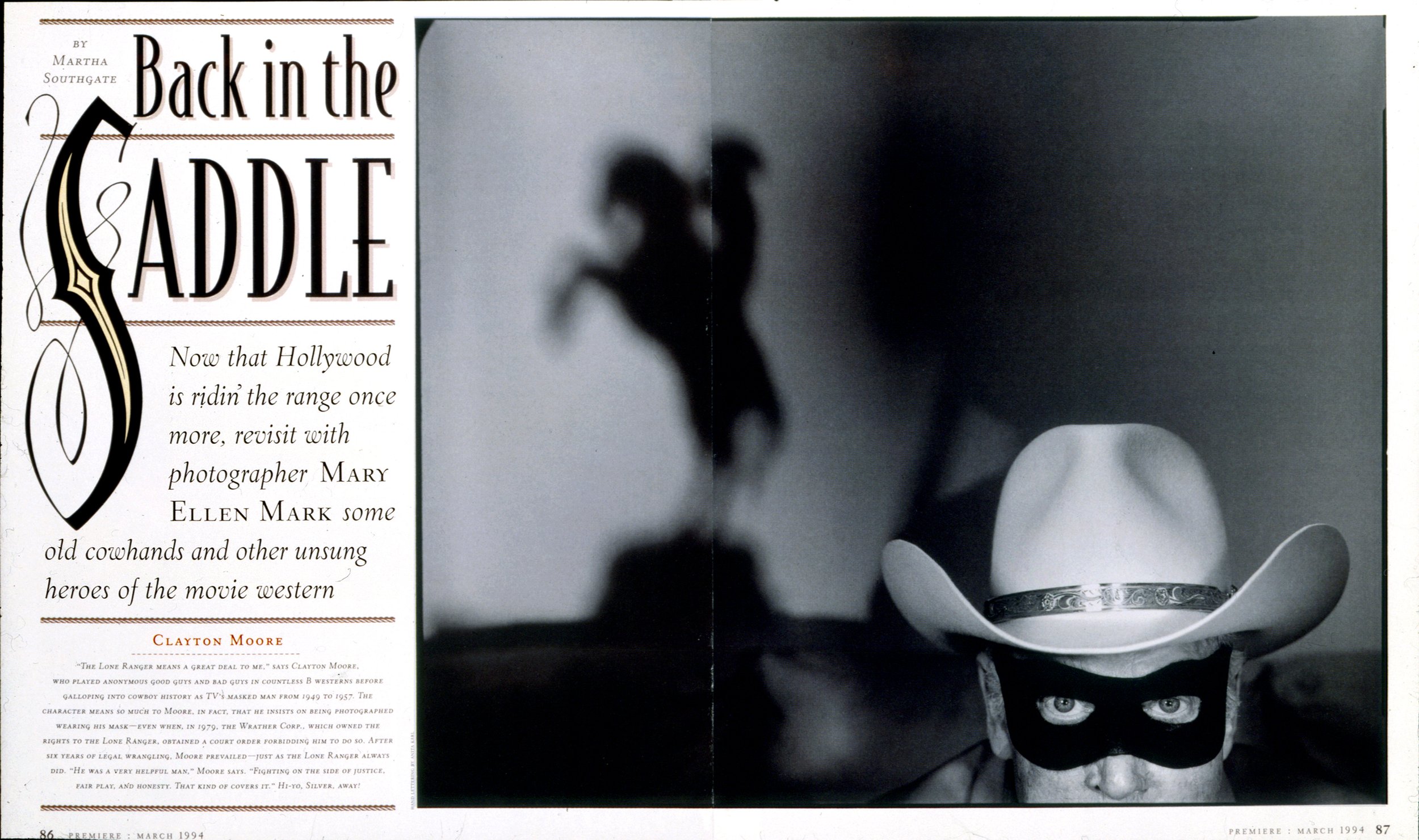

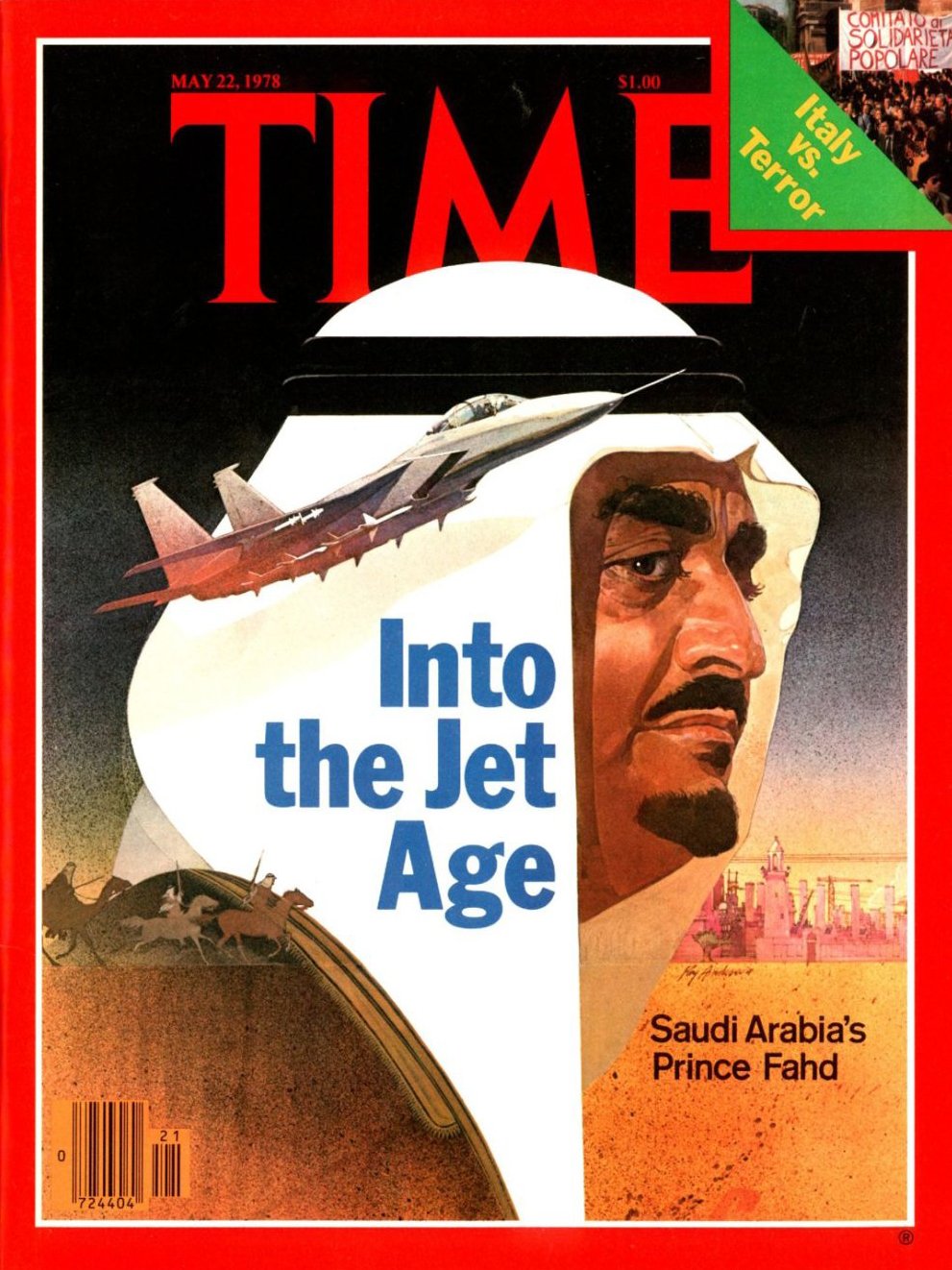

And Dan and I still talk about that. Or Platon—getting the excuse to shoot Karl Rove. That was another thing that happened at Texas Monthly. The world came to Texas when George W. Bush became president. And when he started running for president, the world’s attention turned to this guy, this character.

And Evan earned a position in a national and global conversation because of those events. And so when Karl Rove, as his chief advisor, is in the White House, that to me, having been a huge George magazine fan, gave me the reason and ammunition to call Platon and say, “I think we’ve got our first job together.” And then very shortly after that, George H.W. Bush, during the Iraq war.

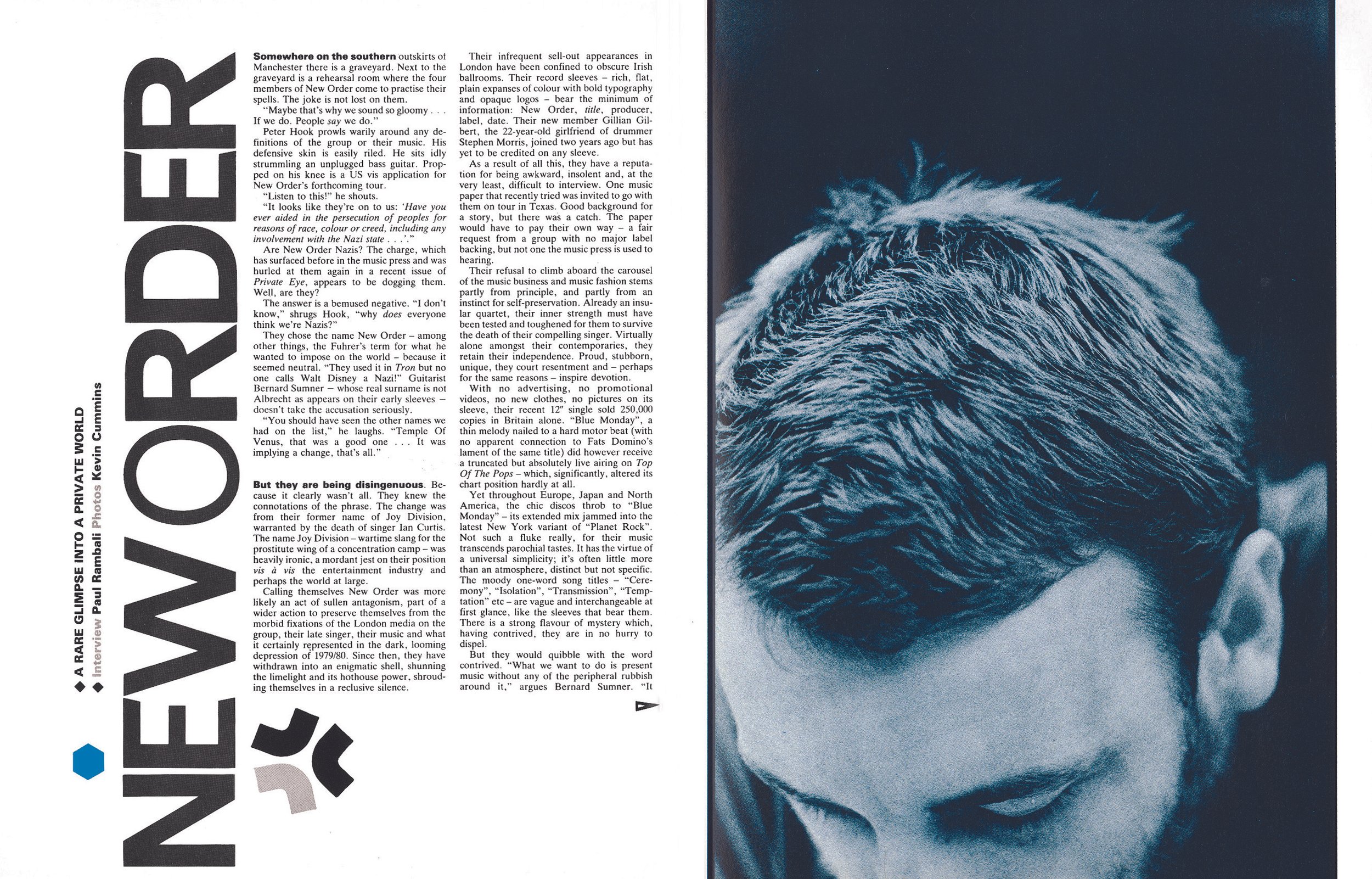

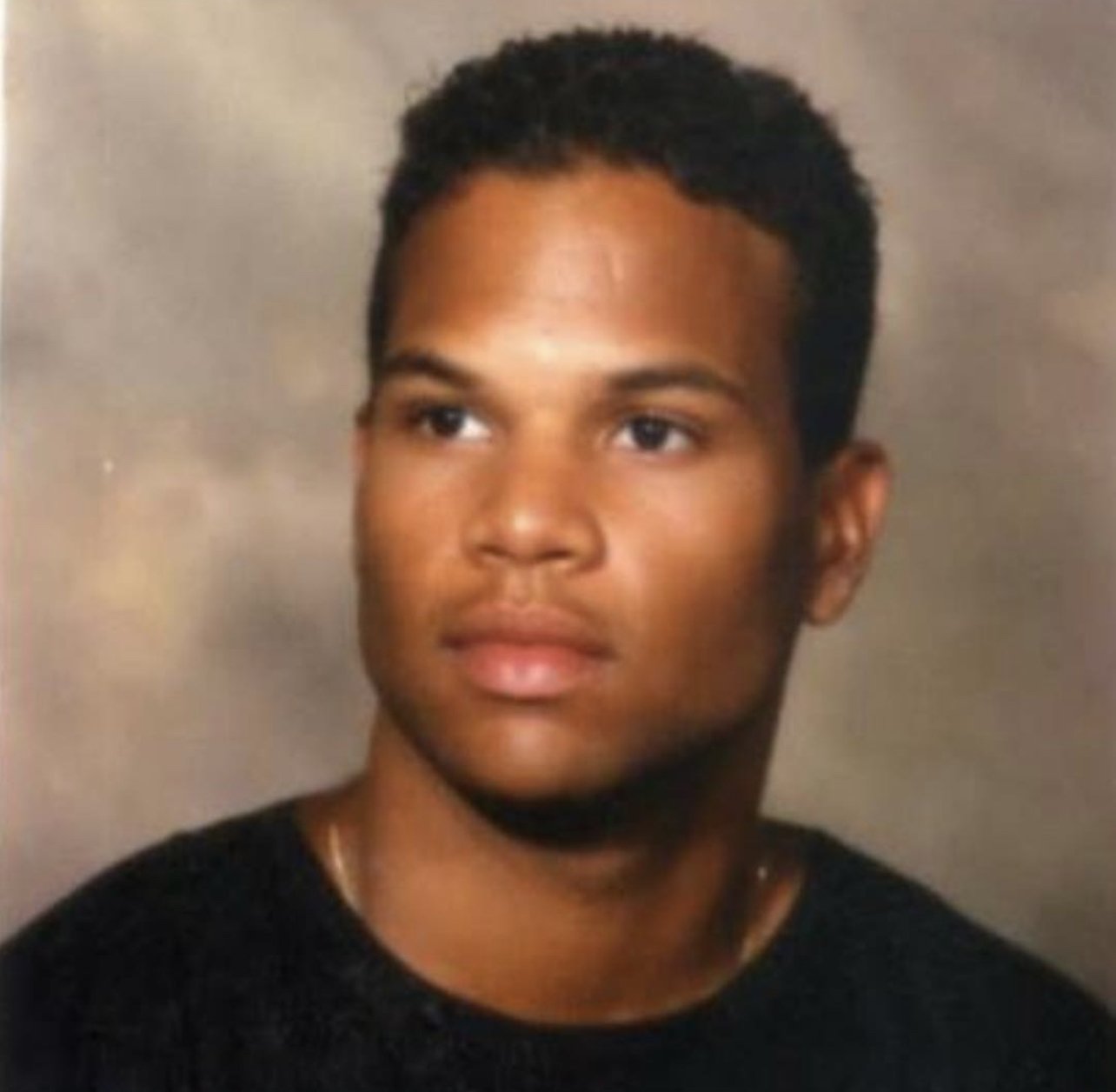

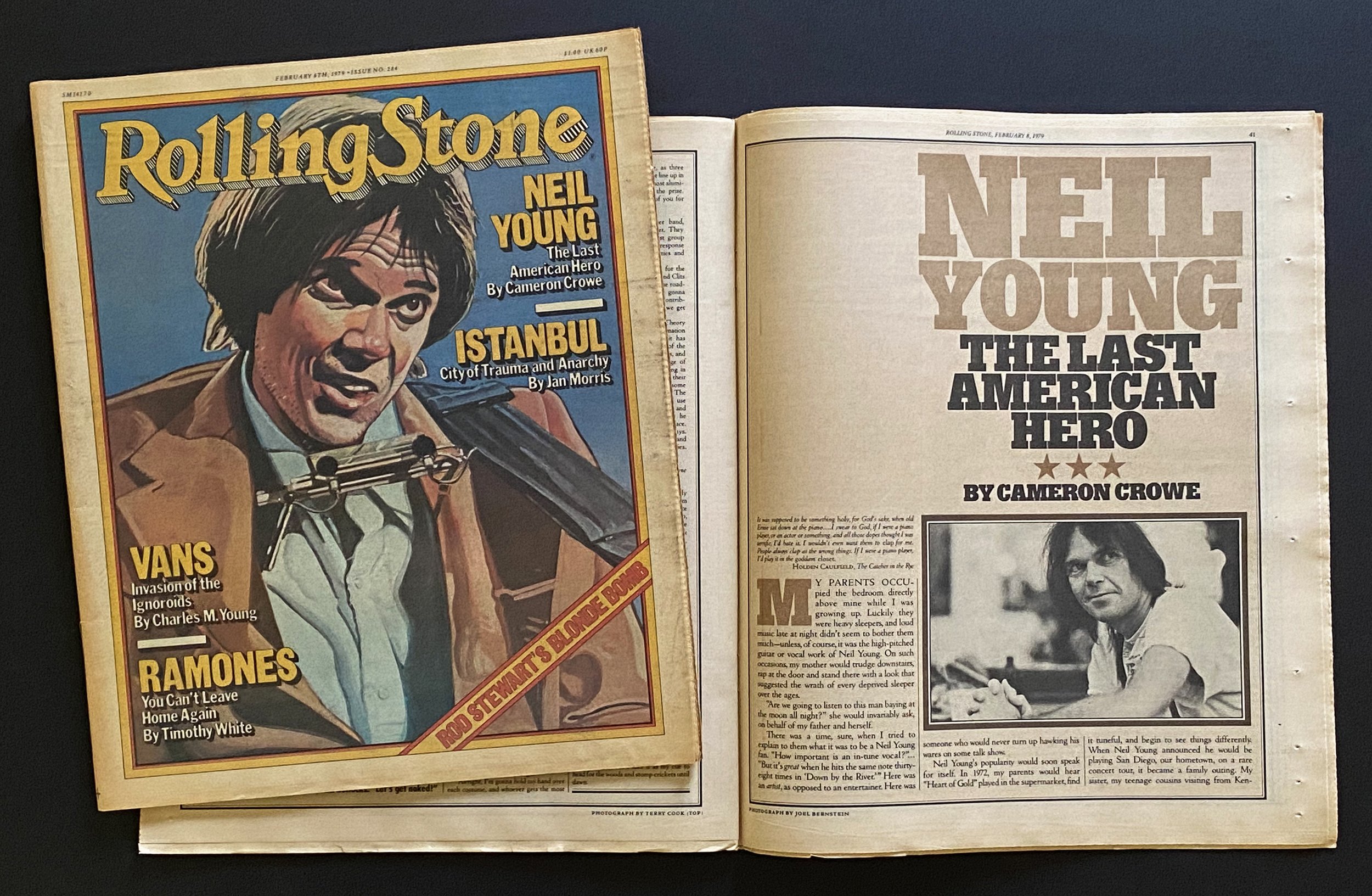

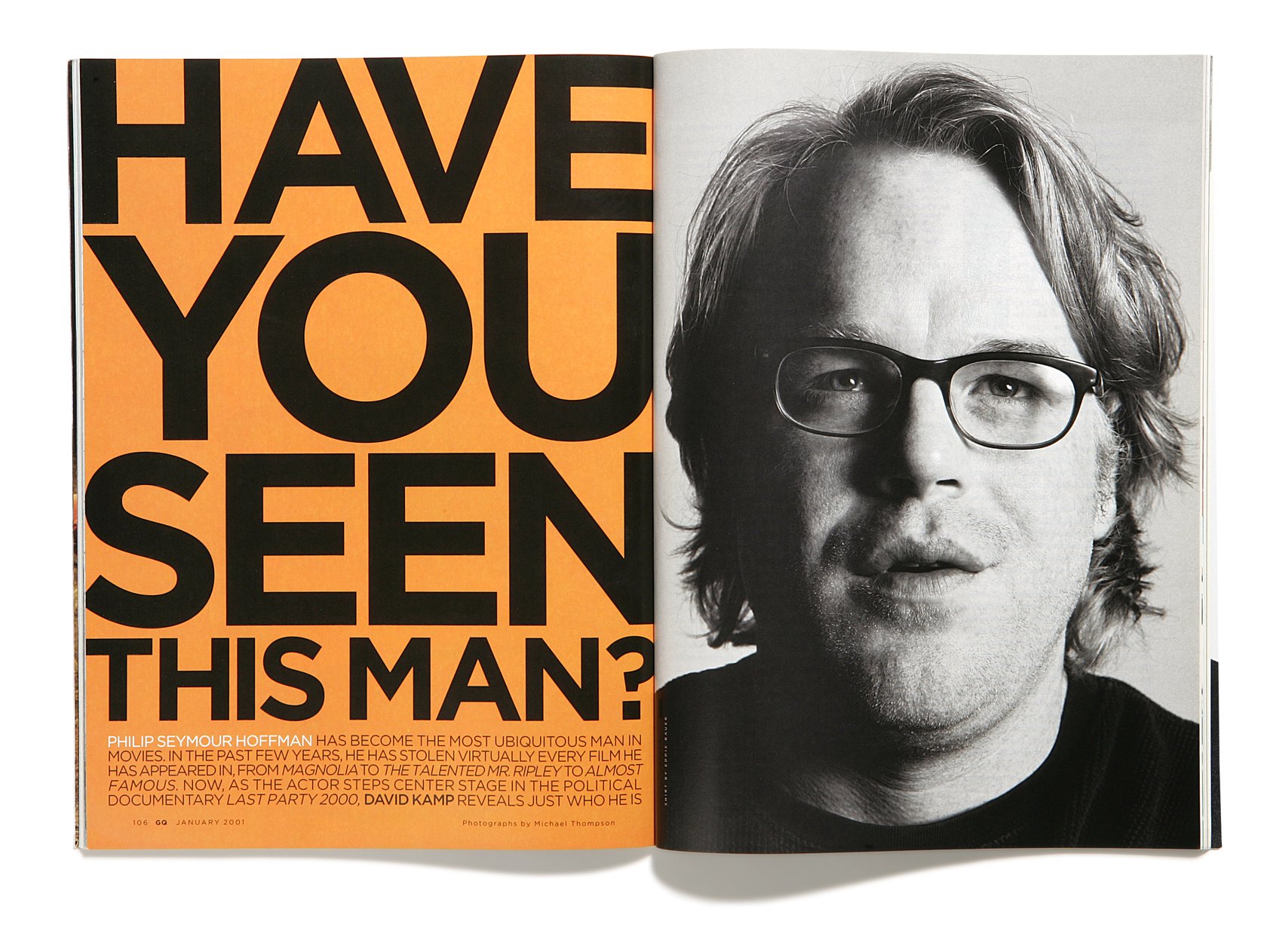

Patrick Mitchell: All right let’s move to Wired. At a certain point Chris Anderson hired you and you were replacing Darren Perry? That’s such a blast from the past. A really great guy. And I think he died very young.

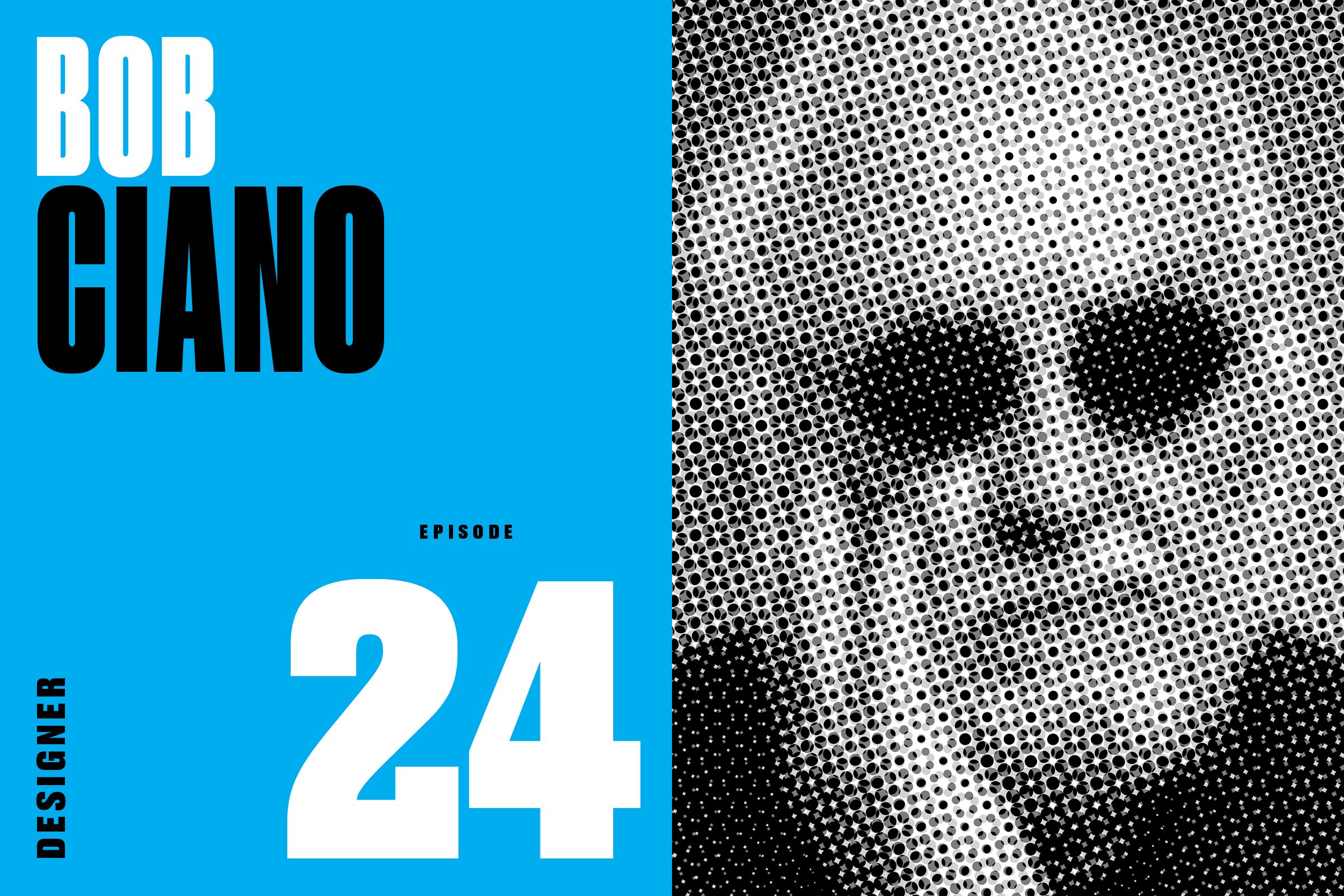

Scott Dadich: He did. Darren had died and it was very traumatic for Wired and for that community. And I revered Darren’s work. And it was, I believe, almost a year that the role was unfilled. Bob Ciano was actually sitting in, sort of caretaking. And I remember interviewing, not only with Chris, but Jake Young, and Bob saying, “I’m just here to get this thing through and to get its next leader seated.”

So there was a lot of emotional freight that lived in that decision and that role. And I felt a great responsibility to care for Darren’s legacy, but also for what Wired had meant to me growing up as a magazine fan.

“It was one of those things that I just wanted to just press into the magazine foundationally, that you could only do the following things with the following choices and the following typefaces.”

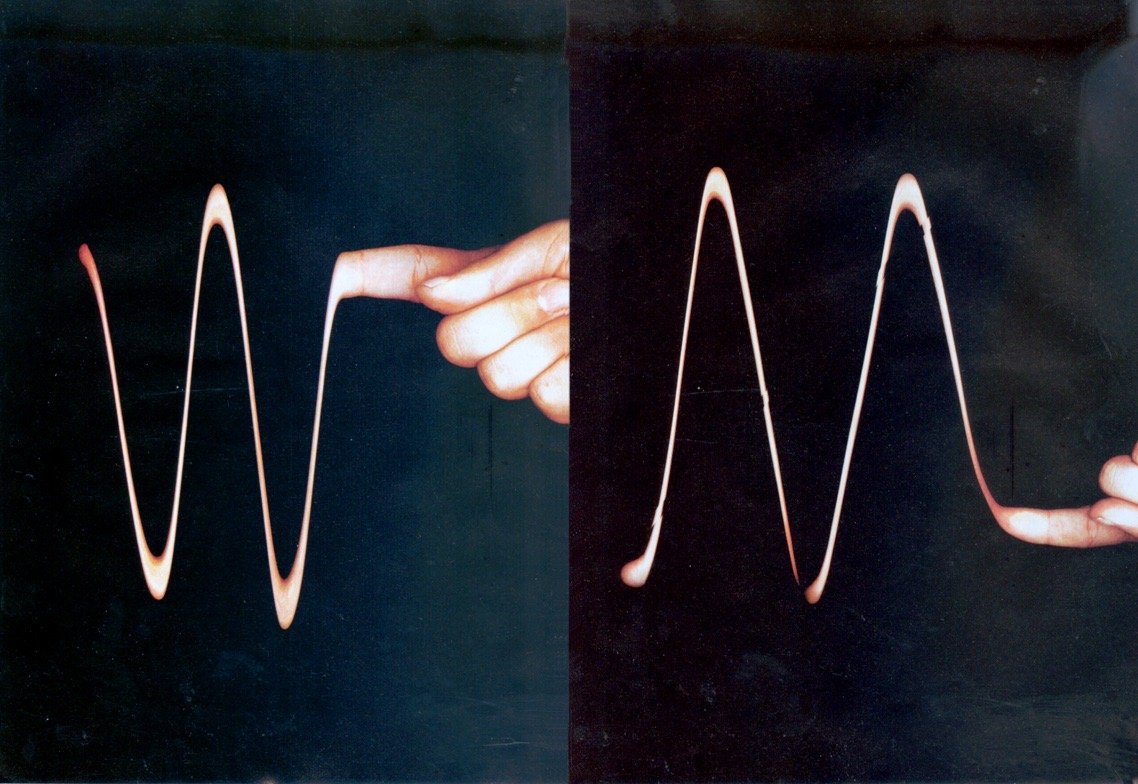

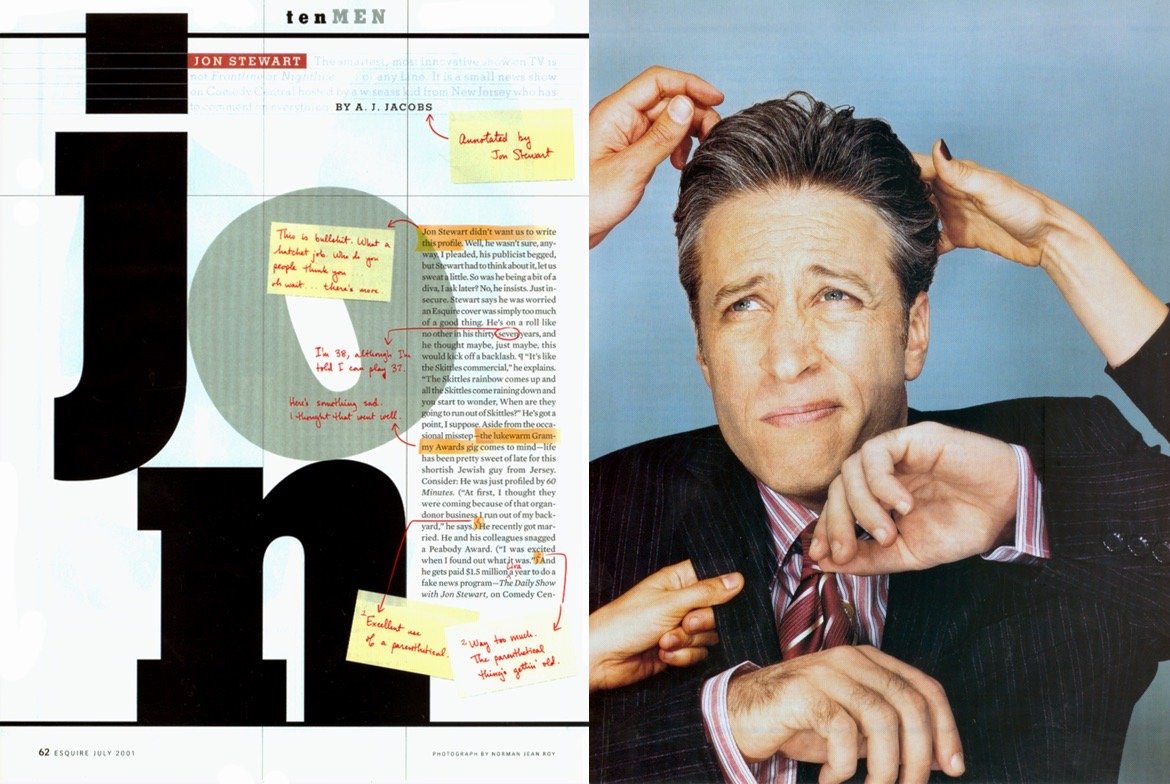

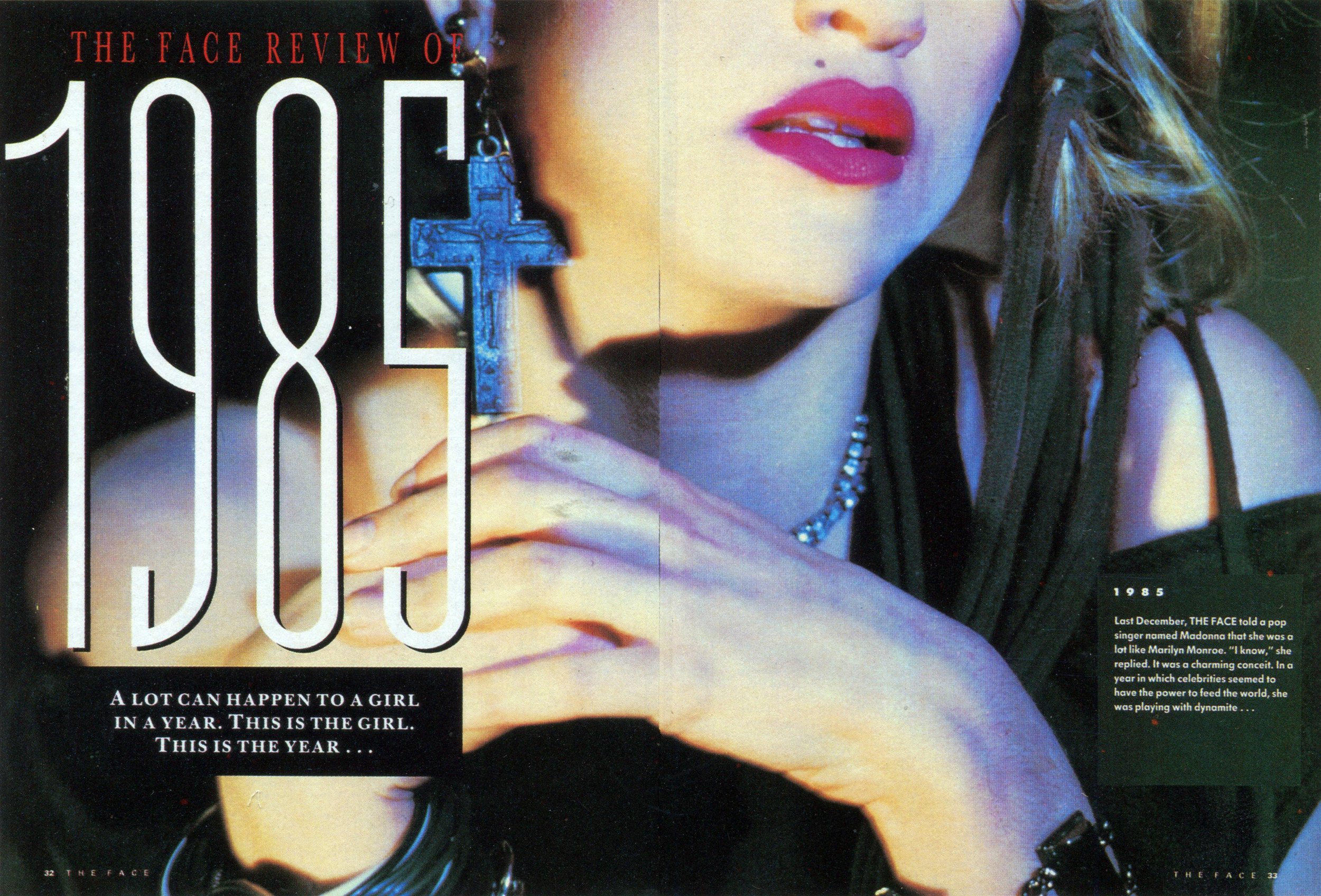

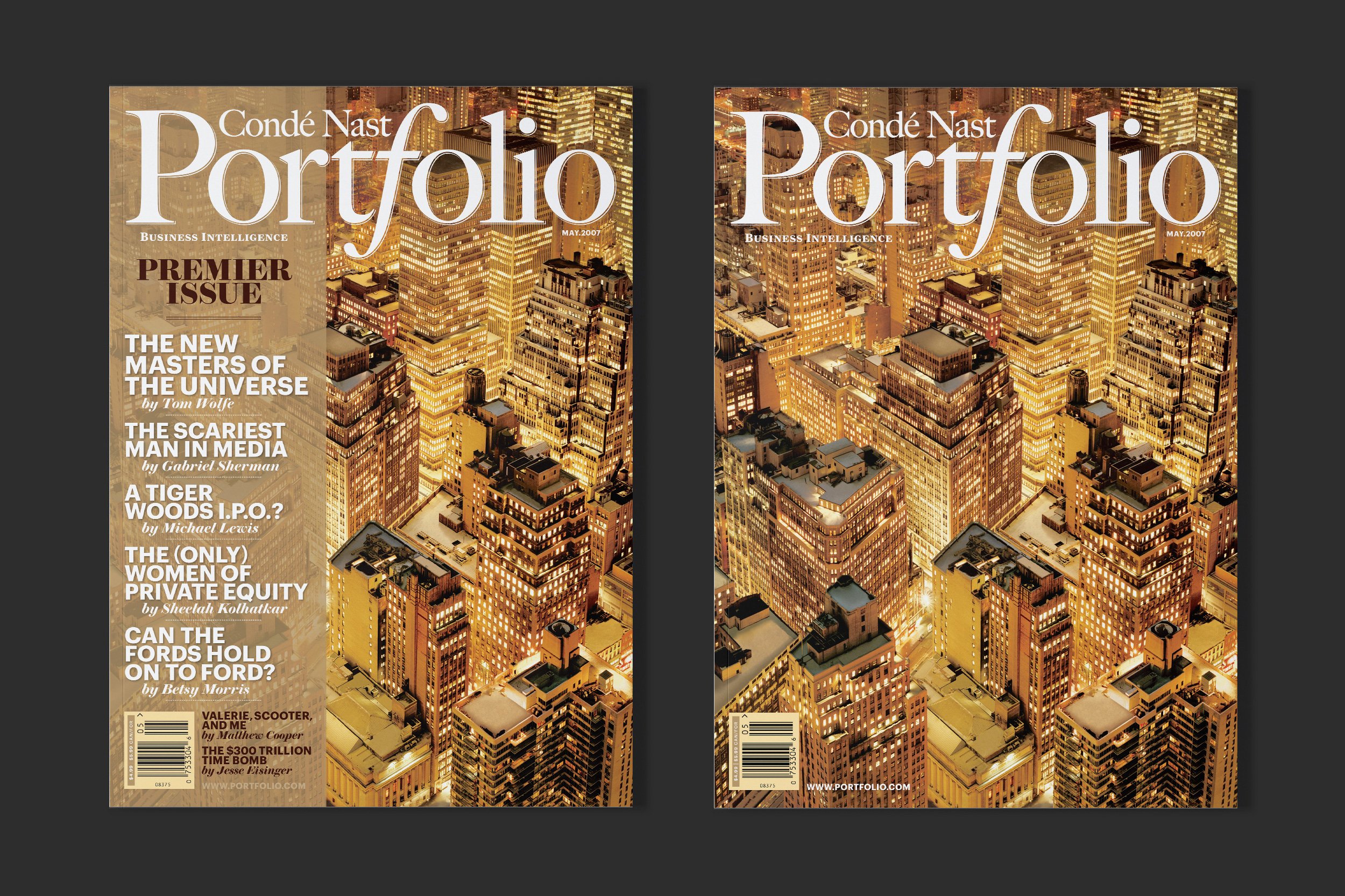

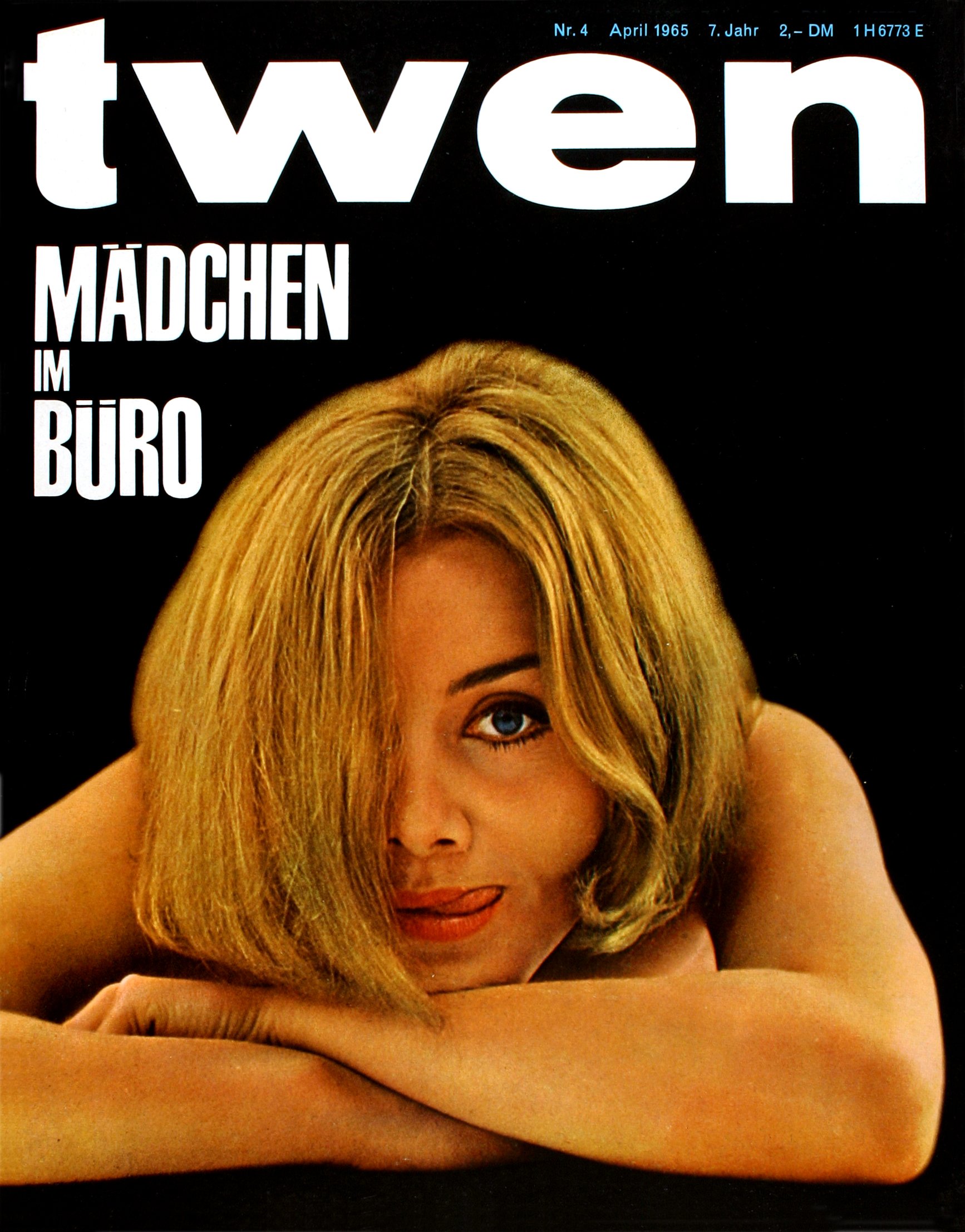

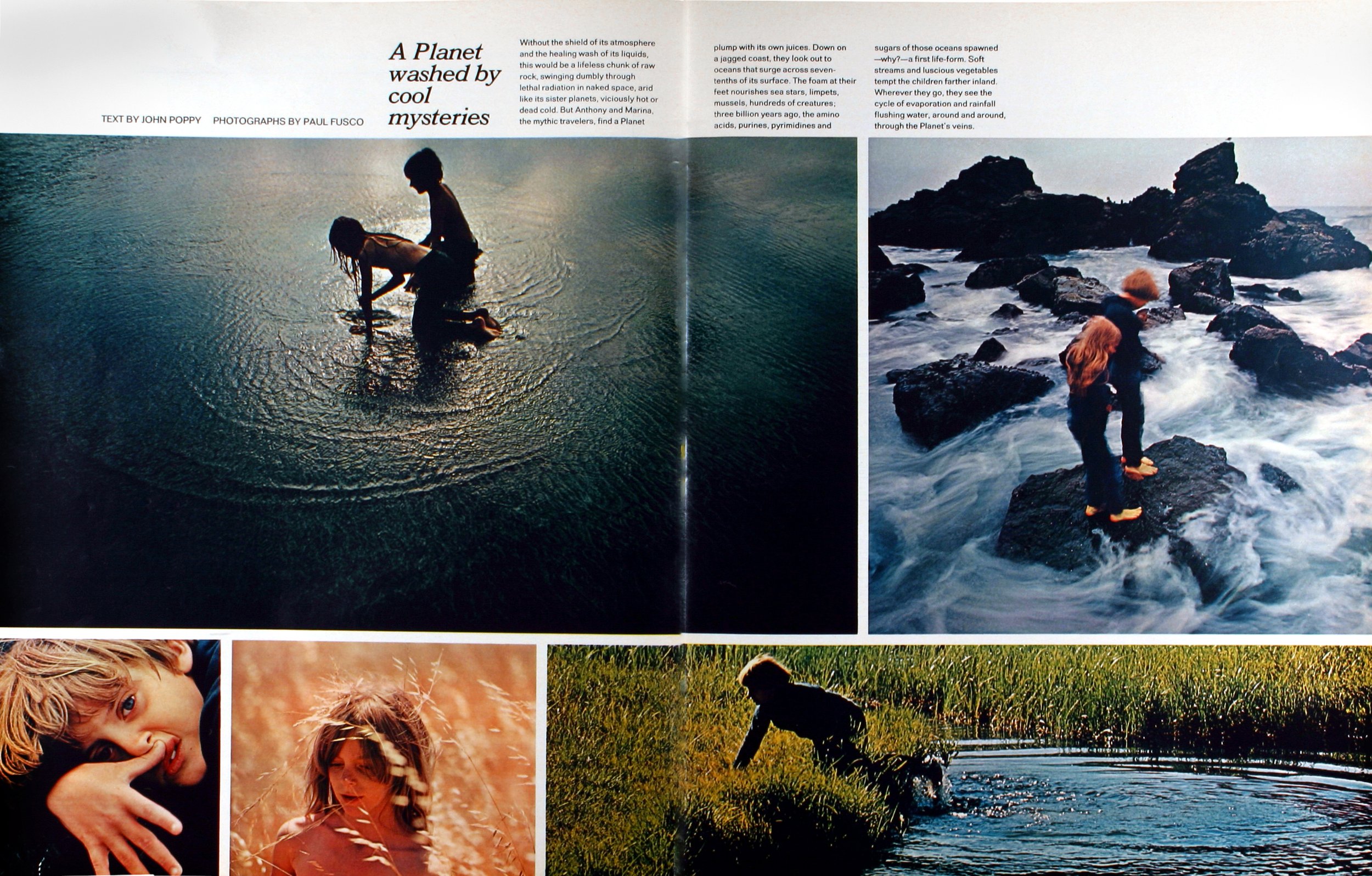

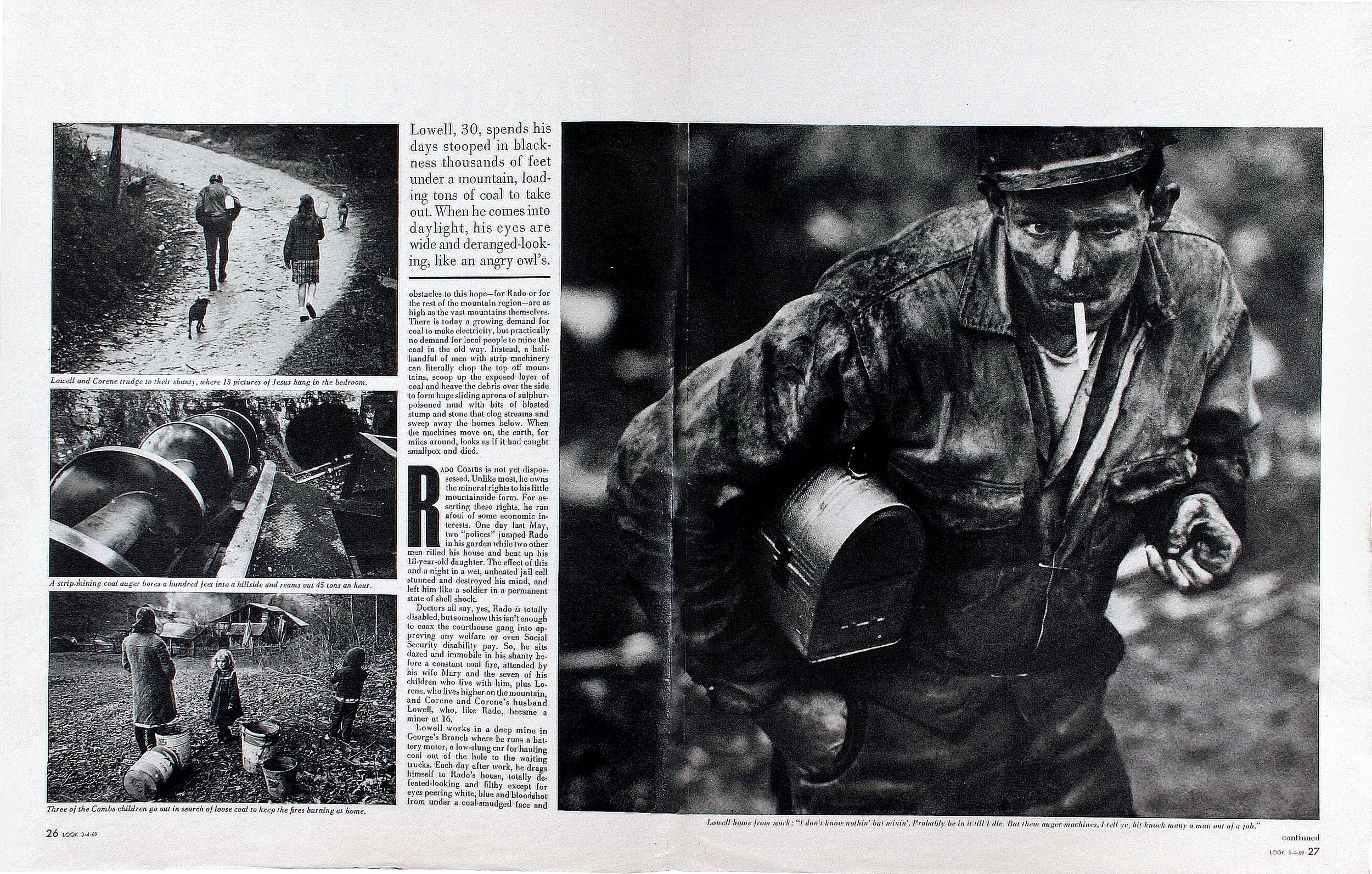

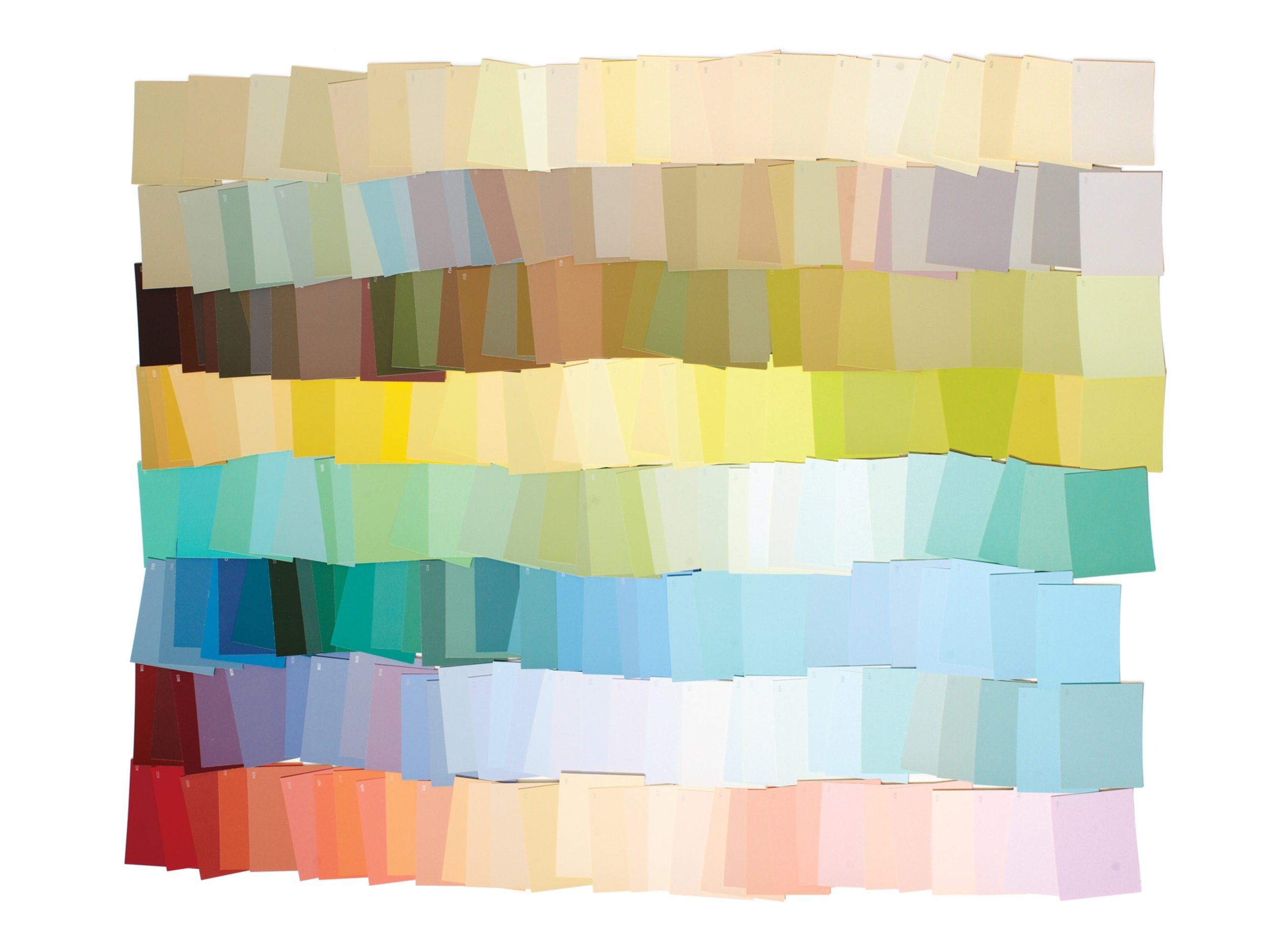

Debra Bishop: I know you put a lot of research and thought into your redesigns. You redesigned Wired in 2007. What was the mandate or the brief from your editor-in-chief at the time, Chris Anderson?

Scott Dadich: So Wired, at that point, was living in that lane that was fairly popular, that every issue could be a different idea. It could hold a different style. It could hold a different ethos. It could hold different typefaces, and color palettes, and design systems.

And Chris and I talked about this quite a bit—we both had pretty strong ambitions for what we wanted to do with it. I remember, though, being really influenced in an early interview with Chris by the “Sunflower” iMac. It was the WALL-E-looking white pod, and the chrome arm, and that articulating panel, which was so new and just such a revolutionary design.

And I compared it to the Bondi blue original iMac. And I said to Chris, “Wired, to me, is like the original iMac, that crazy color. It’s transparent plastic. You’ve never conceived of a computer doing the following things, let alone looking this way.” And that, to me, had been Wired up until that day.

And I said to Chris, “It’d be amazing if we could actually make an evolution of the magazine that felt more like the Sunflower iMac, that was reserved and hugely ambitious in its own right, but much leaner and then take a lot of the color out. And, actually, the only place where the color would live would be in the commissions, and the photography, and the illustrations, and not in these crazy full-bleed fluorescent...

Patrick Mitchell: A lot of people probably don’t remember the original Wired that John Plunkett was the art director of, but they introduced the just over-the-top, money-wasting idea of fifth-color interior signatures of metallics and fluorescent inks. Did that legacy at all influence what you were doing?

Scott Dadich: It definitely did. I was a huge fan. I remember also being at the University of Texas, as an engineering student, having $4 to my name, and trying to rub those nickels together to buy a copy of Wired—and a copy of Fast Company, you’ll be proud to know—at the Book People bookstore right there by campus.

And I loved that magazine. It was becoming clear though, I think, even then in 2006-2007 that the economics that permitted John, and Louis [Rosetto], and Jane [Metcalfe] to make that kind of magazine from a production standpoint, that was not going to be feasible forever.

Patrick Mitchell: You dabbled in a little metallic yourself.

Scott Dadich: We definitely had our moments. And Chris was really great to say, “It’s your budget. You want to go nuts for one month? Go nuts. But you got to trim your sails the next month. You’ve got one year to make it right.” So there was responsibility in places, but it was awfully fun to be able to do that and get the jealous calls from friends. Like, “How did you guys get to do that again?”

Debra Bishop: I read somewhere that the 1958 Erik Nitsche book, Dynamic America, was a big influence on the redesign.

Scott Dadich: Definitely. So Carl de Torres, an incredible designer—he started as an intern with us. And as Carl just wowed us every issue with all that he was able to do. Carl and I got into vintage books and hunting around, both on the web and in person, for great, legendary design books. And that one was really front and center for us and sat right, in the center of the newsroom as one of those bibles for us.

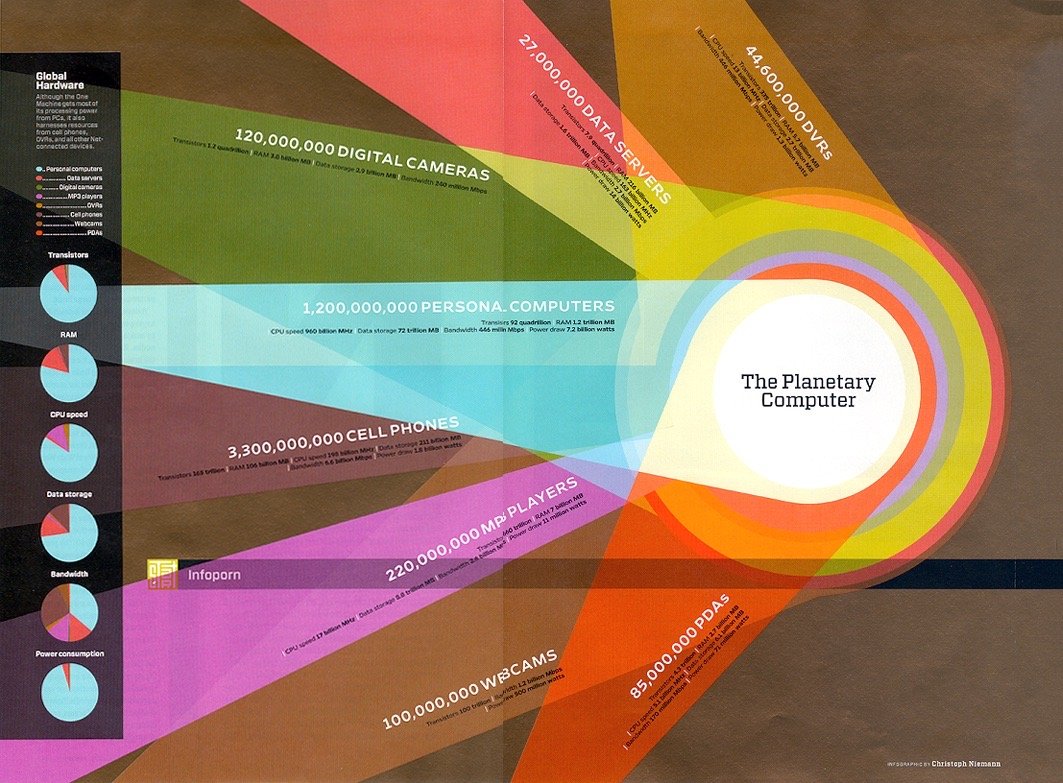

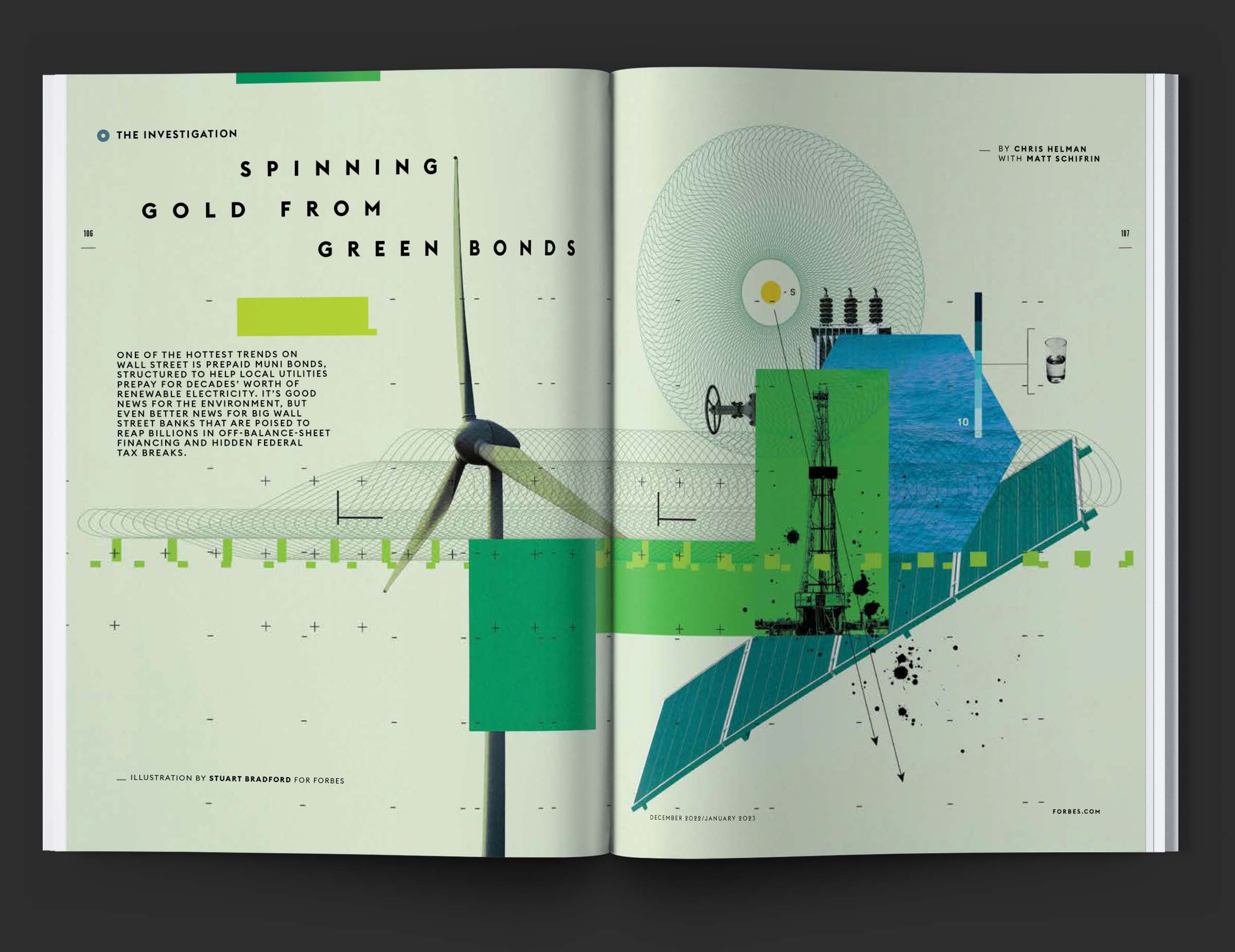

His work, and that book in particular, felt like it felt really important in that Eric in that work was able to visualize systems, and processes, and scientific phenomena that were impossible to visualize and make them clear, or understandable, or aspirational in ways that a lot of the work that we were trying to do at Wired—covering pretty abstract technologies or novel technologies.

Patrick Mitchell: I don’t want to get too in the weeds, but there was something specific about the grid of that book that inspired the Wired redesign. Can you talk a little bit about that without frightening off our non-designer friends?

Scott Dadich: How long have we got? No, I would say it spoke to—because of my love of math and engineering and that sort of rigor that had been put into my schooling around mechanical engineering in particular, that it just made sense to me. It just felt obvious in a lot of ways.

The other thing that it did—when John, and then Darren, even, had every available possibility to them, every choice they could possibly make in the universe from which photographer, which inks, which grid, which design system, and then even every feature well had a difference from feature to feature. It felt overwhelming to me. There was too much choice. And I wanted to put in some formality around constraint.

Obviously, we love constraints as designers. But it was one of those things that I just wanted to just press into the magazine foundationally, into the concrete that you could only do the following things with the following choices and the following typefaces.

Even to use Exchange as our body face, the engineering work that Jonathan put into that to perform because of its role for the Journal that we could flow copy and that—I remember there were copy editors and there were production folks at Wired whose only job was just to track copy and fix it. Just making the copy readable, comprehensible, attractive, that the textures would be fine.

I was like, Surely we can do better than that. And put those efforts into something more rewarding both for the reader and for the designers themselves. So let’s take all that labor out of this area and put it into this other area and see what we can do with that idea.

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah, the grid is a forgotten tool. It’s too bad. All it does is help you answer a lot of questions.

Scott Dadich: Yes. That is perfectly said.

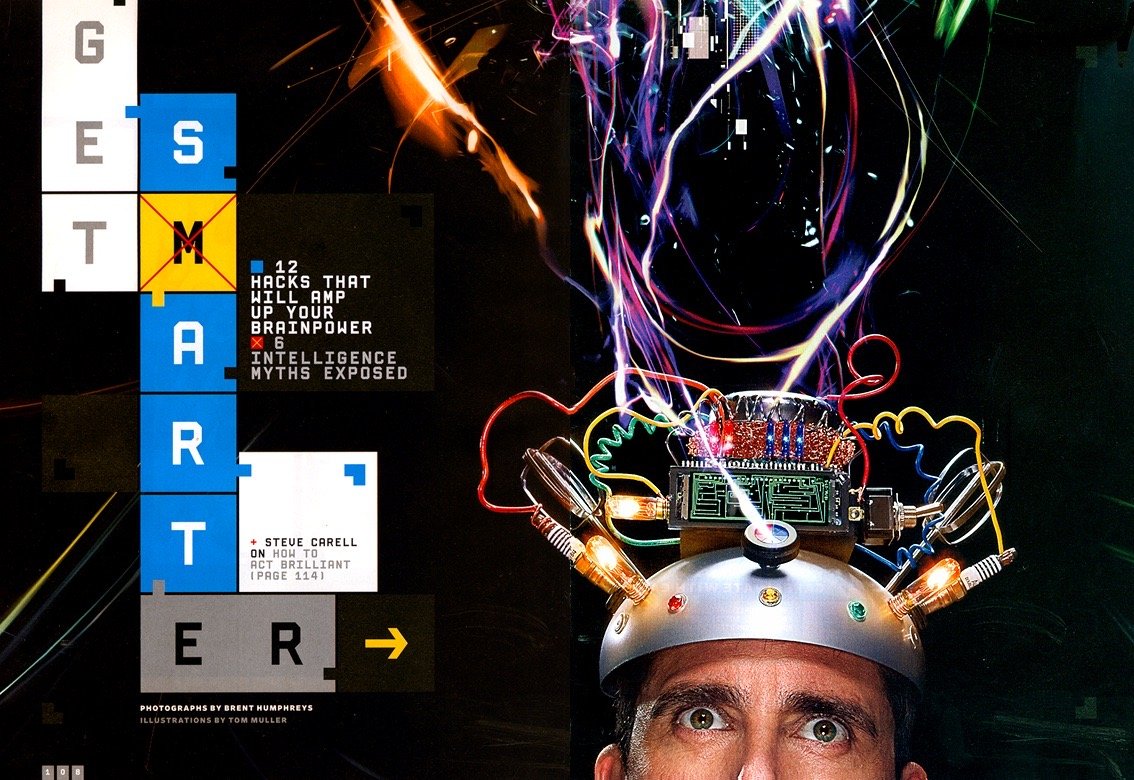

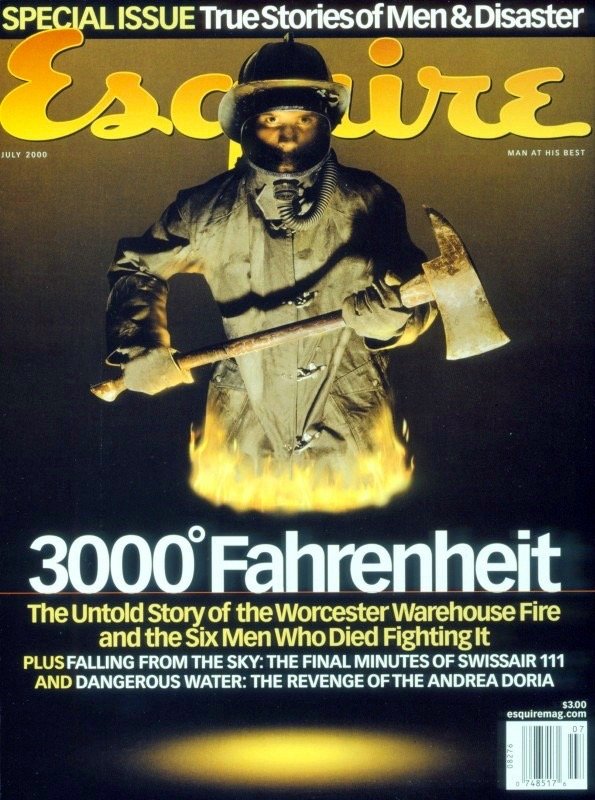

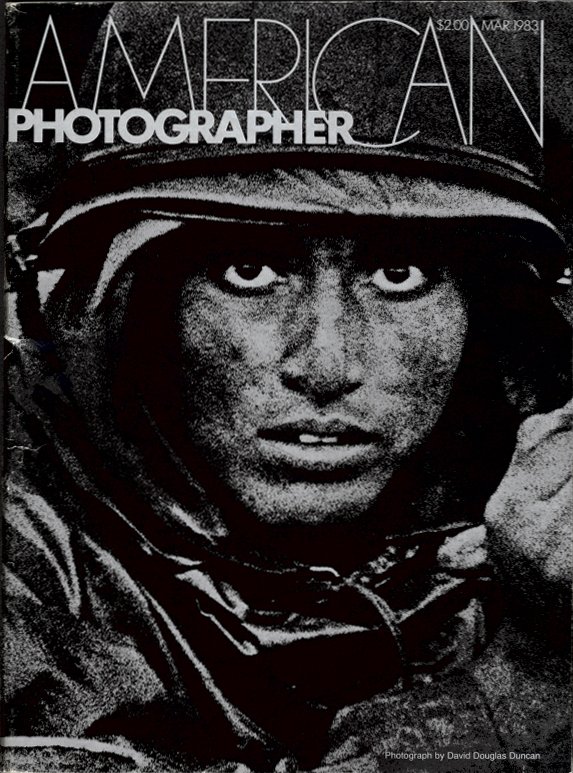

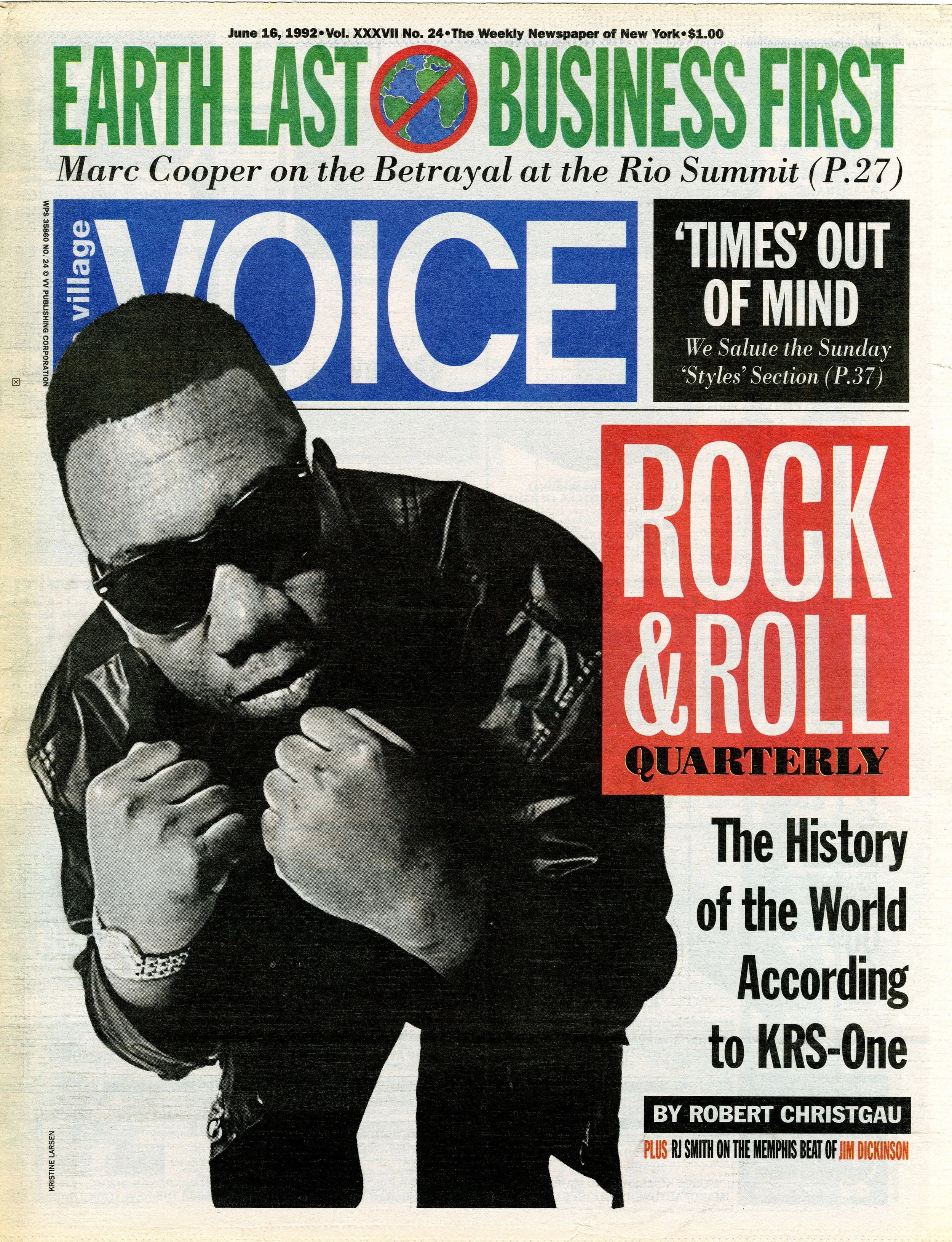

Patrick Mitchell: We’re going to circle back to Condé Nast Digital, but we want to jump right now into you being named editor in chief of Wired. I read your approach to that job was, “Let’s blow some shit up.”

Scott Dadich: I think that was the headline to my first editor’s letter, if I recall.

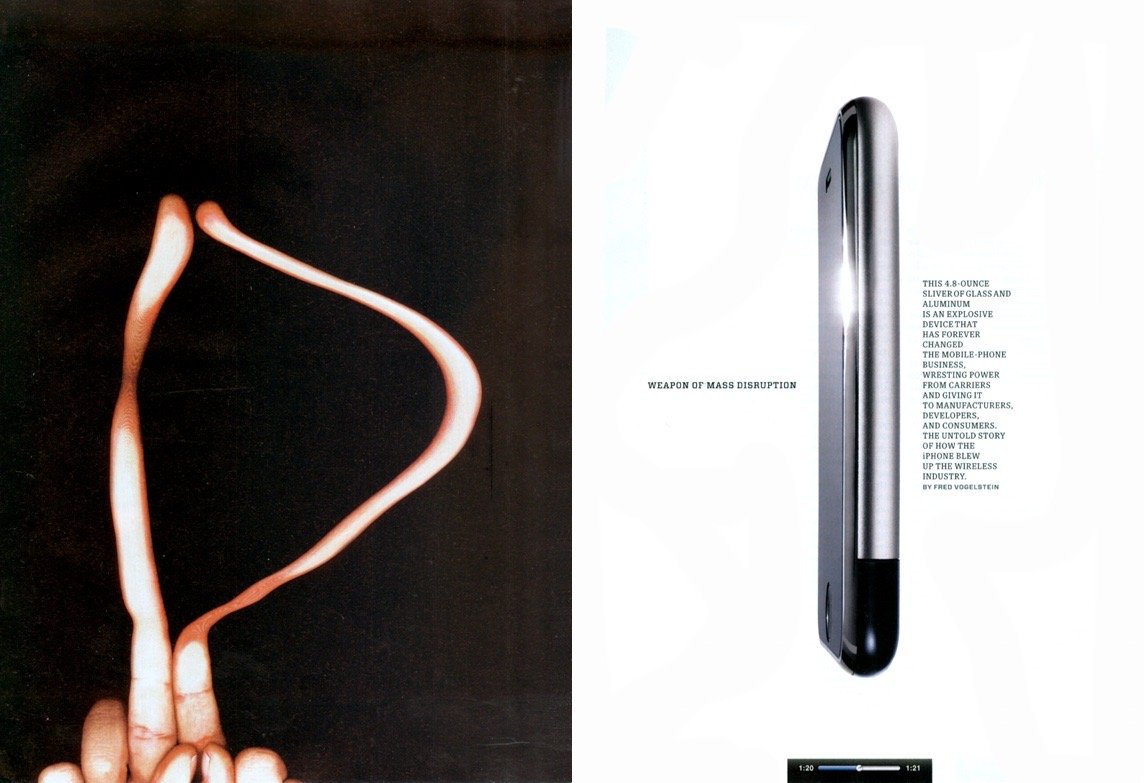

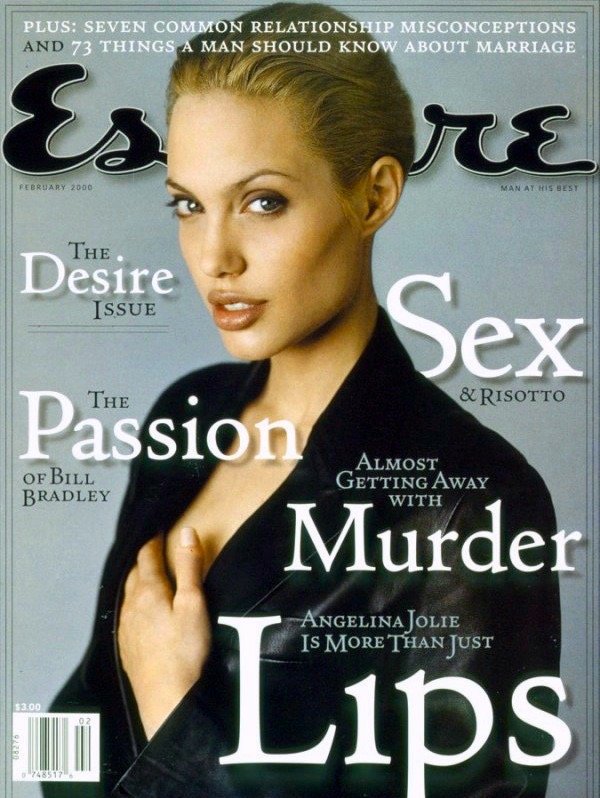

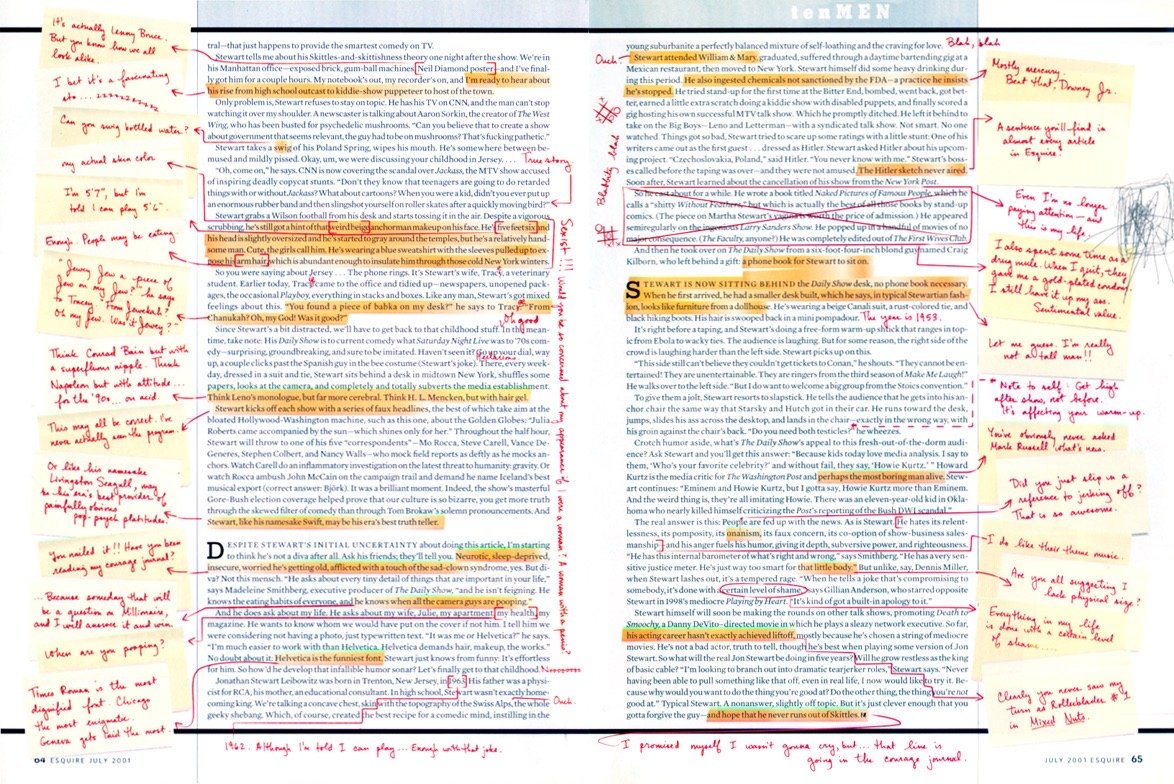

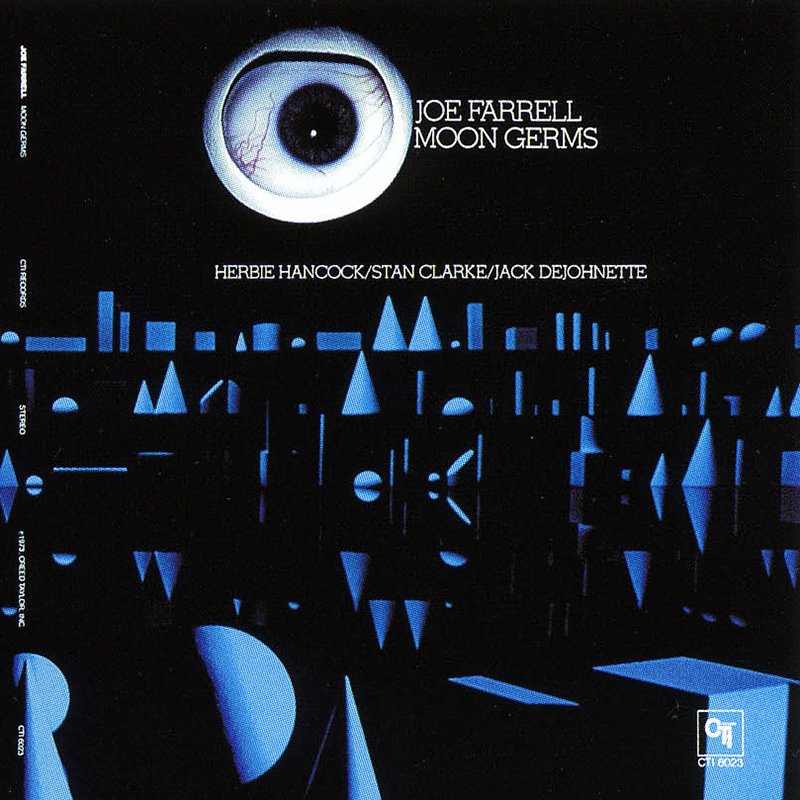

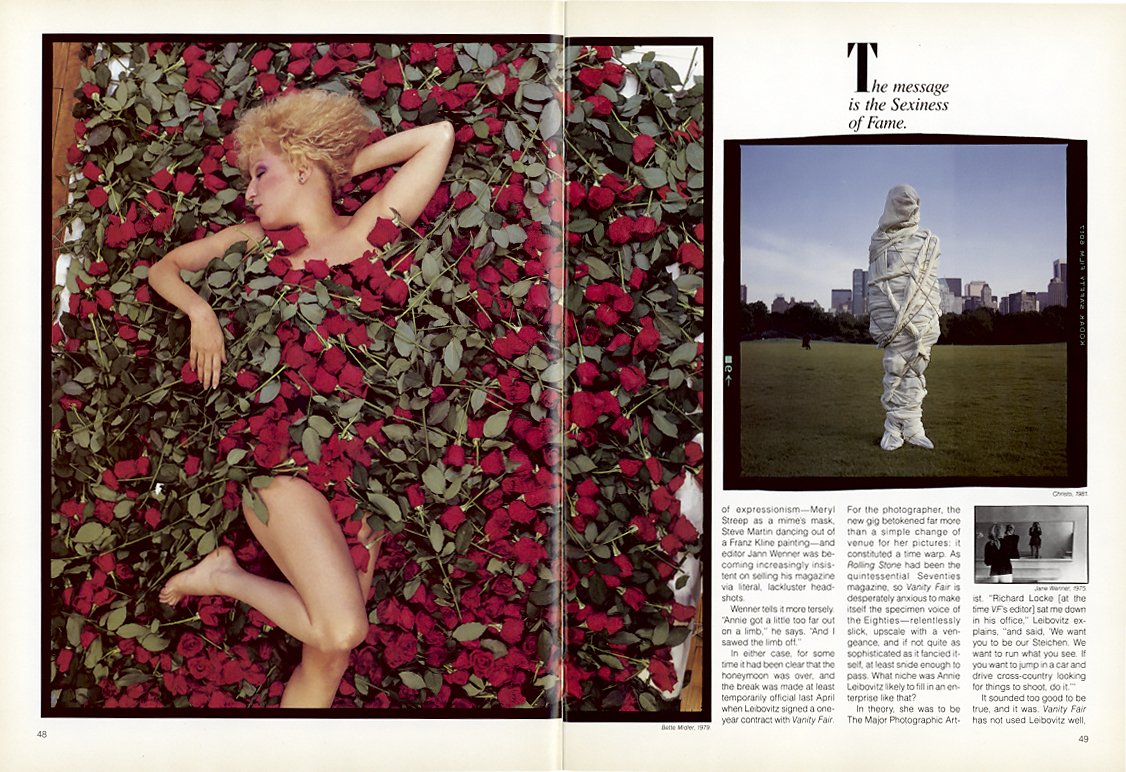

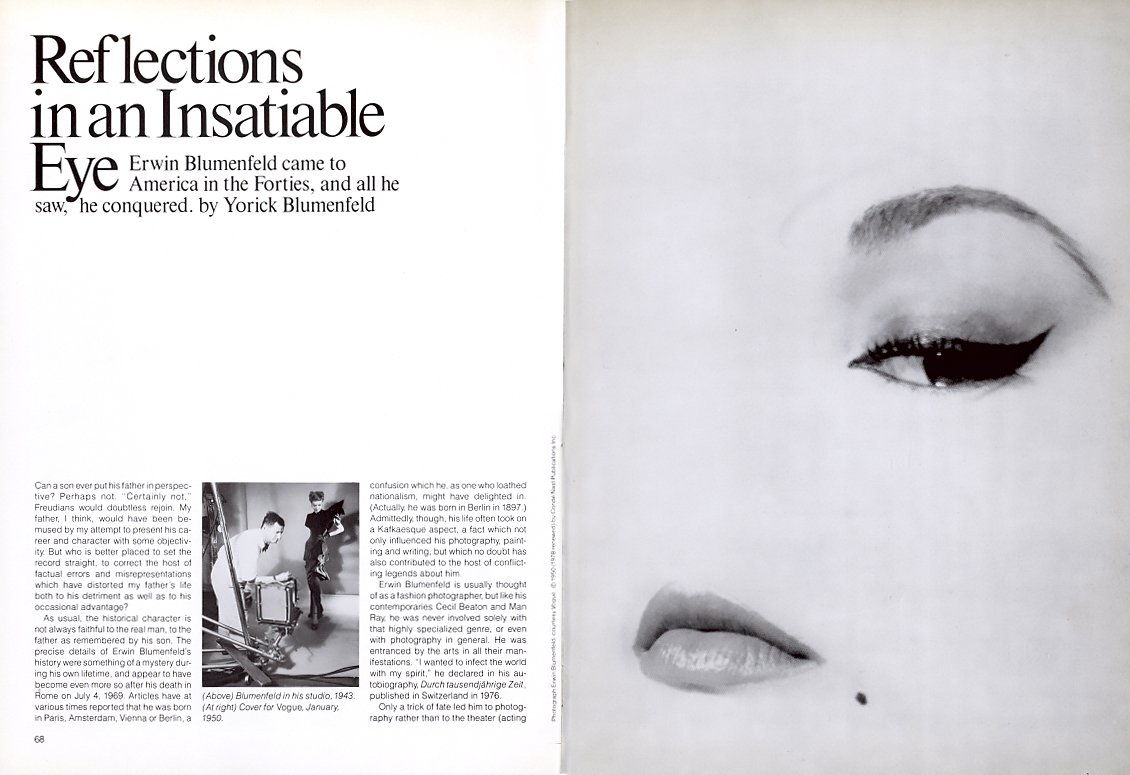

Mags on iPads. It really happened.

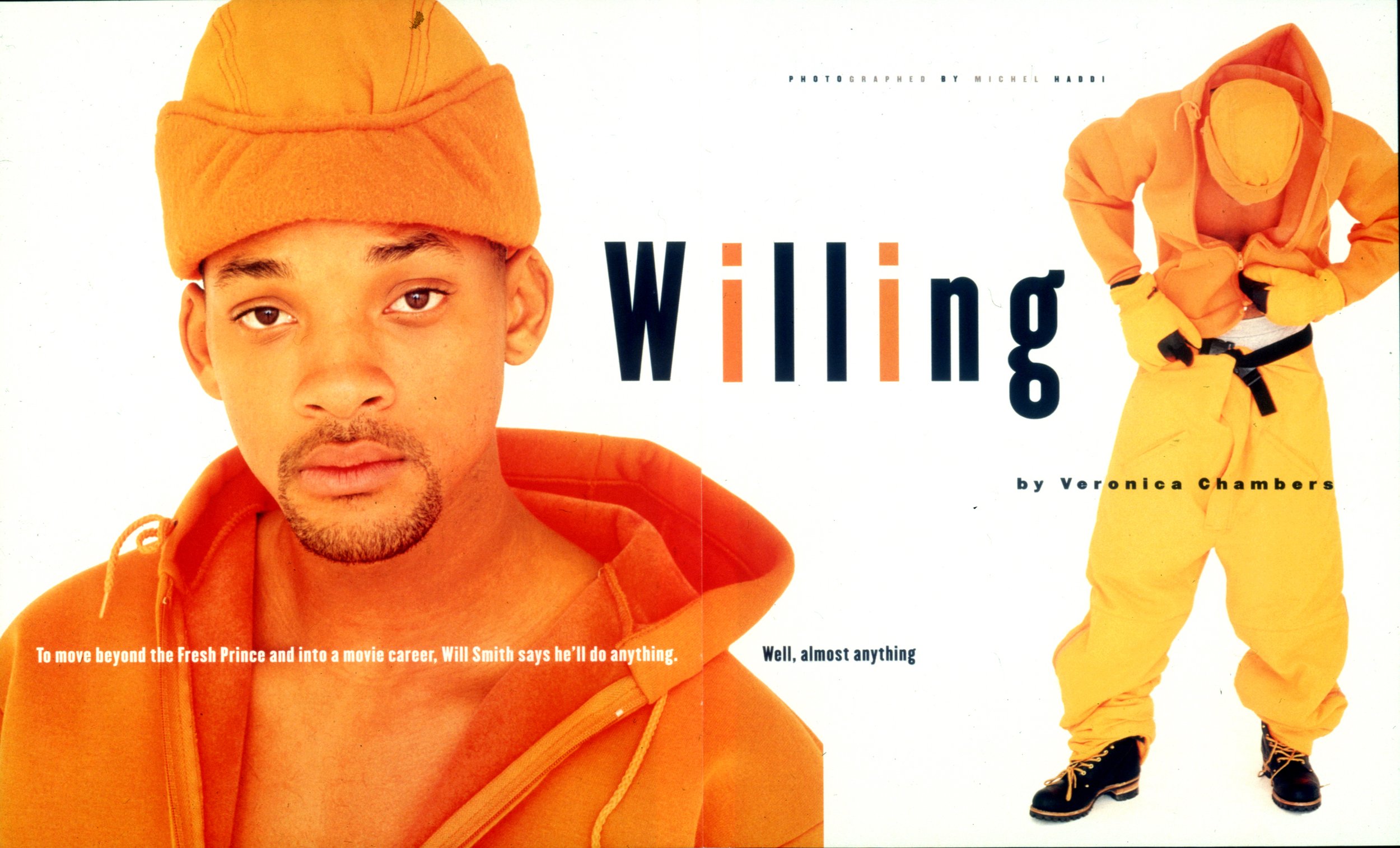

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah, welcome to the new world. Let’s talk about the, sadly, terribly-rare act of an art director becoming an editor. It seems just so, so big an idea, but it’s actually very logical. But how did those conversations get started?

Scott Dadich: I think I always had the ambition to become an editor-in-chief. And I probably even told Evan that I wanted to take his job from Texas Monthly on an occasion or two.

Debra Bishop: You had a plan. You had a plan for him.

Scott Dadich: Little did he know! So I felt early on at Texas Monthly that I got how that could happen. Evan taught me everything I knew about journalism. And my colleagues there, Pam Colloff, and John Spong, and those editors, Skip Hollandsworth, really schooled me in the ways of running a great magazine.

And then, at Wired, I really, I felt really familiar with Chris’s leadership in that Wired had a familiar purview and that it was a essentially a general interest magazine with one specific lens on it to innovation and technology in the way that Texas Monthly was a general interest magazine with a specific lens to it.

So I knew what Chris was doing and I admired it, but it wasn’t until I moved to New York and spent those two years working in Condé Nast corporate, working on digital strategy and, honestly, just getting to learn from David Remnick, Cindy Leive, Jim Nelson, Graydon Carter. To be sitting with them in their magazines every single day for two years was like getting my doctorate in becoming an EIC.

And I remember it was this Hurricane Sandy moment, and we had been displaced from our apartment, and my wife and I were sleeping on Wyatt Mitchell’s couch, and Tom Wallace gave me a ring one night. And said, “Chris just let me know that he’s going to be moving on. I’m running a search for a new editor in chief. Do you want to put your hat in the ring?”

And I was just blown away. And it just felt like it felt essential that I commit everything to it. And I had a conversation with Amy about it. And I said, “If this goes, that means you and I are moving to San Francisco.” And at the time, sleeping on Wyatt’s couch was like not exactly working. We were both up for a change.

So I went to work on a memo describing a vision that I felt was the right one for Wired and put my hat into the process. And probably a month later Tom called me to interview and we had that, and I sat with Si [Newhouse] and described to him what I wanted to do with Wired, and I think it was a day or so later, Tom asked me to his office and said, “You’re moving to San Francisco.”

Patrick Mitchell: You had the benefit, again, of the timing of where the magazine business was. It was just like, Something’s got to work. We can’t keep doing things the way we’ve been doing them.

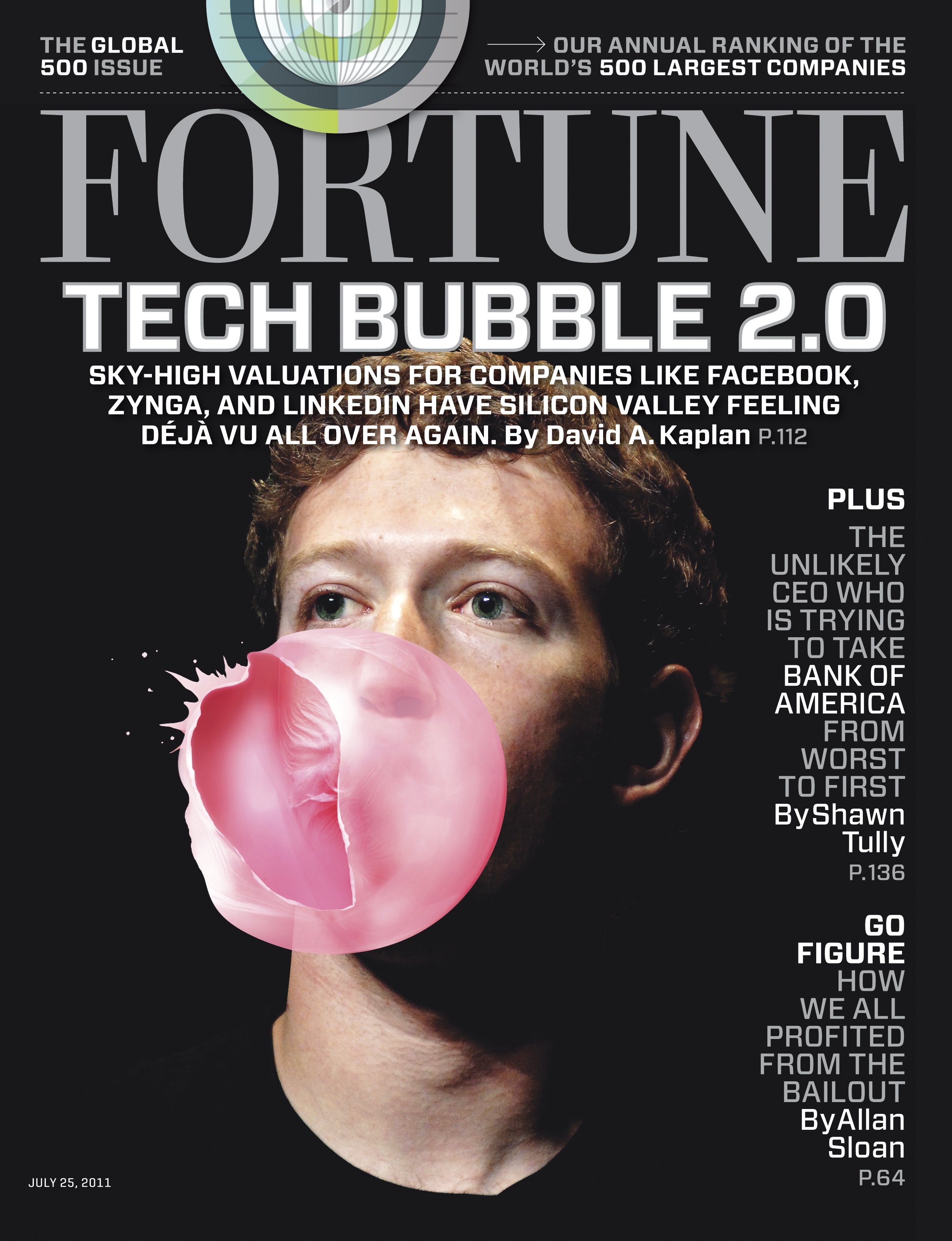

Scott Dadich: Part of the vision I tried to paint was—so Condé Nast did not own Wired.com. When they acquired Wired from Jane and Louis, its founders, they did not buy Wired.com. It was sitting at Lycos. And it was literally on a machine sitting in a server closet in Baltimore. And I remember when we got it back, it was a big moment.

And we knew that there had to be a big part of the business that would live through Wired.com, and all of the attendant, and corollary, work that needed to come out of the digital channels—a social business, a video business. And so part of the mission, part of what I tried to describe to Tom and to Si was that I wanted to reunite those newsrooms back from their earliest days and bring the original vision of Wired back together. That literally people had to sit together.

And because of the premise that Wired.com was a different group—we called it the “Berlin Hall.” It was the same floor, but different key cards, different offices, different editors-in-chief, different coverage mandates. And it was really about pushing everything together from, literally, the newsroom, to the architecture of the floor, to the systems, to the editorial charter and the kinds of stories that we wanted to tell.

Debra Bishop: I think this is one of the biggest mistakes that magazines made early on, was not combining digital with the print, and making it one team and deploying the same content.

Scott Dadich: We felt the frustration firsthand. I remembered very specifically that the agreement between Wired.com and Wired magazine at that time was that we would take the magazine, print it out and put it in a binder, put it on a couple of DVD-roms, and literally walk it across the hall and say, “Here’s the magazine. Put it on the internet.” And it was not fun for anybody in that scenario. So the pain of that experience was certainly a driver in our thinking to reunite everything.

Debra Bishop: Talk about the transition, though. How did your transition from creative director and then being editor-in-chief go over with the Wired team? How did that go?

Scott Dadich: I was so happy to go back because I loved that crew. I loved my colleagues. And in the two years that I wasn’t there a couple of new colleagues had joined that I had just heard legend of. A woman named Caitlin Roper had joined, and Rob Capps. And it was a moment where I just felt really comfortable and excited.

Obviously there were points of friction where some folks had raised their hands for the same job and because I got the nod, there were changes that needed to be made. And some people chose to leave and that I think is a fairly standard moment in a magazine’s life cycle when it is going to evolve and new people bring their vision to the work.

But I got nothing but support from almost everybody there. And a real, “Let’s make this work.” And wherever you’ve got deficiencies—and I have plenty of deficiencies—people would really step in and say, “I got you on that. I can cover that if you can think about this over here.” So it really was a team effort from day one.

Debra Bishop: And on a personal level, as a designer, did you enjoy that move up? Was it a balancing act between letting go of visuals and letting someone else take over?

Scott Dadich: It was. I think one of the challenges I faced in that first year was because of the pre-existing relationships that I had with so many of my colleagues, and the context in which they knew me, and the reasons they’d come by my desk tended to do with a creative approach or a design approach rather than the editorial decision that needed to get made.

So I think it was when Billy Sorrentino took over as creative director that I really felt like I had a partner there. And I could see that decision-making, and I could work with him as a true collaborator and partner because I knew what it felt like to be treated like a partner by Chris or by Evan.

And I’d seen it at Condé Nast. I’d seen the relationships that were working well and those that weren’t. And so I had a bit of a model that I wanted to pursue. And as we had this sort of explosion in responsibilities in video, in social, in retail, in digital, in product, that we had to think about, it just became a necessity that it would be a team approach to leadership.

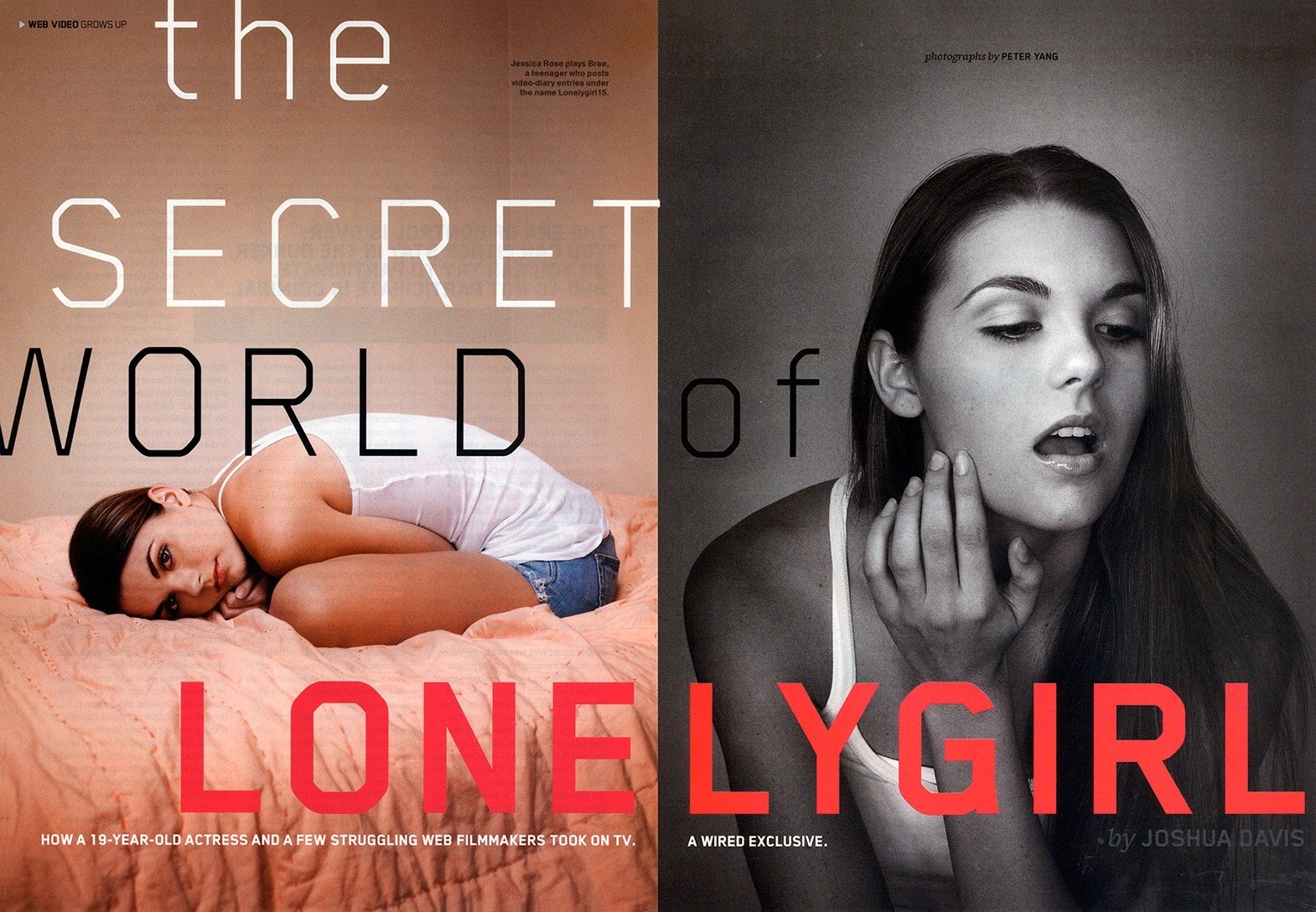

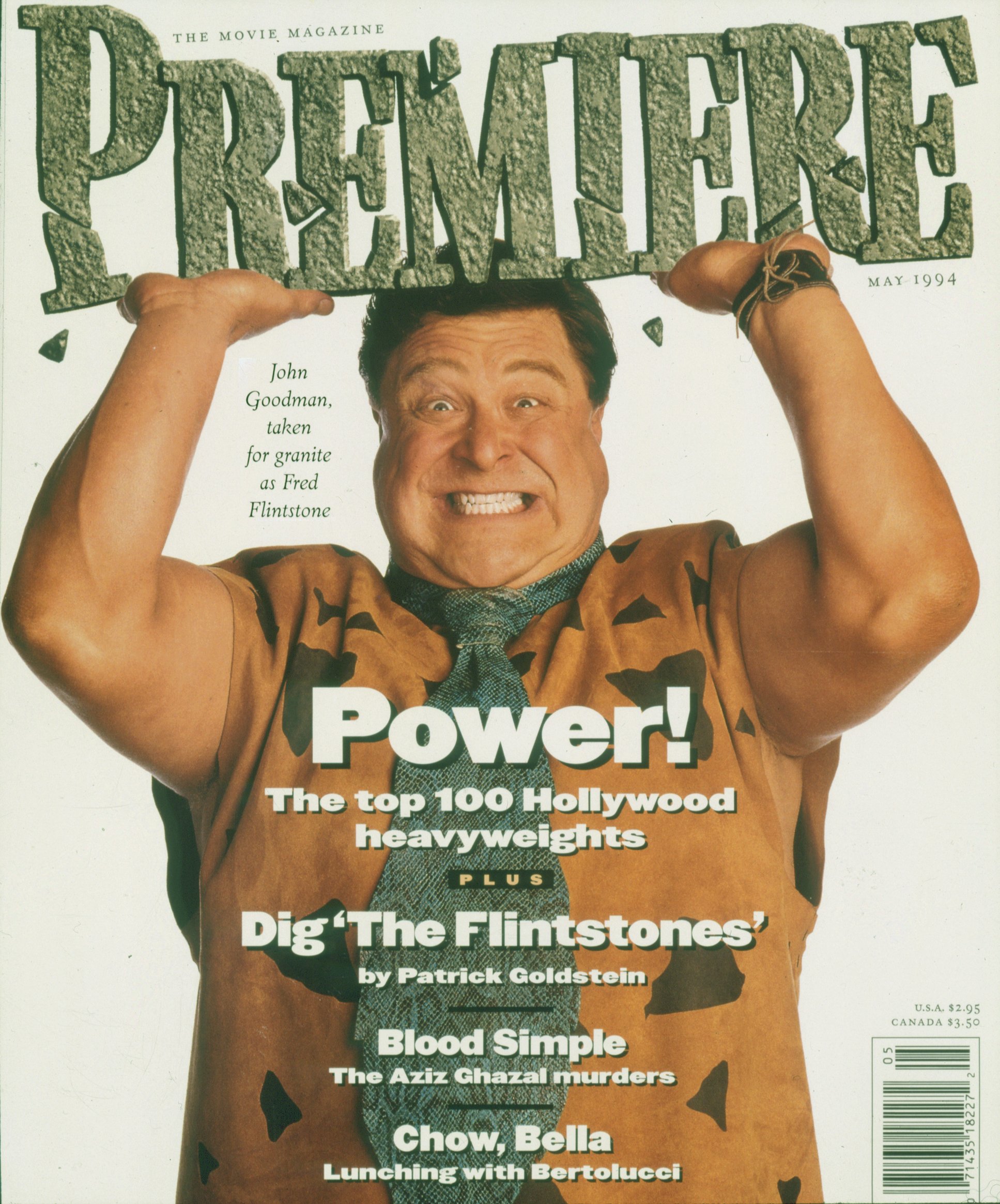

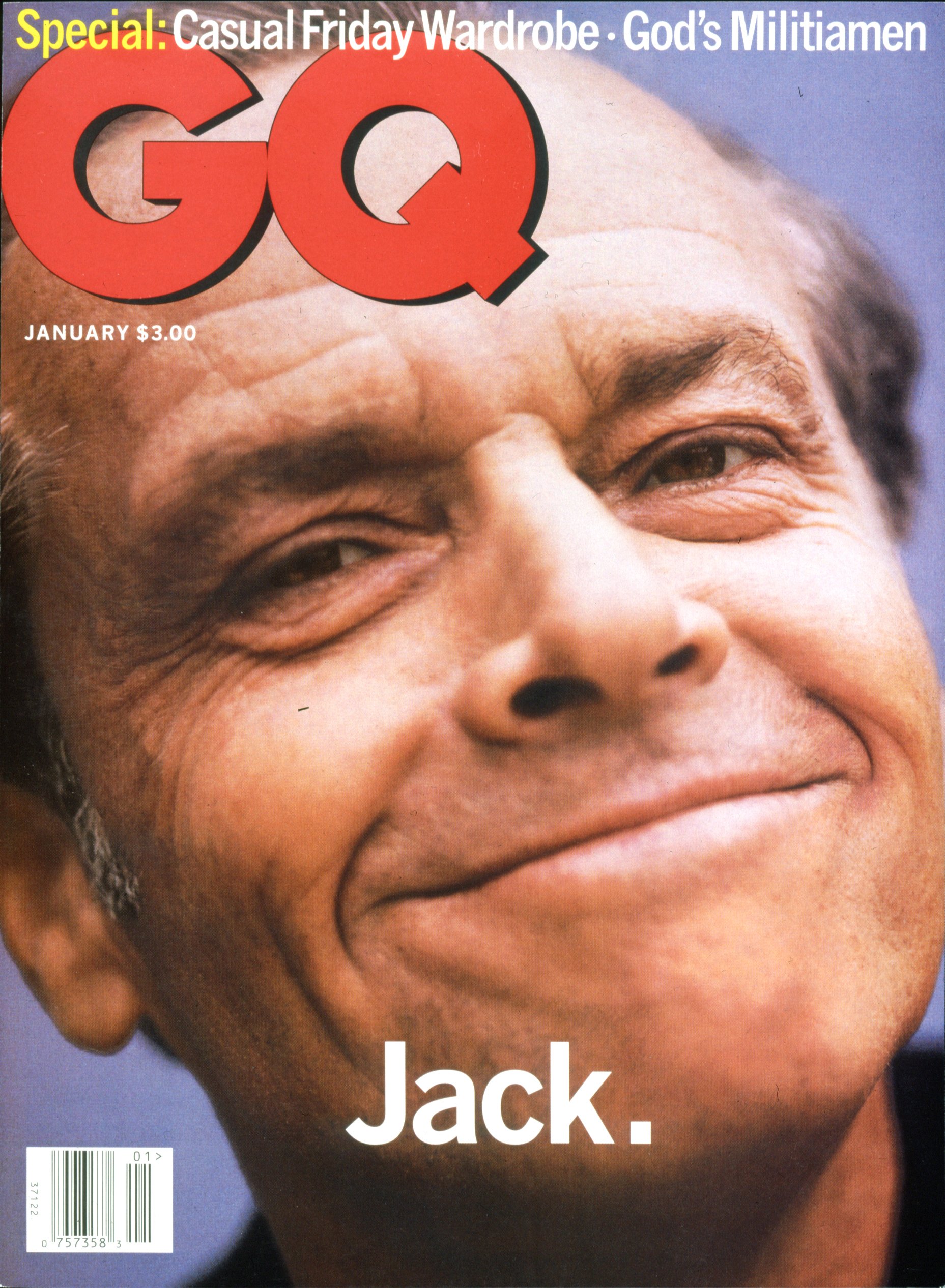

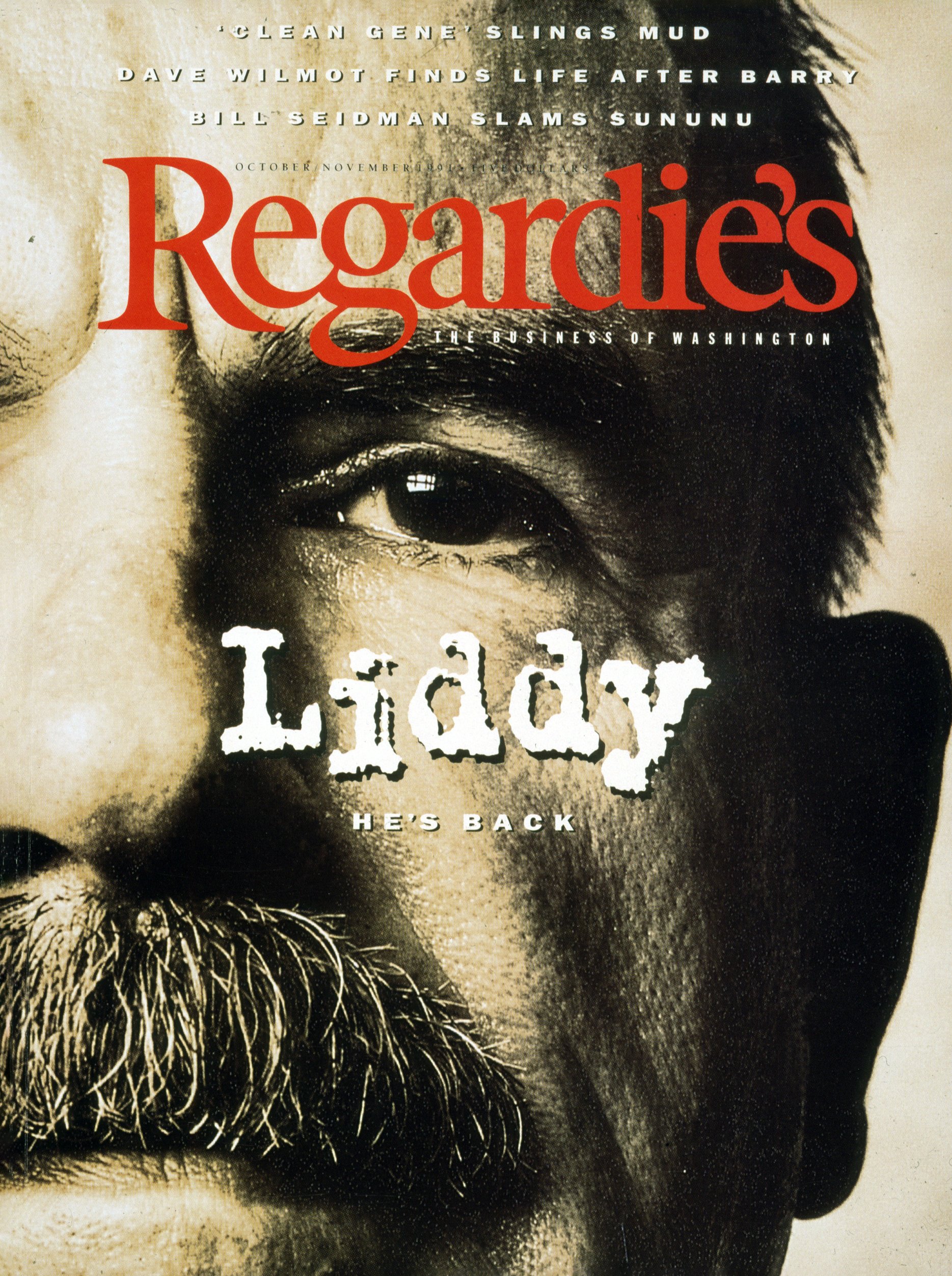

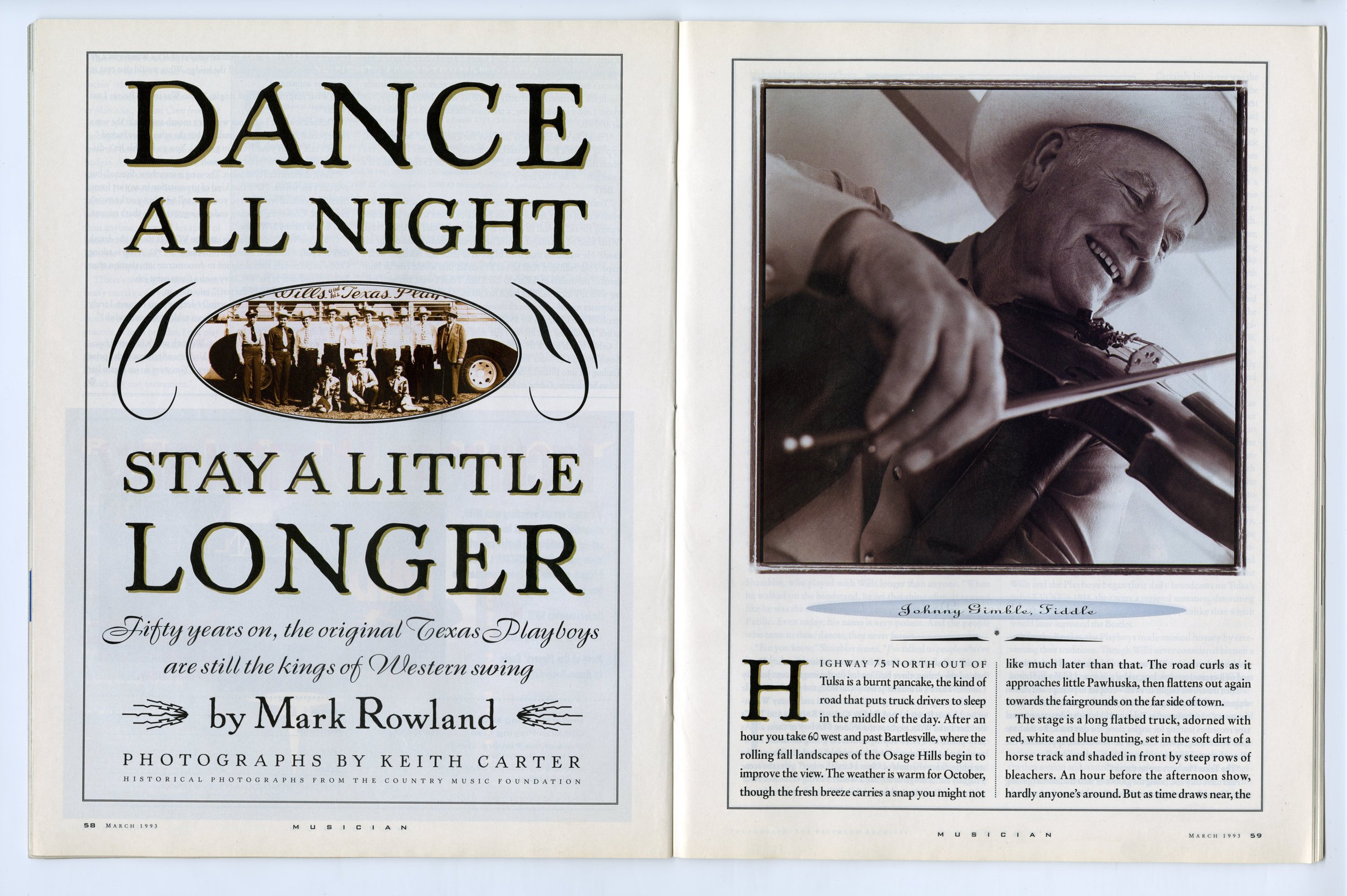

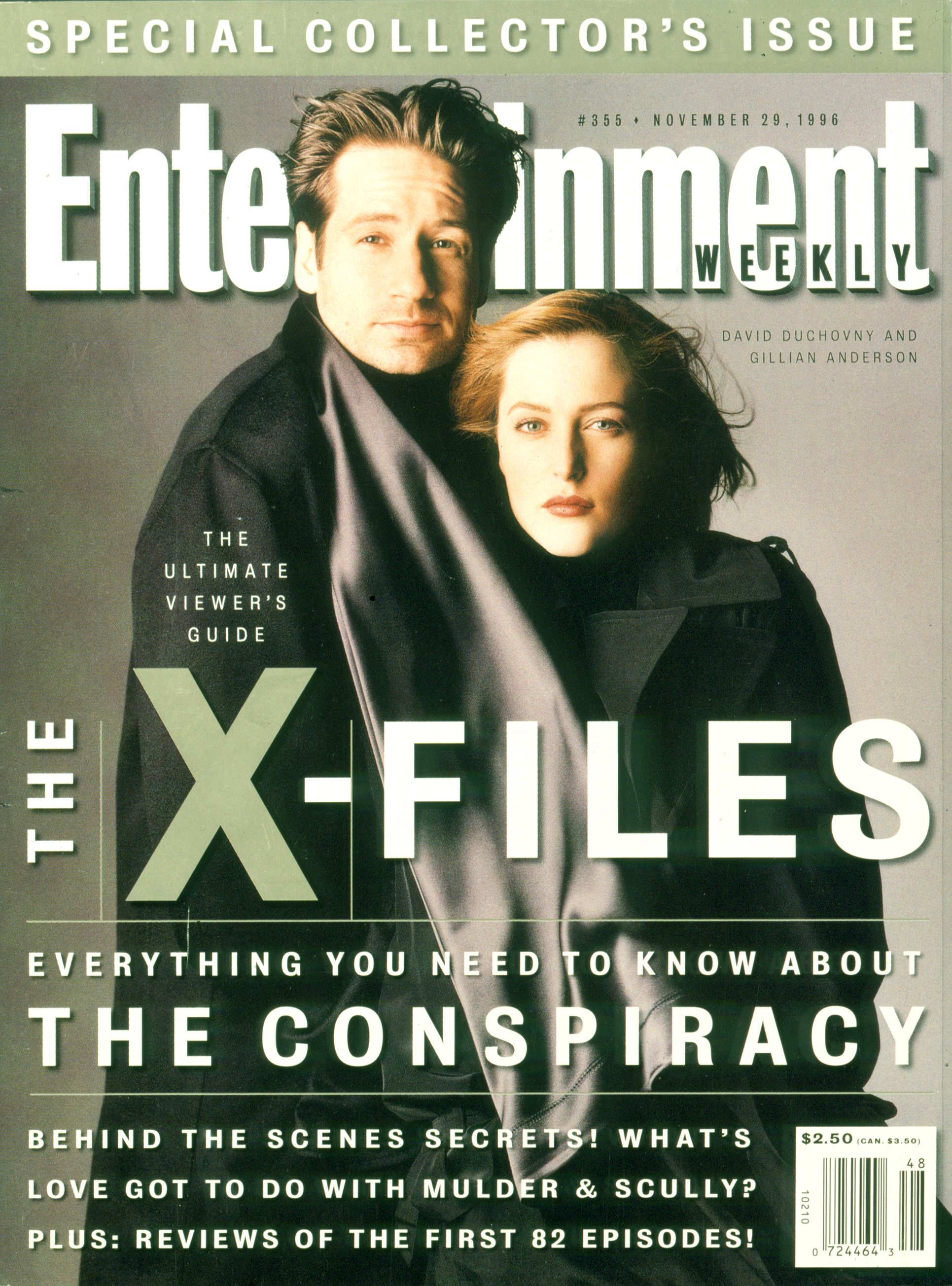

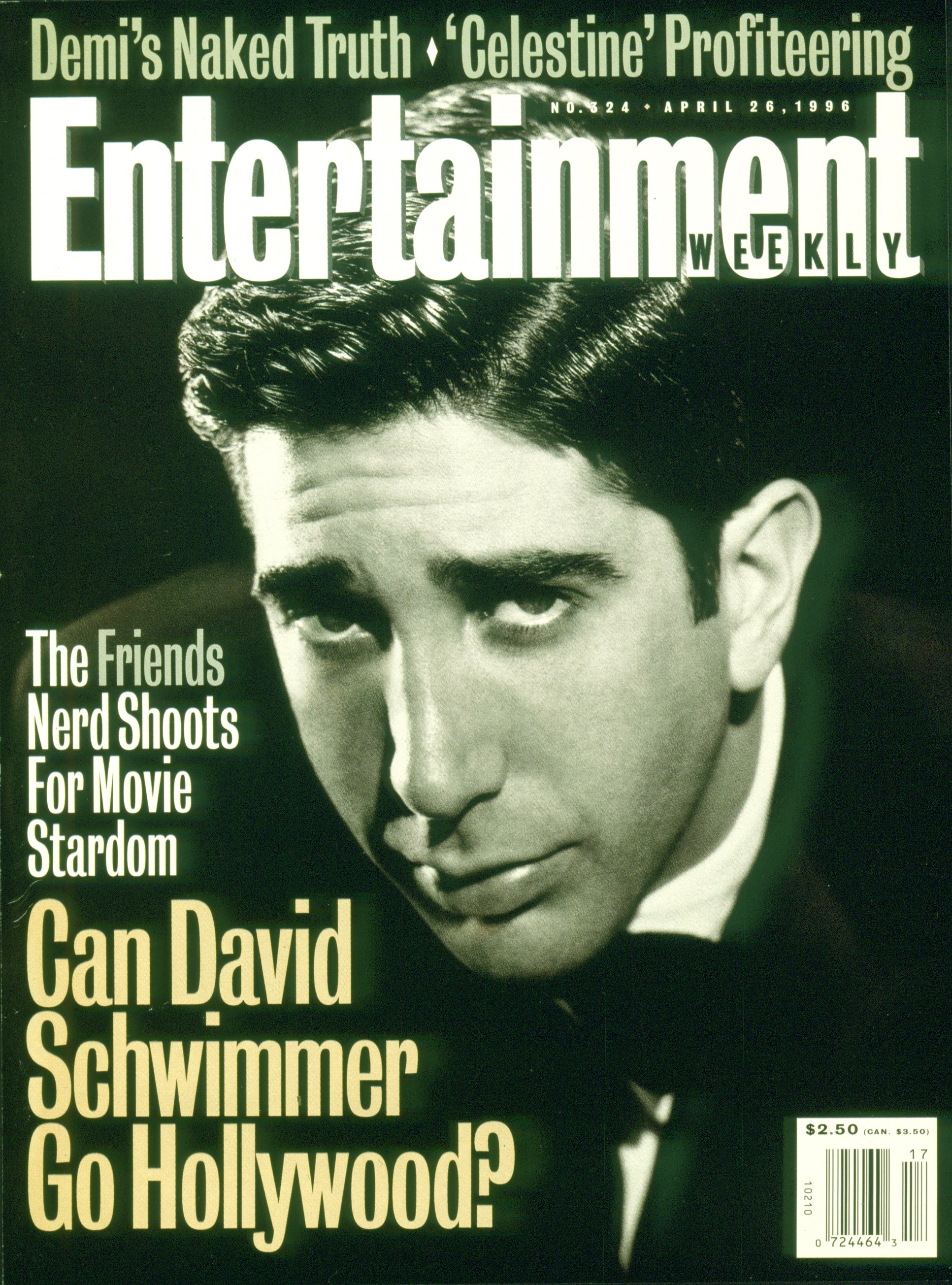

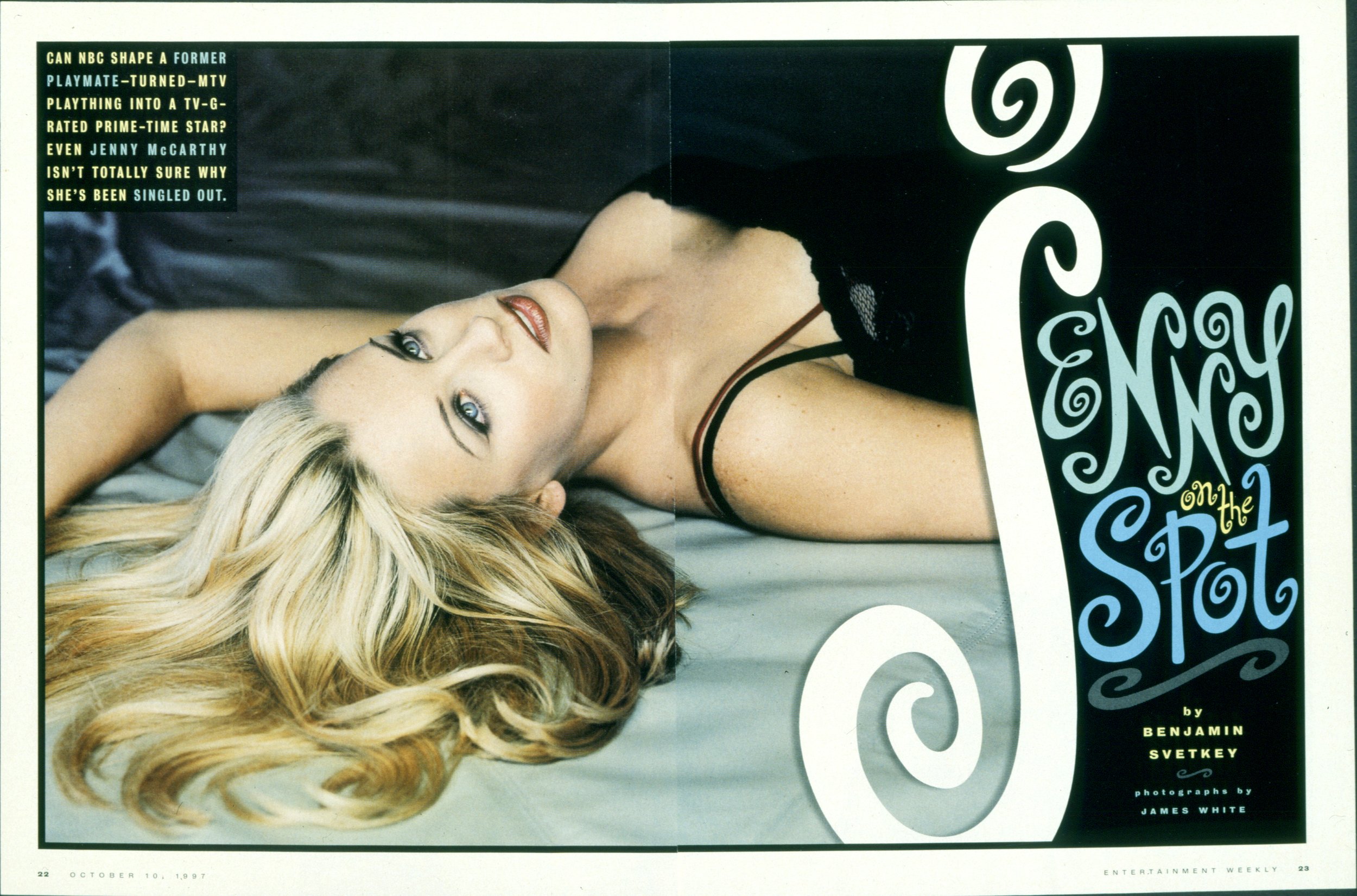

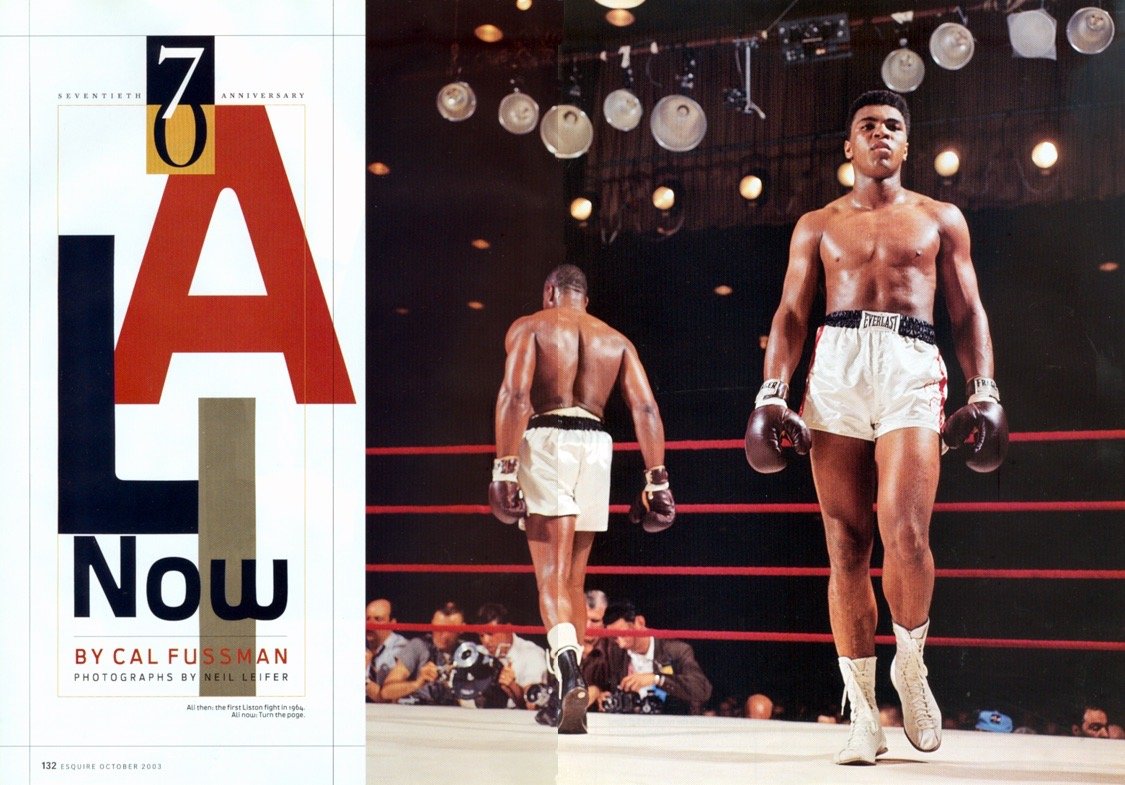

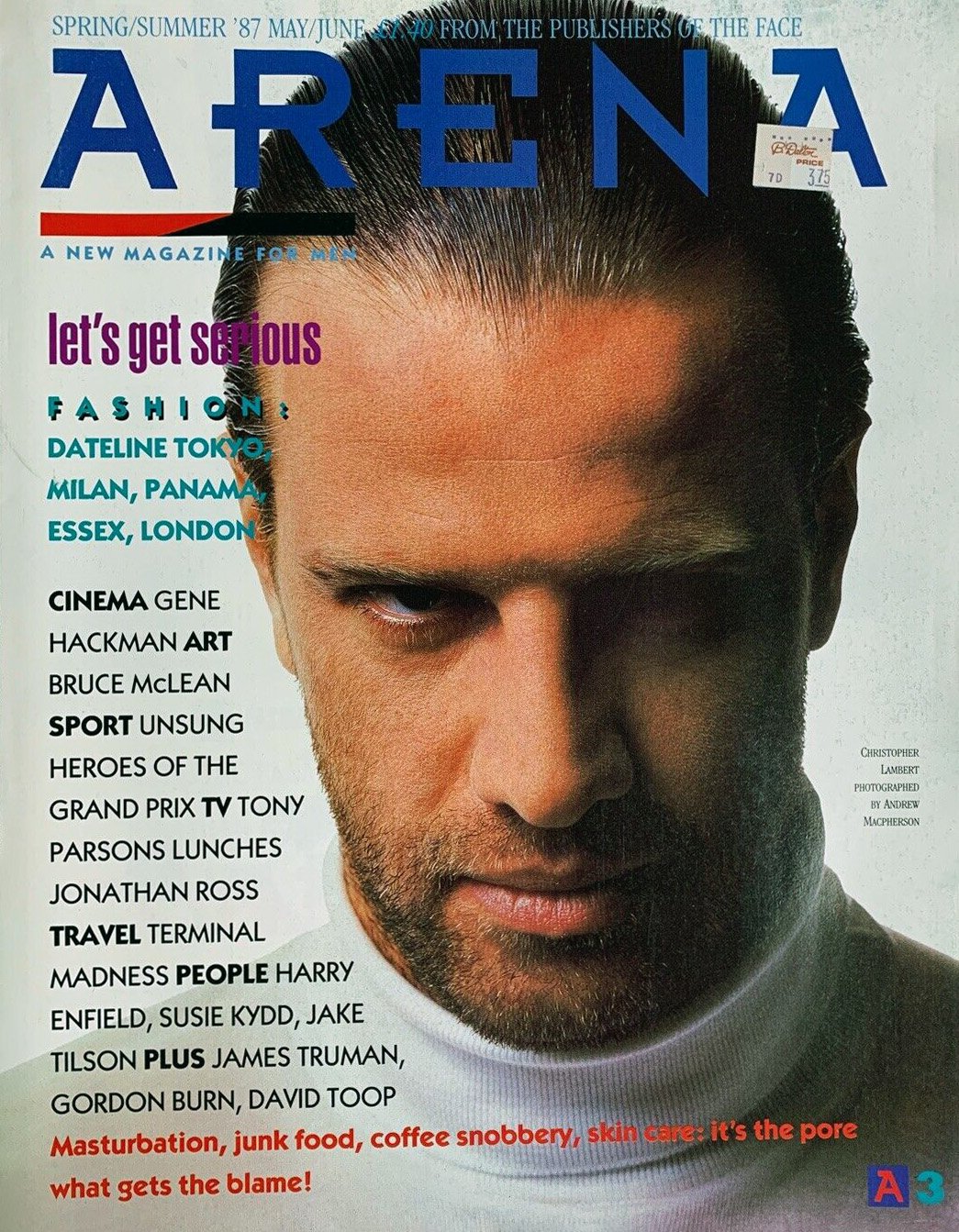

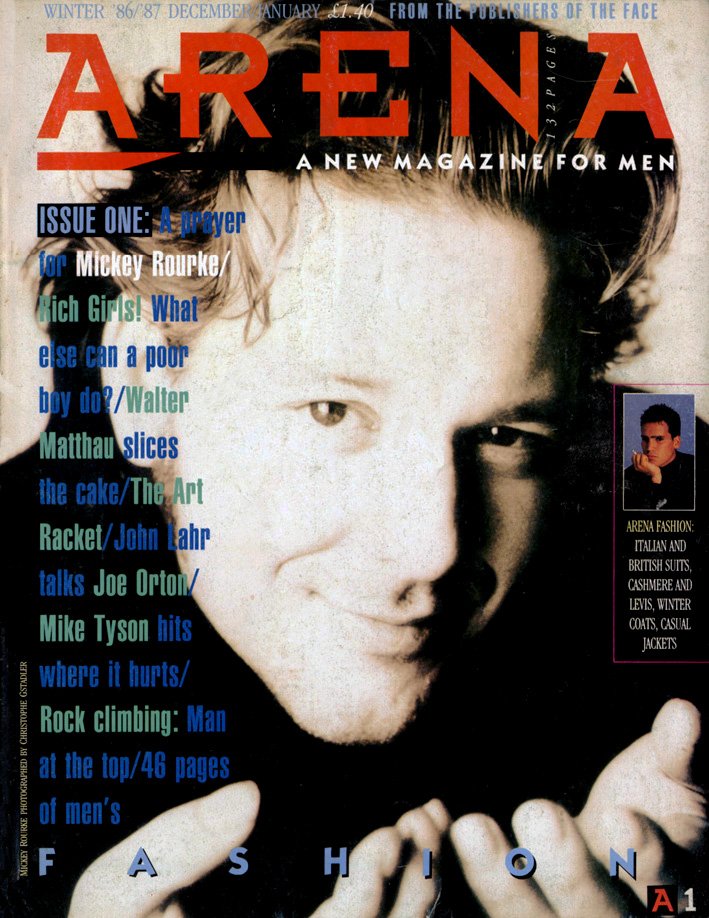

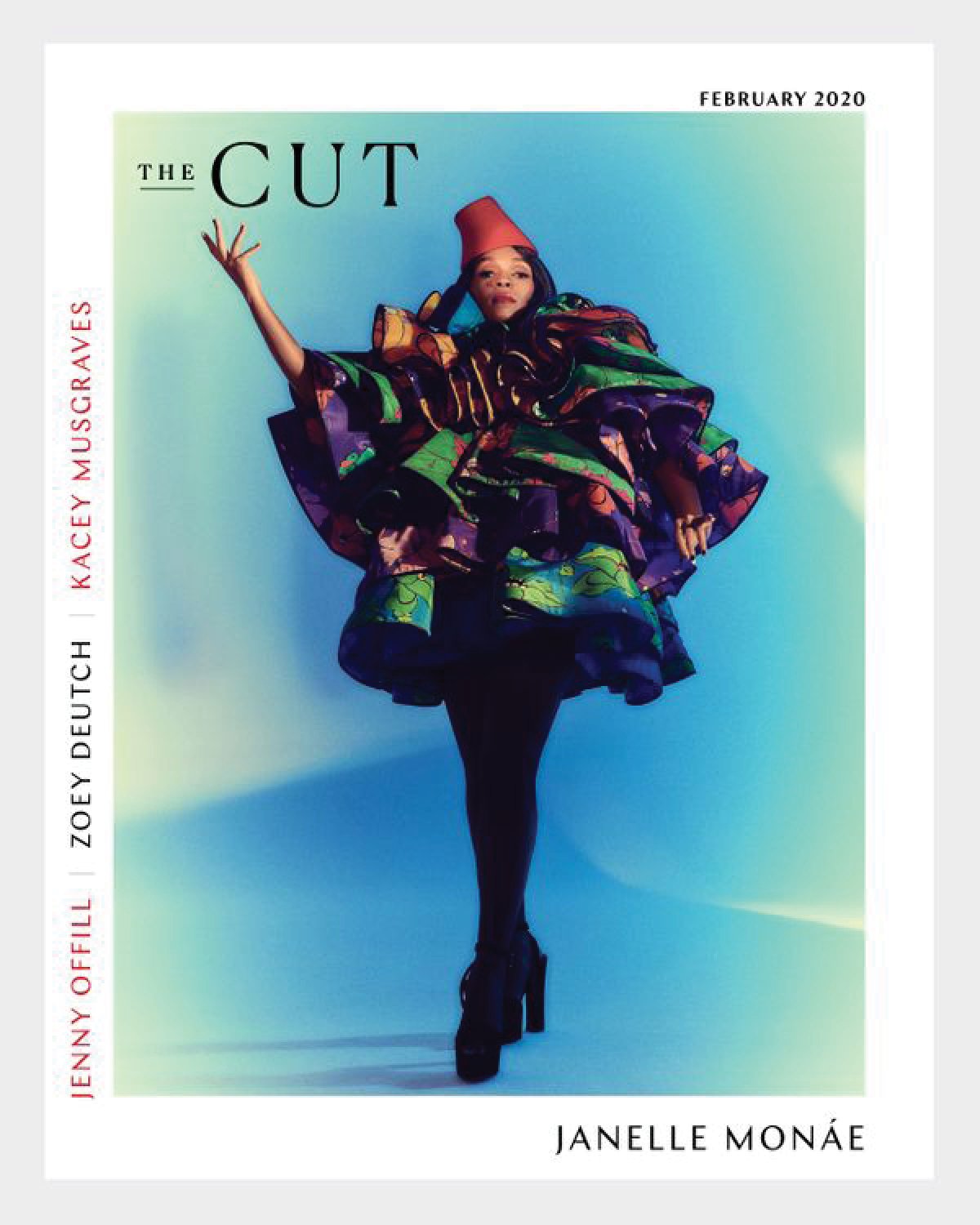

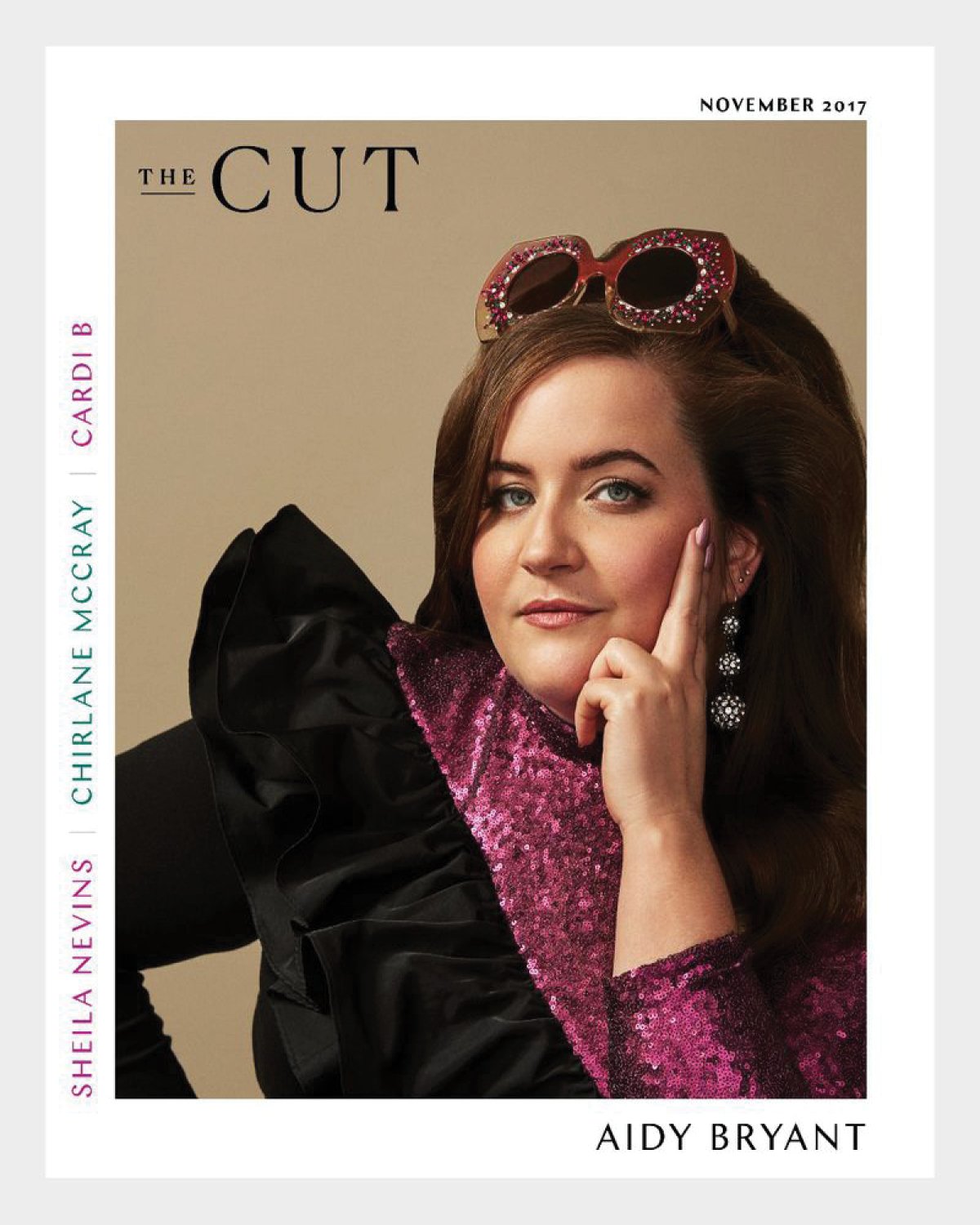

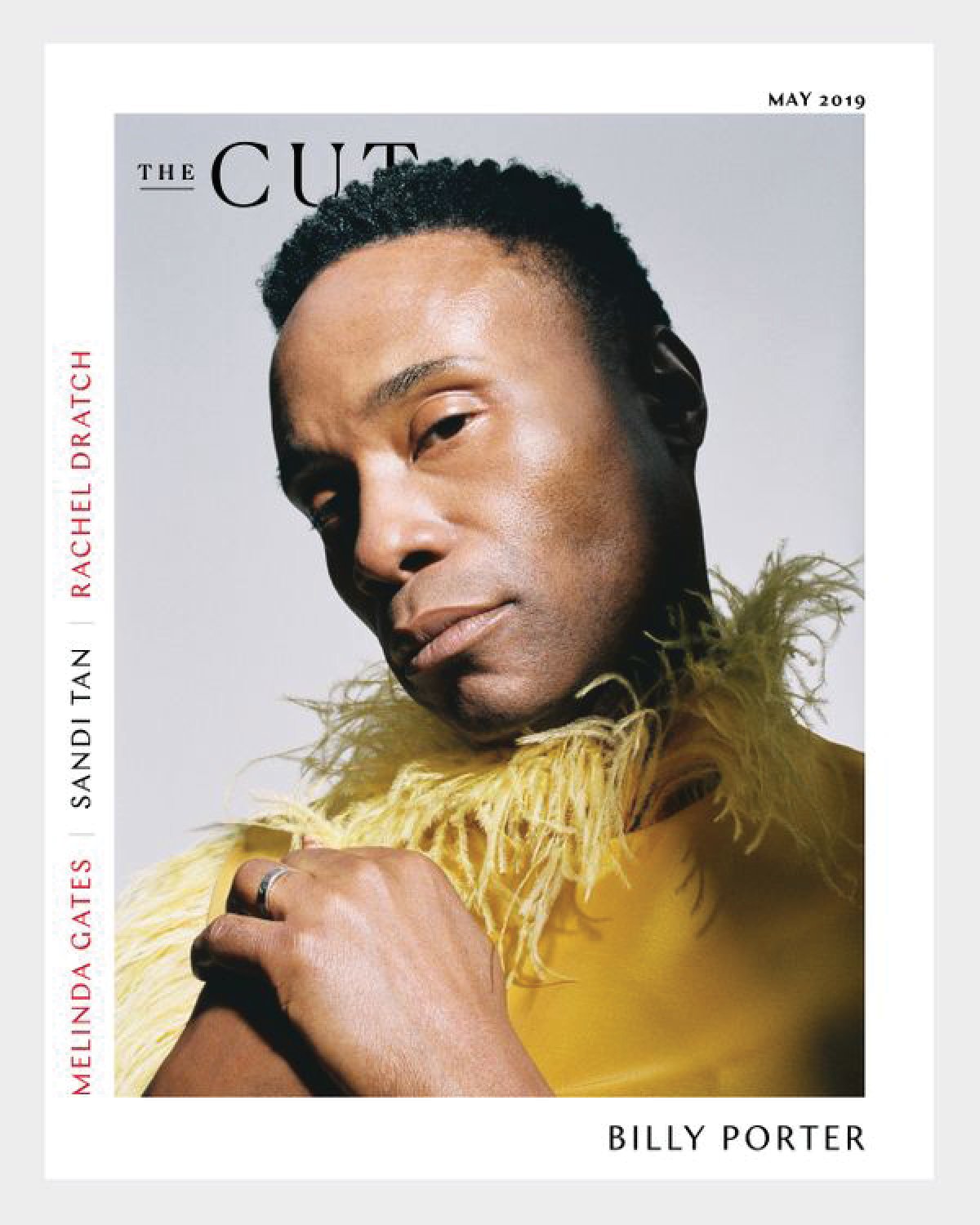

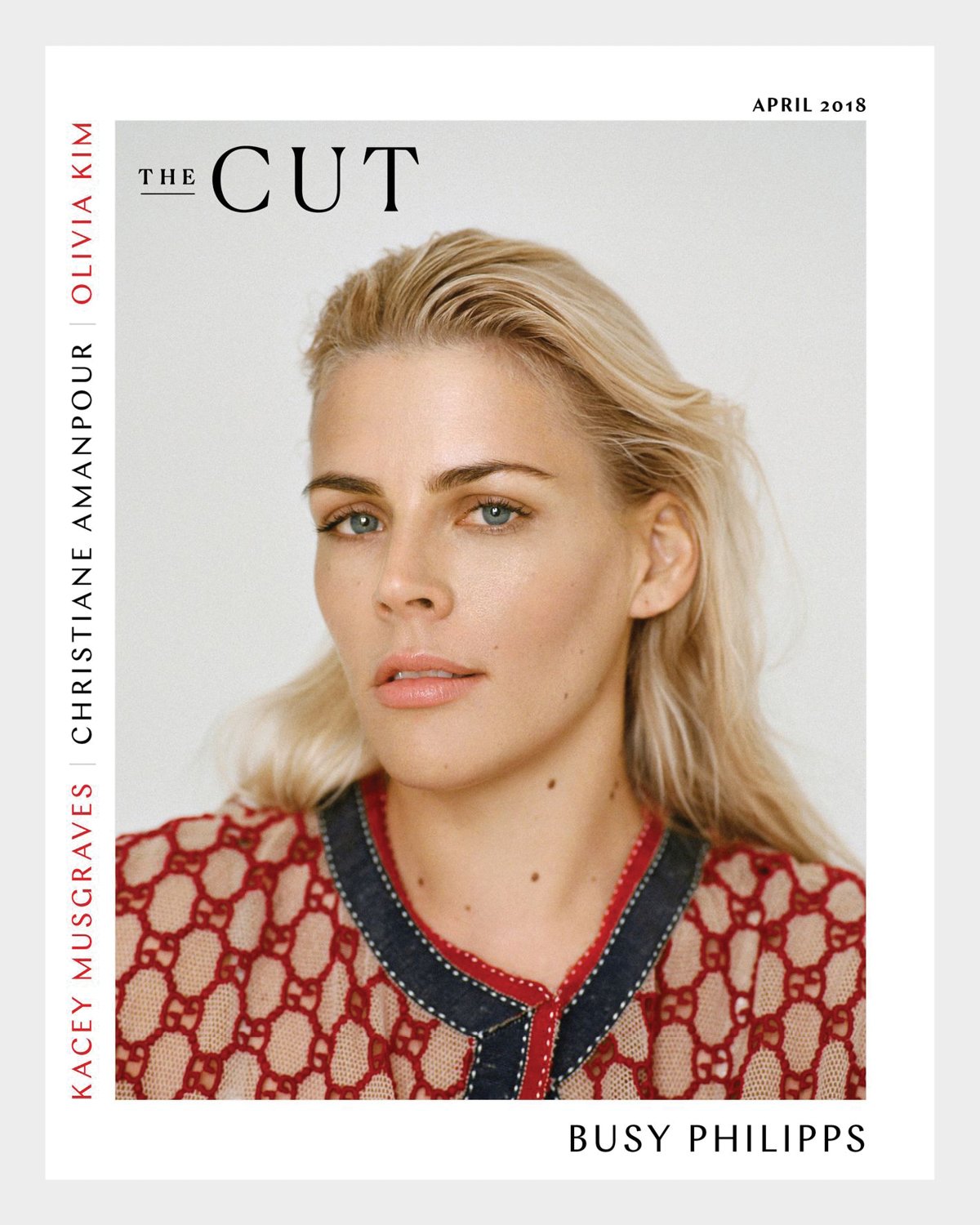

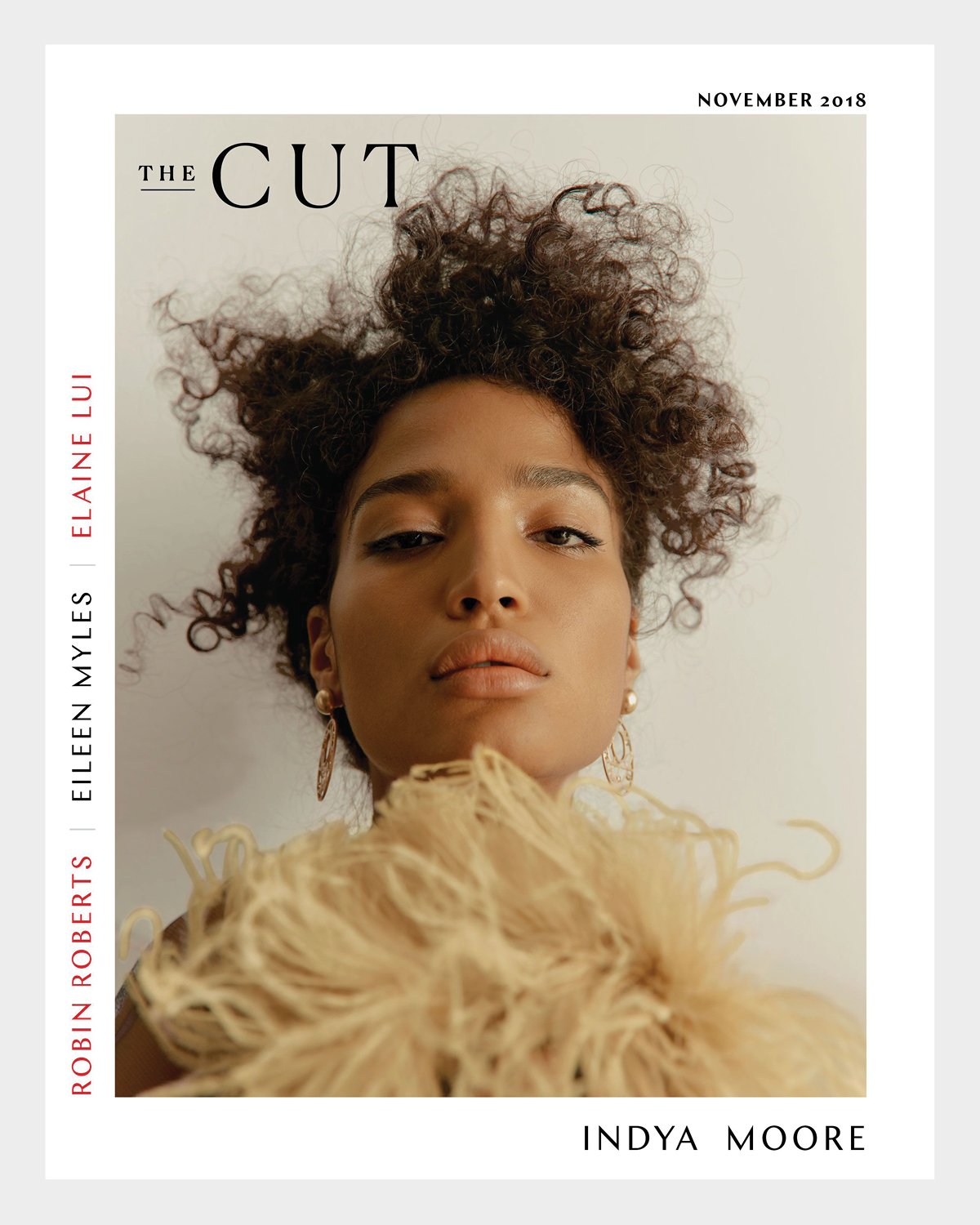

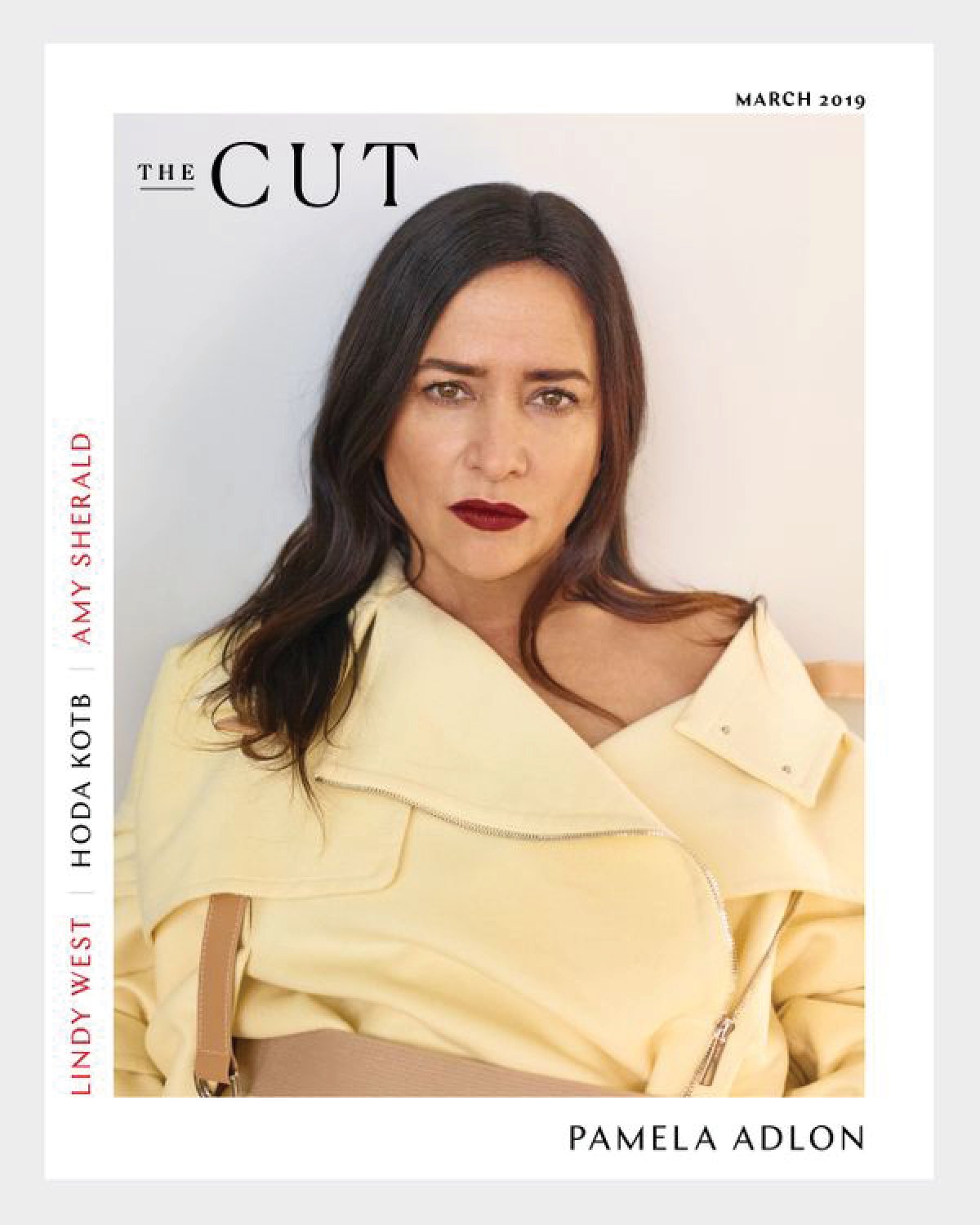

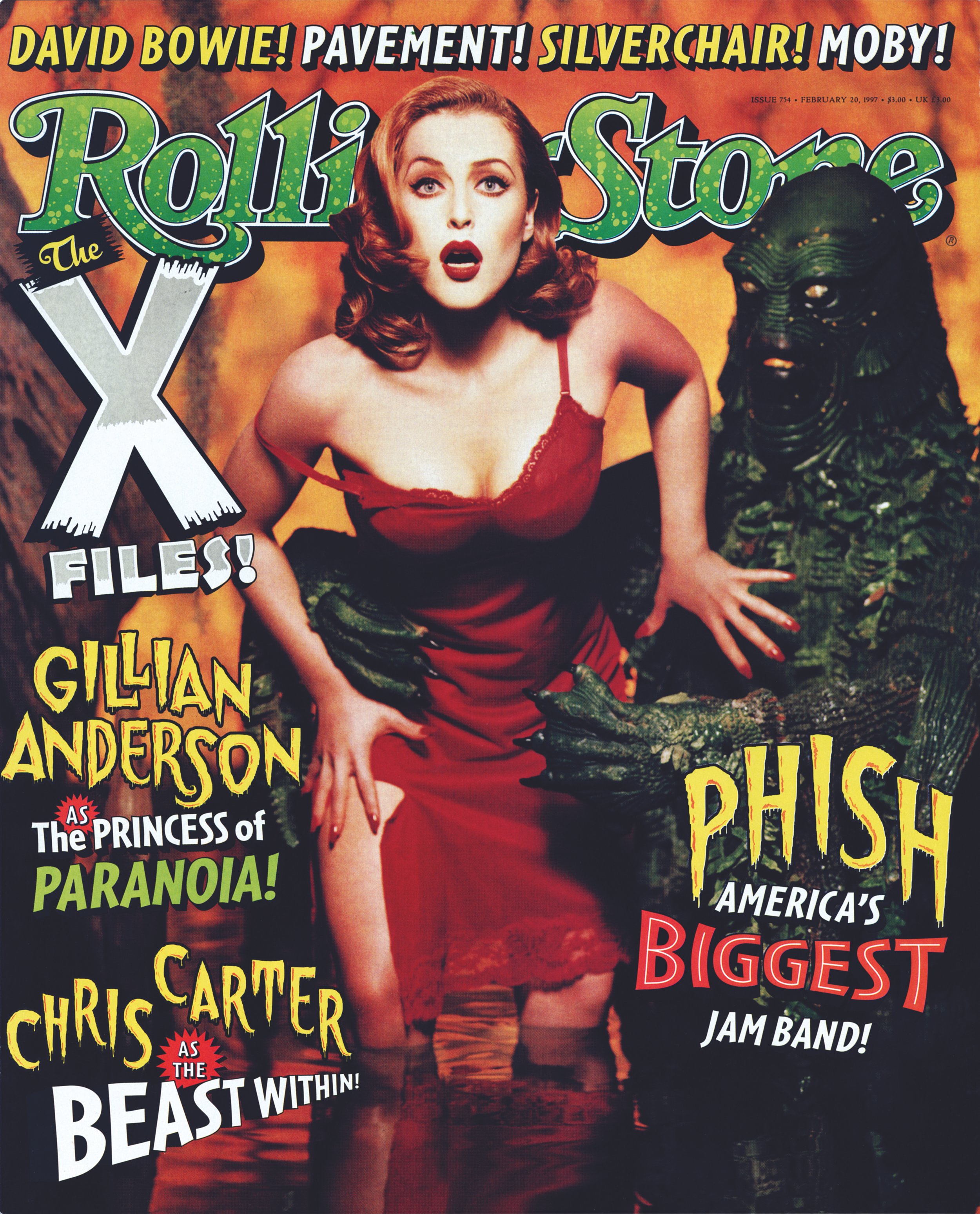

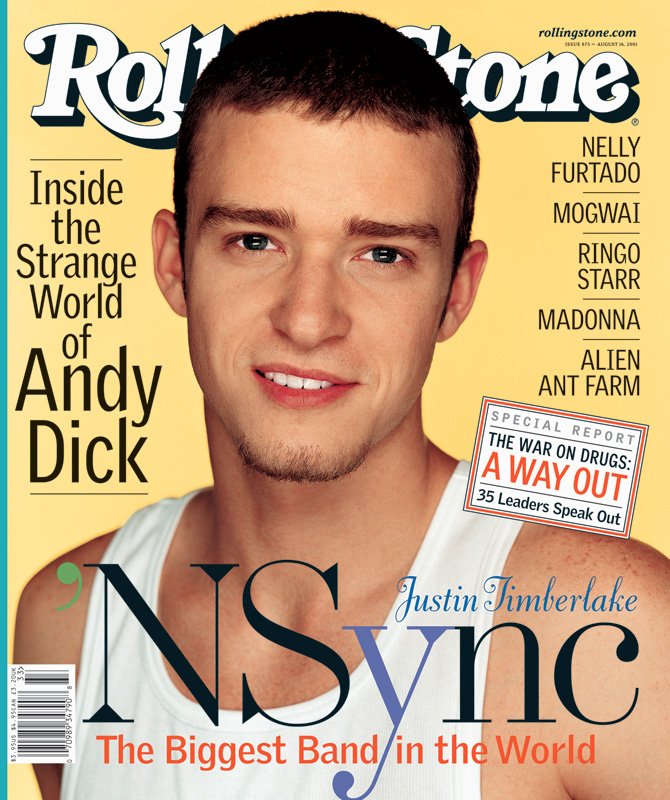

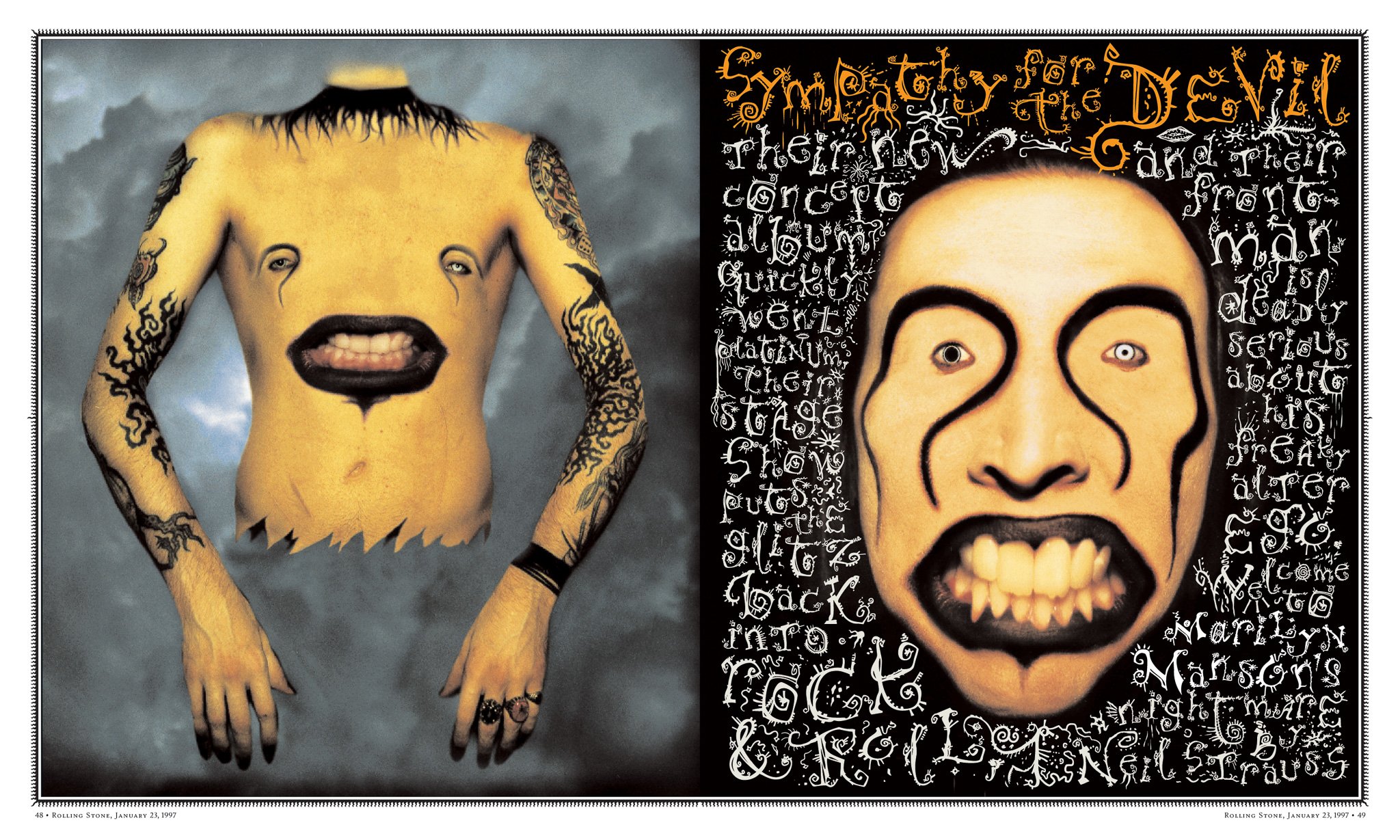

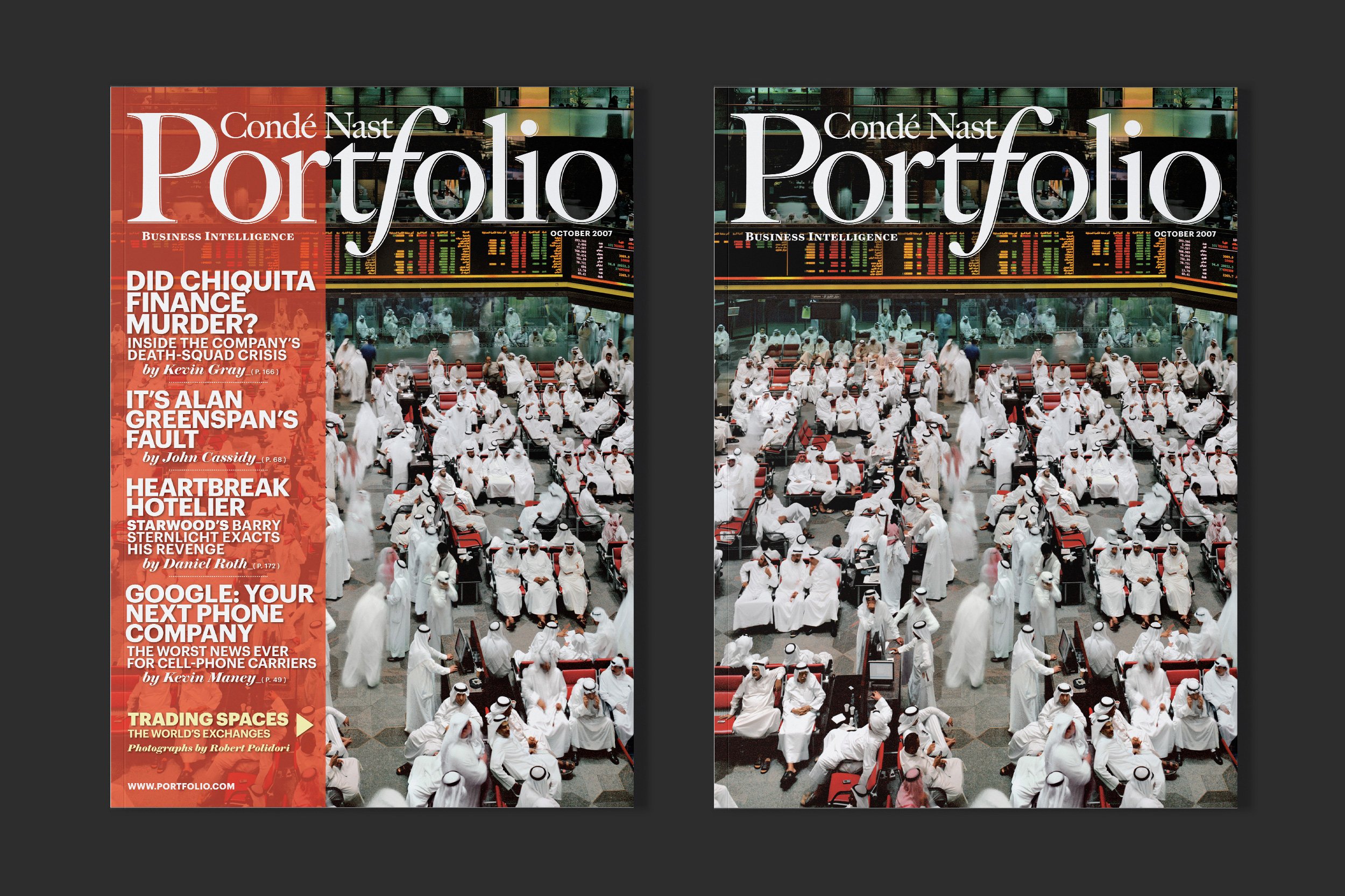

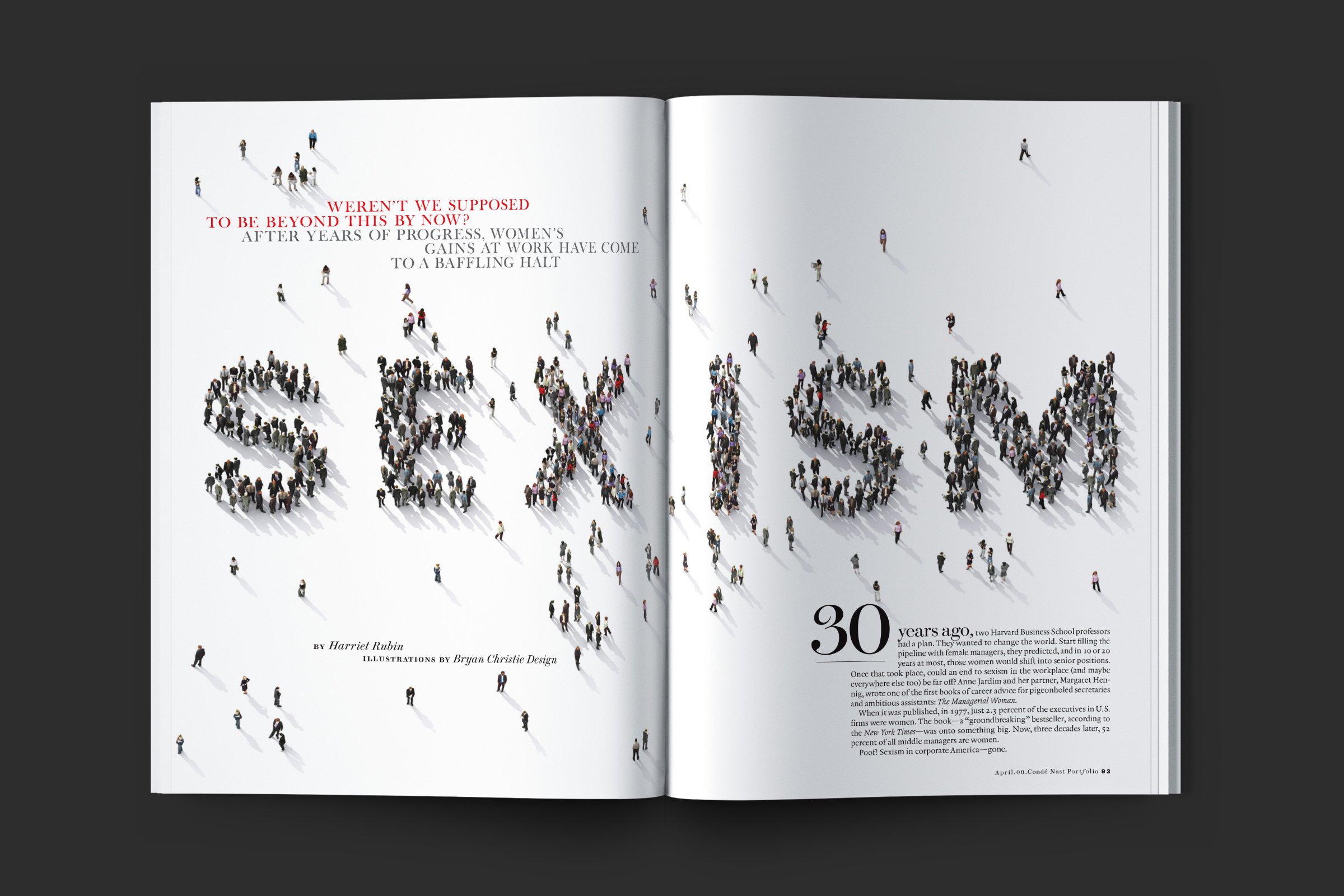

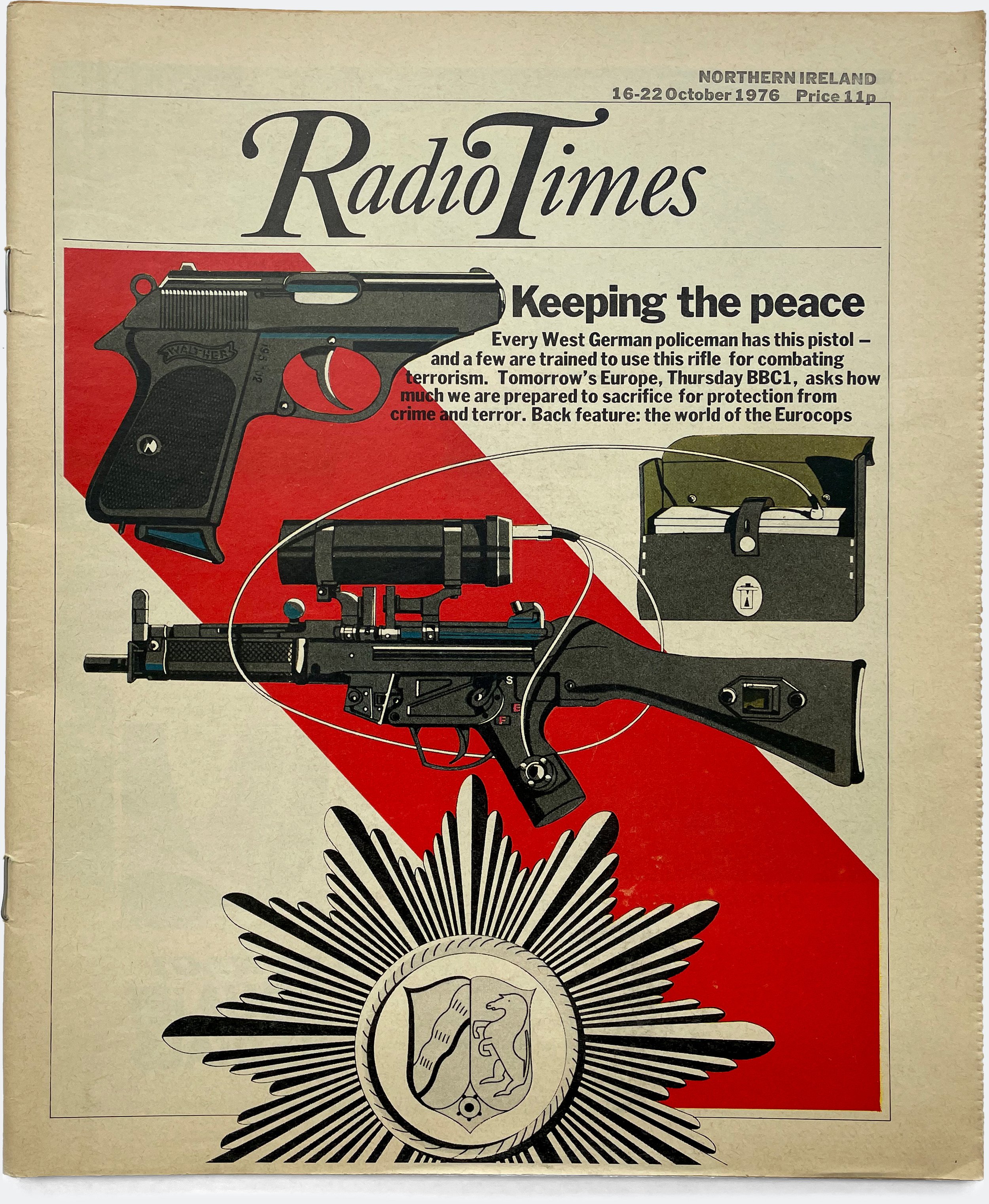

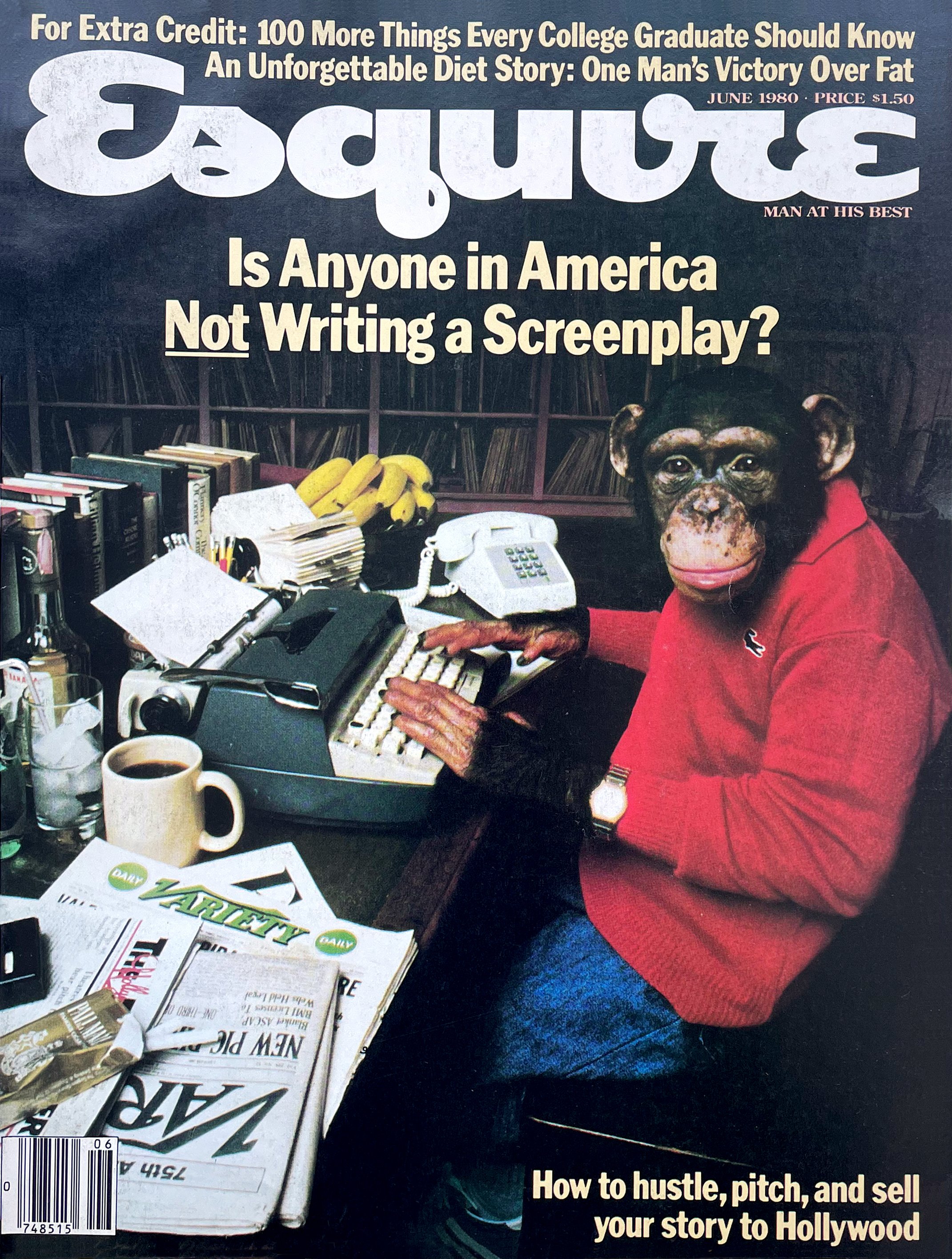

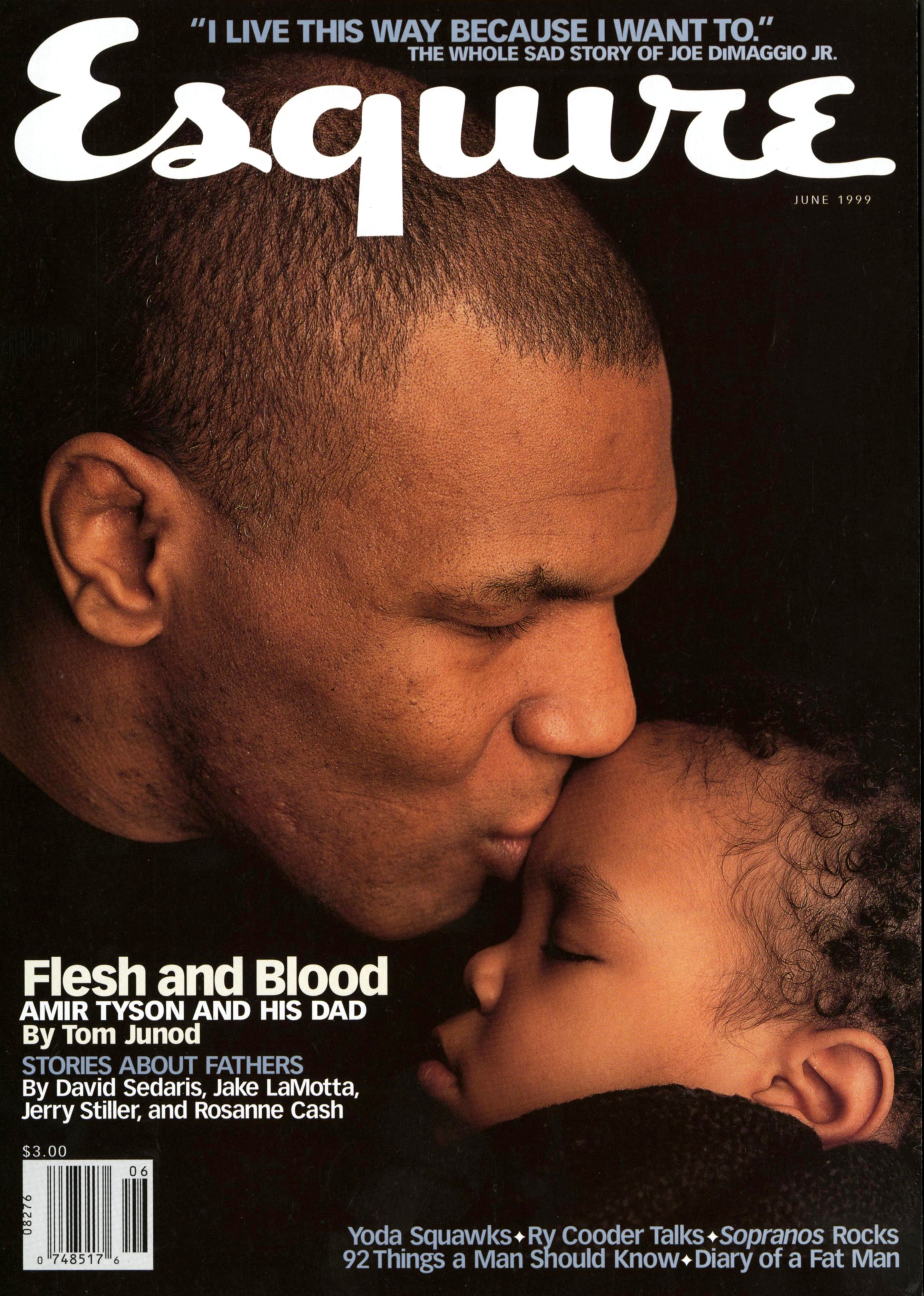

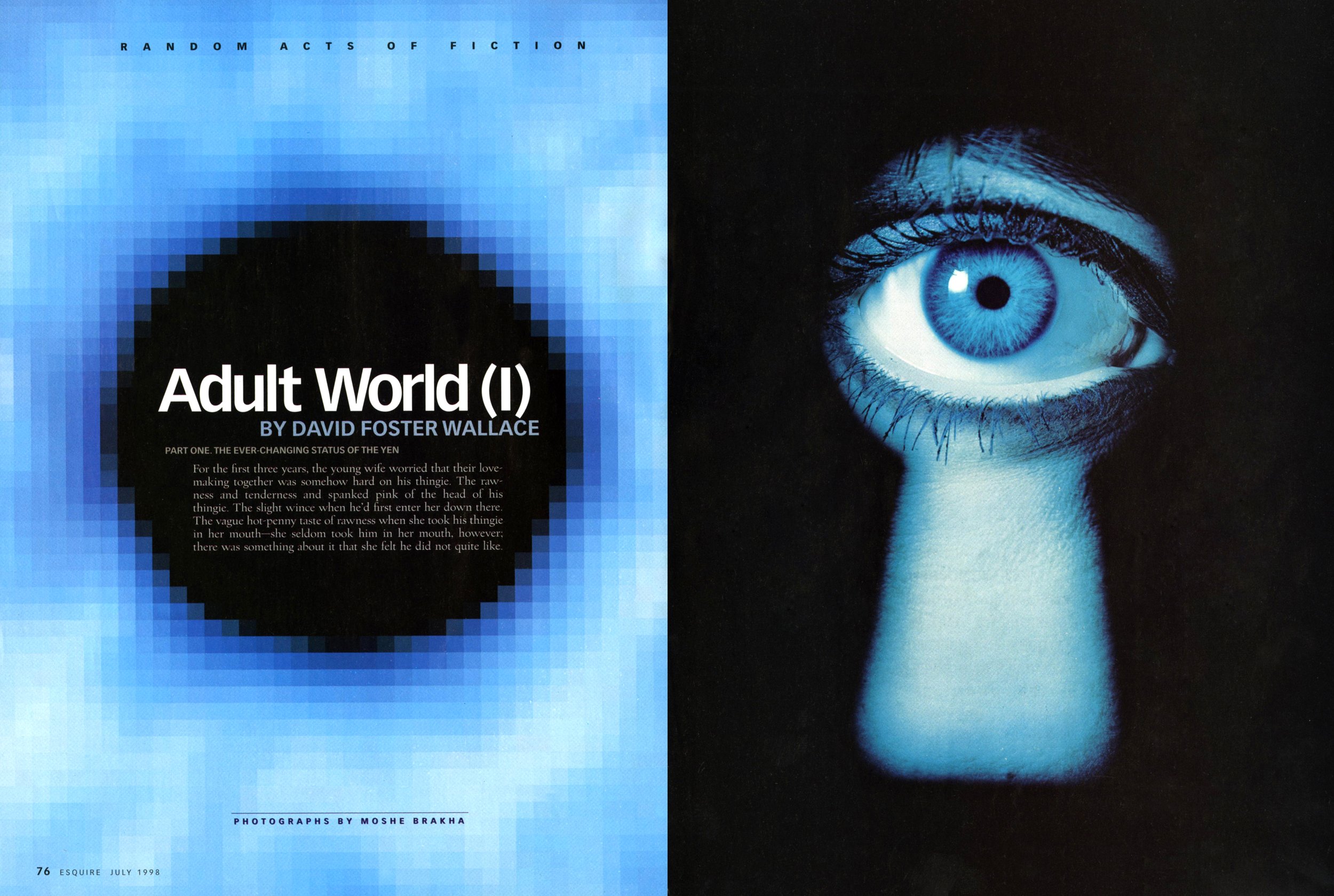

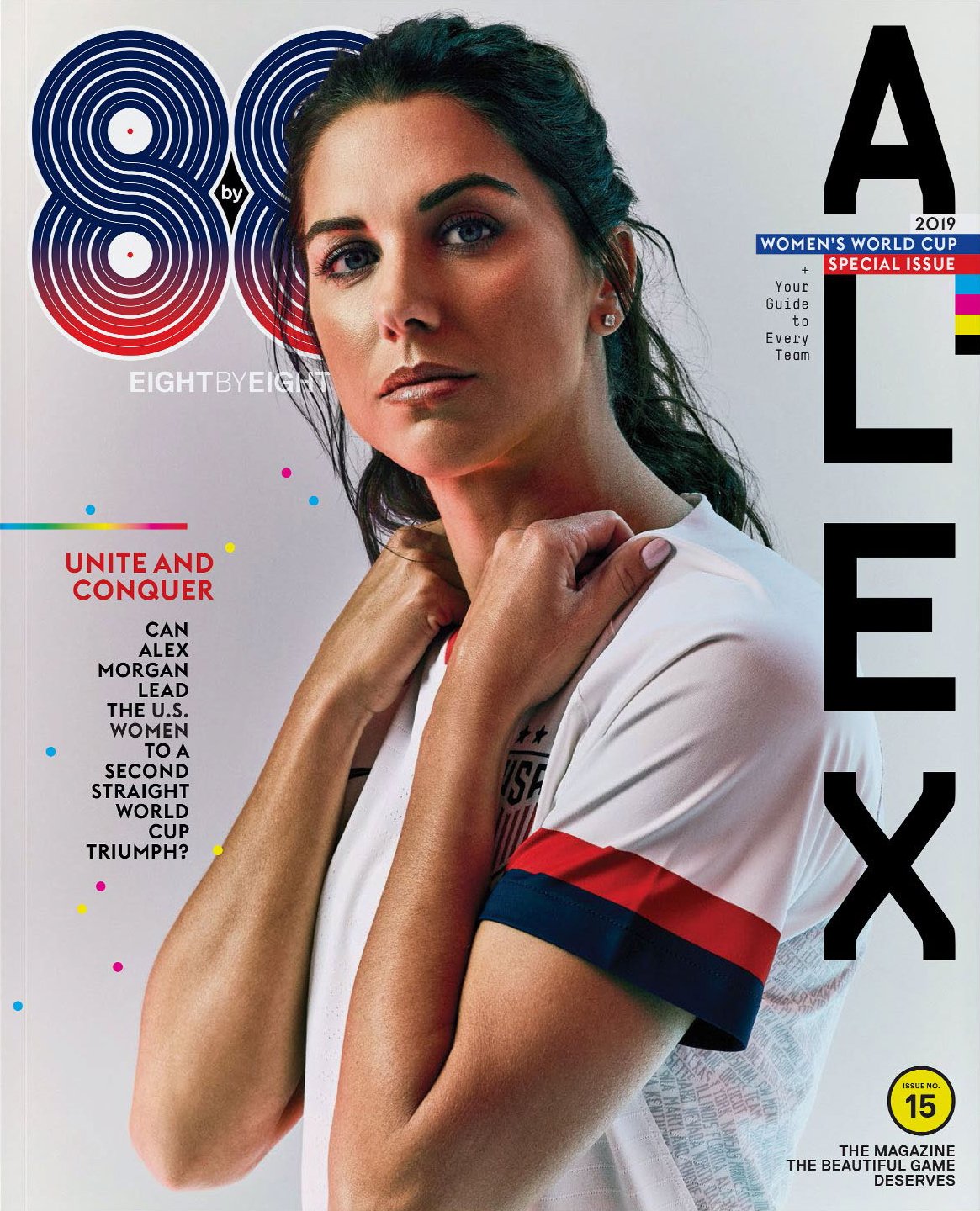

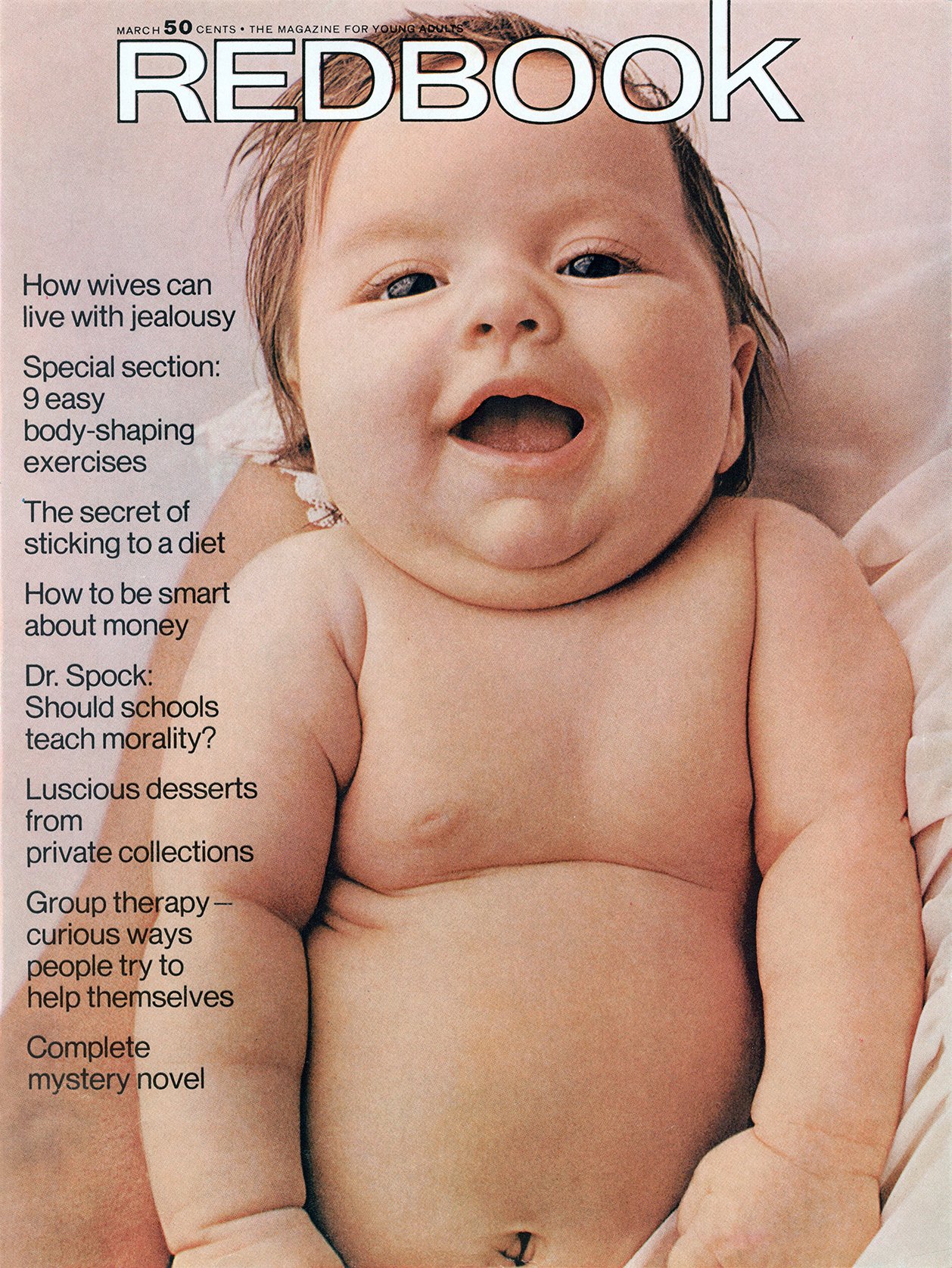

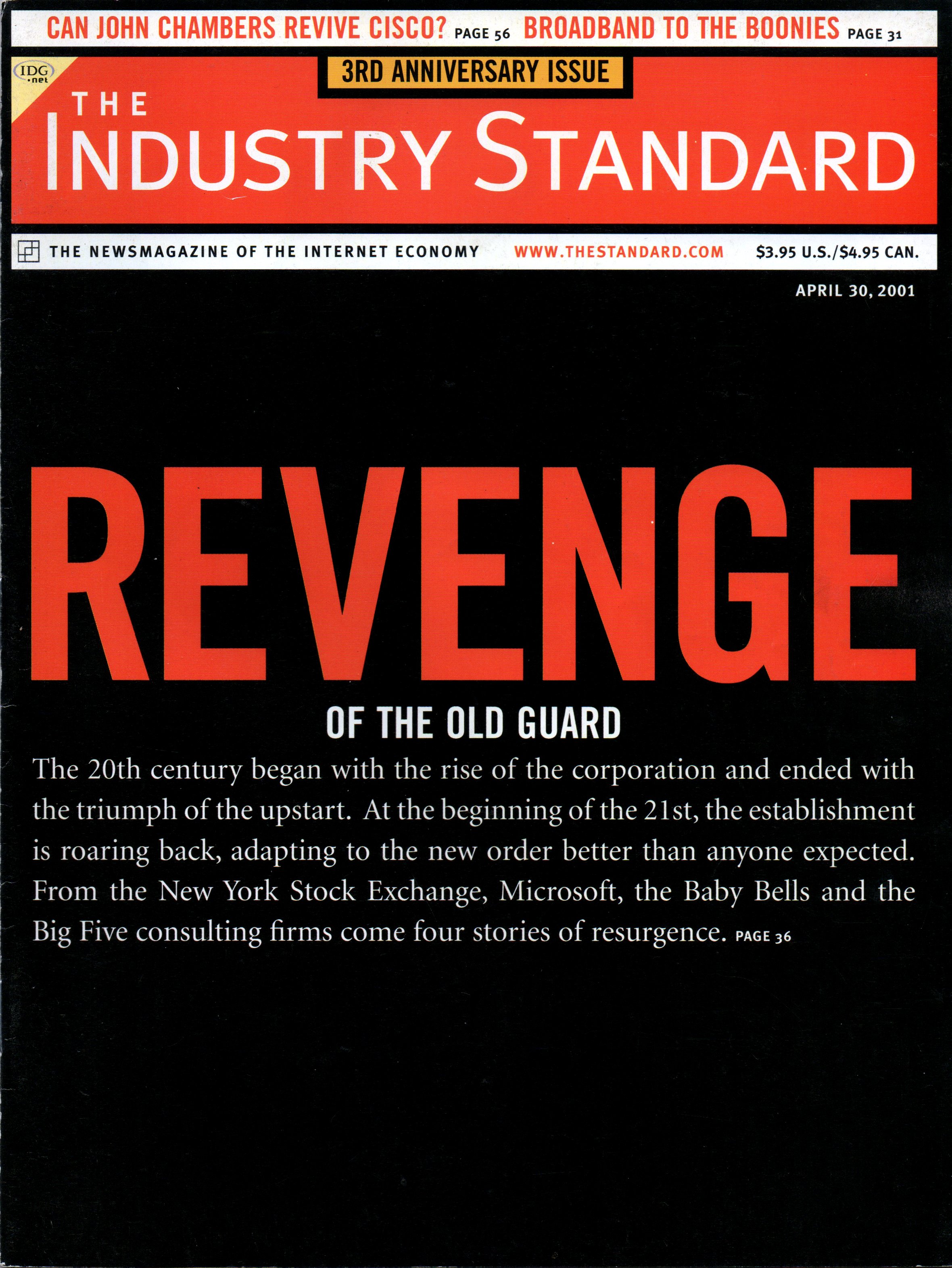

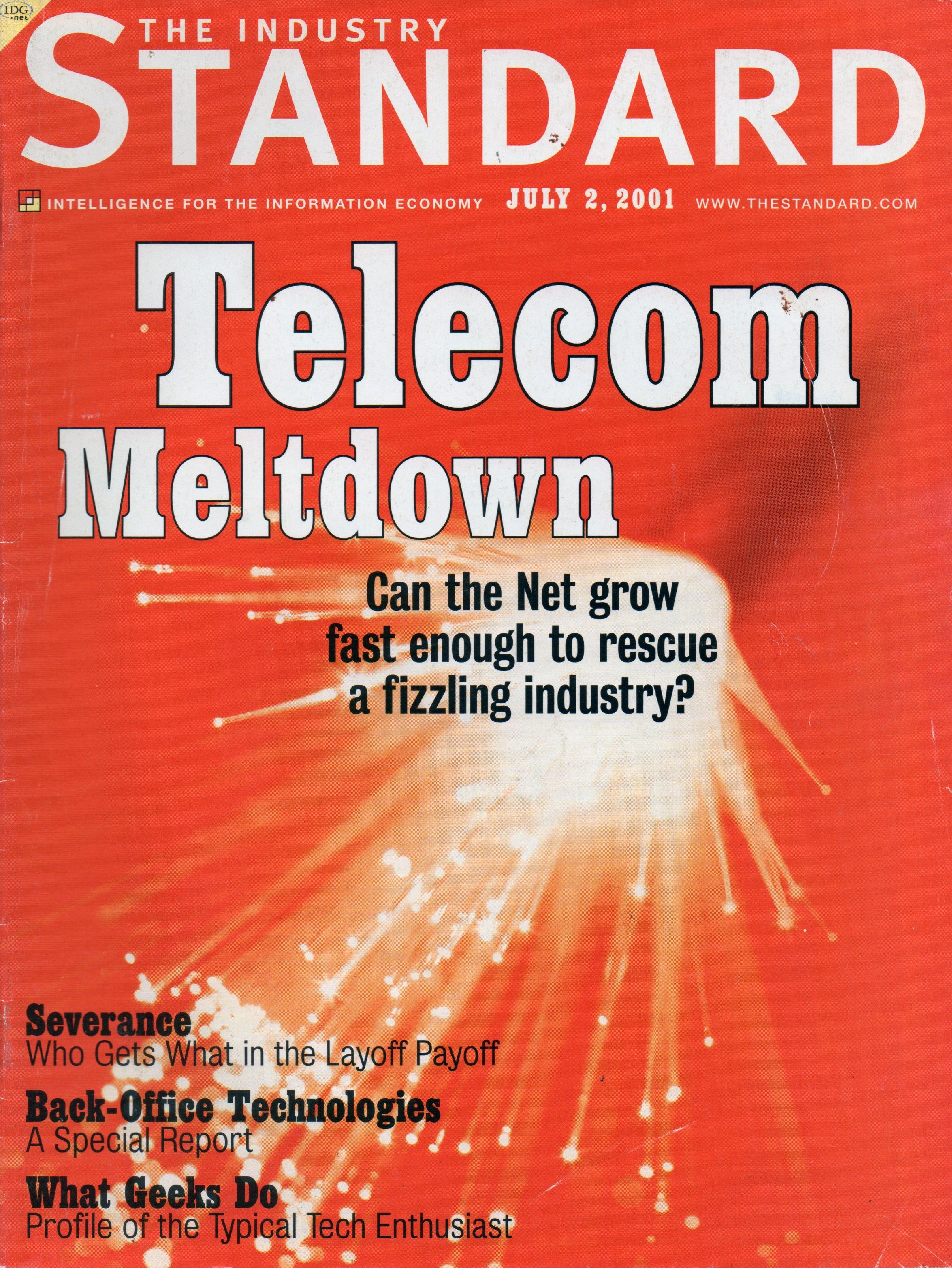

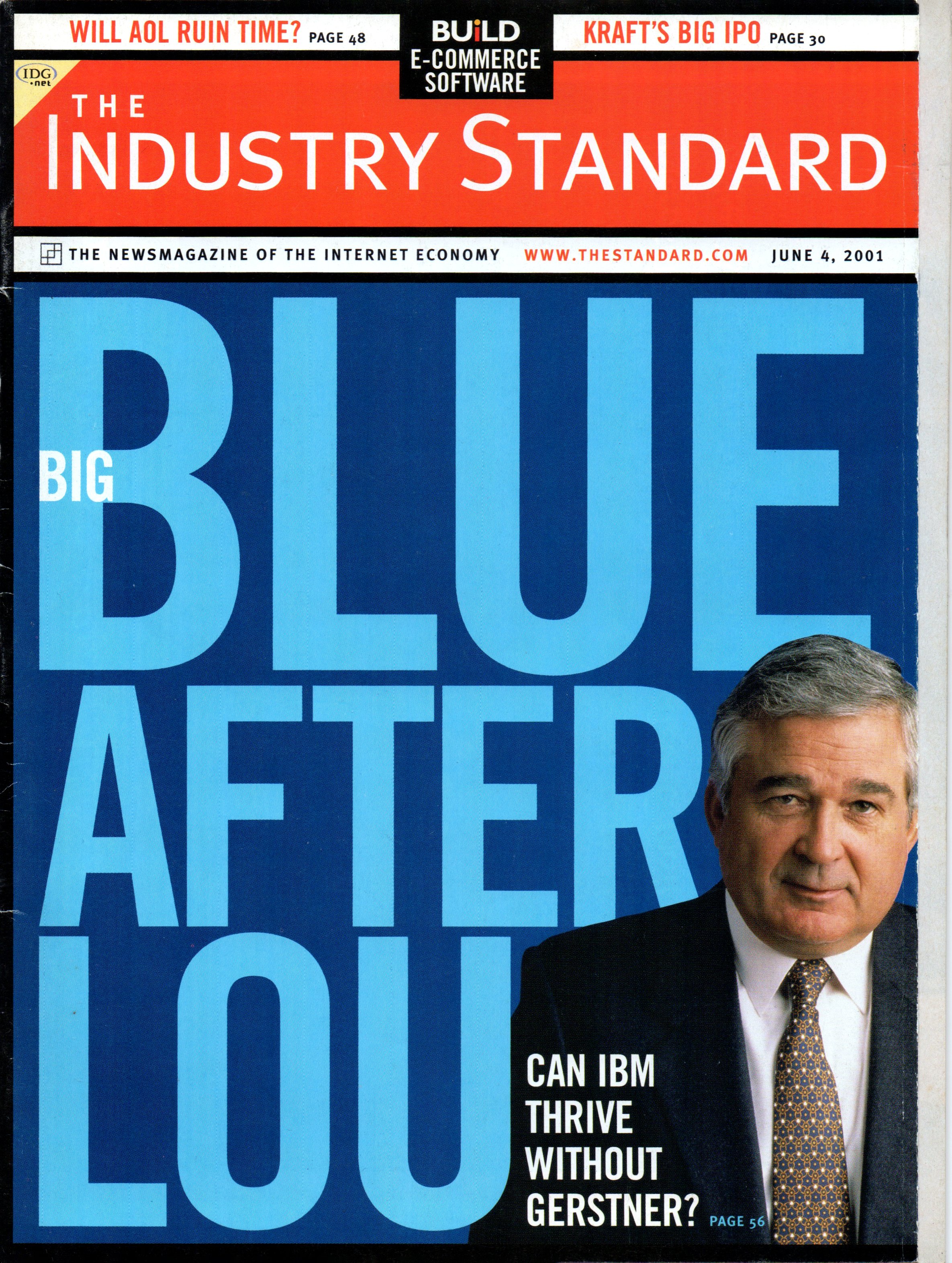

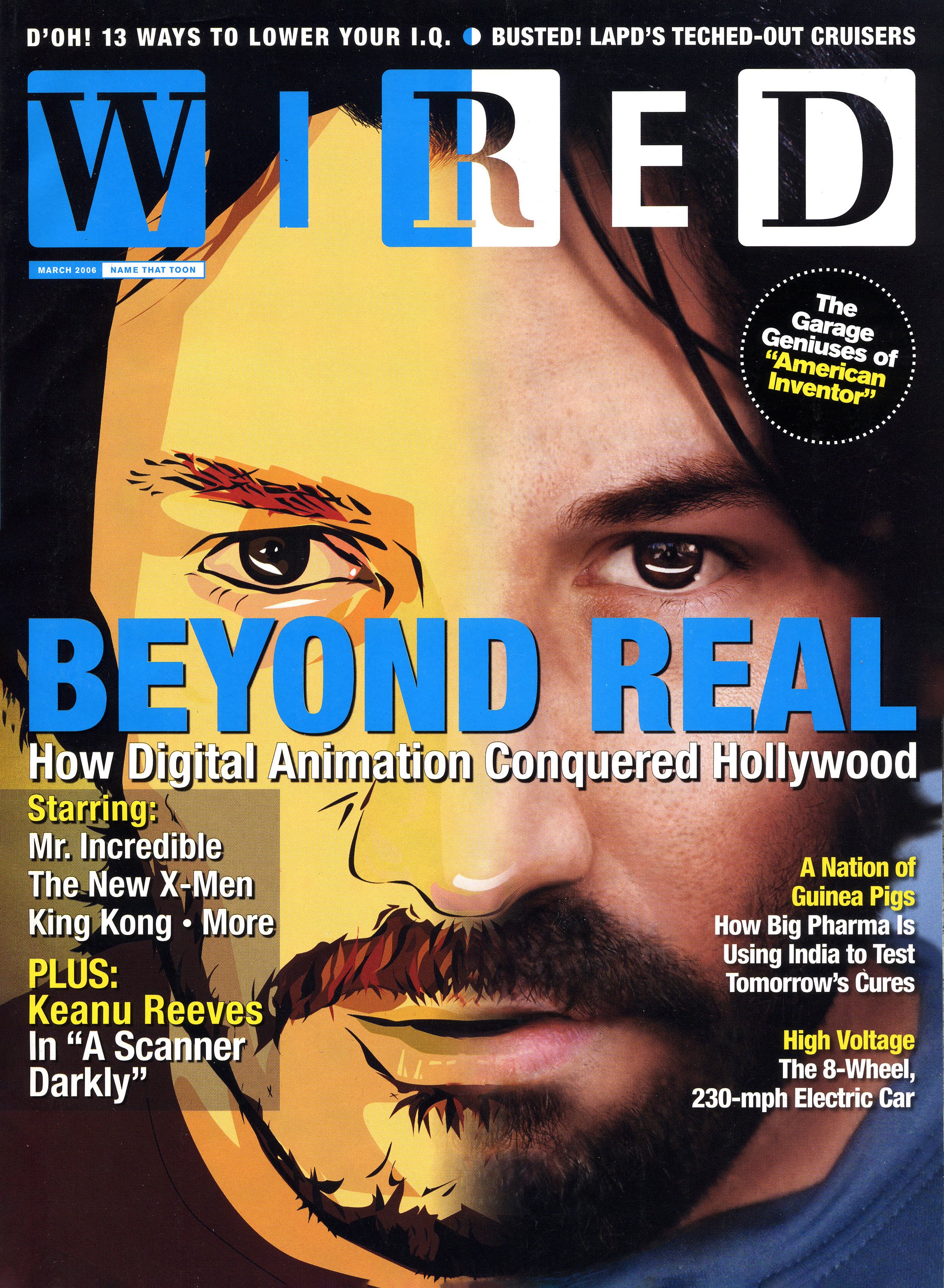

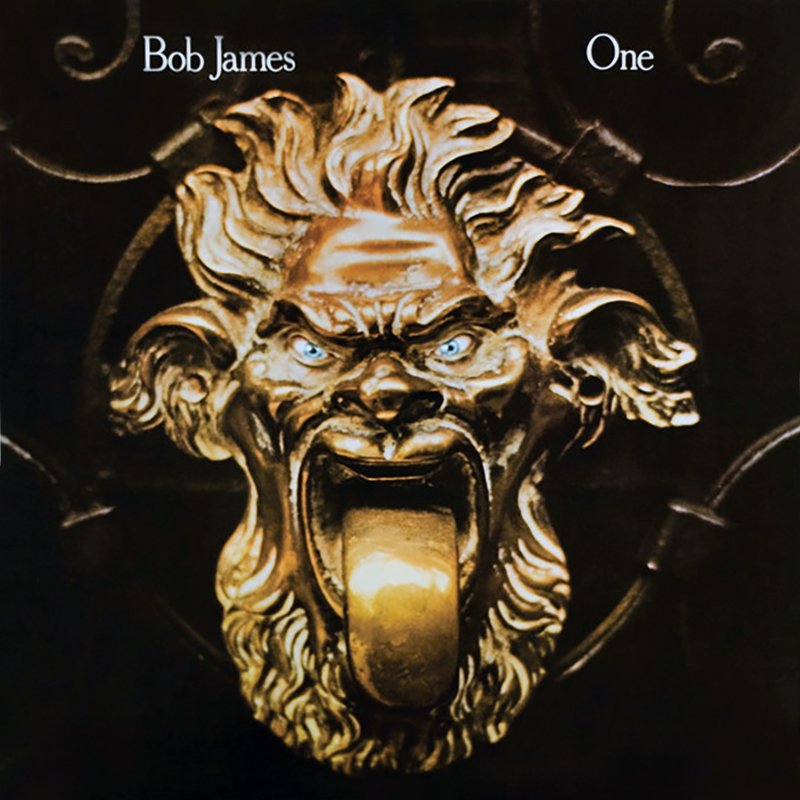

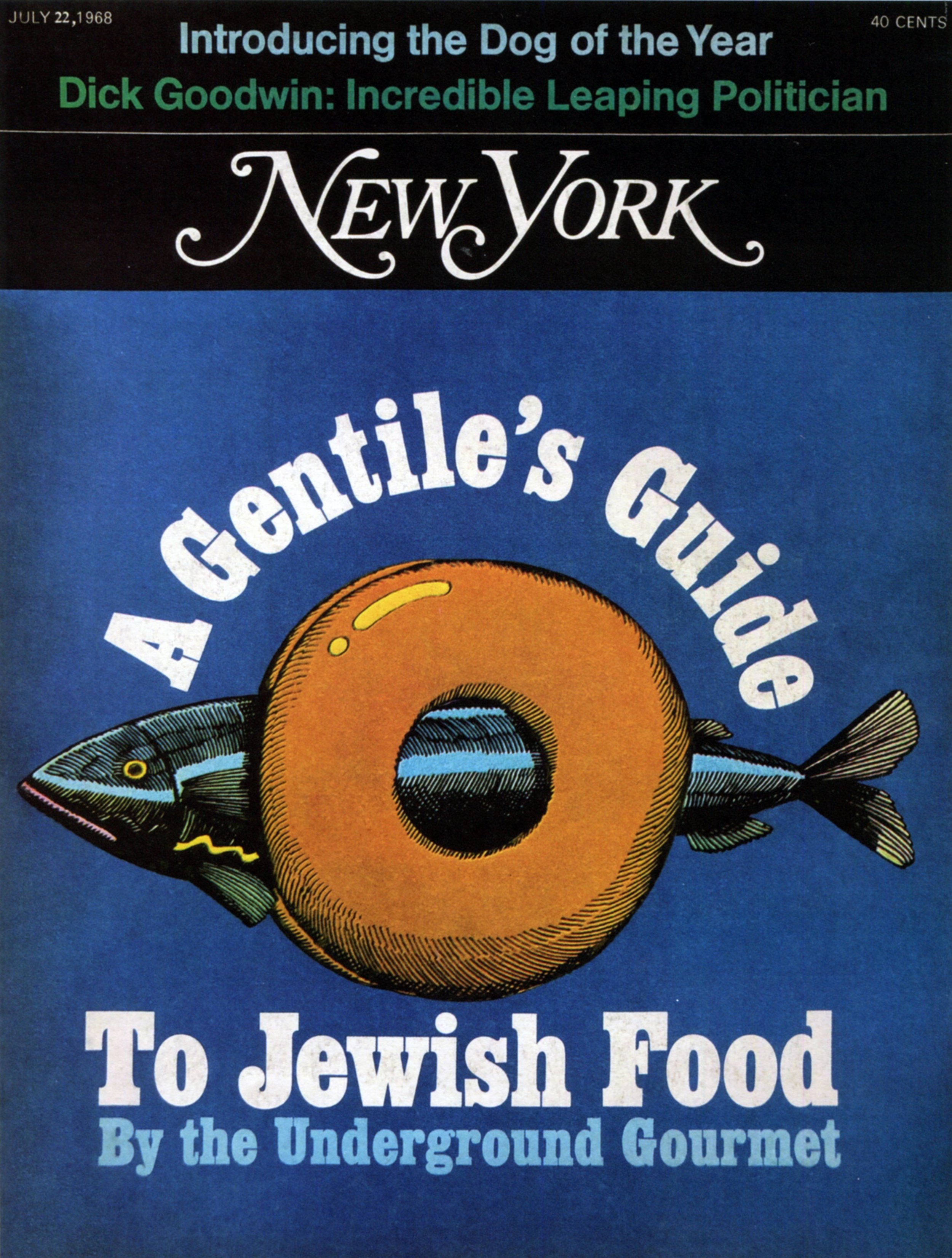

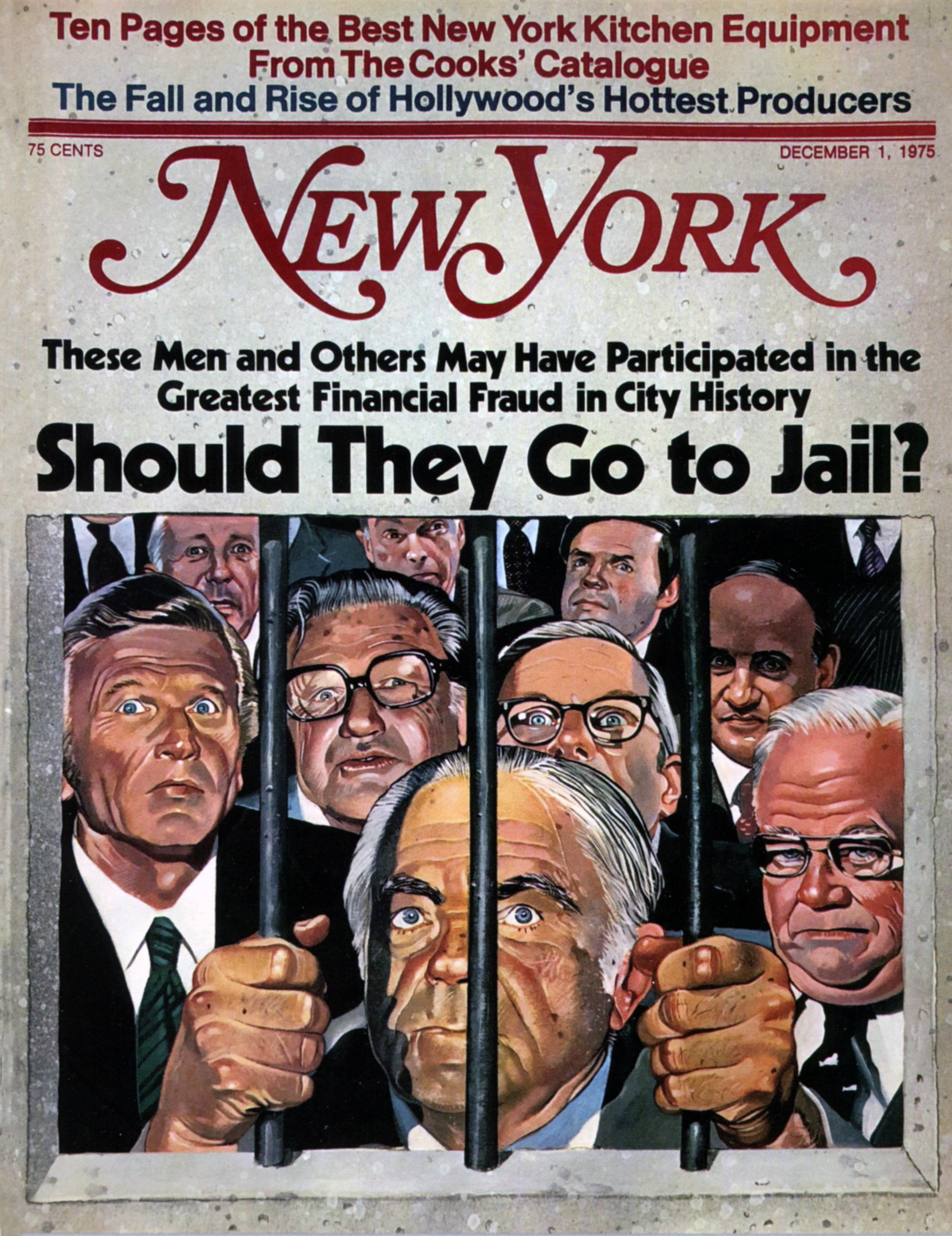

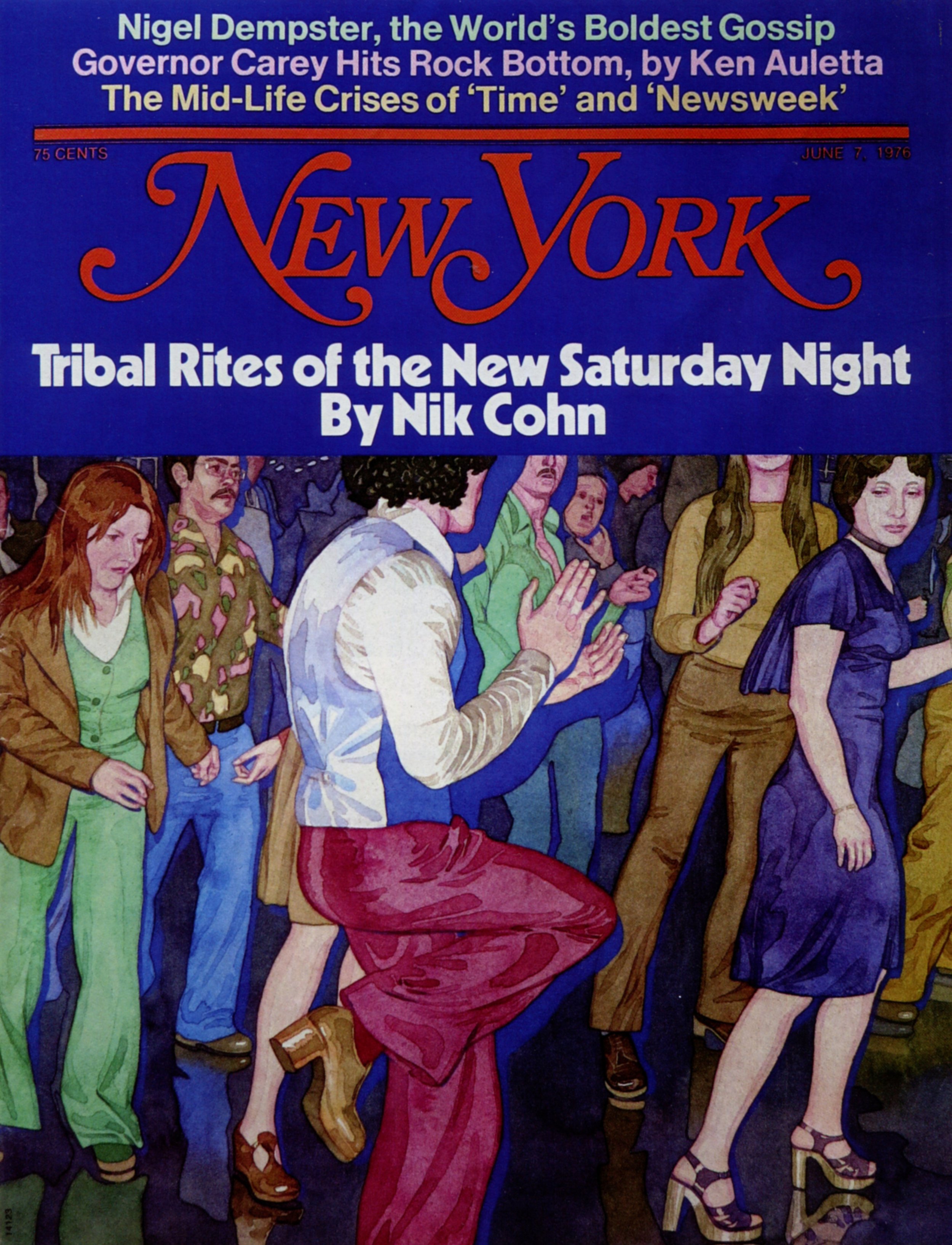

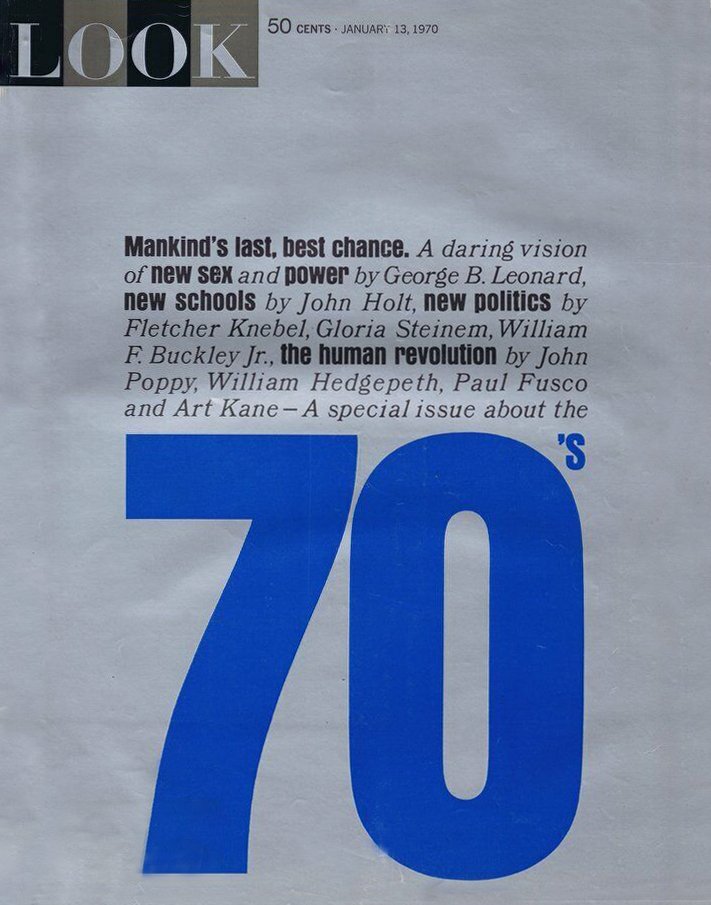

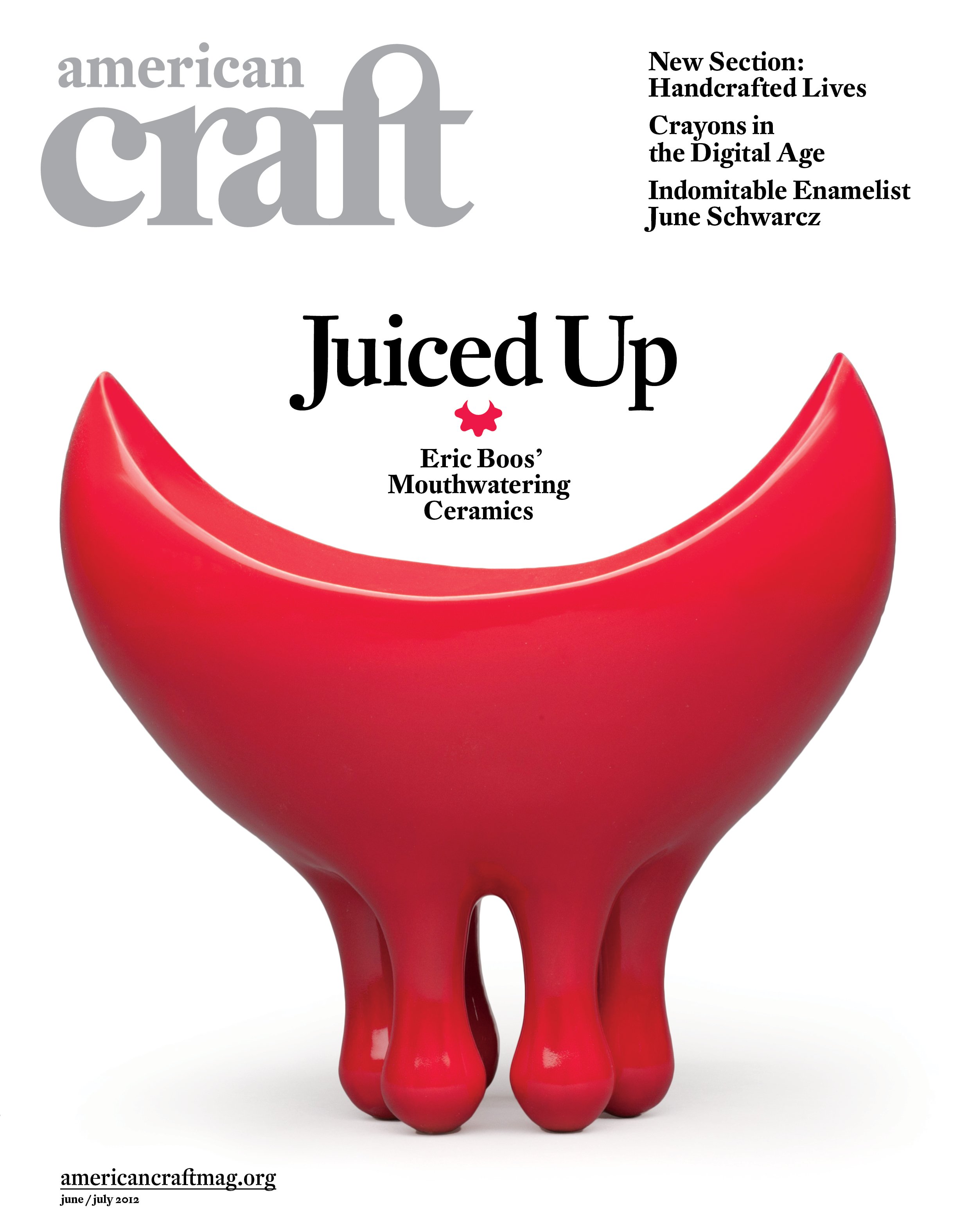

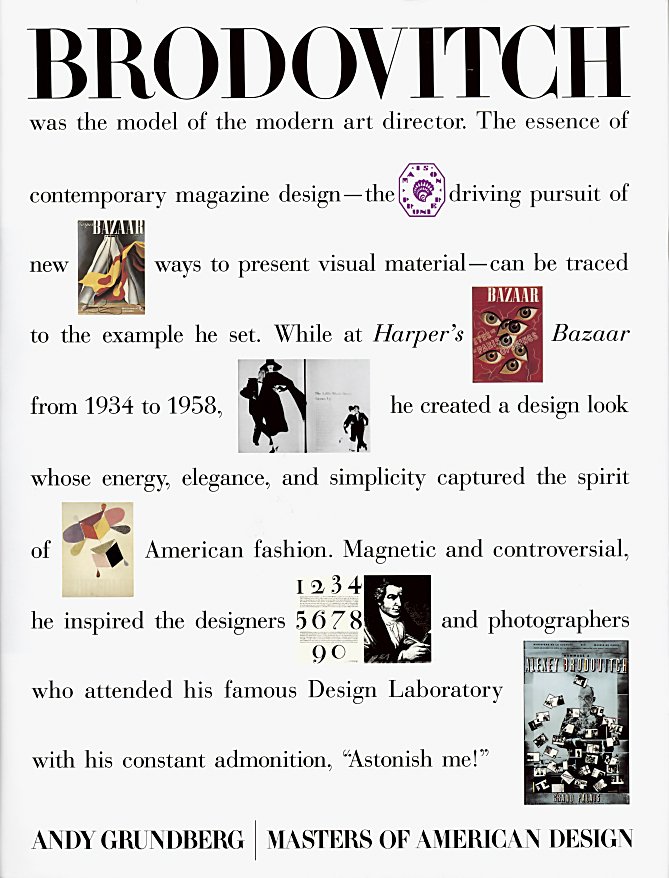

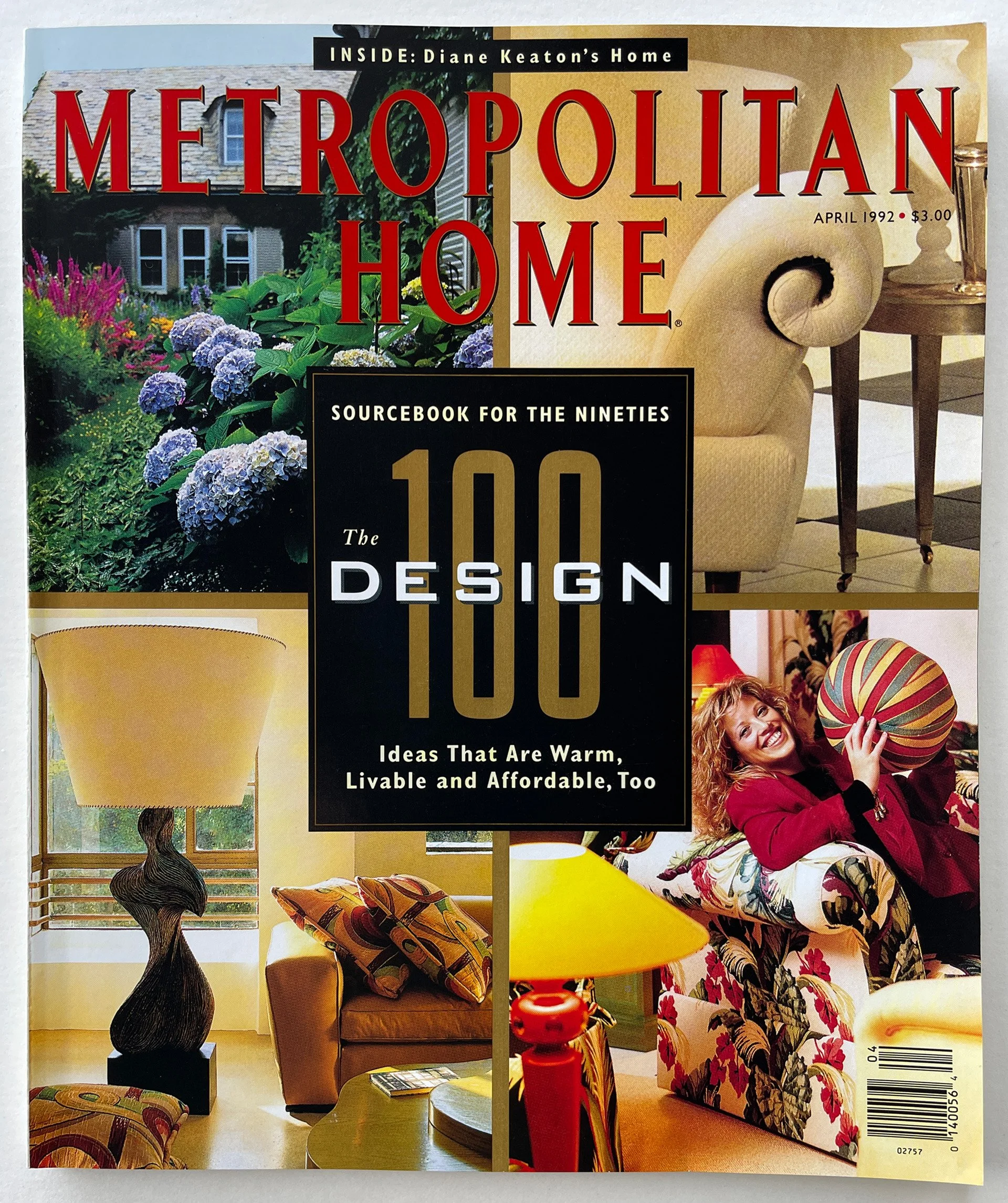

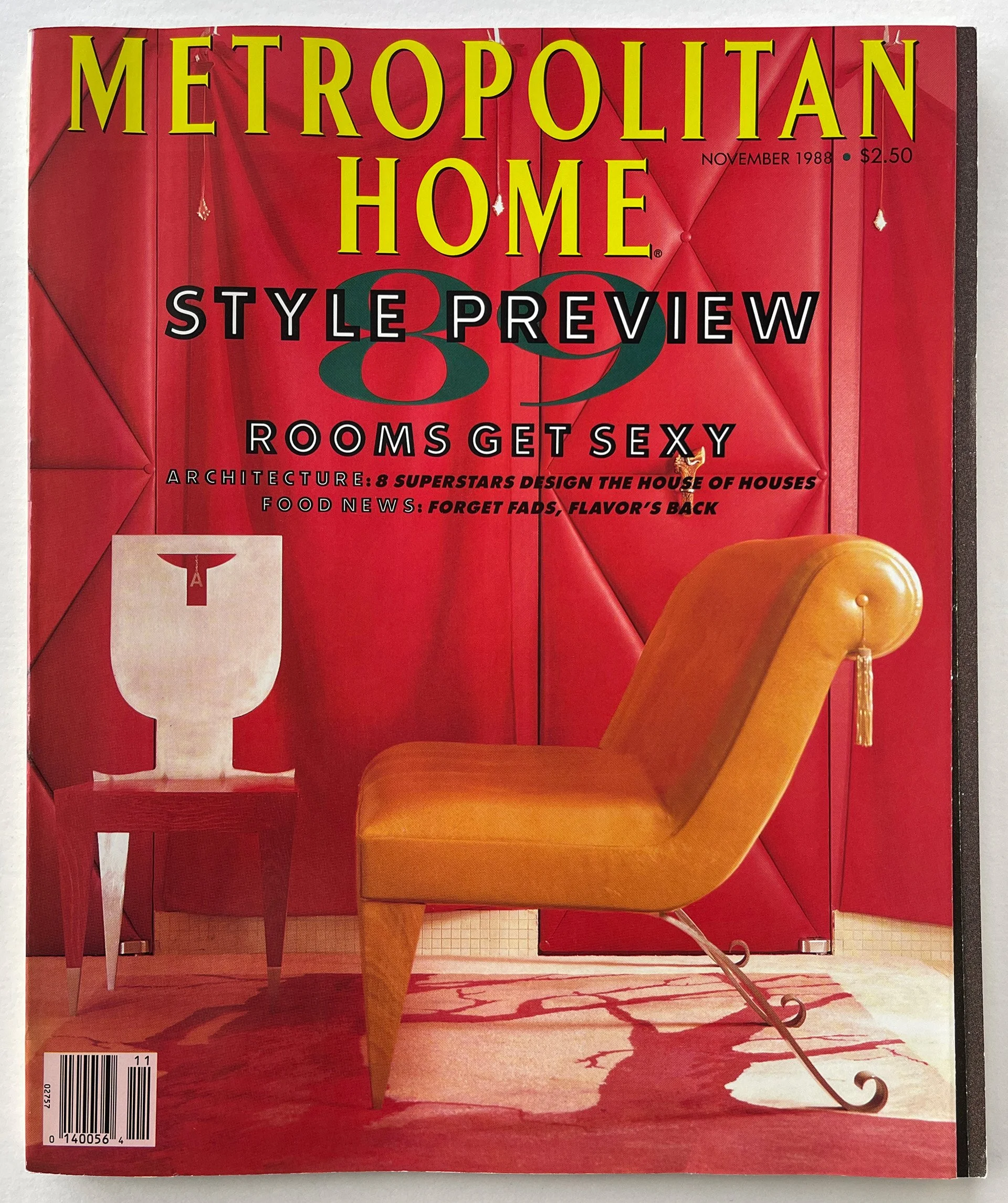

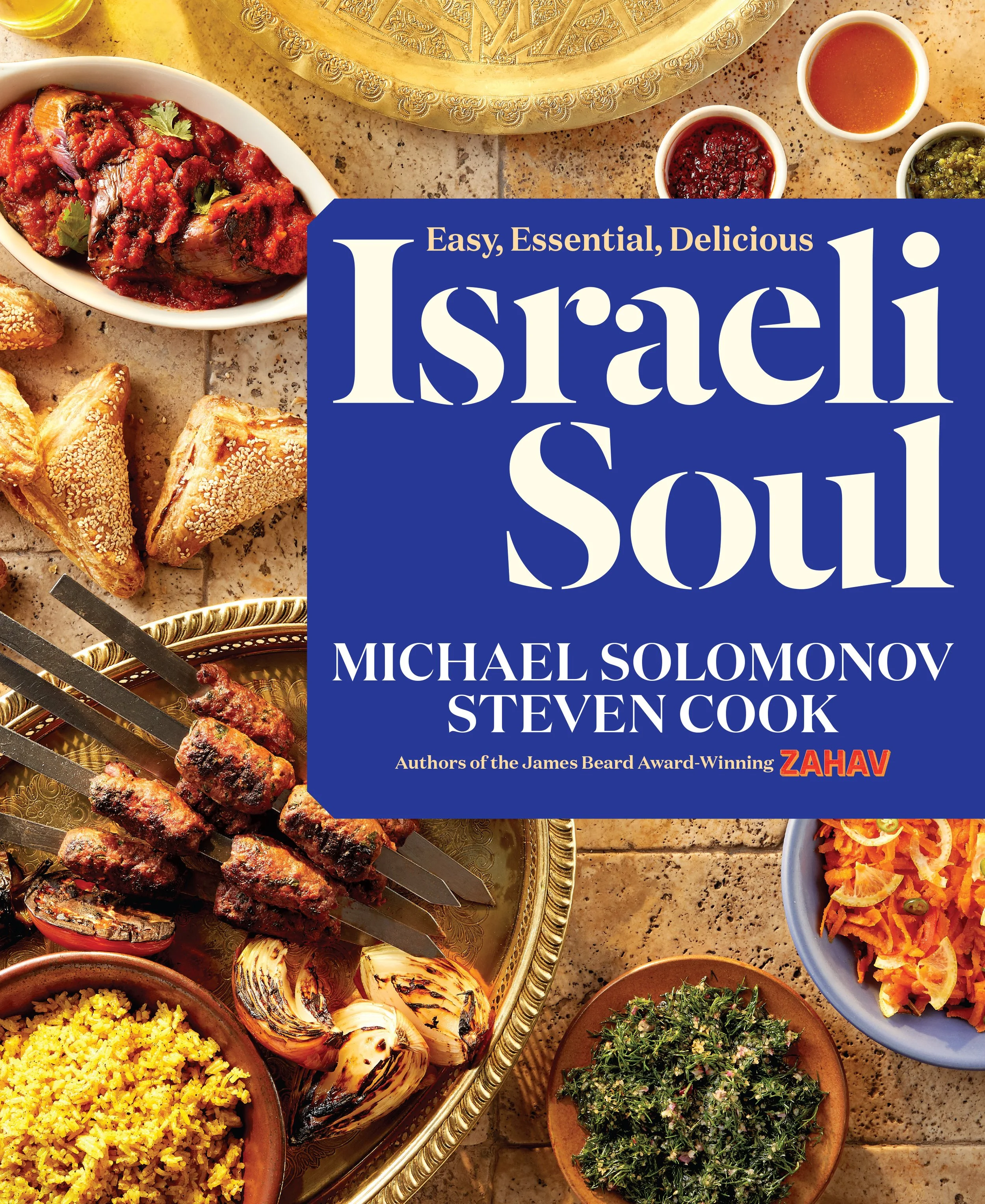

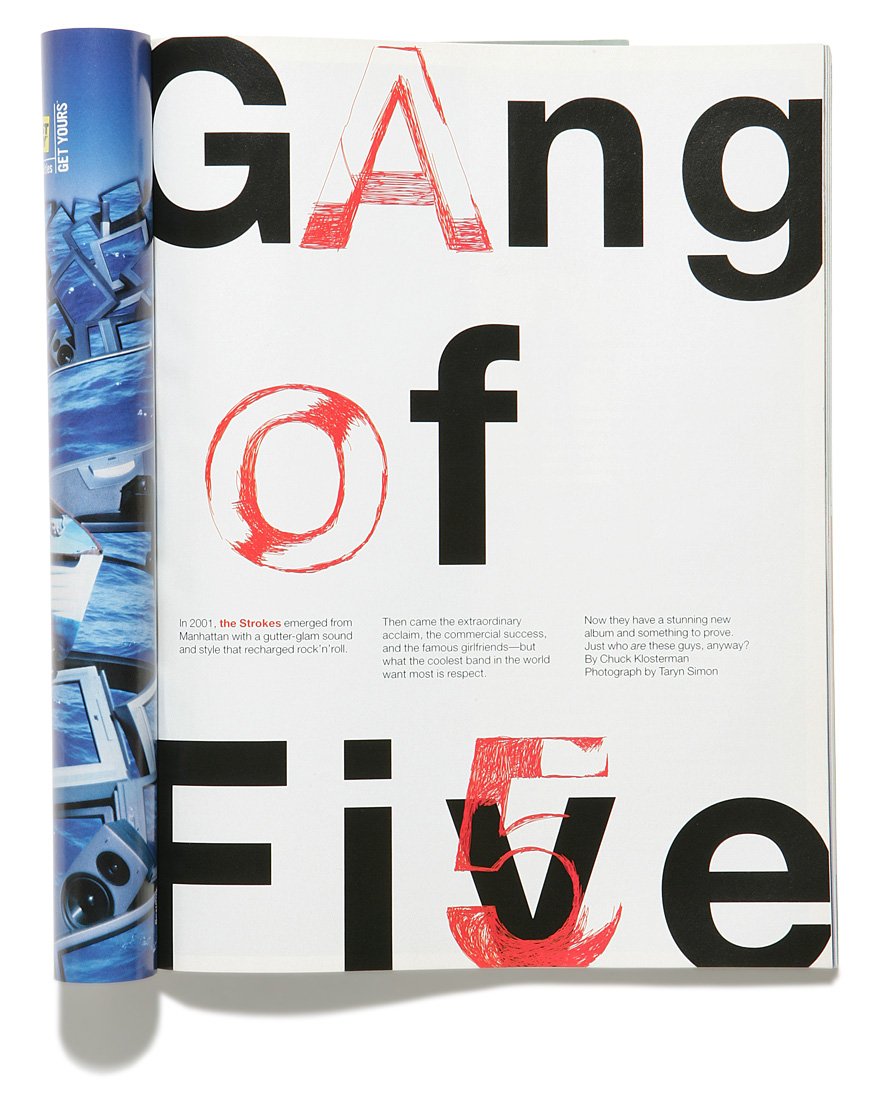

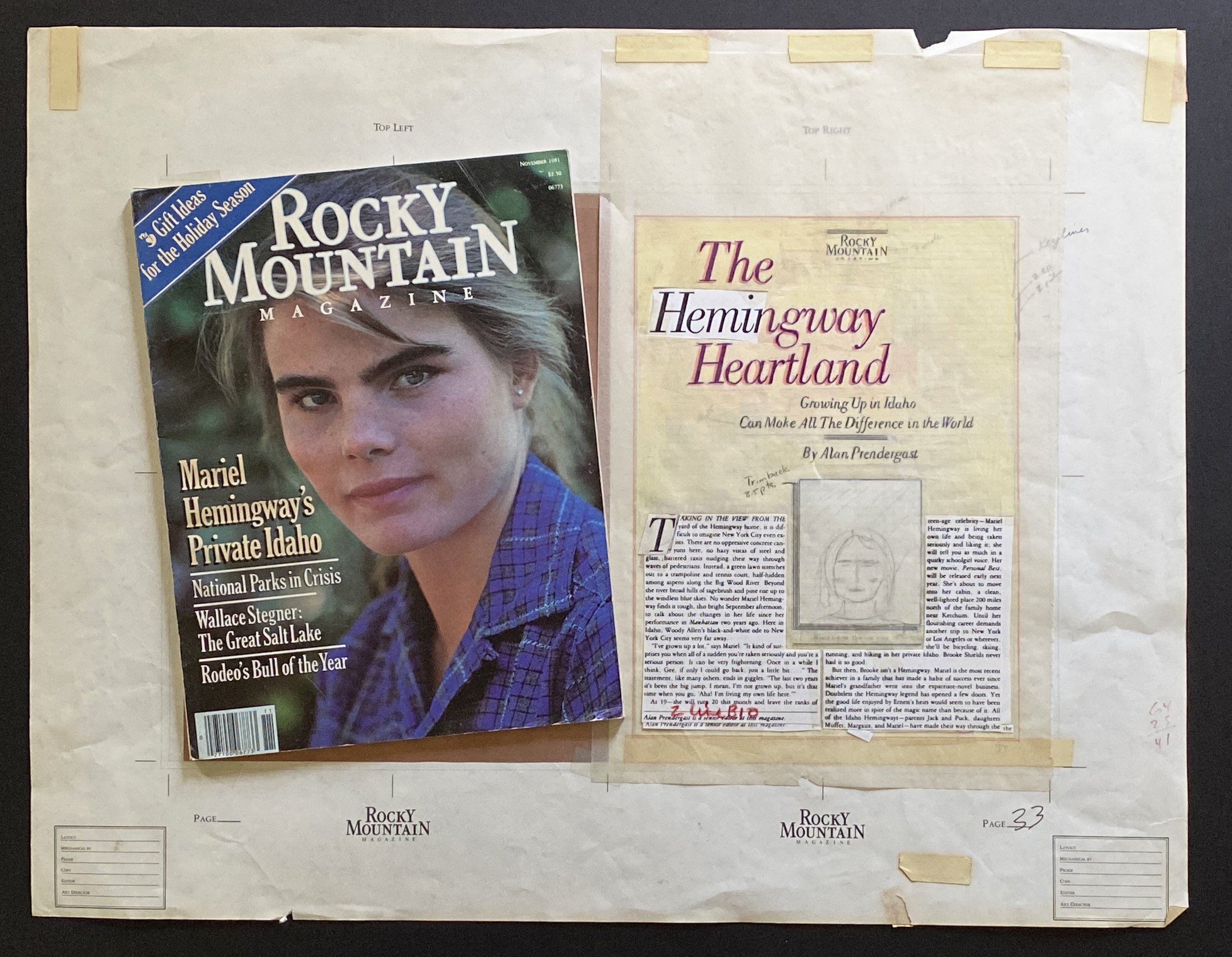

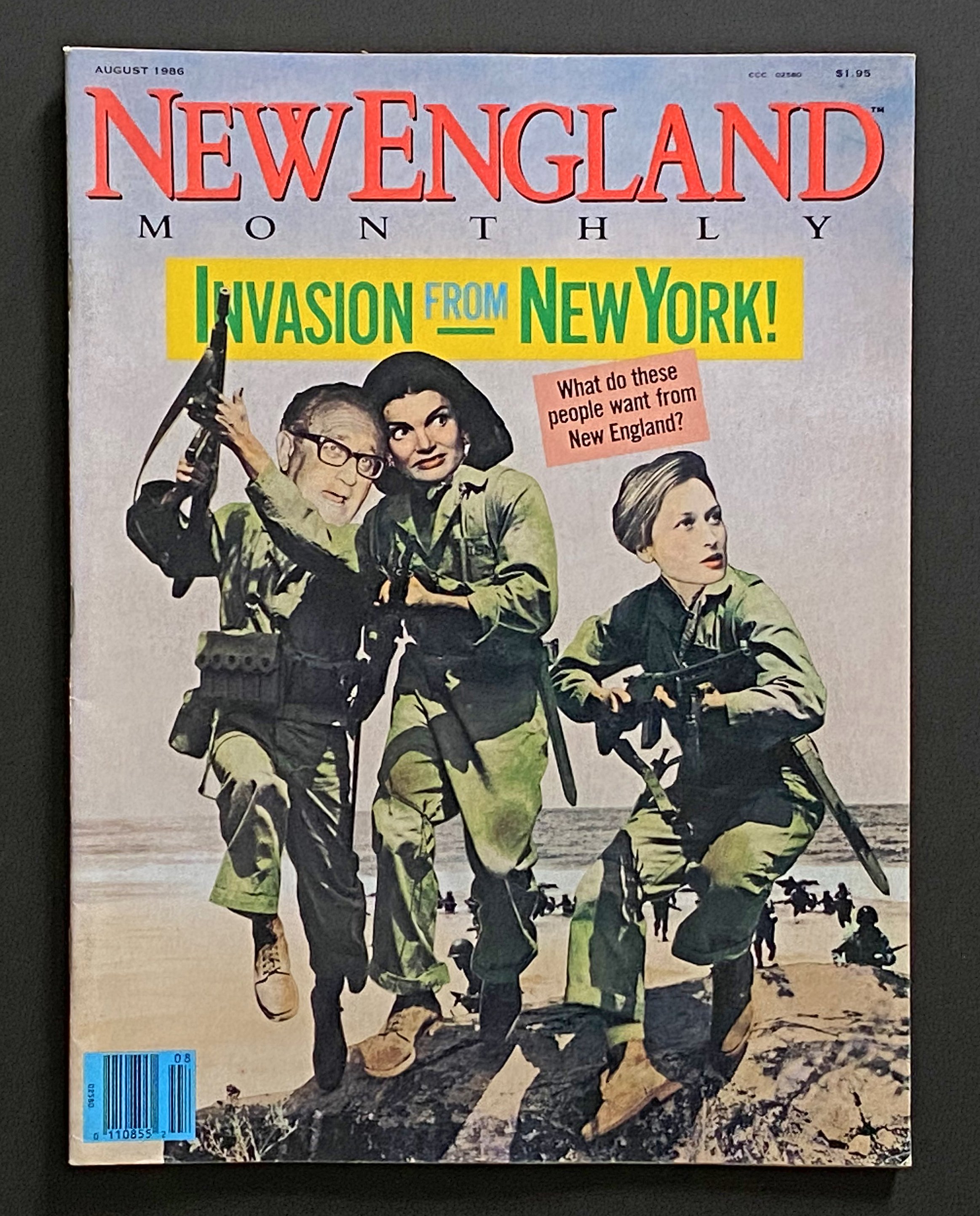

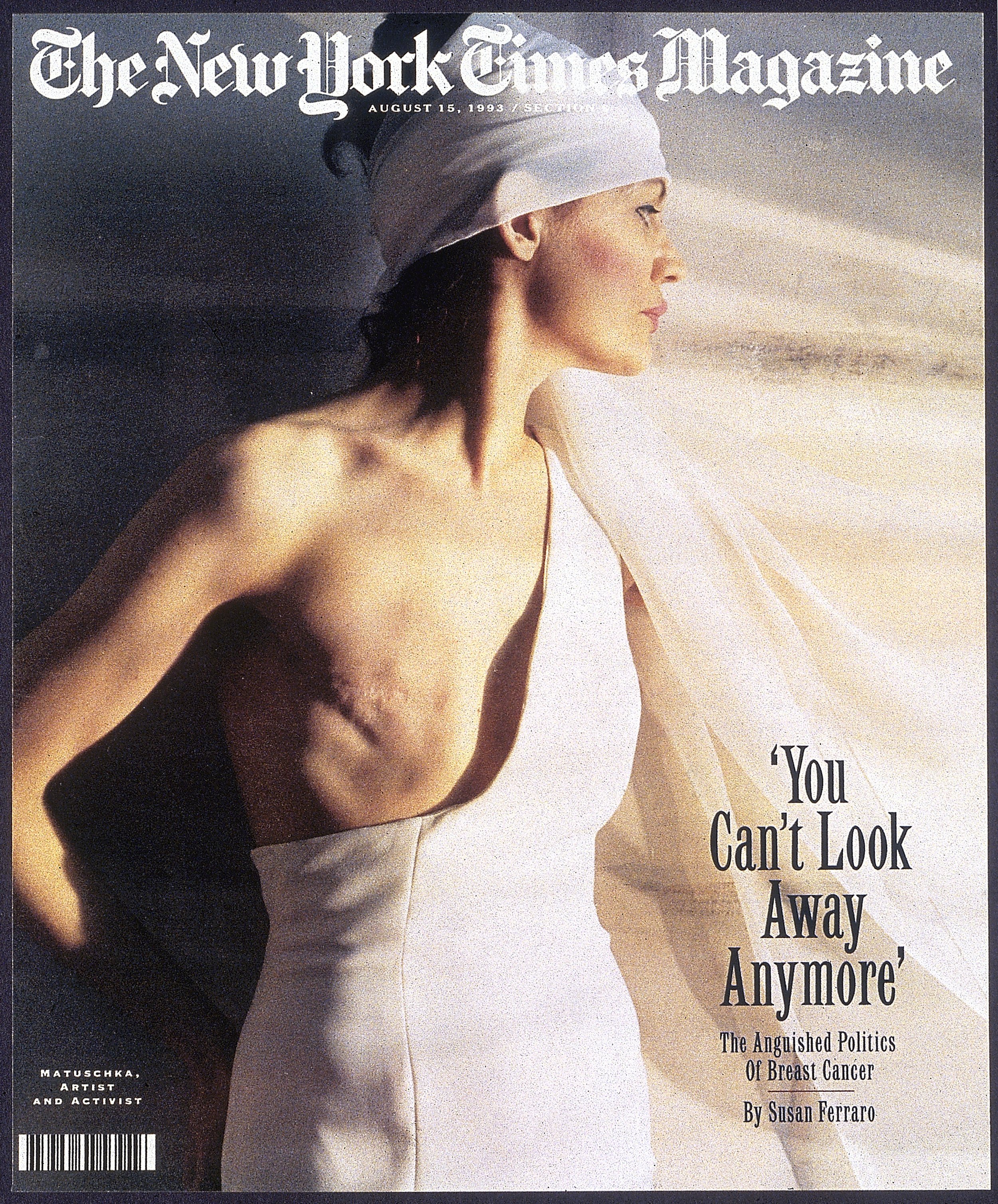

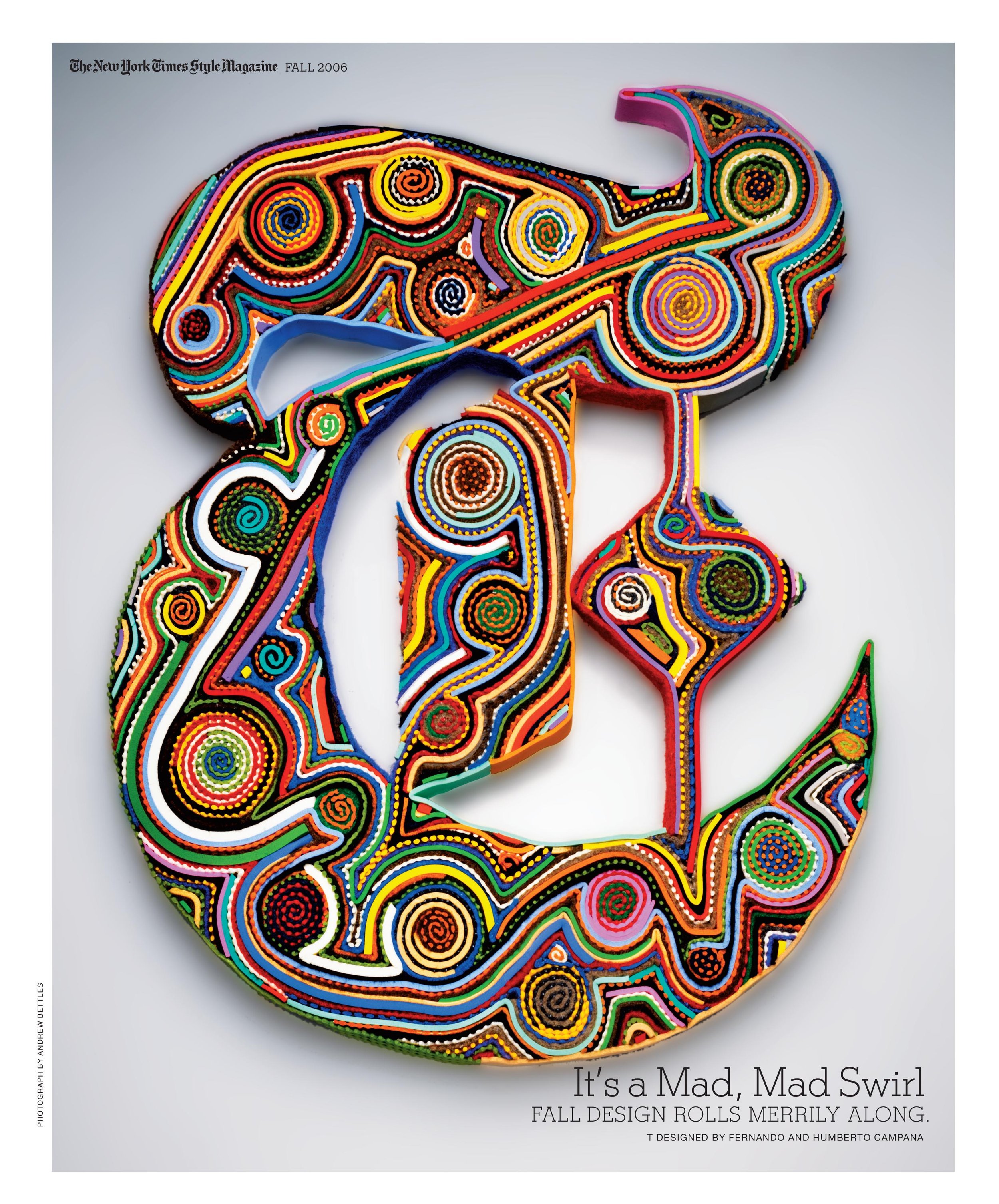

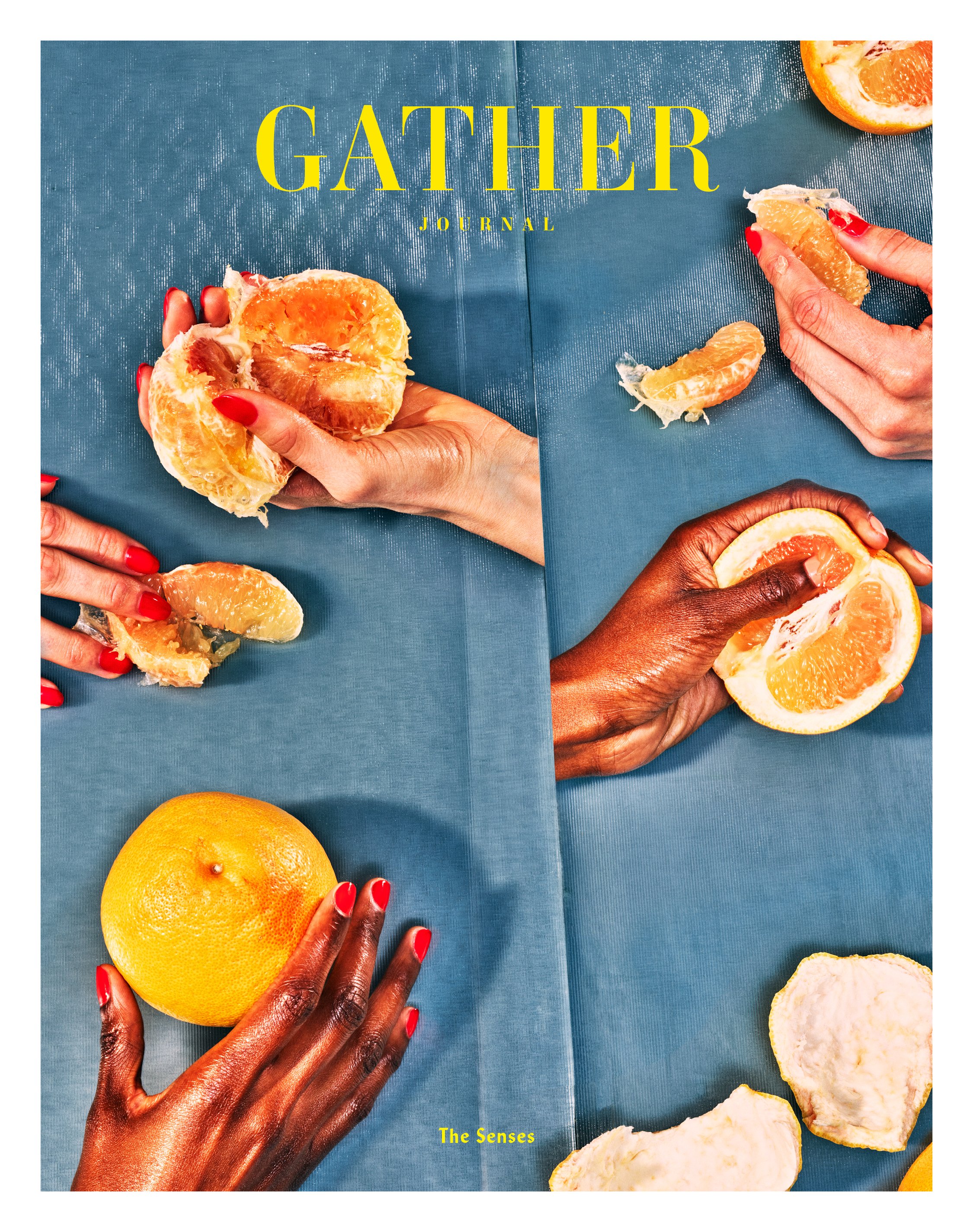

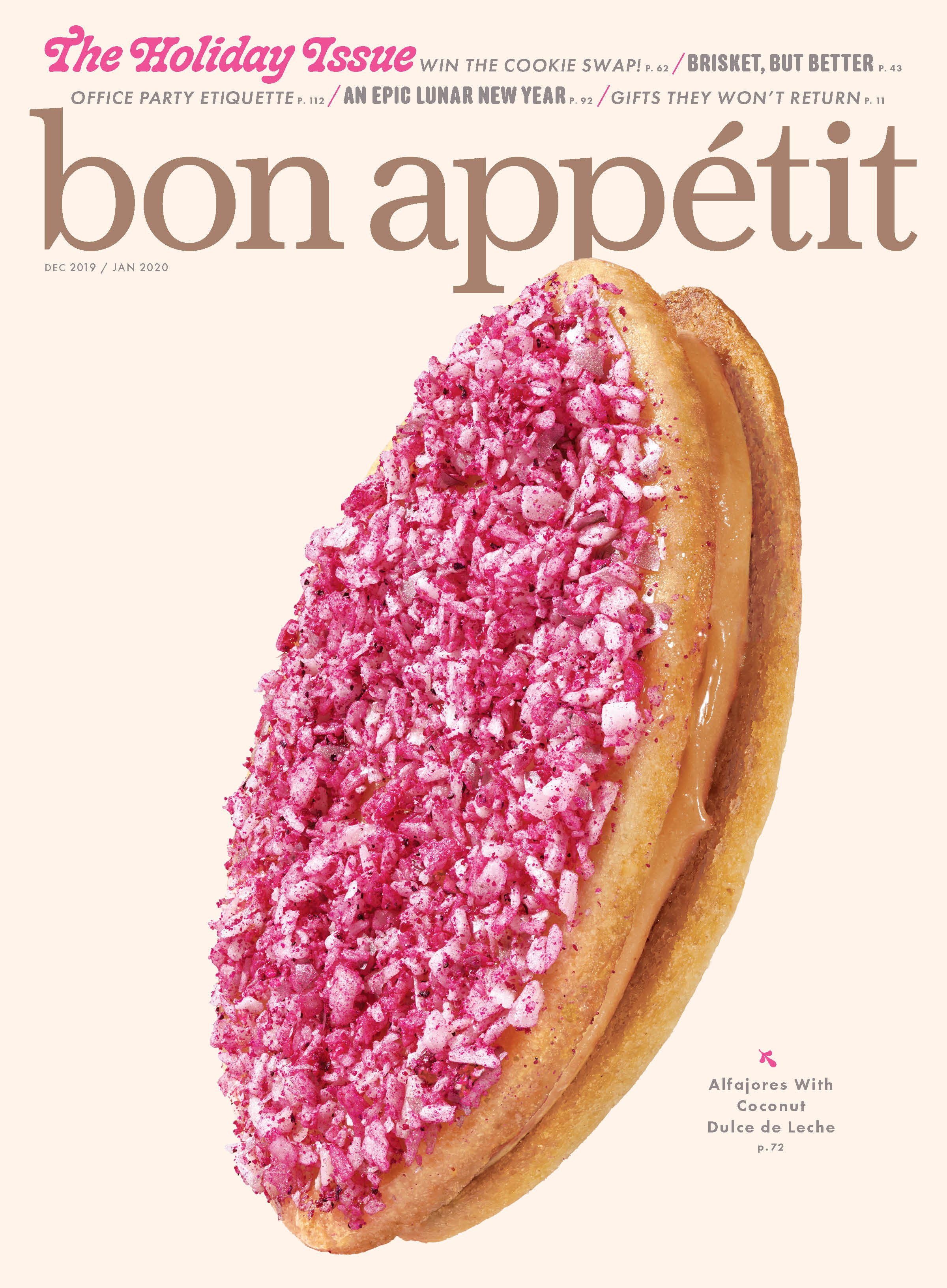

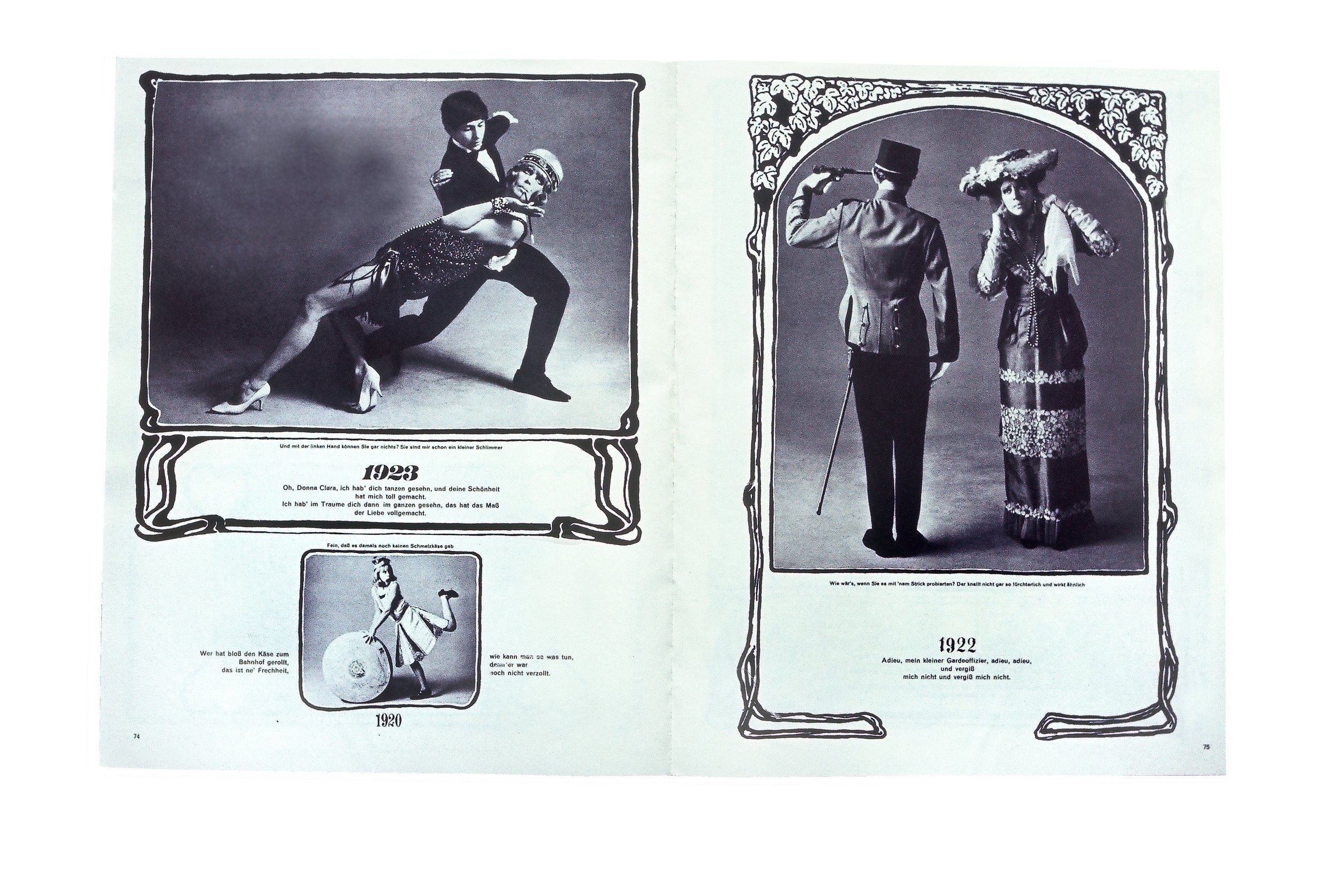

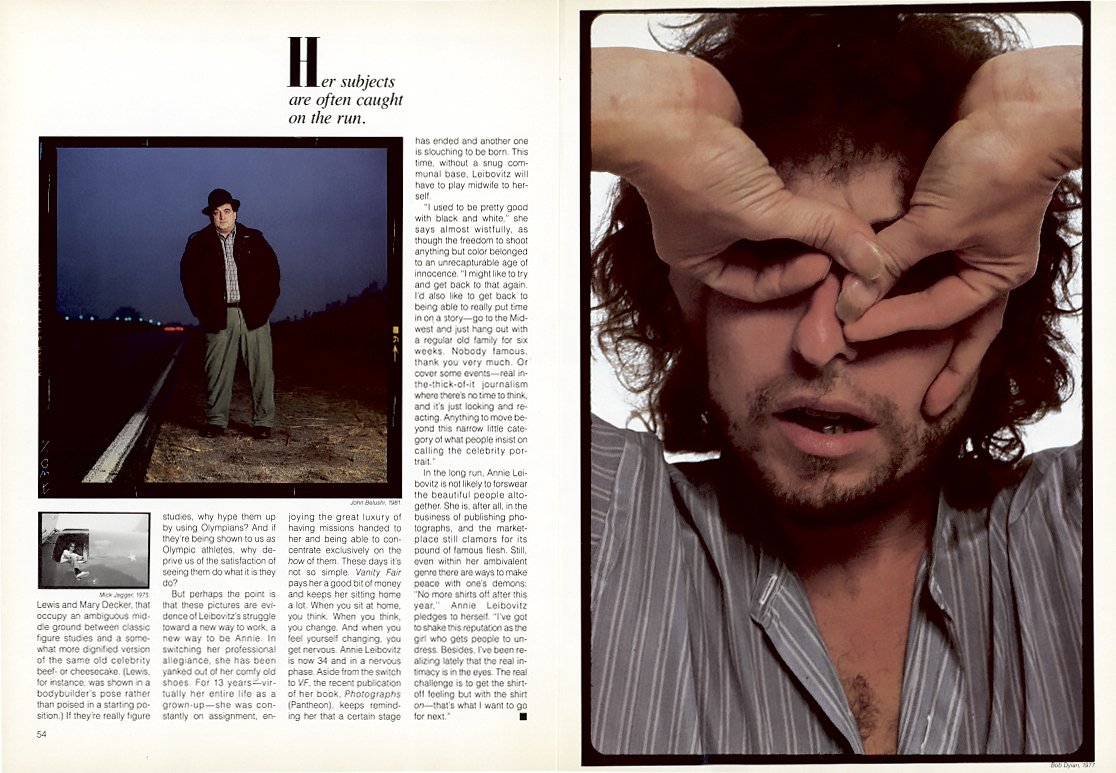

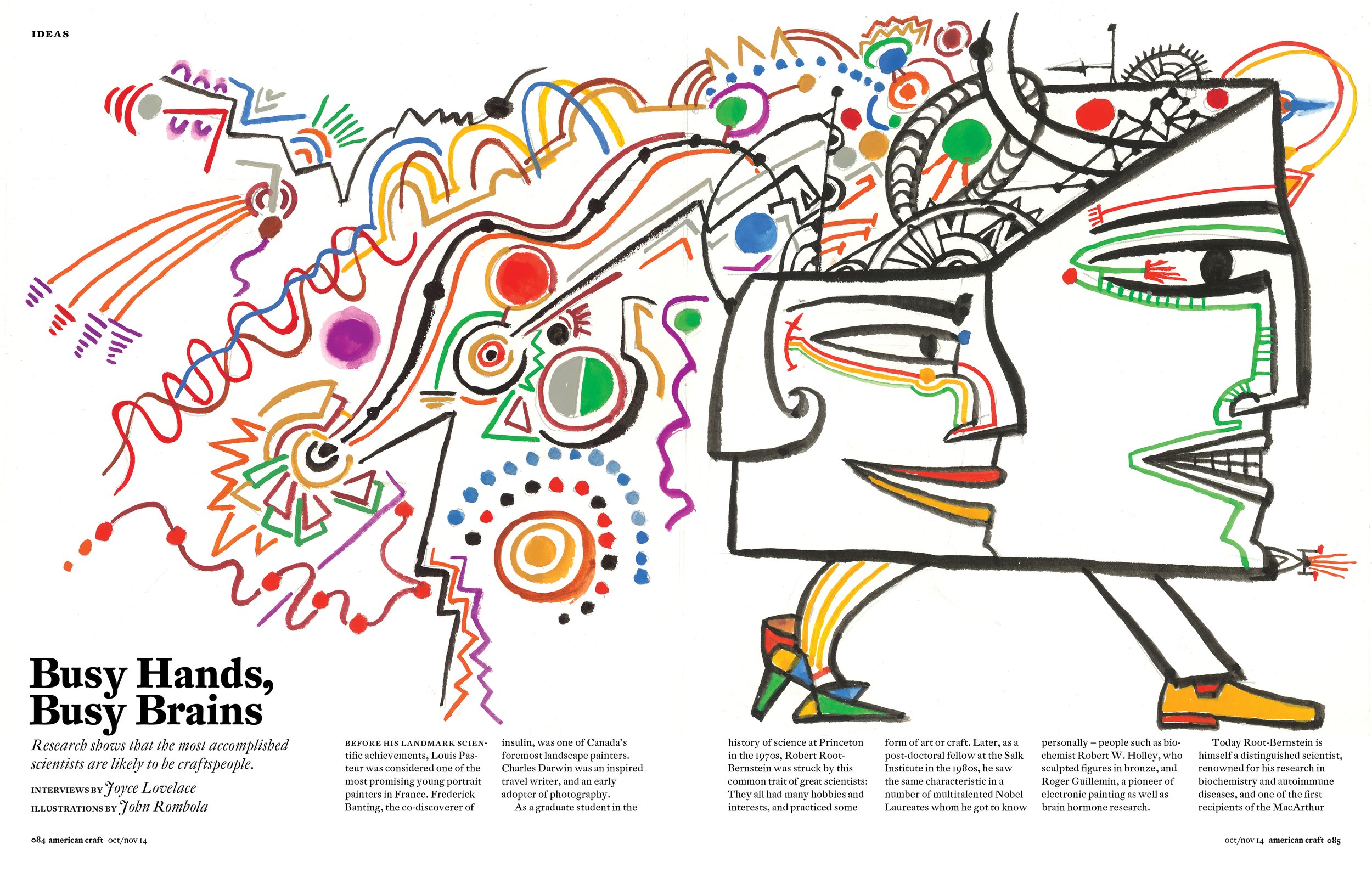

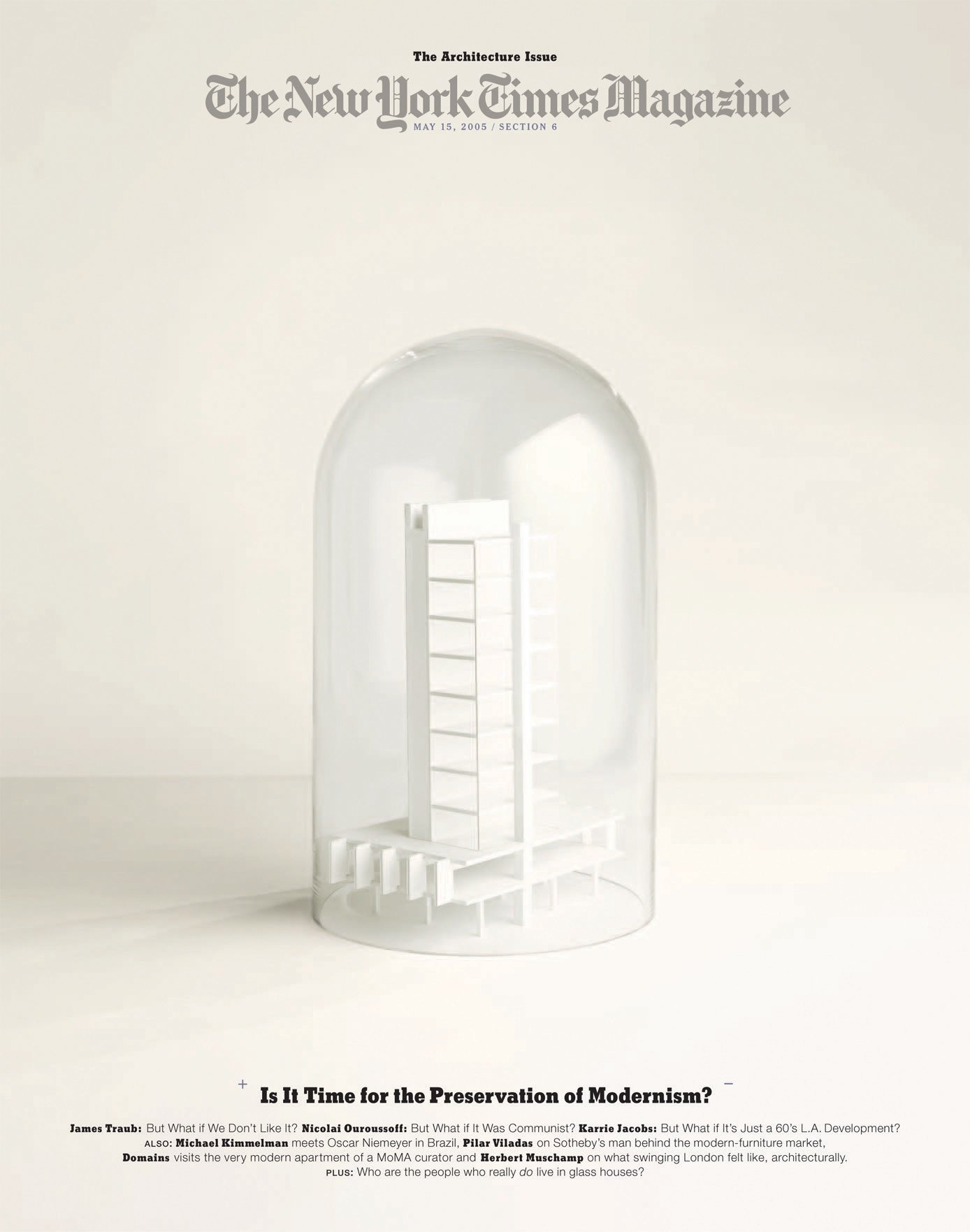

Covers from Dadich’s second tour at Wired, as editor-in-chief

“I went to work on a memo describing a vision that I felt was the right one for Wired and put my hat into the process.”

Patrick Mitchell: So you’ve talked about merging the dotcom back into Wired, but I also remember how you rejiggered the masthead a little bit and suddenly the way the thing was structured was there was a “head of editorial,” a “head of creative,” a “head of digital.” It seemed like some clarity that had been missing for a very long time in terms of how magazines actually got made. They’re just small moves in the sense that you just type things differently, but they were really big moves. And I wonder, as you were making these changes, and incorporating the dotcom, and really re-engineering Wired, in the way that you like to do, how did everybody handle these moves?

Scott Dadich: You would definitely have to ask them because I think not everything goes smoothly or to your best intent or to, to the ideal. But a couple of things were really key. One of them, Howard Mittman, was my first publisher. And Howard and I worked together for years and he was really a great colleague, and a trusted colleague and friend. But Kim Kelleher joined us when Howard moved over. And Kim and I had a very frank conversation in her interview process, and in our very earliest days, about a one-team approach. That yes, we would maintain a rigorous church-and-state system, and that we could do that with a single leadership team.

And I remember a full day of conversation about that. And then a decision that we were going to name those leaders together and that they would co-report to both me and Kim. So we would essentially act as equals in running the system and that we would have our lanes certainly. But....

Patrick Mitchell: Kim was the publisher?

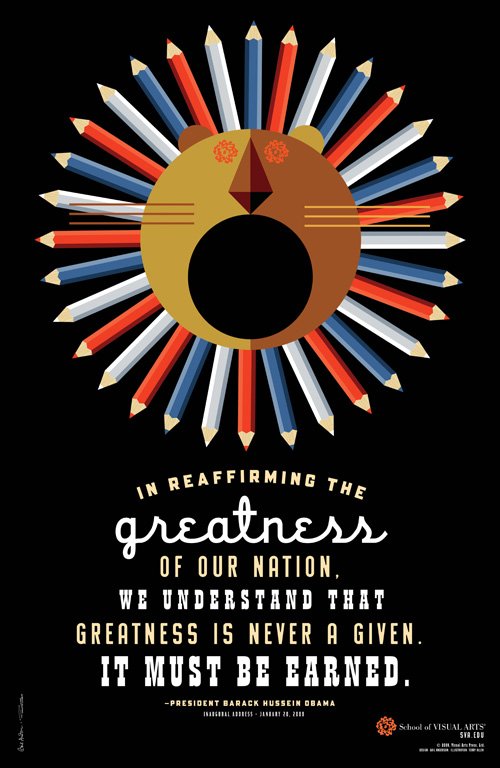

Scott Dadich: …Kim was the publisher and chief revenue officer. I think that was the title at the time. But that was new also. And I think because we were able to do that at the very top, it set a kind of tone around where we were going and the kind of rigor with which we wanted to run the organization, that it is a business and we needed to have an awareness of the fundamentals of how that business was doing in order to protect the journalism, and to invest in it, and to take the big swings that we wanted to take, whether that was putting Edward Snowden hugging an American flag on the cover or spending almost a year to convince President Obama to guest-edit. And it was because we had those systems in place that we could take those much bigger swings with the editorial.

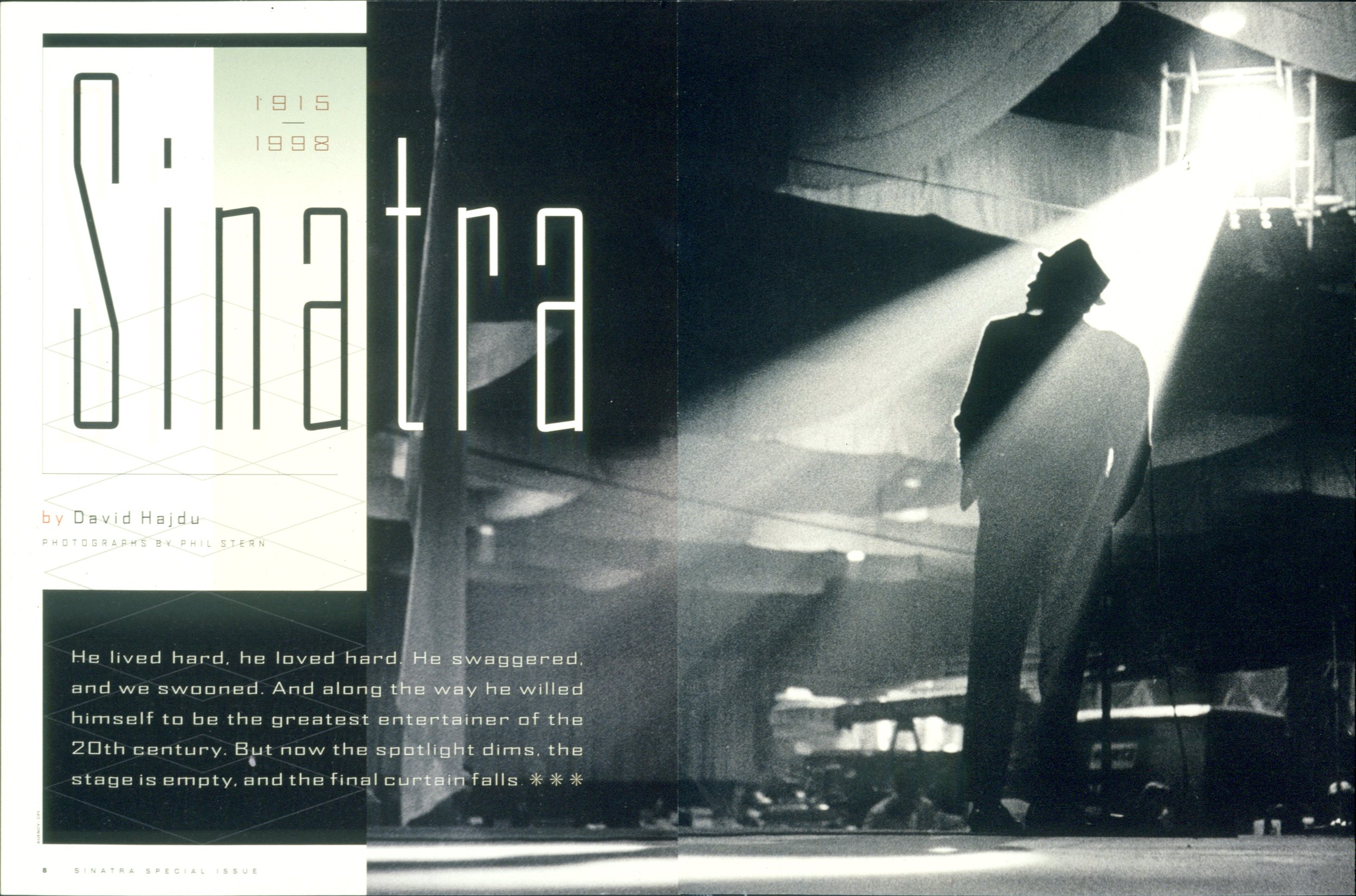

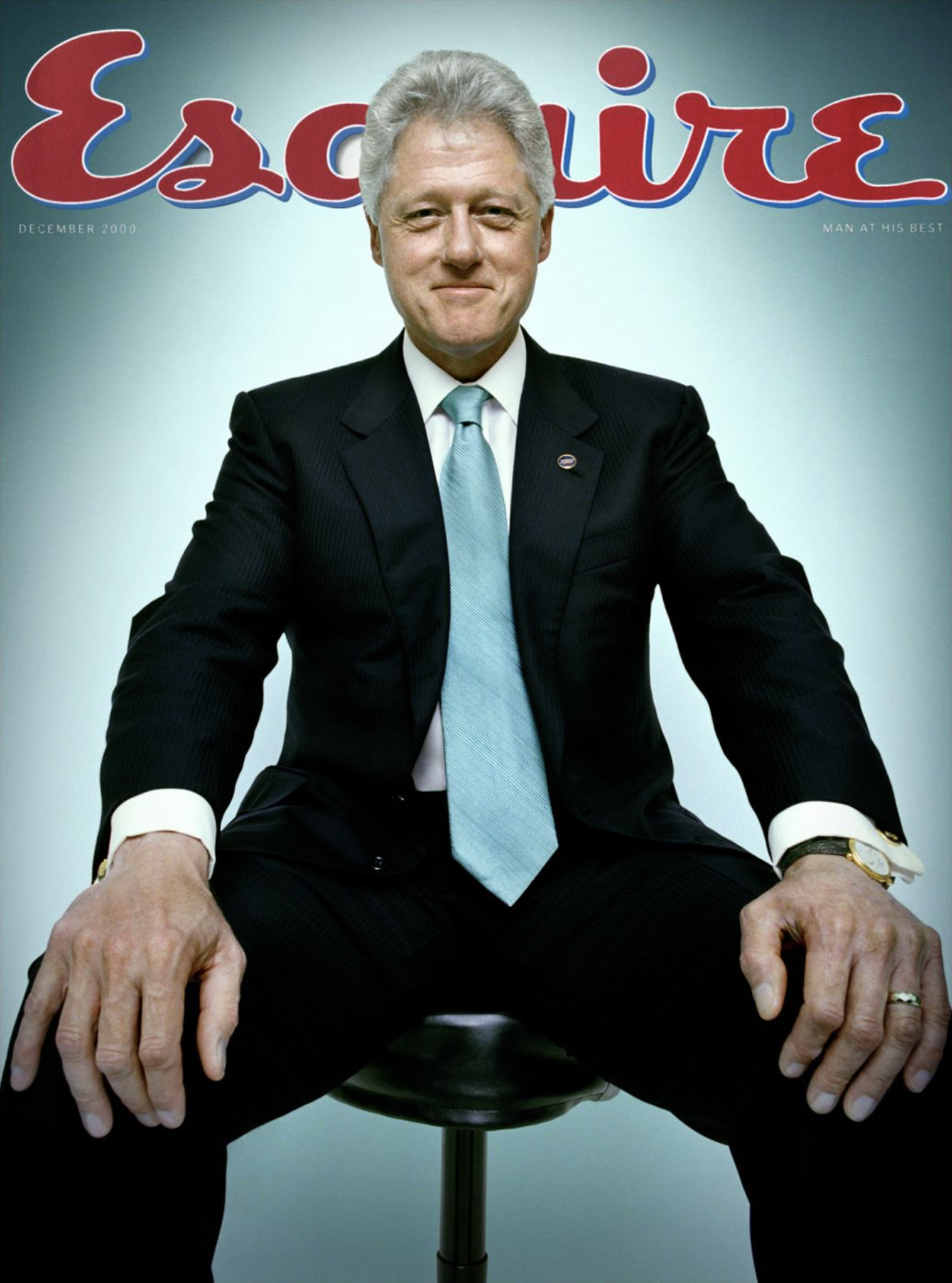

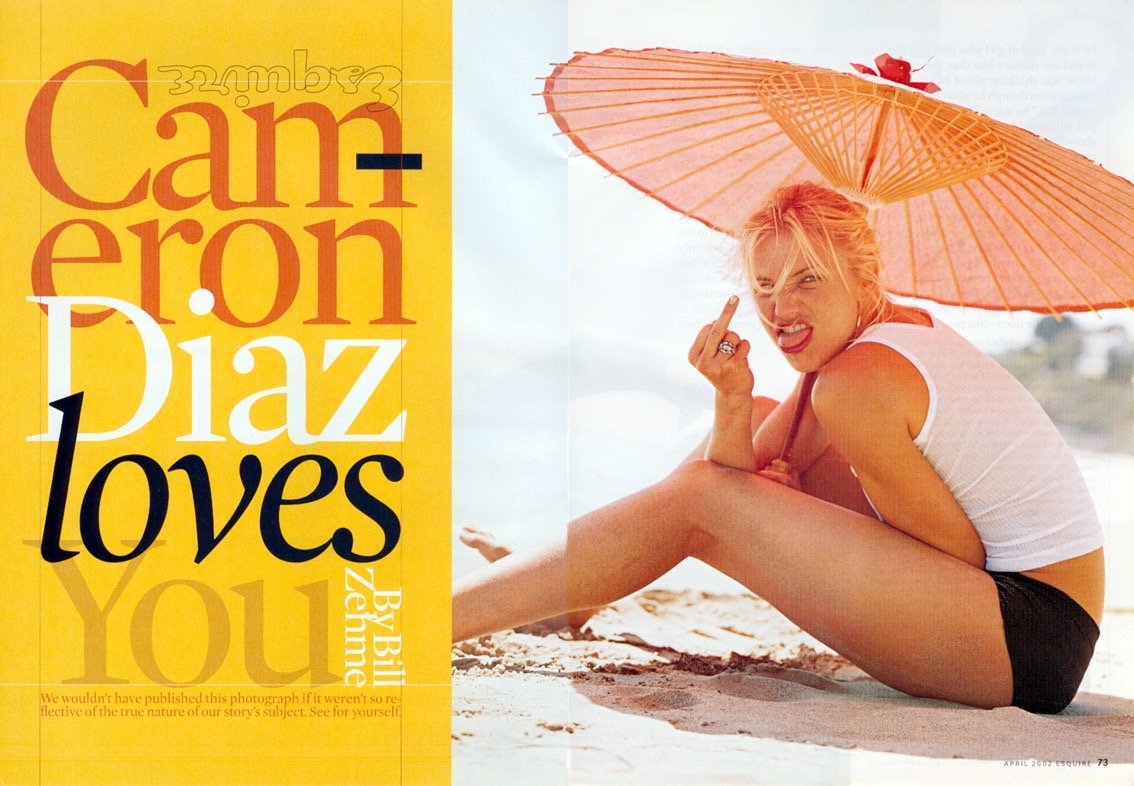

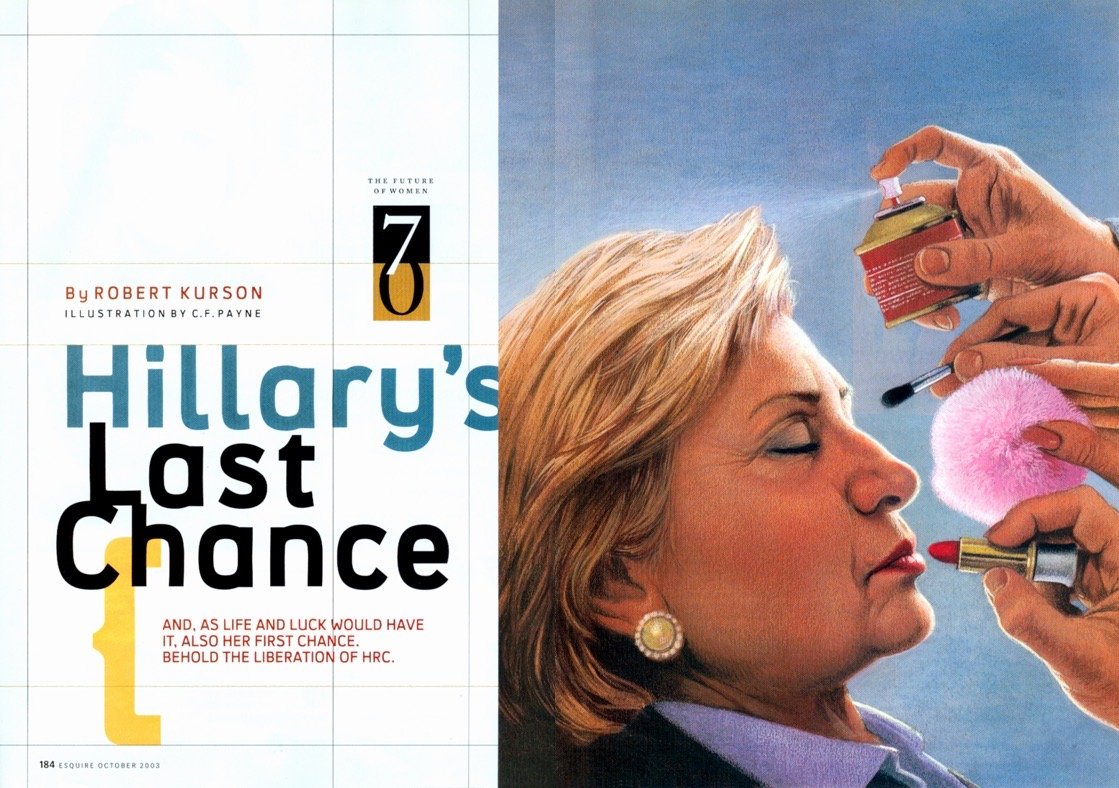

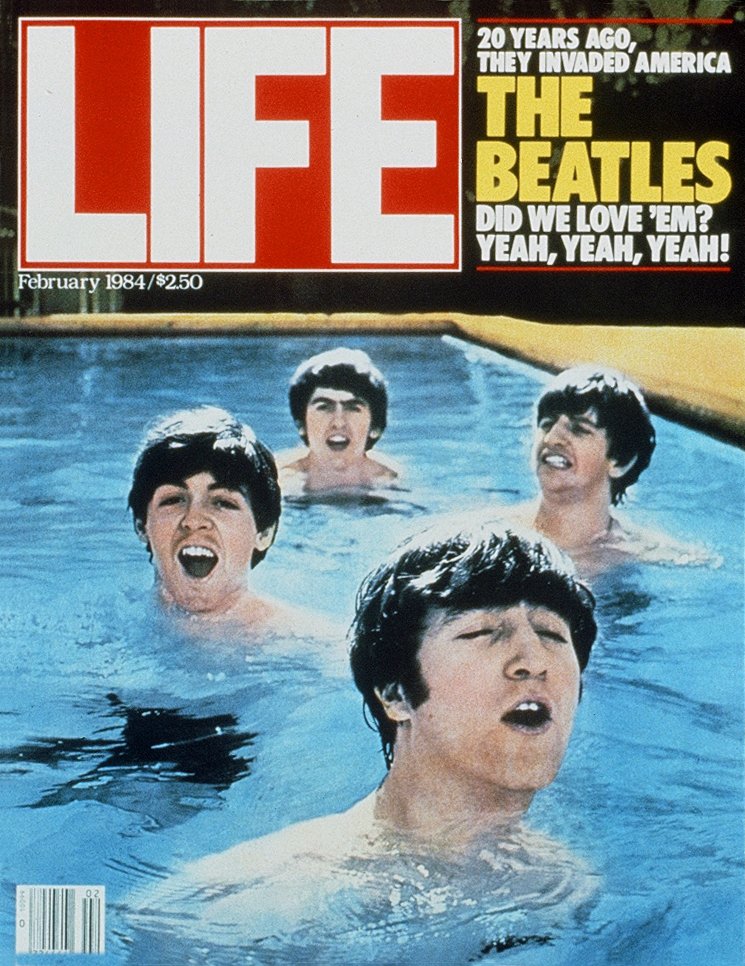

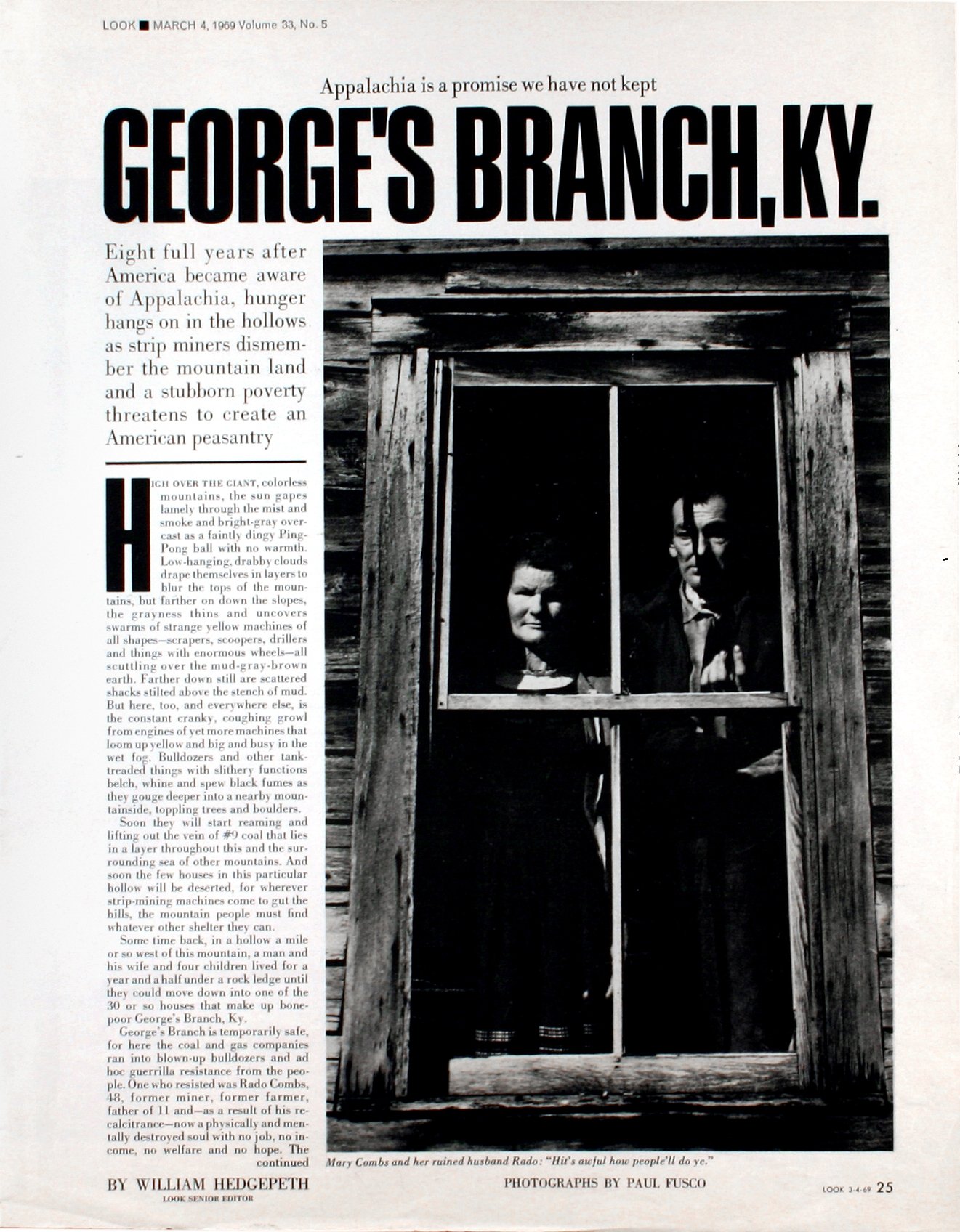

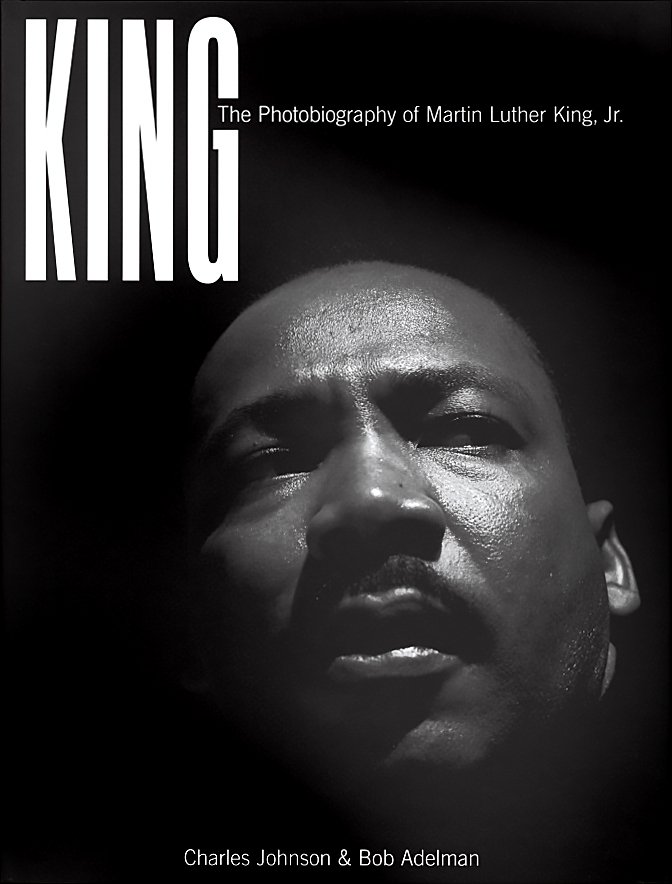

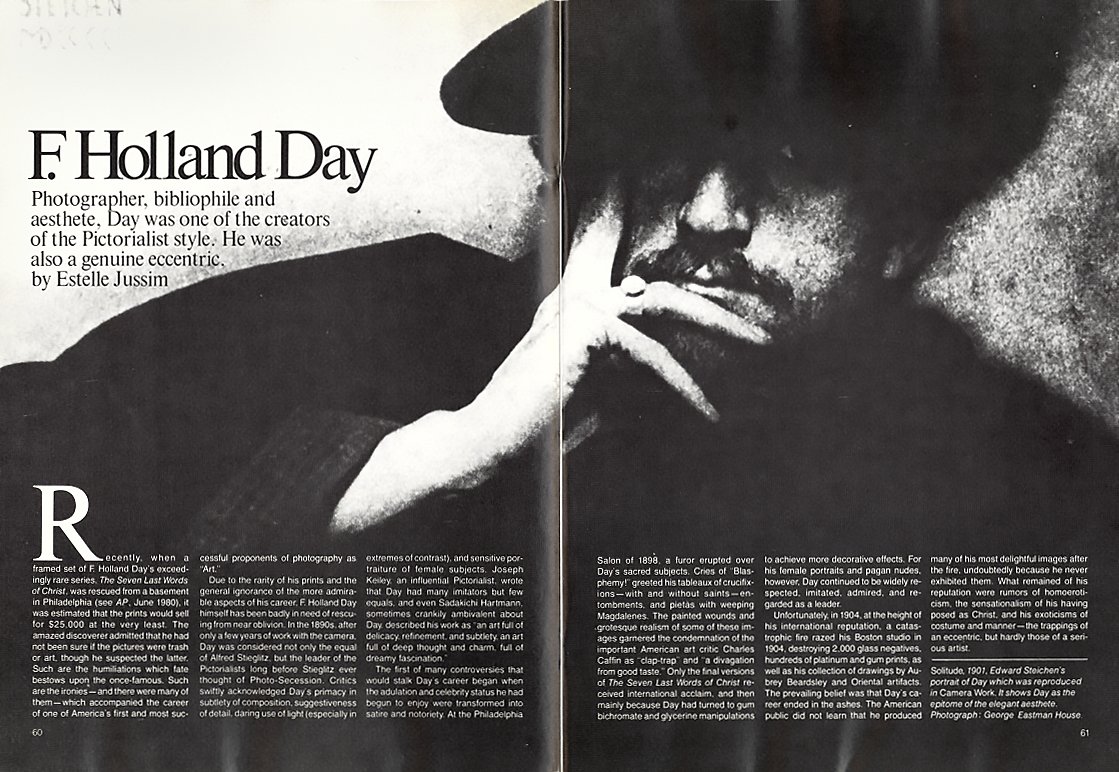

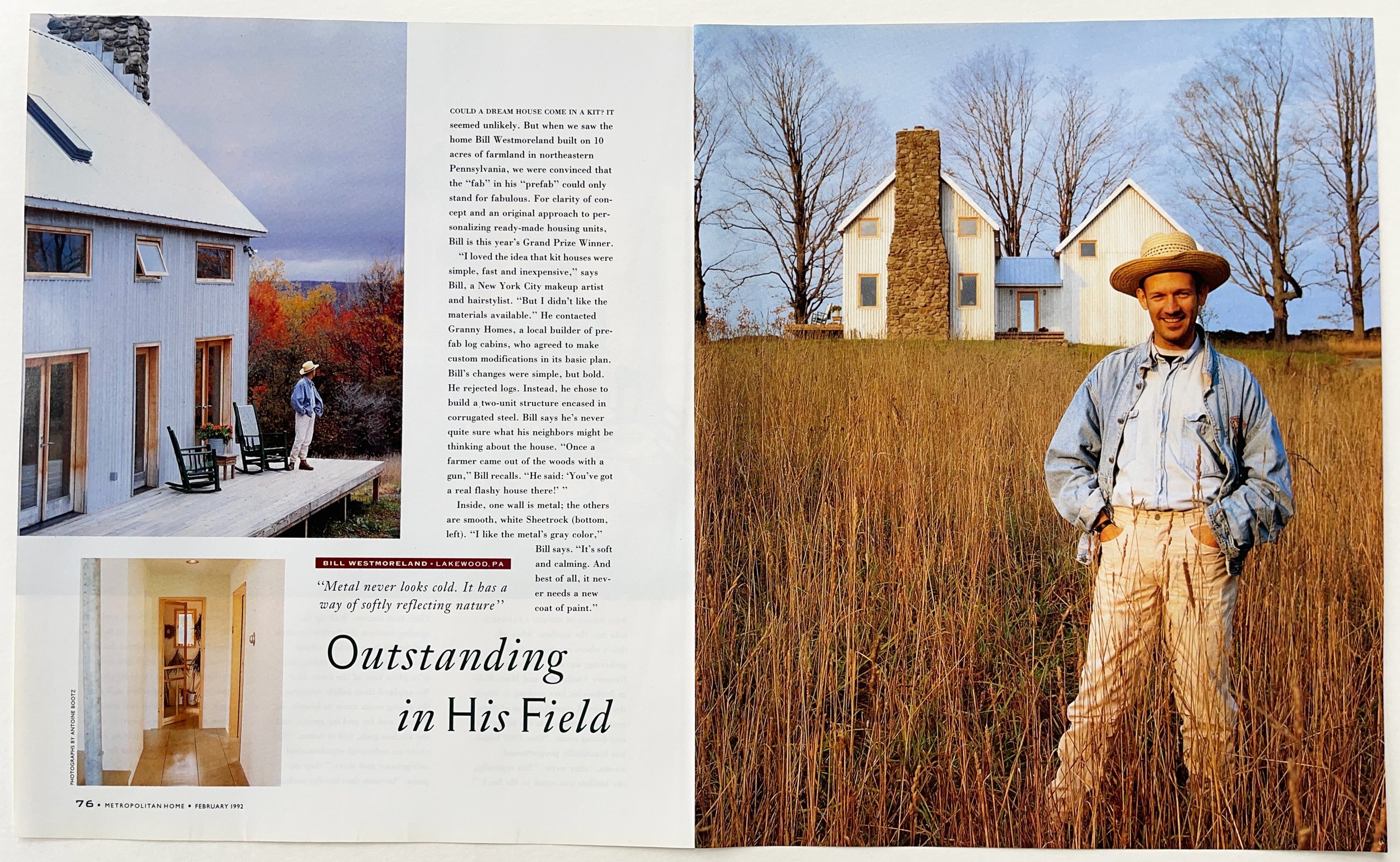

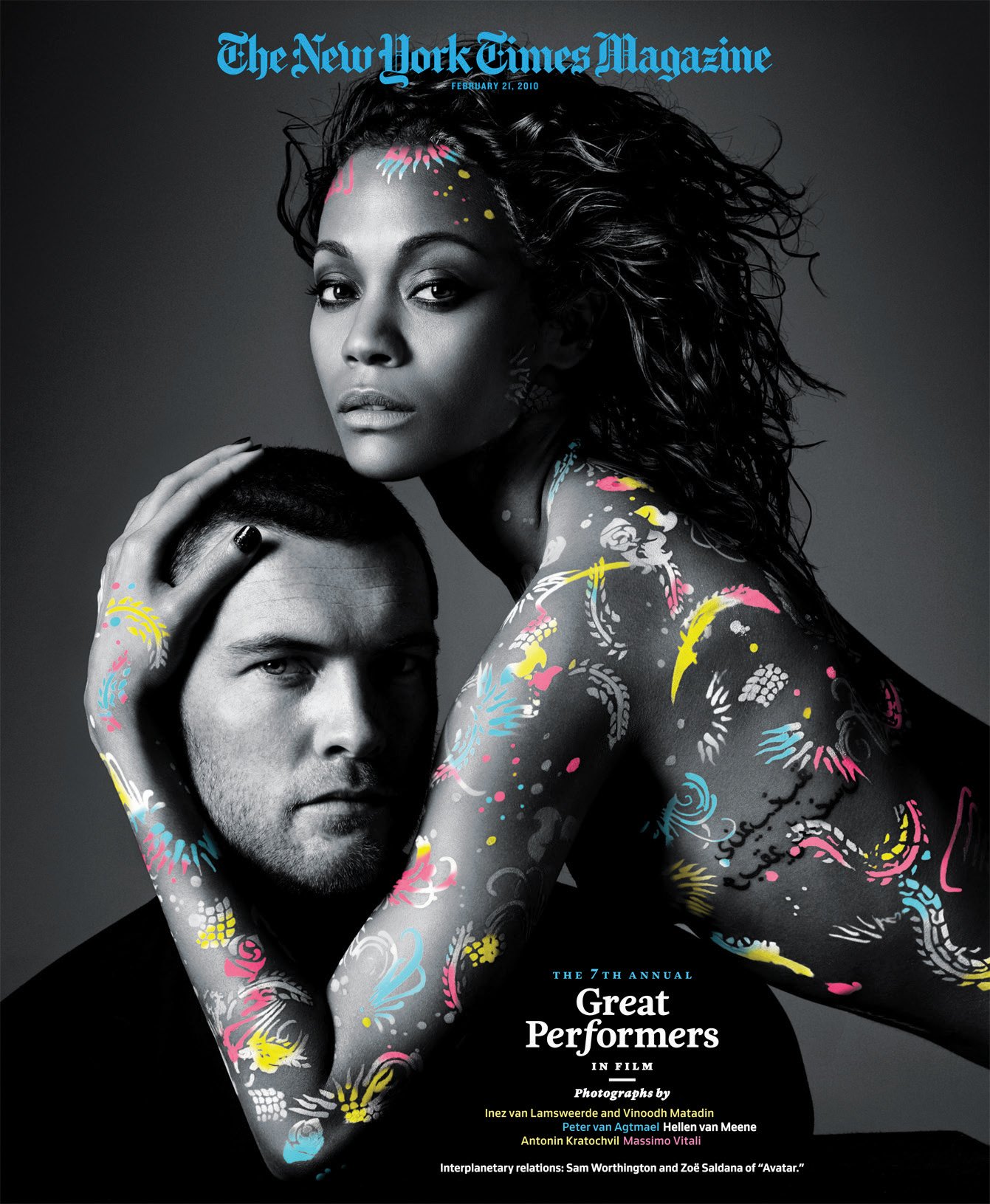

Dadich (center) with Joi Ito and President Barack Obama in the Roosevelt Room of the White House on August 24, 2016.

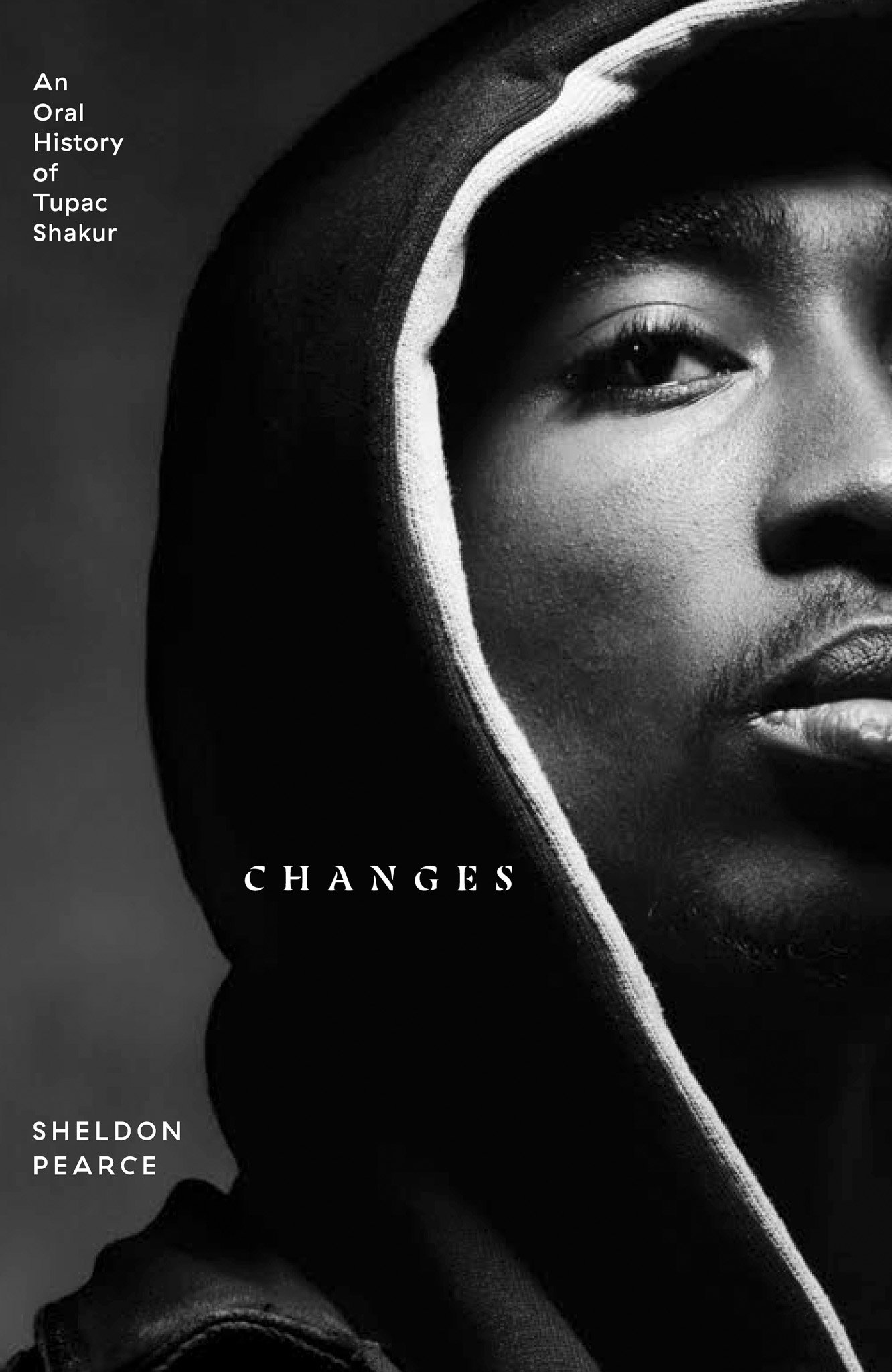

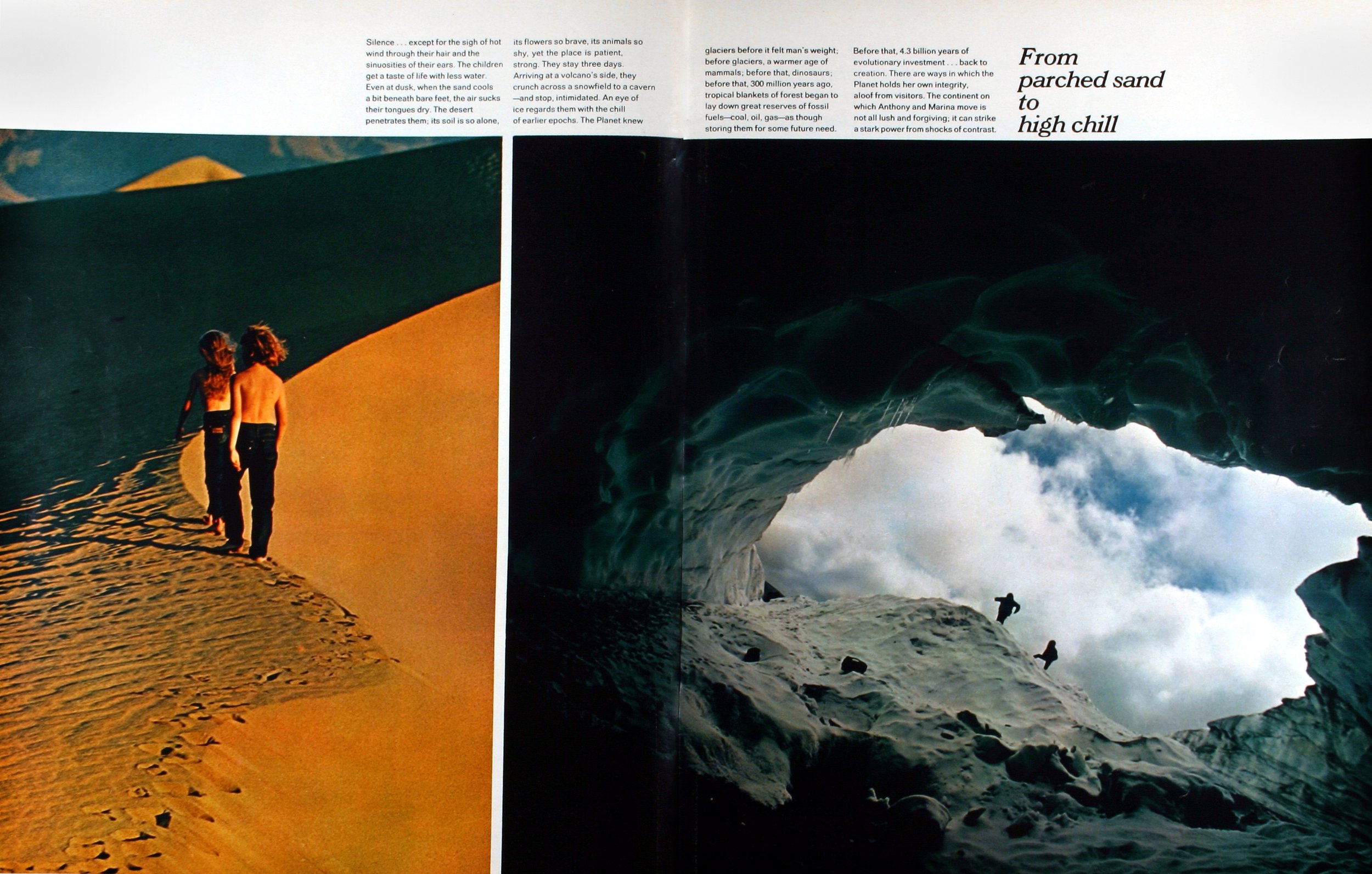

Patrick Mitchell: You had some incredibly amazing editorial highlights in your time there, the Edward Snowden in Moscow, your big-name guest editors: JJ Abrams, Christopher Nolan, Bill Gates, Serena Williams, President Obama. Can you tell our listeners, a) how those guest-editorships worked from the first ask, and b) how that process went with our former president?

Scott Dadich: Sure. The guest-editorships, I think were one of my favorite parts of Wired. To some degree, certain guest-editors did more than others. But I was really lucky in that we had really involved guest editors and it became, I think, a highlight of the year when we got to do that.

The Obama issue was—you talk about relationships and being in person and fostering conversation—that really came from a really random moment, actually back to Austin being at SXSW, as we would always go, and running into a buddy of mine who had been doing some consulting with the White House, and his very dear friend had become the chief digital officer of the White House.

And we just went and we’re having margaritas one night and I said, “We should do something with the president.” We’d been trying to get him into the pages of Wired for a long time. And this guy, Jason Goldman said, “Pitch me some ideas.”

And so I wrote a memo, and included everything from The Wired Interview to a feature story—and we were talking a lot about AI at the moment—to all the way to the president should guest-edit an issue. And Jason brought us out to the White House that spring.

And I remember sitting with Jen Psaki just outside of the situation room, and it was me, and Caitlin Roper, and Adam Rogers, and Rob Capps. And we made our pitch. And Jen really got it and she said, “I think this would be amazing. I think the president would love to do this. Send me some more documentation and let’s talk about what the process would be.”

Obviously he’s got a day job, so he’s not going to be wandering around the Wired newsroom, but if we can engineer something where he can have his fingerprints on this—and he will have thoughts. He’s a great editor, obviously a great writer. He’s going to mark things up and he’s going to give notes on things. And if you’d be willing to engage us on that.

We also put in some guidelines and frameworks, but we agreed to it that spring and then spent the better part of the summer working with the team at the White House and then getting notes back from the president about story selection and edits and he killed a few things.

And we had engineered a moment in August of that year of 2016 where we’d be together. Do the interview, do the photoshoot, really spend the better part of a day together, looking at all this work and talking about it. And that remains one of the great highlights of my career to be able to do that. That was just a day I will always hold very dear in my heart.

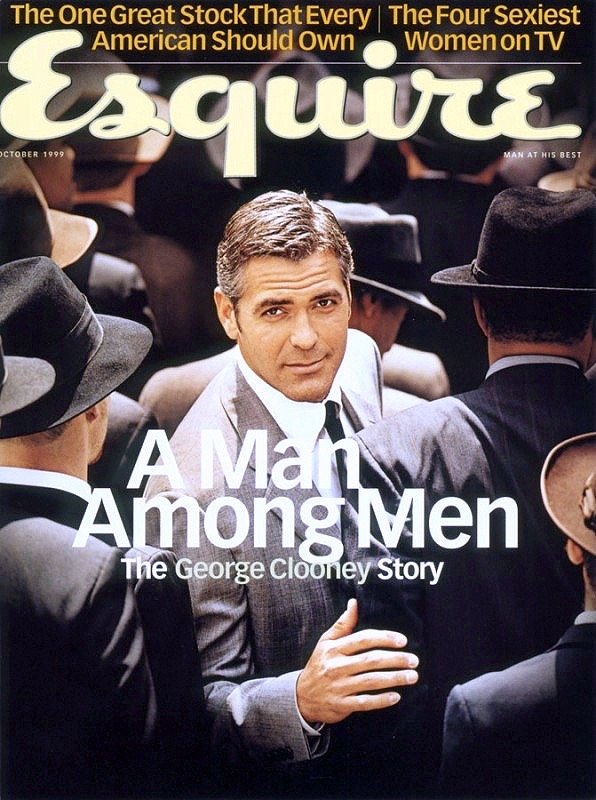

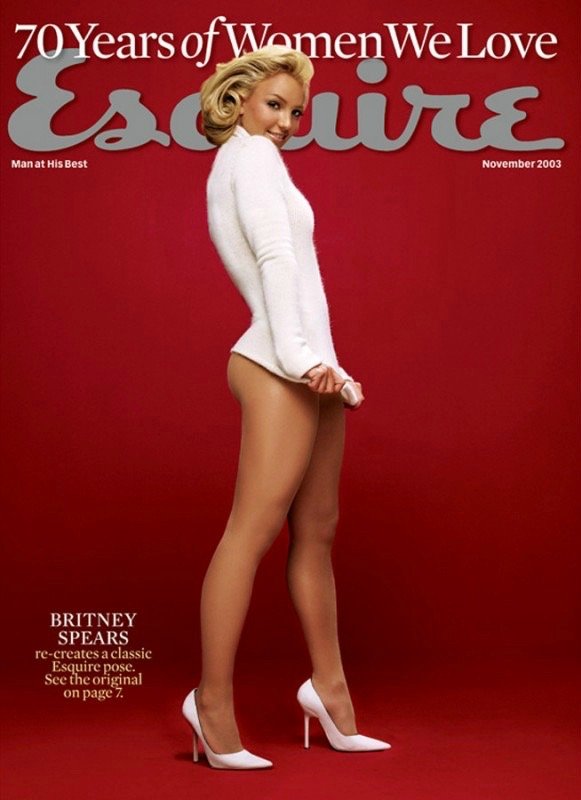

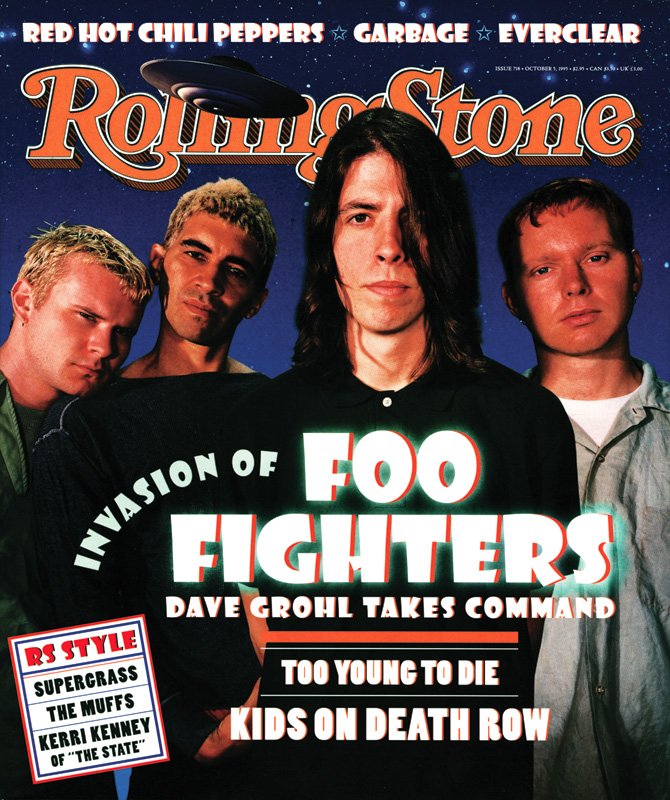

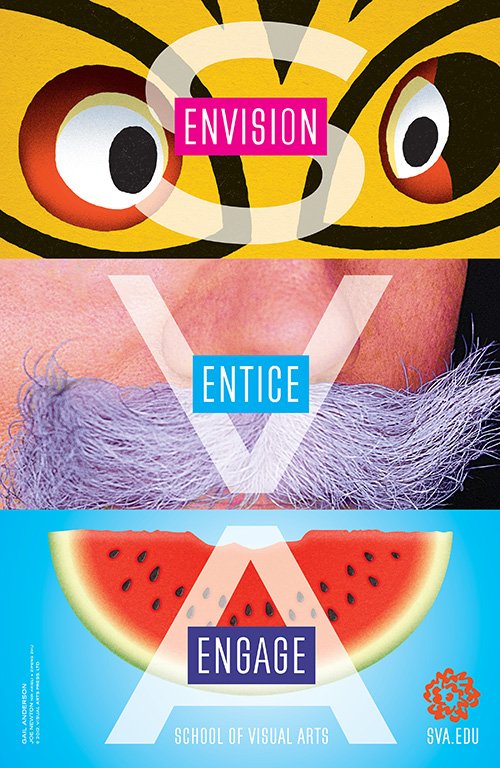

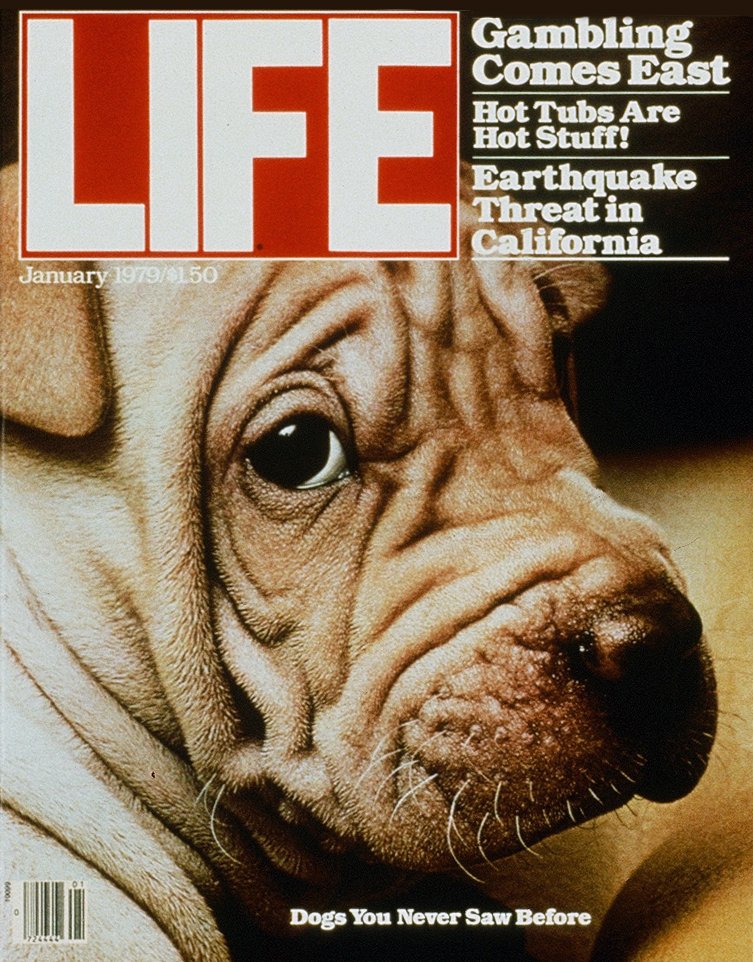

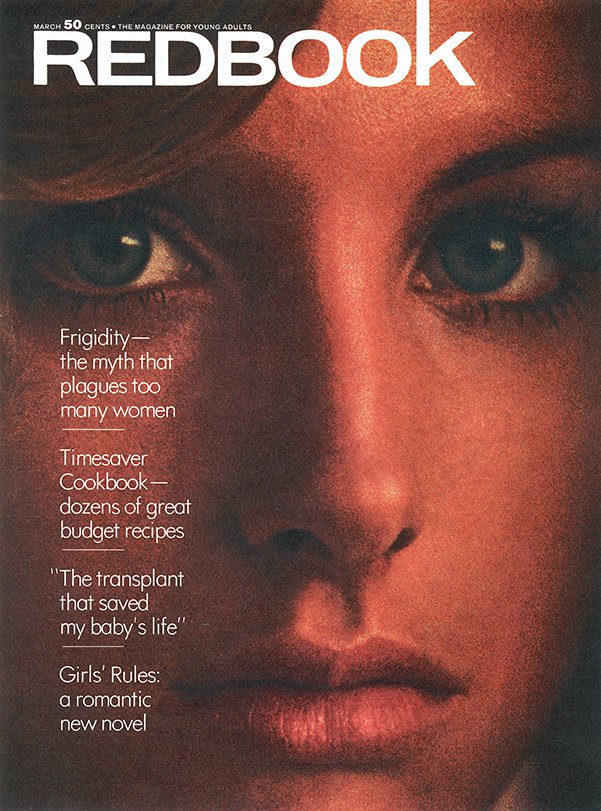

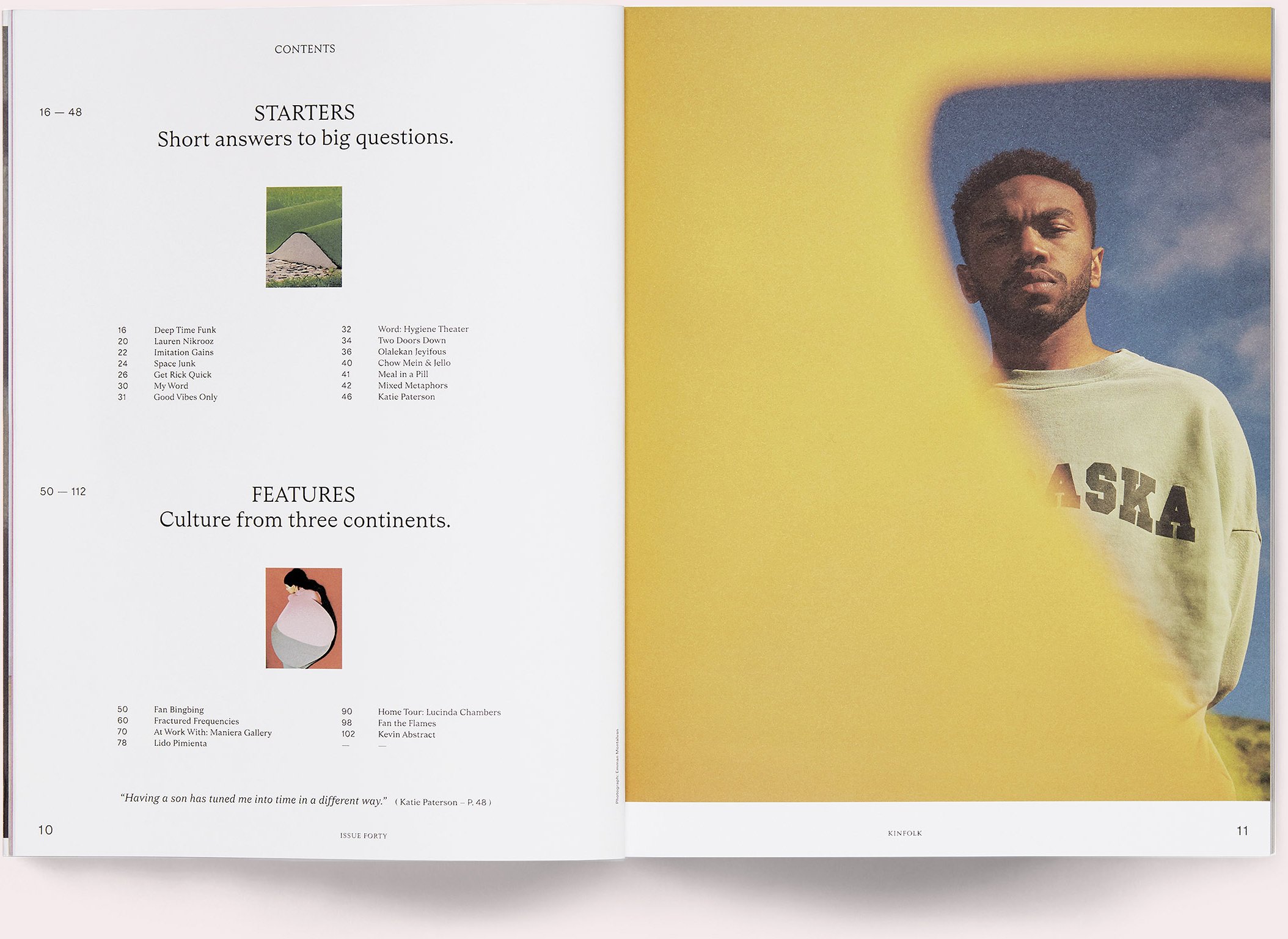

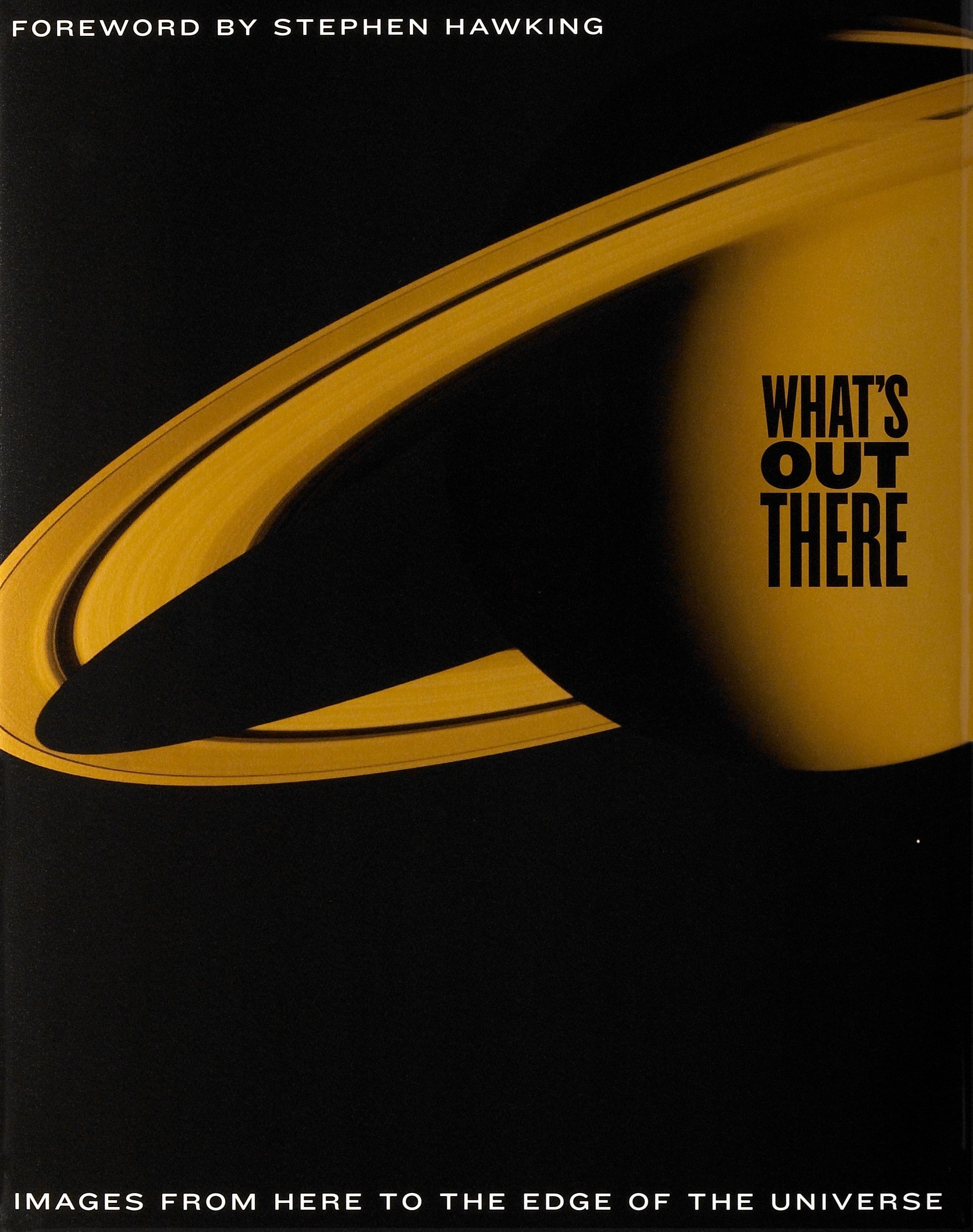

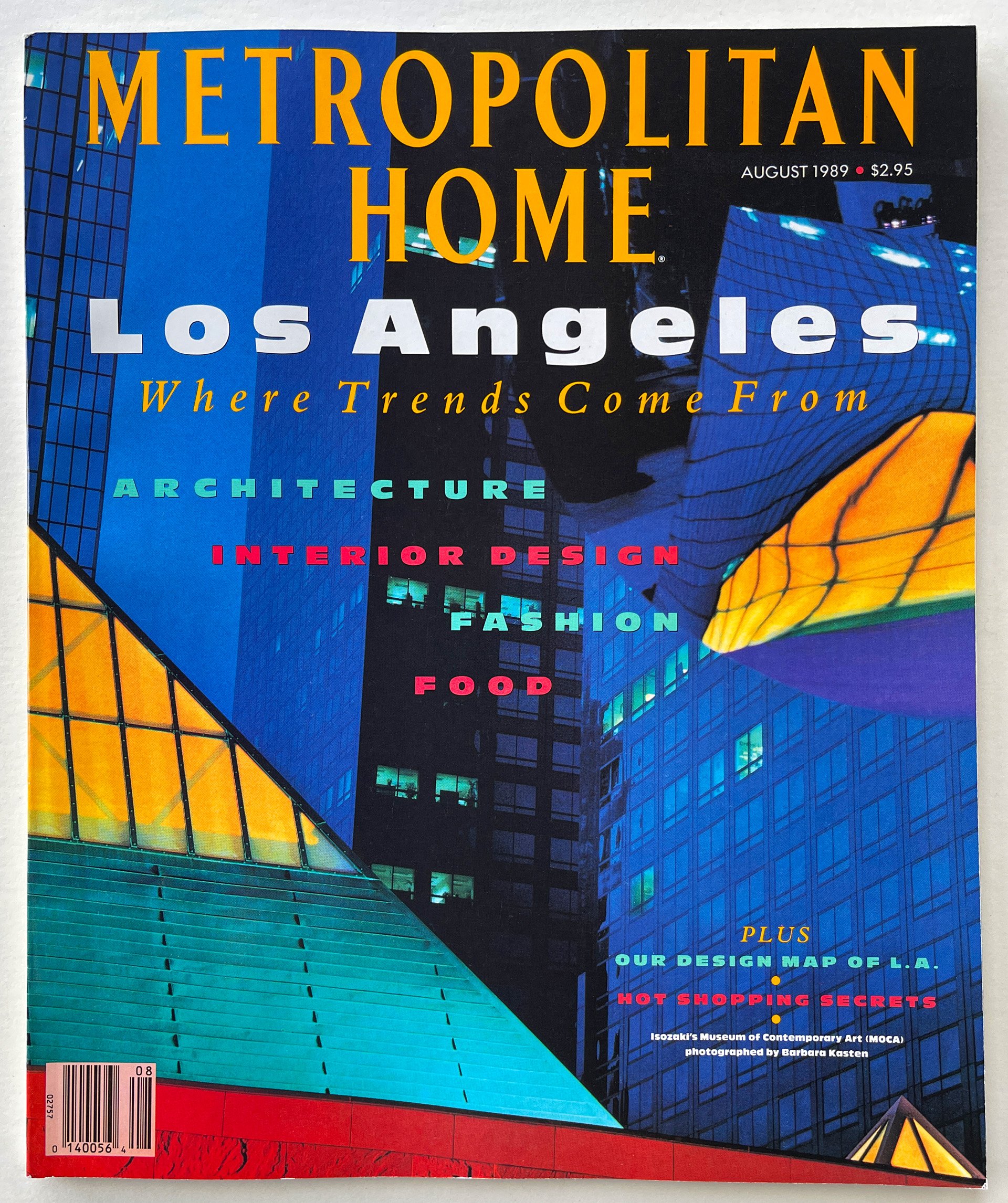

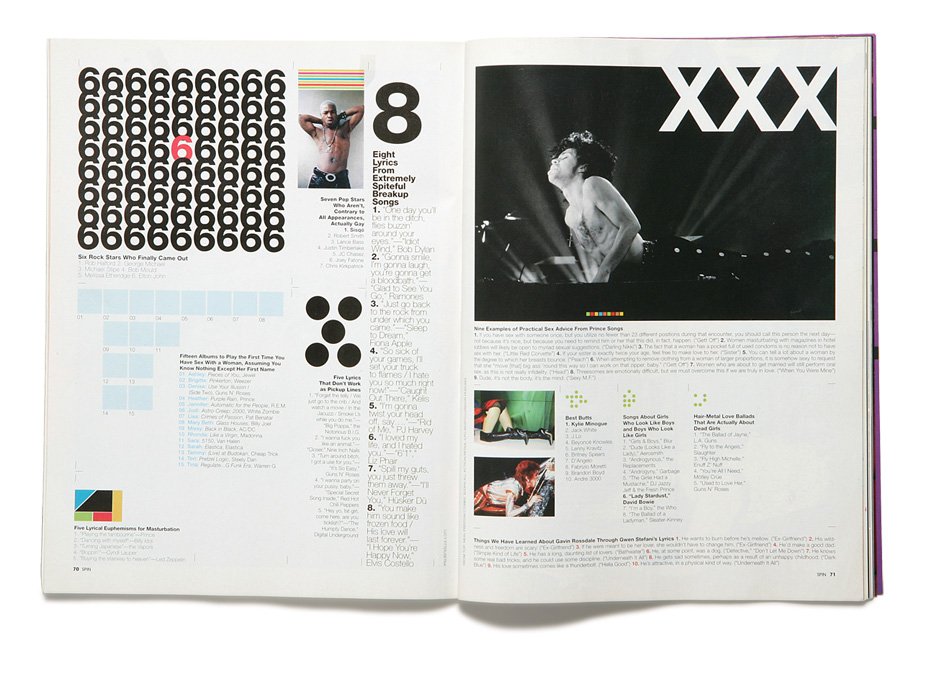

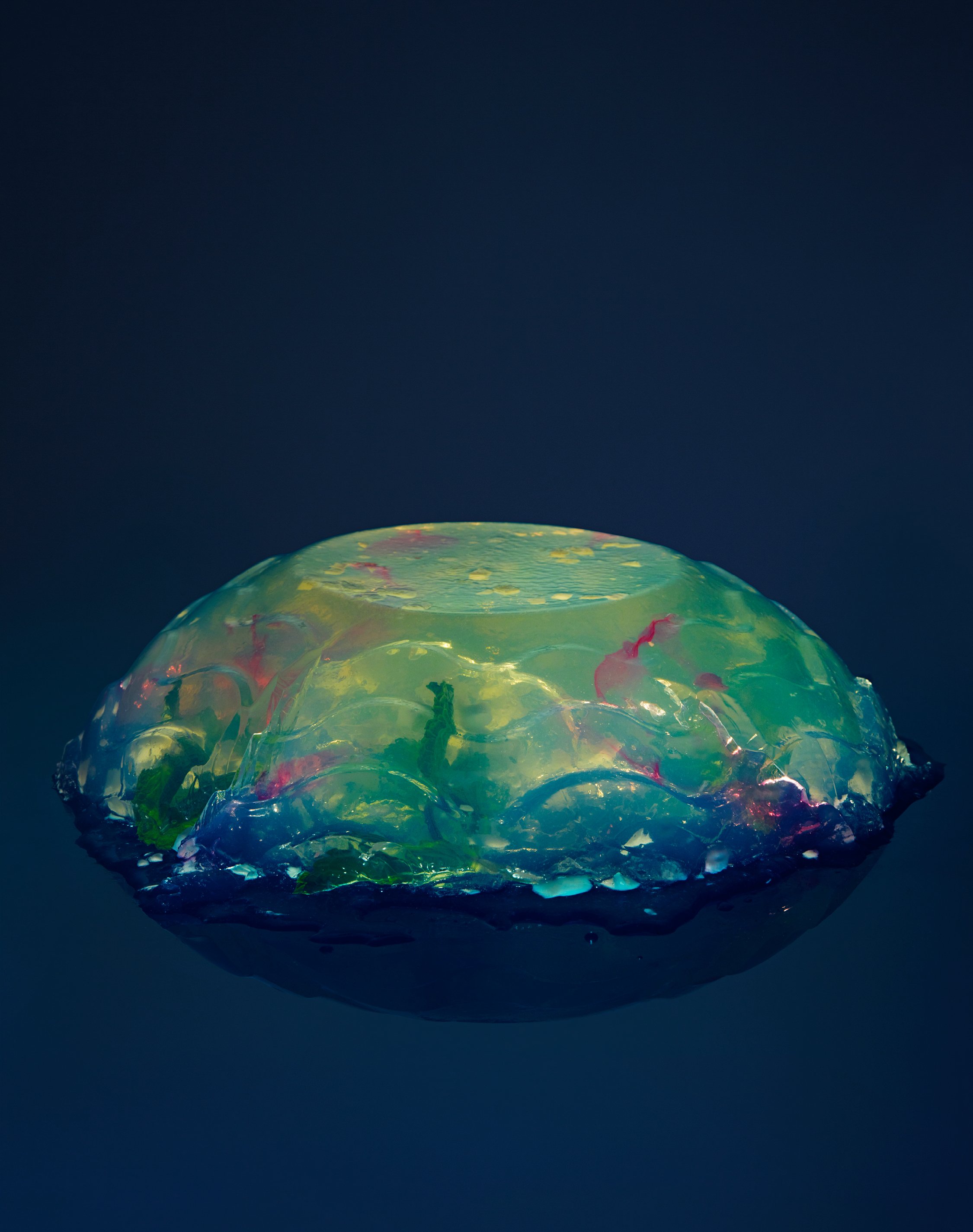

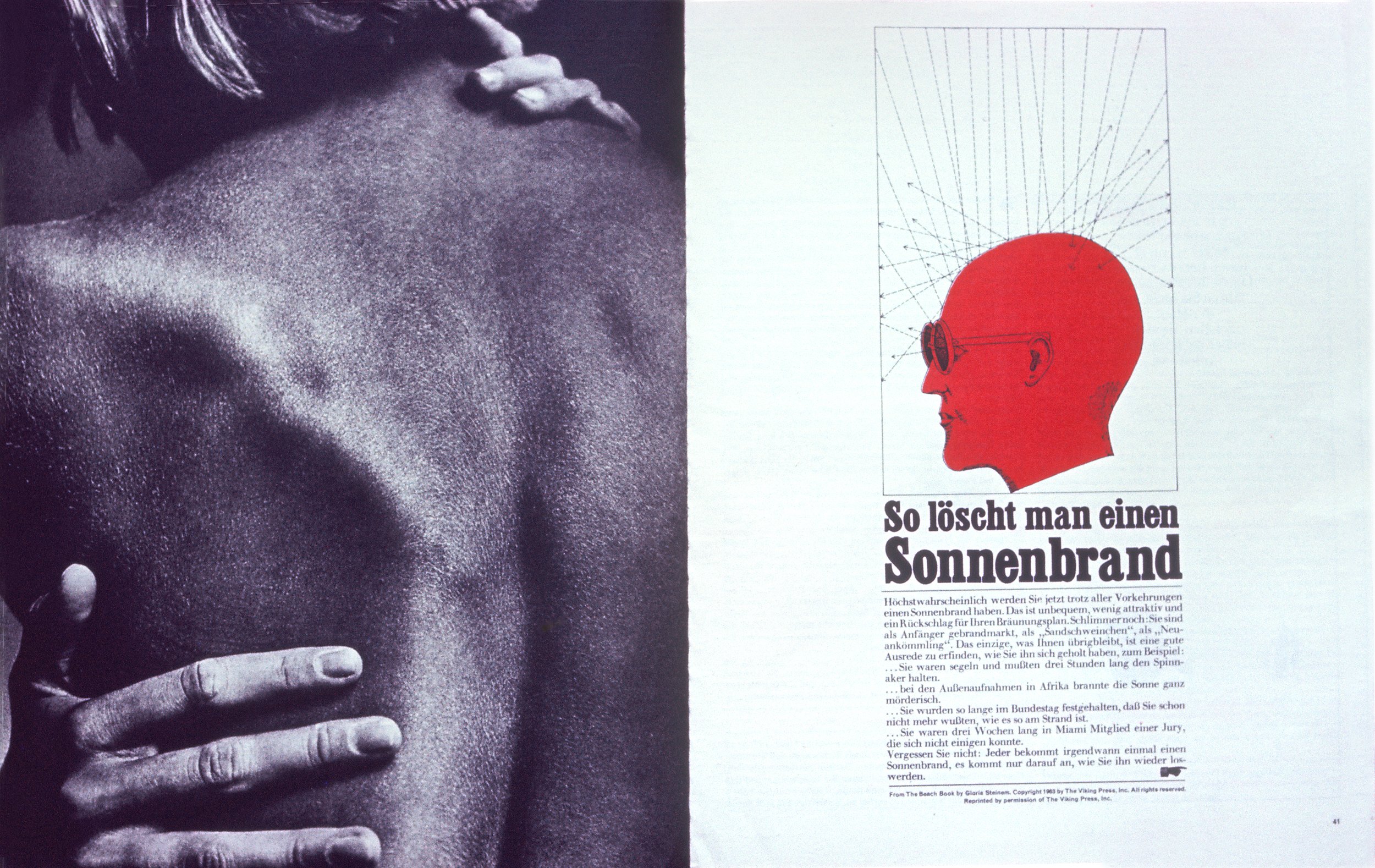

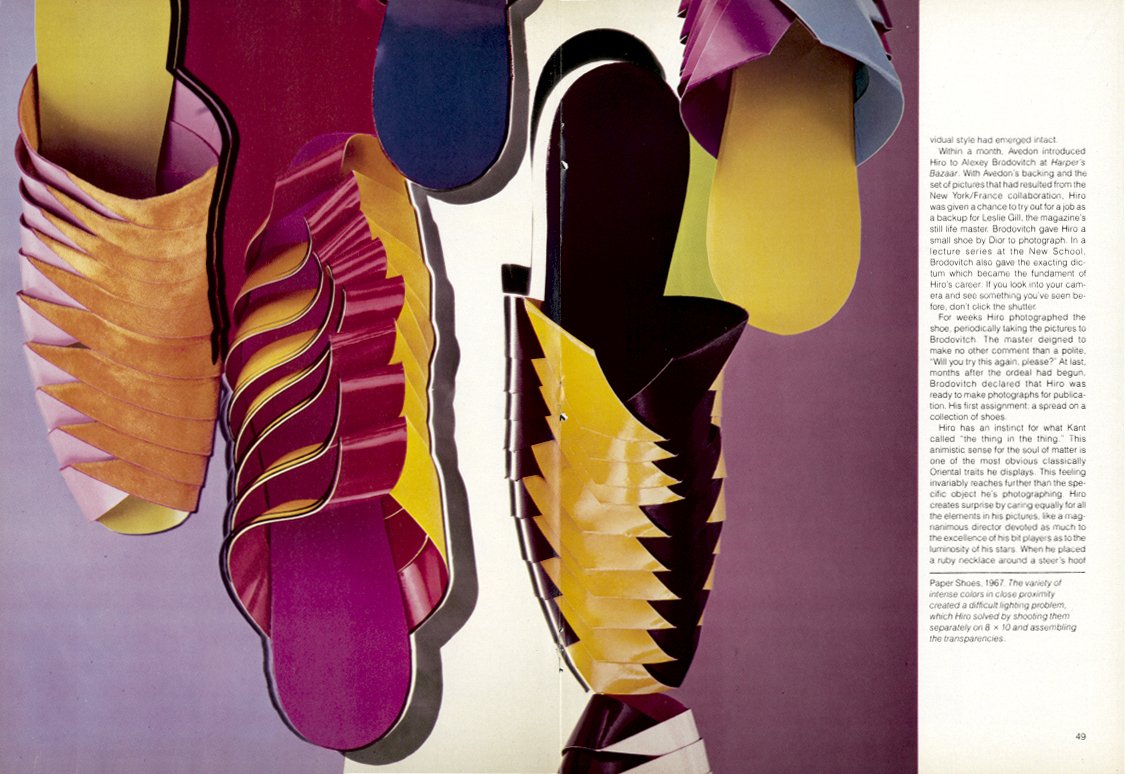

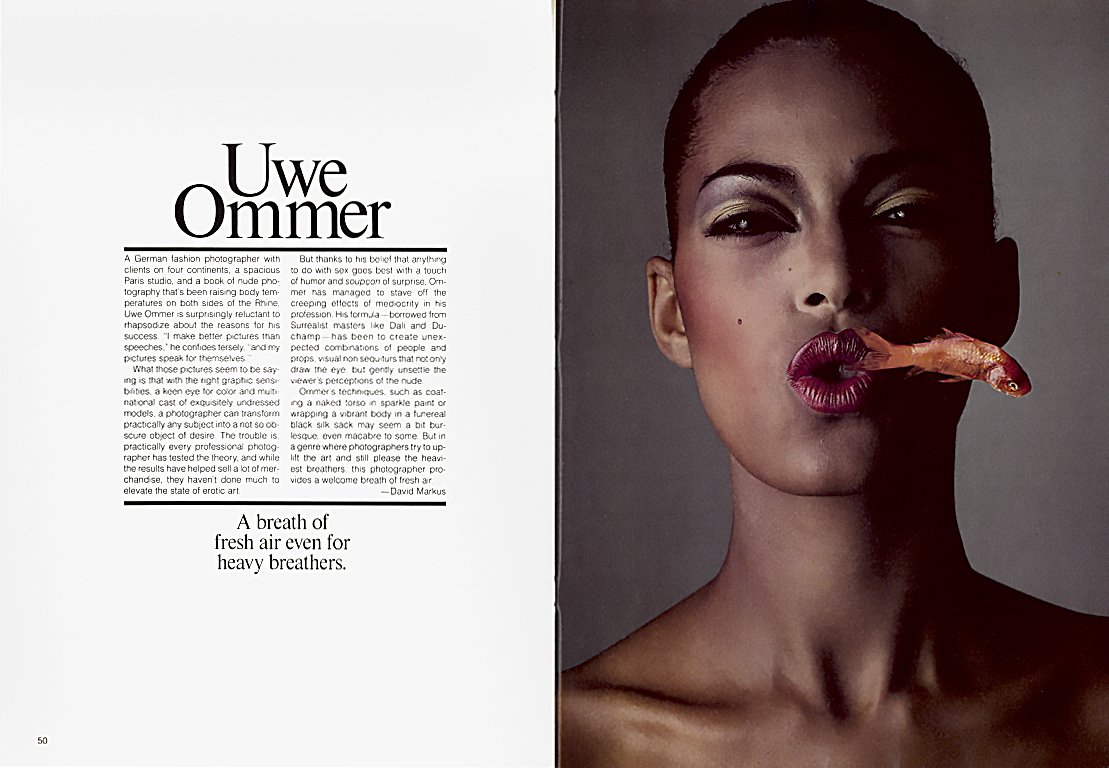

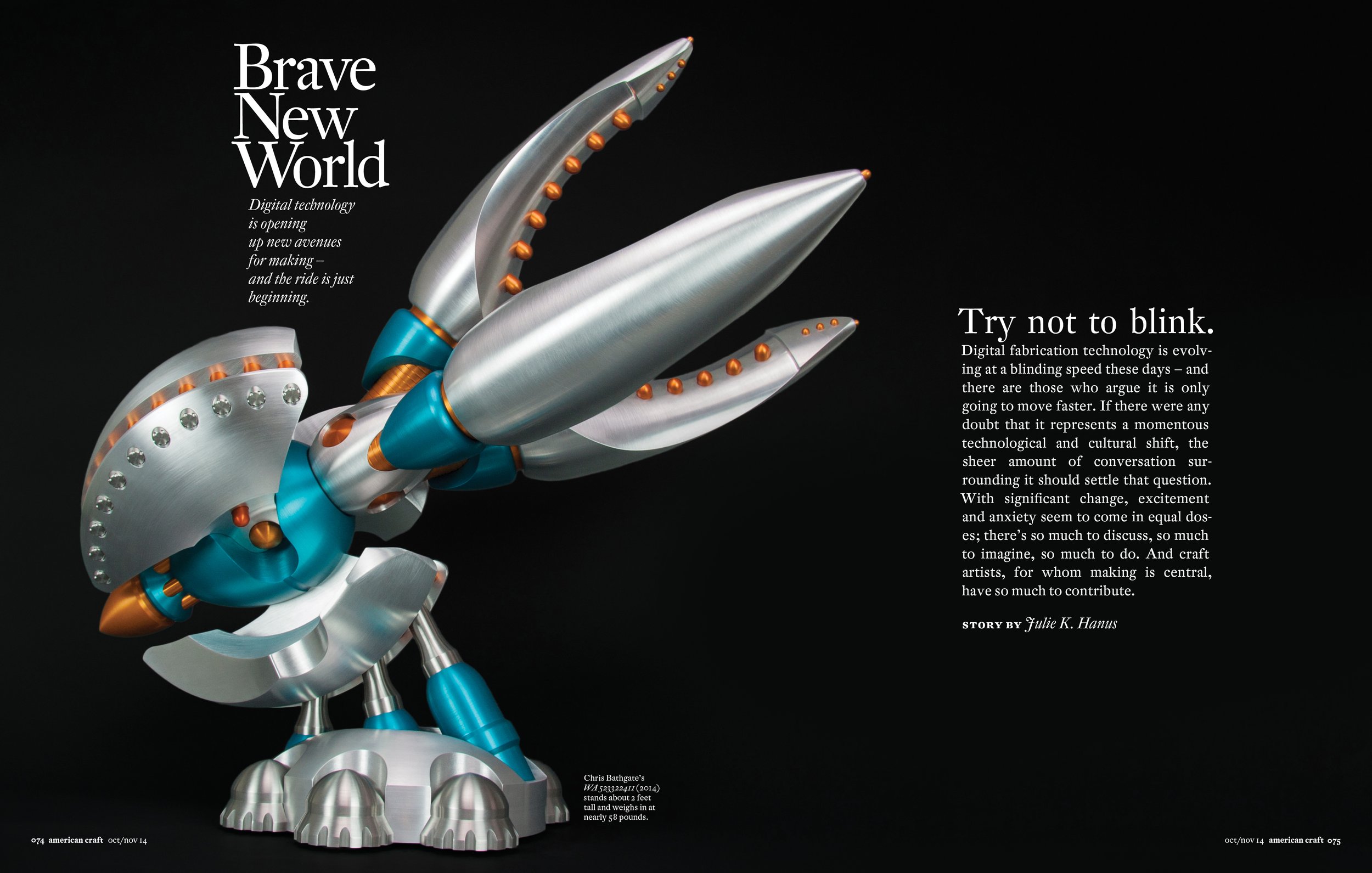

Abstract: The Art of Design, created by Dadich, premiered on Netflix in 2017. Above, trailers for Seasons One and Two.

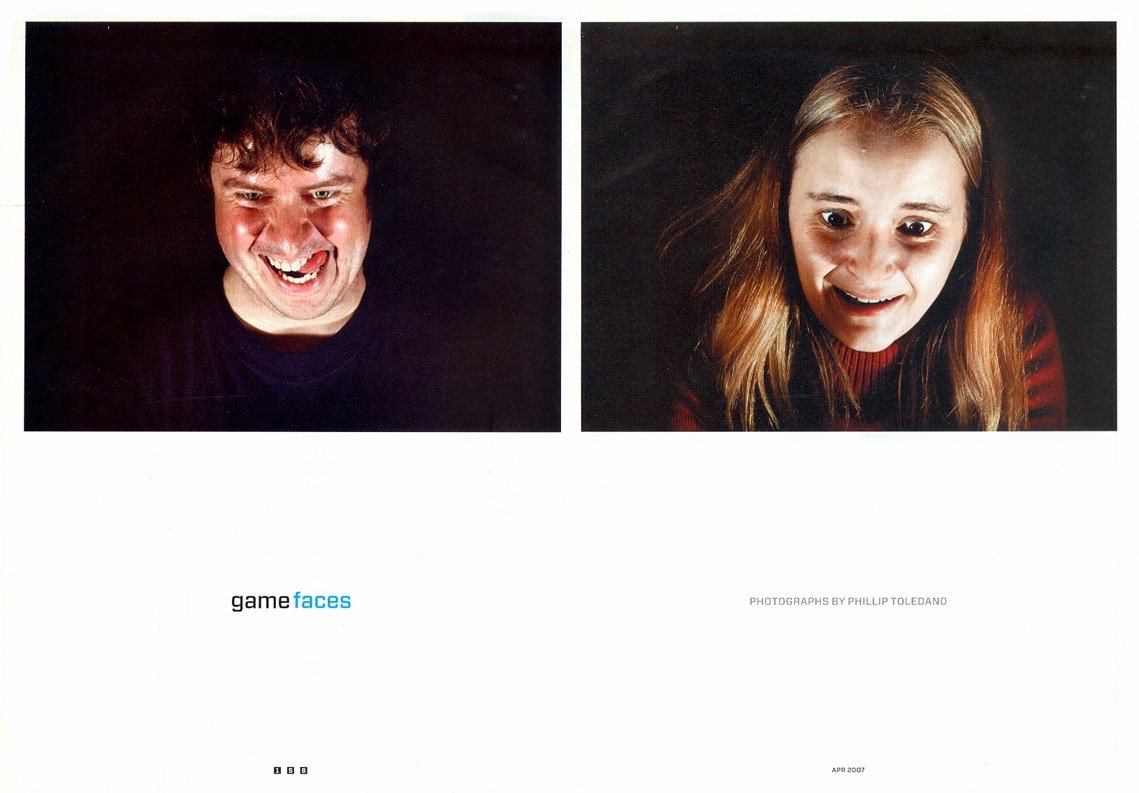

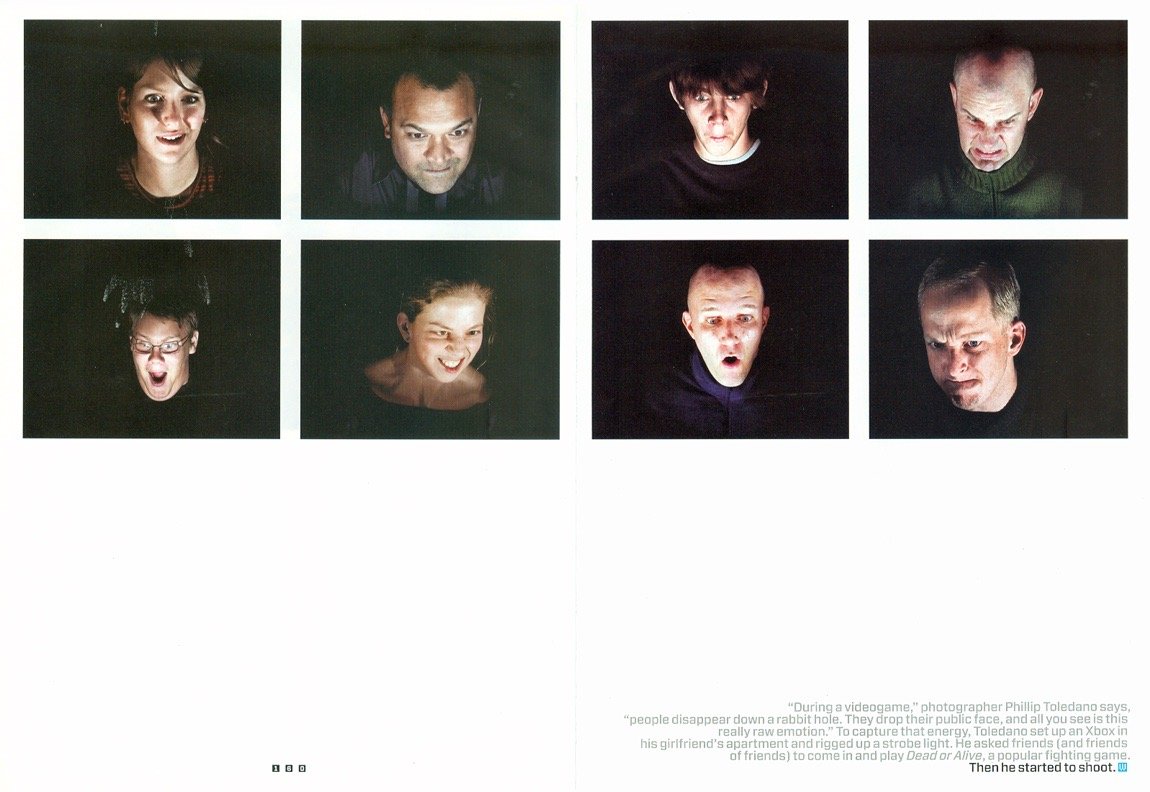

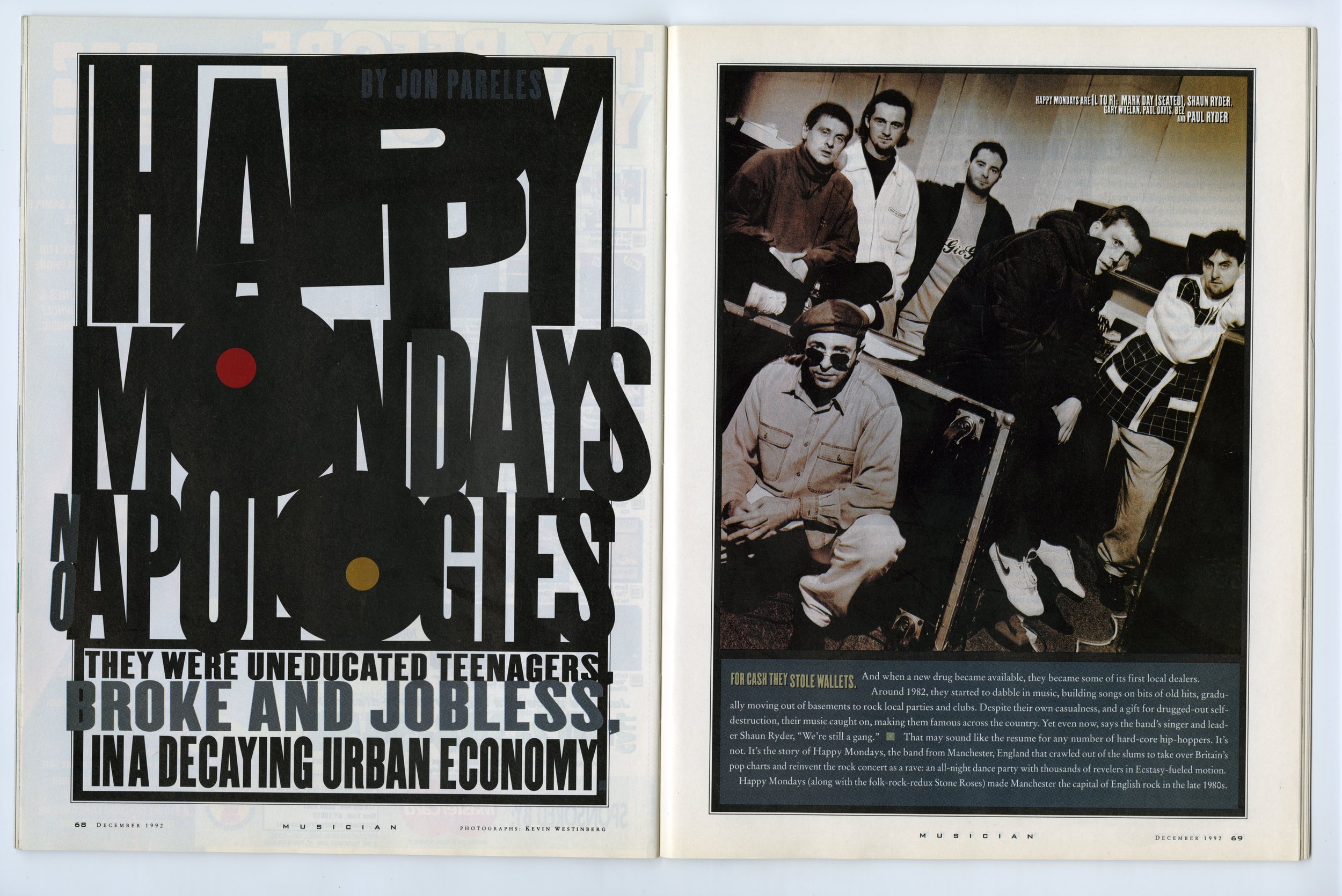

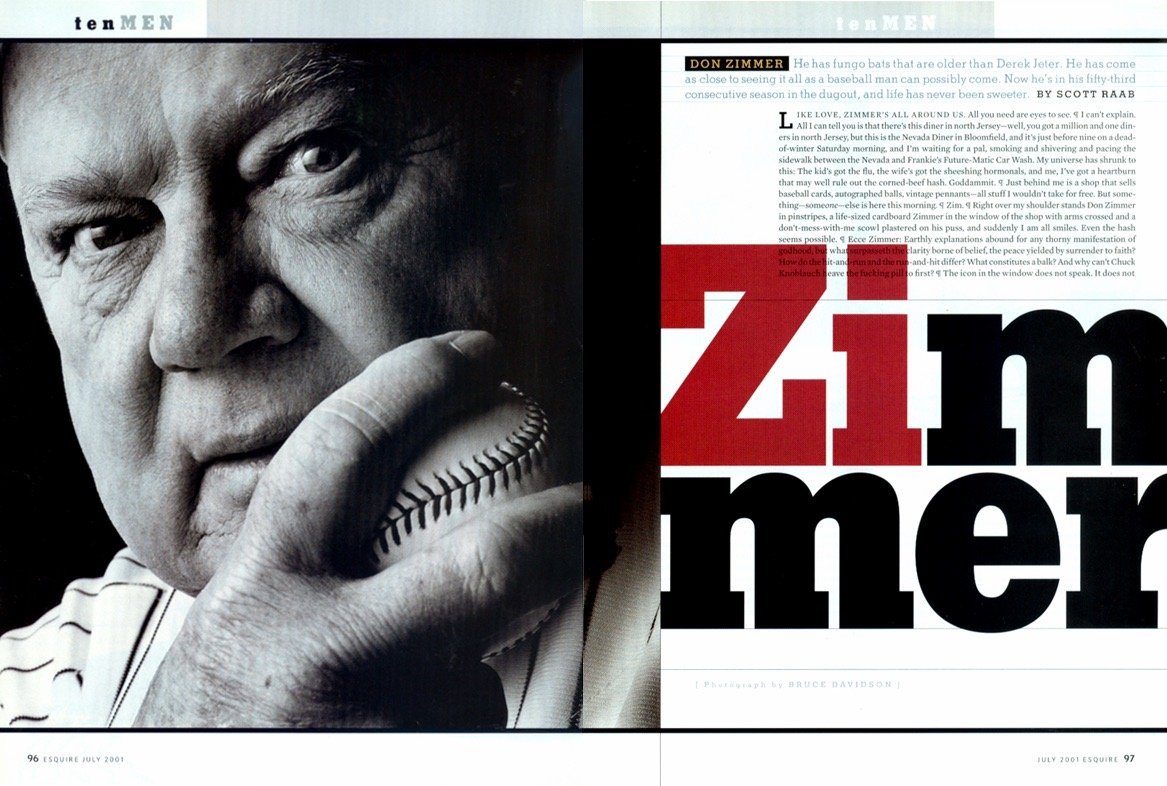

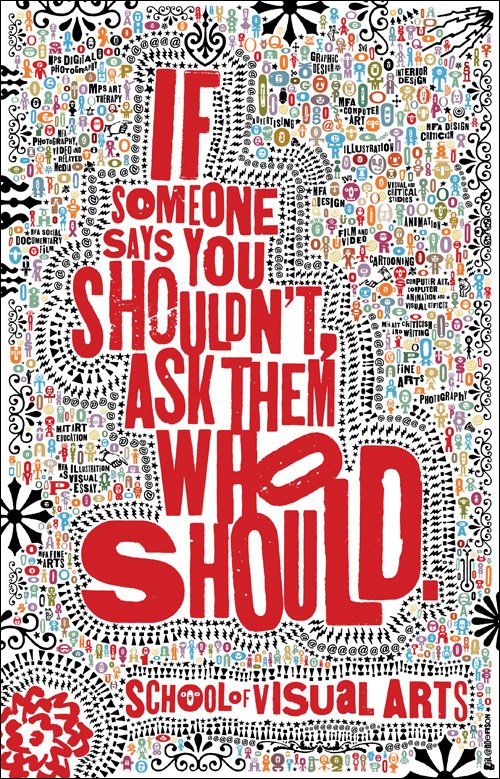

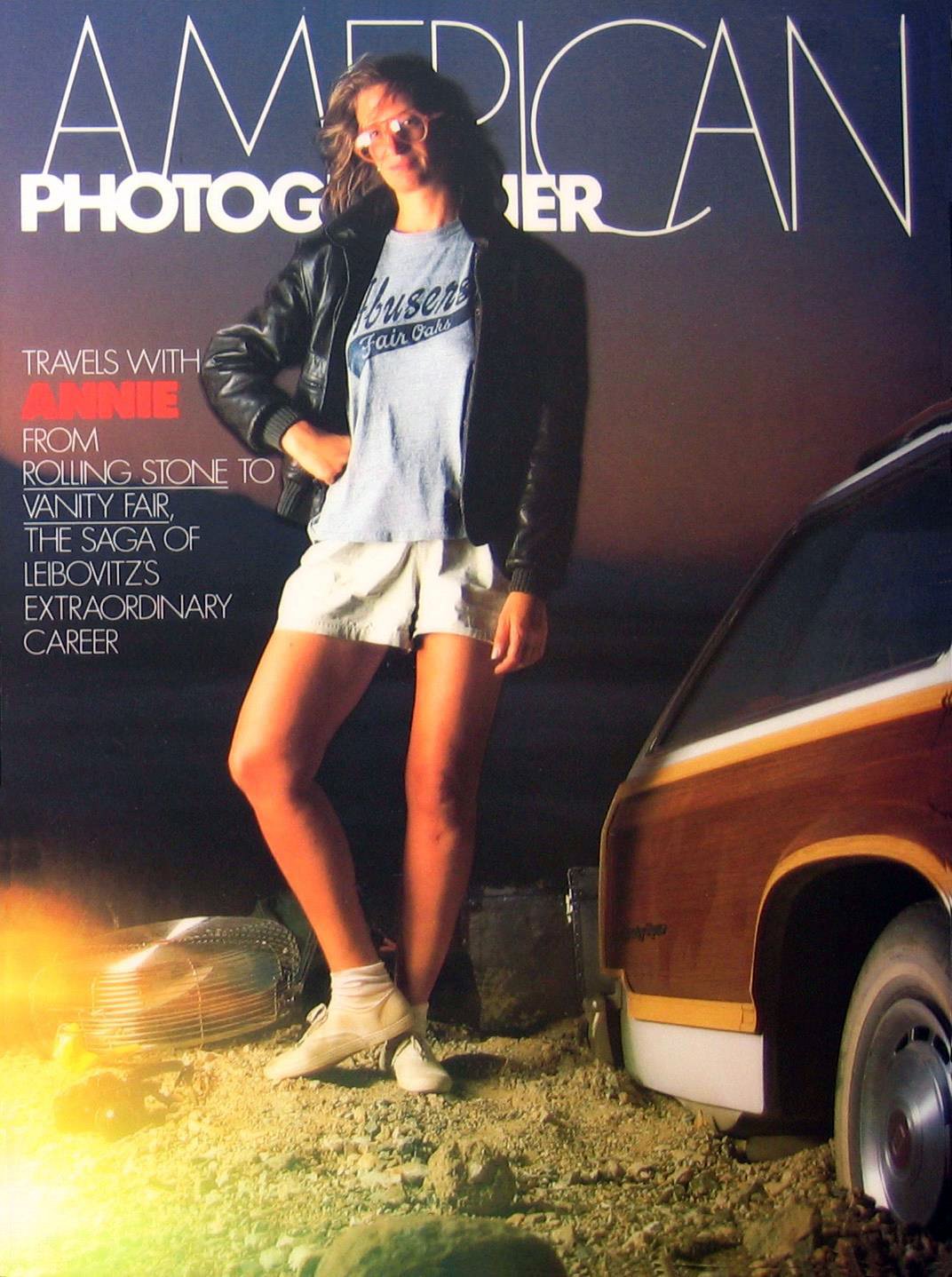

Patrick Mitchell: Speaking of things dear to your heart, we have to talk about Abstract. You created the series, Abstract, in 2017 with Morgan Neville, featuring, of particular interest to our listeners, illustrator Christoph Neimann, Paula Scher, the photographer Platon, and Jonathan Hoefler. Just talk about how and when that idea came to you and a little bit about how you got it made. You were editor of Wired at the time, right?

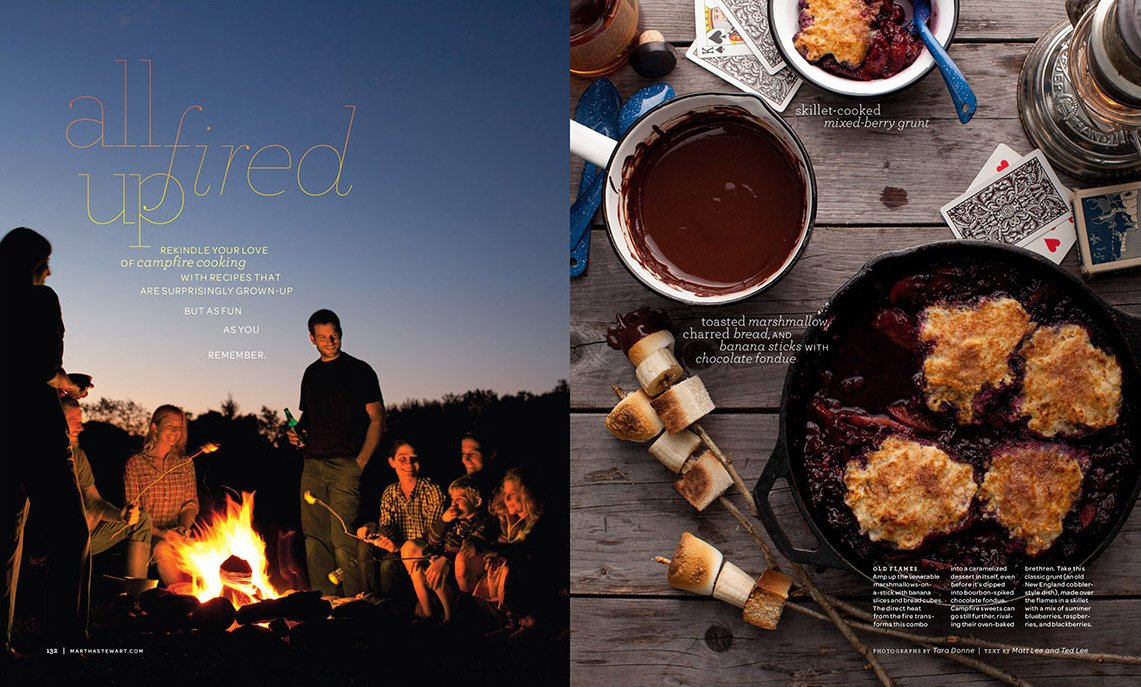

Scott Dadich: I was. So the funny thing is Abstract is born of magazines and many leaders that are listeners here will know—Gael Towey, Luke Heyman, Rem Duplessis, Dirk Barnett, Florian Bachleda—we all got together with the premise that we had all been getting invited to design conferences. And we saw people making businesses out of talking about design and talking about creativity.

So we put it on ourselves to found our own conference. And we put that on in Portland, Maine in 2011. We all co-founded it, and we put our own money into it, and hosted it, and we made a little profit. But it was a blast. And we all stood on stage and we had people we admired stand on stage and talk about creativity and their creative process.

I think we all got pretty busy with day jobs, and I got the Wired editor-in-chief job, and I’d still felt really committed to the idea of Abstract. And so I actually went to all my co-founders and asked to take it and to take Abstract as a name and as an idea, and really push the boundaries of what it could be.

It ended up being something that I just noodled on for a couple of years, but really saw some traction with an idea that we had at Wired called Wired by Design. It was a similar premise that we would bring people together, but beyond the boundaries of magazine-making into broad creativity, culinary, music, architecture.

And we hosted a two-day event at Skywalker Ranch called Wired by Design. And there were a couple of execs in the audience there who gleaned onto it, I think, in the way that I had been thinking about it. One of those guys was a guy named Dave O’Connor. We had been doing a bunch of video work together. He was at Radical Media at the time. And another was a guy named Justin Wilkes.

And together, we just started iterating on it. And Dave said, “If you have thoughts on how to turn what was on stage into a documentary or documentary series, I think we’d have something to bring to Netflix.” And so I built a deck and sketched out what the show could be. And Dave and Justin added their voice to it.

And then we got Morgan on board. And Morgan saw it immediately and understood how to make this show. And we took it to Netflix and we—I remember we were with Ted Sarandos himself, and Ted and Lisa Nishimura green-lit it almost on the spot. And this was the moment when Chef’s Table was taking off, and there was a little bit of corollary to say, this is Chef’s Table but for modern creativity. But Netflix really invested in doc series as a format, and we got off to the races later that year.

Patrick Mitchell: In a weird way, accidentally or on purpose, it’s actually a prototype for GDP, for The New Editorial.

Scott Dadich: You’re right, Patrick. GDP exists in large part because of Abstract. And that two-year period of making Abstract, and getting to be around those design luminaries and see the risks that they took, see the bets that they made, see the process firsthand, it was like getting to be around all those Condé Nast editors-in-chief, but this time at the, sort of, industry scale. And to sit with Paula, and sit with Christoph, and sit with Bjarke Ingels and understand how they were building their businesses felt like an imperative to me.

It was super, super inspiring. And it was part of my thinking that I need to create an entity, an organization that can not only support Abstract, but support my ambition and this team’s ambition around making design a business.

Debra Bishop: Are there plans for more?

Scott Dadich: I wish! We were casting Season Three when the pandemic hit. So I still have that doc, and Morgan and I talk about it all the time. That is one of the most joyful periods of my entire life, getting to make Abstract. And I still hear from people every week who are discovering the series and asking when Season Three is coming.

Patrick Mitchell: I think it needs to come back as a reality show.

Scott Dadich: There we go. Vanderpump Abstract.

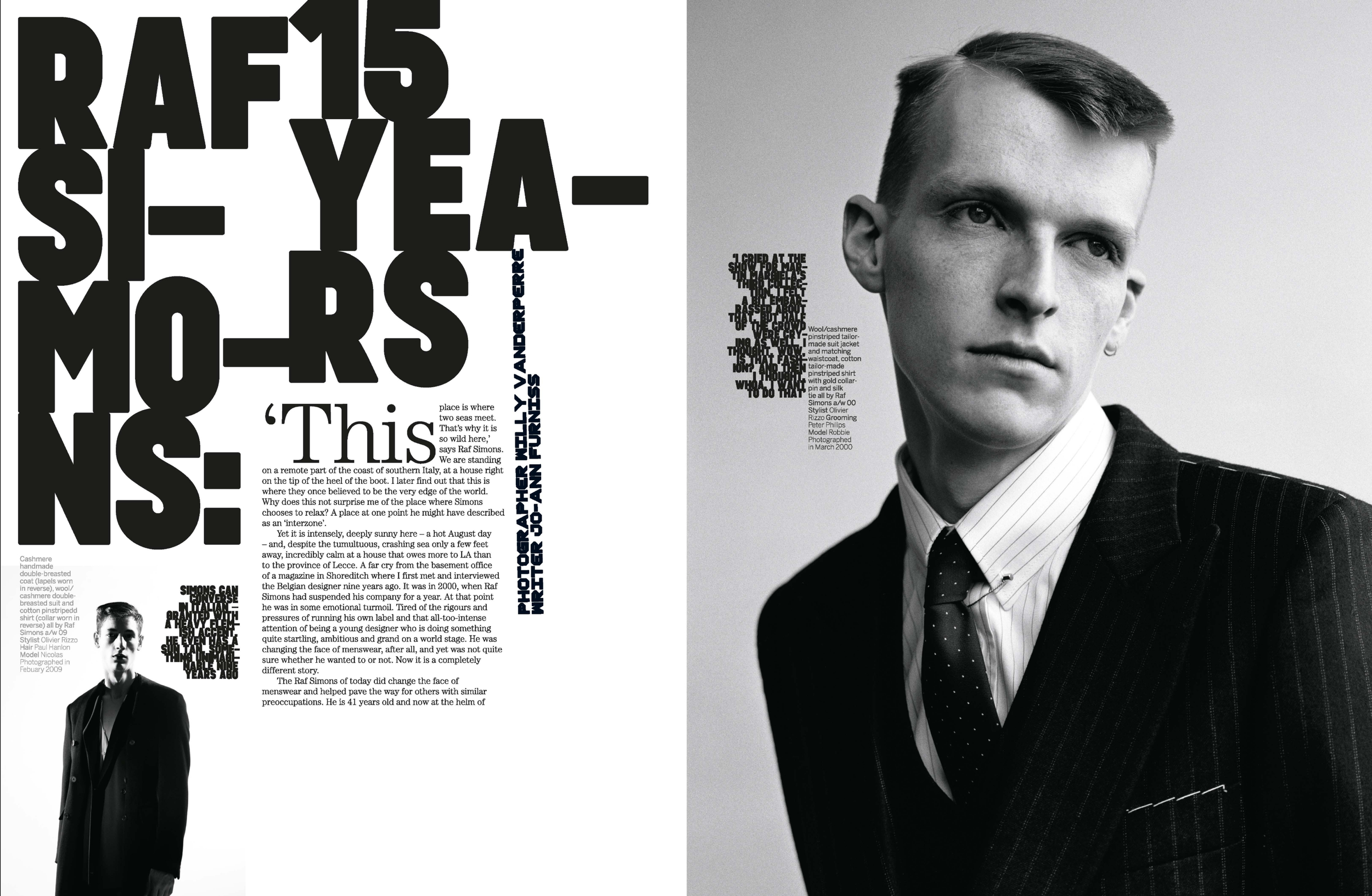

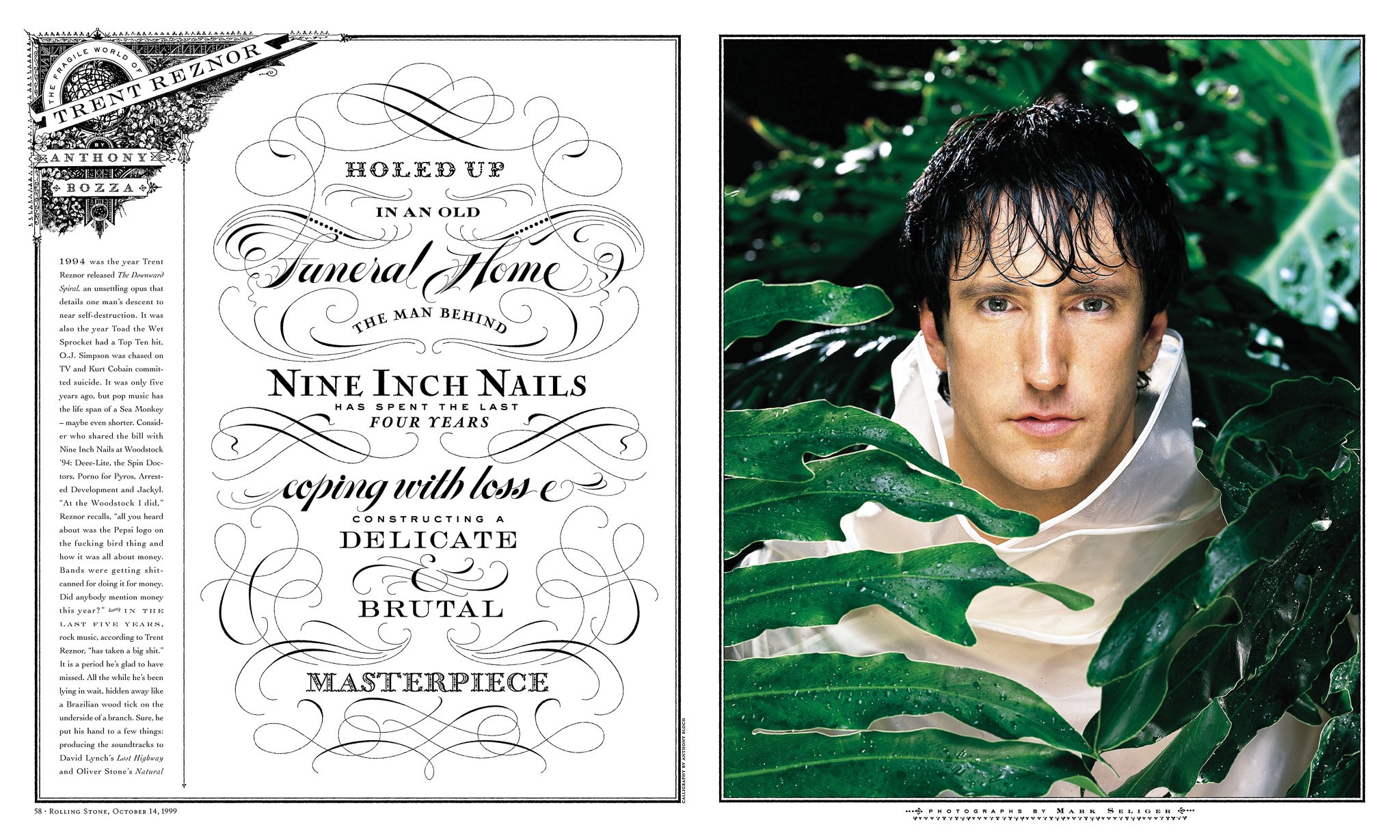

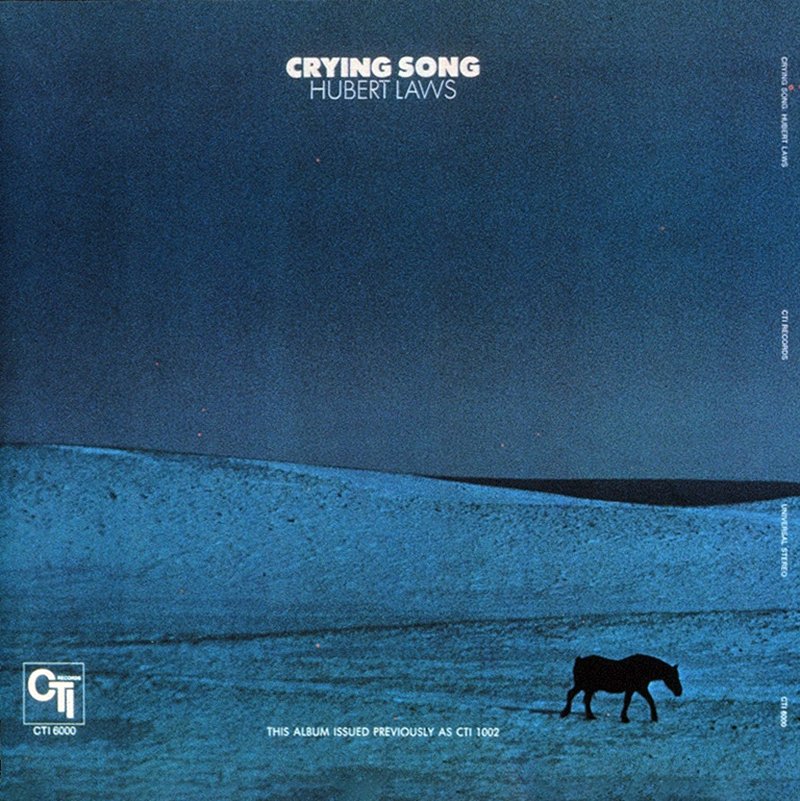

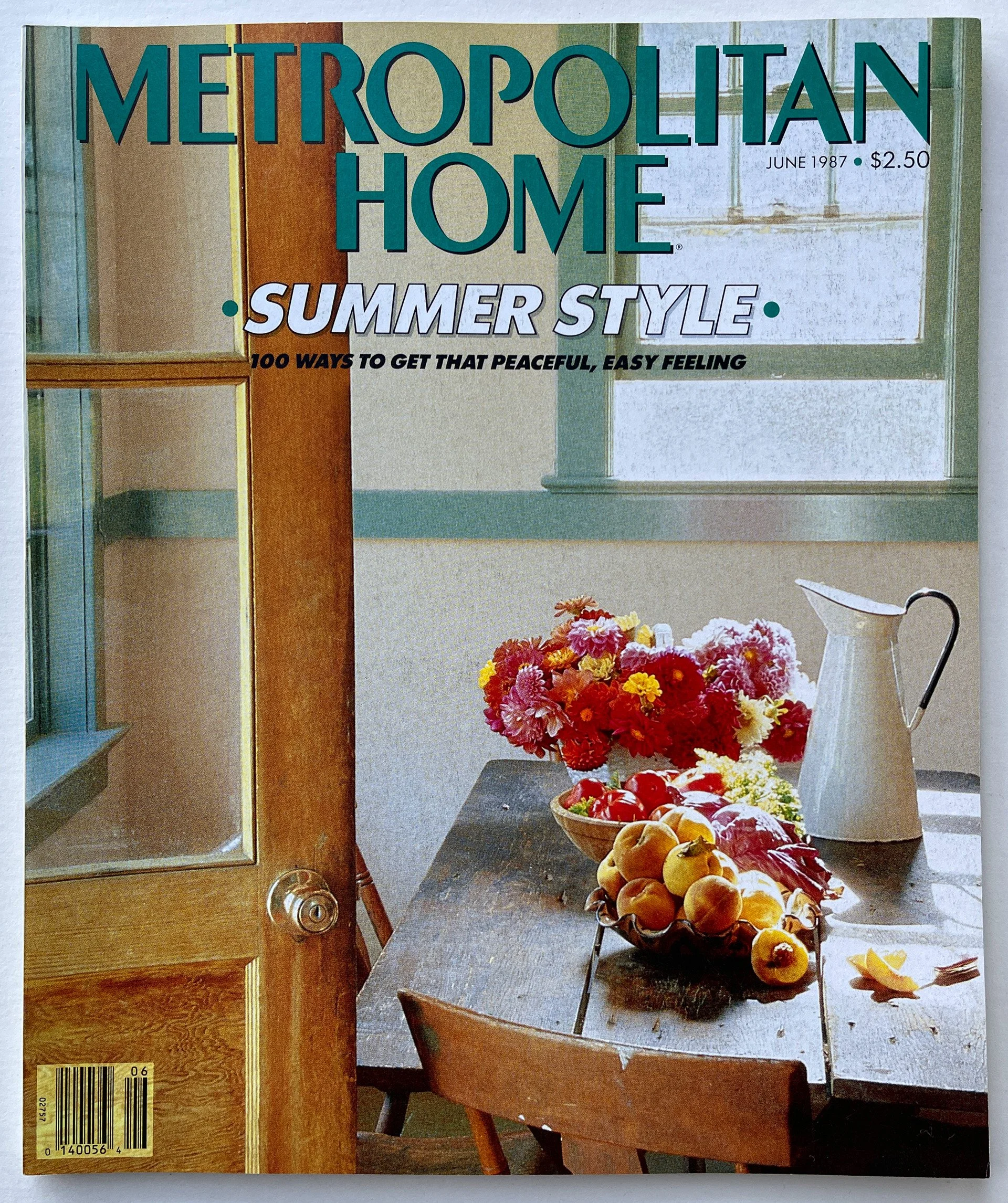

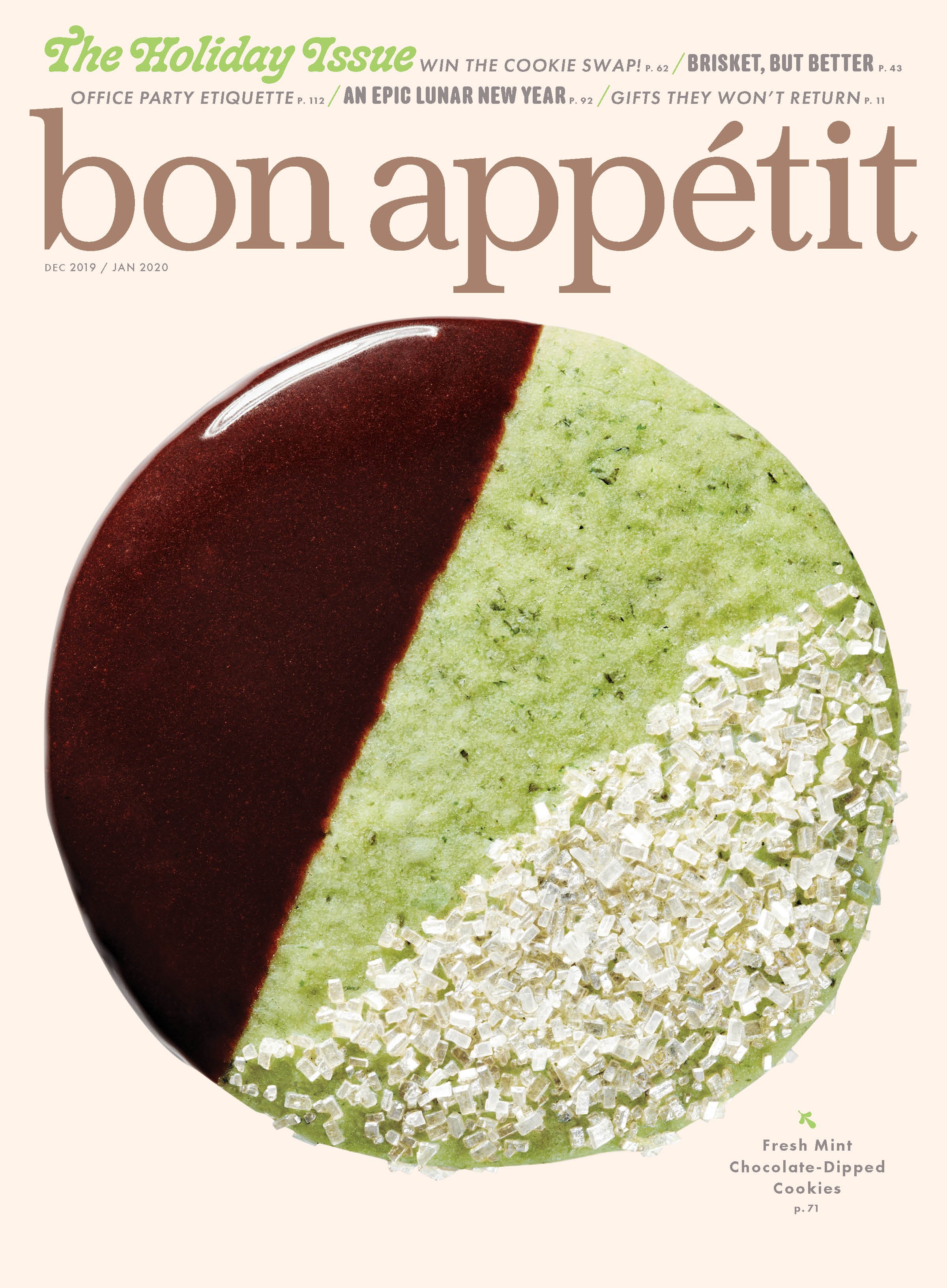

One of many collaborations with photographer Dan Winters

Patrick Mitchell: Speaking of reality shows, we have to talk about The Memo.

Scott Dadich: Oh boy.

Patrick Mitchell: Just so you don’t feel picked on. Deb and I can both share similar experiences. Mine had to do with teaching the younger guys at Fast Company how to coexist with women in the early days of coed bathrooms. Deb’s experience at Martha Stewart, I’m sure was...

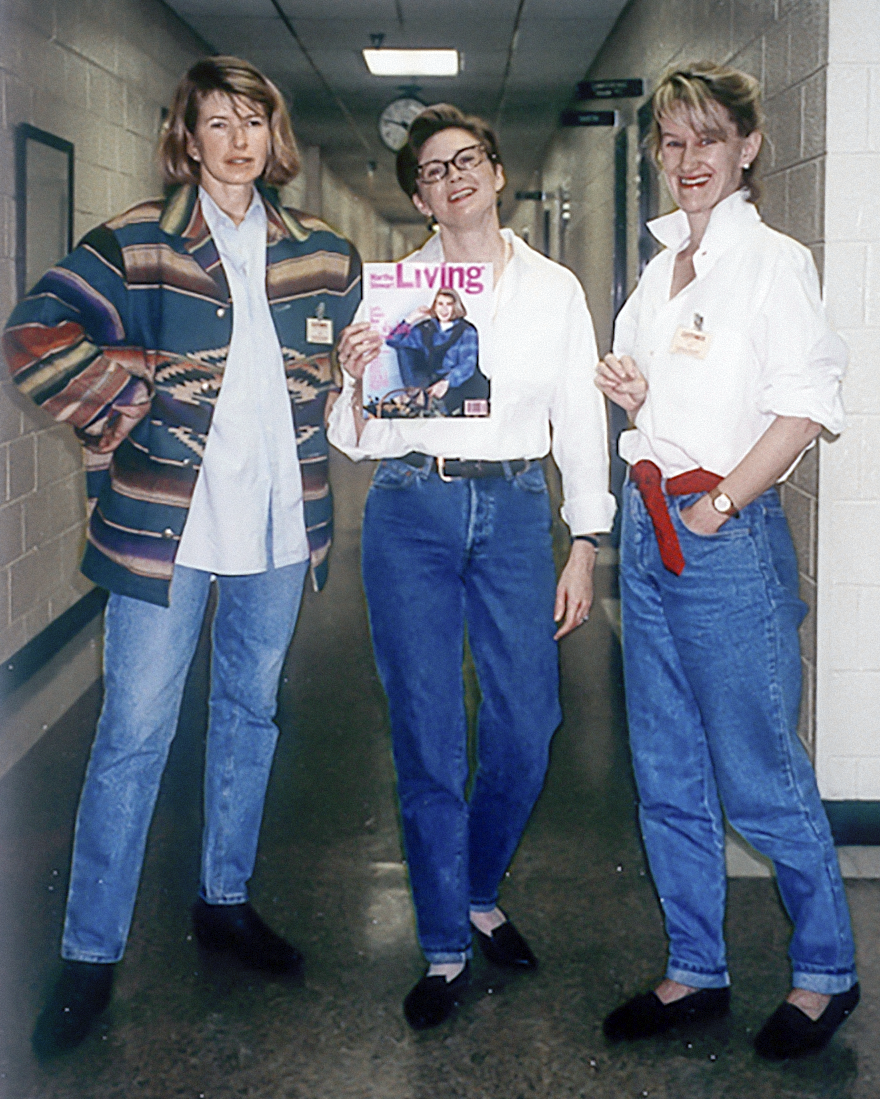

Debra Bishop: …Oh, no, we had cleaning staff around the clock at Martha Stewart. You were expected to keep—remember it was an open plan, Scott, you’ve been to Martha Stewart many times.

Scott Dadich: I have. I might have Martha to blame for this memo.

Debra Bishop: Yes, that’s what I thought.

Patrick Mitchell: So for those who don’t know, this was...

Debra Bishop: Only I would know that.

Scott Dadich: Yes, you would know that. You would know that and Gael would know that, but…

Patrick Mitchell: ...Wired had moved into brand new offices. Spectacular, stunning...

Scott Dadich: We didn’t move. We redesigned. We tore the whole thing apart and rebuilt it from scratch.

Patrick Mitchell: And frankly, The Memo is like every designer’s wet dream—to place the highest priority on aesthetics. But so the memo said, quote, “The offices are an embarrassment. Coffee stains on the walls, and countertops, and desks. Overflowing compost bins. Abandoned drafts of stories and layouts full of highly-confidential content. Day-old, half-eaten food. And yes, I’m going to say it, action figures.” In the group of three that’s here right now, it doesn’t seem irrational, but it sure got picked up a lot.

Debra Bishop: Seems fairly normal. Action figures? For sure.

Scott Dadich: Sure, why not? Absolutely.

Patrick Mitchell: That’s how magazines are made. But a lot of people had a lot of fun with that. Your thoughts?

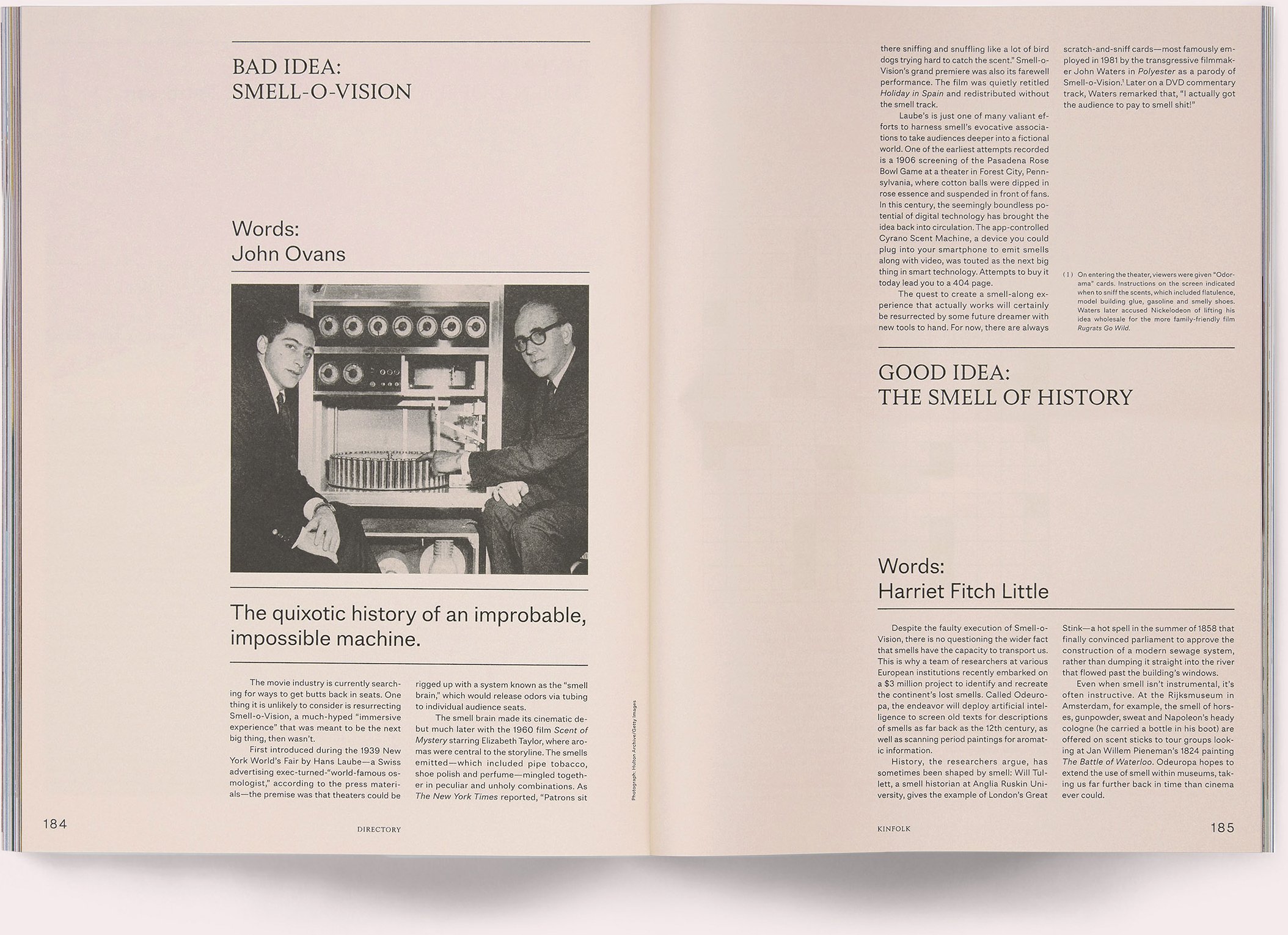

Scott Dadich: Oh, God. What an ill-advised—what an ill-advised communication. I really struggle. I was listening to Korpics’ episode and I really identified with what he was describing in the OCD tendencies. I find myself to be a bit of a perfectionist, and it does, like, it lives deep inside of me and I’ve done a lot of therapy and a lot of coaching work to move past that. Yes.

Debra Bishop: Okay, so then I can ask the question: When you get up in the morning, are you the same Scott that goes to work in hyperdrive—it’s constant?

Scott Dadich: I have an amazing coach. I’ve been with a couple of different coaches over the last decade that I just credit hugely. I think there are a couple of different Scotts. And there was Wired Scott, who wrote that memo, and I don’t think he’s around much anymore. Hopefully for the better. But I’d also say Martha definitely was an influence on that. And I had a conversation with her about that…

Debra Bishop: …that Scott has been rehabilitated.

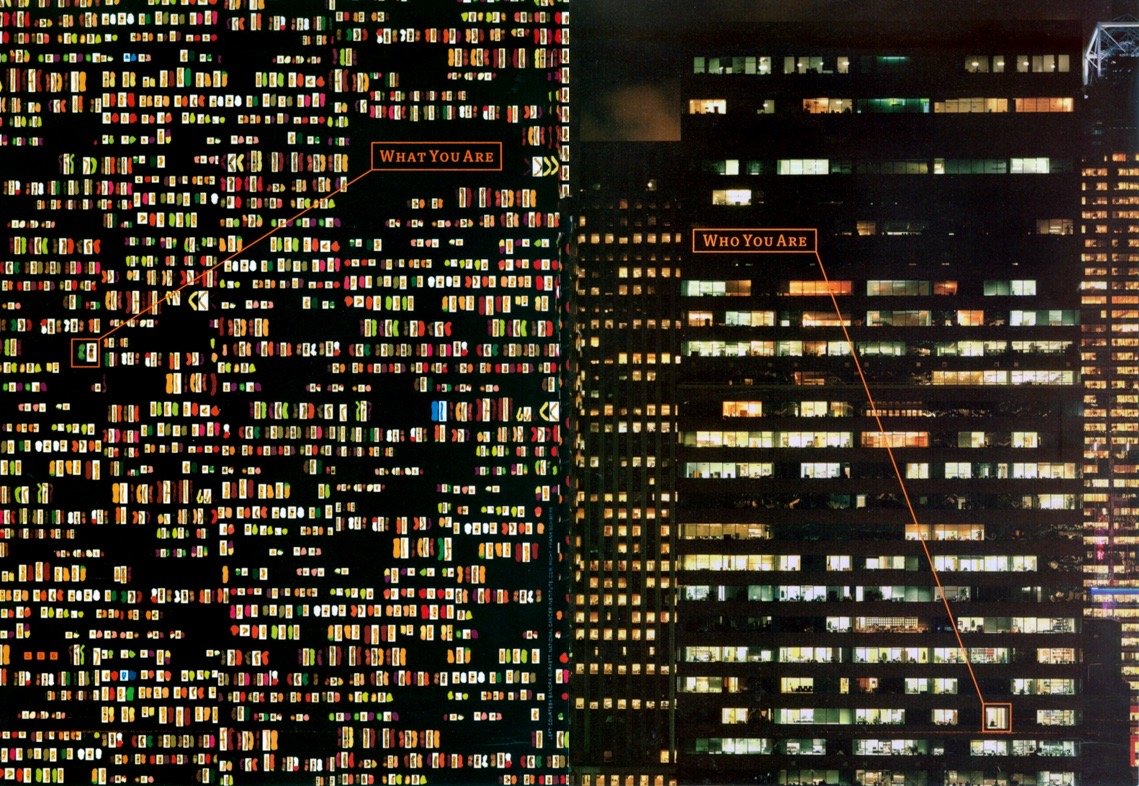

Scott Dadich: Yes. But there was also like, there was a character that you needed to play as a Condé Nast editor-in-chief that was almost like an avatar of yourself, that was mostly designed by the business side, and mostly propagated by the publishers. But sometimes you got a little ahead of yourself when it came to who you actually were. And what you were doing is playing that role.

Debra Bishop: Maybe you could talk a little bit about what exactly Condé Nast Digital was and what you were planning to do with it. But for the most part you were in charge of creating digital editions for each magazine, correct?

Scott Dadich: So Condé Nast Digital was its own entity. Actually separate from the, sort of, print magazine world. And it was probably symptomatic of that original Wired.com/Wired magazine conversation that not all editors-in-chief had permission, or budget, or authority to run their digital newsroom.

And that was one of the conditions that Chris and I wanted to set up—that the digital edition, the digital version of the magazine would be of-and-by the same people that made the print magazine. Not because we thought we were better, but because there was a condition set around the editorial coverage and the editorial charter and mission of that coverage to take big swings.

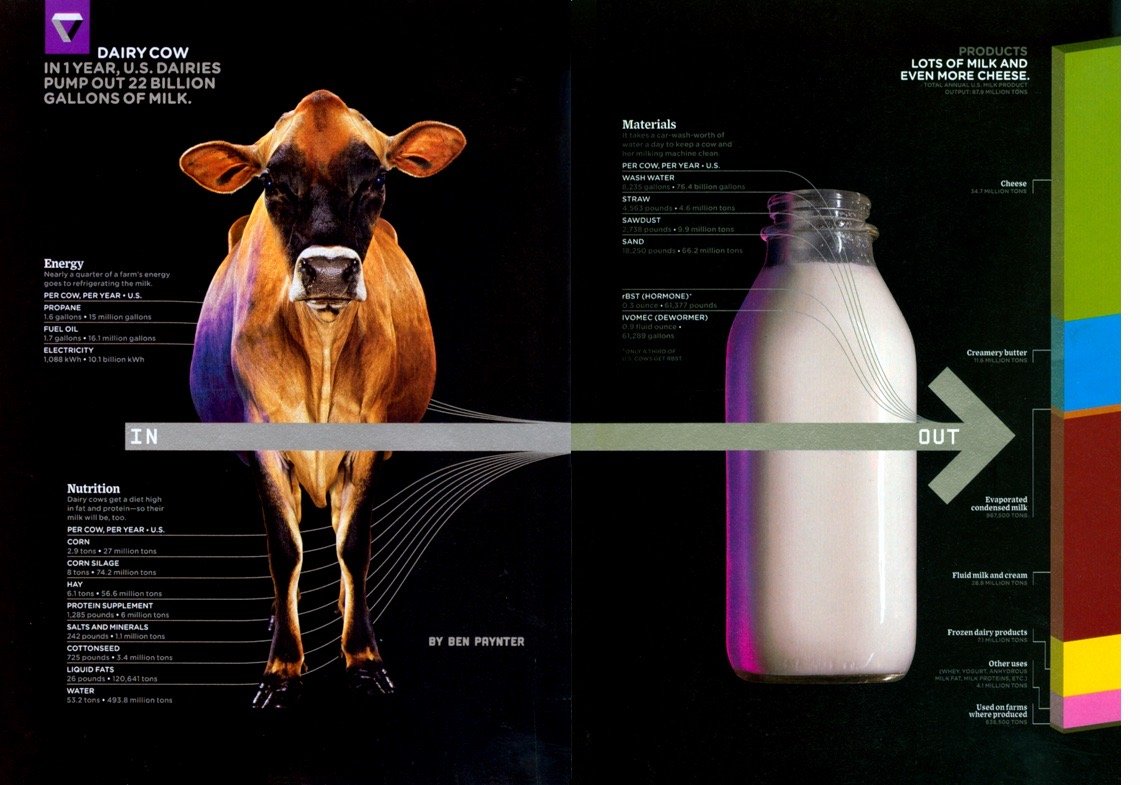

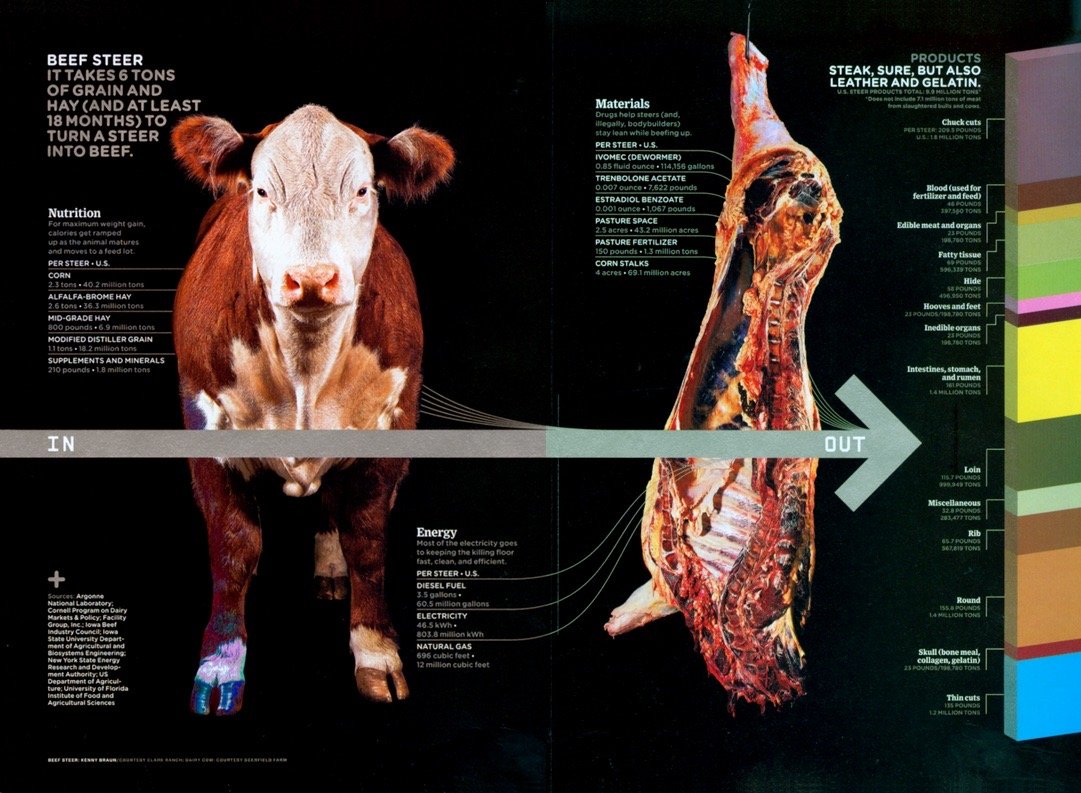

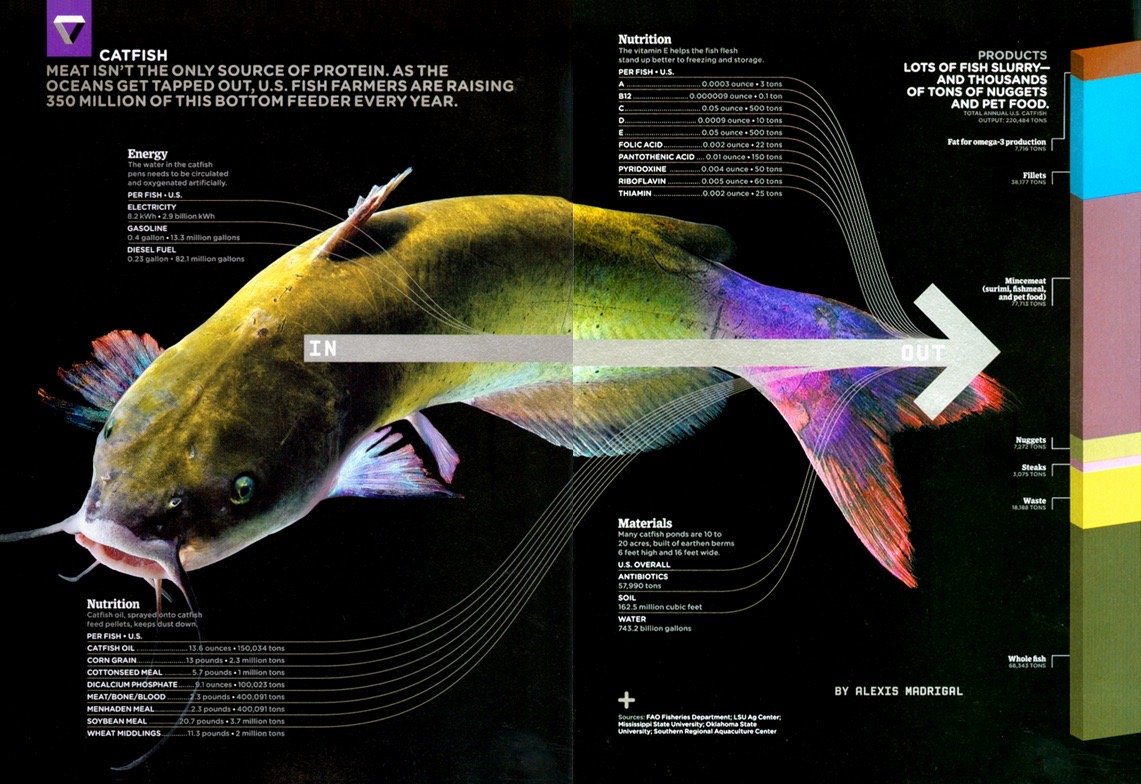

We also had a better budget. We had a print budget to send people on big photoshoots, and commission big infographics, and illustrations, and pay $5/word for great writing and reporting. So we wanted to make sure that was the very soul of what we were trying to do. And, we built the Wired digital edition with our friends at Adobe, and in full partnership with Apple and their support and coaching.

I had a meeting with some leaders at Apple, who are still there, in August of 2009, where we had this sort of vision demo and I had built a little reel of thinking, Here’s what it could look like. But it was following the success of that, that Tom Wallace, again, as editorial director of Condé Nast asked me to New York and asked me to think about what The New Yorker could do with these tools and these technologies.

And we had a great conversation with David Remnick. And David and Pam McCarthy raised their hand really to be next and thinking about, not only how The New Yorker could deliver into this device and into this frequency, but how it actually had the opportunity to change the business model of the publication and how it might enable that idea of a membership to The New Yorker.

And having the Kindle come out, and having all the other activities that were happening, and different kinds of tablets really helped propagate the idea that you could create a higher value for the relationship with the title and you could access it in a bunch of different ways.

“Part of my thinking was that I needed to create an entity, an organization that can support my ambition and this team’s ambition around making design a business.”

Debra Bishop: So what caused the ultimate demise of the app development?

Scott Dadich: I think we were wrong-headed in a couple of different areas. We made mistakes based on the technologies that we had. We made mistakes based on where the economic conditions forced us, whether that was a rate-base model or trying to protect print advertising pages, down to probably what was an erroneous assumption that people wanted to read magazines on tablets. Even today, I don’t want to read a magazine on my tablet. I read it a lot of different ways, but much more on my phone probably than anything else.

So I think there are a number of factors that caused its ultimate failure. But I’m also really proud of the work. Mostly because it changed the nature of an editorial conversation and a storytelling conversation out of column inches and number of pages into the true ambitions of what the narrative and what the journalism required.

Whether that was an audio format, or a video format, or experiential format, it broke us out of a cycle and a posture that dictated the outcome based on format. And I think that ultimately is something I’m enormously proud of. And I think we’re seeing the right titles and the right leaders make great progress with that idea.

Patrick Mitchell: This is a big bugaboo for me because, you know, the iPad came out in 2010, but the internet, et cetera, came out 12-15 years earlier. And it just seems like the five families—Hearst, Condé, Time, Meredith, Rodale—they just seemed like they twiddled their thumbs waiting, not knowing what was coming. And then they decided the iPad was it. And, Now we’re going to take digital seriously. And you’re right—it’s the way you describe it. It ended up not working because that’s just not how people wanted to do it. And they just, they keep their head down buried, still with the same recipe: subscribers, advertisers, cut costs, cut people. I successfully avoided having to deal with an iPad version of anything, but I’ve heard horror stories. Our friend Gretchen told me when she was the art director at House Beautiful, which must’ve been around this time, and at that time they were trying to do an iPad edition, which meant you had to not only produce your magazine, but then you had to do a vertical version for the iPad and a horizontal version for the iPad. And then, Whoa! Wait a minute! Let’s have those same people who are now doing triple the work—let’s throw Veranda magazine at them. Let’s create a house design group, and combine a bunch of magazines, and have that same group of people now produce ALL of this for ALL of these magazines. And, boy, it just seems so wrong-headed.

Scott Dadich: It was really tough. And I am super-guilty here in thinking that was going to be a requirement that we had to have all those conditions and we had to have all those postures. Part of that, Apple was a very strong advocate that you let people use things in the way they want to use them. And one of those conditions was, If they want to look at a landscape, it ought to work in landscape. They want to look at it vertically, it ought to work vertically.

But it was also too much. Looking back, it was just too much to ask. And I think we understood that it would be hard initially, but we were also under the impression that the tools and the technologies were going to out-pace that need and that it would get a lot easier, a lot quicker than it actually did.

Patrick Mitchell: And yet still no real innovation from big publishing to this day. All right, I have to ask you, this is personal, but I’m in the middle of reading the Condé Nast “canon.” I just read Tina’s book. I’ve read Anna’s book. And now I found this old Si Newhouse book. I don’t know, it’s seven or eight years old. Have you read this book?

Scott Dadich: No, I need that. You need to send me that, Patrick.

Patrick Mitchell: It’s funny because I’m reading it on my iPad. I’m reading it on an iPad!

Scott Dadich: Imagine that!

Patrick Mitchell: But, my God, what a company. And I had no idea that Si bought Tina her house. That Graydon’s vacation house came thanks to an interest-free loan from Si. We interviewed Linda Wells yesterday from Allure and she talked about her interest-free loan on her house and a free car that she got. Si just loved to give out money. And I’m wondering—yes, I do know about that sweet apartment you had when you were in New York. In the Gehry building, right? Maybe you don’t have to say anything. You can just nod your head.

Debra Bishop: He’s nodding his head.

Patrick Mitchell: How much interaction did you have with Si? And what was your take on Si and Condé, just from a kid from Lubbock’s perspective?

Scott Dadich: I loved working for Si. I absolutely adored that guy. He was described to me in the early days, when I was working for Chris Anderson, I knew that Chris had to go every month to do the print order, and bring the printed magazine and show it to Si, and sit down and flip through it. And it was pretty soon after hearing about that, that I found myself in the same room with Chris every month. So the chance to get to go to New York every month and have that meeting with Si and understand the questions that he was asking and the prompts that he was pushing us on made the magazine better. Unequivocally better.

It was hard because you put yourself into every single page, and every single decision, and every single story in the issue. But then to have Si say, just bluntly, “I don’t get it. This doesn’t make good sense for this time, or this cover, or this magazine, or that photo.” And obviously the work that he had done with Alex Liberman and a host of incredible editors and collaborators. Si was just amazing.

And so I felt really fortunate to be in his company, and in his care, and in that room. When it came time for me to take over Wired, I had to interview with Si, and I had to describe what I wanted to do with Wired. And he loved Wired. He had loved it since the very first issue. He was an investor in the enterprise that became Wired.

There was a great personal attachment that he held for it, and I just considered it an absolute privilege. And he was getting up there in years even when I started working for him, and then even in later years, when he was less well, I took enormous care to appreciate the rarity of those interactions.

And I think I was probably one of the last editors-in-chief that Si actually named. I think it was me or Adam Rapoport. But it was not long after that, that he stepped out of the day-to-day.

Patrick Mitchell: The book talks about the limo that picked him up every day at four. But he did take a nap after lunch. And he went to the gym. And then he took another nap after the gym before dinner. So that’s how he pulled that off.

Scott Dadich: Yeah, you’d catch him in the afternoon in his sweats. So you knew if he got the work out in or not.

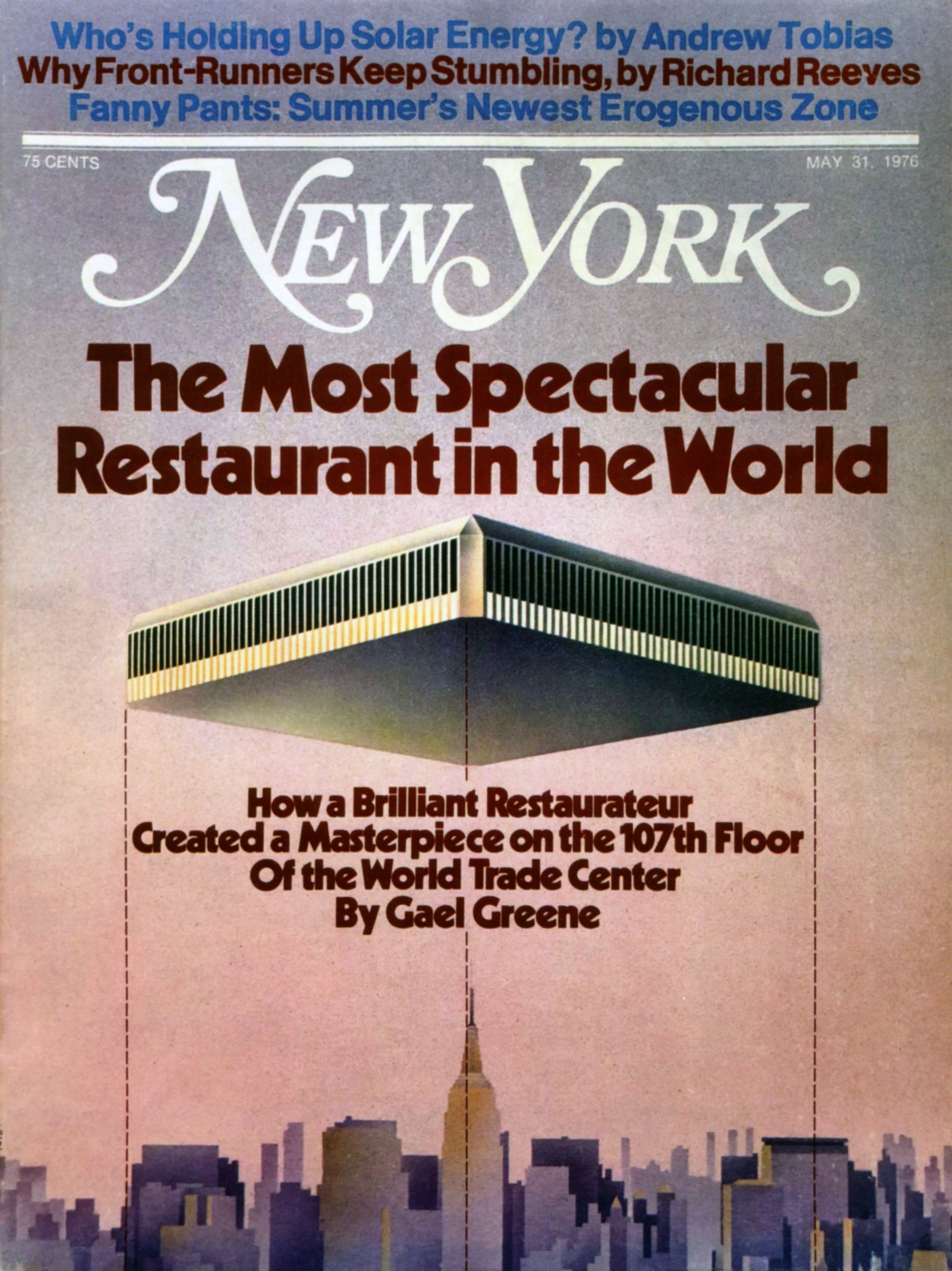

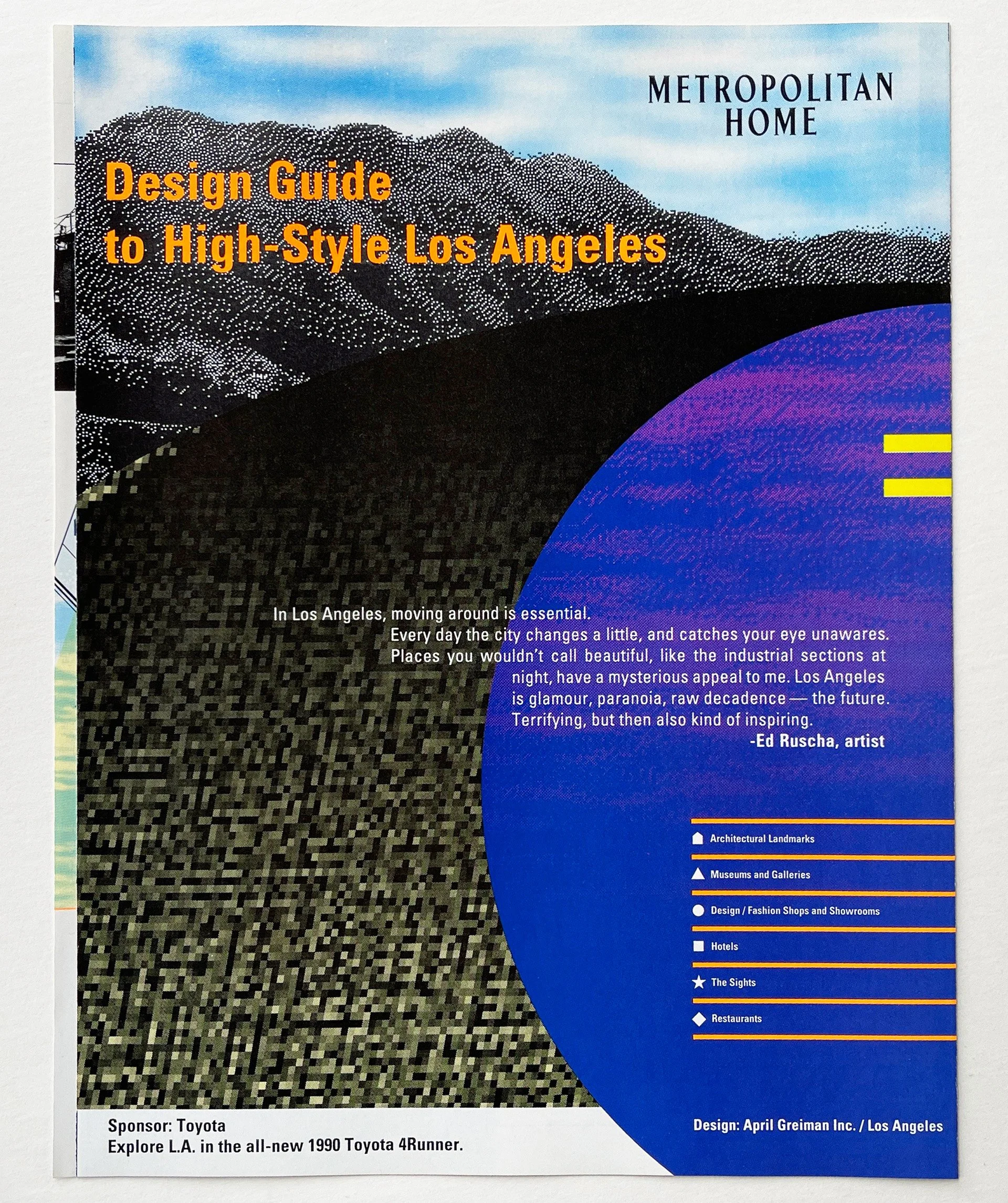

The GDP promo reel

“Sitting in San Francisco, with founders and entrepreneurs in the halls just about every day, it gets really appealing to think about yourself in one of those chairs and in one of those roles where you wonder, ‘Can I do this myself?’”

Patrick Mitchell: Let’s move on to GDP. And I don’t want to short-shrift it. So talk about the end of Wired, how that came about. It looked like you saw the handwriting on the wall. When did the idea and the conversation start for launching GDP?

Scott Dadich: Yeah, that year, that 2016 year, was really thrilling in the work that we’re getting to do with President Obama and the White House. And we had a brilliant couple of years editorially, working with Christopher Nolan, and doing the Snowden interview in Moscow, and the kind of growth we were seeing in the website—the plan was working, reintegrating Wired.com into the main newsroom and sharing leadership of that.

We crossed a billion page views—first time that had ever happened. I think quarter-of-a-billion unique visitors in one year. And a bunch of new digital revenue was coming in. So that all was working. But the industry was under, and it’s still under, even worse pressure. And at that time we were really starting to feel it.

That showed up in ad pages. That showed up in economic decision-making. It showed up in marketplace trends. And it felt really like constriction. And it felt like there were big storm clouds on the horizon. And at that time, I had been in one role or another associated with Wired for almost 11 years.

And at the same time, getting to make Abstract. I’ve got Abstract going on one side. That’s not Condé Nast. And I’ve got this work with the White House and the president on the other. And it felt like I wanted to go out on top with the Obama work, that I could not see or imagine another subject, or collaborator, or guest editor, or a thing that we could do under my care at Wired that would be more fun or more fulfilling than that.

And sitting in San Francisco, sitting in Silicon Valley, where we have founders and entrepreneurs in the halls of Wired just about every day, showing us their new product, or their new business model, or their new idea or technology or design, it gets really appealing to think about yourself in one of those chairs and in one of those roles where you wonder, Can I do this for myself? Can I choose to work with people where we go chase that idea in the way that we were trying to profile it with the subjects of Abstract?

And as we had come to the completion of that first season and the work that Morgan, and Dave, and I were doing on Abstract, we started to talk about Season Two and it really became clear that a vehicle around that needed to be built. And then the election happened. And, as part of the Obama issue, we were set to have an event at the White House to celebrate the issue coming out.

And one of the stories we had in President Obama’s issue was around the Mars series on Nat Geo that Ron Howard and Brian Grazer had created. So we’re going to have a screening of the Mars episode the morning after the election. And I was staying at The Hay-Adams, across the street from the White House, and getting prepped to go to the screening and sit with the president. And obviously that didn’t happen.

And I got an email at about 3:00 am, after the Trump result was announced, to say the president was canceling everything and I would be going back to San Francisco. But it wasn’t long after that, that I actually talked to one of my colleagues and contacts at the White House to say that the thinking that the team had been doing, the president had been doing around the Obama Foundation, had presumed launching under President [Hillary] Clinton.

And obviously that was not going to happen now. And so they needed to think about a different posture for launching the president’s next phase of work, and would I think about that. And could I help them think about communicating that and articulating a strategy there.

And it was that moment that was now we’re starting to see a pattern here where there are a couple of other activities, a couple other things that feel much more mission-oriented for me, and that I would feel really good about taking that challenge on, and stepping out of the Wired role and chasing something that was really true to what I was good at as an editor, as a designer, as a journalist, but also stretched me.

And we were really lucky at Wired that we had some help from an agency in town, run by some amazing people who had helped us articulate the Wired editorial strategy. And it just made a lot of sense that we could come together and provide both the business context and the rationale and understanding how to work with clients, but also to apply the journalistic integrity and the premise that would ultimately become The New Editorial, and put that into a consultancy.

And so that was the run-up. And it was probably a year of really deep thought, and conversations I was having with friends and colleagues, both in the industry and in technology, where there were a bunch of different possibilities, as I started to open the aperture of what could be possible after Wired. But this, I just felt, made the most sense.

Patrick Mitchell: That’s the problem. That aperture starts opening.

Debra Bishop: We know that you always have a plan, Scott. So what was your plan? How did you go about starting GDP?

Scott Dadich: A couple of us came together to do that and take on different roles and responsibilities in the running of the business. But it was also just about getting clients and providing the economic engine to start hiring people, and to start to pay rent, and to offer 401ks, and all the things that you’ve got to do as a business owner. And as someone who people trust their career with. And they trust the best years of their career with you.

So there’s a lot of pressure to that. But it was fundamentally about one of the lessons from Abstract, these big, ambitious designs and movements get created one step at a time. And it really is putting one good decision after another. And sometimes you fuck up and you need to make a different decision, or you need to alter your path. But do the best of what you can each day and with each decision.

And certainly it’s been enormously difficult, probably the most challenging thing I’ve ever taken on. But now I’m in my eighth year of it, and longer than I’ve ever held any other job. I was editor-in-chief of Wired for a little more than four years. I was creative director for five.

So this is something that I see as the rest of my career. I will not run out of challenges in this role. And we’ve been really lucky to join a collective of like-minded companies in the Kyu Collective. We work with sister companies like IDEO and SYPartners. And we’ve had a brilliant soul named Keith Yamashita join us as our chairman.

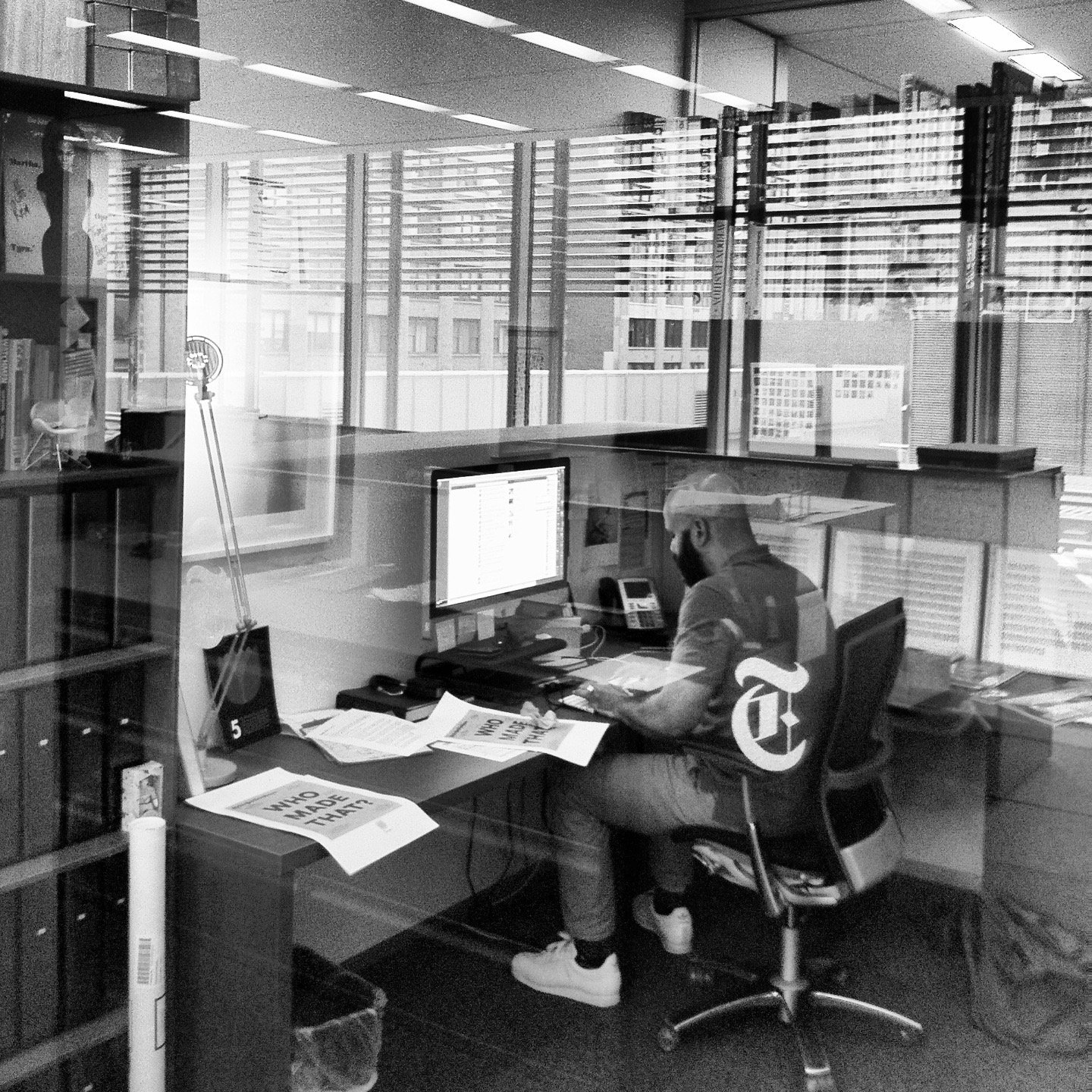

So we have the mentorship, and the guidance, and the sort of business acumen around you to chase this ambition. We acquired a digital company last year called Upstatement, also born of an editorial mindset from the newsrooms of The New York Times and the Boston Globe.

So we’ve just been doing our very best to surround ourselves with the people we can learn from and who share that same ambition, and the responsibility to share progressive and positive stories with the world in the right kinds of ways.

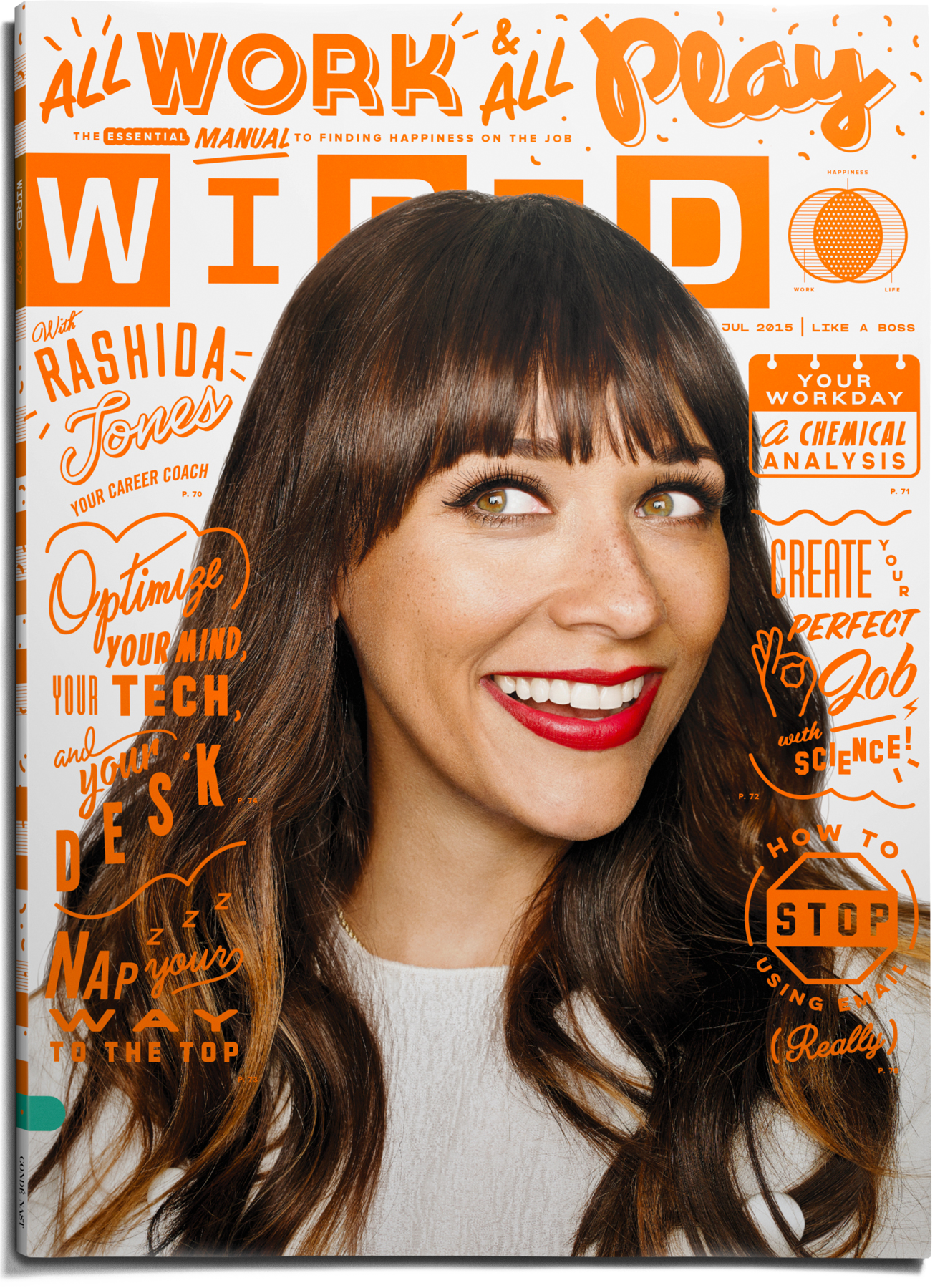

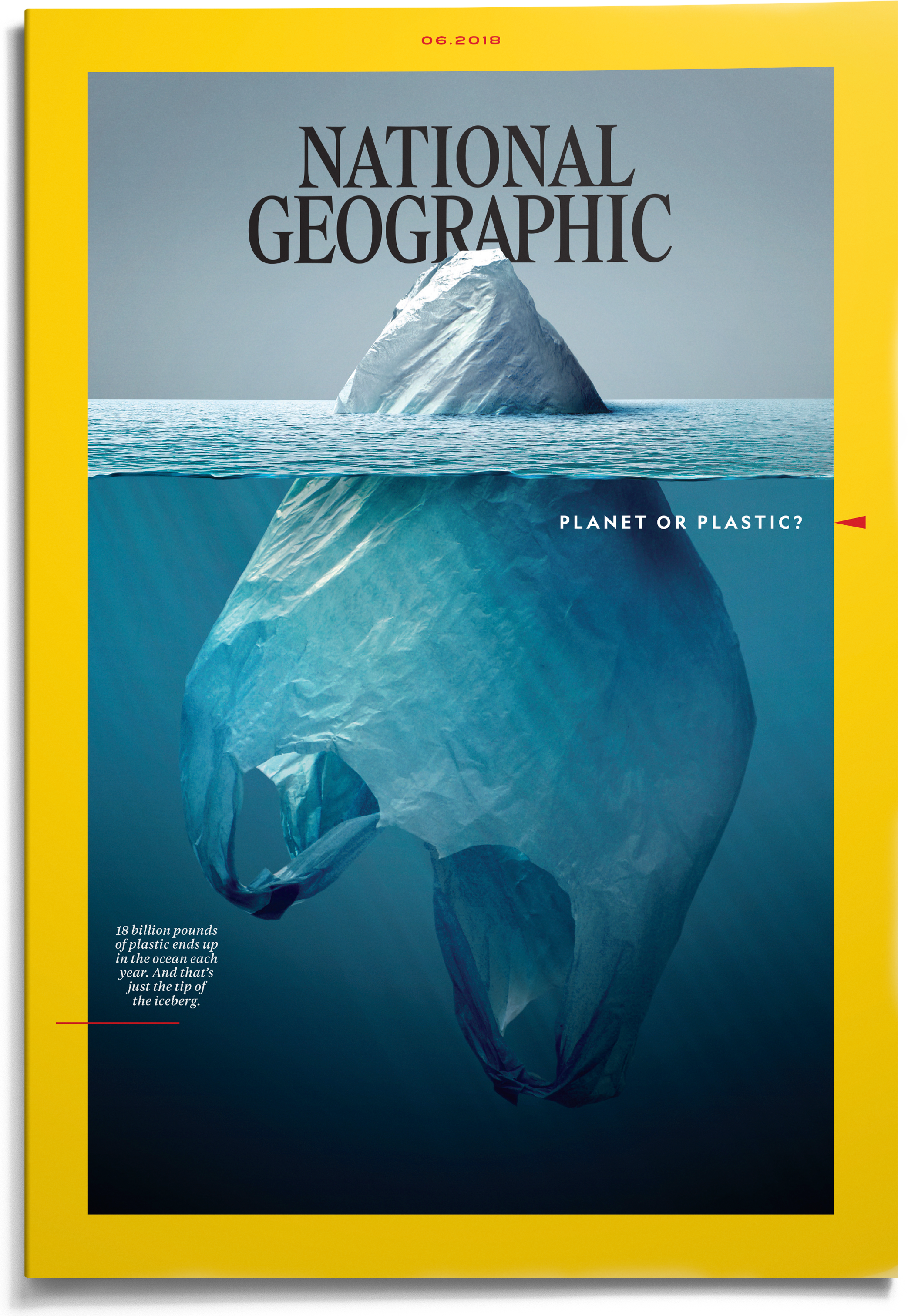

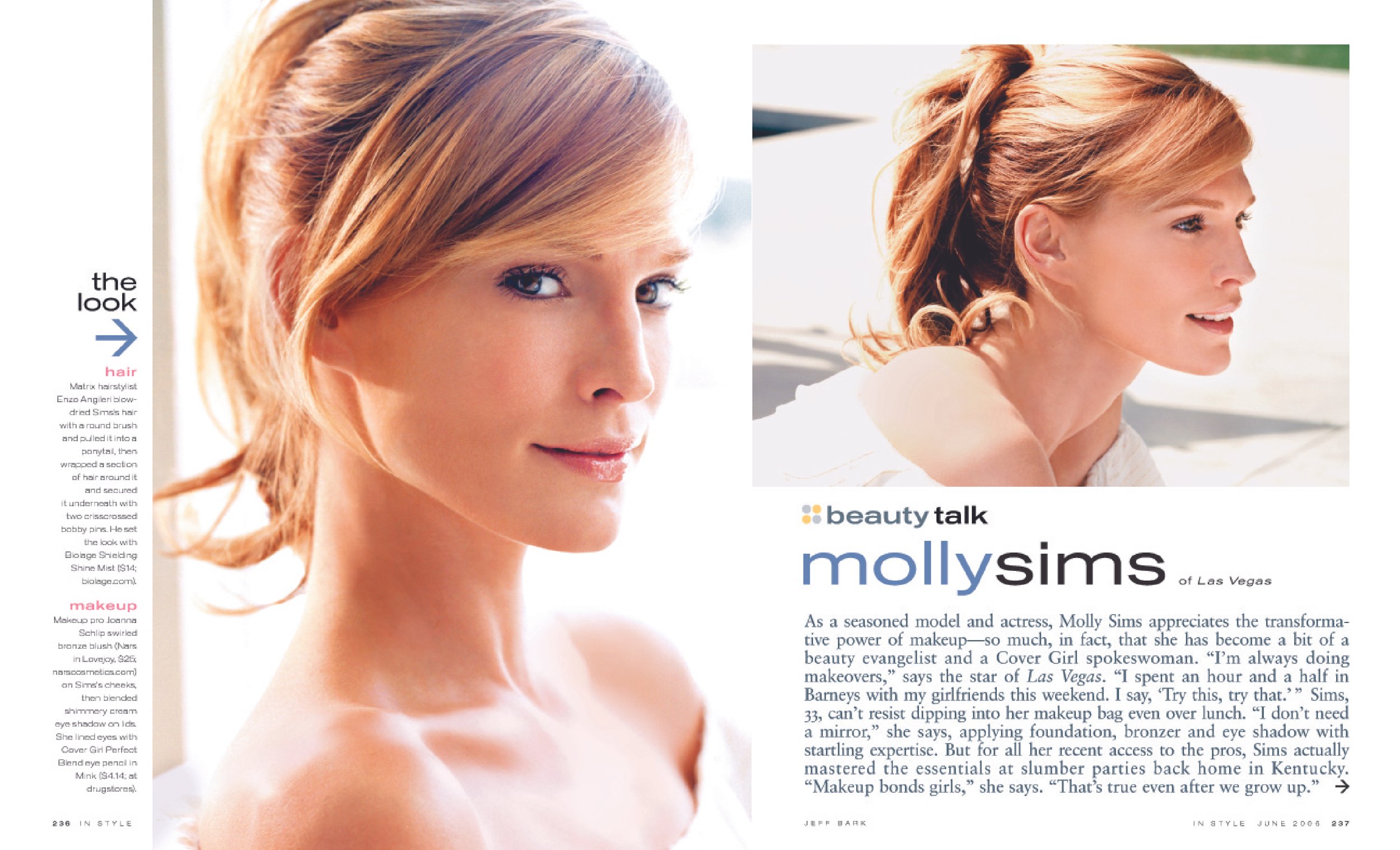

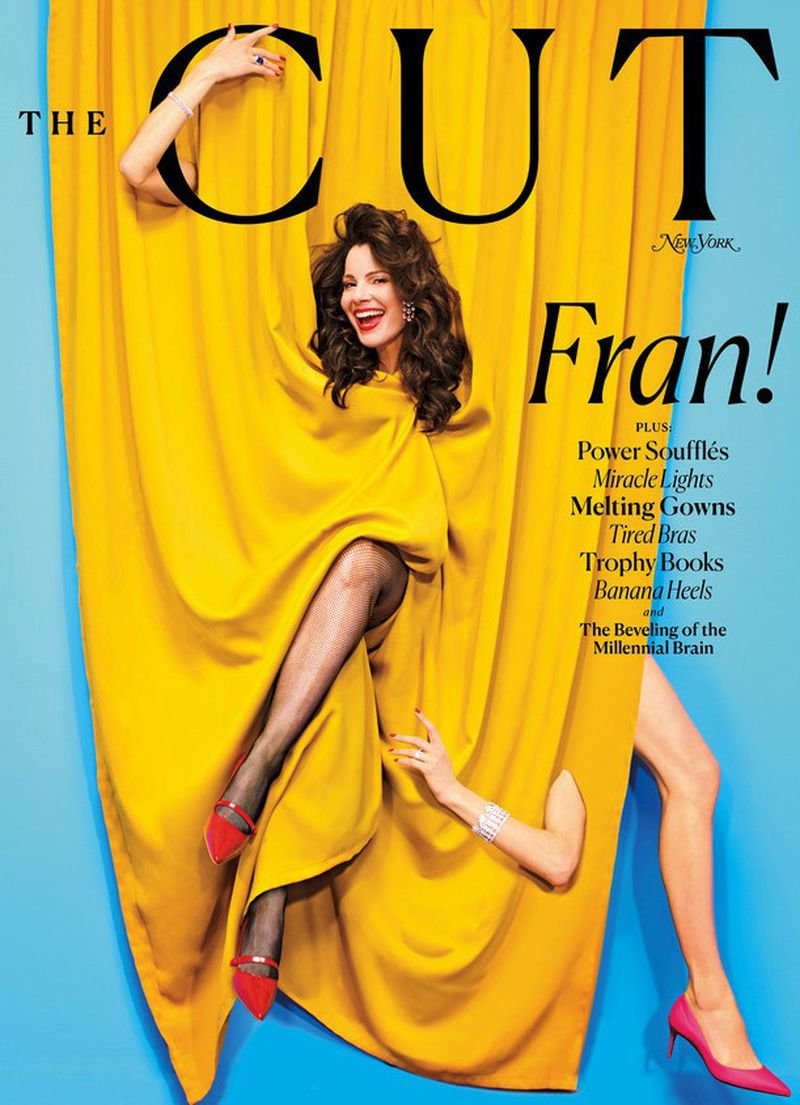

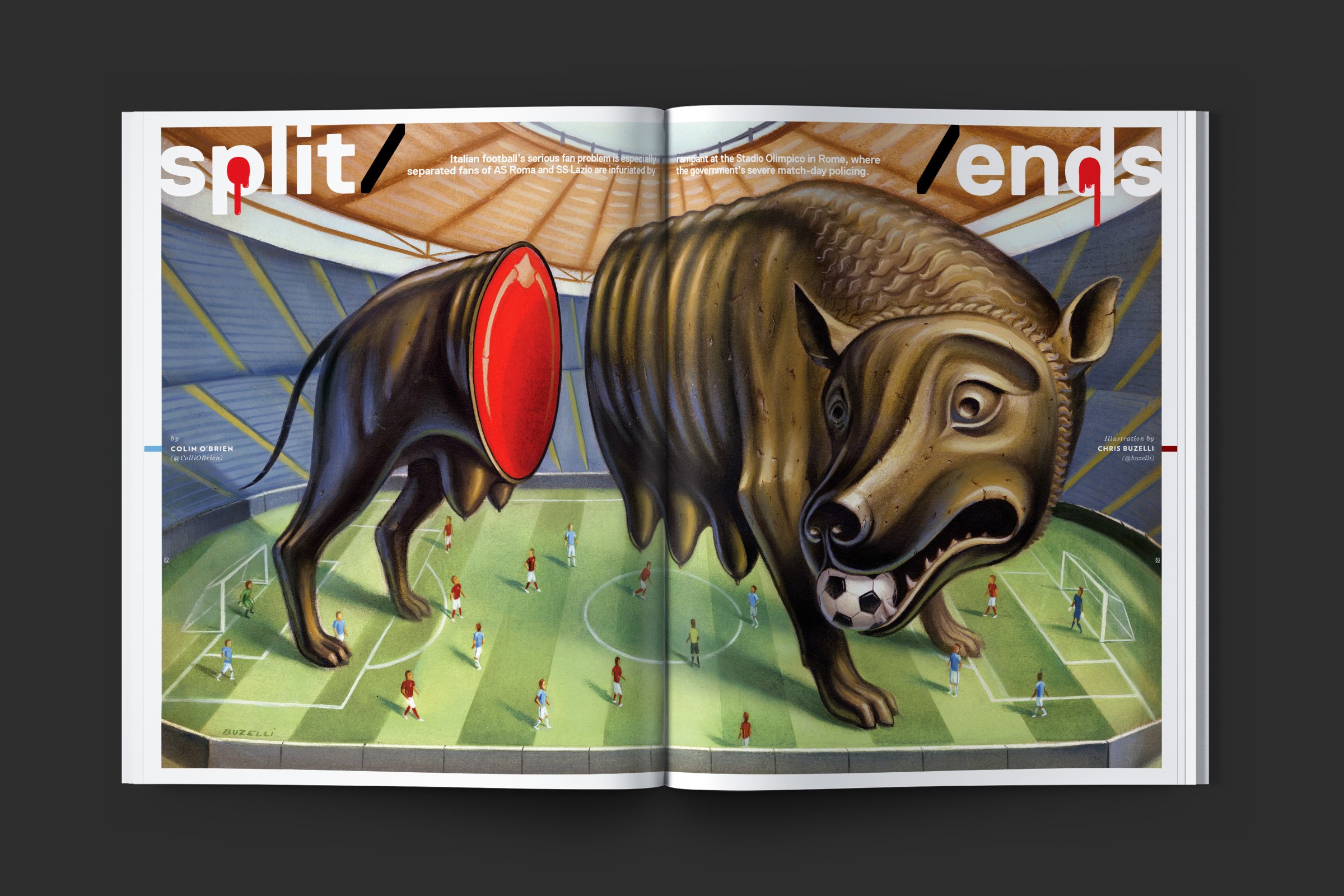

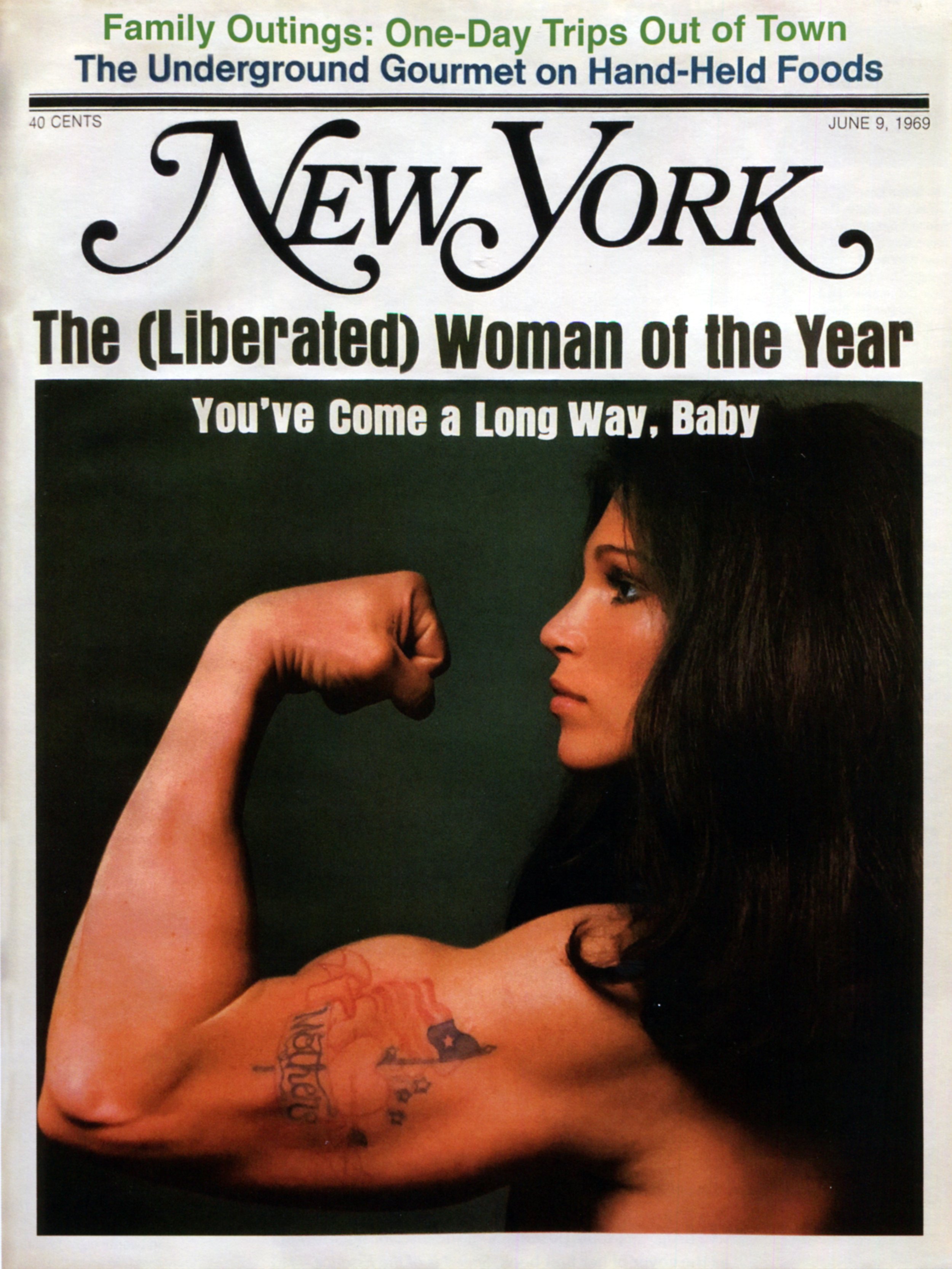

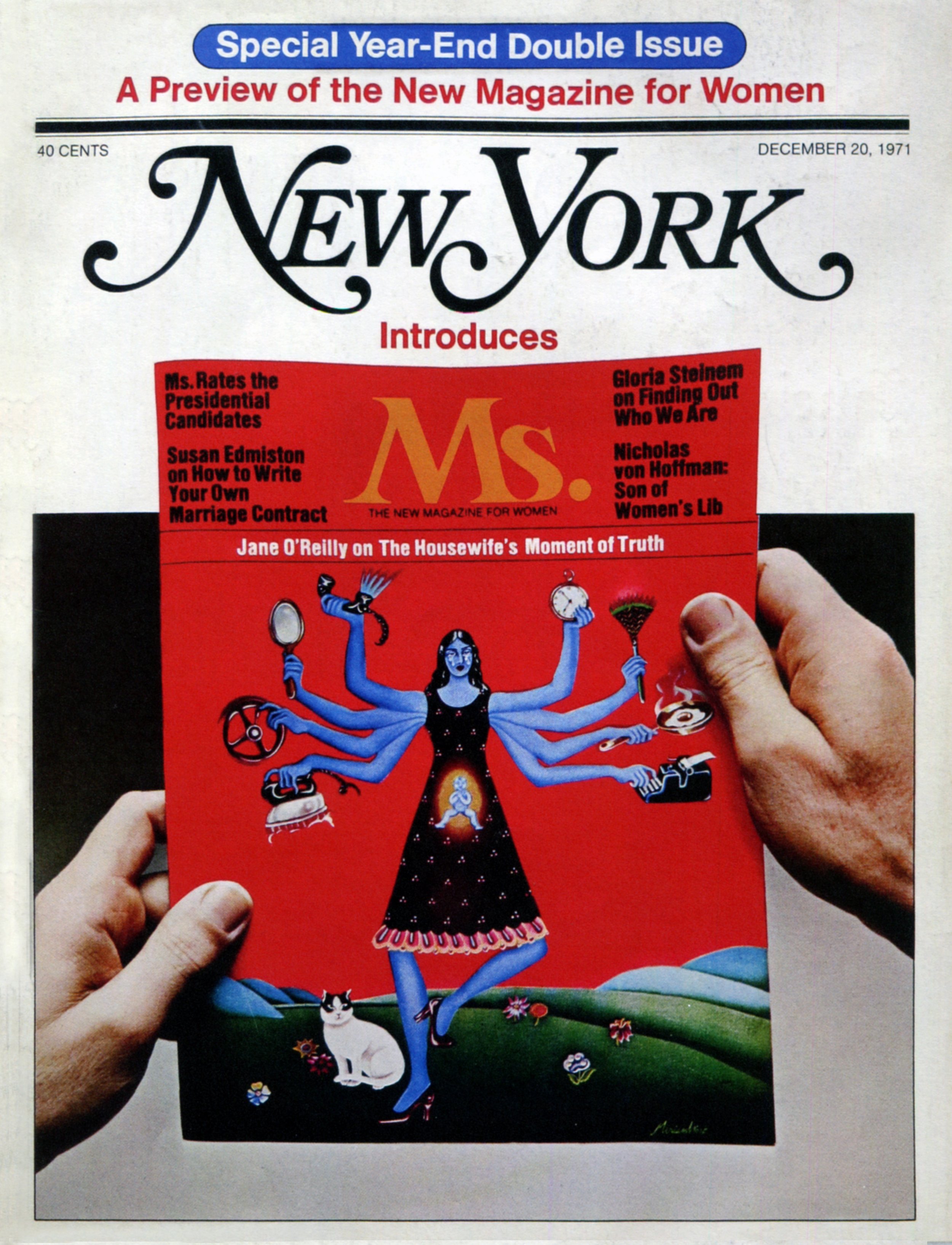

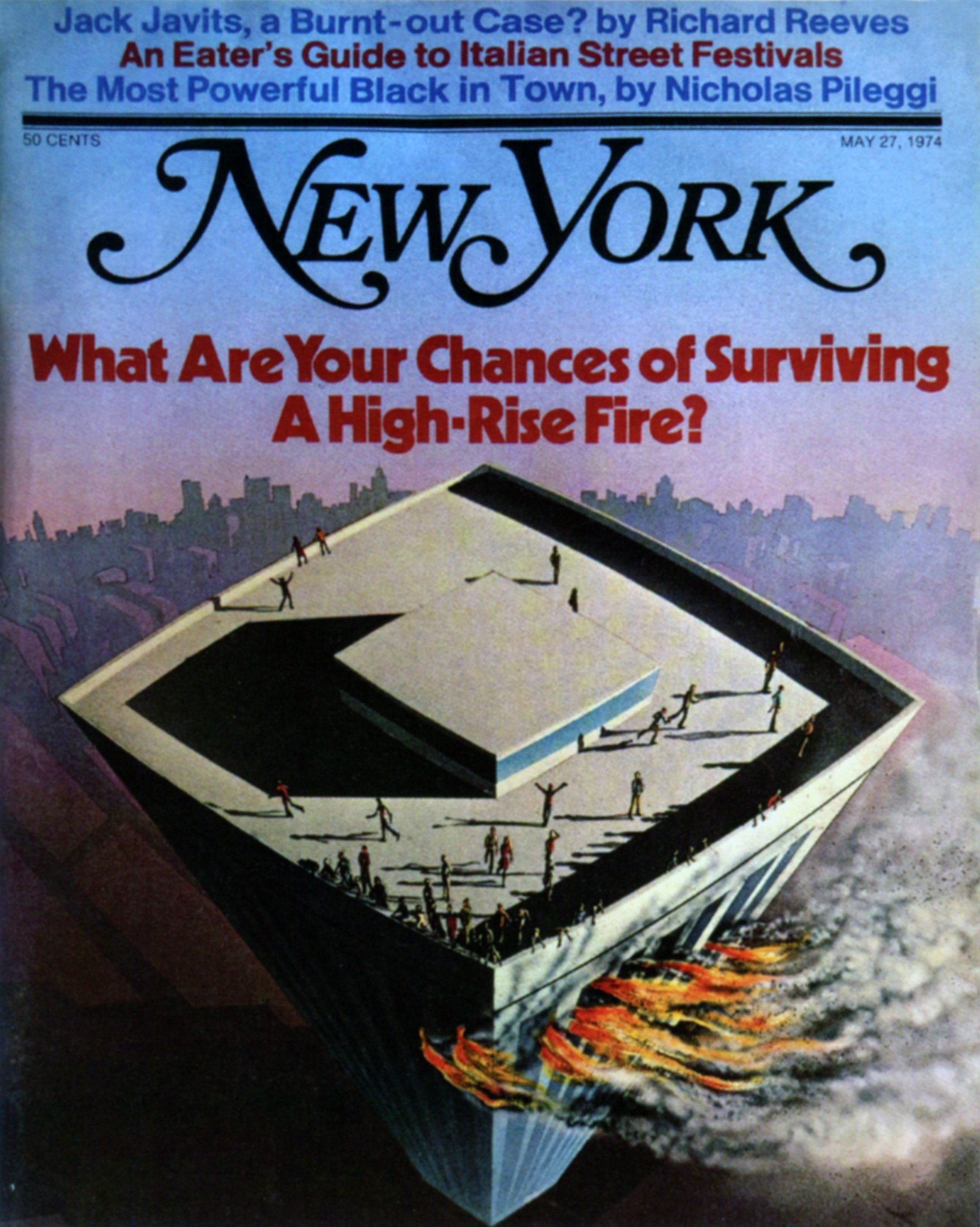

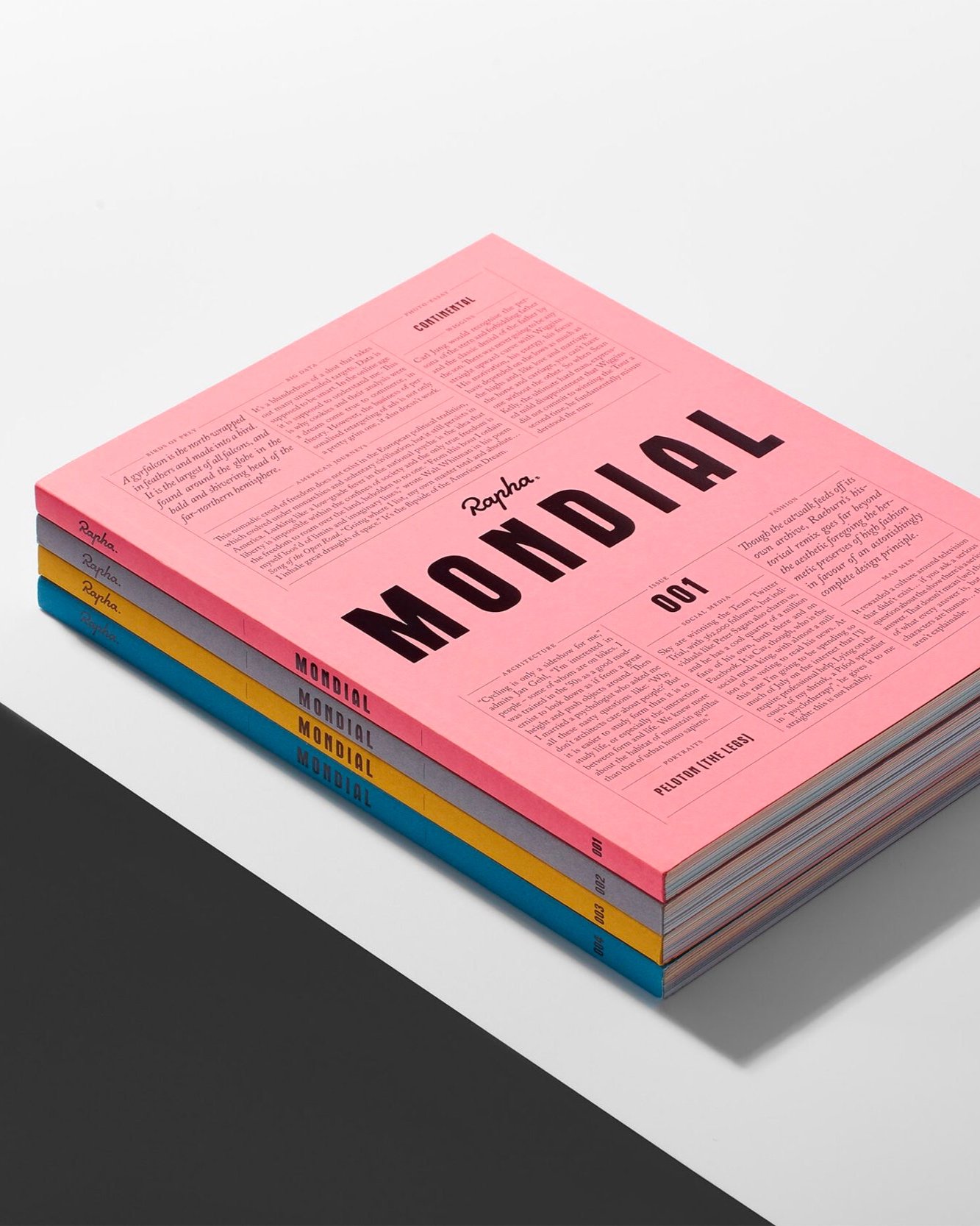

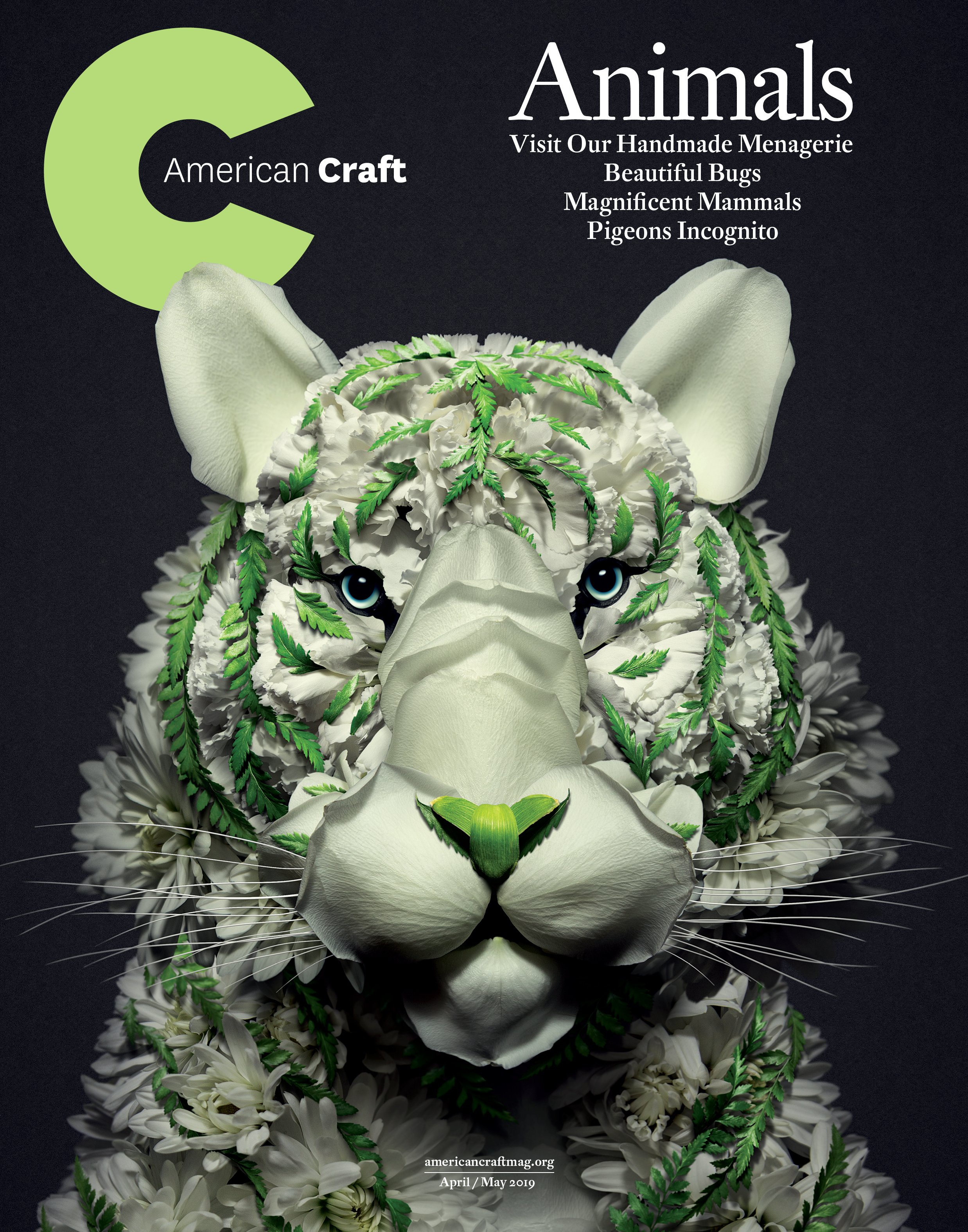

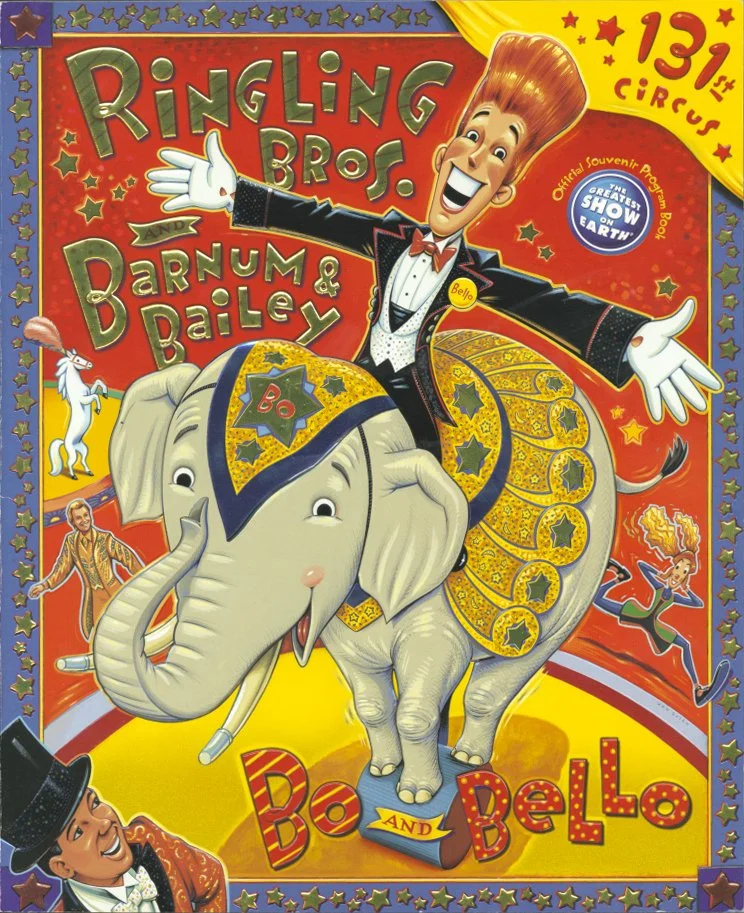

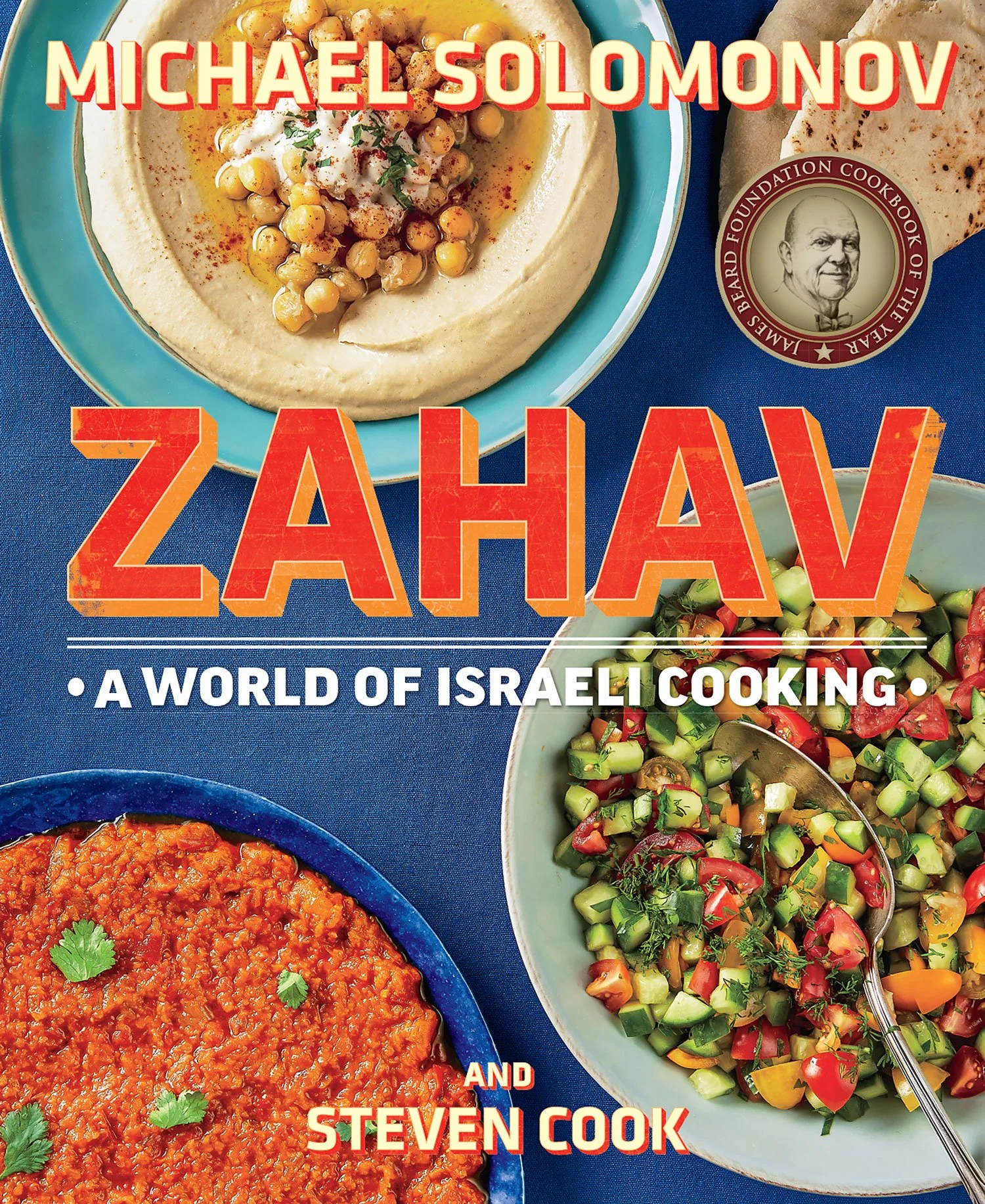

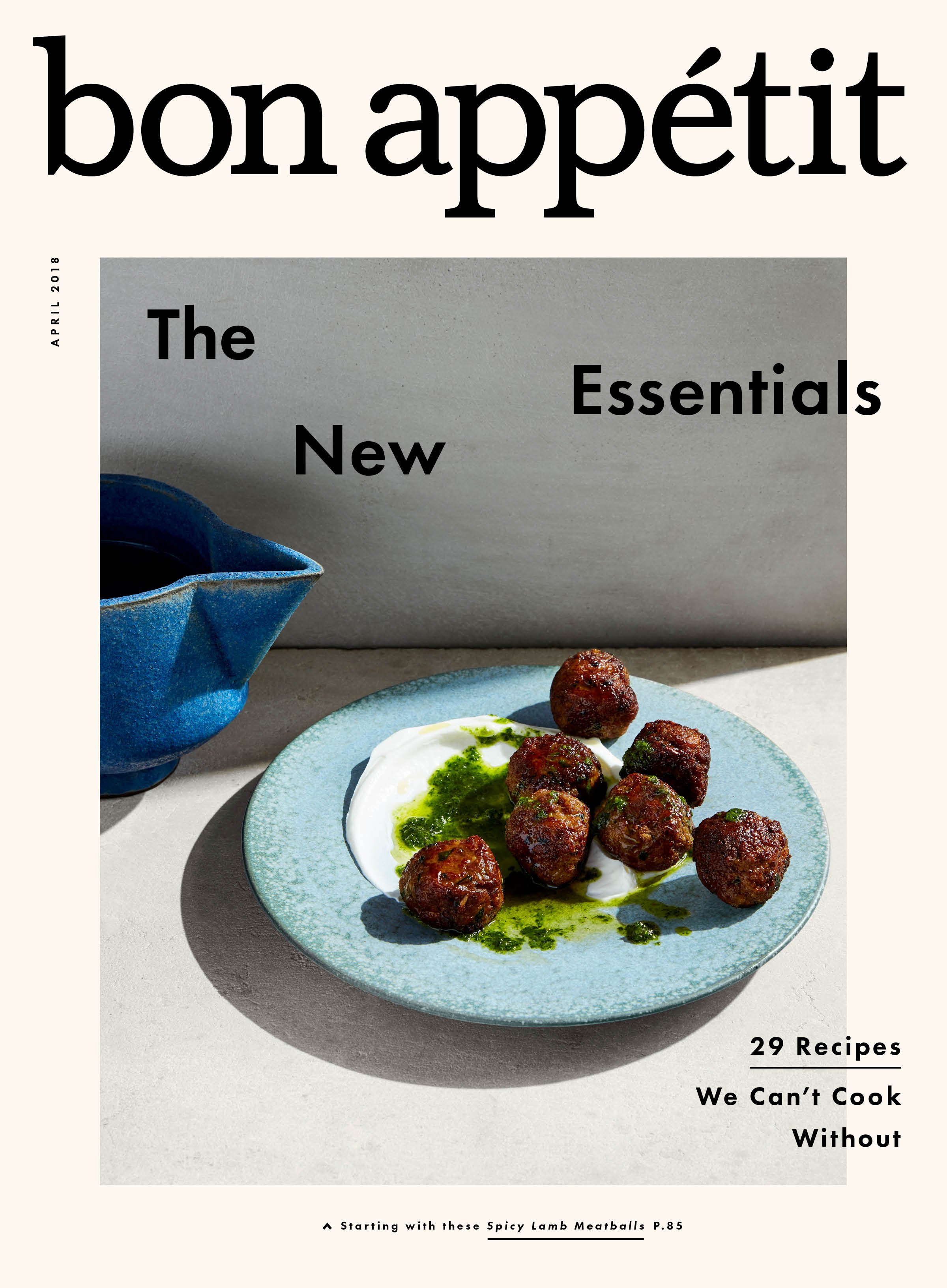

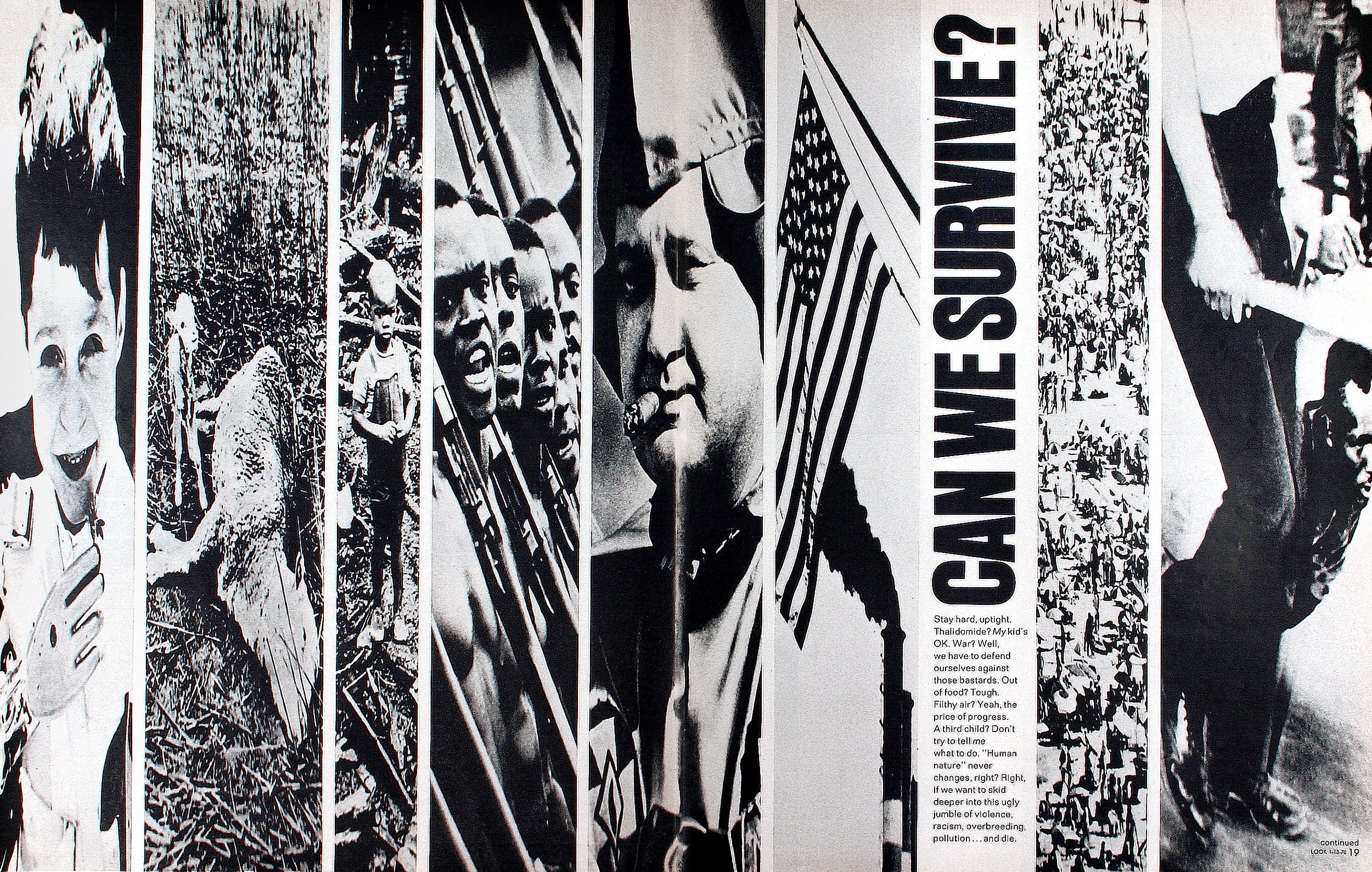

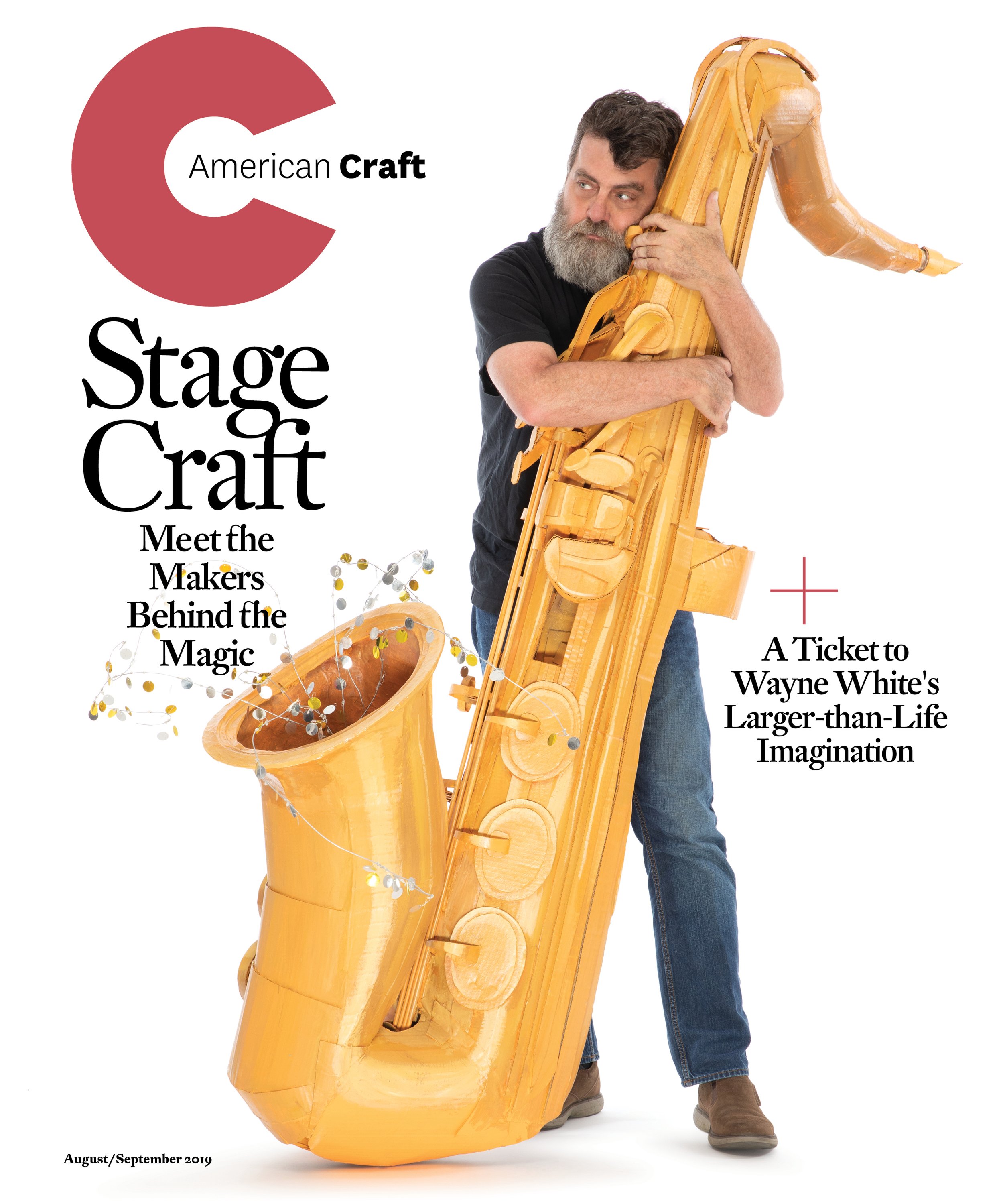

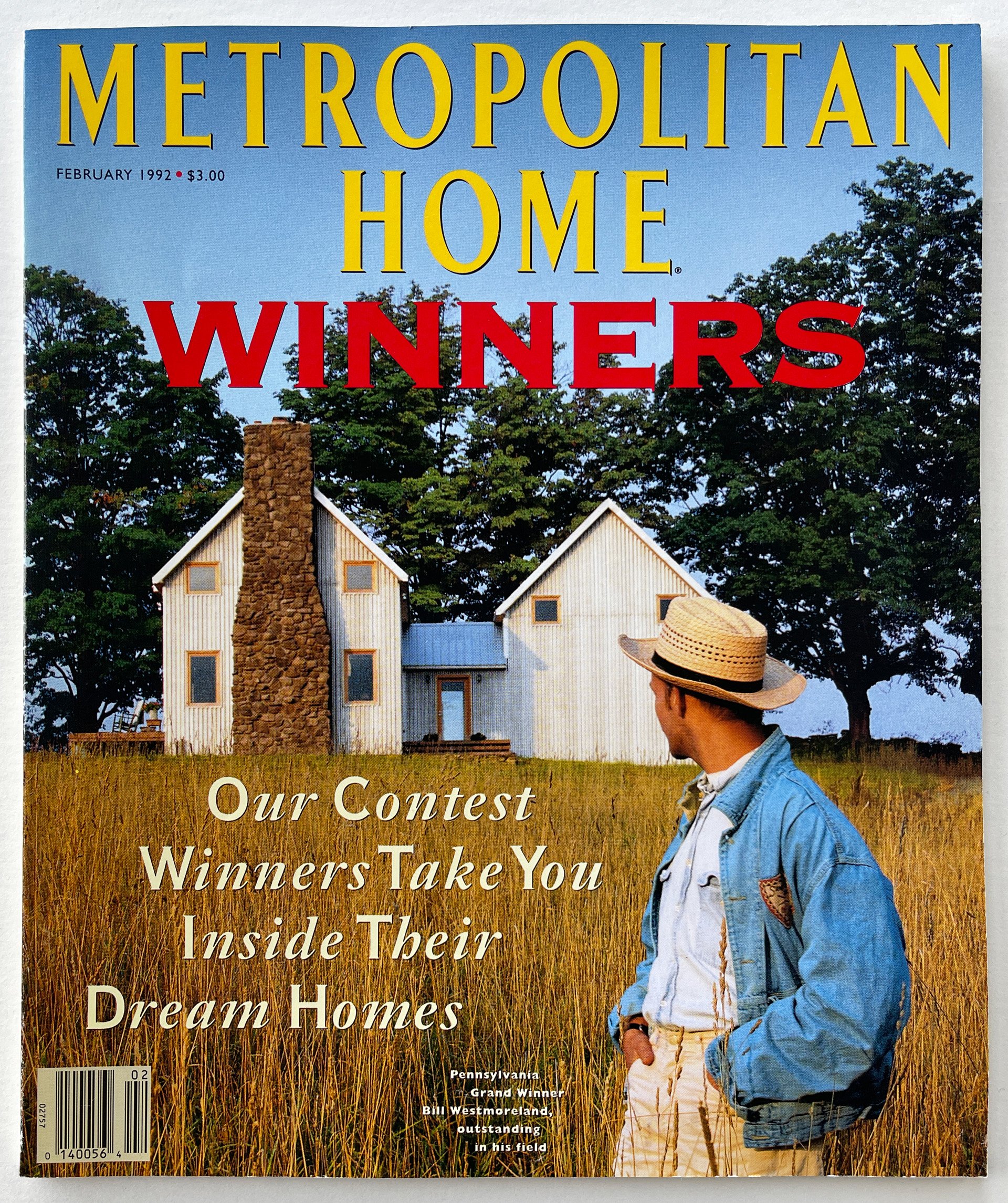

One of GDP’s early projects was a high-profile redesign/rebrand of a decidedly legacy magazine brand, National Geographic.

Patrick Mitchell: So, as you said, you joined the Kyu Collective, which is really one of those agency holding companies, right?

Scott Dadich: There are those descriptors, and I think they get well applied to organizations like WPP or Omnicom. But Kyu is very decidedly, through its founding, not a traditional holdco. It is run very much as a collective. We are all the managers of it and the leaders of it. And while we have a brilliant CEO, a guy named Michael Birkin, who has incredible experience. He was responsible for Interbrand, essentially, and basically created the concept of brand valuation, and ran a huge chunk of Omnicom. But we also organize ourselves and work together in ways that are totally voluntary. It’s just about the choices that we make rather than the sort of top down of a big agency holdco.

Patrick Mitchell: I noticed that on The New Editorial page there’s a sort of subgroup of the three of you and the slogans:

GDP: “The brand studio with an editorial mindset”

Upstatement: “A digital product studio with an editorial mindset” and

Ghost Note: “We can tell rich stories of the people because we are the people.”

So how did the three of you put yourselves together—and how do you work together? And where does this collection lead?

Scott Dadich: Great question. Thank you, Patrick. So as we started GDP, and came to understand our practice as we were writing it ourselves and came to find the successes and try to double down on those successes, it became really clear that it was just not going to be enough for us to operate independently. And that it would take too long. We wanted to accelerate our progress in some pretty meaningful ways. So that was one of the decisions around joining Kyu, to join with people that saw the world in the same way that we did.

And it’s not too long after that, that we met these three guys who founded this firm called Ghost Note, Steve Jumper, Brandon Ellis, and Reggie Snowden. And these guys founded this company about 10 years ago in Washington, DC. They’re a Black-owned business. Really, the three of them had grown up together. They had gone to school together.

And they were serving, not just Washington, DC, but building a really strong reputation doing a lot of the work that we were doing but for communities that we either weren’t of, or by, or didn’t reach, just based on our differences in background.

So we made a strategic investment in Ghost Note to have them join us. And then it was not too long after that, that we got introduced to the guys at Upstatement: Mike Swartz, Tito Bottitta, and Jared Novak. And, same thing. Like, it just felt like we had been separated at birth. And had the same kinds of backgrounds—theirs, more digitally-oriented, and from The New York Times and Boston Globe newsrooms. But with the digital acumen that is so hard to come by and that we had tried to build ourselves.

But here in the Valley, the war for talent is ongoing and quite extreme, in terms of ability to compete with the deep pockets of Apple, and Google, and Meta. We understood that we needed to look elsewhere and think about people who had businesses that were doing really well.

So we acquired Upstatement at the end of 2022, and they joined us and are in the process of doing what we do, but helping our clients really tell those stories in the forms and formats that we all deal with every day, whether that’s on a phone, or tablet, or TV screen.

Patrick Mitchell: I bet they’re bummed that they weren’t there at the time when you were doing National Geographic and Road & Track. I love Upstatement. I’ve been following them for a few years. And for the first time, I’m actually seeing real editorial thinking from a design perspective being applied to digital stuff. So kudos to them.

Scott Dadich: They have just built an incredible team. They’re in their 15th year of business. So they run a great business. And their clients come back to them, and come back to them, and come back to them. And funny enough, we had known enough about each other that they had seen the Nat Geo work. And they were jealous not to be part of it. But it was one of those sort of mutual admiration moments where we got to connect all the dots. And it’s turned out that they’re just now very dear friends and colleagues in running this bigger group.

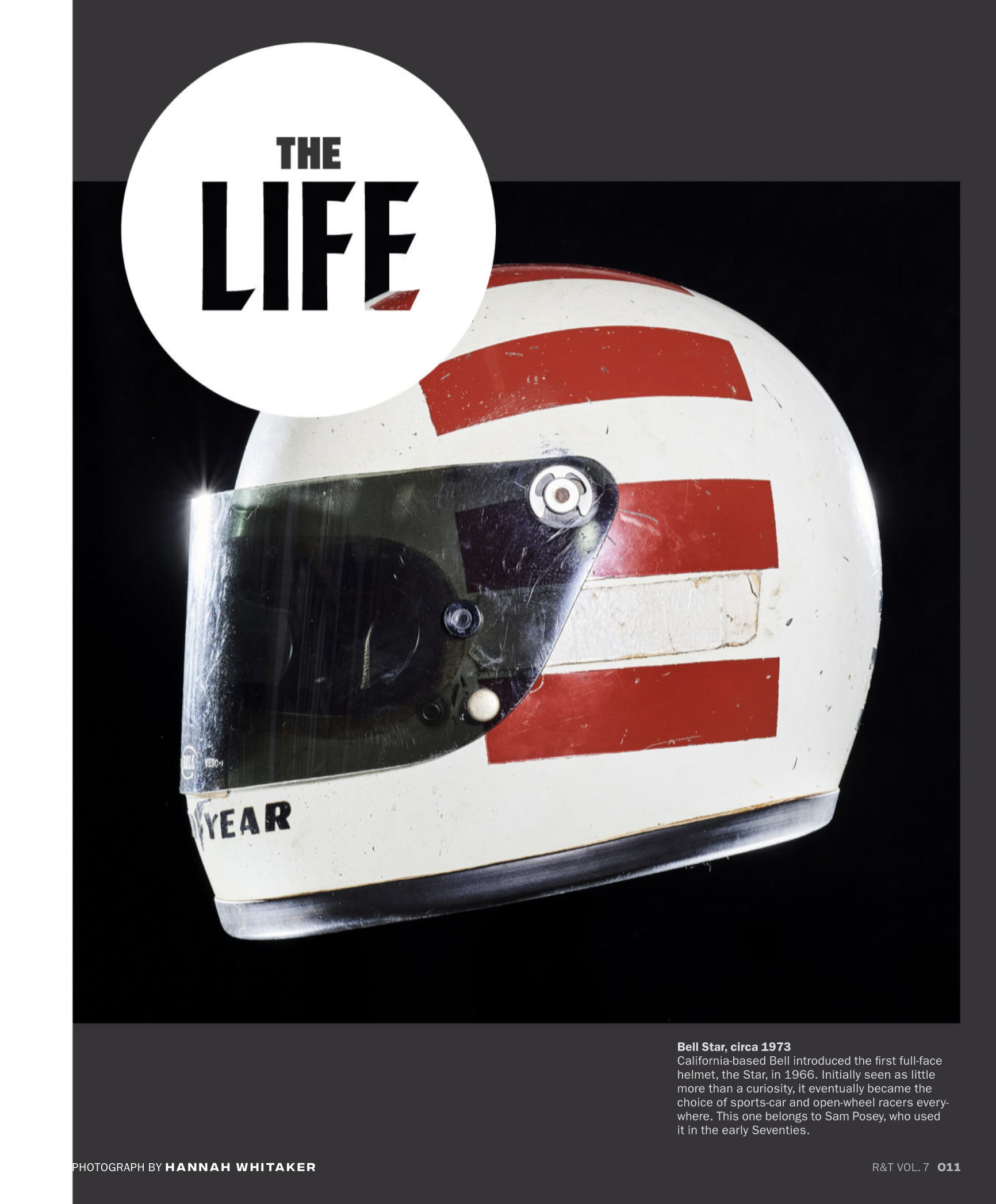

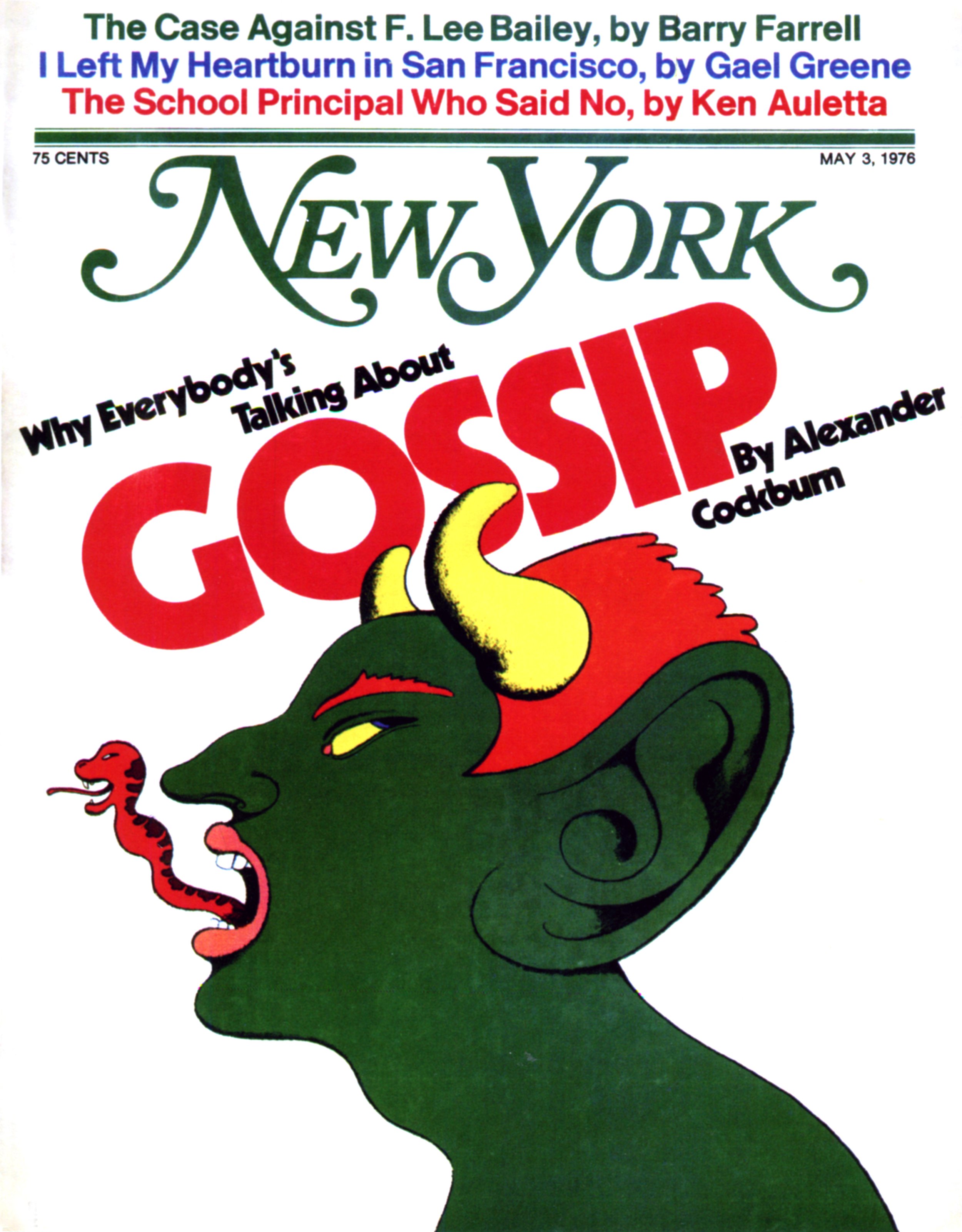

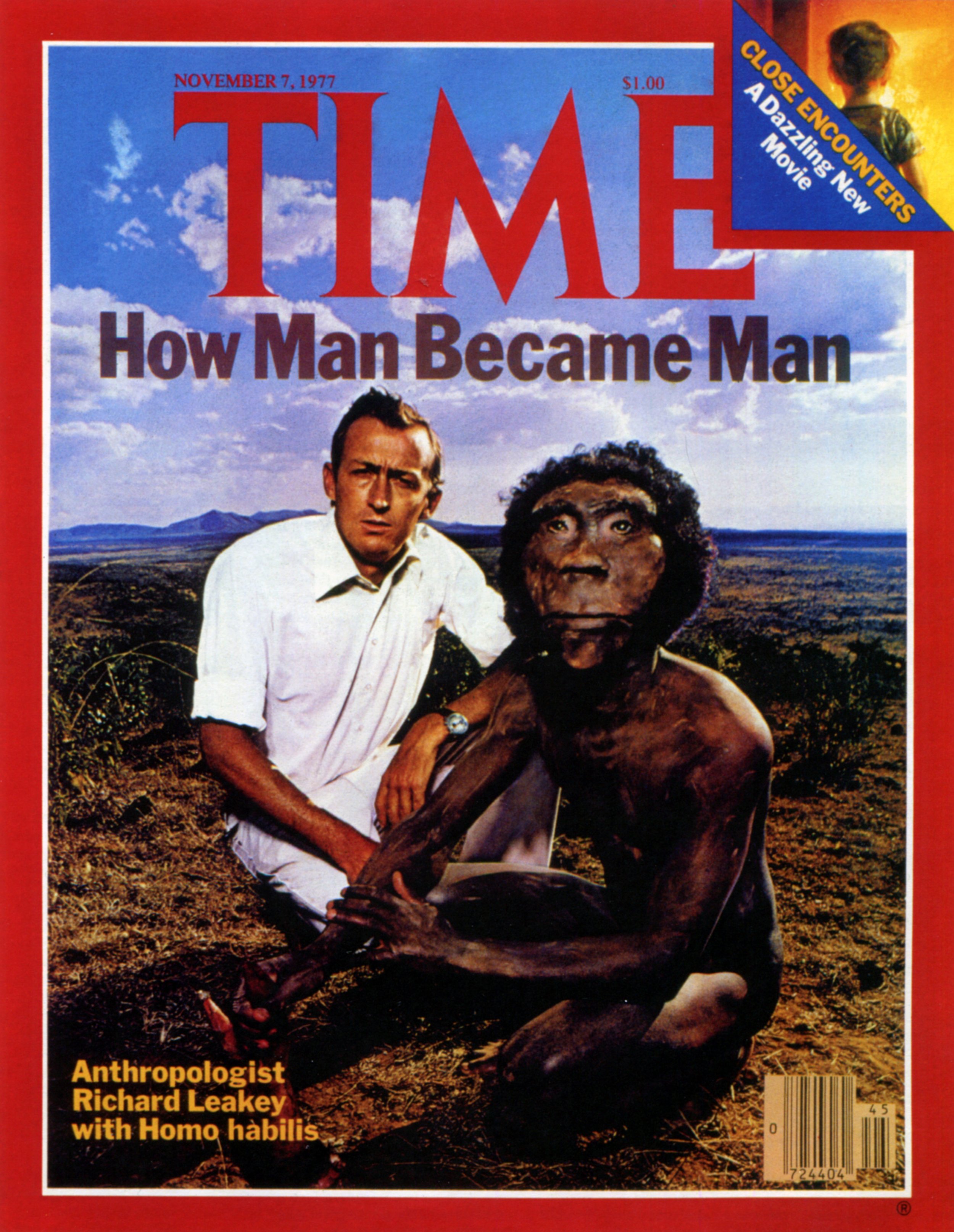

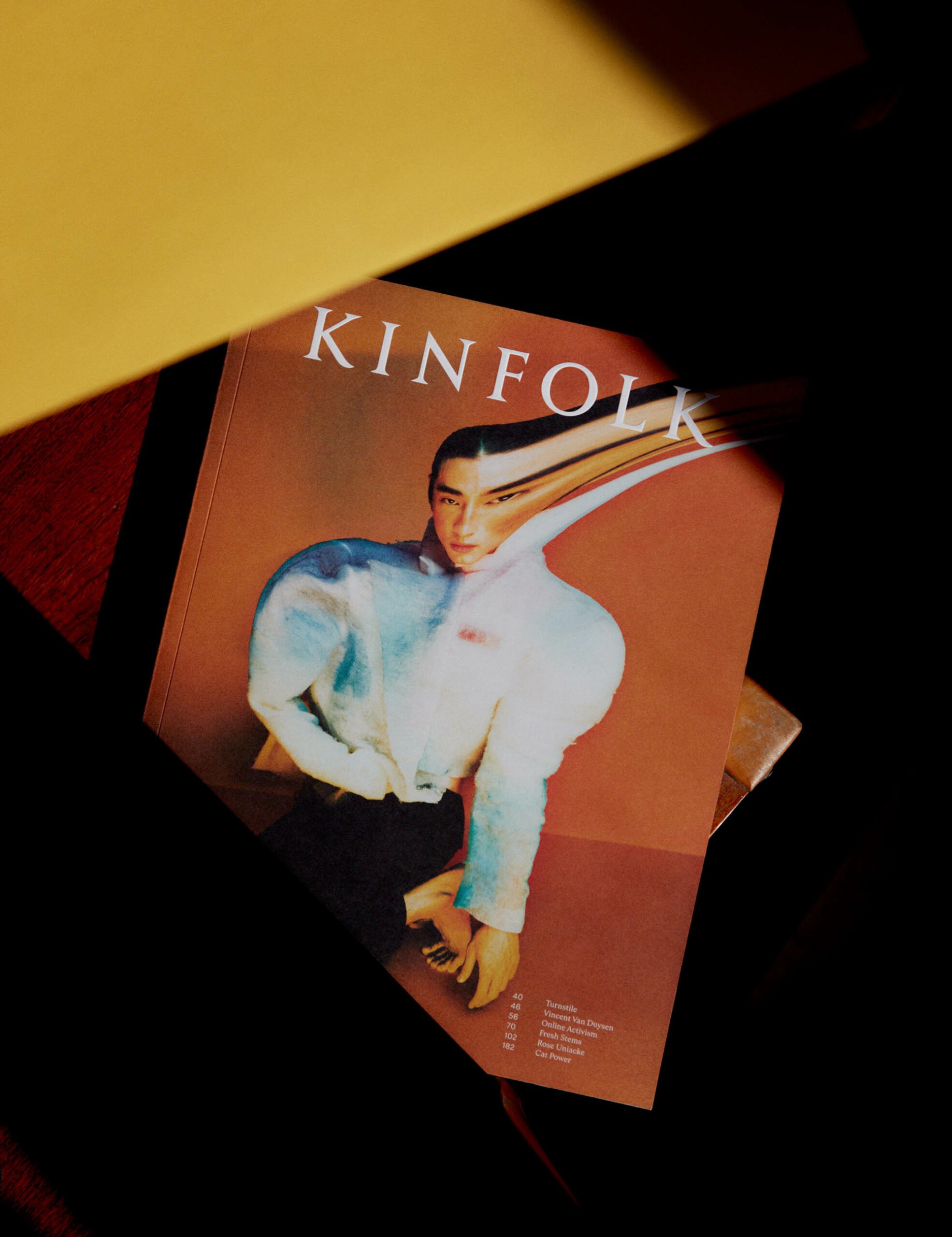

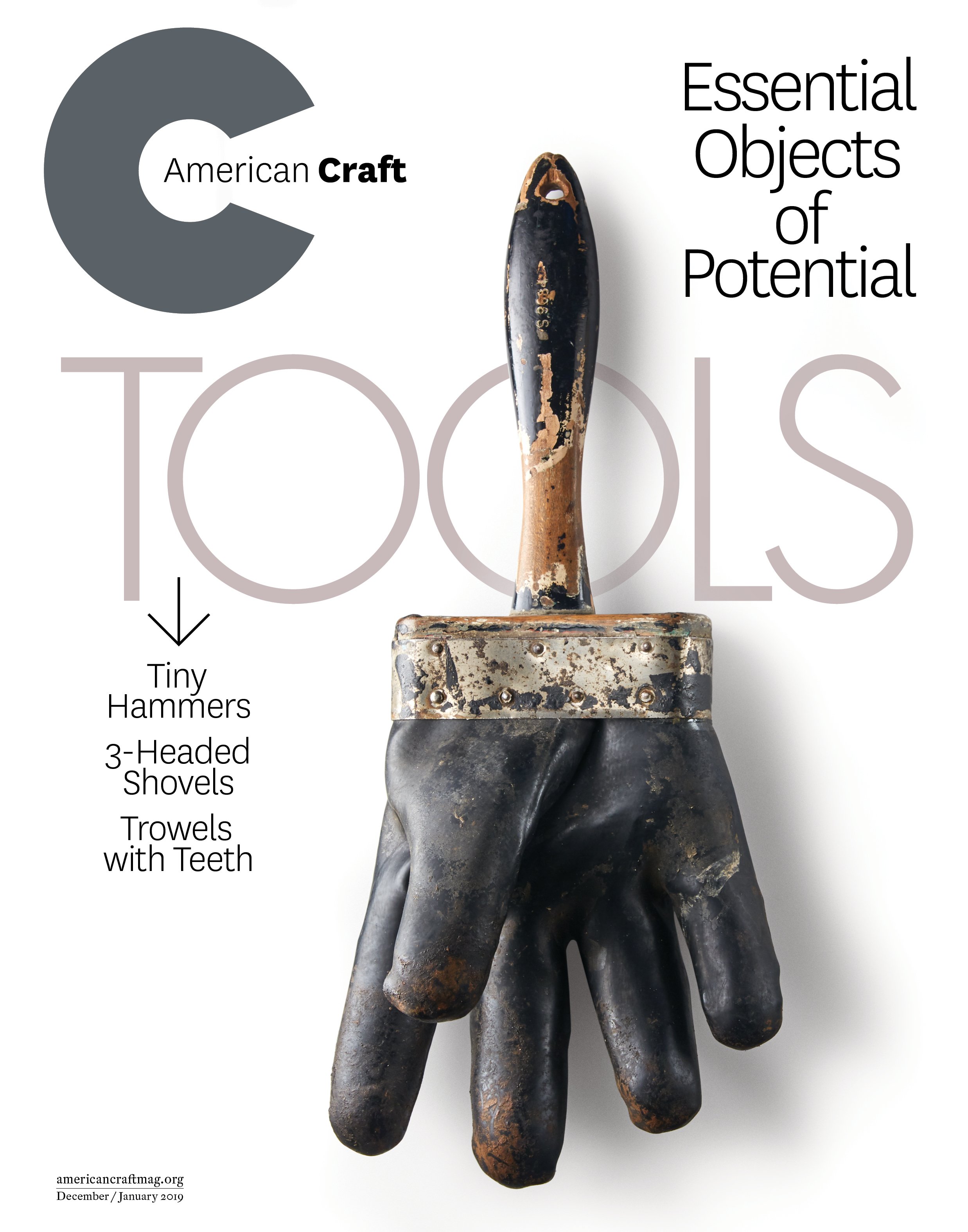

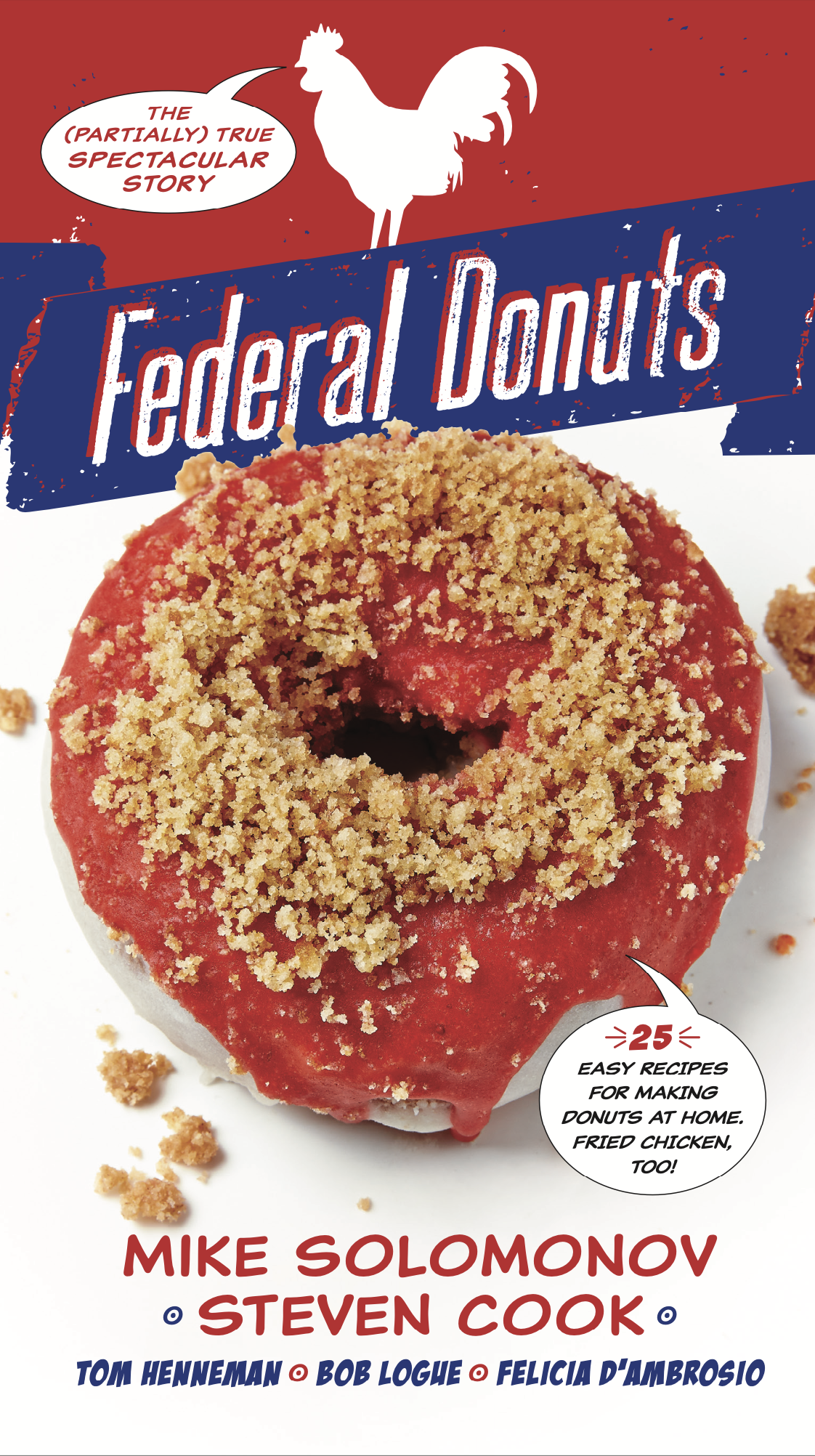

A dream fulfilled: Dadich’s passion for cars finally paid off when GDP was invited to rebrand the venerable auto magazine, Road & Track

Patrick Mitchell: Jeremy at magCulture asked you—this was now nine, almost 10 years ago—if you could see a time when Wired no longer appears in print. And you answered, “I truly can’t imagine that moment occurring in my lifetime.” We’re now on Episode 40 of this podcast and we’re not nostalgic or romantic about the future of print. But given the way you think, given your approach, given how thoughtful you are about editorial and what goes into it, how would you answer that question now? What is the ideal use of print? I don’t think it’s going away. I don’t think people are desperate to kill it, but it’s got to find a new way to play a role in our lives. Have you thought much about what that could be? What print publishers are, maybe, doing wrong? Or how they should think about their future? I have to say these indie magazines, the one thing they’ve gotten right, that big publishers should have done a long time ago, was charging what it costs to make a magazine. Time magazine, back in the day, should have been a $12 magazine for what you got out of it.

Scott Dadich: Yes. I read very few print magazines anymore. And I get sad about that. And I do find myself willing myself to do more sitting back and holding a print volume in my hands. But the fact of it is I read a ton. I probably read more than I’ve ever read, certainly that I can remember. But a lot of it just doesn’t happen in print.

But I think about the models and the people that I admire. Like I am absolutely smitten with what Yolanda Edwards and Matt Hranek have done with Yolo Journal and Wm Brown. The fact that they have figured something out there that is inspiring people—it’s inspiring me—in a way where they’re able to charge what it actually costs, and there’s value there, and that they’re inspiring people—that’s something just to applaud. And I hope that there are more people that take a lesson from what they’re up to.

As far as the bigger publishers I feel so removed from it that I feel bad even making conjectures about what is the right path to follow. I’m a bit sad to say I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about it anymore. And, I think a lot more about other kinds of problems. And so maybe that is pretty telling about where things are going to lead. But I maybe would alter my quote to Jeremy these days that maybe I could imagine a world where there isn’t a print version of Wired. That would make me pretty sad, but I could see that is a very real outcome of where we find ourselves today.

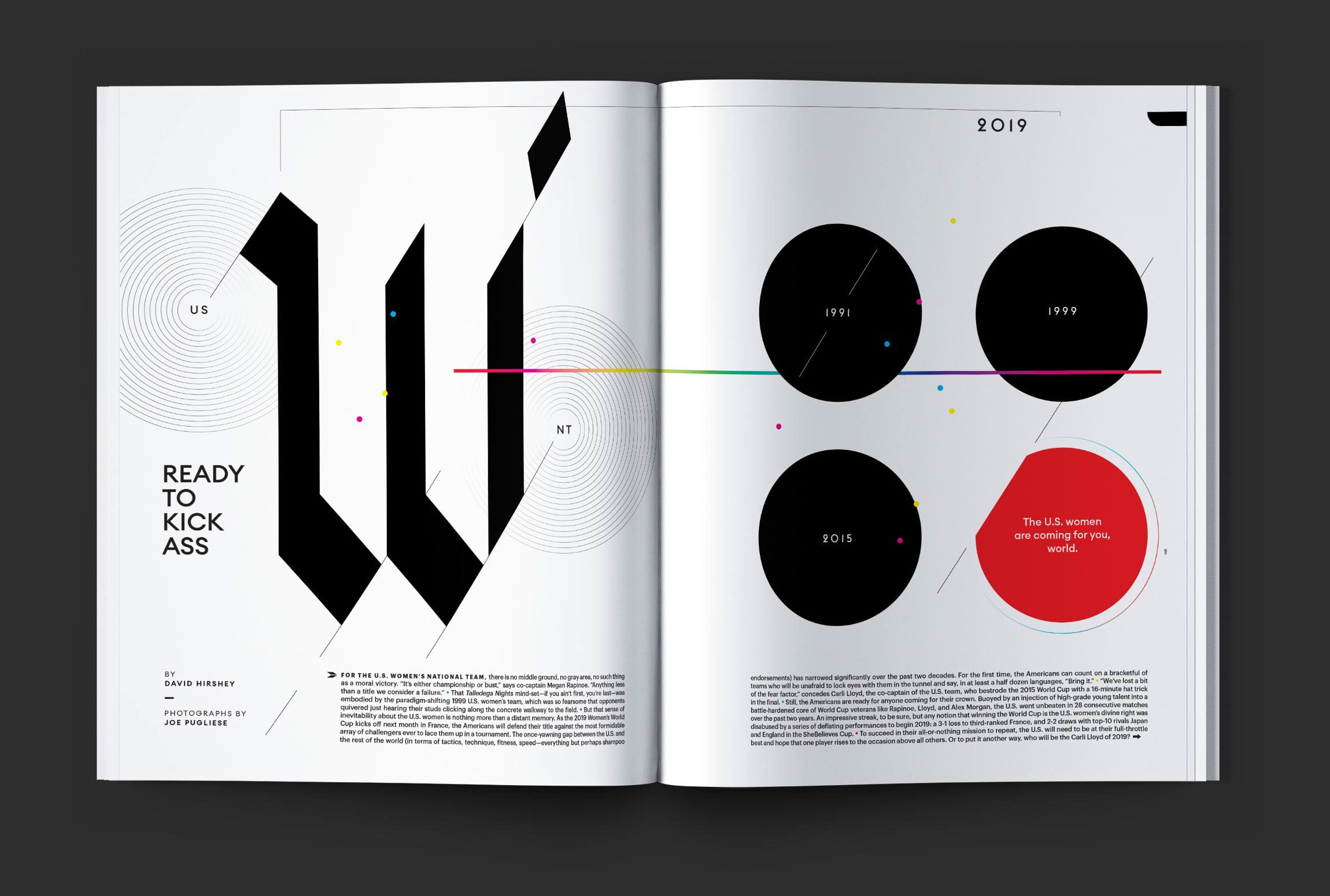

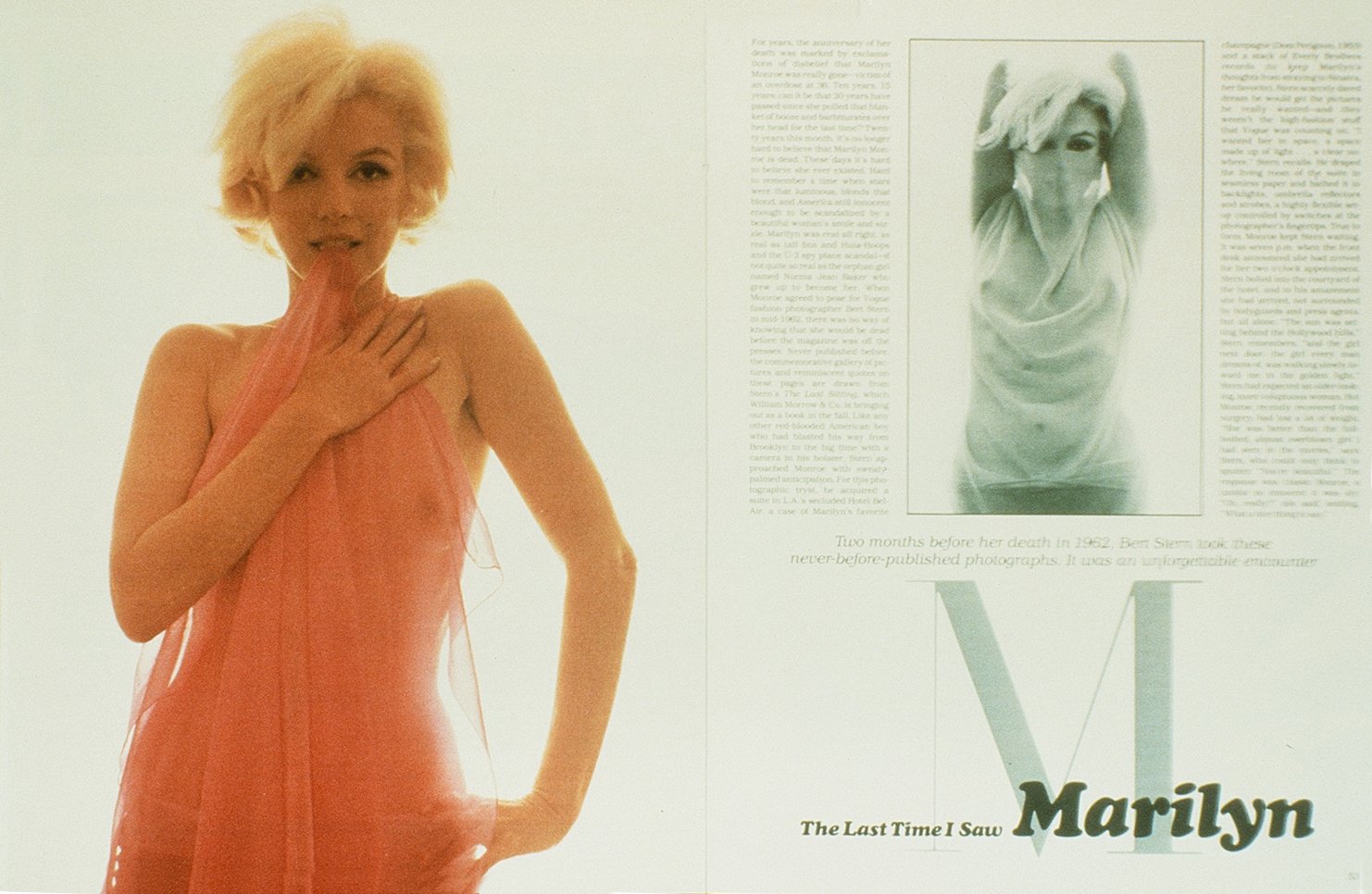

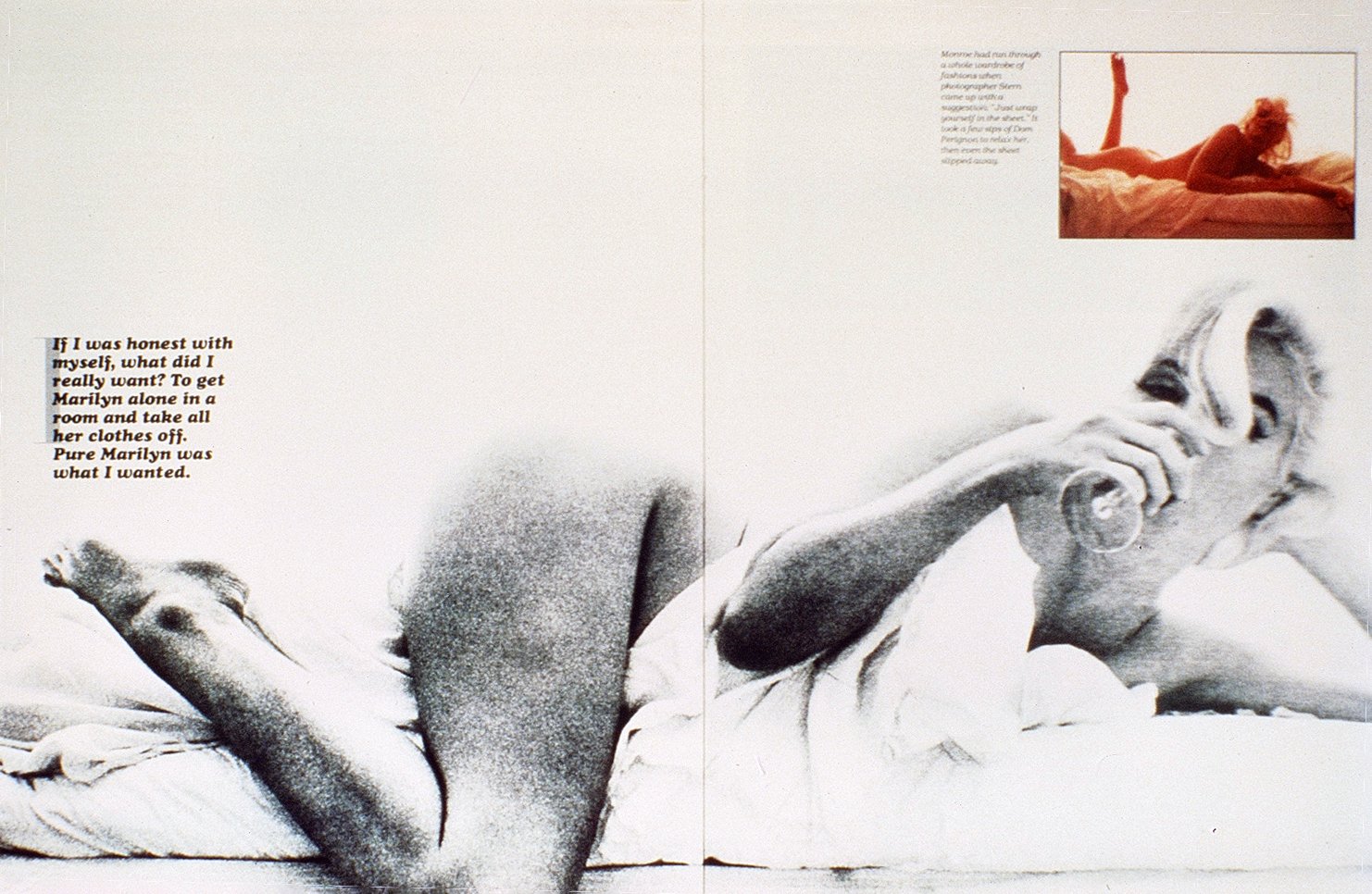

Patrick Mitchell: I think the only differentiator, the only advantage print has is large art.

Scott Dadich: What a treat, right?

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. Big photos.

Scott Dadich: I have struggled to find the medium where I can express that creative outlet in that way. Netflix came pretty close. And making Abstract certainly scratched a different kind of itch there. But there are a few things that do what a great print spread can do.

Patrick Mitchell: Okay, let’s get to the PID Billion-Dollar Question. The windup is that a billionaire of your choice has deemed you worthy of an unlimited amount of money, a billion or more, with one caveat: that you have to create and produce something in print. What would you make?

Scott Dadich: So easy. So exciting. Abstract Journal. I have wanted, since the earliest days of Abstract, to put its lessons into print. It is just such a voluminous pathway. There’s just so much to be able to do there because of the diversity of design decision-making, of the creative pathways that these people pursue.

So much inspiration, so much hope, so much optimism in what they get to do. And I could think of an almost endless supply of stories to tell. And that they’d be visually compelling, and thought-provoking, and challenging in ways I think that we can’t even conceive of.

So that’s always been the dream. And the Abstract community is something that’s still—I feel so lucky—it inspires me every day. And I just think there’s no shortage of work that we could do with Abstract Journal.

For more on Scott Dadich, visit Godfrey Dadich Partners online.

Related Stories

Back to the Interviews

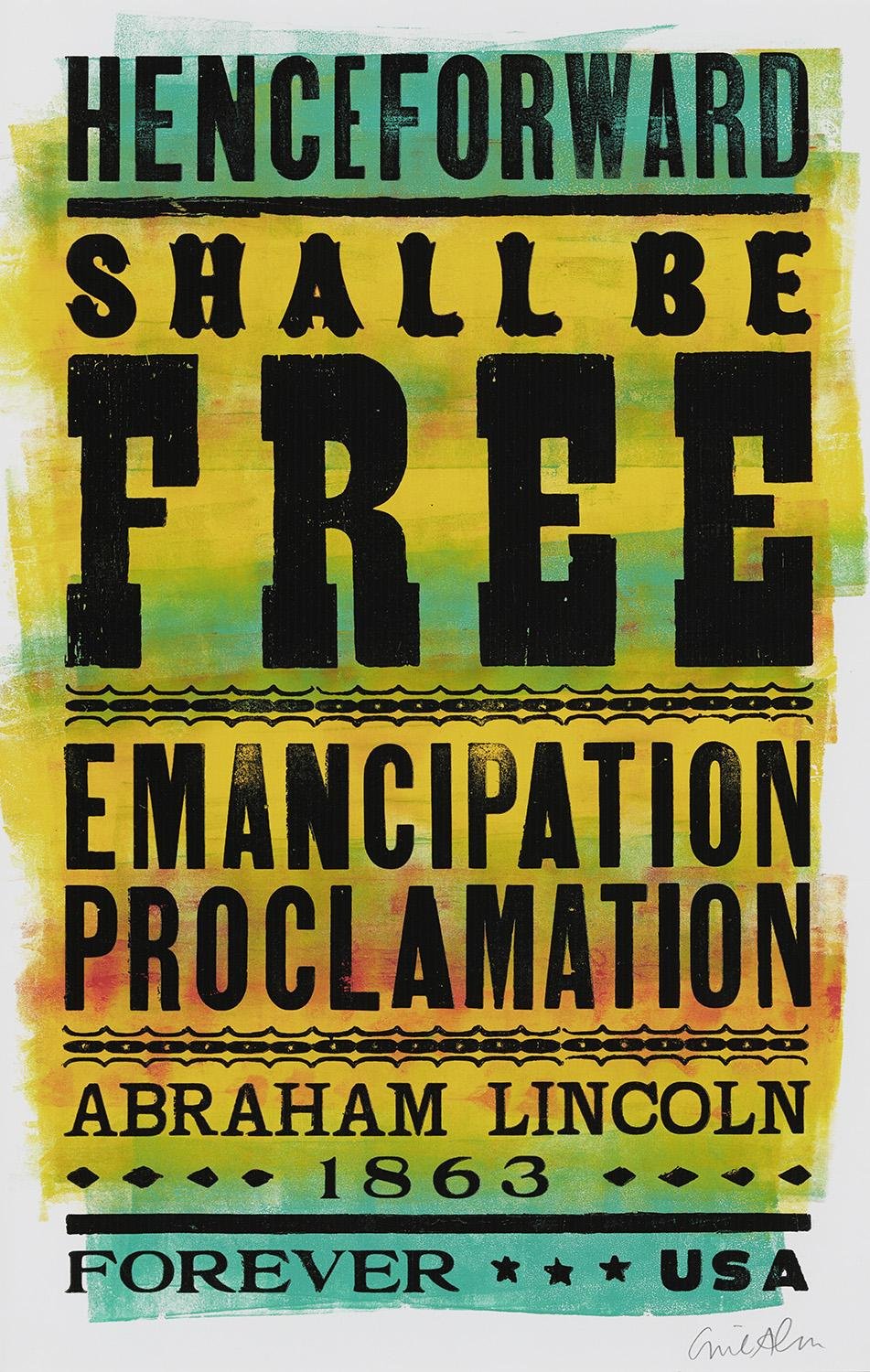

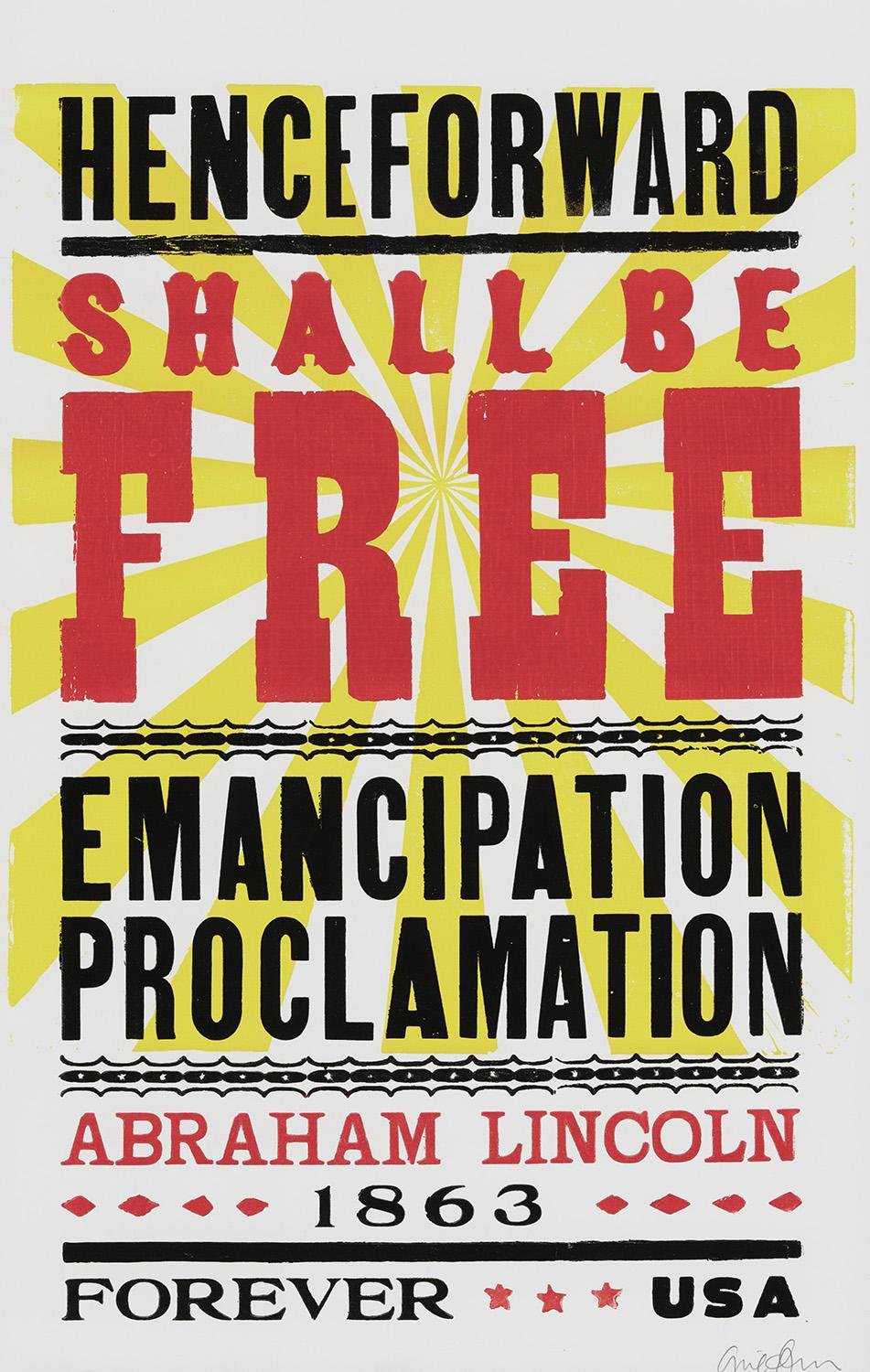

What’s Red and Yellow and Orange All Over?

A conversation with illustrator and author Edel Rodriguez (Time, Mother Jones, Der Spiegel, more)

A conversation with author and illustrator Edel Rodriguez (Time, Mother Jones, Der Spiegel, more).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT MOUNTAIN GAZETTE , COMMERCIAL TYPE, and LANE PRESS

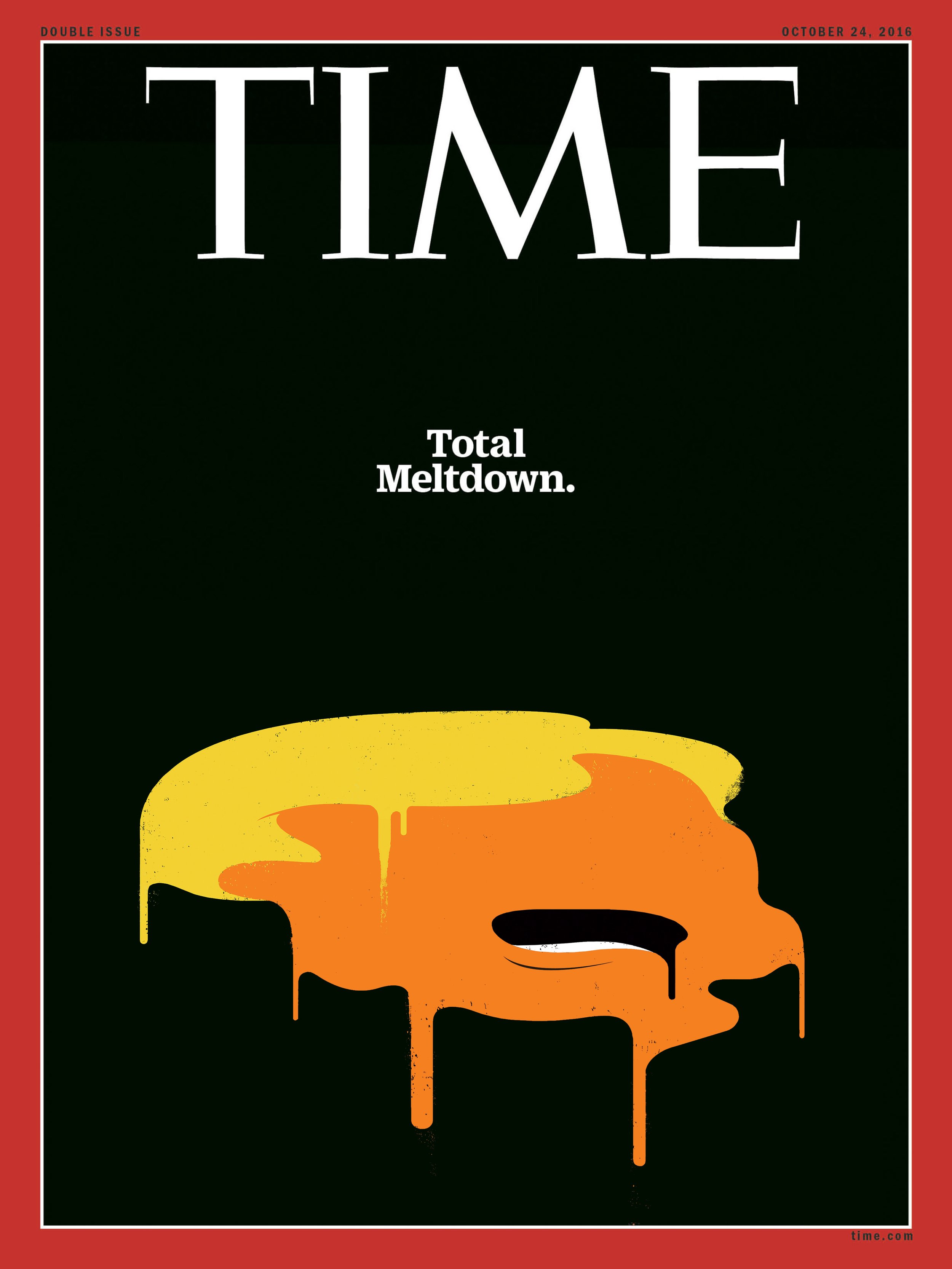

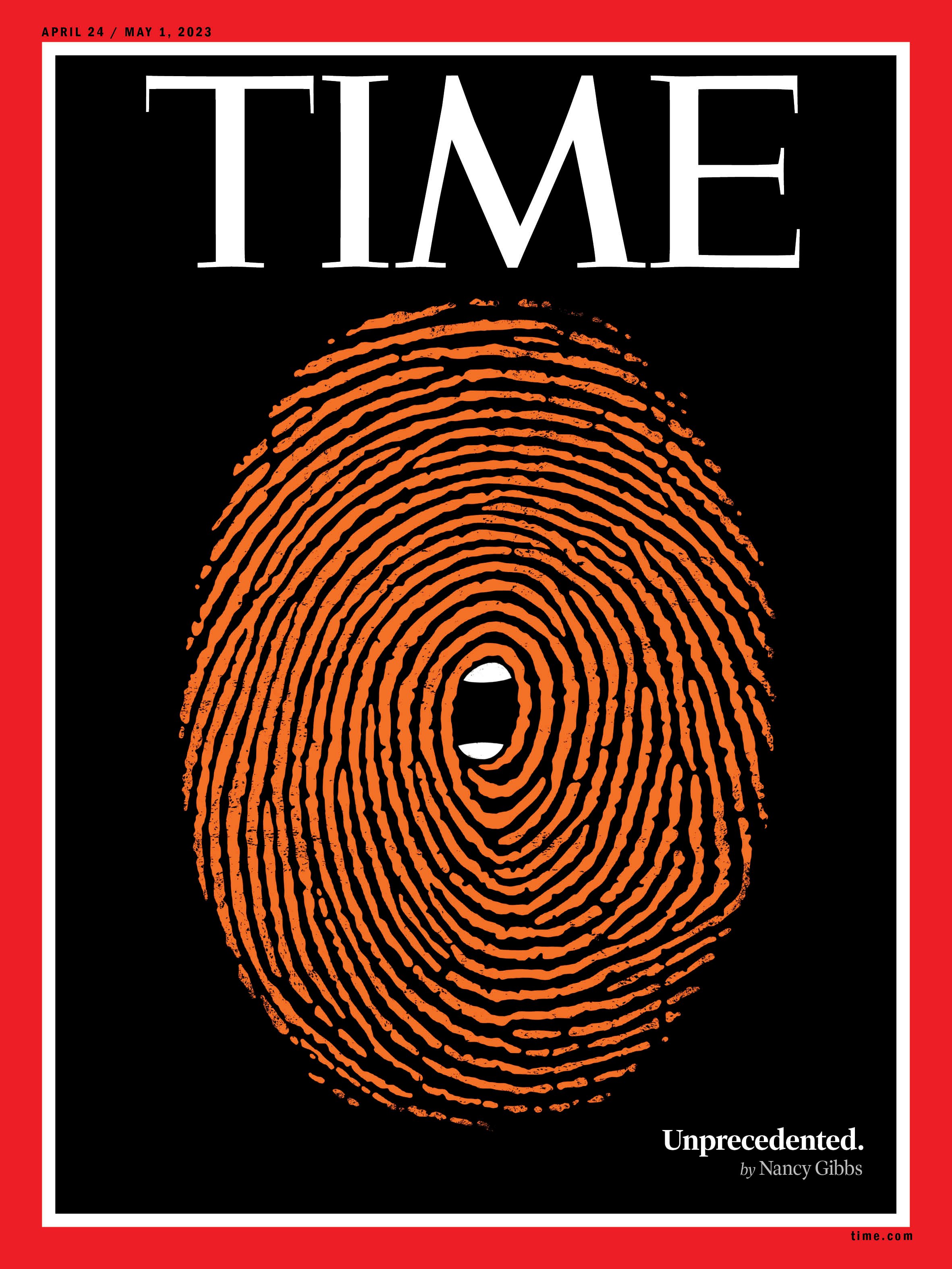

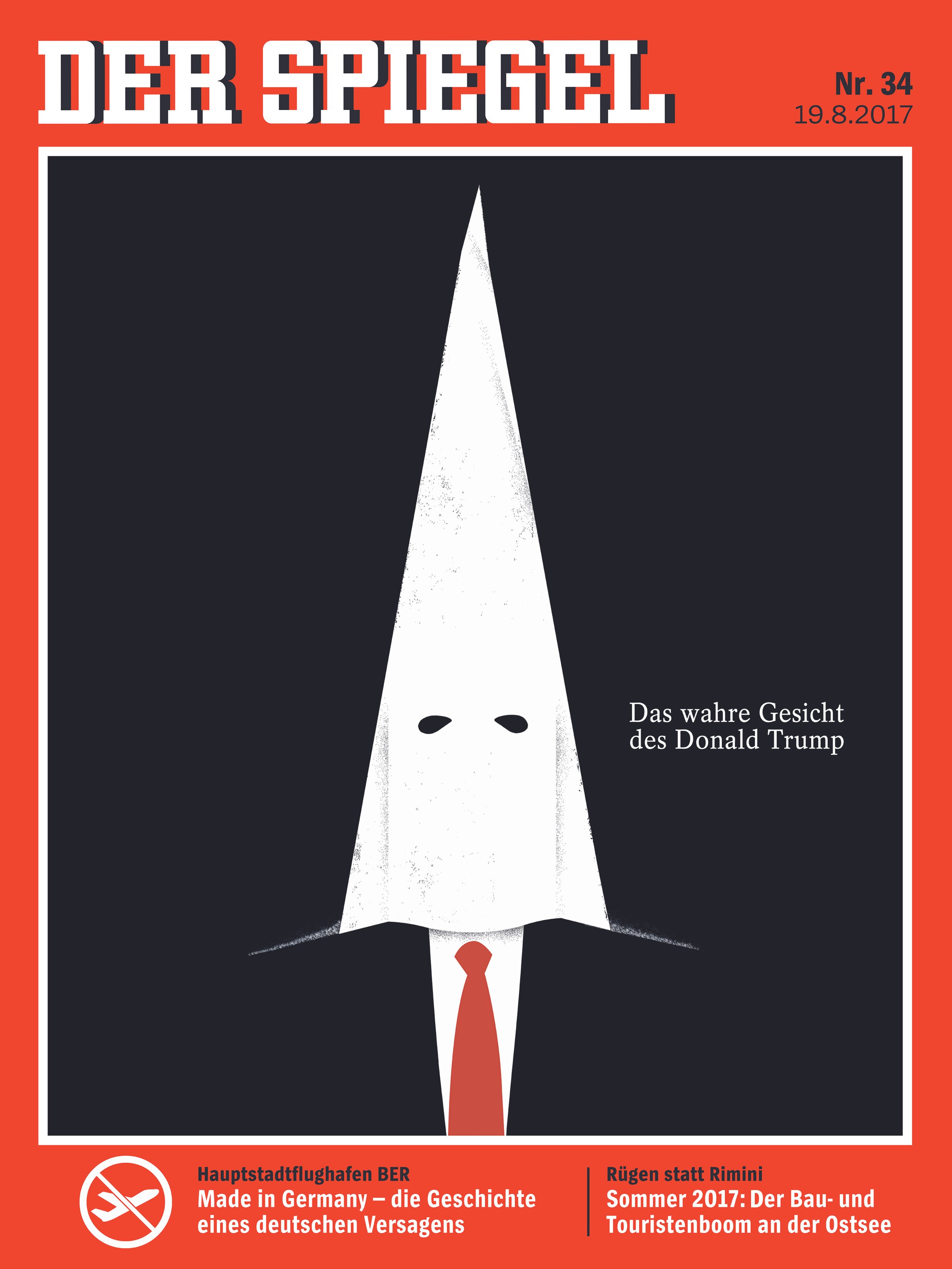

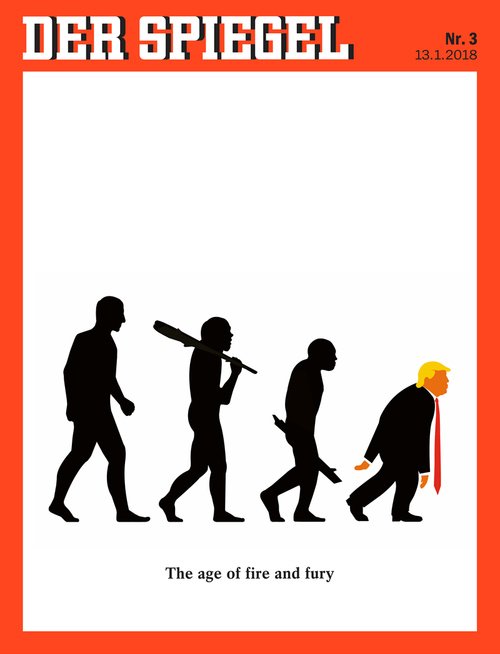

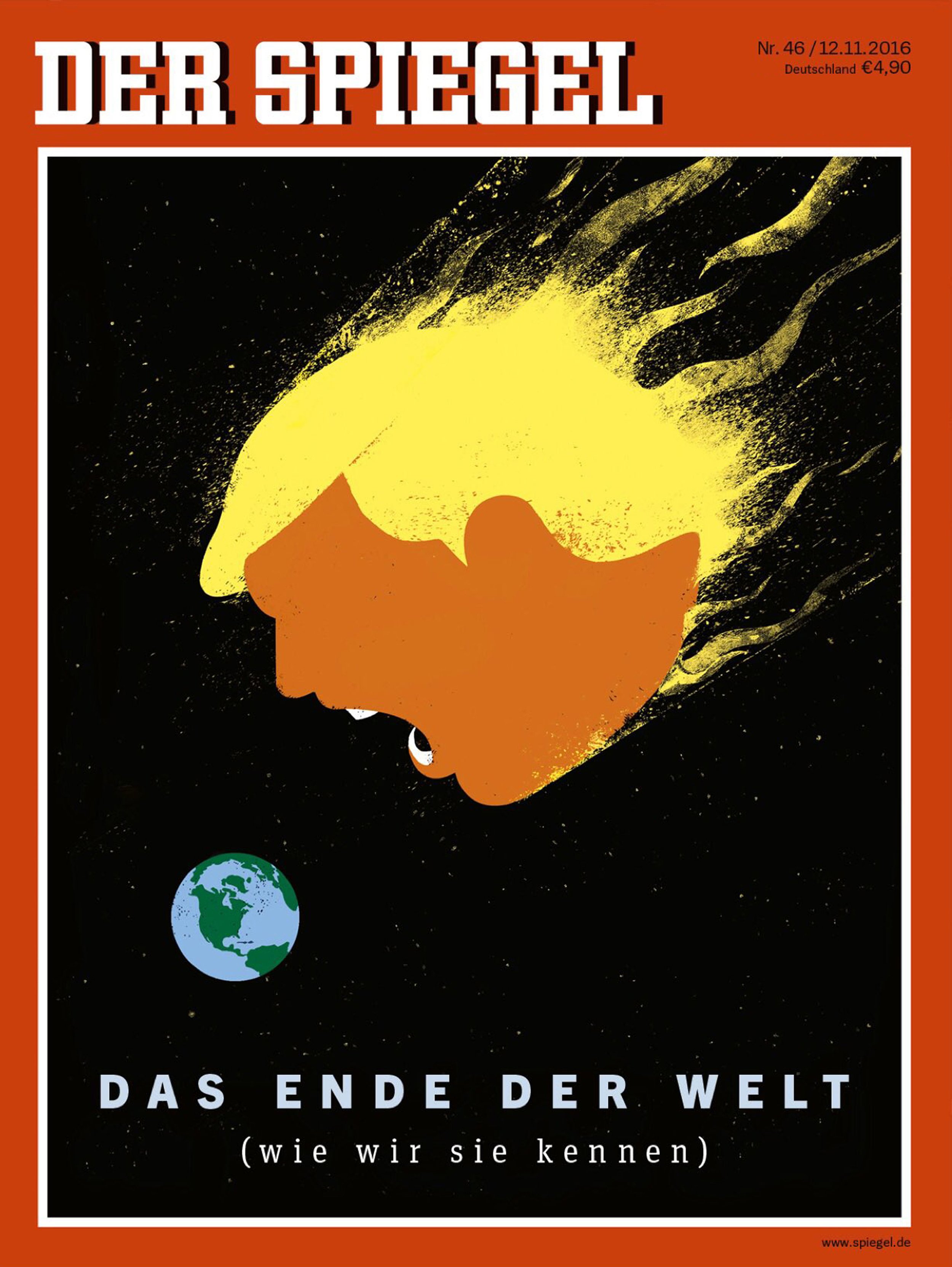

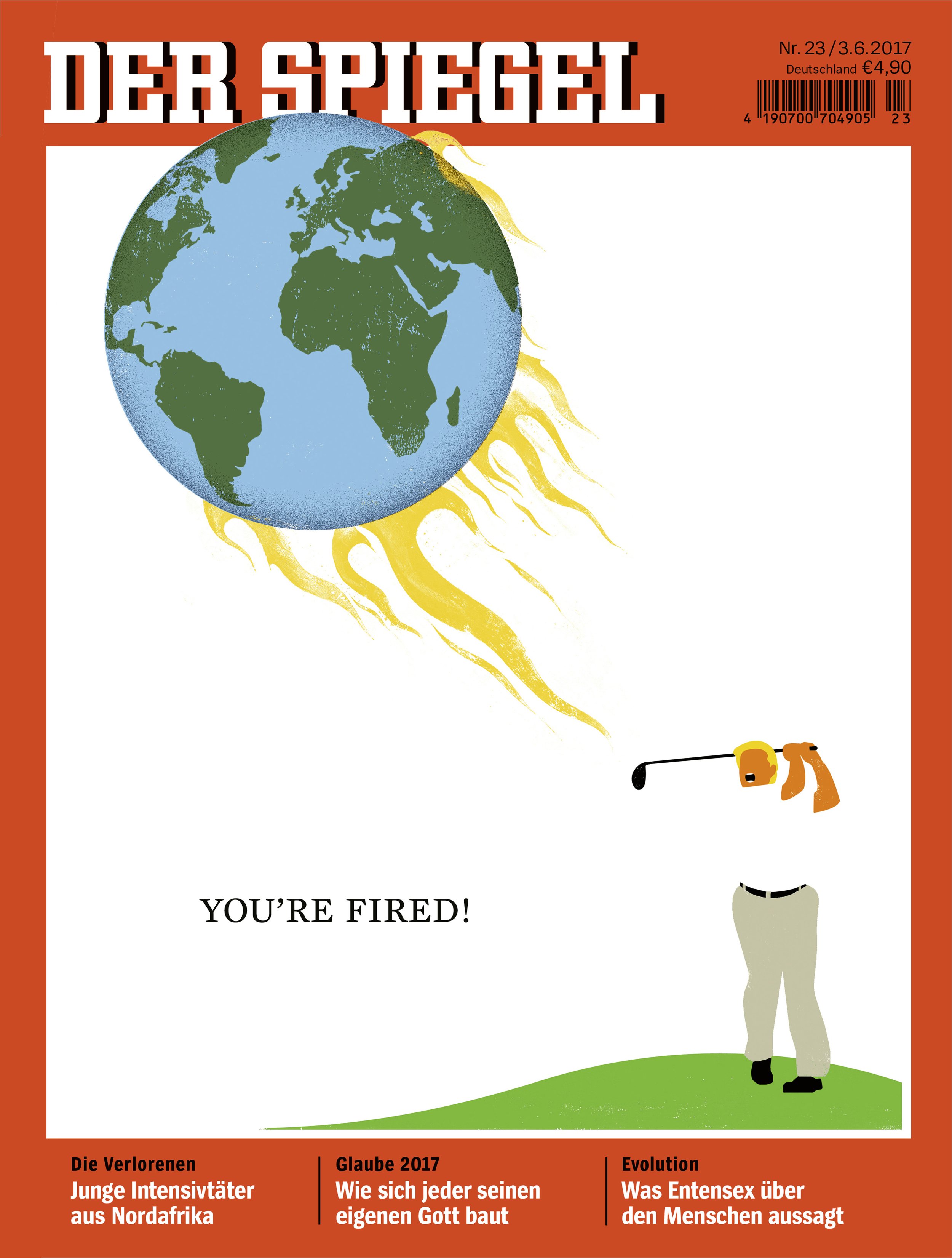

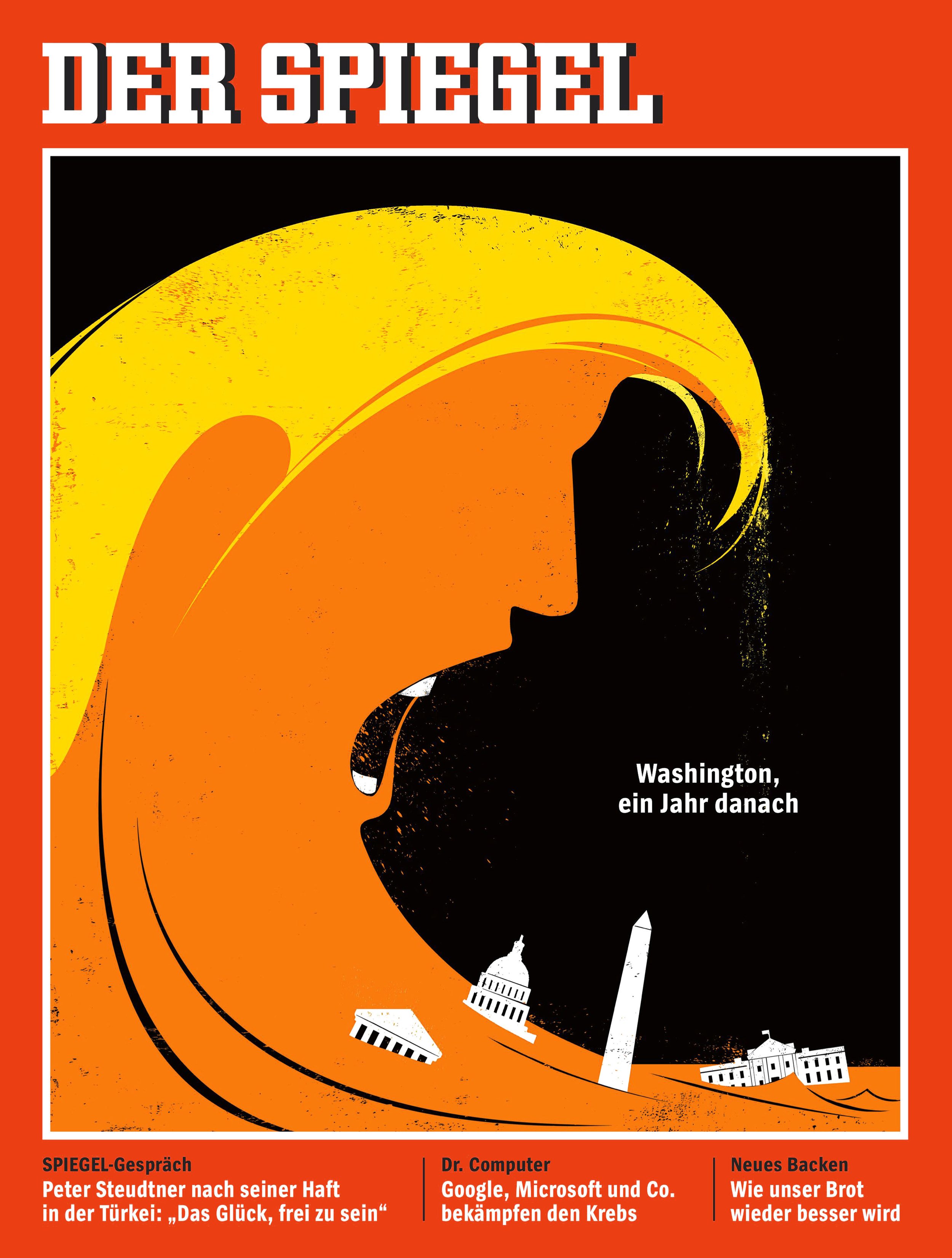

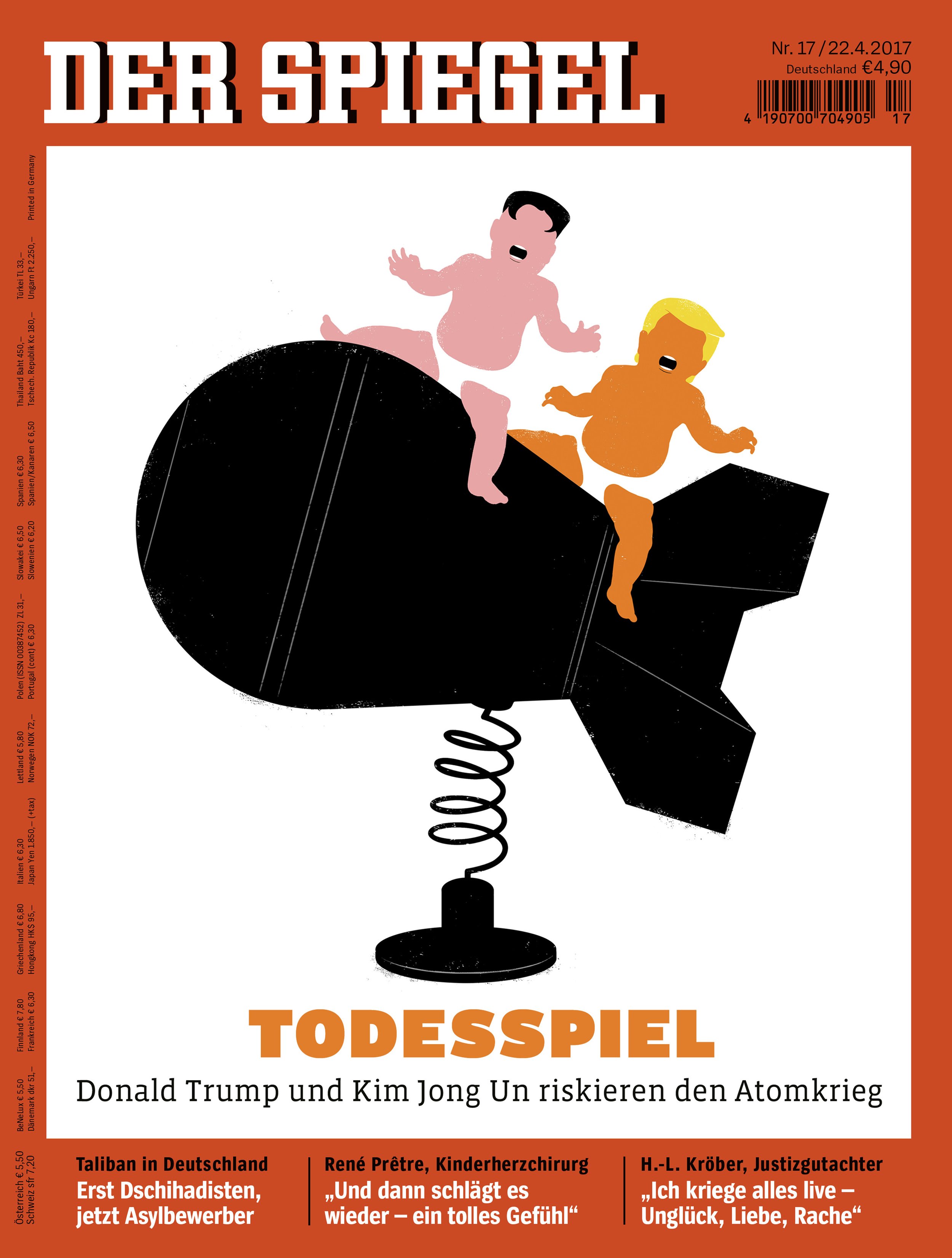

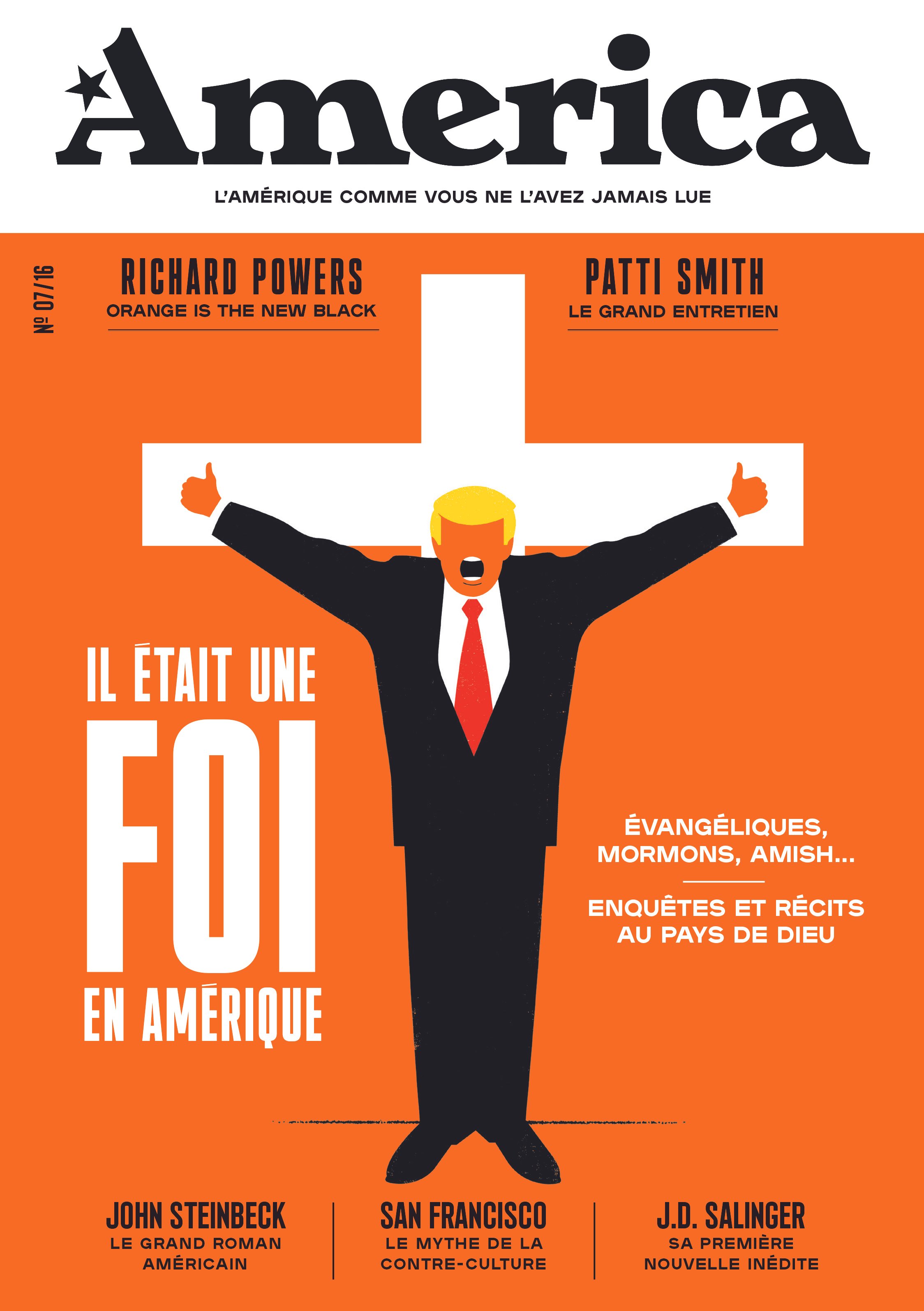

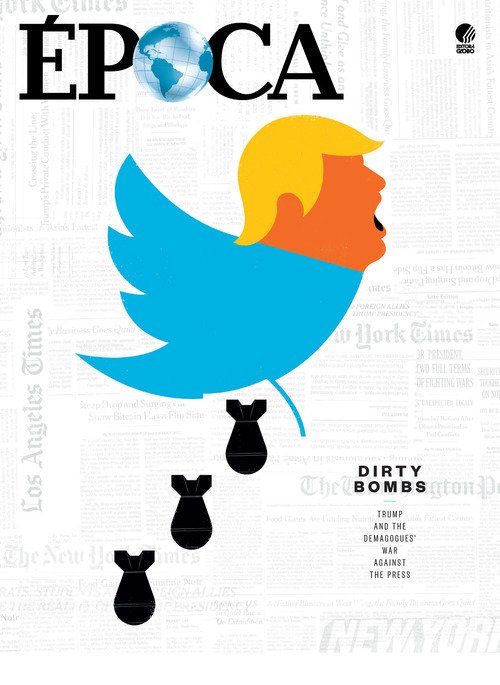

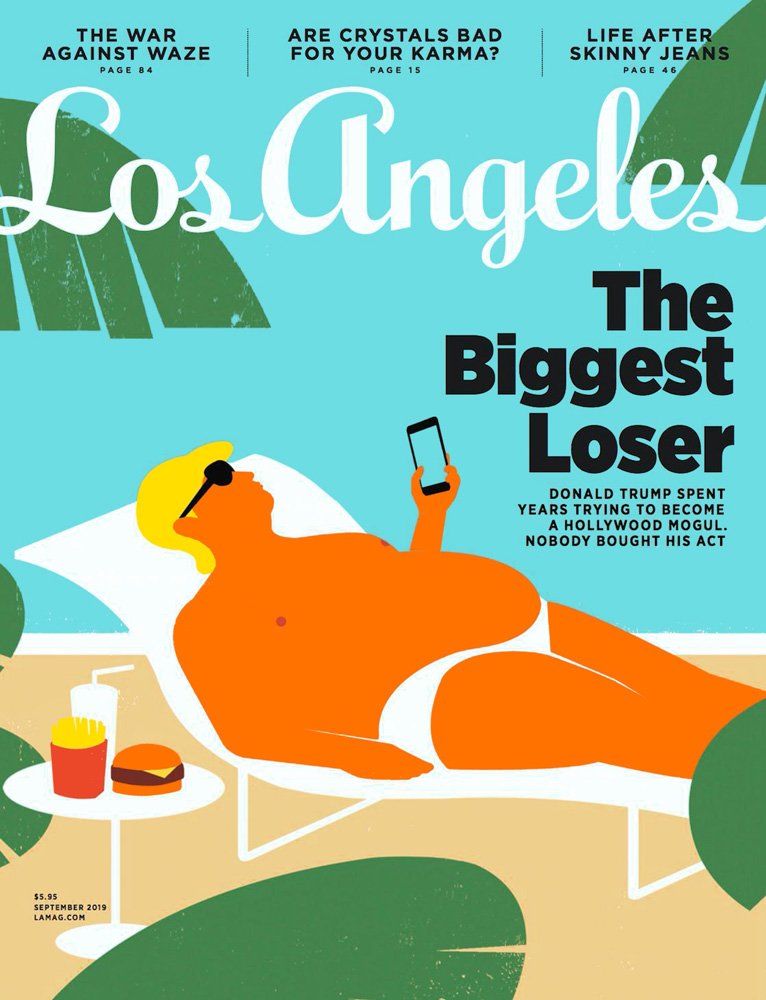

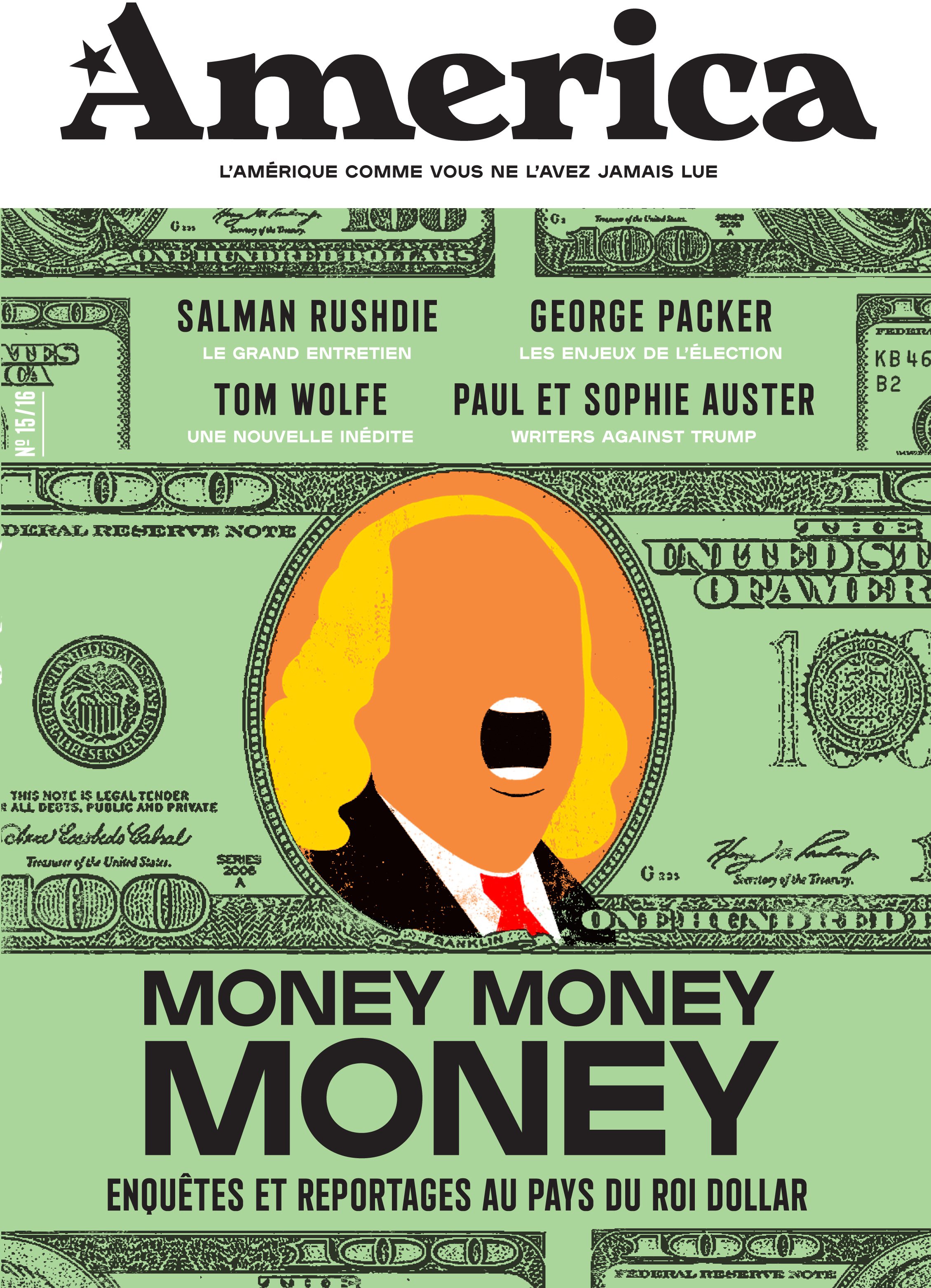

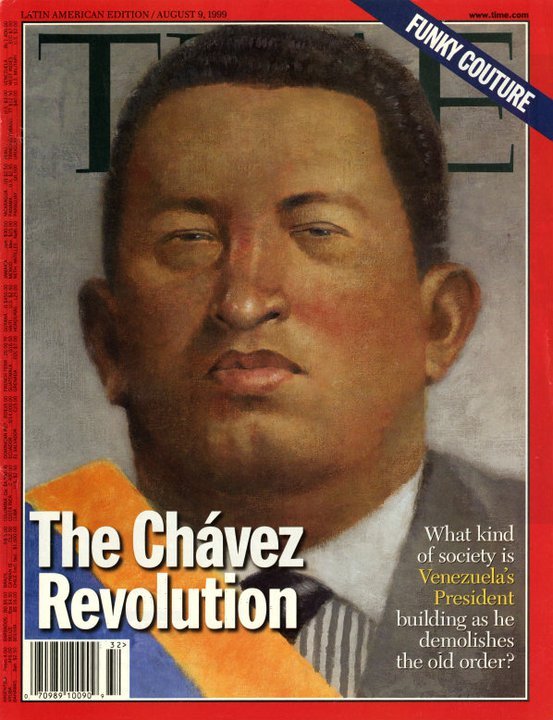

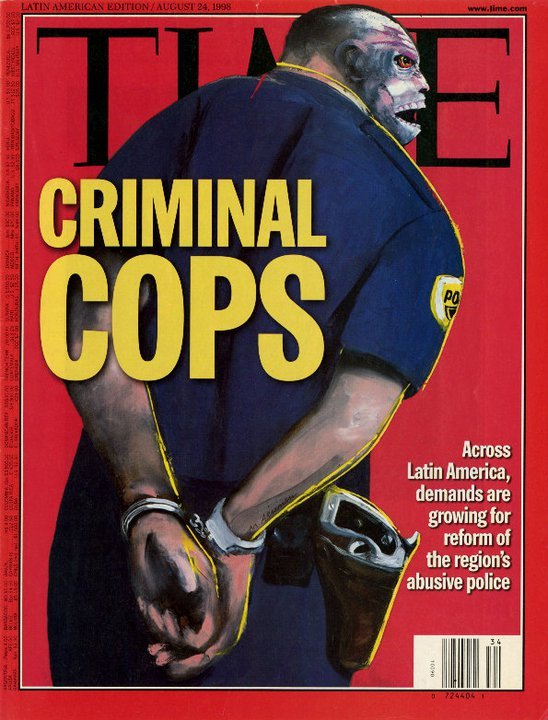

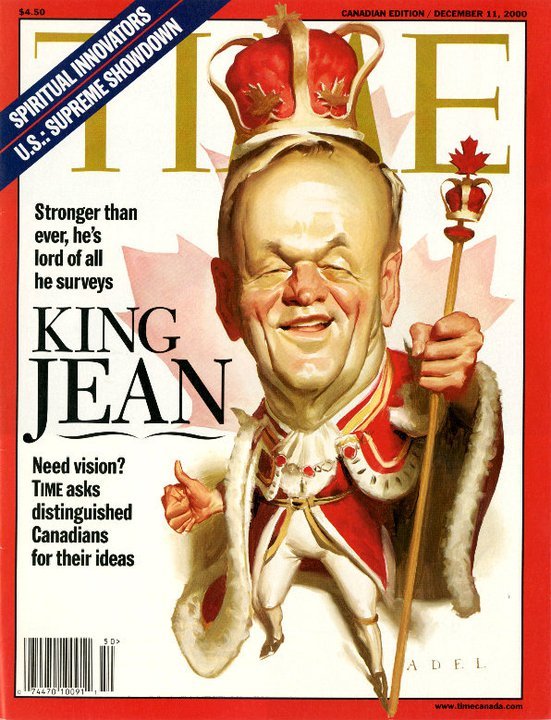

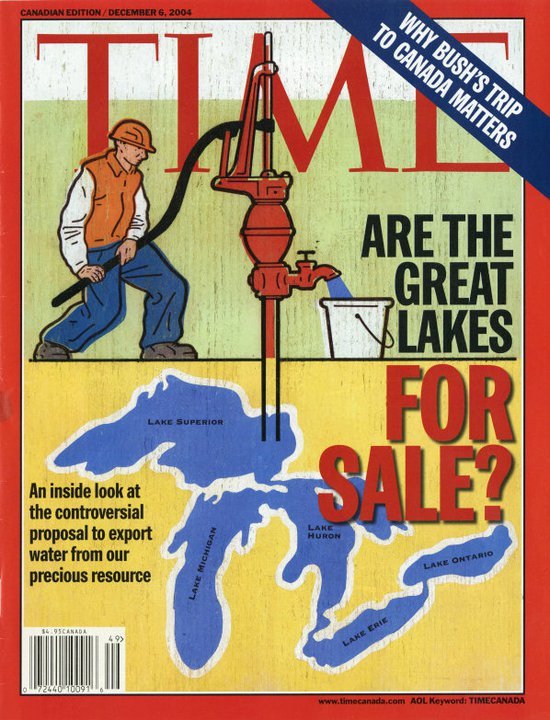

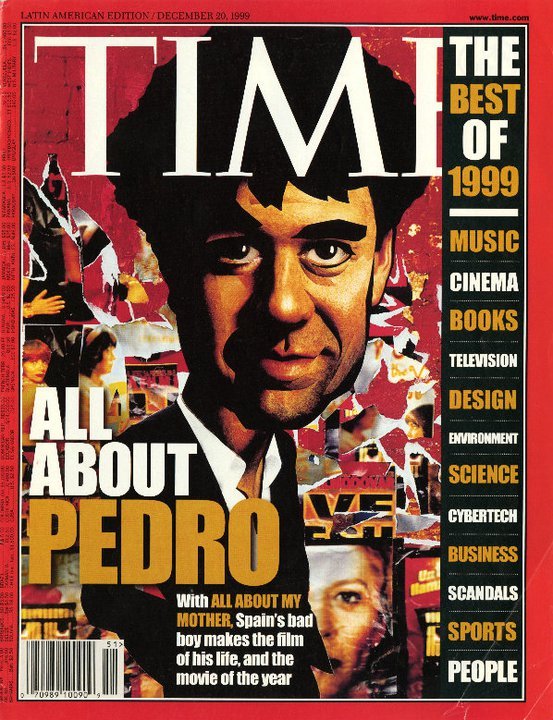

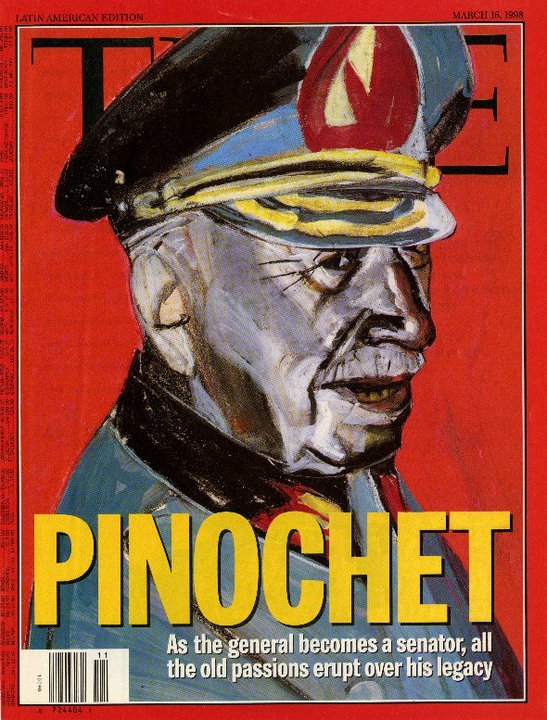

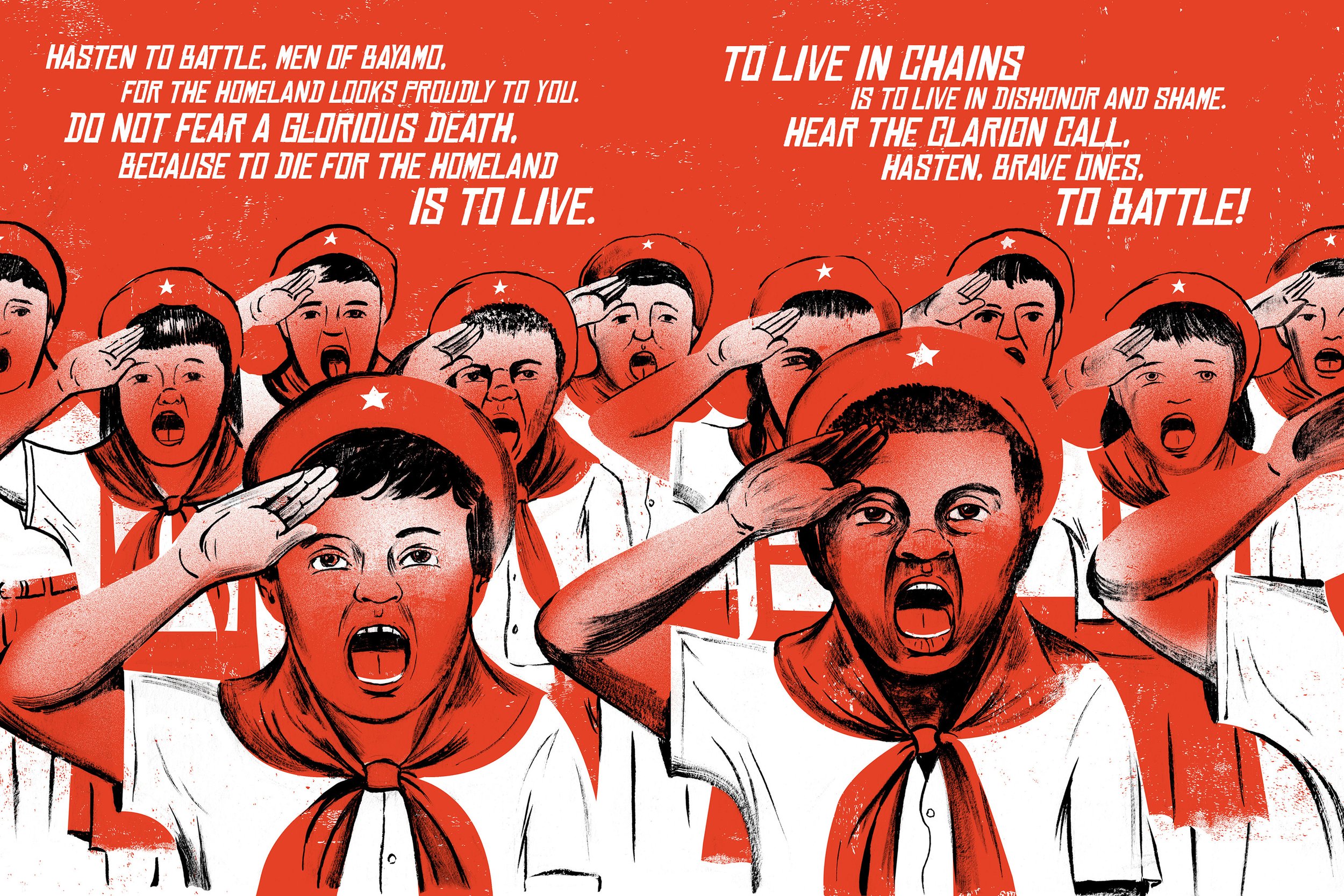

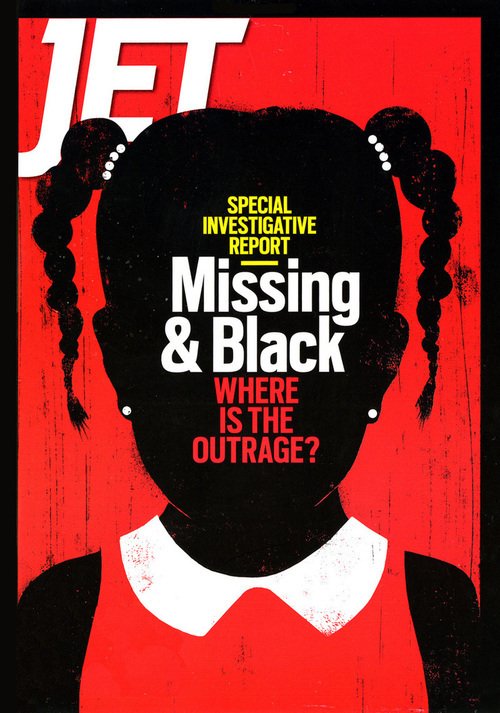

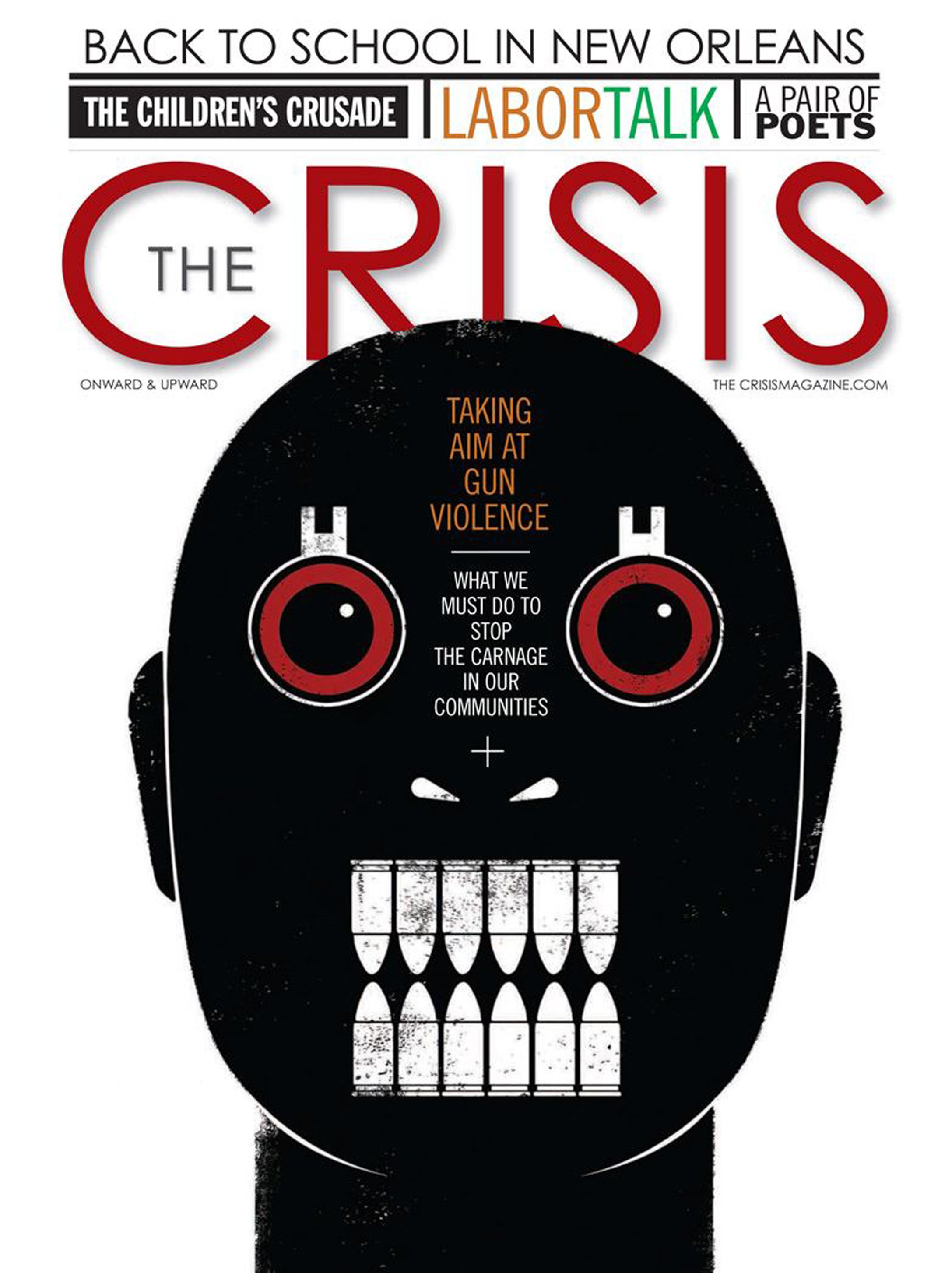

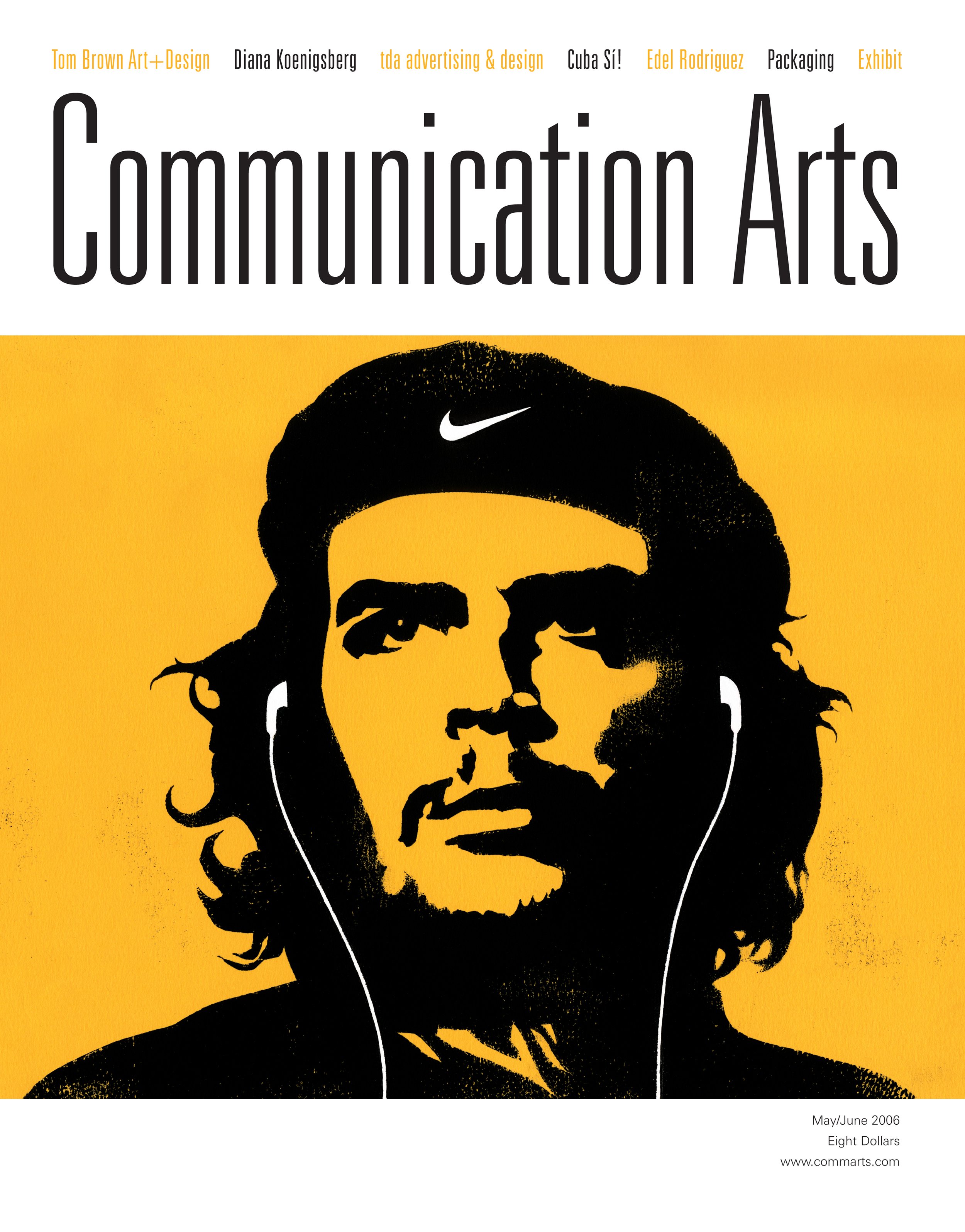

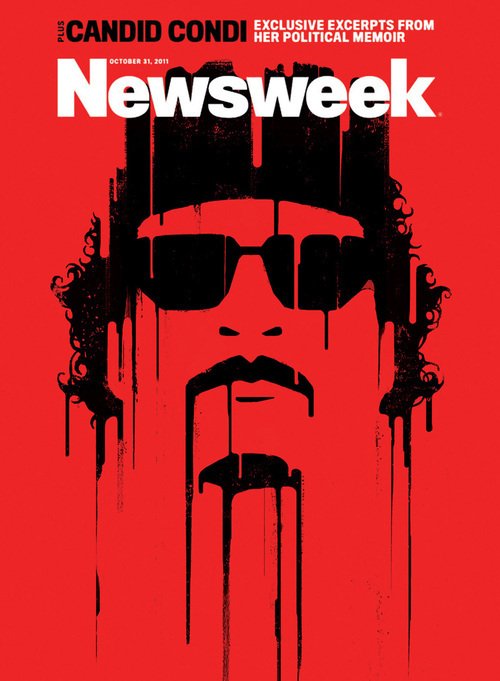

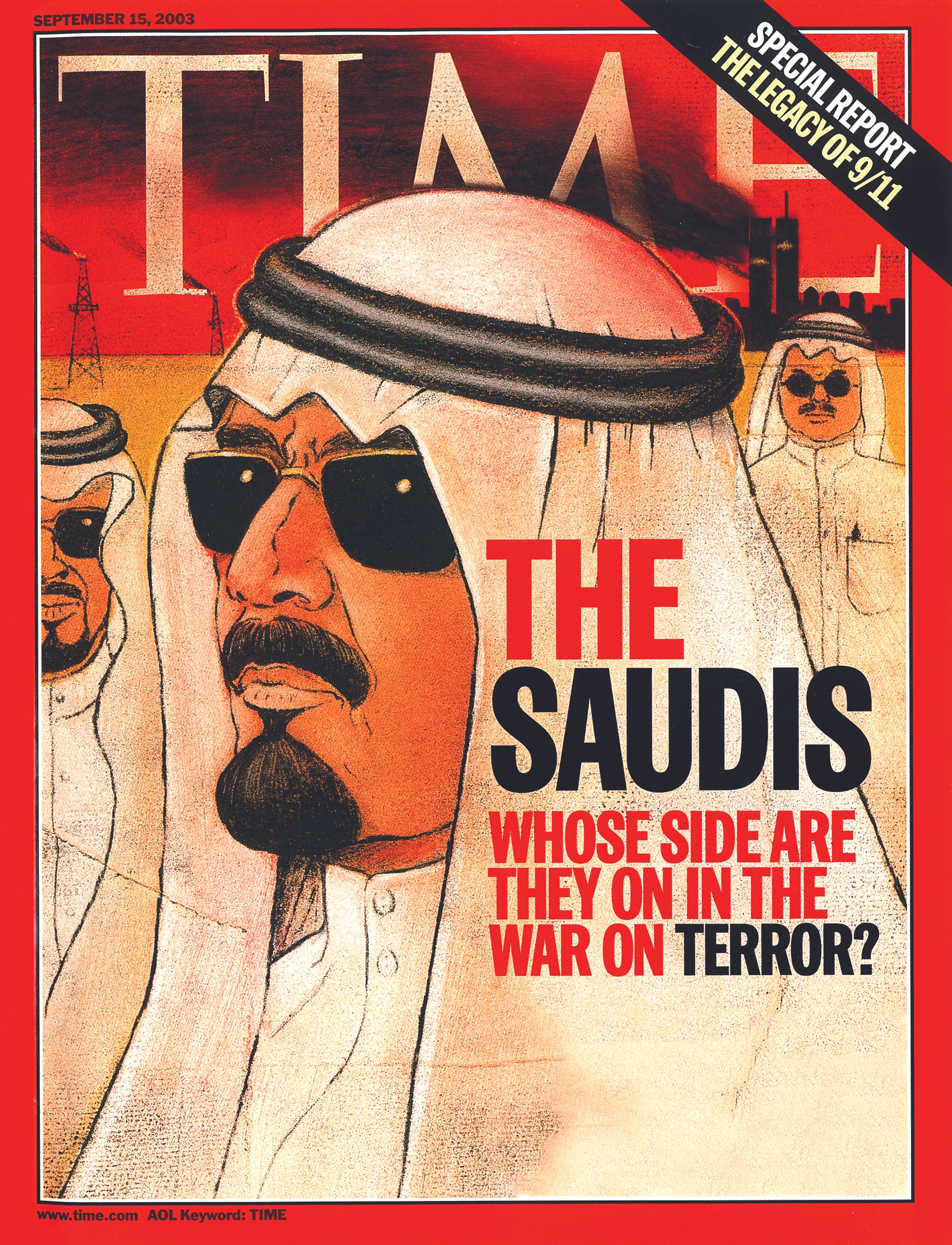

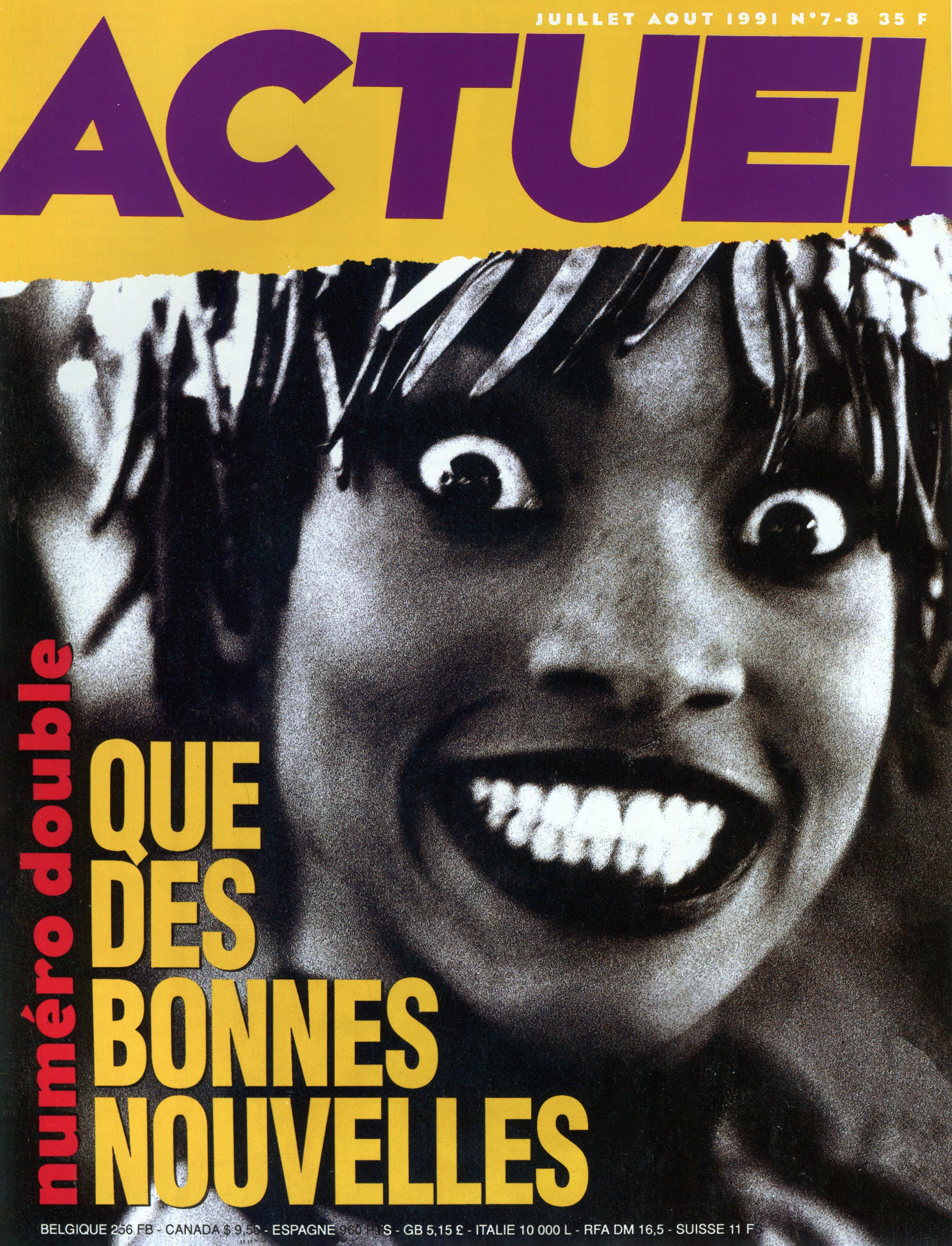

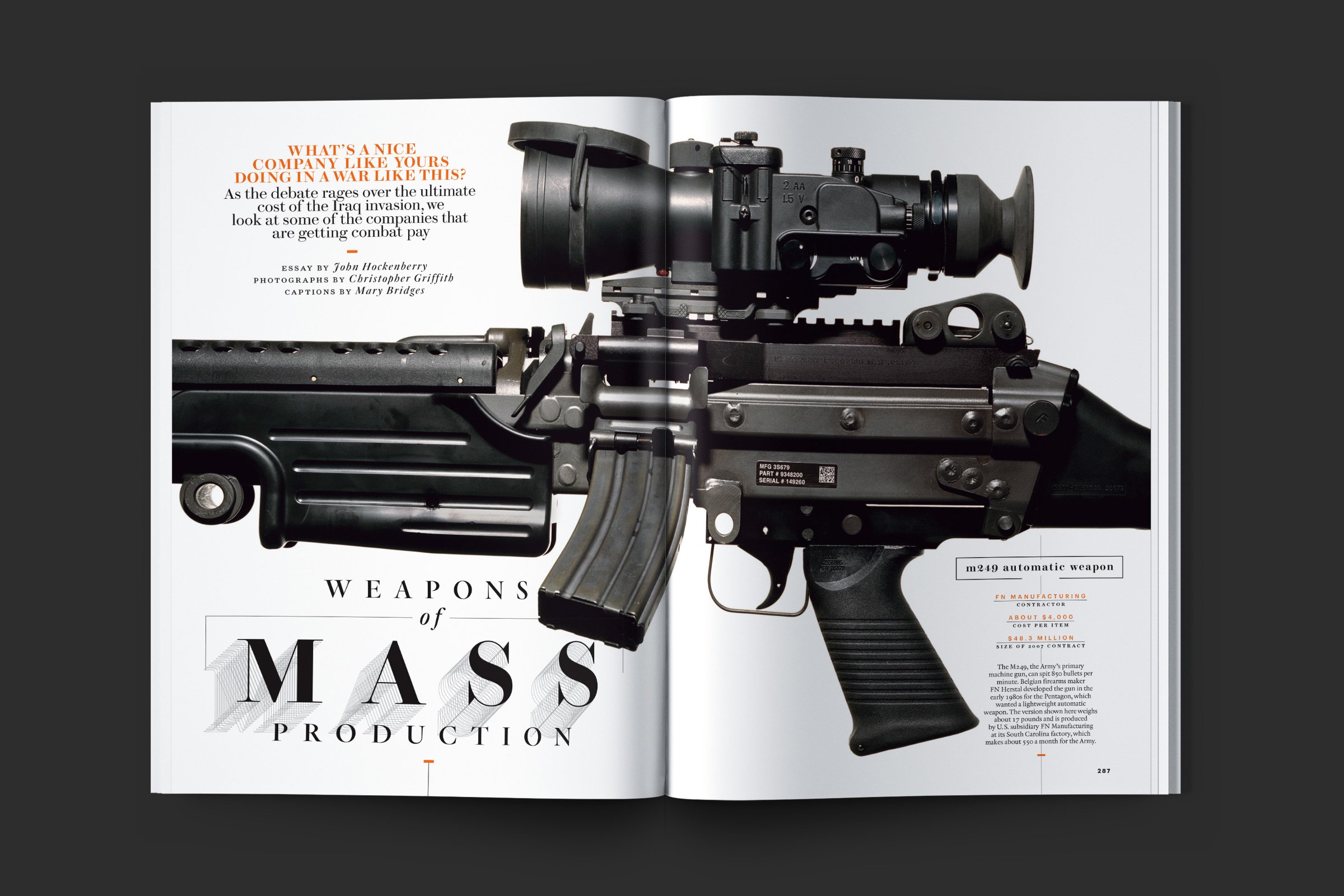

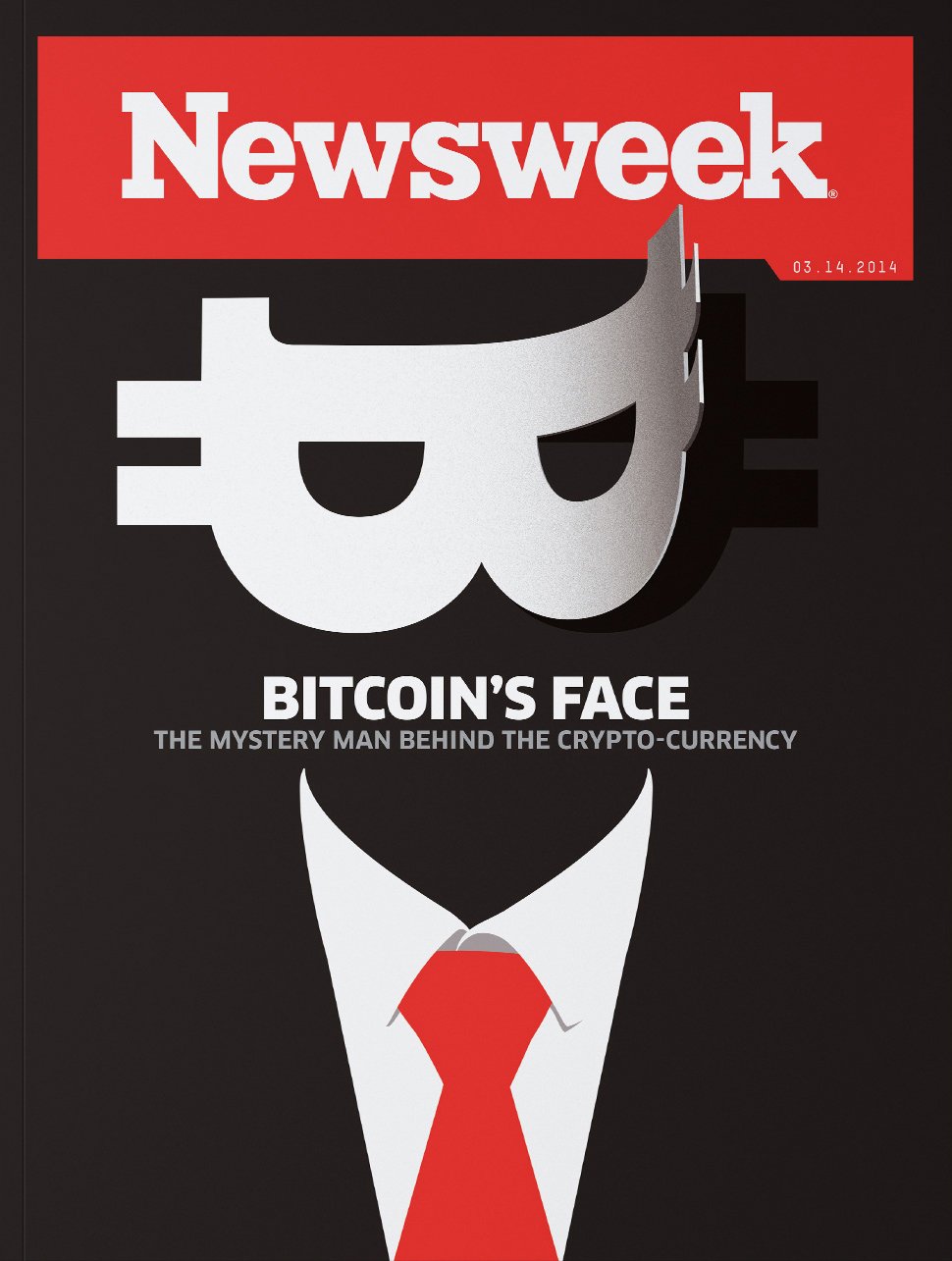

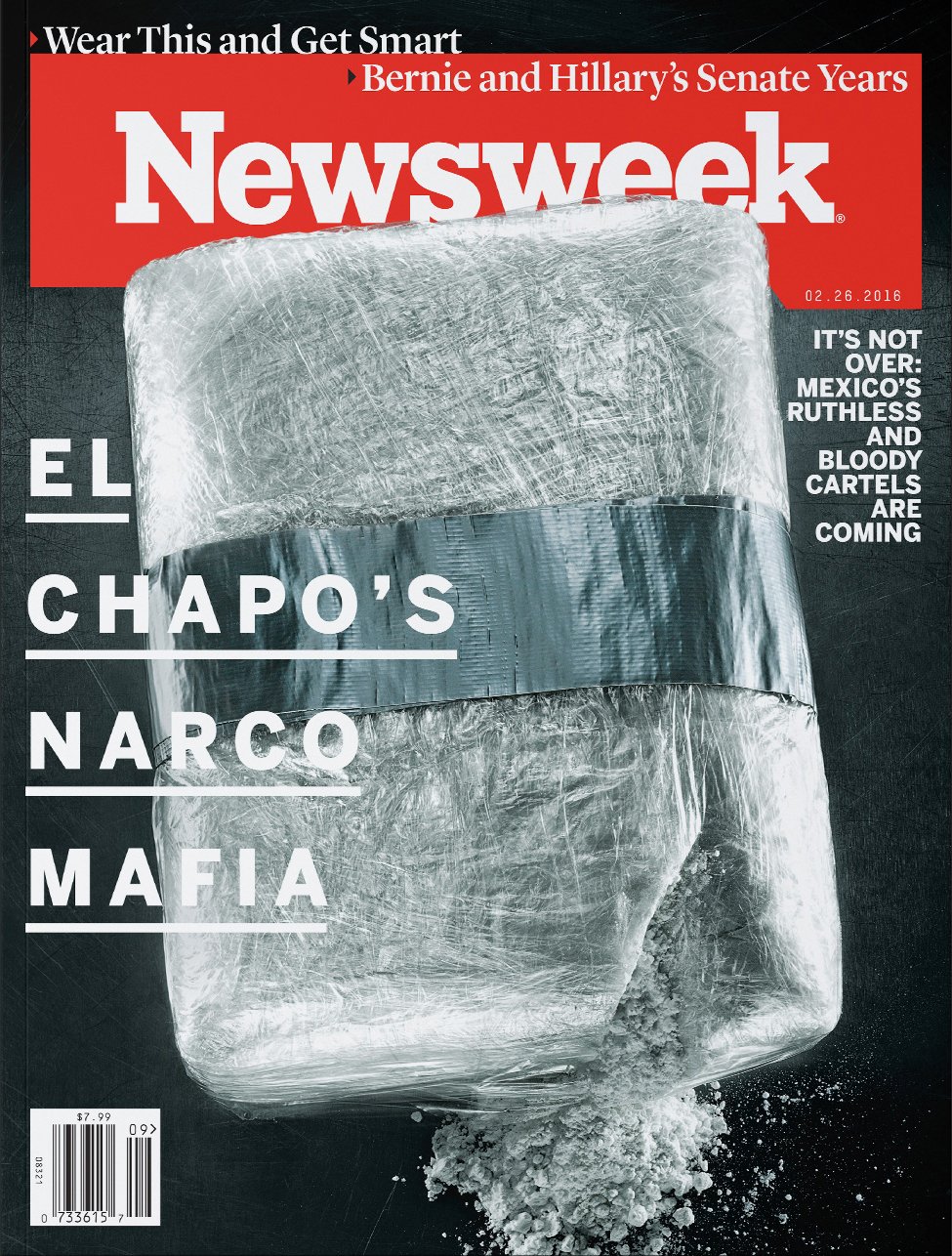

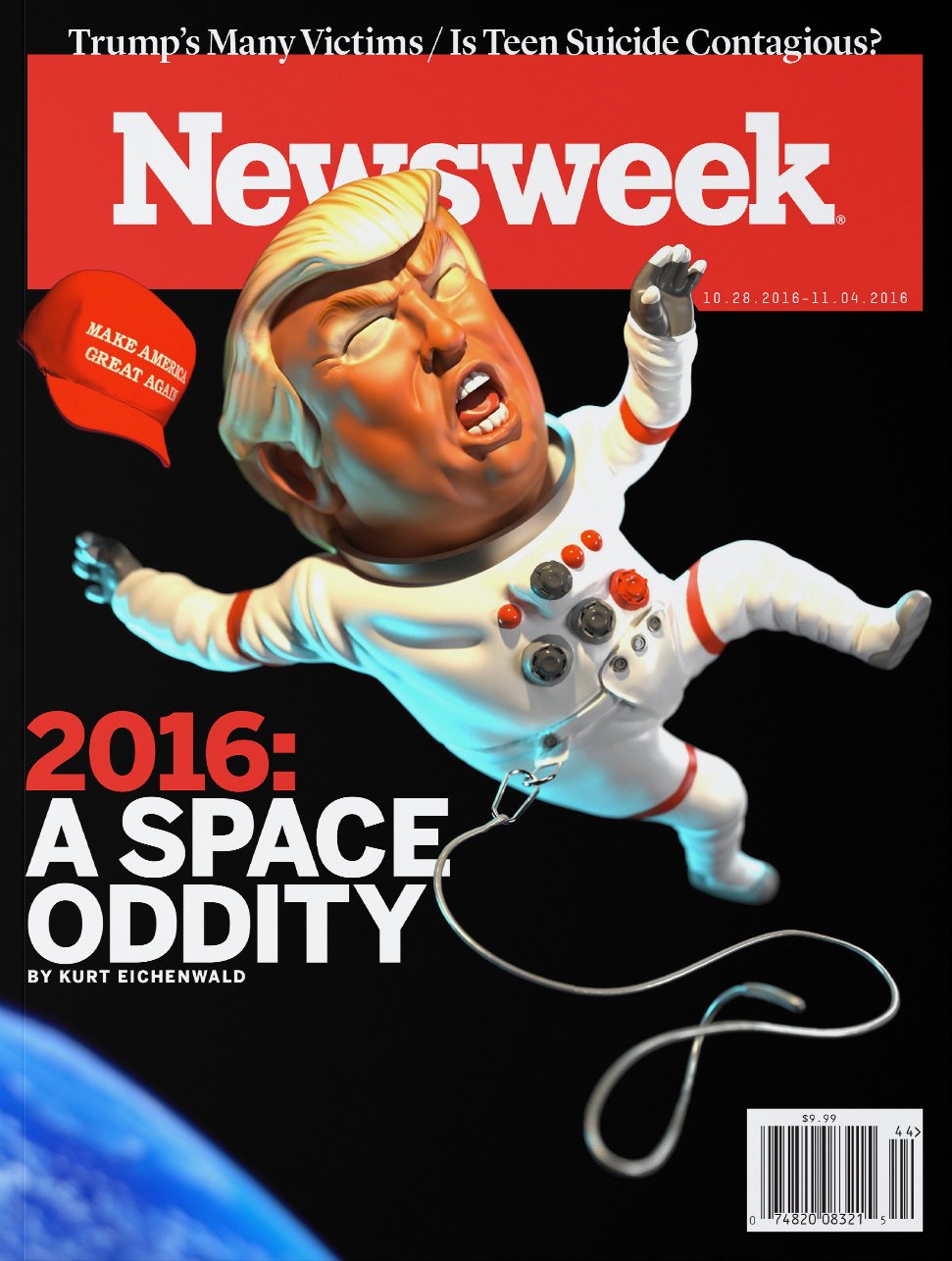

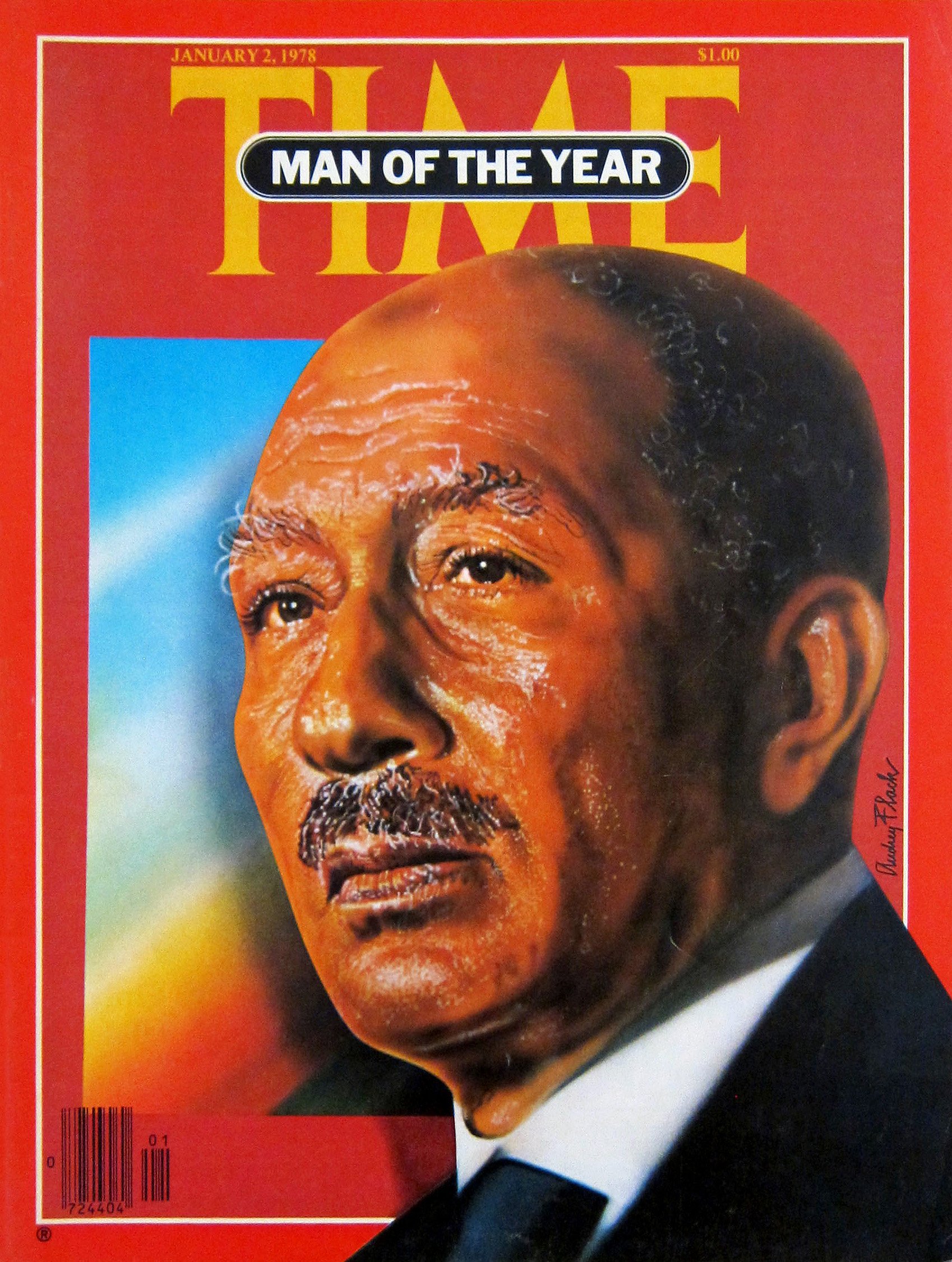

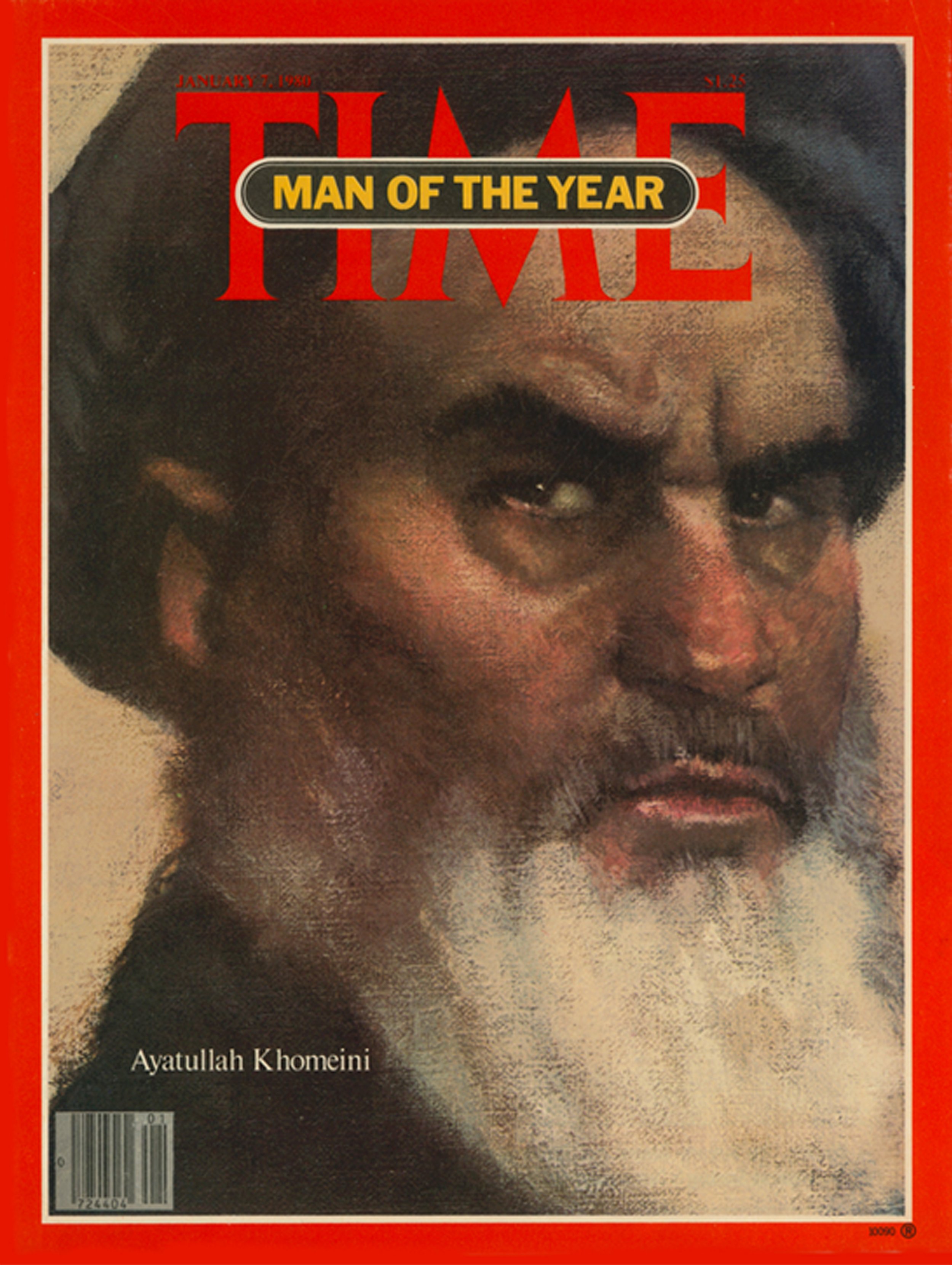

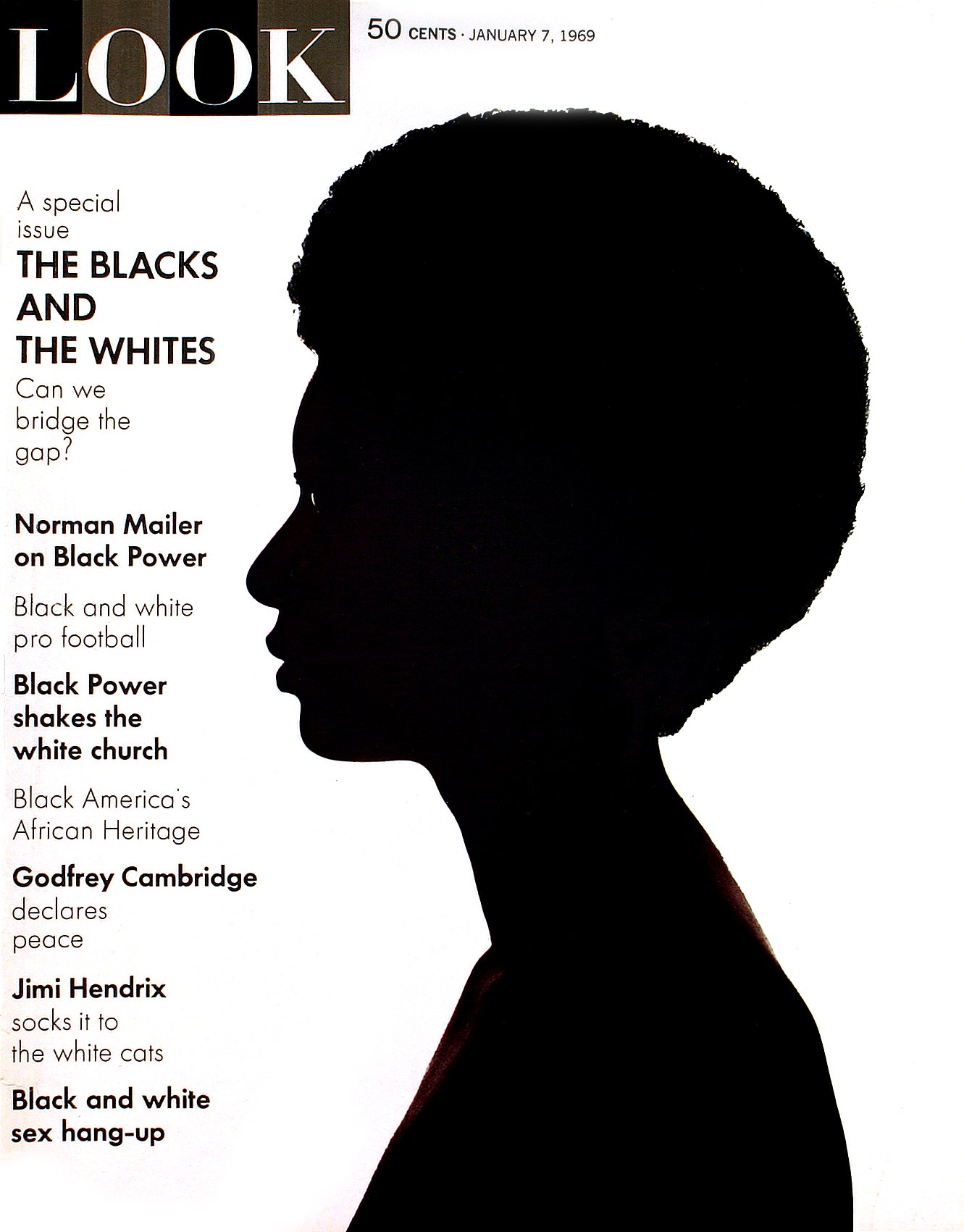

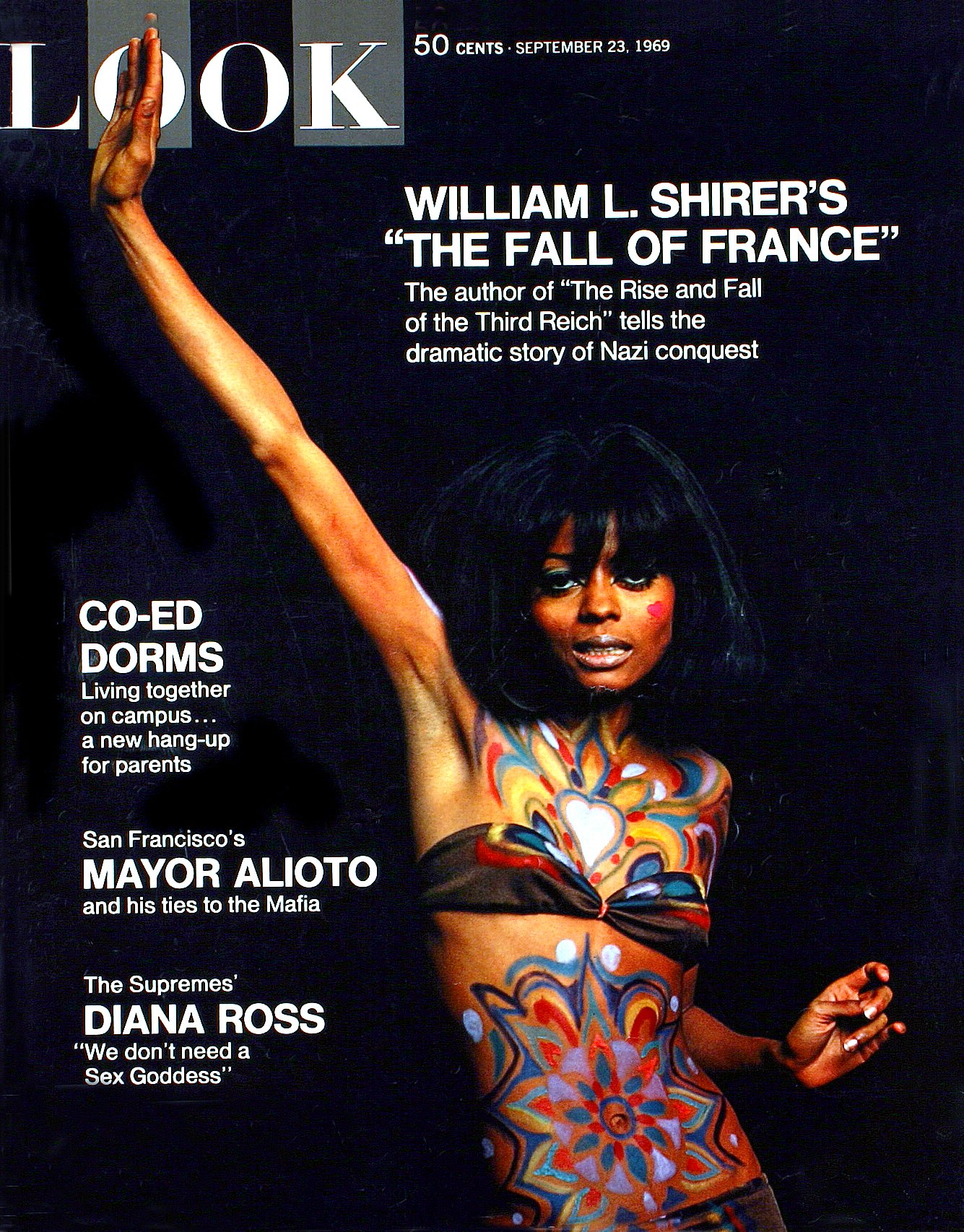

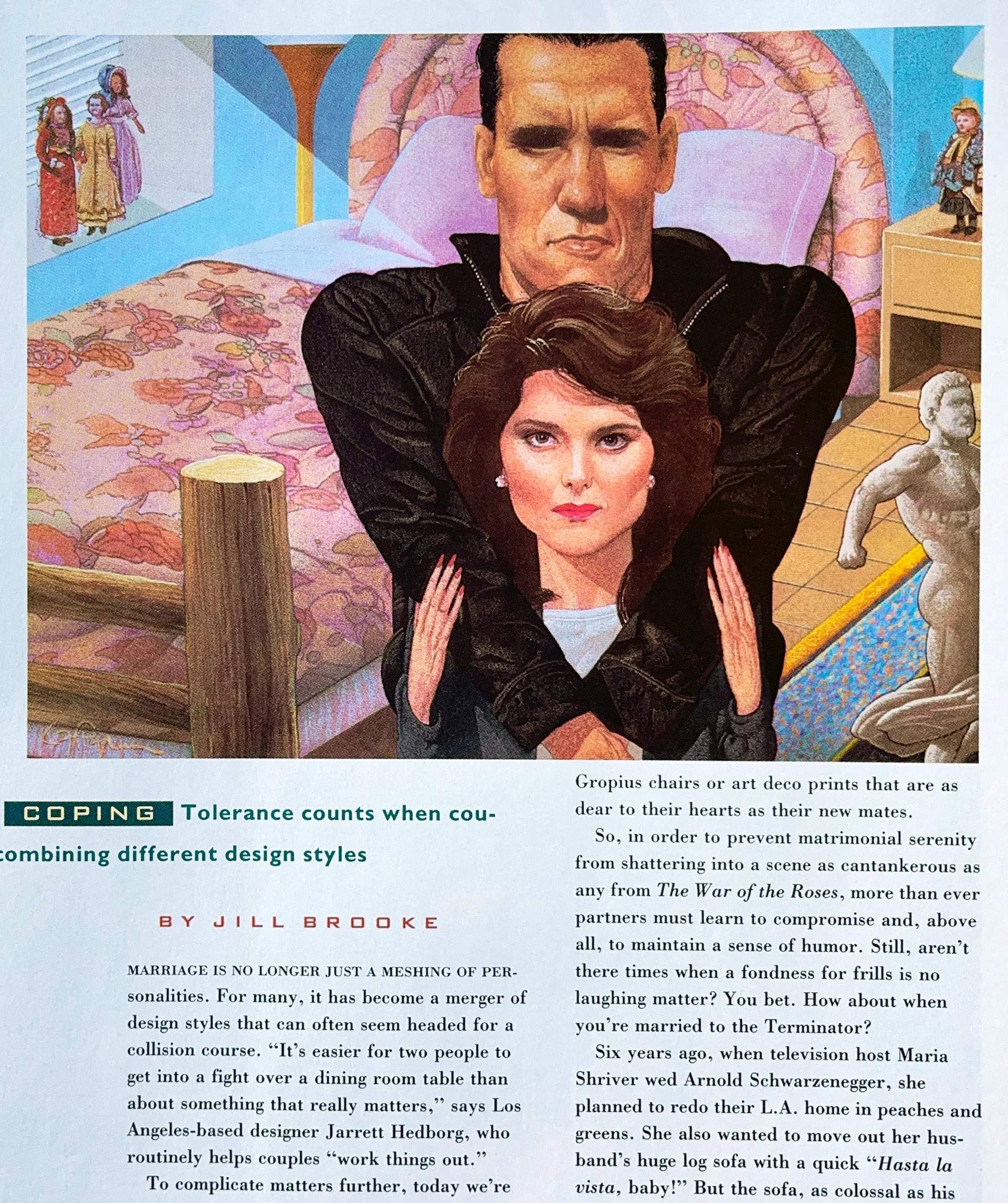

The images are iconic. And you know who they depict. They may be the most unforgettable magazine covers to emerge from the chaos of the late 2010s. Why are they so effective? Because of the implicit understanding of what’s being said between artist and audience—without a word being spoken. Using just three basic colors, today’s guest has created the brand identity of resistance.

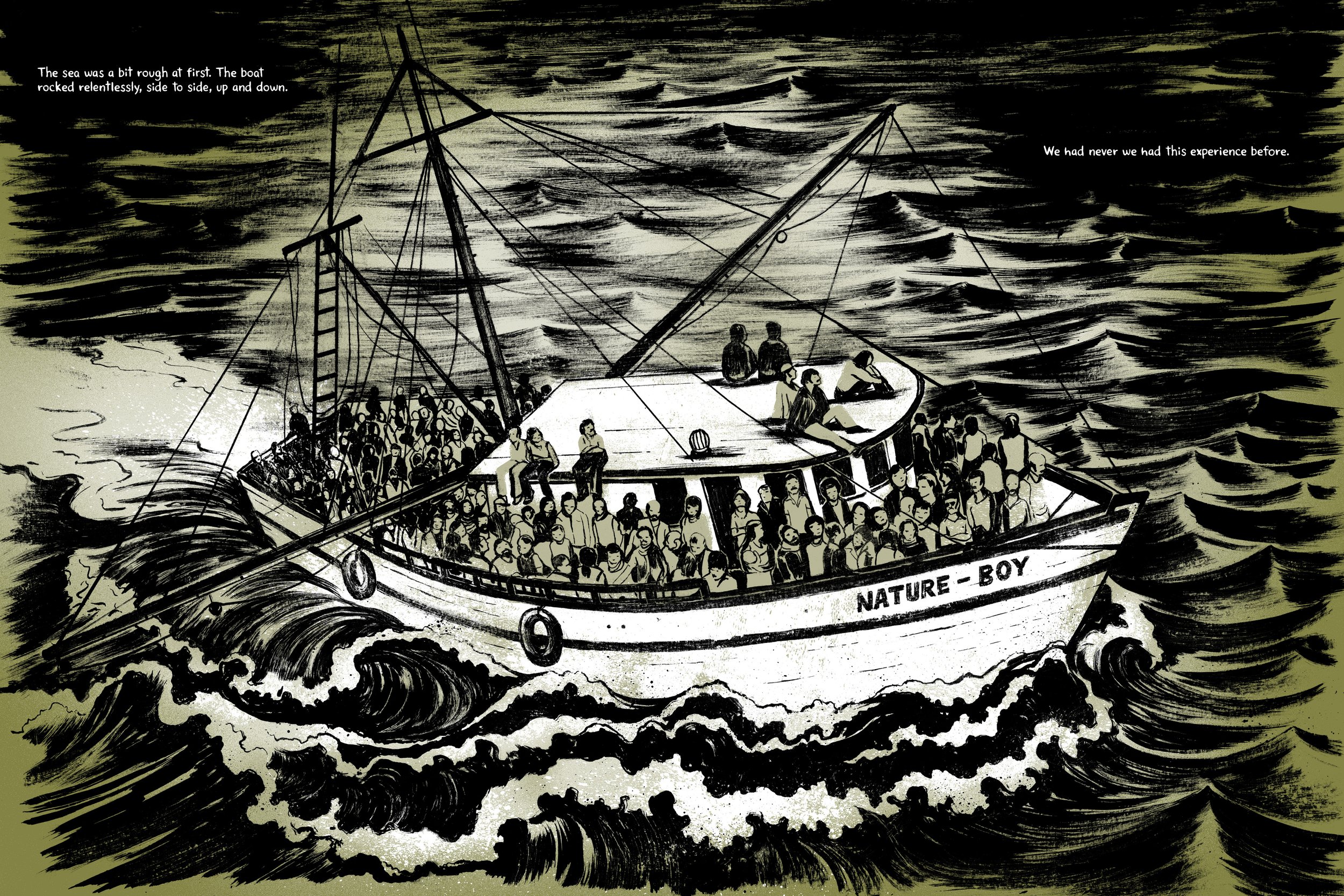

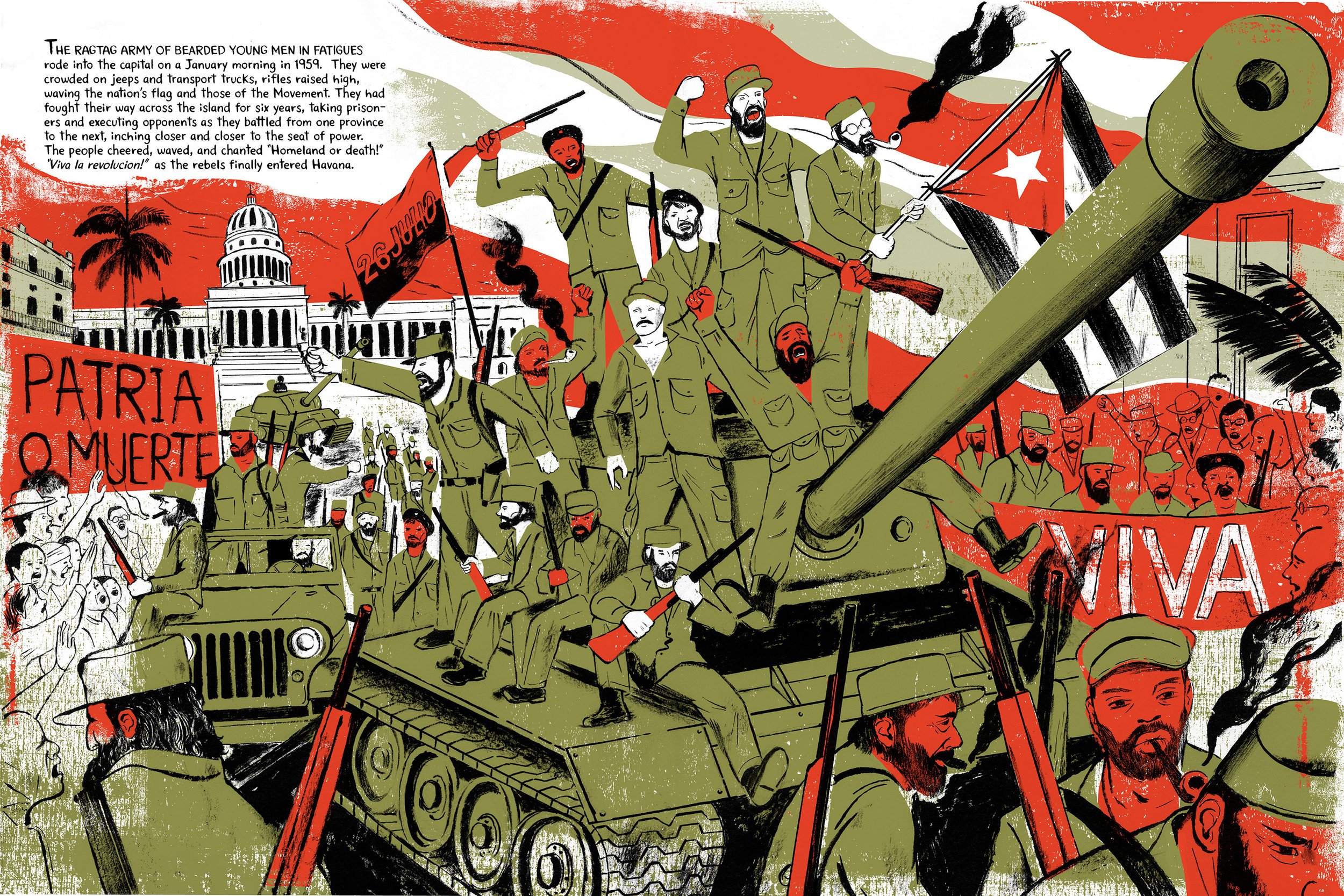

Edel Rodriguez was born in Cuba, and though he left that island nation when he was quite young, arriving in the US during the Mariel boatlift, one can’t help sensing an aesthetic that might be especially Cuban, or can be called, perhaps, “authoritarian-adjacent.” Because when the US flirted with—as it will again this year—a presidential candidate rotten with autocratic tendencies, Rodriguez’s imagery is the perfect match for the moment.

His red, yellow, and orange covers for Time, Mother Jones, and Der Spiegel—25 in all—were minimalist, dangerous, and dead-on-balls accurate. And he joins us today fresh off the premiere of his stunning graphic memoir, Worm: A Cuban American Odyssey.

Of his notorious subject, Rodriguez saw the famously orange skin tone as a “warning sign,” he told Fast Company, and the simple style he employed resonated because it broke through the noise in the most effective way imaginable. Coming from Cuba, Rodriguez feels a duty to express, through his art, the potential outcomes of the choices we have made—and might make yet again. As he told The Guardian, “I don’t think most Americans realize what a coup is.”

Of course, Rodriguez is more than just this one subject. But he’d be the first one to admit that he is political, and he makes no pretense of hiding his politics. As for his fans, they tell the artist that his work helps them crystallize their own thoughts and animates their feelings in ways they struggle to express on their own. A picture is worth a thousand words, indeed.

George Gendron: Now, if you’ve ever heard our podcasts we usually don’t talk politics here, but I’ve got to ask you, given your reputation, who did you vote for in the last election?

Edel Rodriguez: The last American election? Yeah. I pretty much voted for the entire Democrat party for a long time. Yeah, if that’s not clear enough. There’s basically one party that’s gone insane and another party that is just trying to manage the place. And so I just vote for that party.